Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea

Zeno of Elea was a Greek philosopher who lived in the 5th Century BCE. He described a set of paradoxes to prove that space and time are continuous and cannot be divided into discrete parts. The most famous of these are the Paradox of Achilles and the Tortoise, which purportedly shows that Achilles could never catch up with the much slower Tortoise, and the Paradox of the Arrow, which shows that an arrow in flight is always stationary.

Life of Zeno

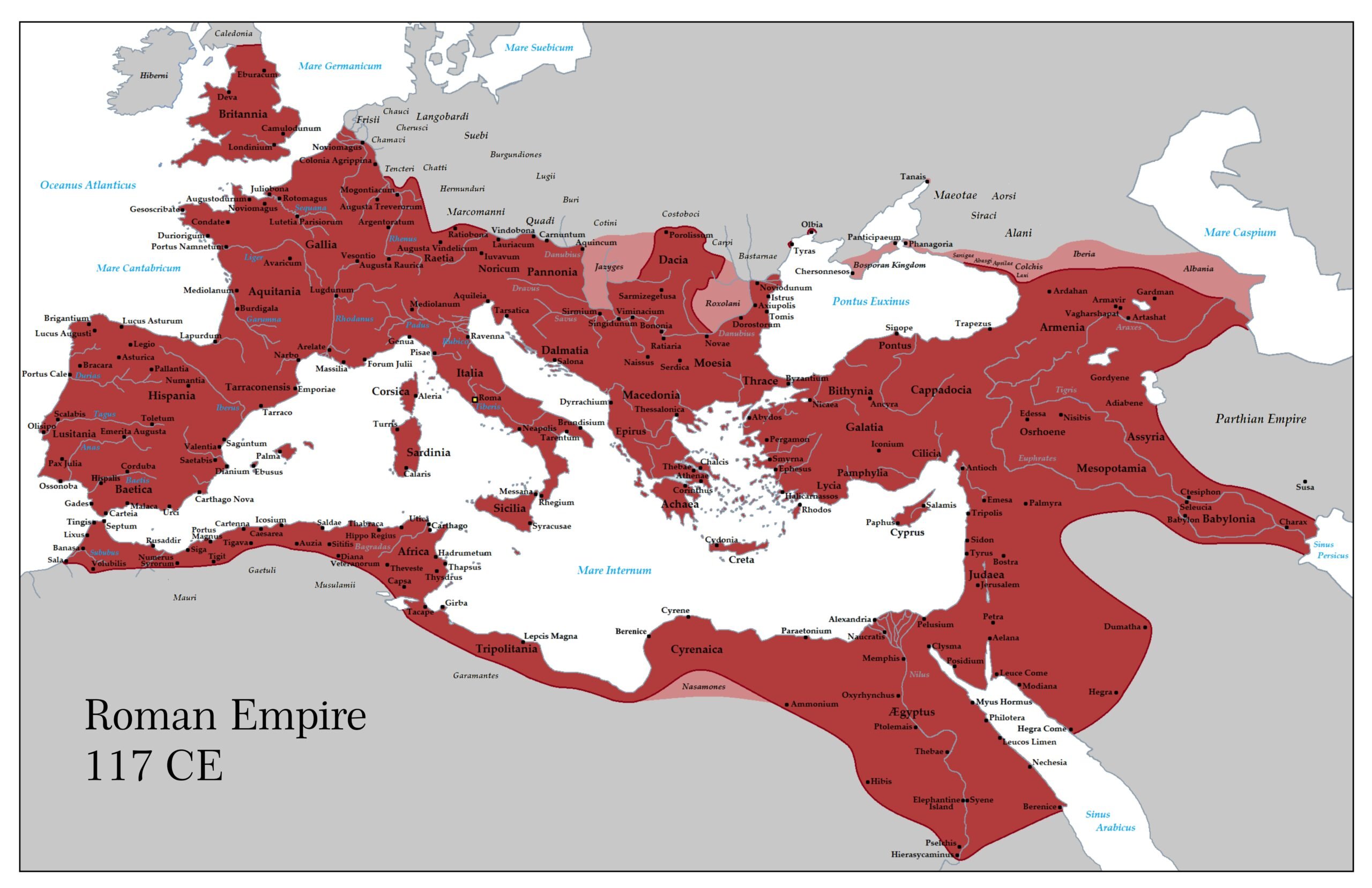

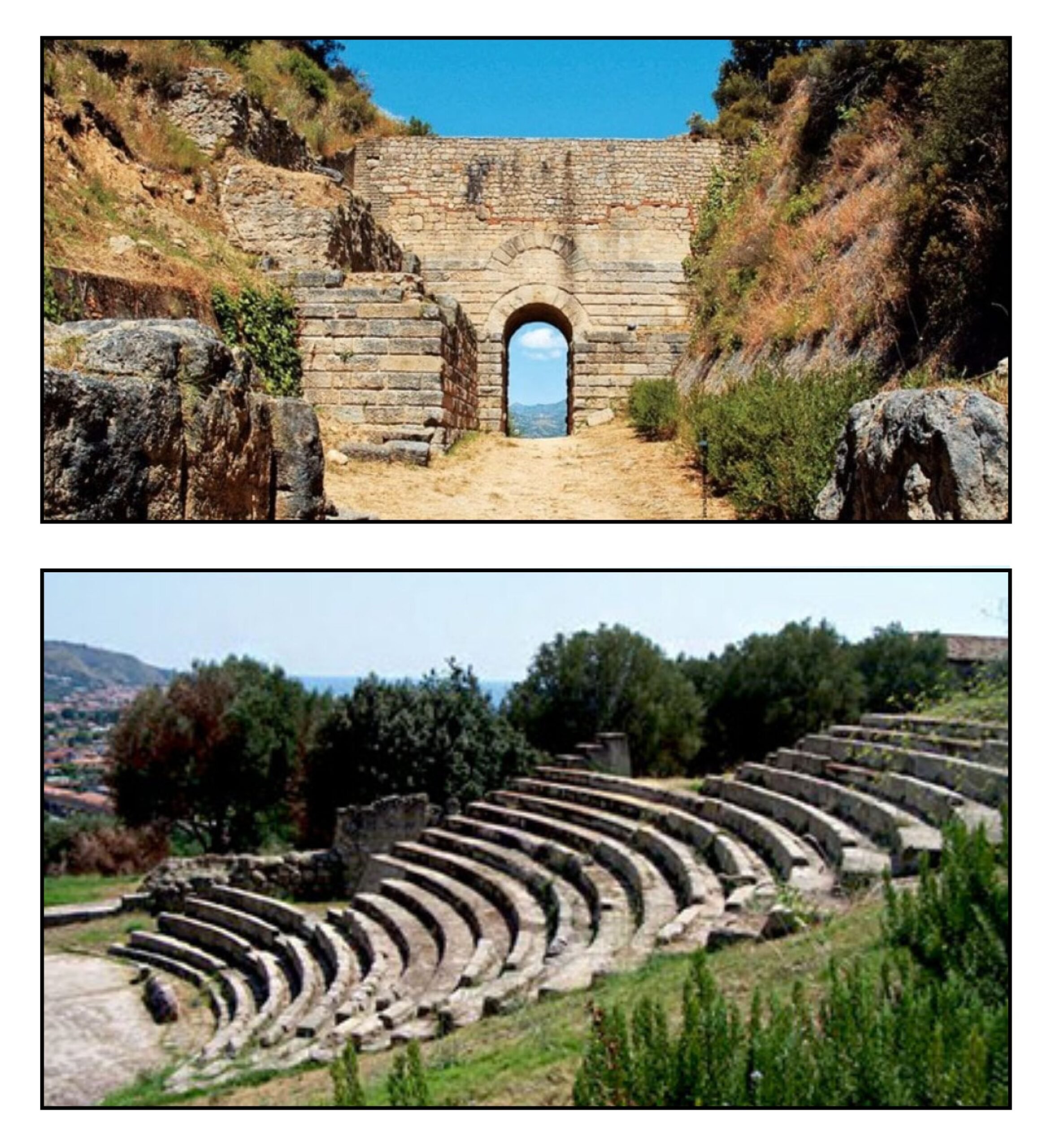

Very little is known about the life of Zeno of Elea (Palmer, 2021). Elea, modern-day Velia, was a settlement on the southwest coast of Italy, founded in 540 BCE by Greeks from Phocaea, an Ionian city on the western coast of Anatolia. The Phocians were experienced sailors who had also established colonies in Catalonia and Marseille. The Persian invasion of the Ionian cities drove most of the Phocians toward their colonies, which together with other Greek settlements formed an extensive empire called Magna Grecia. Roman ruins, including the Porta Rosa and a theater have been excavated in Velia:

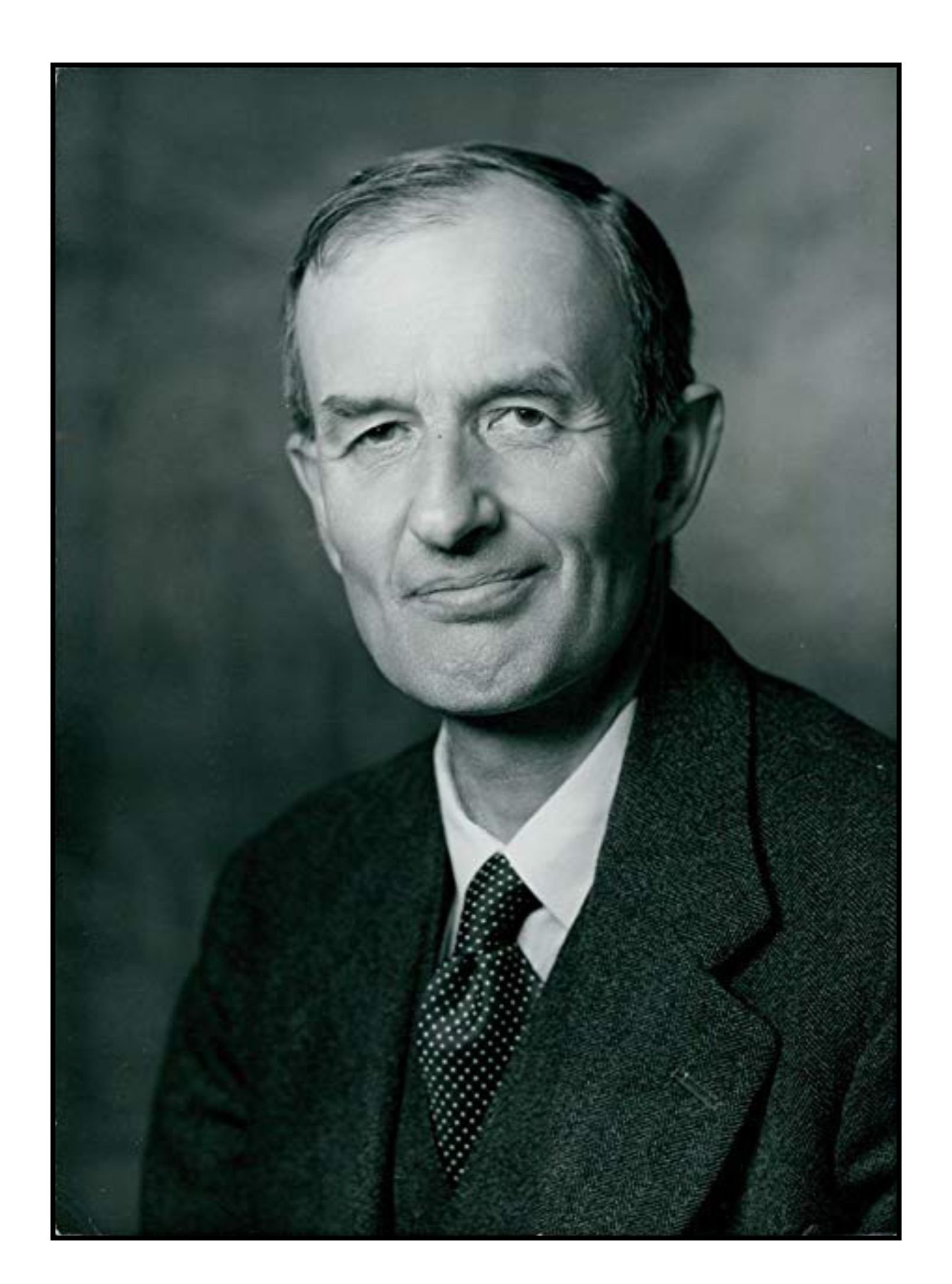

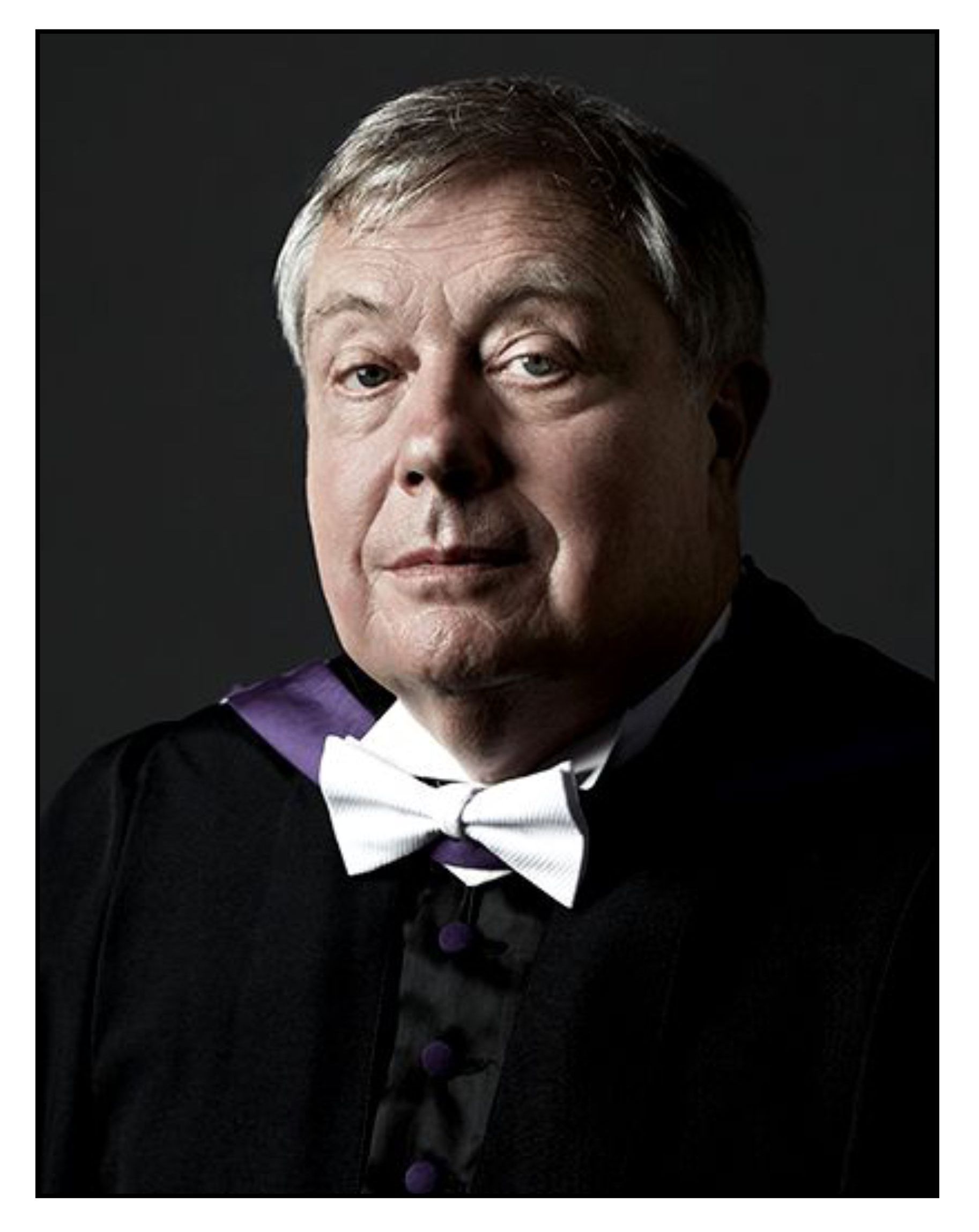

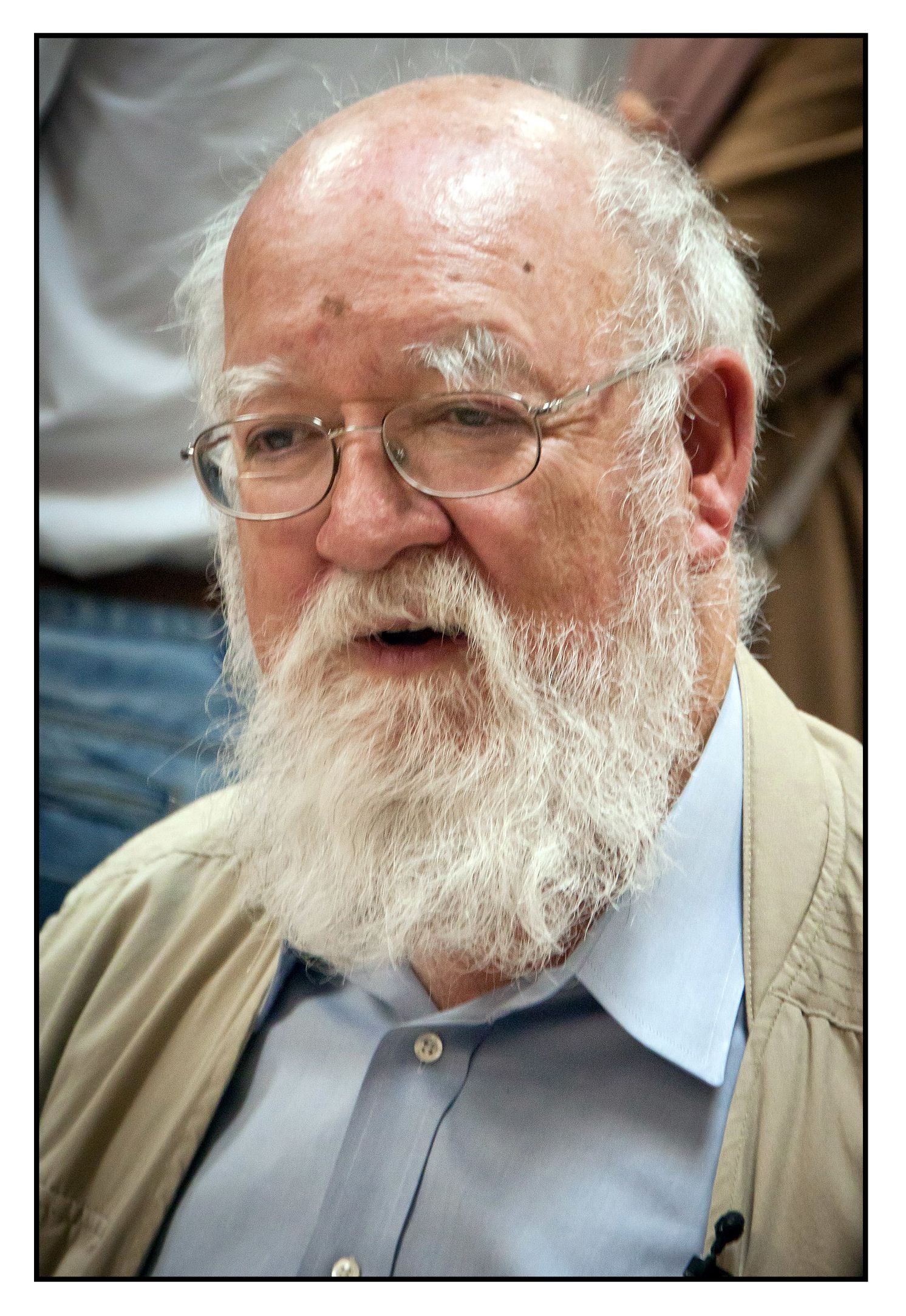

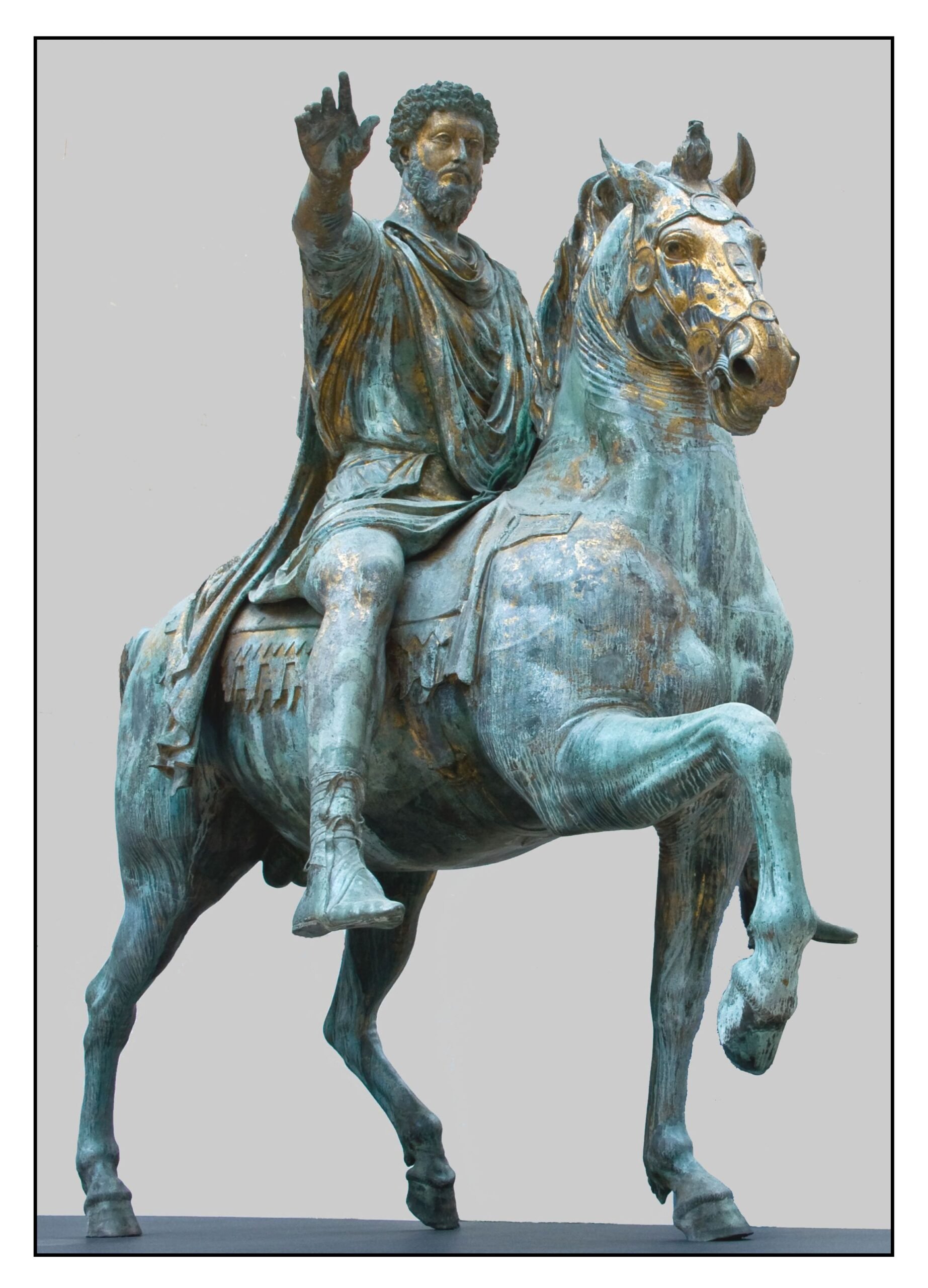

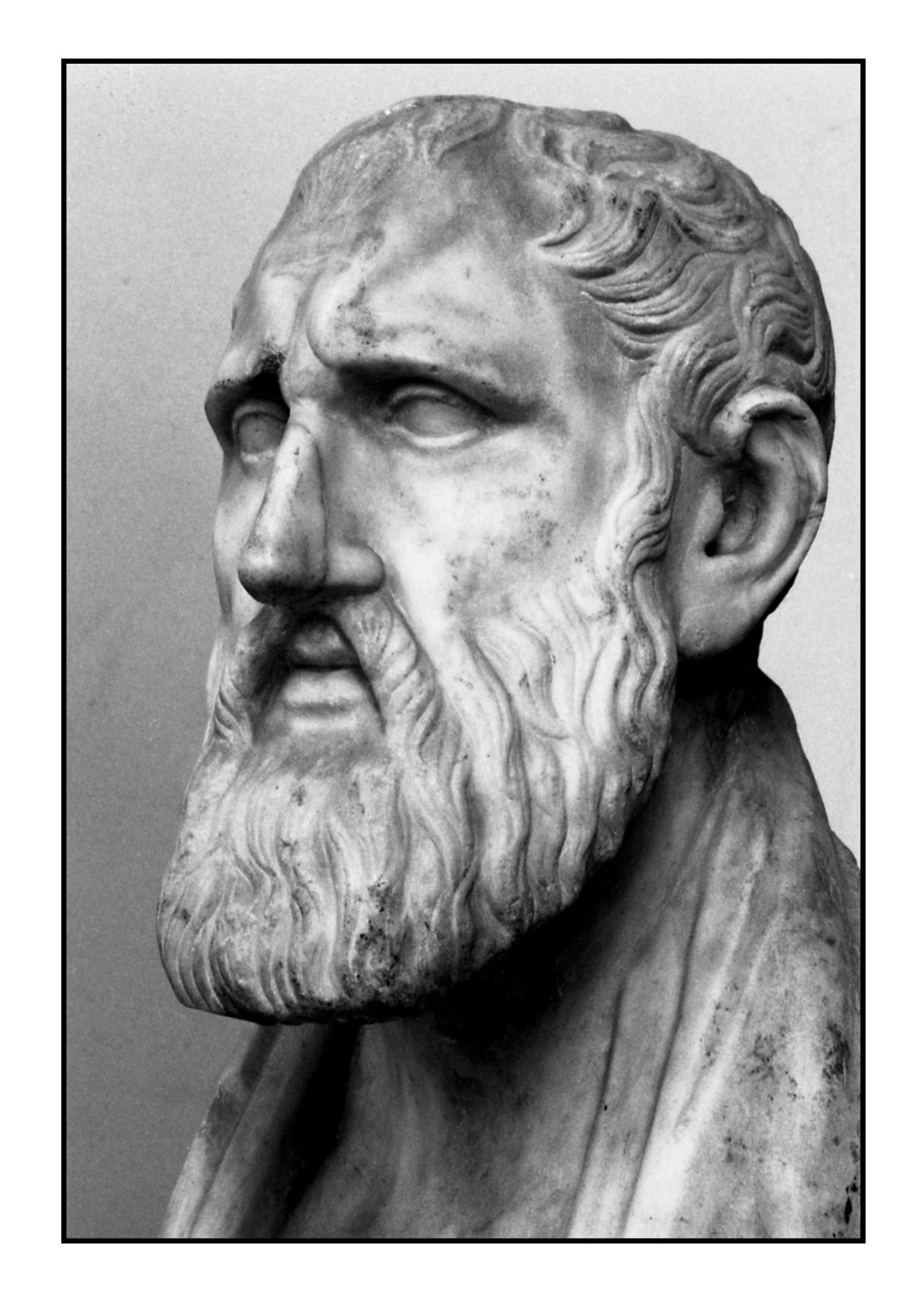

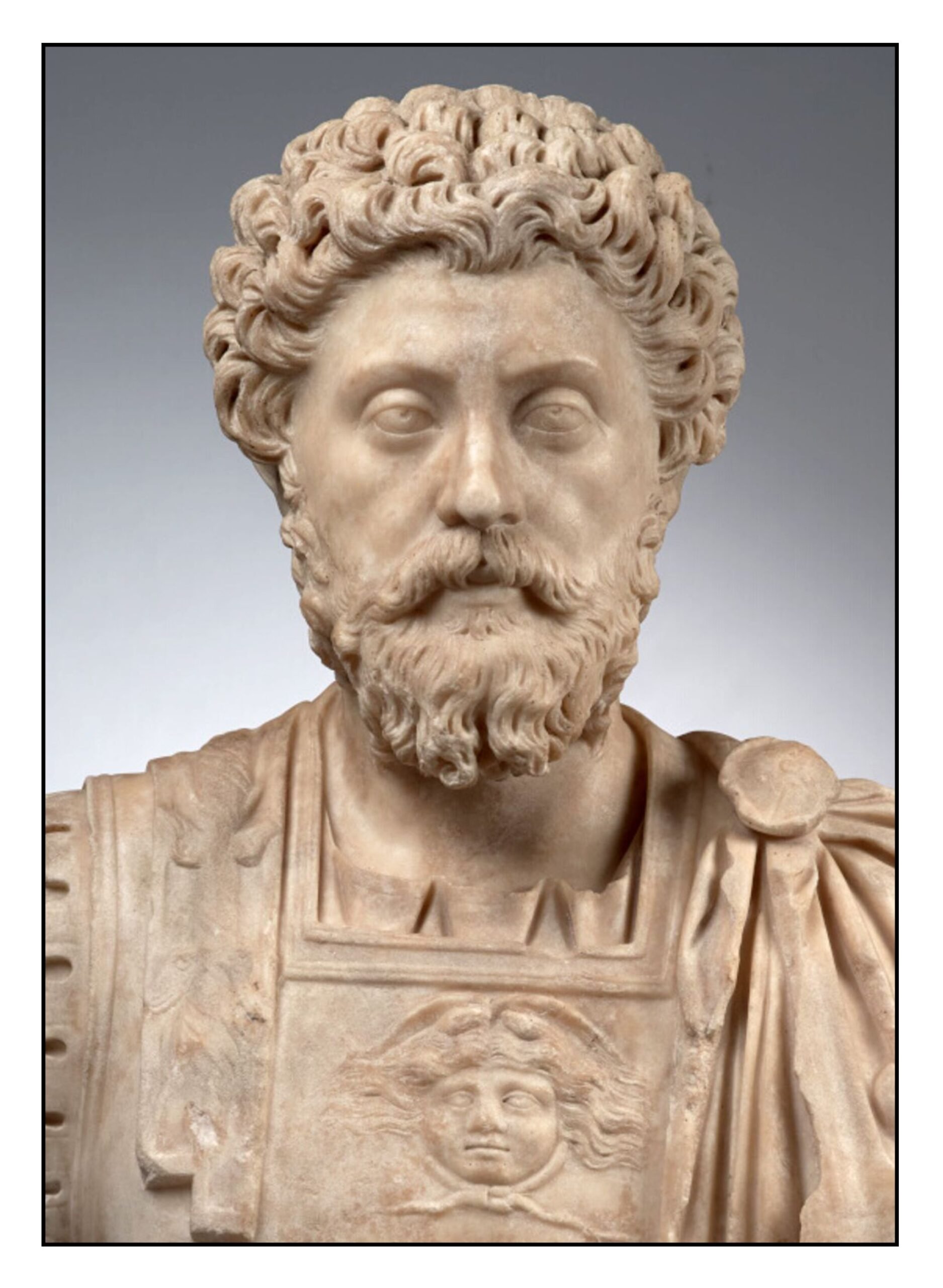

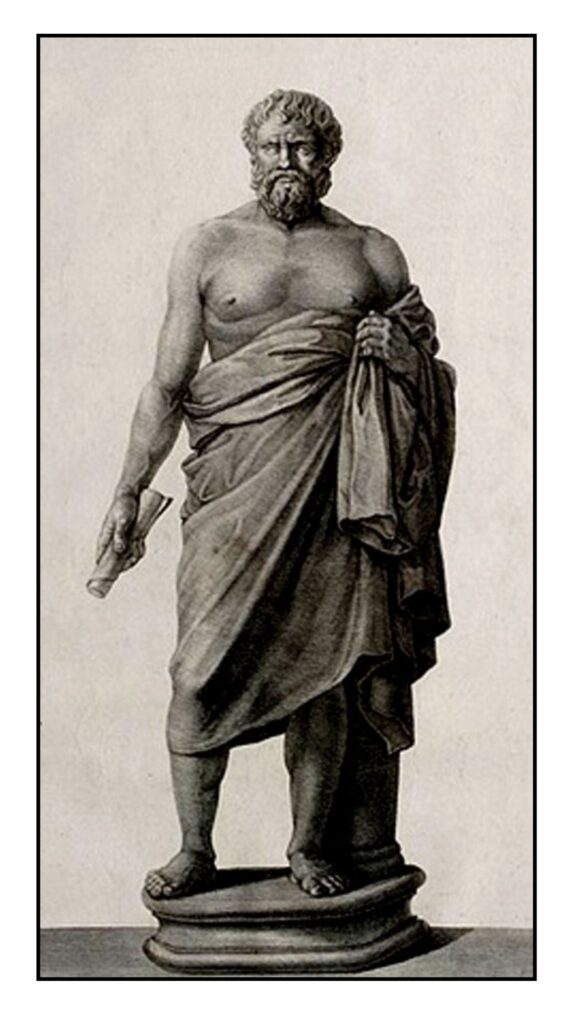

Zeno was born in about 495 BCE. He became a student of the philosopher Parmenides (?515-?440 BCE), who believed in the universal unity of being: all is one, unchanging, without beginning or end. Parmenides and Zeno may have visited Athens when Socrates was a young man, though this is uncertain. Plato’s describes their interaction in his dialogue Parmenides (~370 BCE), but Plato had not yet been born when the meeting supposedly took place. Zeno may have died under torture following his rebellion against a tyrant, though the variable accounts of his death are perhaps more fantasy than history. The Capitoline Museum in Rome has a Hellenistic statue (2nd Century BCE, illustrated on the right) which is traditionally considered a representation of Zeno. His face suggests both skepticism and humor.

A Book of Paradoxes

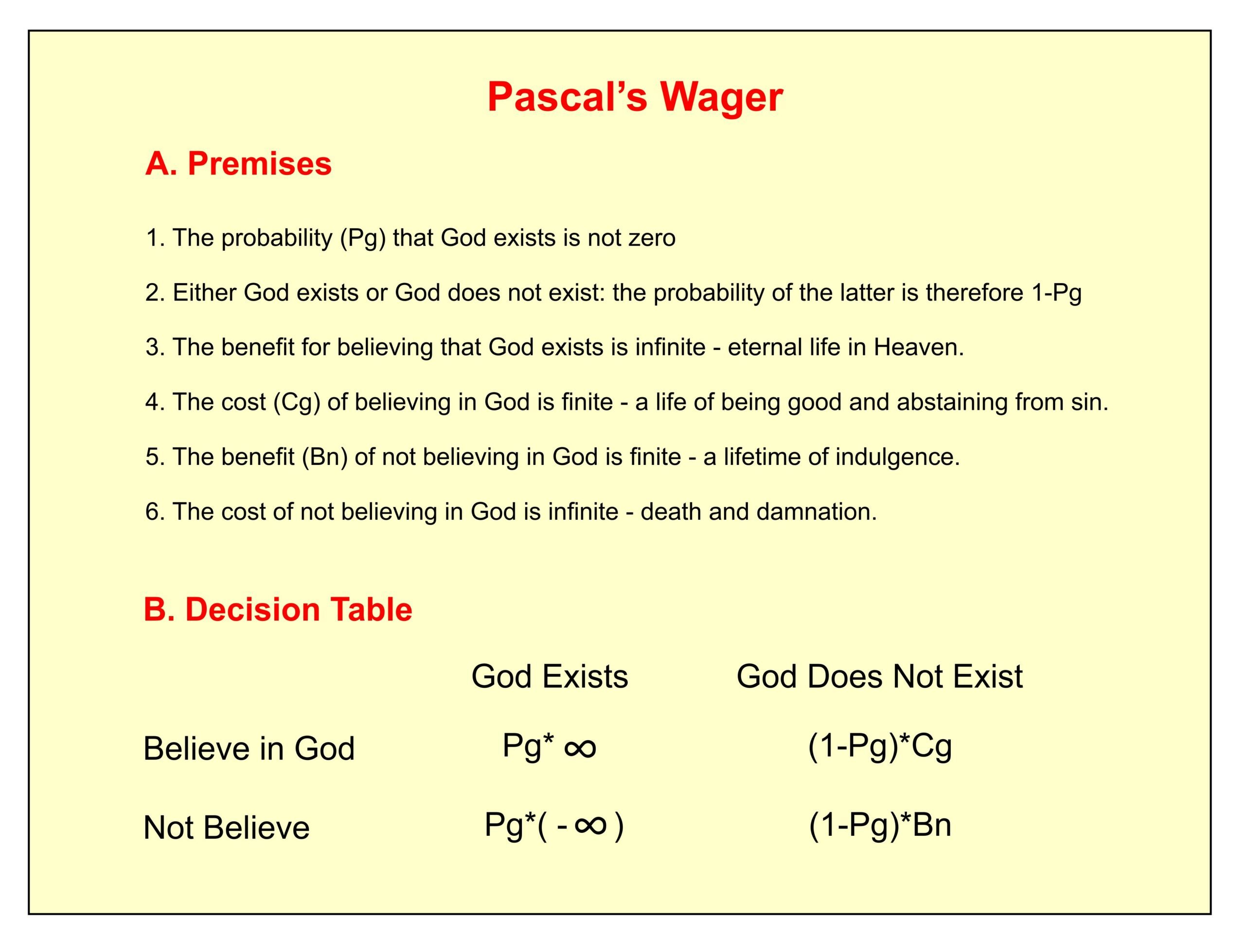

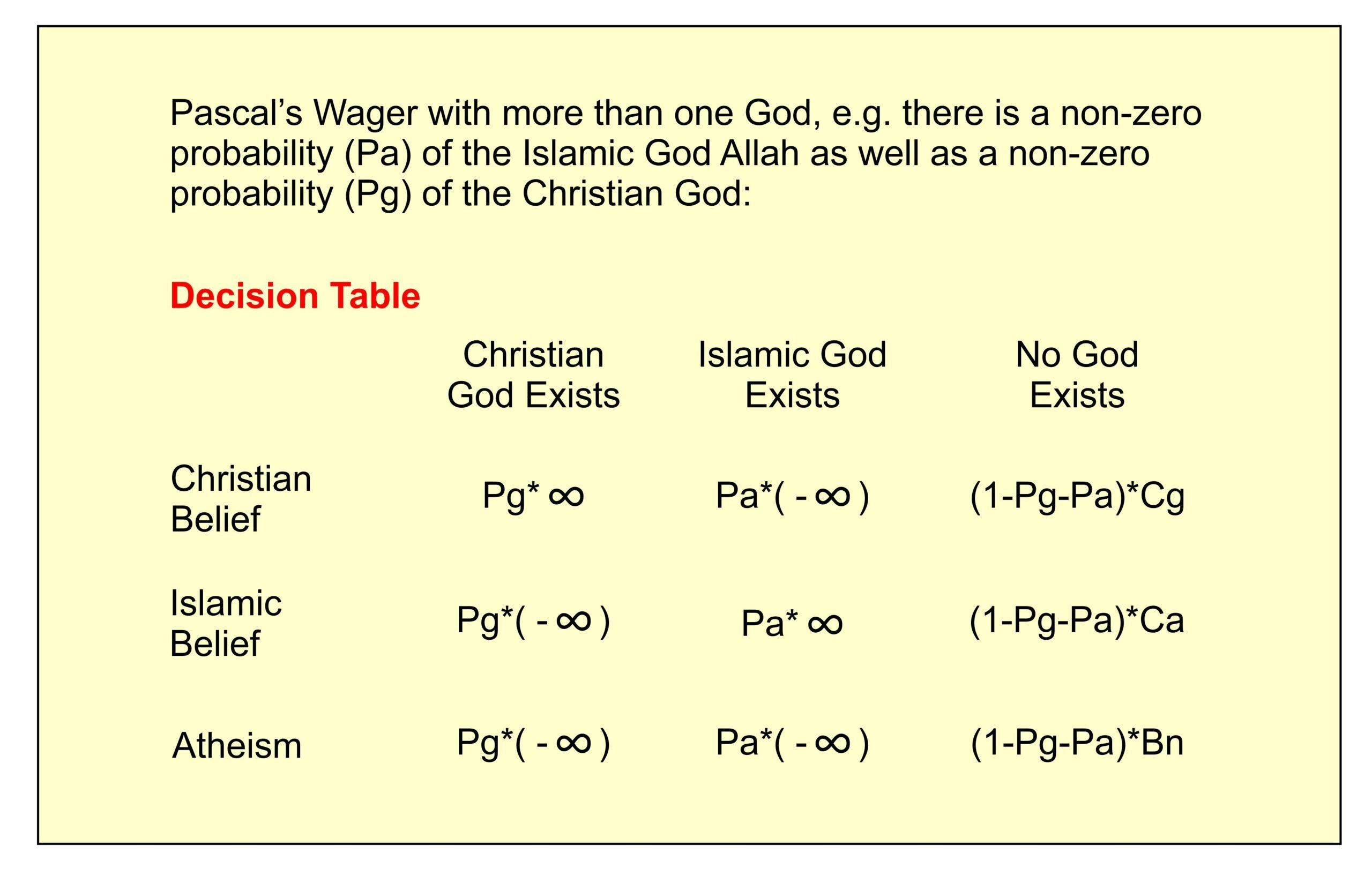

Zeno wrote a book of forty paradoxes to defend the philosophy of Parmenides (Dowden, 2023). Unfortunately, the book did not survive and all we know about its contents are brief references in later writings by authors who may not have understood Zeno’s thinking. A paradox is a logical argument that leads to a conclusion at odds with (para, beside or beyond) accepted opinion (dox) (Strobach, 2013). A paradox may be used to demonstrate that accepted opinion is wrong, or at least open to contradictory interpretation. However, the usual intent of a paradox is to show that the premises of the argument must be incorrect since the conclusion is so obviously impossible. This is a variant of the reductio ad absurdum. Any paradox therefore presents us with a choice:

either the conclusion is not really unacceptable, or else the starting point, or the reasoning, has some non-obvious flaw. (Sainsbury, 2009, p 3)

One problem with Zeno’s paradoxes is that we do not know how to interpret them because we do not know how he intended them to be used. The following paragraphs will consider the two most famous of Zeno’s paradoxes from the point of view of modern science and mathematics.

Achilles and the Tortoise

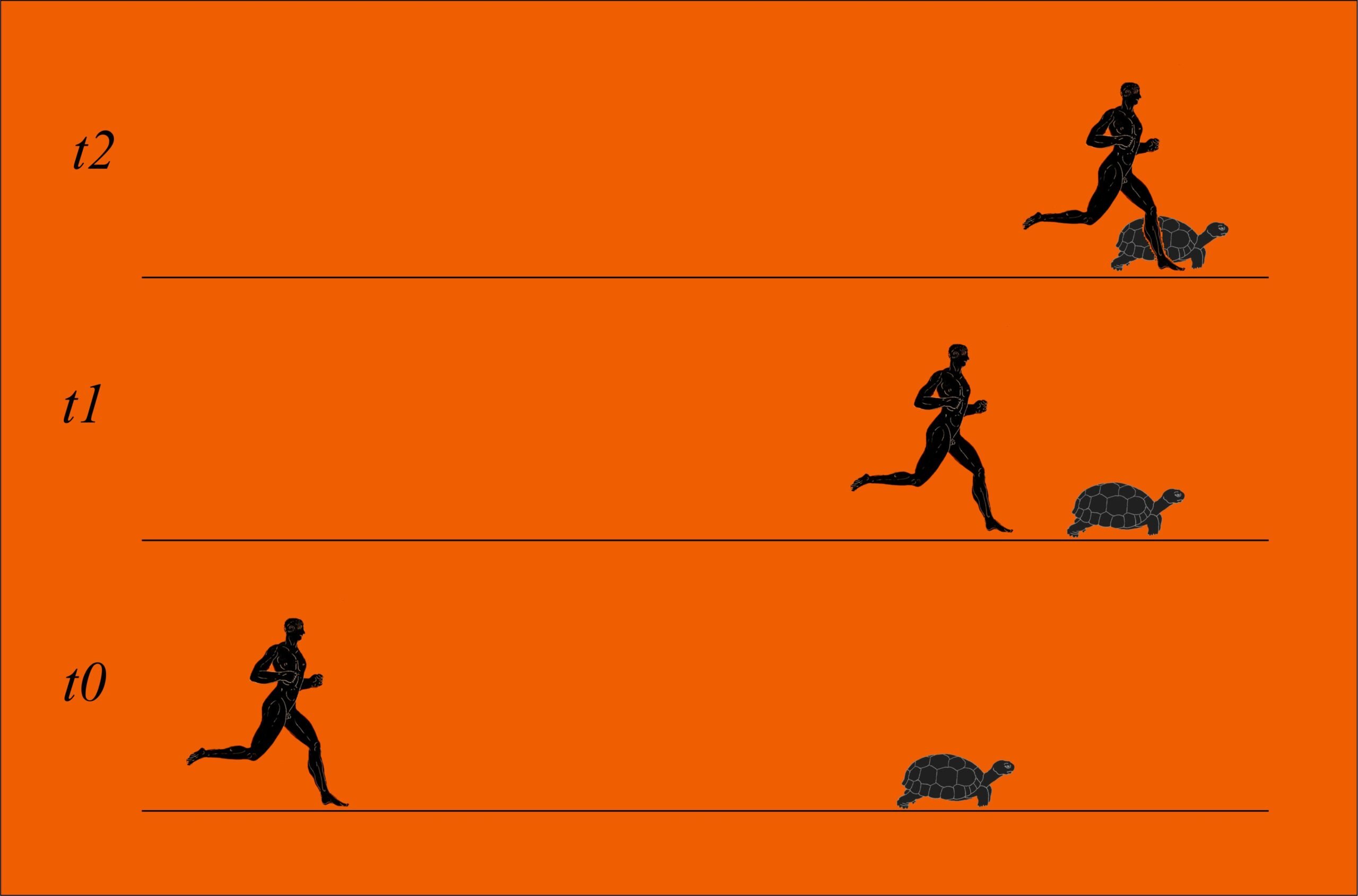

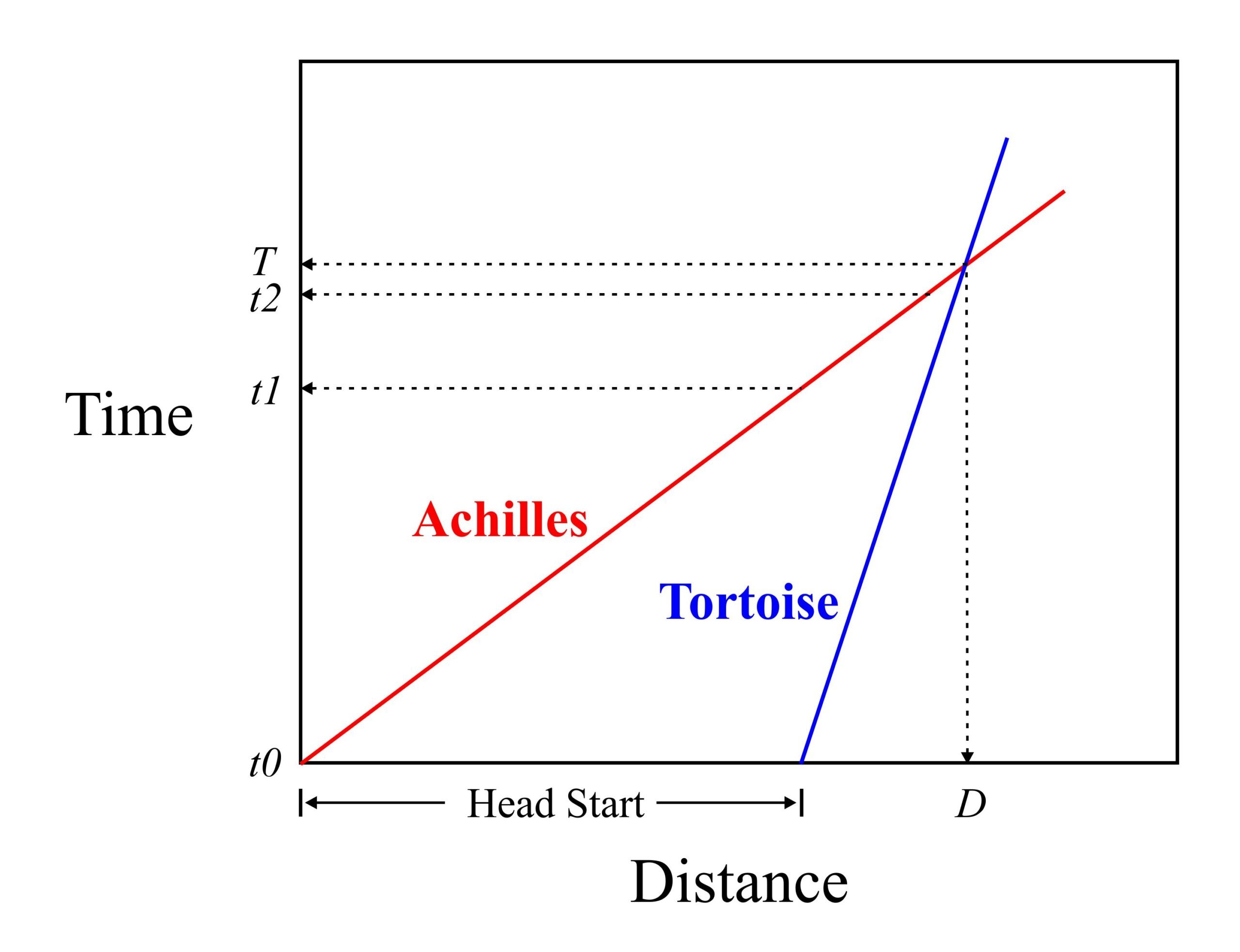

The original paradox appears to be have involved two runners one faster than the other. Their identification with Achilles and the Tortoise occurred later. In a race the speedy Achilles is attempting to pass a slow Tortoise, who has been given a head start. In order to catch up with the tortoise Achilles must first reach the point where the turtle began the race (t0). However, by then (t1) the tortoise has already moved ahead, albeit by a smaller distance than Achilles has traversed. Achilles must then reach the point to which the Tortoise had advanced. He can cover this extra distance by t2 but again the Tortoise has already moved ahead. Achilles continues to reach the point to which the Tortoise has advanced only to find that the Tortoise has already moved further on. Achilles can therefore never pass the Tortoise. The first three episodes of this infinite train are shown below. For ease of illustration, Achilles is made to run about 4 times faster than the Tortoise:

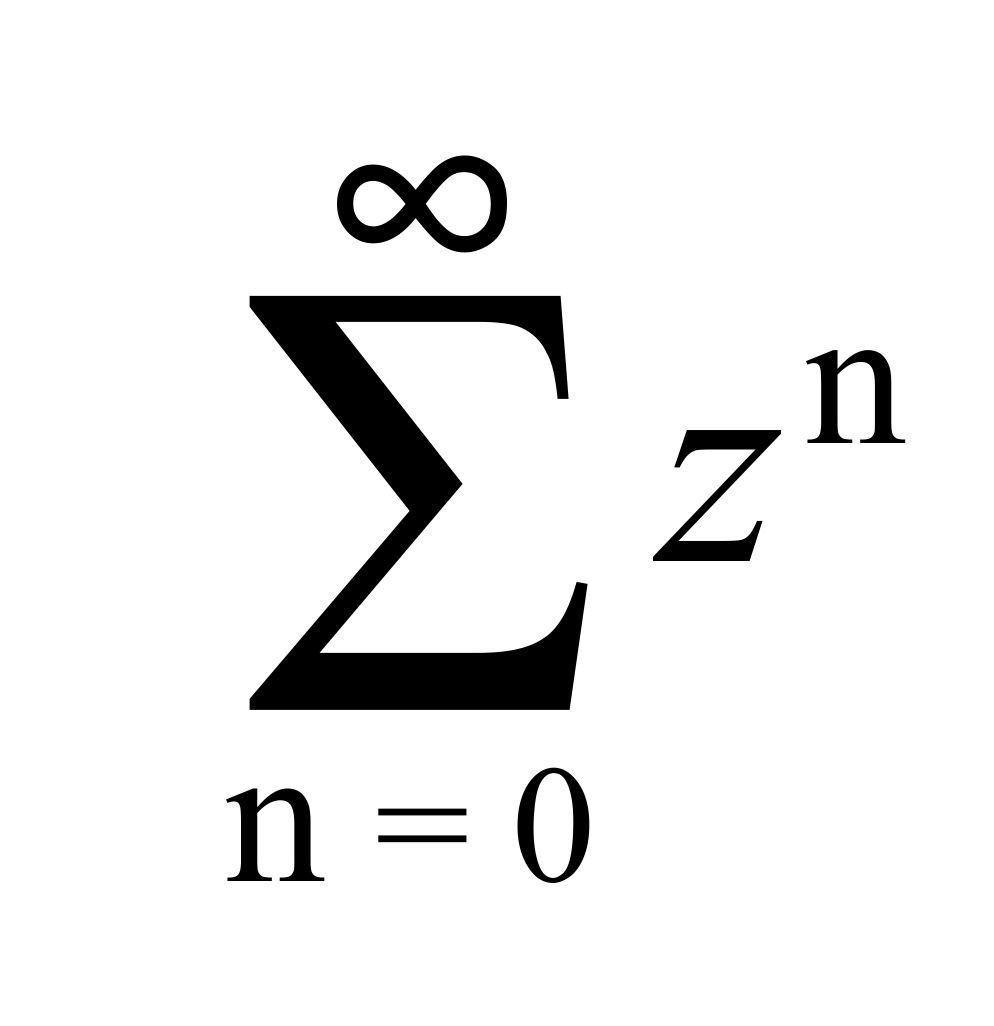

The paradox basically proposes that the time taken by Achilles to catch up with the Tortoise is composed of an infinite number of intervals. Even though the later intervals may become vanishingly small, an infinite number of intervals would take an infinite amount of time. Modern mathematics, however, has shown that infinite series like that of Achilles and the Tortoise can have a finite sum. An infinite geometric series of the form

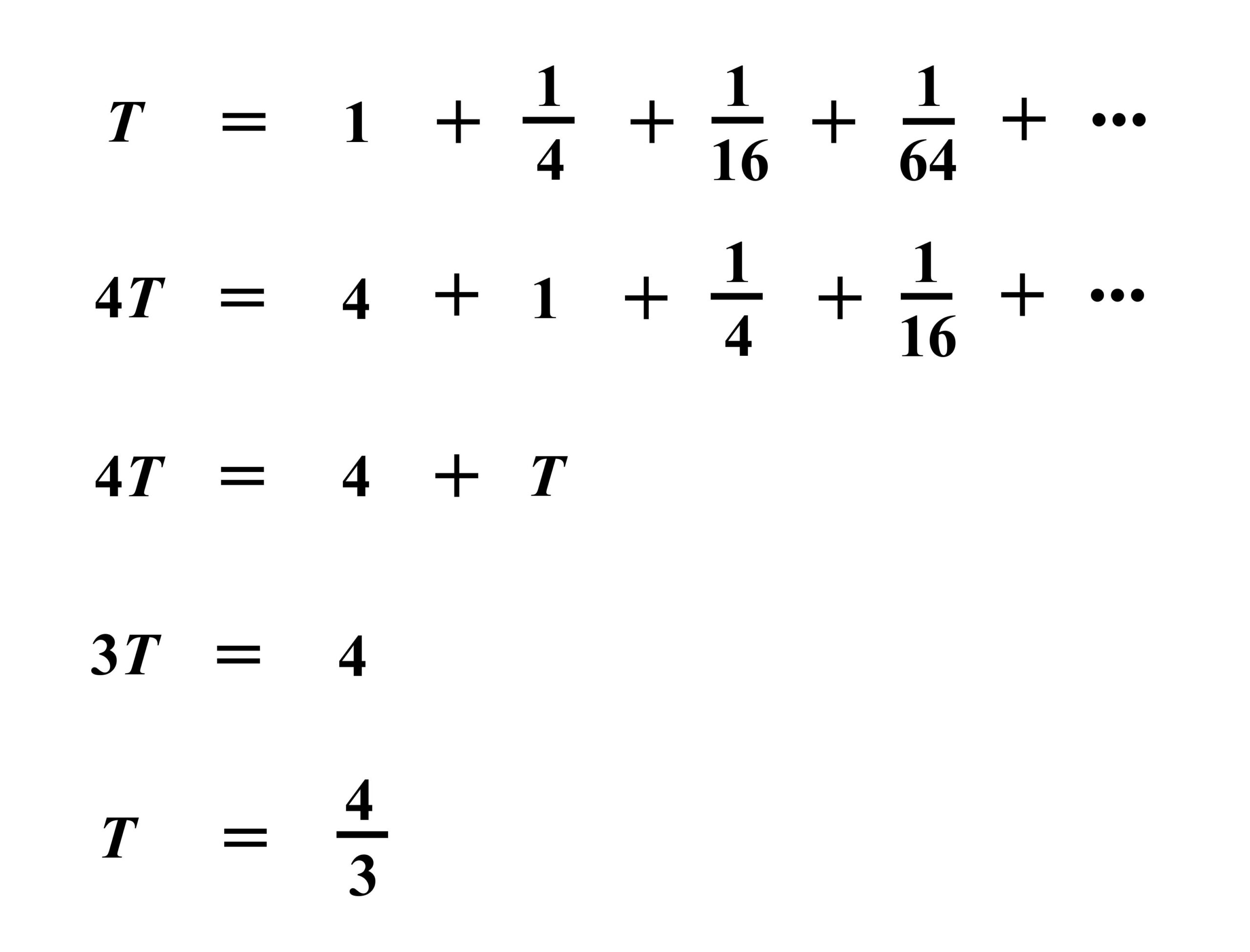

sums to a finite amount 1/(1-z) if the absolute value of z is less than 1. For the example that we have been using the value of z is 1/4, i.e., the ratio of the velocities between Tortoise and Achilles. The sum of the series is thus 4/3.

This is demonstrated through the following equations. The sum of the series (T) is equal to the time taken to cover the distance of the Tortoise’s head start (for simplicity this is made equal to 1) plus the time taken to cover the distance that the Tortoise has covered in the meantime (equal to 1/4 since for our illustration Achilles travels 4 times faster than the Tortoise) plus 1/16 for the next abortive catch-up, and so on to infinity (…). The equations demonstrate that the sum of the series equals 4/3.

The paradox can also be solved using algebraic equations. One can assume Achilles catches up with the Tortoise at a time T after travelling a distance D. The equation for Achilles is

D = T*Va where Va is the known velocity of Achilles

And for the Tortoise is

D = T*Vt + H where H is the distance of the head start and Vt is the velocity of the Tortoise

Combining the two equations we have

T*Va = T*Vt + H

Thence

T = H / (Va – Vt)

In our example Vtis 1/4 of Va

T = H / (3/4*Va)

Or 4/3 the time that it takes Achilles to travel the distance of the Tortoise’s head start.

These calculations can be represented graphically with distance plotted on the horizontal axis and time on the vertical axis:

A simple mathematical view of Zeno’s paradox is to set the frame of reference to the moving Tortoise and to calculate the speed of Achilles relative to this reference. In our example, the speed of Achilles relative to the Turtle is 3. This is 3/4 the speed of Achilles relative to the absolute reference and thus it will take Achilles 4/3 the time to catch up with the Tortoise.

These mathematical approaches allow us to understand the movements of Achilles and the Tortoise, to determine where they will be as time passes, and to calculate when Achilles will finally pass the Tortoise. However, they do not really resolve the paradox as presented by Zeno. If space and time are infinitely divisible into points and instants, it will take Achilles an infinite number of acts to catch up with the Tortoise, and an infinite number of acts will take forever (Black, 1970).

We do not know Zeno’s original intent in formulating his paradoxes of motion. He probably did not wish to prove that motion is impossible, and that our perception of moving things is illusory. Rather, he likely wanted to prove that space and time are continuous and cannot be divided into discrete points and instants. This would be in keeping with the monism of his teacher Parmenides. Bertrand Russell (1926, p 174) stated that

The conclusion that Zeno wishes us to draw is that plurality is a delusion and that spaces and times are really indivisible.

However, Russell goes on to propose that space and time may be infinitely divisible if we properly understand infinity.

Zeno’s Arrow

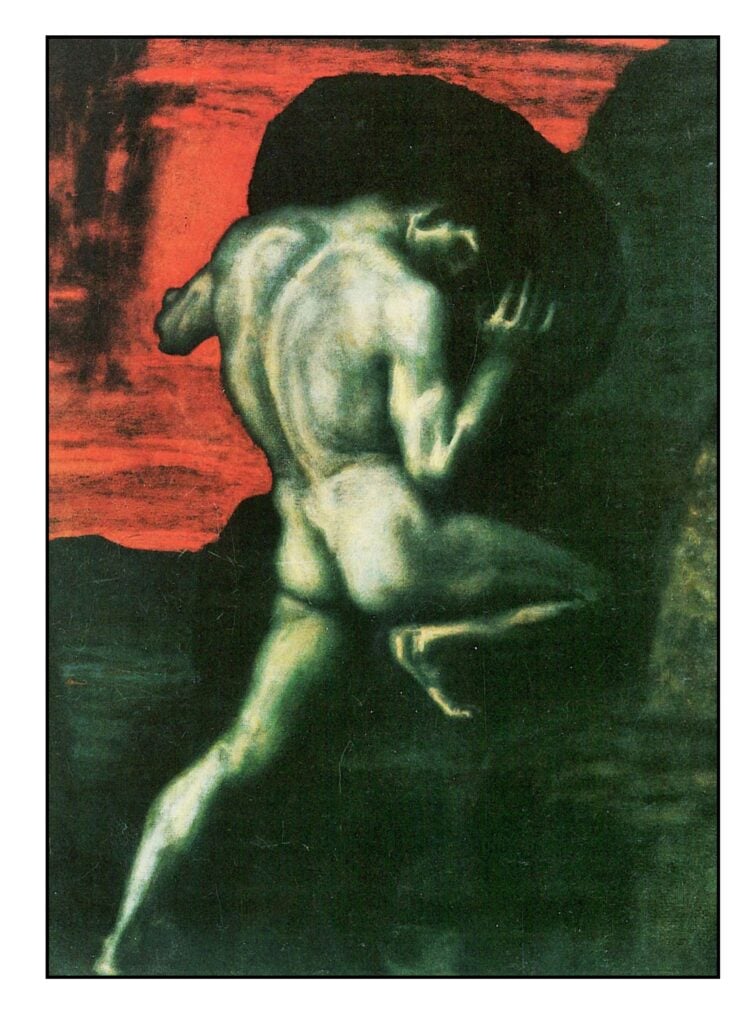

At any instant of time a flying arrow will occupy a space equal to its own size and therefore show no evidence of movement. Its flight is therefore a succession of rests. While it is moving, the arrow is always stationary.

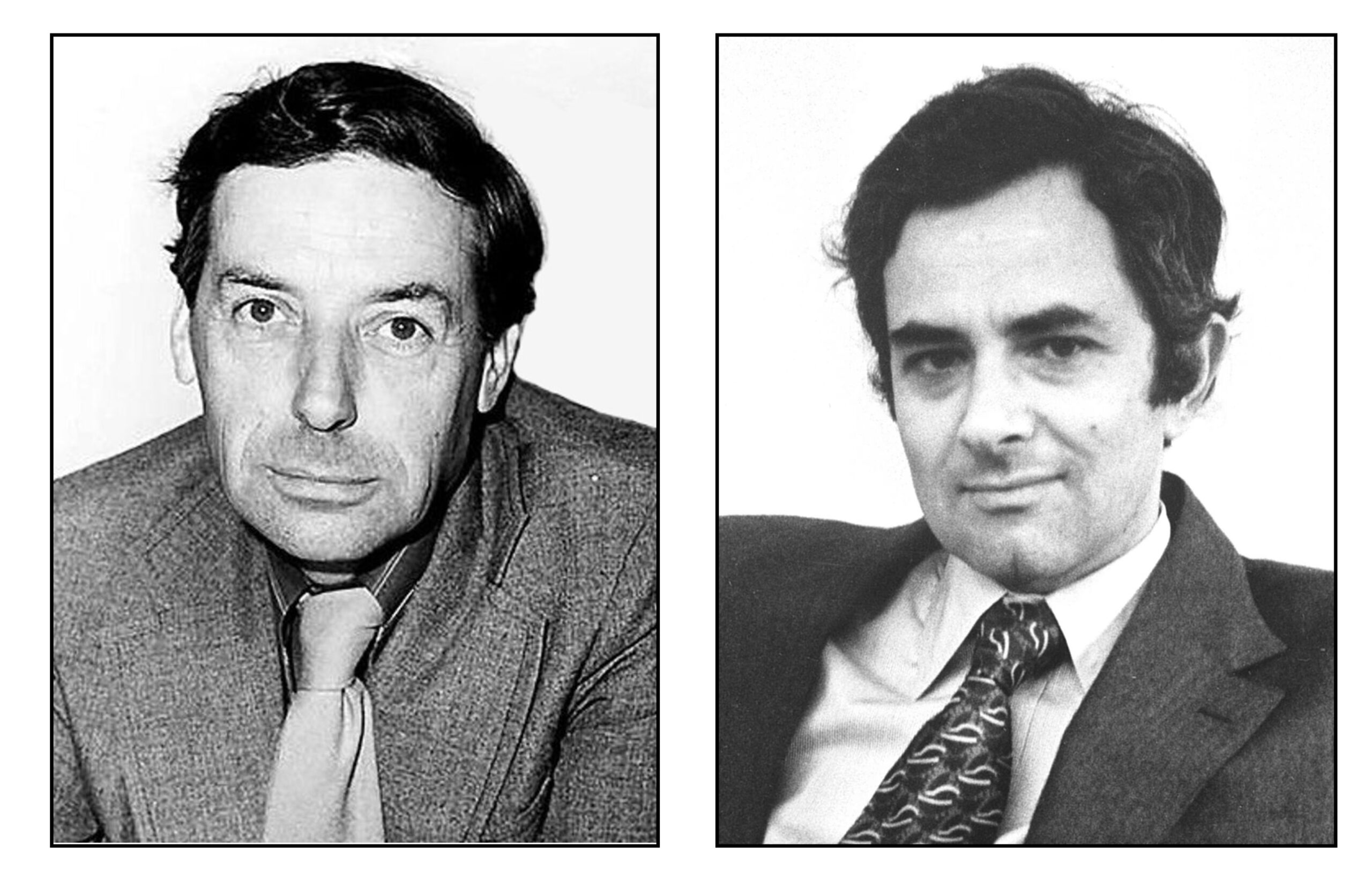

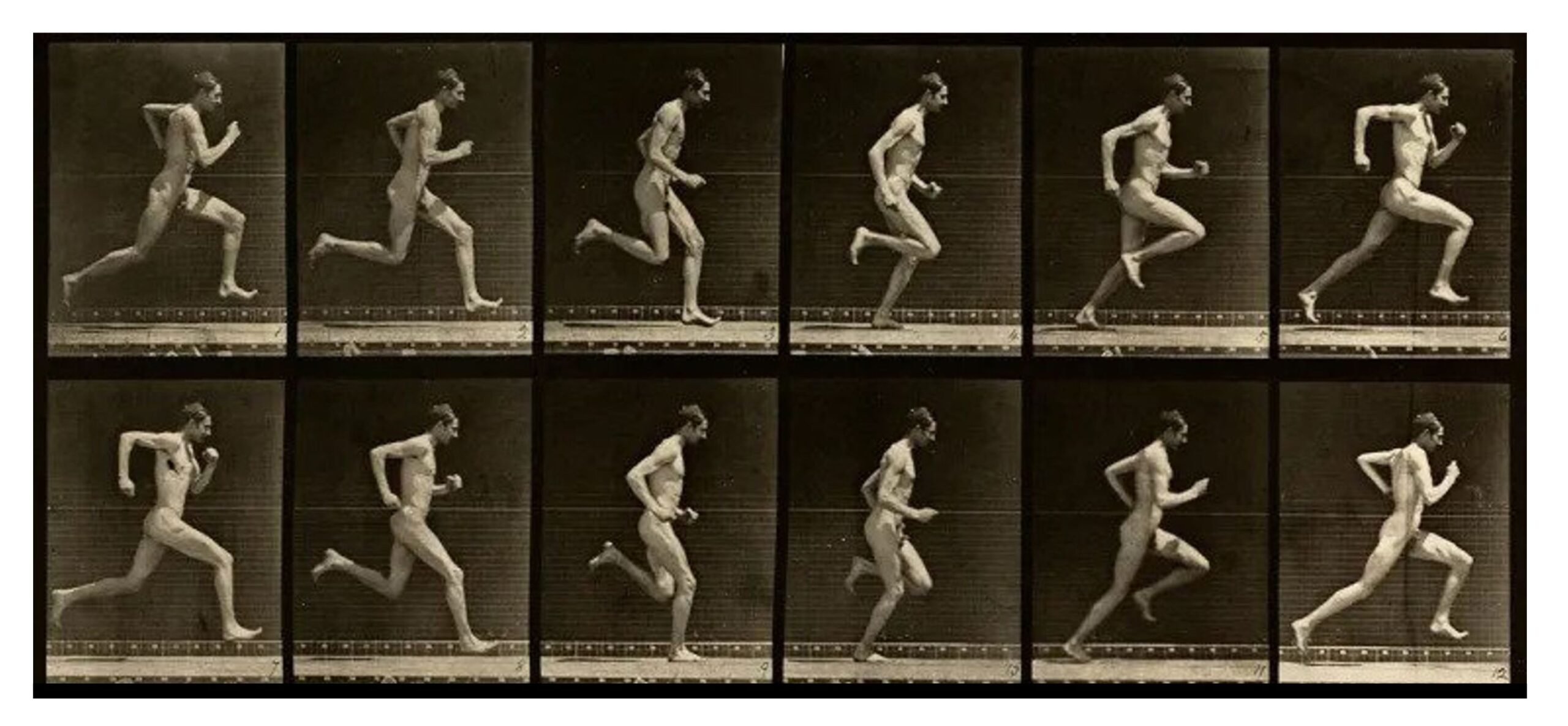

Zeno had not observed an arrow at an instant of time: he could only imagine it. Modern high-speed photography can record moving objects at an instant of time. If the exposure time is very small, they appear unblurred, or completely stationary. The observer cannot tell that the object is moving from its instantaneous appearance. The first person to record motion using high-speed photography was Eadweard Muybridge (1840-1904). The following set of photographs of a running man were likely taken in the 1870s and printed in 1887.

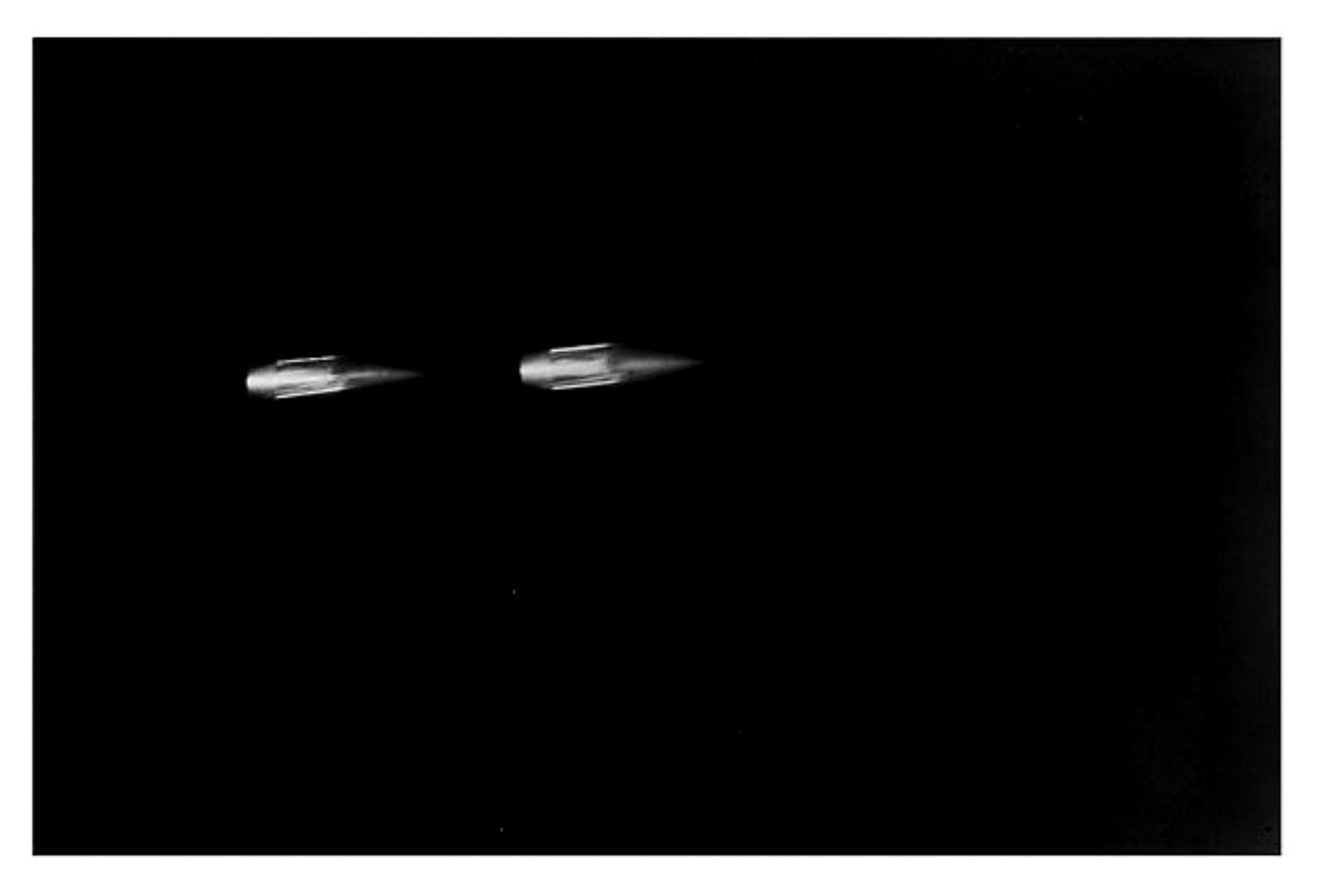

The development of the stroboscope which could present brief flashes of bright light allowed photographers such as Harold Edgerton (1903-1990), also known as “Papa Flash,” to examine very rapidly moving objects. The following photograph from the 1950s shows a moving bullet “caught” at two instants by two stroboscopic flashes separated by only a brief time (probably of the order of 50 microseconds).

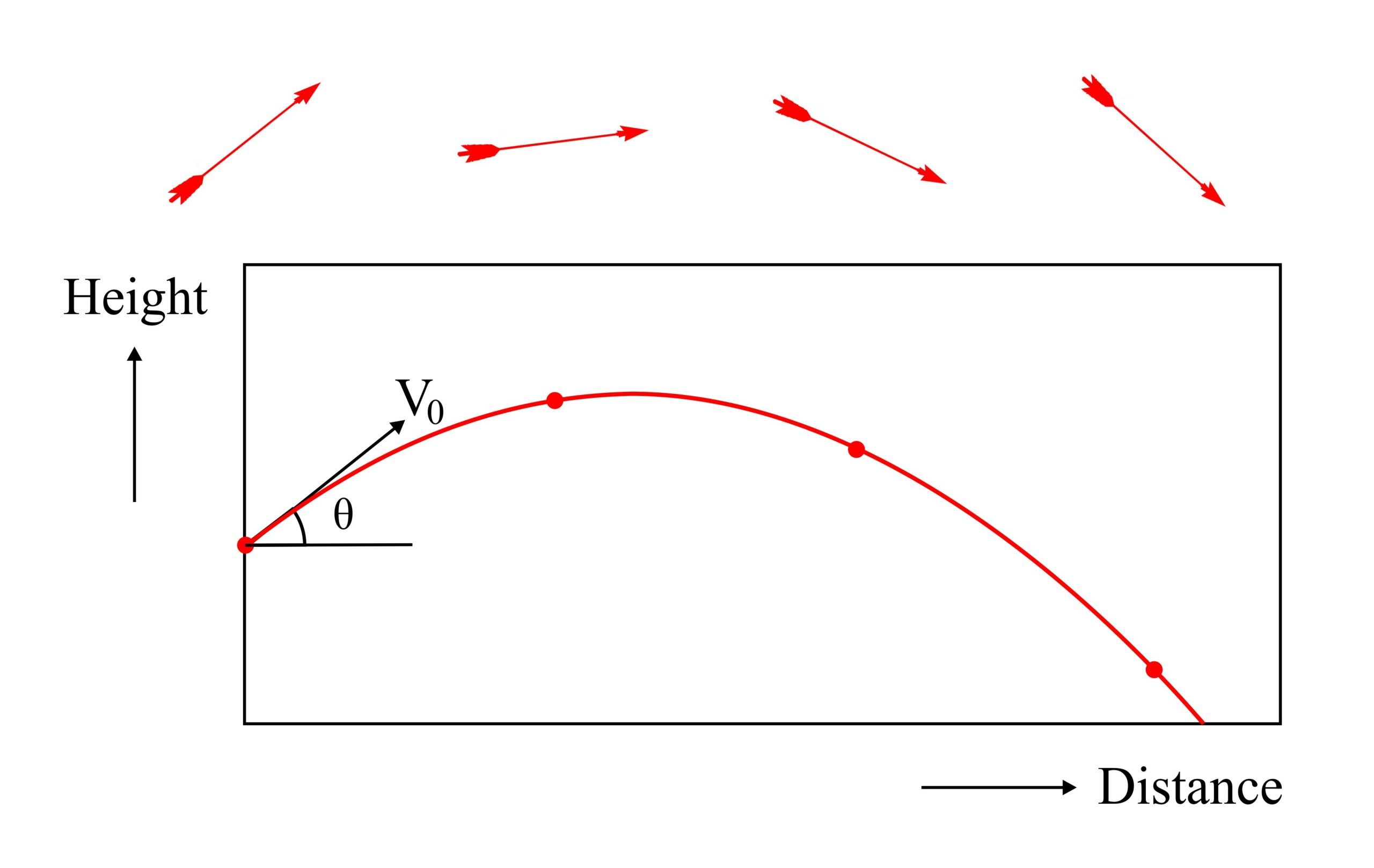

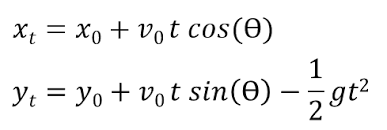

At first glance, modern science apparently confirms the conclusion Zeno’s Arrow Paradox: at any instant of time a moving arrow, man or bullet is stationary. However, just because something looks stationary does not mean that it does not have velocity. The trajectory of the arrow can be represented by two functions denoting its horizontal (x) and vertical (y) position:

The parabolic trajectory is determined by the initial velocity (V0) of the arrow as it is released from the bow, the angle (θ) at which it is released, its initial height above the ground (y0), and downward acceleration caused by gravity (g). The following diagram shows a sample trajectory, together with views of the arrow at four instants of time. Note that the formulae do not consider the (very small) effects of friction and treat the horizontal velocity of the arrow as constant. The horizontal axis can therefore also represent time.

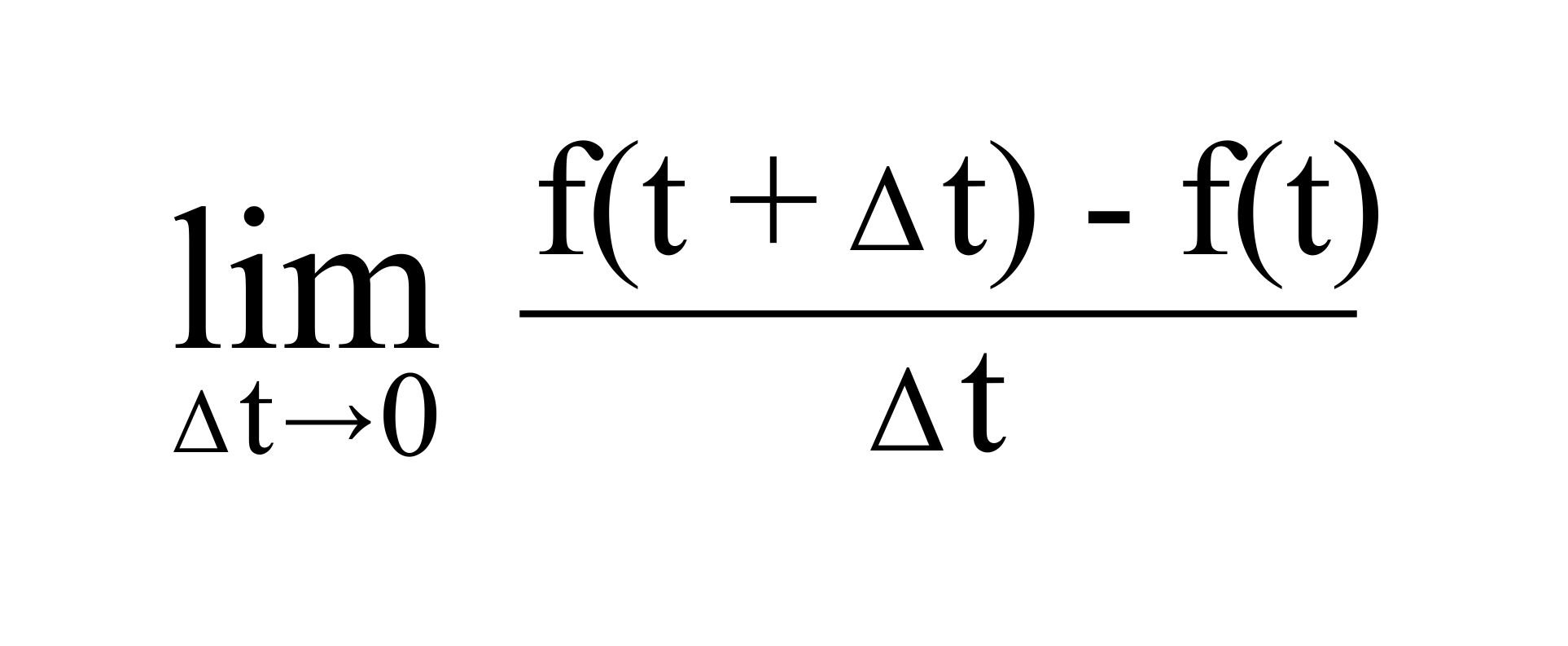

The invention of the calculus by Newton and Leibniz allowed us to calculate the velocity of a moving object at any instant in time. If the distance travelled can be represented by a function (f), the velocity at any instant (t) can be calculated by seeing how far the object travels in a tiny period of time (Δt)

The limit as Δt approaches zero – the derivative of the function – is the object’s instantaneous velocity. At any instant of time the object shows no evidence of movement, but it still has velocity. Though it appears stationary, it still moves.

The calculus allows us to calculate the velocity of the arrow at any instant (Reeder 2015). However, Zeno’s paradox calls into question the idea of discrete instants in time. Motion is continuous; it is not a succession of stationary positions. William James (1910, p. 157):

Zeno’s arguments were meant to show, not that motion could not really take place, but that it could not truly be conceived as taking place by the successive occupancy of points. If a flying arrow occupies at each point of time a determinate point of space, its motion becomes nothing but a sum of rests, for it exists not, out of any point; and in the point it doesn’t move. Motion cannot truly occur as thus discretely constituted.

Time and Space

Zeno’s paradoxes have been discussed extensively (Dowden, 2013; Grünbaum, 1967; Huggett, 2018; McLaughlin, 1994; Sainsbury, 2009; Salmon, 1970; Strobach, 2013). Most writers suggest that modern mathematics can handle the paradoxes: infinite series may sum to a finite amount and instantaneous velocities can be assessed with the infinitesimal calculus.

However, the nature of time and space remain imperfectly understood. A particular problem involves what might be considered the smoothness of these dimensions. Achilles does not run through an infinite set of decreasing distances to catch up with the Tortoise. Rather he runs smoothly and quickly passes the Tortoise. The arrow does not move from one stationary position to the next as if it were in a movie flickering at a slow frame-rate. The arrow moves smoothly from the bow to the target.

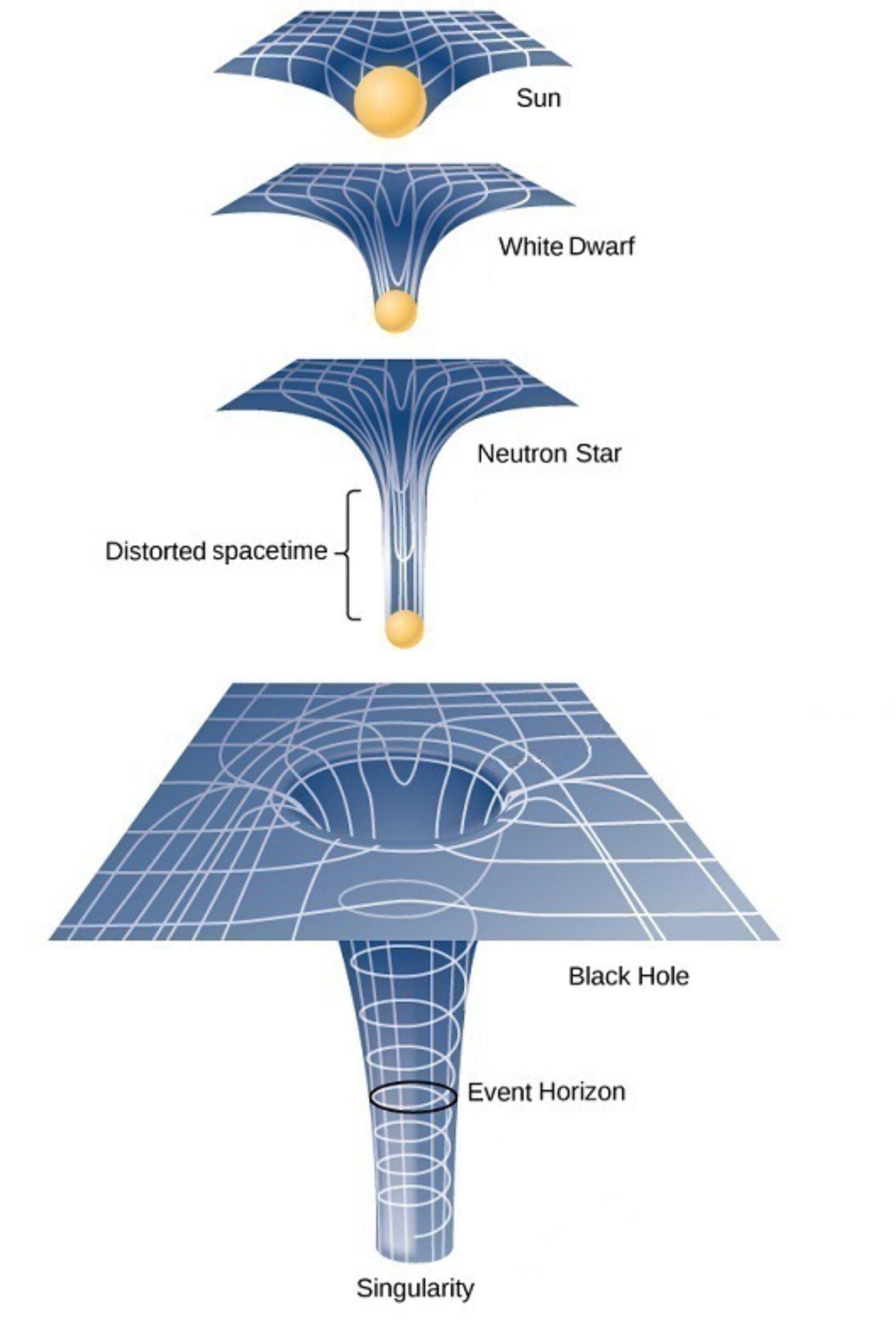

Modern conceptions of space and time propose that they are not absolute (e.g., Rovelli, 2018; Markosian et al., 2018). The fabric of space and time can be altered by gravity. A large mass like our sun will distort the adjacent space. Light travelling near such a mass will be deflected by the resultant curvature. A large mass also alters time, which passes more rapidly the closer one is to the mass. It is difficult to understand how such elastic dimensions can be represented by discrete points. The effects of gravity are illustrated in the following diagram, where the four-dimensional fabric of space is shown as a 2-dimensional mesh:

Time’s Arrow

Although we often consider our universe as existing in four dimensions, the dimension of time is distinct from the three spatial dimensions. Though we can move back and forth in space, we can only move forward in time.

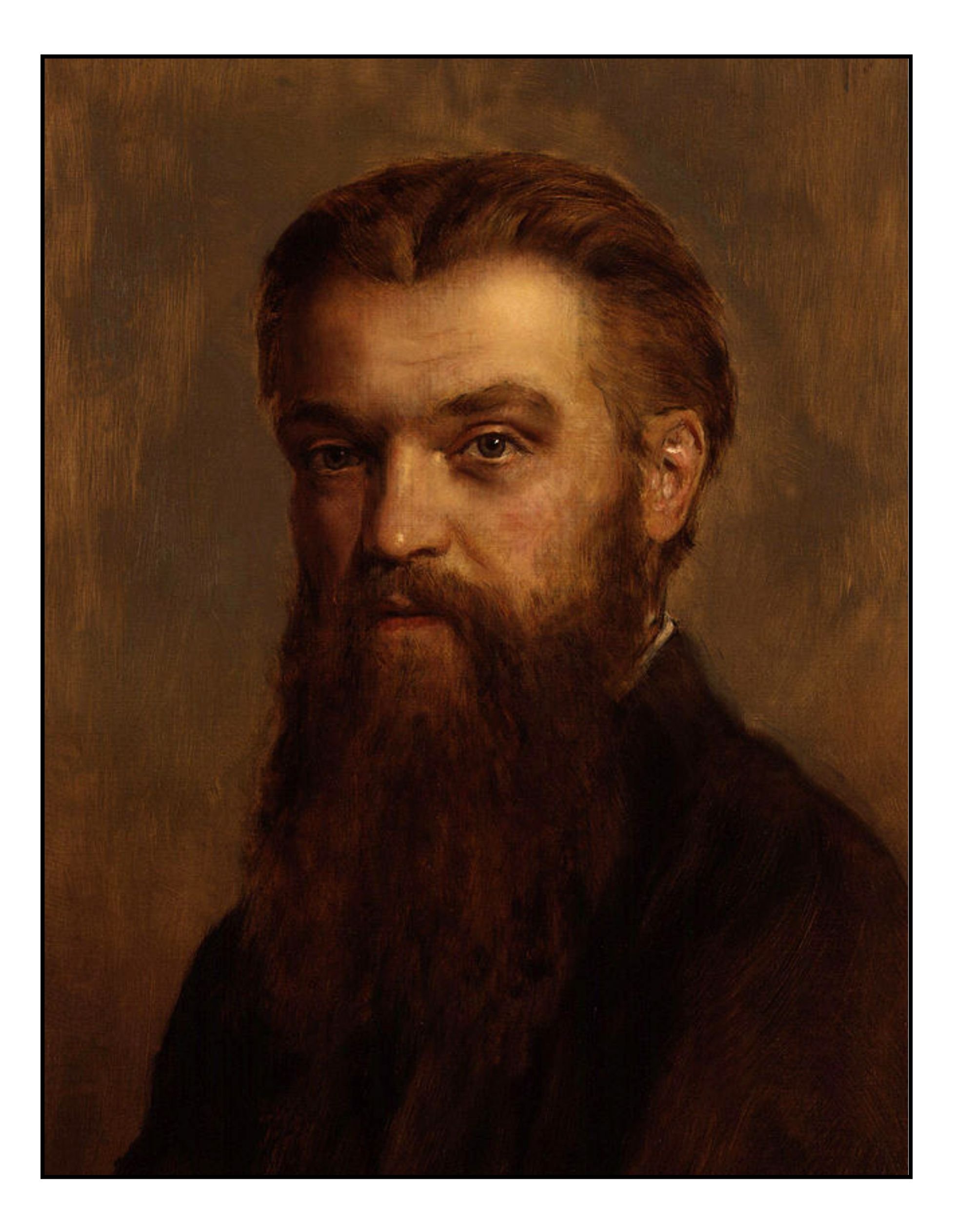

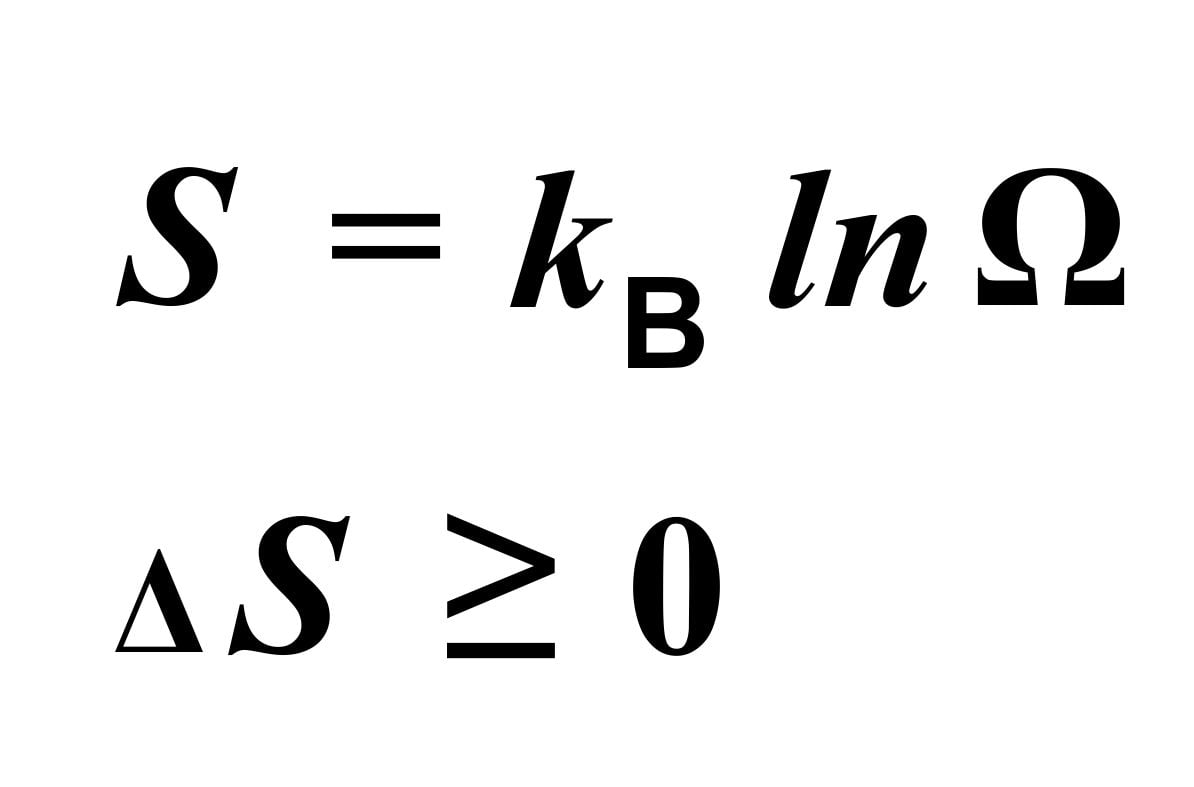

Studies of statistical mechanics demonstrated that the state of a system can be described by the organization of its components. With the passage of time, this state can only change towards increasing disorder. In the formulation of Rudolf Clausius (1822-1888) of this disorder was called “entropy” (Greek en, in + trope, change). Ludwig Boltzmann (1844-1906) considered entropy in terms of statistical mechanics. He described entropy (S) in terms of the number (Ω) of possible microstates (organizations of its molecular components) that could result in a system’s macrostate (temperature, pressure, volume, density, etc.). His formulation of entropy, and of the second law of thermodynamics (with the passage of time entropy can only increase) are:

where ln is the natural logarithm and kBis Boltzmann’s constant.

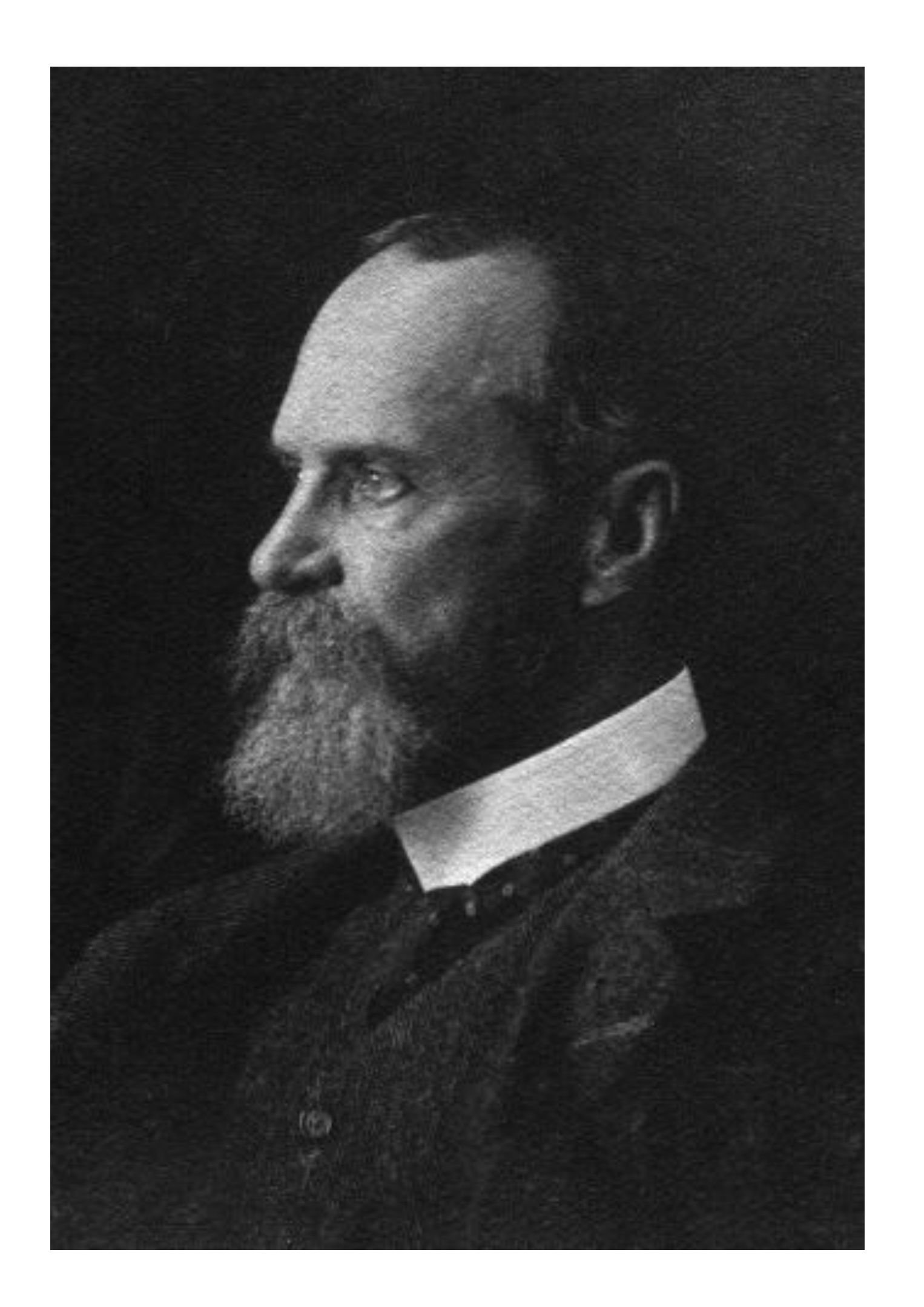

The concept of entropy led Arthur Eddington to propose the idea of “Time’s Arrow:”

Let us draw an arrow arbitrarily. If as we follow the arrow we find more and more of the random element in the state of the world, then the arrow is pointing towards the future; if the random element decreases the arrow points towards the past. That is the only distinction known to physics. This follows at once if our fundamental contention is admitted that the introduction of randomness is the only thing which cannot be undone. I shall use the phrase “time’s arrow” to express this one-way property of time which has no analogue in space. (Eddington, 1927, p 67.)

Unlike Zeno’s Arrow which is concerned with the nature of motion in time, Eddington’s arrow is concerned with the nature of time itself.

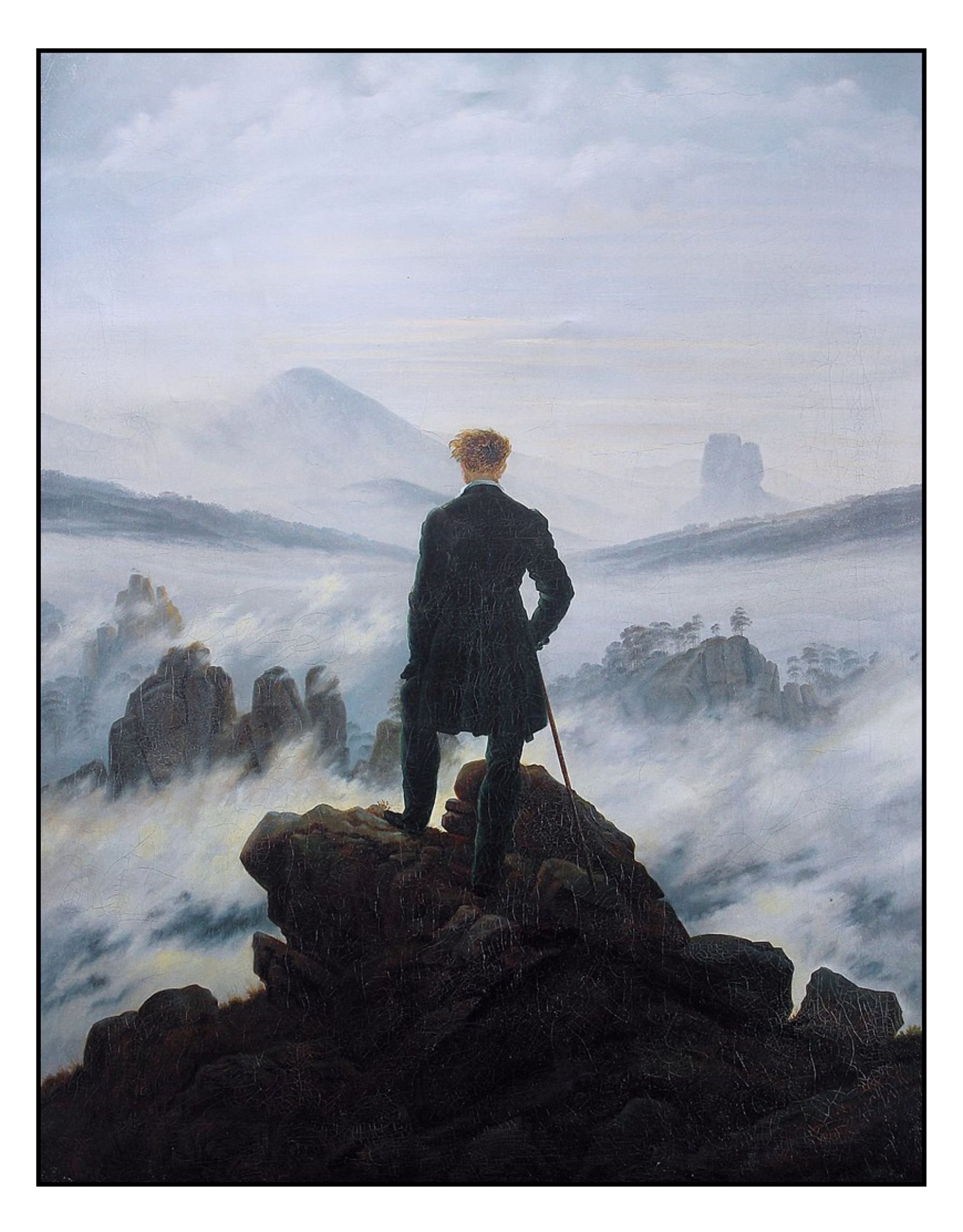

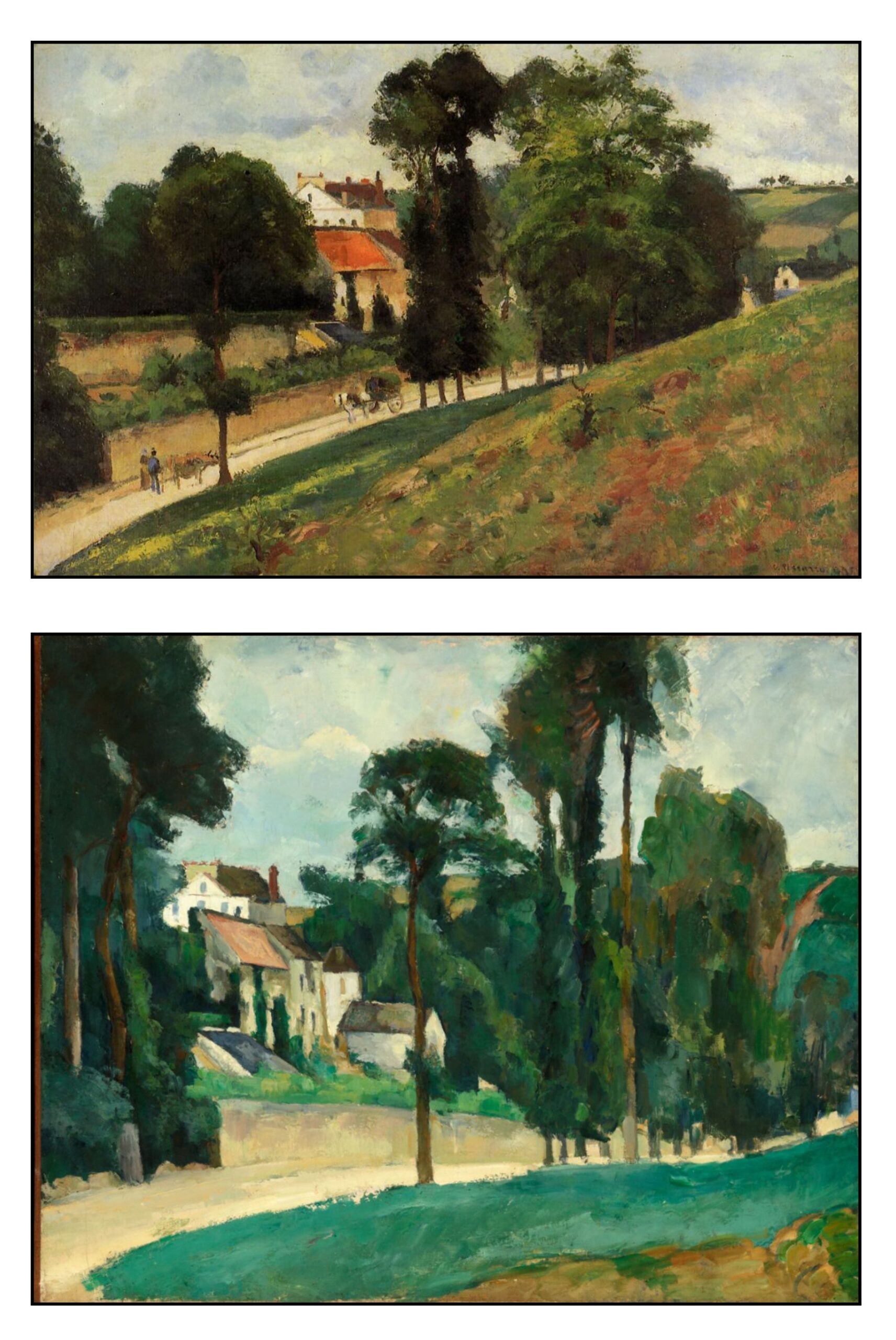

The Graveyard by the Sea

In 1922, Paul Valéry wrote a long poem Le Cimetière Marin about time and mortality. Its setting is a cemetery overlooking the Mediterranean Sea at Sète in Southern France:

At the poem’s climax, Valéry calls on Zeno.:

Zénon! Cruel Zénon! Zénon d’Êlée!

M’as-tu percé de cette flèche ailée

Qui vibre, vole, et qui ne vole pas!

Le son m’enfante et la flèche me tue!

Ah! le soleil . . . Quelle ombre de tortue

Pour l’âme, Achille immobile à grands pas!

;Zeno, Zeno, cruel philosopher Zeno,

Have you then pierced me with your feathered arrow

That hums and flies, yet does not fly! The sounding

Shaft gives me life, the arrow kills. Oh, sun! —

Oh, what a tortoise-shadow to outrun

My soul, Achilles’ giant stride left standing!

(translation by C. Day-Lewis, 1950)

Zeno, Zeno, the cruel, Elean Zeno!

You’ve truly fixed me with that feathered arrow

Which quivers as it flies and never moves!

The sound begets me and the arrow kills!

Ah, sun! . . . What a tortoise shadow for the soul,

Achilles motionless in his giant stride!

(translation of David Paul, 1971)

(I have included two translations, one by Day-Lewis which maintains the rhyme scheme and a more literal version by Paul.)

Valéry’s imagery is complex, it melds Time’s Arrow with Zeno’s paradoxes of the Arrow and of Achilles and the Tortoise. Time will proceed to death and disorder before we can ever attain eternity.

Valéry does not leave usstumbling unsuccessfully after the Tortoise. His poem ends with an invocation to live completely in the life we have no matter that it leads to death.

Le vent se lève! . . . Il faut tenter de vivre!

L’air immense ouvre et referme mon livre,

La vague en poudre ose jaillir des rocs!

Envolez-vous, pages tout éblouies!

Rompez, vagues! Rompez d’eaux réjouies

Ce toit tranquille où picoraient des focs!

The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!

The huge air opens and shuts my book: the wave

Dares to explode out of the rocks in reeking

Spray. Fly away, my sun-bewildered pages!

Break, waves! Break up with your rejoicing surges

This quiet roof where sails like doves were pecking.

(Day-Lewis)

The wind is rising! . . . We must try to live!

Hie immense air opens and shuts my book,

A wave dares burst in powder over the rocks.

Pages, whirl away in a dazzling riot!

And break, waves, rejoicing, break that quiet

Roof where foraging sails dipped their beaks!

(Paul)

The last line of the poem alludes to its opening where Valéry likened the boats sailing on the sea to doves moving on an immense roof. That quiet roof – the sea – represents the eternity that we live not long enough to understand.

Reference

Black, M. (1970). Achilles and the tortoise. In W. C. Salmon (Ed.). Zeno’s paradoxes. (pp. 67-81). Bobbs-Merrill.

Dowden, B. (accessed 2023) Zeno’s paradoxes. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Eddington, A. S. (1928) The nature of the physical world. Cambridge University Press.

Grünbaum, A. (1967). Modern science and Zeno’s paradoxes. Wesleyan University Press.

Harrington, J. (2015). Zeno’s paradoxes and the nature of change. In Time: A Philosophical

Introduction. (pp. 17–62). Bloomsbury Academic.

Huggett, N. (2018). Zeno’s Paradoxes. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

James, W. H. (1911). Some problems of philosophy: a beginning of an introduction to philosophy. Longmans, Green.

Markosian, N., Sullivan, M., & Emery, N. (2018). Time. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

McLaughlin, W. I. (1994). Resolving Zeno’s Paradoxes. Scientific American, 271(5), 84-89

Palmer, J. (2021). Zeno of Elea. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Reeder, P. (2015). Zeno’s arrow and the infinitesimal calculus. Synthese, 192(5), 1315–1335.

Rovelli, C. (translated by E. Segre & S. Carnell, 2018). The order of time. Riverhead Books.

Russell, B. (revised version, 1926). Our knowledge of the external world as a field for scientific method in philosophy. Allen and Unwin.

Sainsbury, R. M. (2009). Paradoxes (3rd edition). Cambridge University Press.

Salmon, W. C. (1970). Zeno’s paradoxes. Bobbs-Merrill.

Strobach, N. (2013). Zeno’s Paradoxes. In H. Dyke & A. Bardon (Eds) A Companion to the Philosophy of Time (pp. 30–46). John Wiley & Sons

Valéry, P. (translated by C. Day-Lewis, 1946). Le Cimetière marin / The graveyard by the sea. M. Secker & Warburg.

Valéry, P. (translated by D. Paul and edited by J. R. Lawler, 1971). Collected works of Paul Valery. Volume 1. Poems. Princeton University Press.