Belief and Heresy

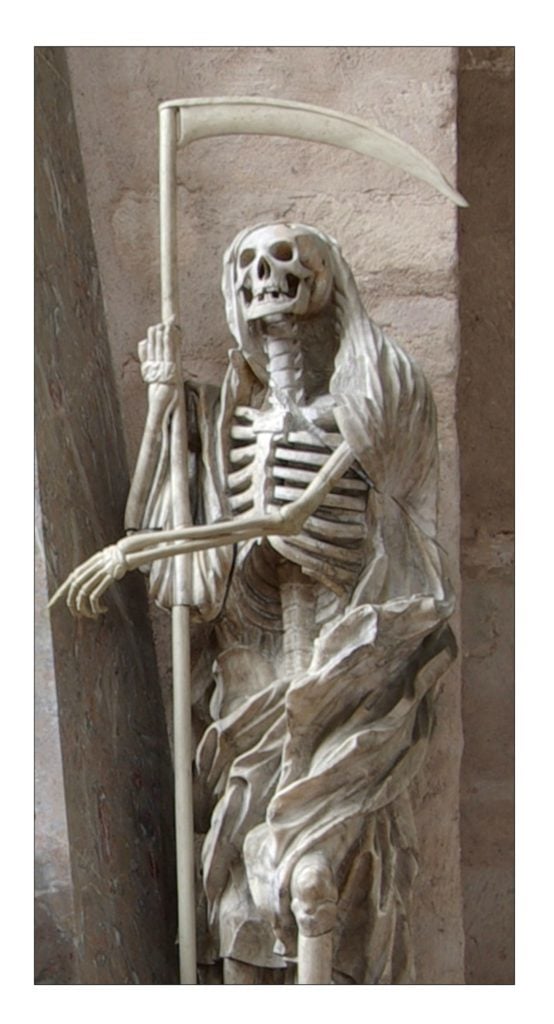

Religious belief differs from everyday belief. Since it cannot be tested or independently confirmed, religious belief must be accepted on faith. Religious belief generally starts with a few powerful and attractive ideas. For example: would it not be wonderful if we did not have to die? As time passes these foundational principles are elaborated and bolstered by other equally untestable beliefs to form a relatively coherent set of teachings. These “doctrines” can then organize communities of the faithful, govern the behavior of believers, and attract new converts. Some believers may choose to interpret the foundational ideas of a faith differently from the system of beliefs that are considered “orthodox” (Greek: ortho straight, correct + doxa, opinion). Beliefs that differ from the orthodox are termed heretical (Greek: hairesis, choice). Heresies are usually considered dangerous since they can easily disrupt the accepted doctrine and question the power of those who promote orthodoxy. Heresy occurs in the history of all the world’s religions (Henderson, 1988) This post limits itself to the early Christian beliefs and heresies about the nature of God, particularly those concerning the Trinity.

Belief and Belief-In

In philosophy and psychology belief is considered the “attitude” we take when we regard something as true (Schwitzgebel, 2021). Beliefs are for the most part unconscious. They come to consciousness when the belief requires action. Simple beliefs are typically expressed using a proposition: I believe that … Most would propose that there are degrees of belief. I am more certain (or confident) that the sun will come up tomorrow than that I shall win the lottery. The confidence I have in a belief comes from how much supporting evidence I have amassed for it. When fully justified, my belief can be considered “knowledge.”

When belief is used with a direct object, it typically means having confidence in the truth or accuracy of someone or something. Thus, I can believe the witness when she describes what happened to her. Or I can believe the newspaper’s account of the event.

Saying that I “believe in” something has various meanings (Price, 1965; Williams, 1992; MacIntosh, 1994). In the simplest case, believing in something just means believing that it exists. When I say that I believe in fairies, I am just asserting that fairies exist. Typically, such statements have little in the way of justification. If the belief were justified, one would not need to state it in this way.

“Believe-in” often implies a positive evaluation. When I state that I believe in my doctor, I am claiming that she not only exists but that she is good at what she does. This evaluative usage extends to more abstract ideas: when assert that I believe in democracy I mean that I consider it better than other types of government.

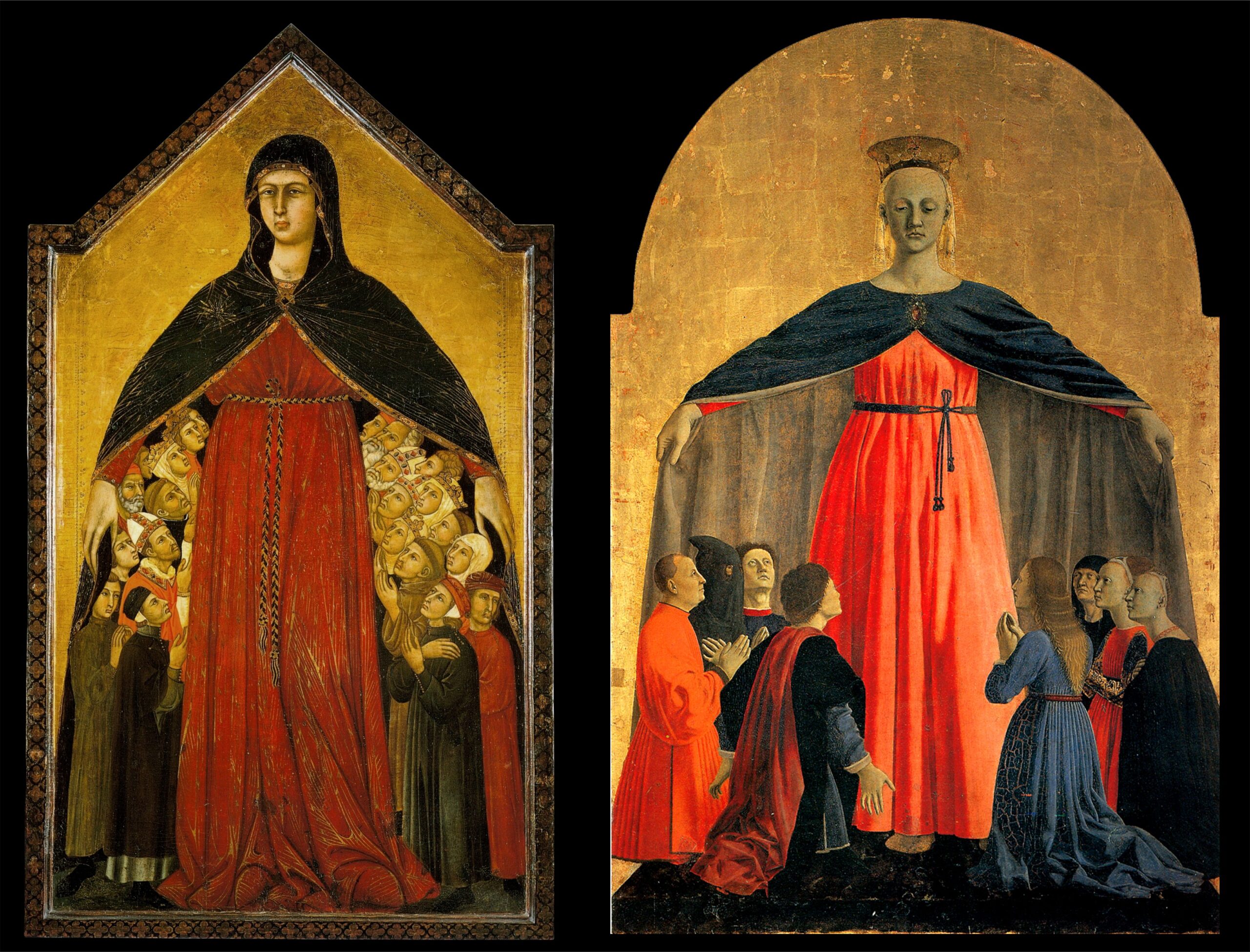

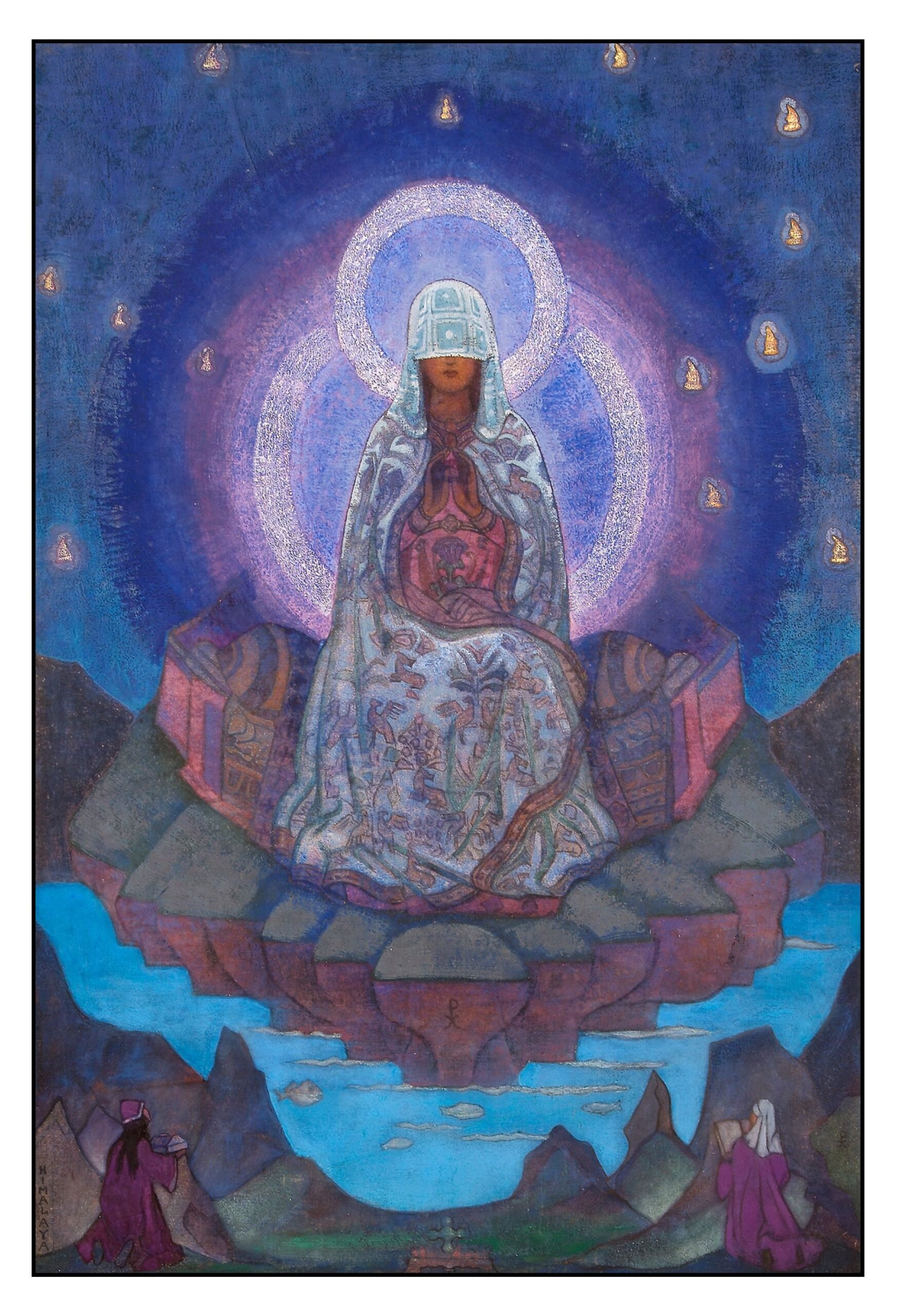

In the religious sense, the phrase “believe in” includes beliefs in both the existence and the goodness of the object of belief, but also requires belief in a wealth of associated ideas (Luhrman, 2018). One of the foundational ideas of Christianity is expressed in Christ’s comments to Martha just before raising her brother Lazarus from the dead.

I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live:

And whosoever liveth and believeth in me shall never die. (John 11: 25-26)

Simply asserting that Christ existed and that he was a force for good is clearly not sufficient for the requirement that a person “believe in” Christ. One must also believe that he is divine, that he died so that those who believe in him do not have to die, that he was resurrected from death, and that he lives forever. Challenging requirements for one of a skeptical disposition. Such beliefs are not easy. However, the reward is invaluable: eternal life.

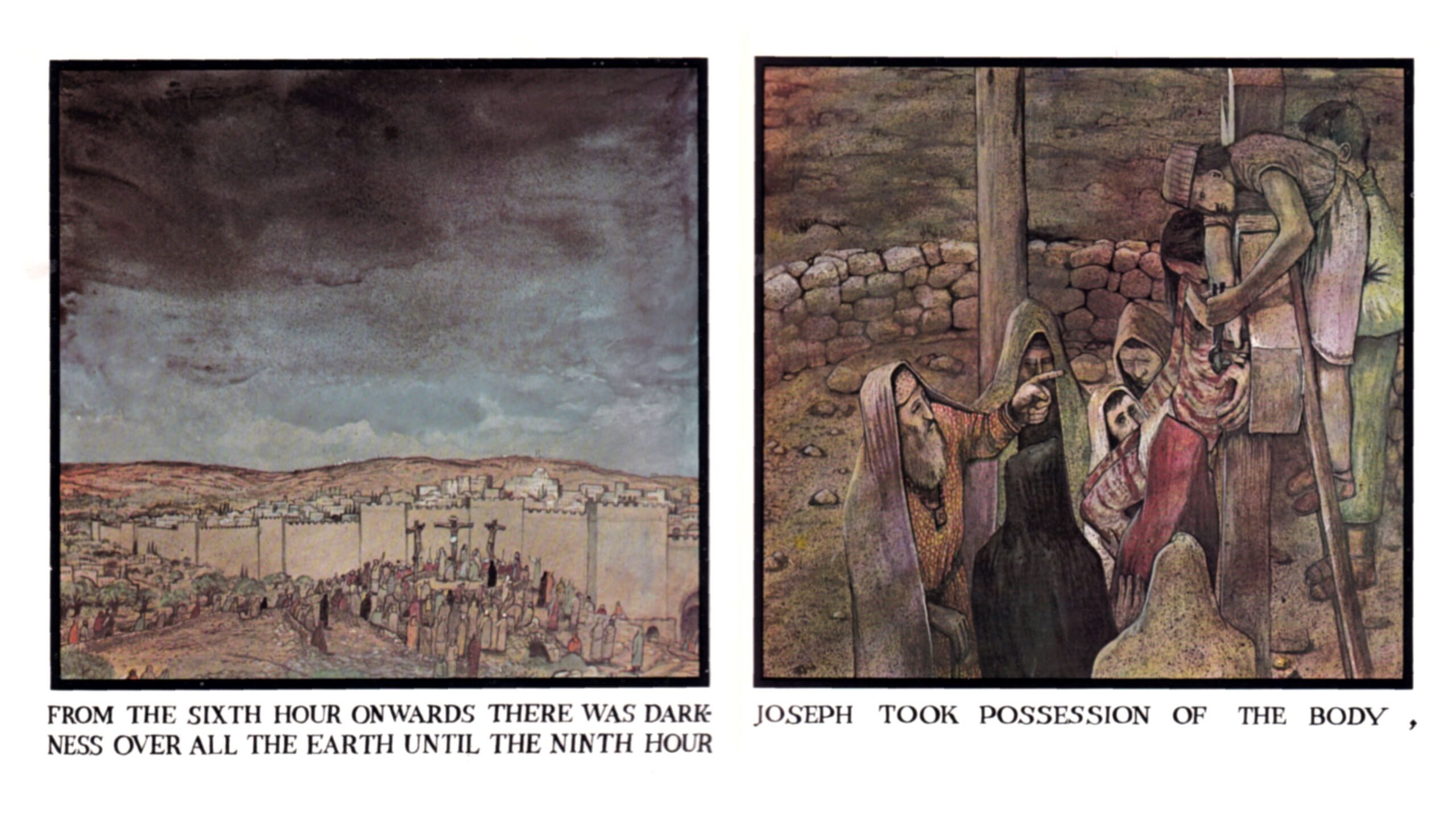

A Life of Jesus

For many years scholars have sought to determine which of the episodes in the life of Jesus reported in the gospels happened, and which were invented after the fact. This search for the “historical Jesus” (e.g. Schweitzer, 1910; Crossan, 1991; Meier, 1991; Wilson, 1992; Robinson, 2011) is controversial and highly subjective.

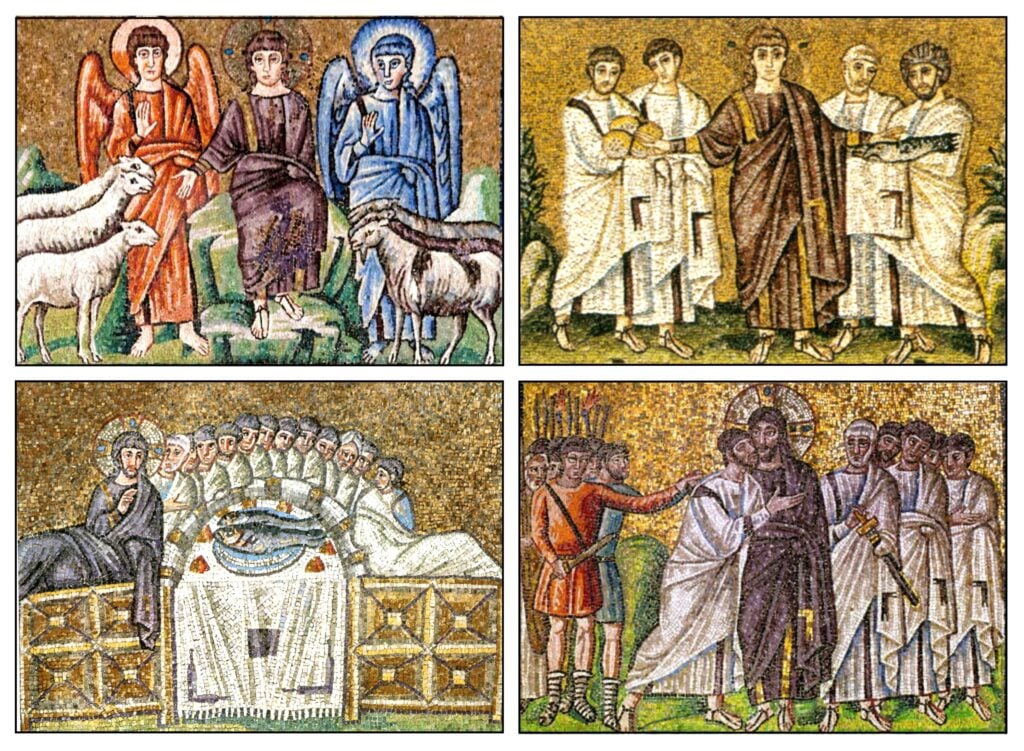

Jesus was a Galilean. He was likely born and grew up in Nazareth. There is no historical evidence for a Roman census, and the story of Bethlehem was probably invented to link the birth of Jesus to the line of David. Jesus likely interacted with John the Baptist, whose life and execution are noted in non-scriptural histories.

Jesus then became a preacher. He attracted a small group of disciples and large crowds of followers. He championed the poor and the dispossessed. He proposed that all the commandments could be subsumed in the simple instructions to love God and to love one’s neighbor. He promoted the idea of forgiveness instead of vengeance.

He considered himself a simple human being – a “Son of Man;” yet, he also felt that he had been specially chosen by God to teach or lead his people – a “Son of God.” The Greek word christos (Christ) means the “appointed one,” and is equivalent to the Hebrew word masiah (Messiah). Jesus preached the coming of a “Kingdom of Heaven” but it is not clear what this meant: perhaps an independent Jewish state, or perhaps simply a community of people working together for the common good.

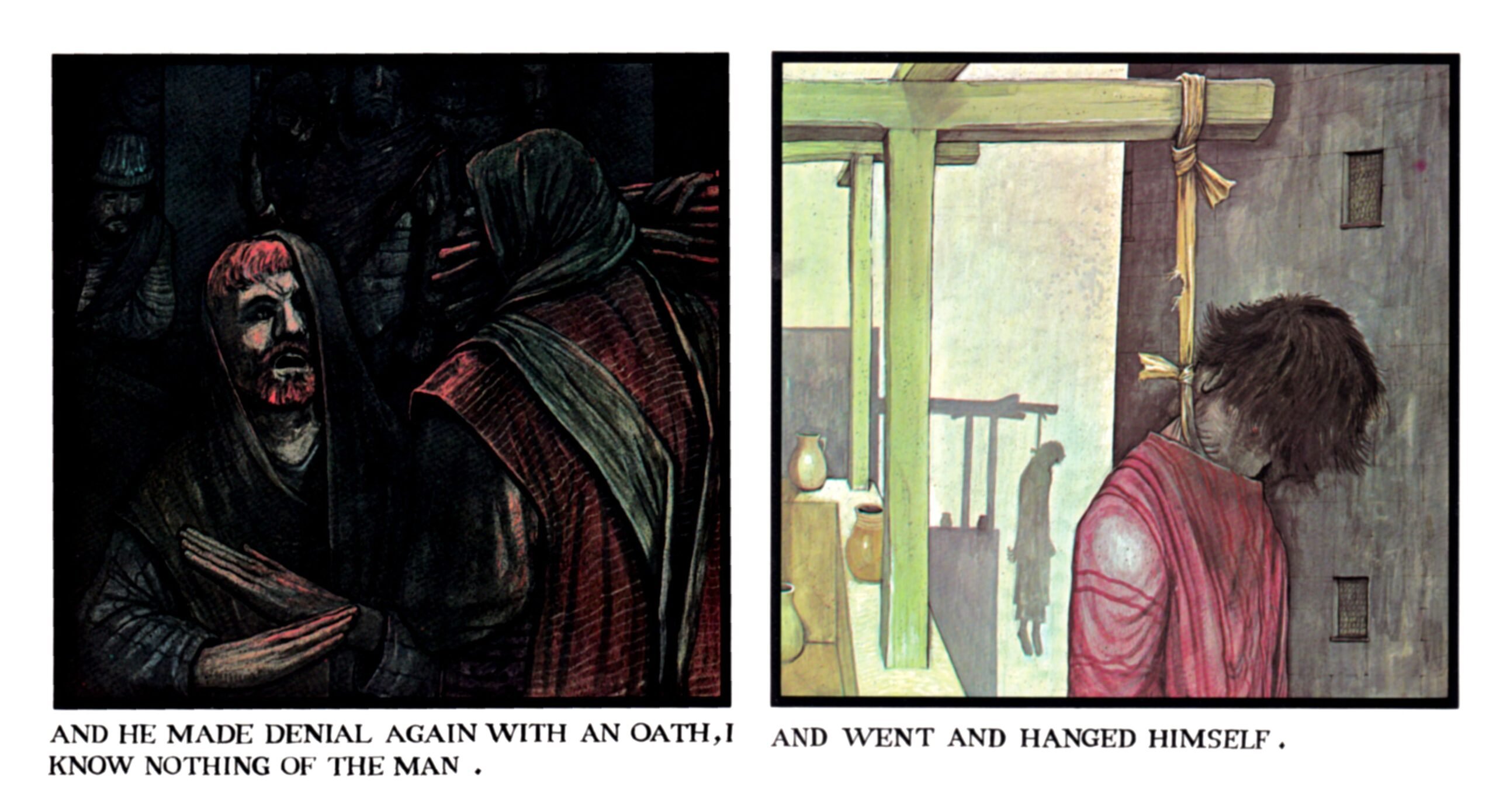

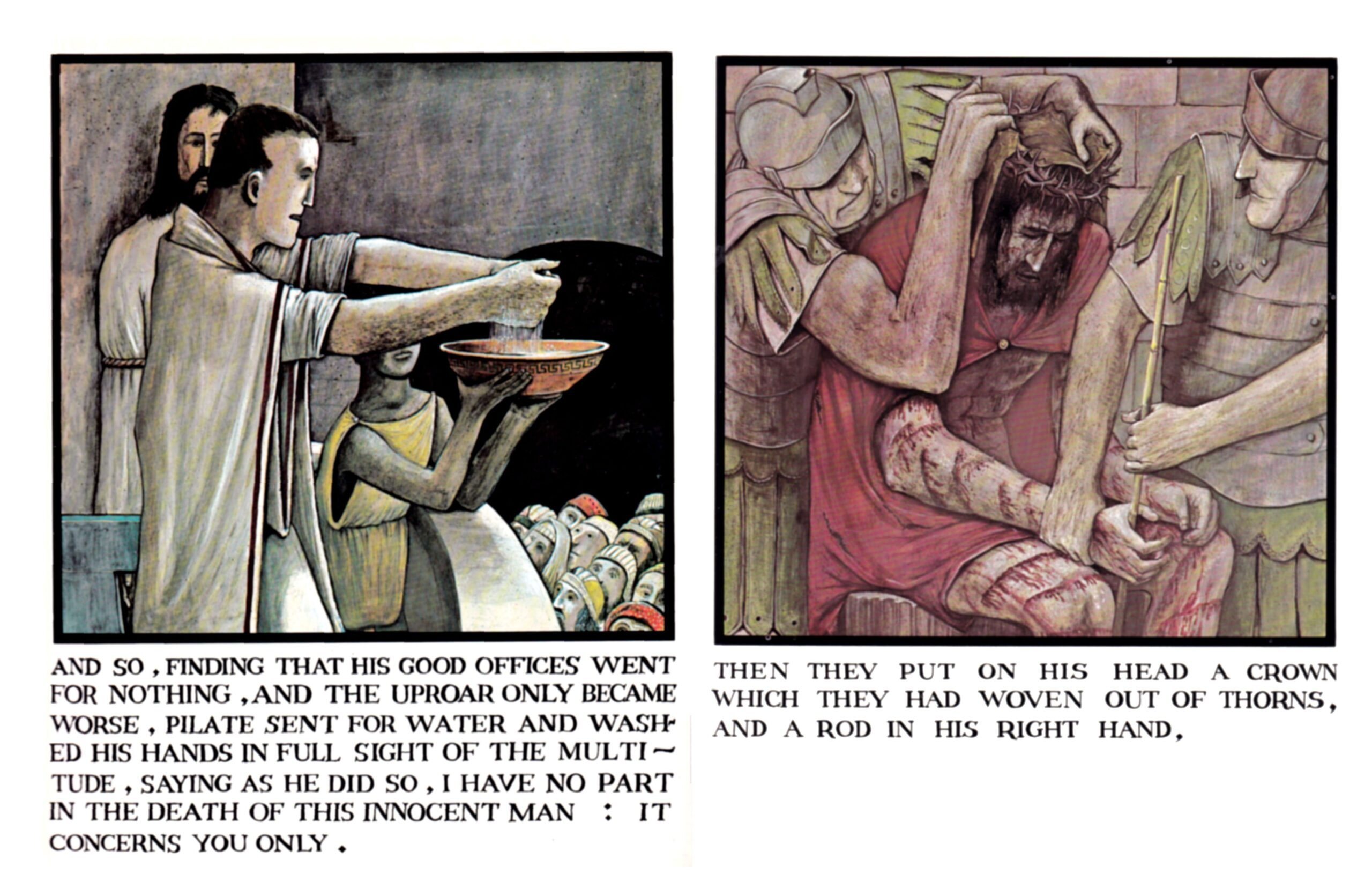

His simplification of the commandments and his criticism of the temple antagonized the priests; his call for a new Kingdom of Heaven alarmed the Roman powers that occupied the land. He was tried by both the Jews and the Romans. He was found guilty of blasphemy and of sedition. He was crucified and died upon a cross. His disciples were devastated.

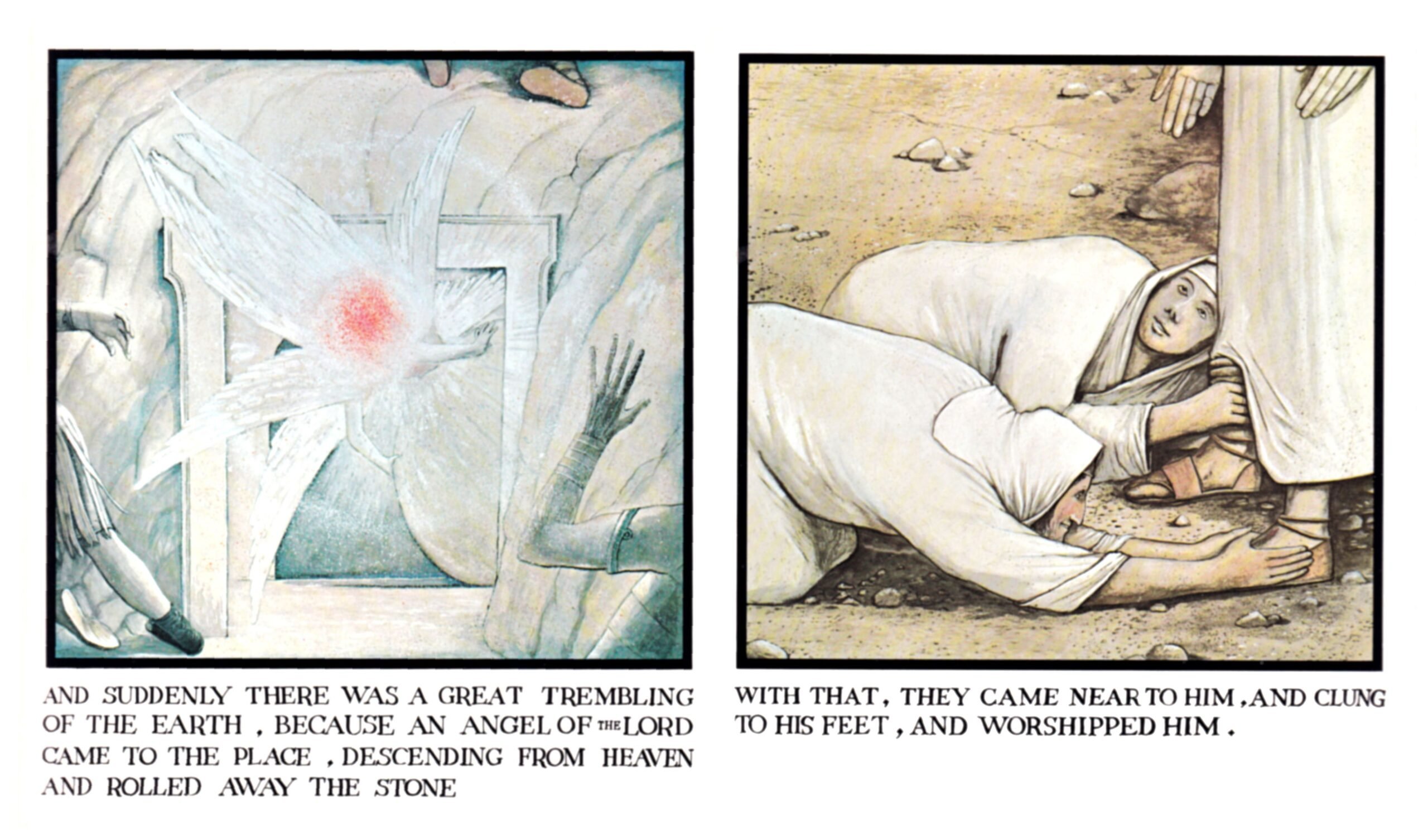

Jesus was likely buried in the tomb of one of his followers. Nothing that happened after this is clear. Perhaps the tomb was found empty. This could then have triggered the hope that Jesus had been resurrected.

The preceding paragraphs have presented my personal idea of the historical Jesus. The following is from Ehrman’s 2012 book Did Jesus exist?

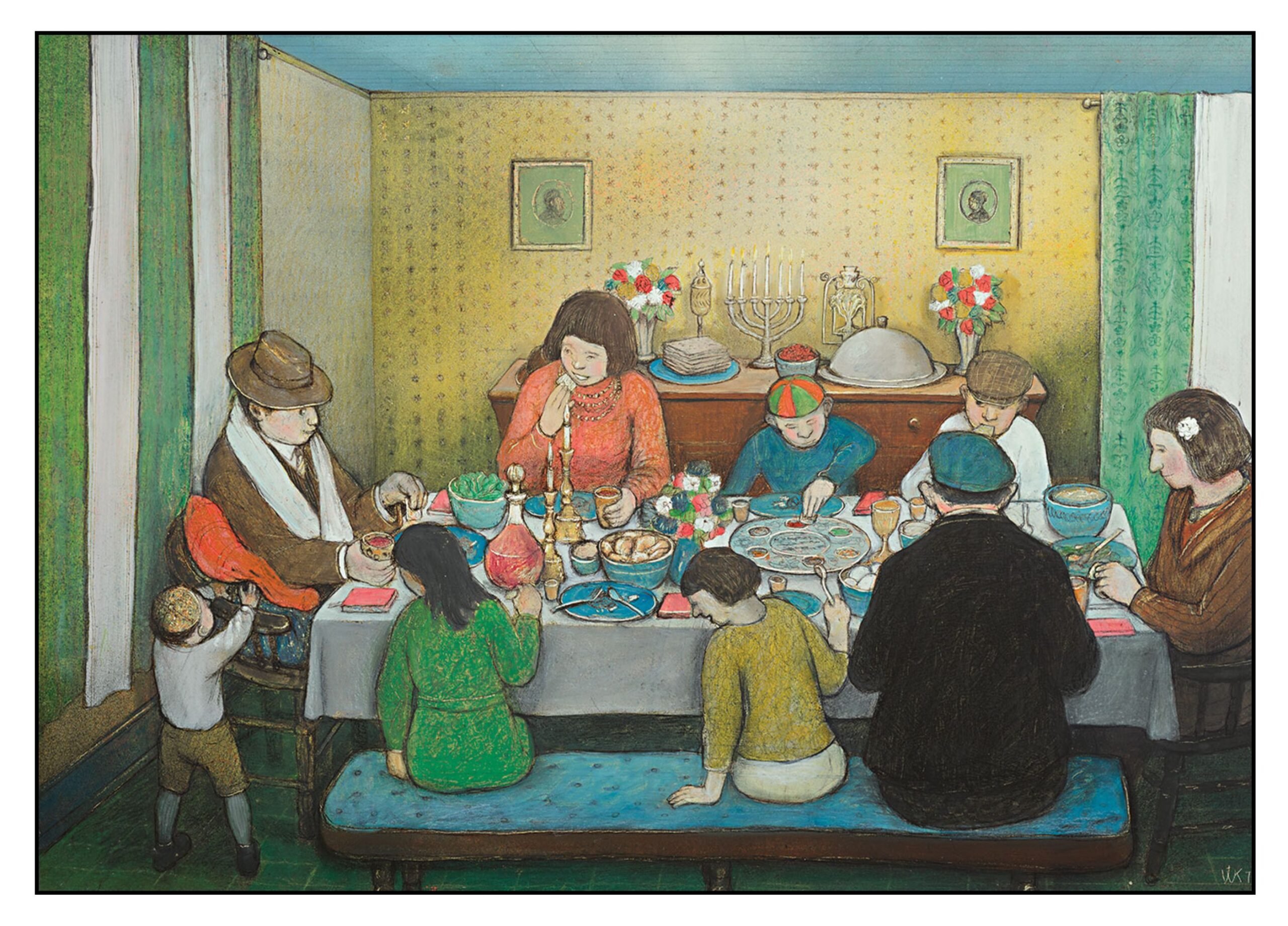

Jesus was a Jew who came from northern Palestine (Nazareth) and lived as an adult in the 20s of the Common Era. He was at one point of his life a follower of John the Baptist and then became a preacher and teacher to the Jews in the rural areas of Galilee. He preached a message about the “kingdom of God” and did so by telling parables. He gathered disciples and developed a reputation for being able to heal the sick and cast out demons. At the very end of his life, probably around 30 CE, he made a trip to Jerusalem during a Passover feast and roused opposition among the local Jewish leaders, who arranged to have him put on trial before Pontius Pilate, who ordered him to be crucified for calling himself the king of the Jews. (p 269)

Jesus as God

The empty tomb could have easily led to ideas that Jesus had risen from the dead. Any such resurrection would have entailed supernatural intervention. Jesus had claimed to be the Messiah. Could he perhaps have been even more special? Perhaps Jesus was himself divine. From such thinking came John’s idea of Jesus as the Word (Greek, logos – the order underlying the universe):

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

The same was in the beginning with God.

All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made.

In him was life; and the life was the light of men. (John 1:1-4)

Yet Jesus had been so terribly human in his suffering. From such thoughts came the idea of the incarnation. Though divine, Jesus was born as a human being:

And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, (and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father,) full of grace and truth. (John 1: 14)

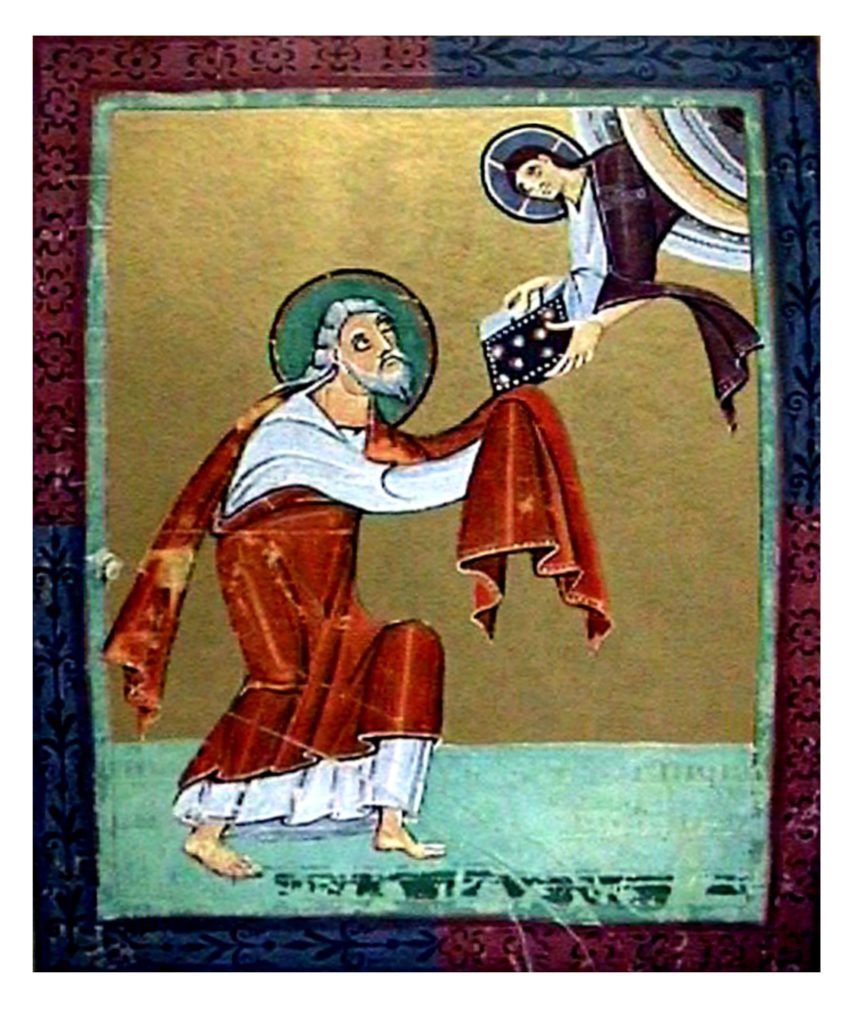

The first person to recognize the divinity of Jesus was John the Baptist, who noted that as Jesus was being baptized

I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it abode upon him. (John 1:32)

From these ideas of Father, Son and Spirit came the idea of a triune God, and a new religion based on the resurrection of Christ, who died to save us from our sins.

After the crucifixion the disciples saw the resurrected Jesus upon on a mountain in Galilee:

And Jesus came and spake unto them, saying, All power is given unto me in heaven and in earth.

Go ye therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost:

Teaching them to observe all things whatsoever I have commanded you: and, lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world. Amen. (Matthew, 28: 18-20).

This is the only acknowledgement of the Trinity in the gospels. Translations more modern than the King James Version use the name “Holy Spirit” for the third member of the Trinity. These verses may be a later addition to the original gospel (see discussion by Schaberg, 1980; Funk et al, 1996; Thellman, 2019). However, the same baptismal formula is used in the Didache (Teachings of the Apostles: O’Loughlin, 2010; Jefford, 2013), which was written soon after Matthew’s gospel (now dated to about 80 CE). Christians were clearly aware of the Trinity before the end of the 1st Century CE.

Trinitarian Doctrines

Although it occasionally mentions the Trinity, the New Testament does not describe the nature of a three-part God (Wainwright, 2011; Young, 2006). Rather, the doctrine of the Trinity was proposed by theologians during the second and third Centuries CE (Evans, 2003; Dünzl, 2007; Hillar, 2012; Phan, 2011; Tuggy 2020b). Despite twenty centuries of study, it remains an idea impossible to understand: a stumbling block to belief. Buzzard and Hunting (1999) called it “Christianity’s self-inflicted wound.”

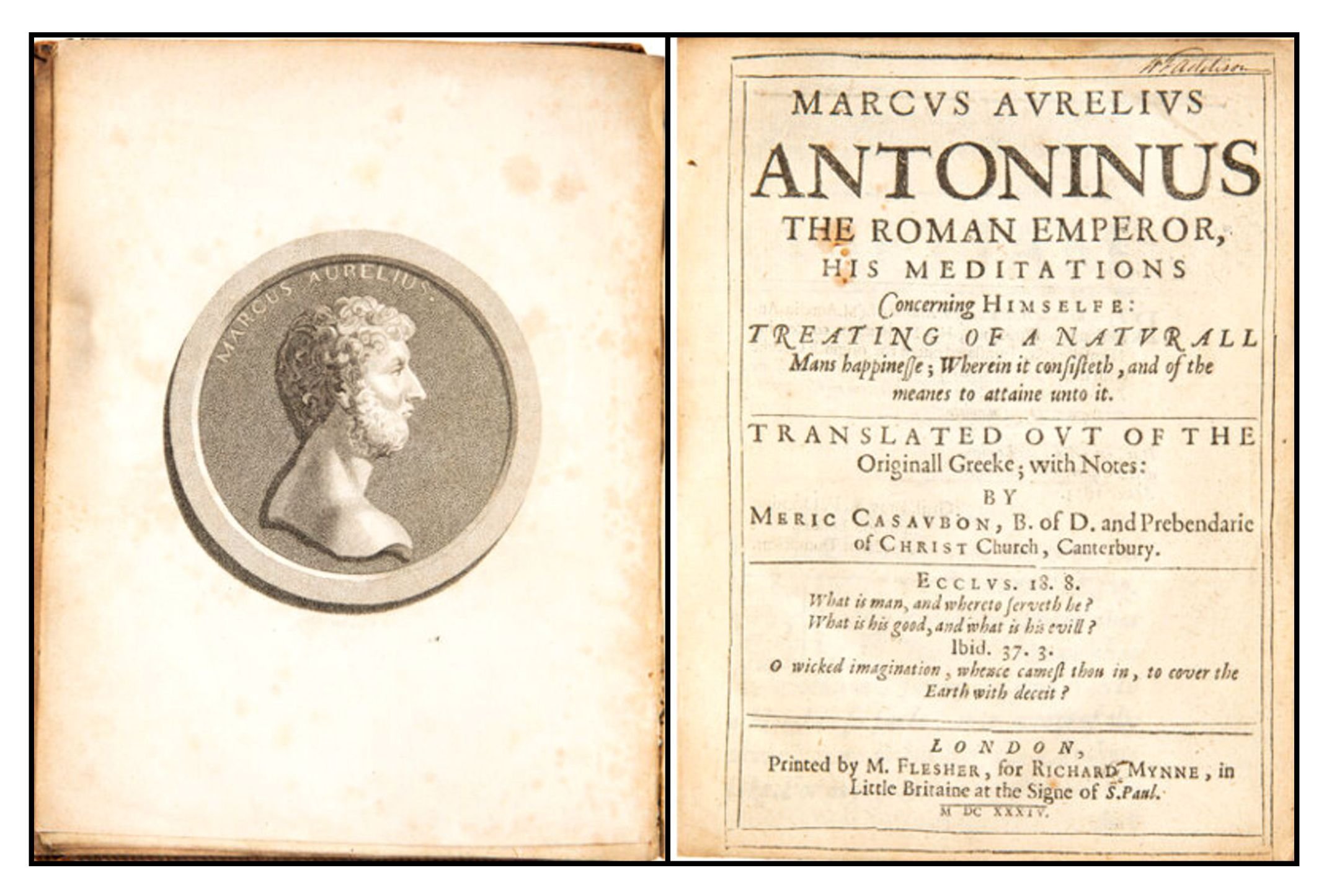

Justin Martyr (100-165 CE), an early Christian convert from Palestine, taught in Rome during the reign of Marcus Aurelius, and was beheaded for his beliefs. He was the first to propose that God the Father and God the Son were of the same substance (Greek: homoousios). However, this idea made no claim as to whether God the Father preceded the Son or were they both coequal and coeternal.

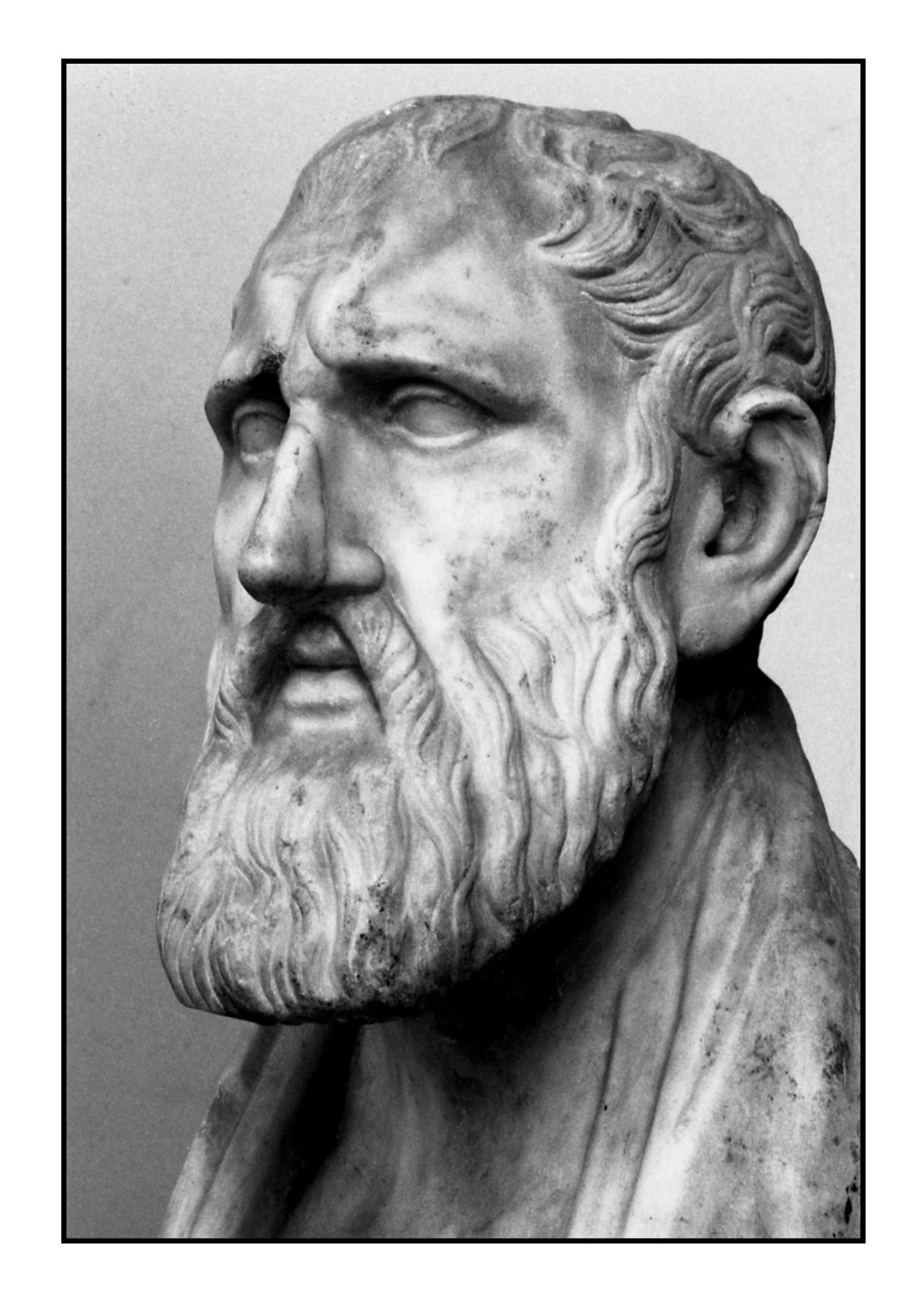

Sabellius (who taught around 200 CE) was North African Christian who came to Rome to preach the gospel. His ideas are only known from those who condemned them as heretical. He appears to have believed that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were but three “aspects” or “modes” of the one God. He purportedly used an analogy to the Sun, which has a circular form (Father), gives forth light (Son), and provides warmth (Spirit).

Tertullian (155-220 CE) from Carthage was the first Christian theologian to use the word “trinity” (Latin trinitas) to describe Godhead. He argued against Christians like Sabellius who proposed that there was only one God – the monarchians (Greek mono, one + arkhia, rule). Tertullian claimed that God is three separate persons each of the same substance: three entities with one essence.

This concept of the Trinity could not easily explain the nature Christ – how could he be human if his essence was divine? This controversy persists to this day, the Western churches considering Christ to be one person with two natures (diaphysitism), and the Eastern churches believing Christ to have only one nature that somehow combines both the human and the divine (miaphysitism).

Tertullian’s version of the Trinity also did not clarify whether all three persons had existed for ever. Arius (256-336 CE), a charismatic Libyan preacher, taught that God was composed of three persons but believed the Father created both the Son and the Spirit when he created the universe. The Father alone was infinite, eternal, and almighty. Before the creation only the Father existed. Arius was vigorously opposed by Athanasius (298-373 CE), the bishop of Alexandria, who taught that all three persons of the Trinity were coequal and coeternal.

These theologians vehemently argued that those who disagreed with them should be condemned as heretics and excommunicated from the Church. Many early Christian thinkers were far more concerned with the nature of a God they could not understand than with the moral teachings of Christ. Compassion and forgiveness were not in their nature.

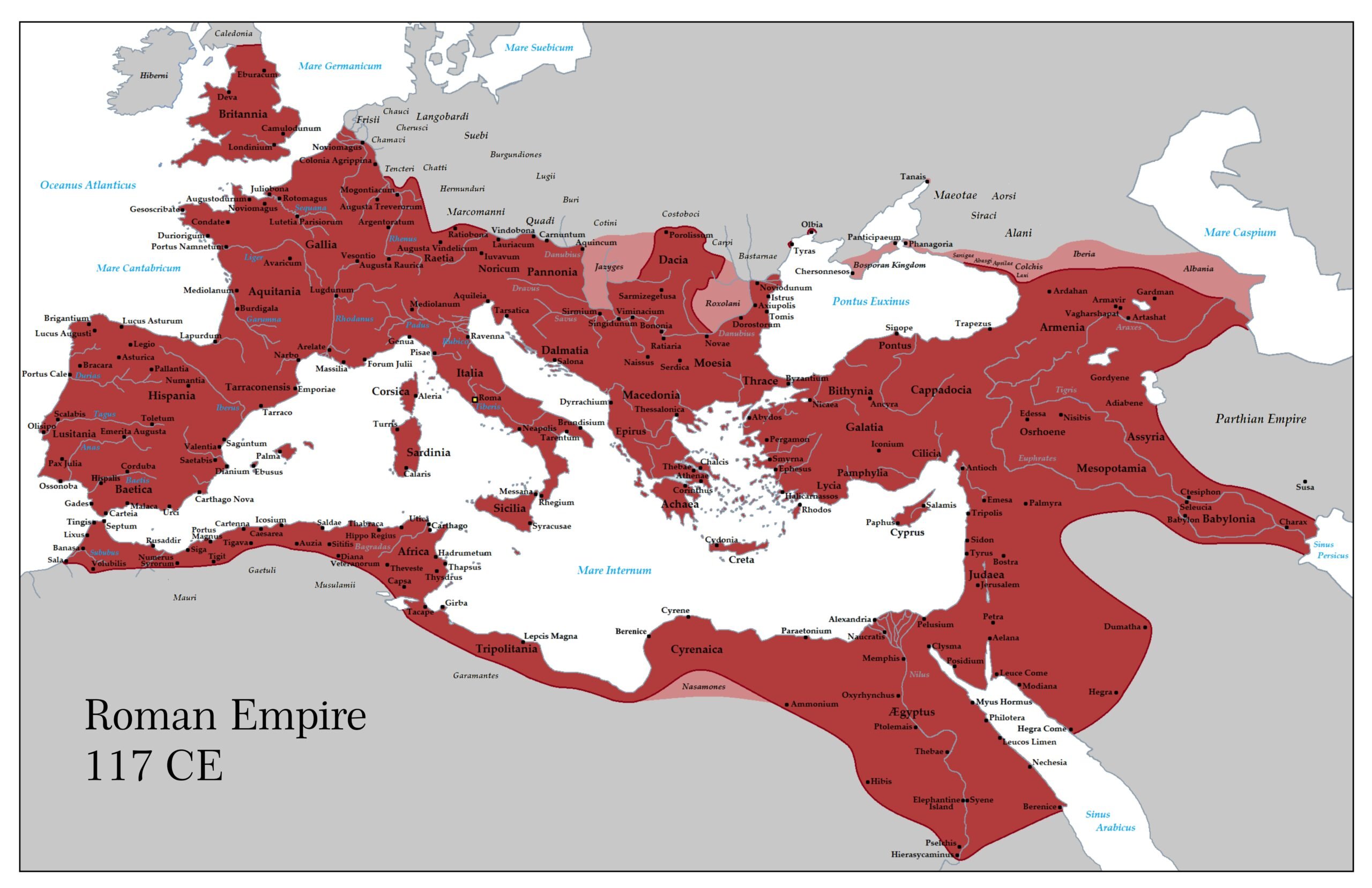

Constantine

At the age of 34 years, Constantine (272-337 CE) was initially acclaimed Roman Emperor after the death of his father Constantius in 306 CE. However, the empire was then governed by 5 co-rulers, all of whom desired to be the sole emperor. Over the next 18 years, these co-rulers battled for supremacy.

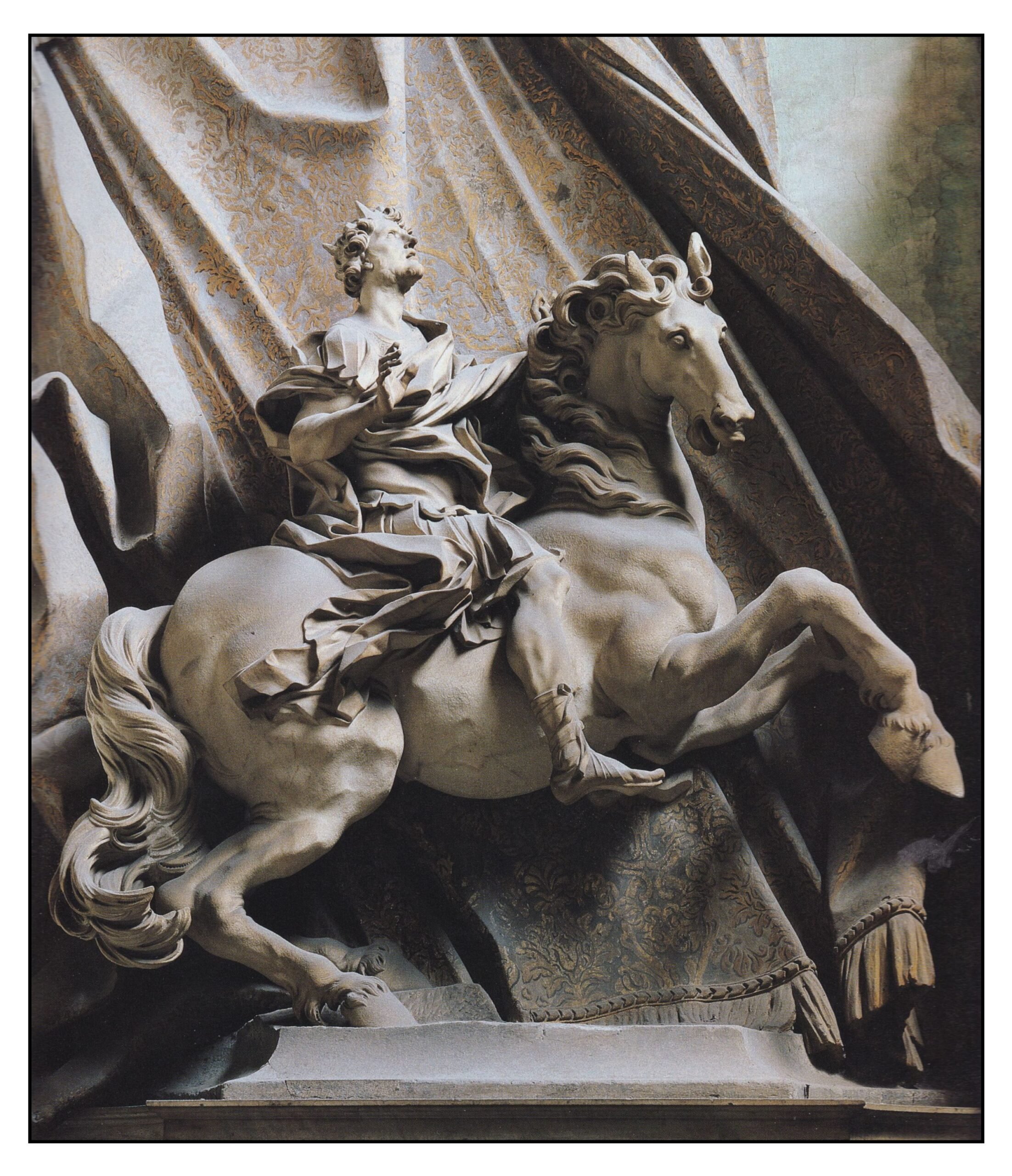

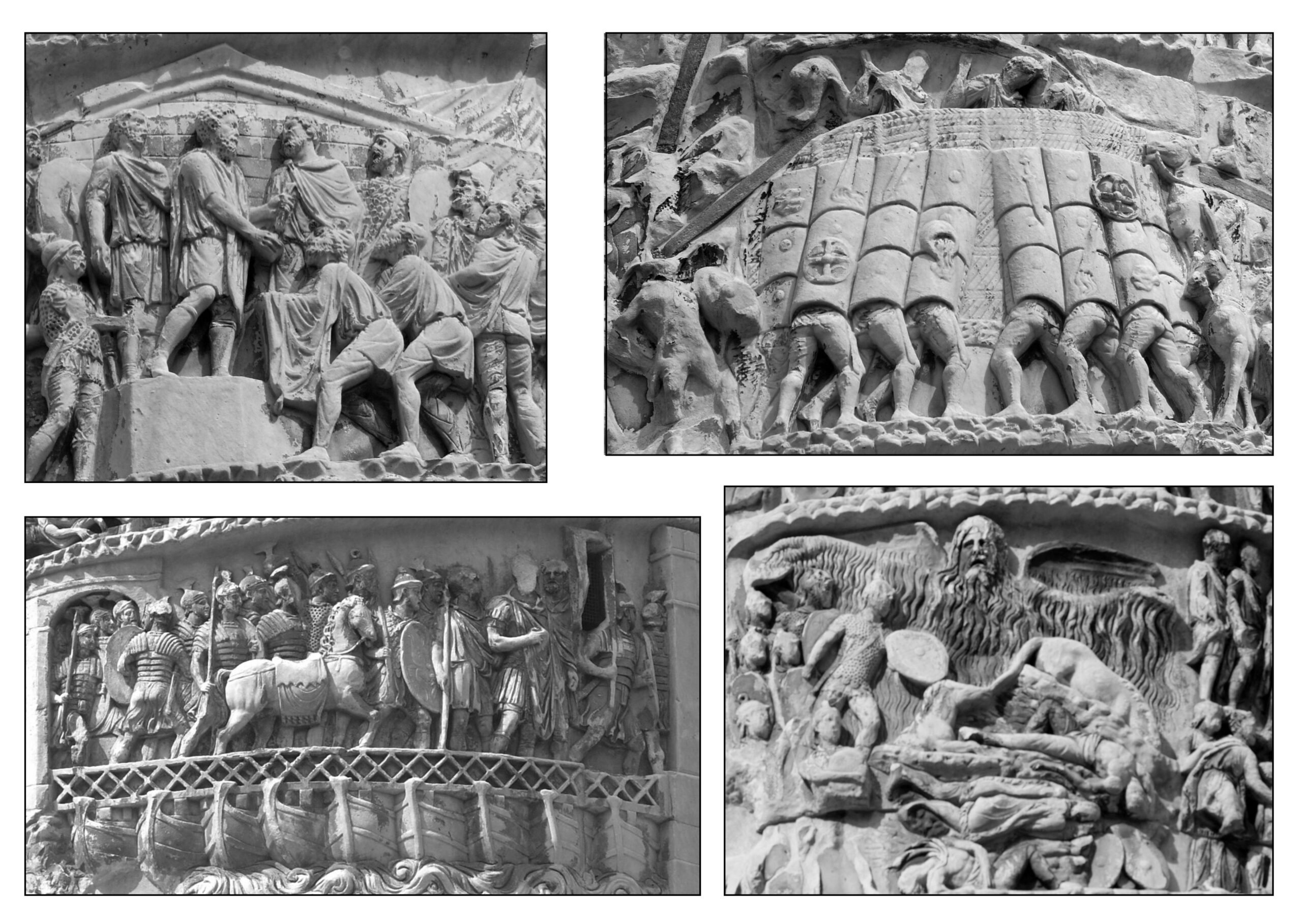

In the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312 CE, Maxentius, who had just proclaimed himself emperor, attempted to prevent Constantine’s entry into Rome. Just before the battle, Constantine saw in the sky a vision of a cross and the words En touto nika (Greek: With this sign you shall conquer). He therefore used as his military standard (Latin, labarum) the Chi-Rho symbol (a combinations of the first two letters of Christ’s name in Greek χ chi and ρ rho). Illustrated on the right is a 4th Century Roman sculpture with the Chi-rho symbol depicting the resurrection of Christ leaving the Roman soldiers to guard an empty tomb. Constantine was victorious. Thenceforth, Christianity was the religion of his army. Illustrated below is Bernini’s sculptural representation Constantine’s vision:

Ultimately, Constantine become sole emperor in 324 CE. He established his imperial capital at Constantinople, and made Christianity the imperial religion. History is not clear about Constantine’s personal relationship to Christianity. His mother Helena may have been a Christian when she married his father Constantius, and may have influenced her son’s thinking. She certainly was a fervent believer at the time that Constantine became emperor. From 326 to 328 CE, she made a pilgrimage to Palestine. Legend has it that she discovered in Jerusalem the cross on which Jesus had been crucified.

Constantine was not baptized until just before his death in 337 CE. He may have delayed because of personal doubts about the Christian religion, or he may have wished to absolve himself of as much sin as possible before dying. Constantine was baptized by Eusebius (Greek: pious) of Nicomedia, a priest who followed the teachings of Arius. By then, however, the emperor had promoted an orthodoxy that therefore made him a heretic.

The Nicene Creed

After becoming sole emperor, Constantine quickly realized that, if he wished to unify the empire through one religion, he would have to bring together the many feuding factions of Christianity. In 325 CE, he therefore convened the First Ecumenical (Greek: “concerning the whole inhabited earth”) Council at Nicaea a few miles south of Constantinople (in the modern city of Iznik). Theologians from all the reaches of the empire gathered to decide what it meant to be a Christian. They produced a statement of faith that became known as the Nicene Creed:

We believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of all things, visible and invisible. And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Son of God, begotten of the Father, only begotten, that is, of the substance of the Father; God of God; Light of light; very God of very God; begotten, not made; being of one substance with the Father; by whom all things were made, both things in heaven and things in earth; who for us men and for our salvation came down, and was incarnate, and was made man; who suffered, and rose again the third day; and ascended into heaven; and shall come again to judge the quick and the dead. And in the Holy Ghost, etc. (Plaff, 1885)

The “etc” likely means some formula known to all, such as

. . . in one baptism of repentance for the remission of sins, and in one Holy Catholic Church; and in the resurrection of the flesh; and in eternal life

Appended to the creed was a statement specifically condemning the ideas of Arius:

And those who say There was a time when He was not, or that Before He was begotten He was not, or that He was made out of nothing; or who say that The Son of God is of any other substance, or that He is changeable or unstable,—these the Catholic and Apostolic Church anathematizes.

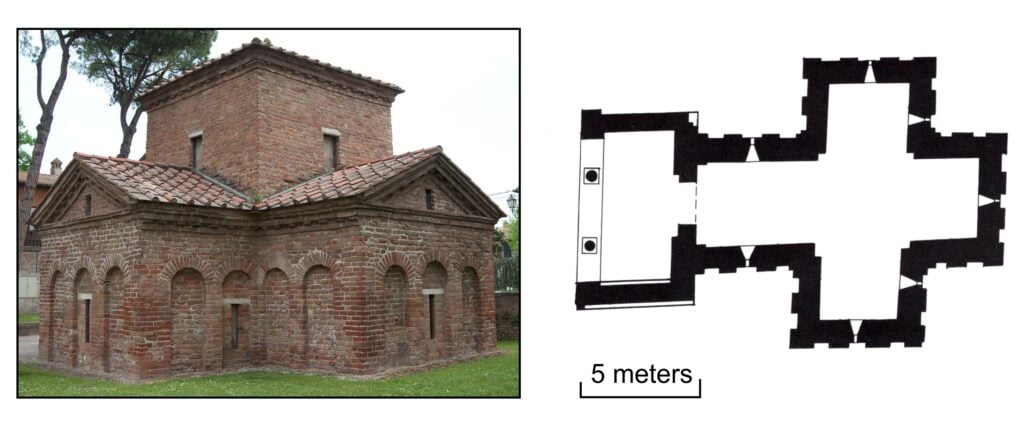

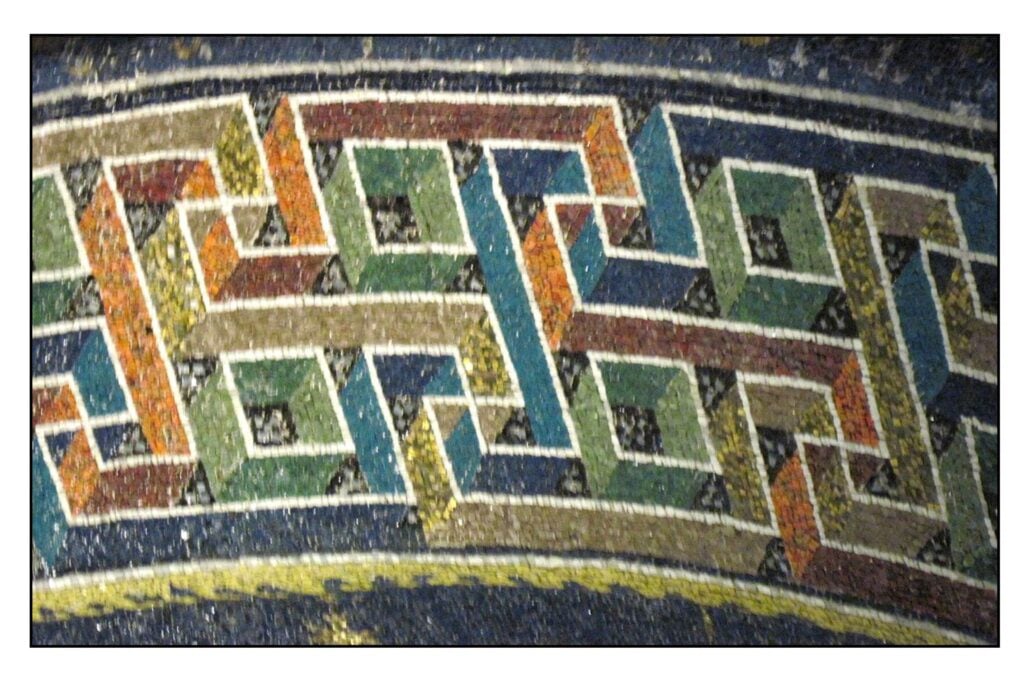

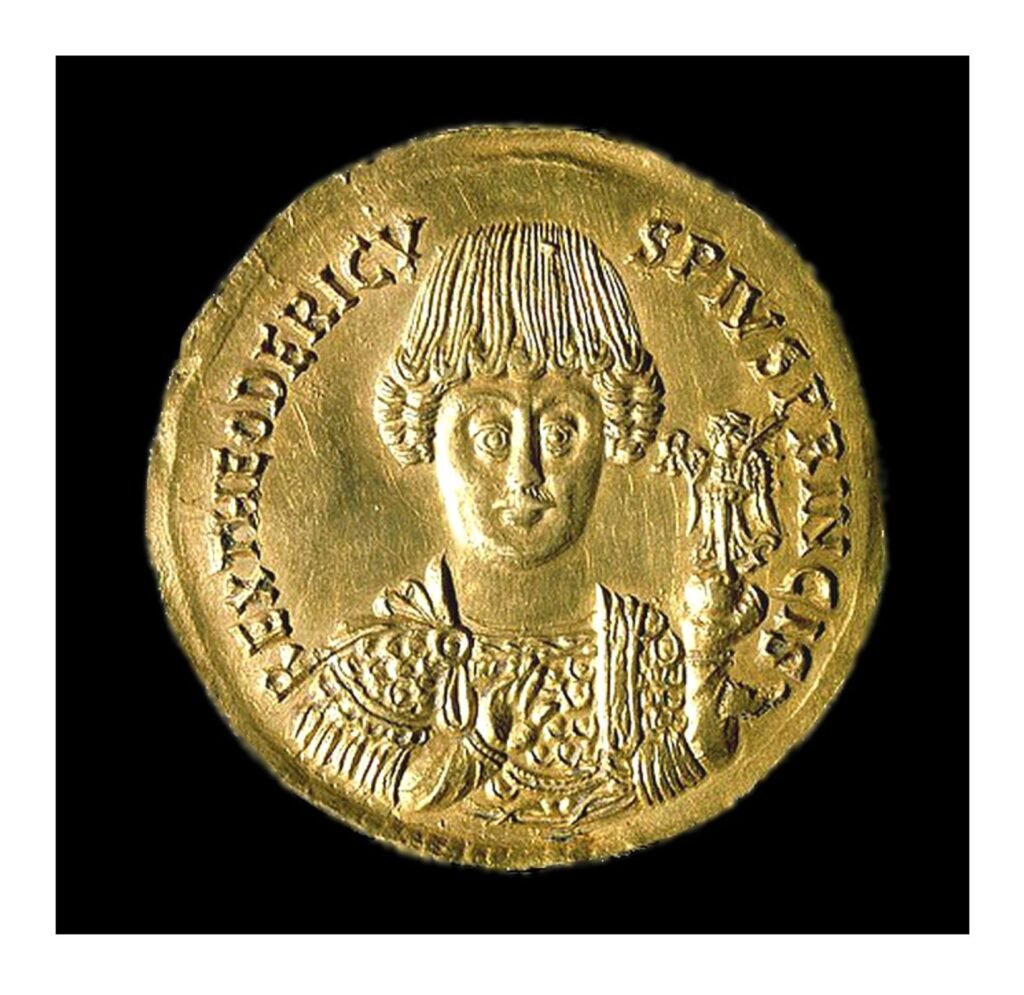

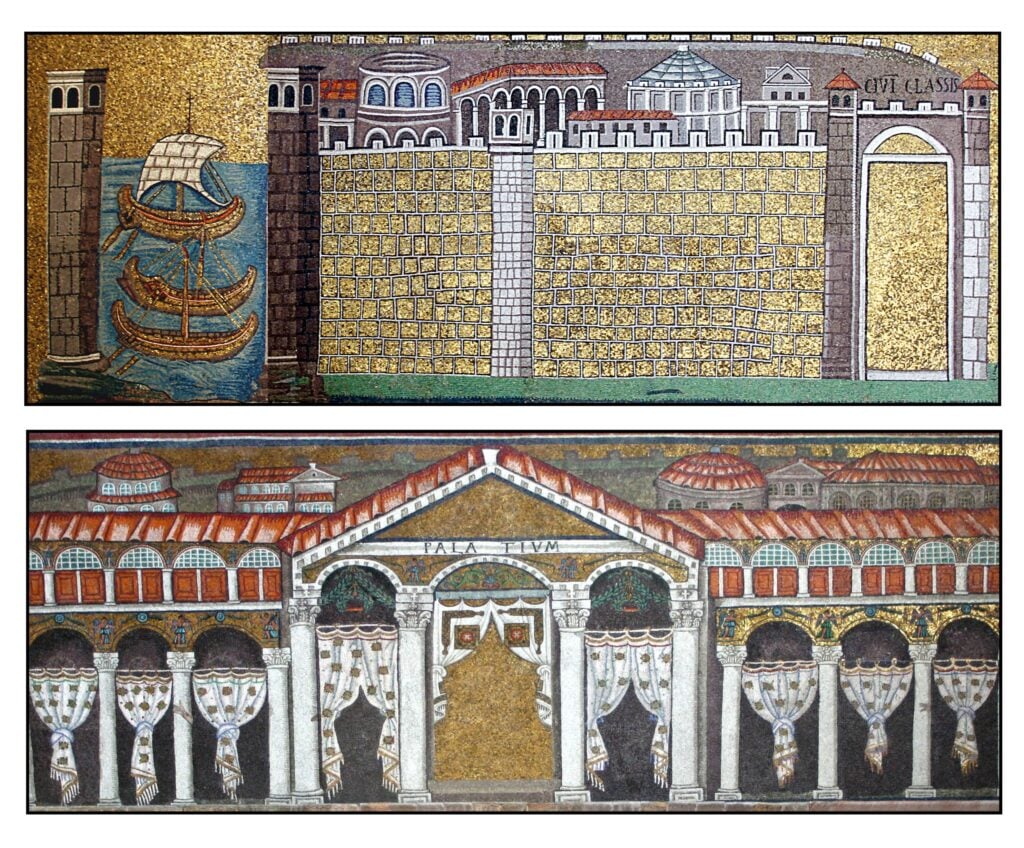

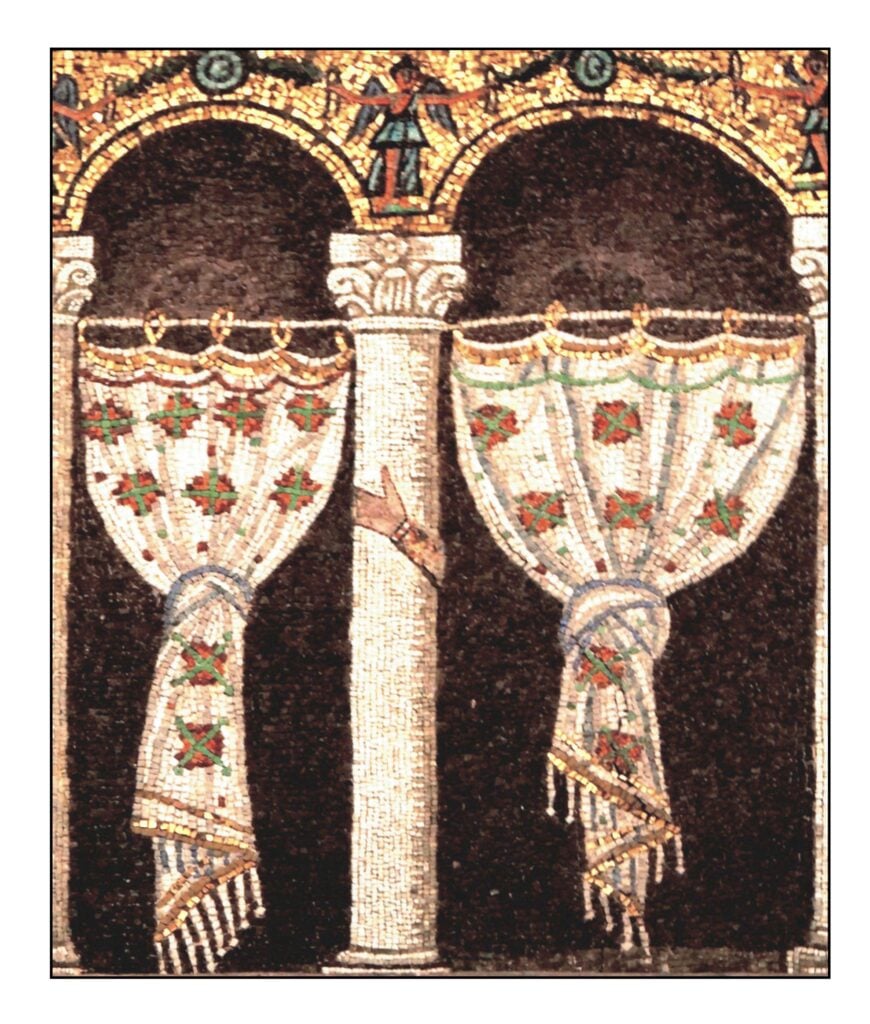

The Nicene Creed did not unify the Christian believers. Those that believed in Arius’ concept of the Trinity were formally damned as heretics. However, by that time Arianism had become the version of Christianity accepted through much of Northern Europe, and these ideas soon came to Italy with the barbarian invasions. Theodoric the Great, the Arian King of the Ostrogoths, built the great church now called the Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna in 504 CE. Mosaics showing the king and his court were later replaced with images of curtains, as Rome later re-exerted the orthodox views of the Trinity. However, the hands of the heretics remain on the columns (illustration on the right)

The Nicene Creed said little about the Holy Spirit. A revised creed, proclaimed by the Council of Constantinople in 381 CE, described

the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of life, who proceeds from the Father, who together with the Father and the Son is to be adored and glorified, who spoke by the Prophets.

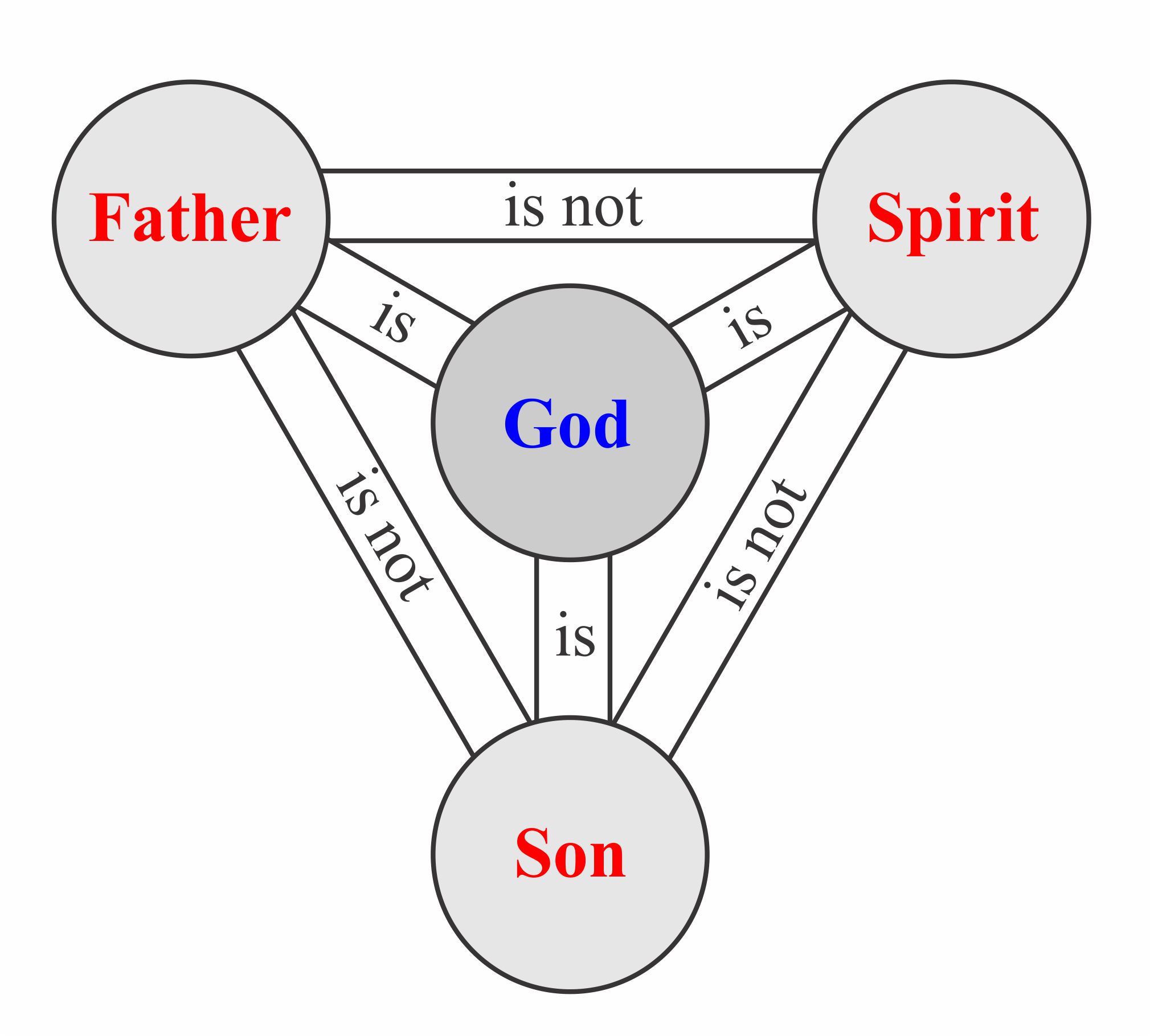

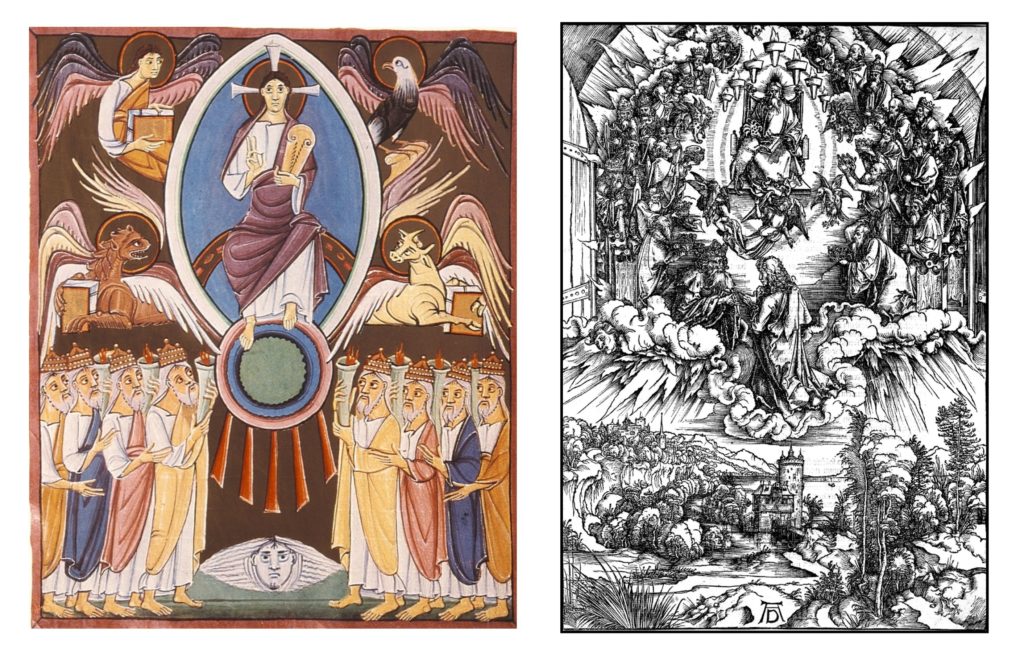

Christians were then left with the orthodox view of a Trinitarian God composed of three separate but consubstantial persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit. In the early Middle Ages this concept of the Godhead came to be represented by the shield of faith (scutum fidei), illustrated on the right. Three is one and one is three. An incomprehensible doctrine was thus promulgated by theologians at the behest of an emperor in an ultimately unsuccessful attempt to unite and prolong his empire.

The Latin Churches in the Eastern part of the Roman Empire later added the words “and the Son” (filioque) to describe the procession of the Spirit from the Father and the Son. To state that the Spirit proceeded only from the Father alone suggested an Arian heresy, i.e. that the Father was before the Son. The Eastern Church felt that this addition to the creed undervalued the importance of the Holy Spirit and subverted the authority of the Councils that wrote the original creed. The filioque controversy became one of the causes leading to the schism between the Eastern and Western Churches in 1054.

The creeds revised and proposed by the Ecumenical Councils were all focused on the nature of the Trinity. They also included the necessity of baptism, the remission of sins, the foundation of the church, the resurrection of the body and the life eternal. However, they failed to mention the main teachings of Jesus: the necessity to love one’s neighbors and to forgive them their trespasses.

The Triumph of Thomas Aquinas over the Heretics

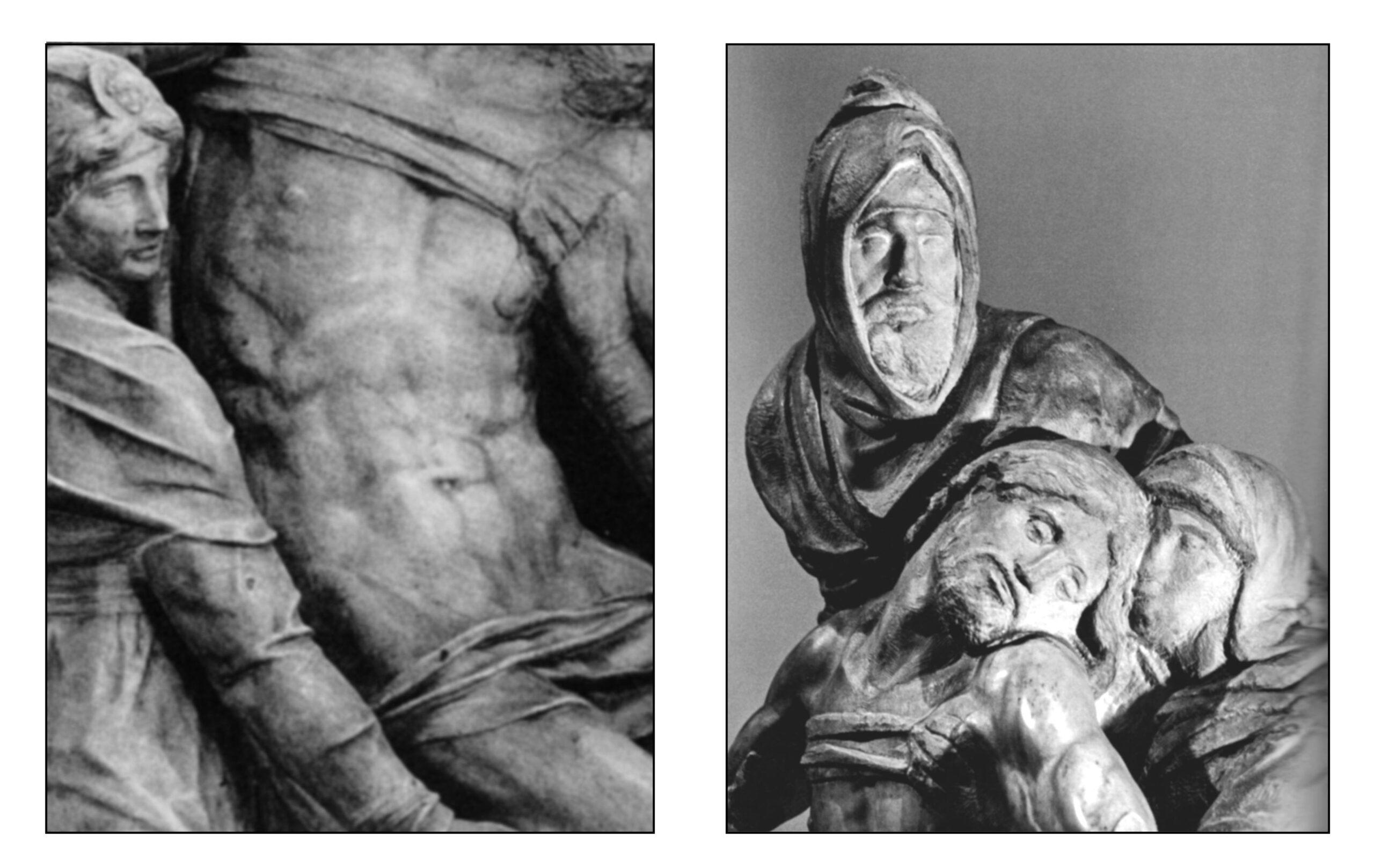

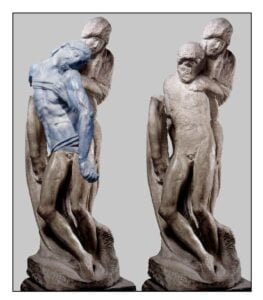

This post will conclude with a description of a Renaissance fresco by Filippino Lippi in the Carafa Chapel of the Church of Santa Maria Sopra Minerva in Rome. The fresco illustrates the early heresies of Christianity. This fresco was also described by Charles Freeman in the introduction to his 2002 book The Closing of the Western Mind. However, he used it not so much to illustrate the triumph of orthodoxy over heresy as to acclaim the ascent of reason, as represented by Aquinas and his Aristotelian logic, over the blind faith that had after the Council of Nicaea impeded rational thought.

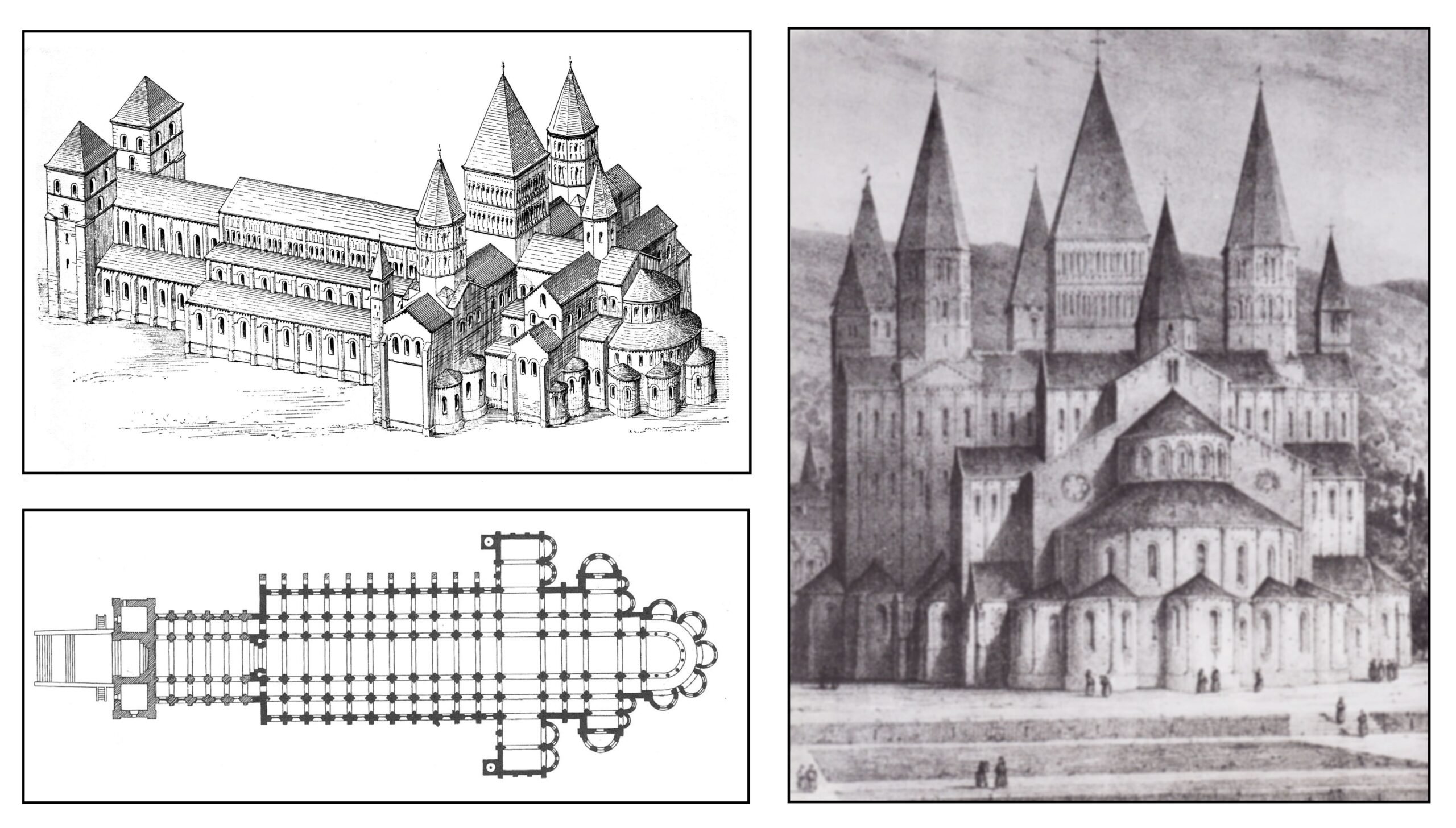

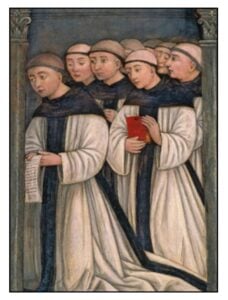

In 1280 the Dominicans began building a gothic church on the site of a Roman Temple to Minerva near the Pantheon. The interior of the church Santa Maria Sopra Minerva was finished by 1475, though the façade (designed by Carlo Moderno) was not completed until 1725. Cardinal Oliviero Carafa funded a chapel in the southern transept to be dedicated to the Virgin Mary and to Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274). From 1488 until 1493, Filippino Lippi (1457-1504), the illegitimate son of Fra Filippo Lippi and the nun Lucrezia Buti, painted a series of frescos in this chapel. These have been definitively described by Gail Geiger (1986), from whom most of the following comments derive. On the western wall of the chapel is The Triumph of Saint Thomas Aquinas over the Heretics:

At the top of the fresco, two putti display banners quoting Psalms 119:130 (118:130 in the Vulgate) guaranteeing the truth of the fresco.

Declaratio sermonum tuorum illuminat, et intellectum dat parvulis. [The entrance of thy words giveth light; it giveth understanding unto the simple.]

In the upper center of the fresco above the seated saint an opened book shows the quotation from Proverbs 8:7 with which Aquinas opened his Summa Contra Gentiles also known as Liber de veritate catholicae fidei contra errores infidelium [The book of the truth of the Catholic faith as against the errors of the infidels.]

Veritatem meditabitur guttur meum, et labia mea detestabuntur impium. [For my mouth shall speak truth; and wickedness is an abomination to my lips.] </p>

Thomas holds in his hands a book that quotes I Corinthians 1:19

Sapientiam sapientum perdam. [I will destroy the wisdom of the wise. (Paul is being ironic: he means to disprove the conclusions of those who foolishly pretend to wisdom, and replace them with the truth.)]

At his feet is an old man who is the personification of evil. He has been subdued by a banner quoting from the apocryphal Book of Wisdom 7:30:

Sapientia vincit malitiam. [Wisdom conquers evil]

Inscribed on the plaque below the saint’s throne are the words

Divo Thomae ob prastratam impietatem [To the divine Thomas for overthrowing heresy.]

Sitting beside Thomas are personifications of his knowledge and ability. On the left are Philosophy holding a book and Theology pointing heavenward. The face of Theology is illuminated with the serenity of her mystic vision. On the right are two of the liberal arts: Logic (Dialectica) controlling a snake as symbol of the syllogism, and Language (Grammatica) holding a pointer and instructing a young child.

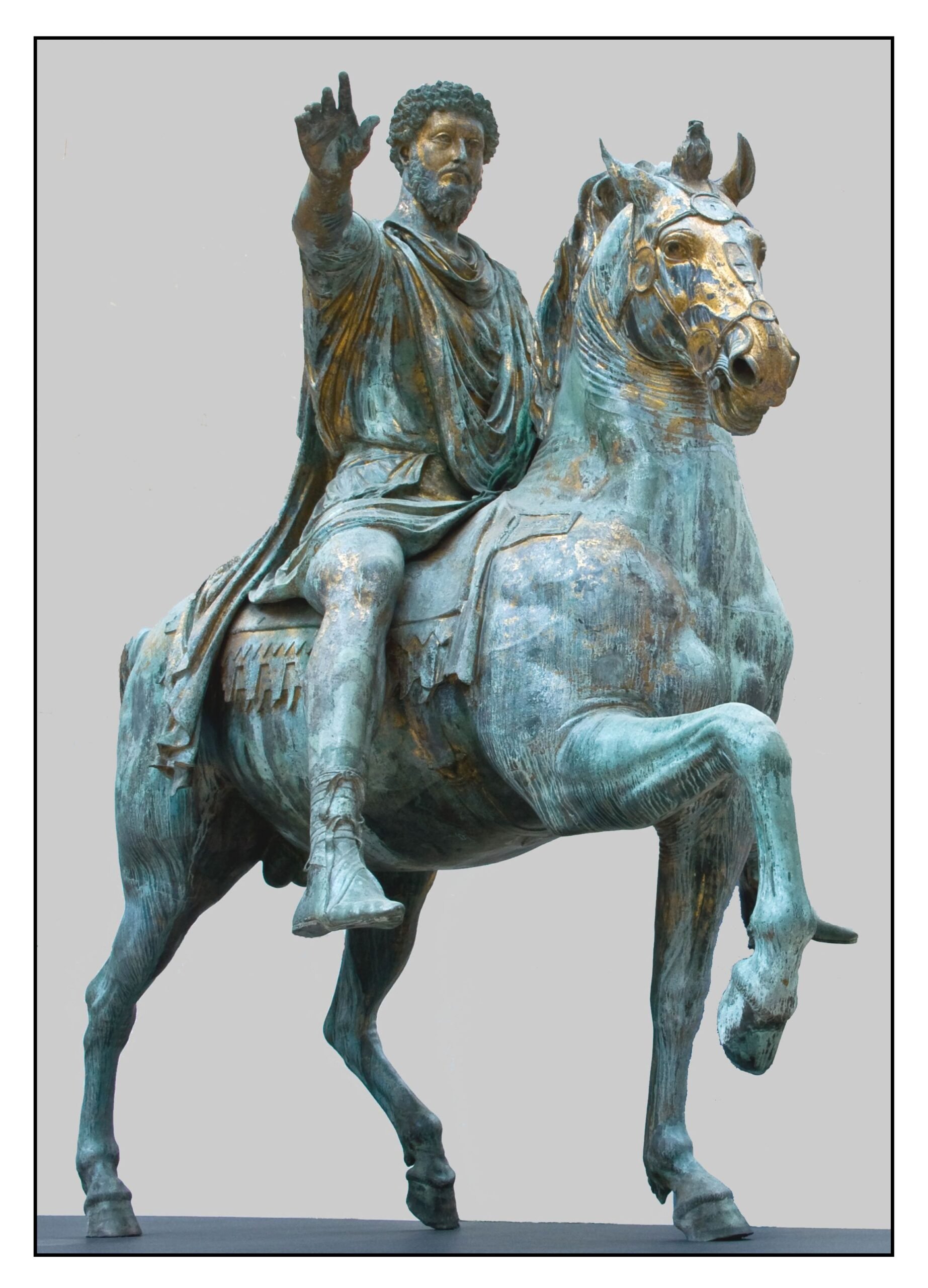

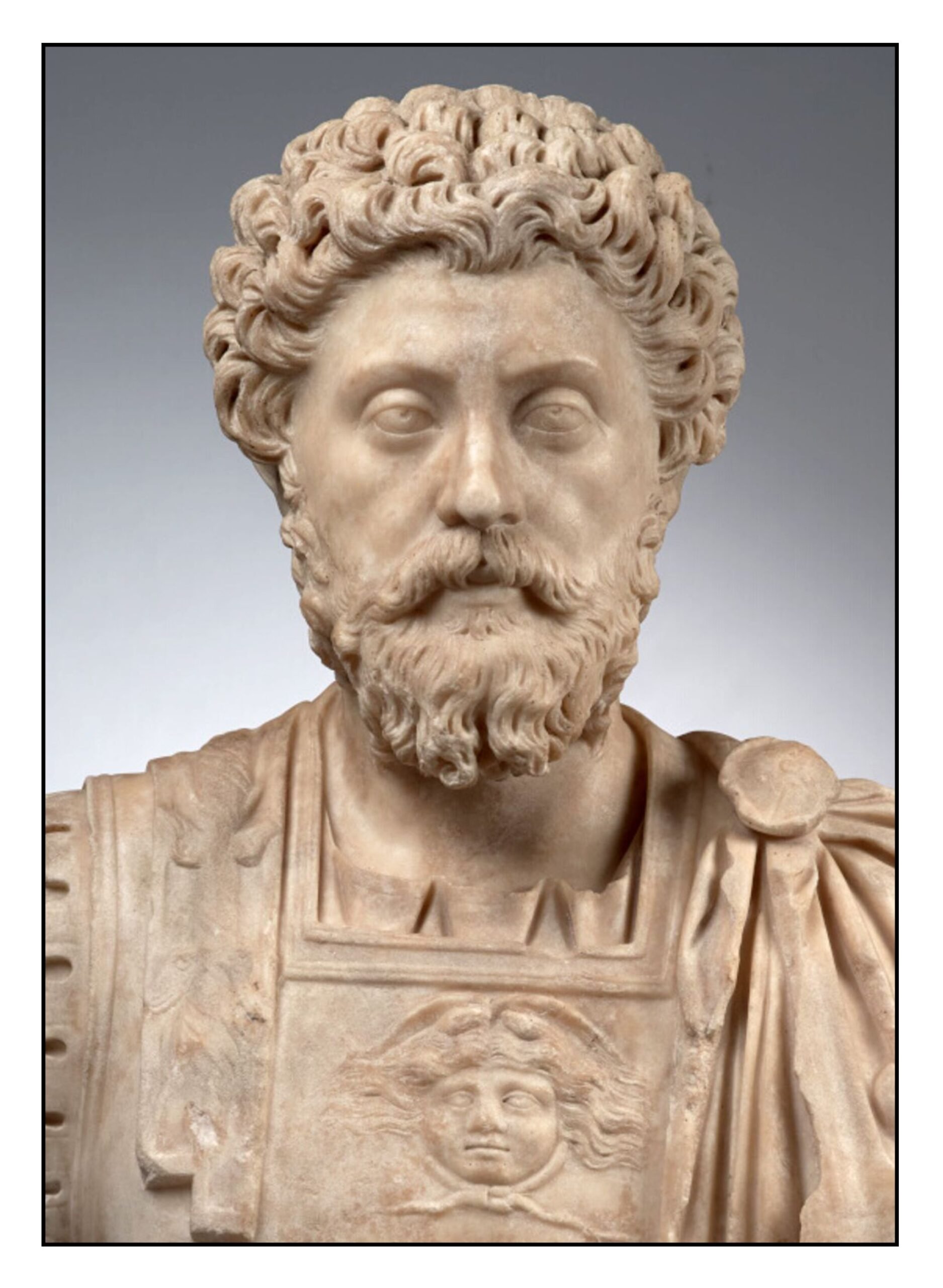

In the distant background on the left side of the fresco is the Statue of Marcus Aurelius. At the time the fresco was painted, this statue was considered to represent the Emperor Constantine the Great, who convened the Council of Nicaea in 325CE to settle the basic tenets of the Christian faith – as expressed in the Nicene Creed. This demonstrates the establishment of Church doctrine

In the background to the right can be seen the Porta di Ripa Grande on the Tiber. The papal fleet under the direction of Cardinal Carafa had left from this port in 1472 to wage war with the Venetians against the Turks, an expedition that briefly freed the city of Smyrna. This detail indicates the ongoing defense of doctrine against the infidels.

In the lower left of the fresco, a severe character identified by Geiger (1986) as Niccoli Orsini, the general of the papal army, brings forth a group of heretics to witness the end of their heresies. The most prominent of these is the bearded Arius. He believed that God the Father preceded God the Son and that there must have been a time then when Christ was not. His heresy is shown in the downcast papers:

Si Filius natus est, erat quando non erat Filius. [If the Son was born there was a time when the son was not.]

In the lower right of the fresco, a friar in black and white, identified by Geiger (1986) as Joachim Torriani, the Master General of the Dominican order, ushers to the front another group of heretics. The first of these is Sabellius, dressed in a red Roman toga, who believed that the three parts of the Trinity were simply modes of one God. The discarded papers show his error:

Pater a Filio non est alius nec spiritu sancto [The father is not different from the Son nor from the Holy Spirit].

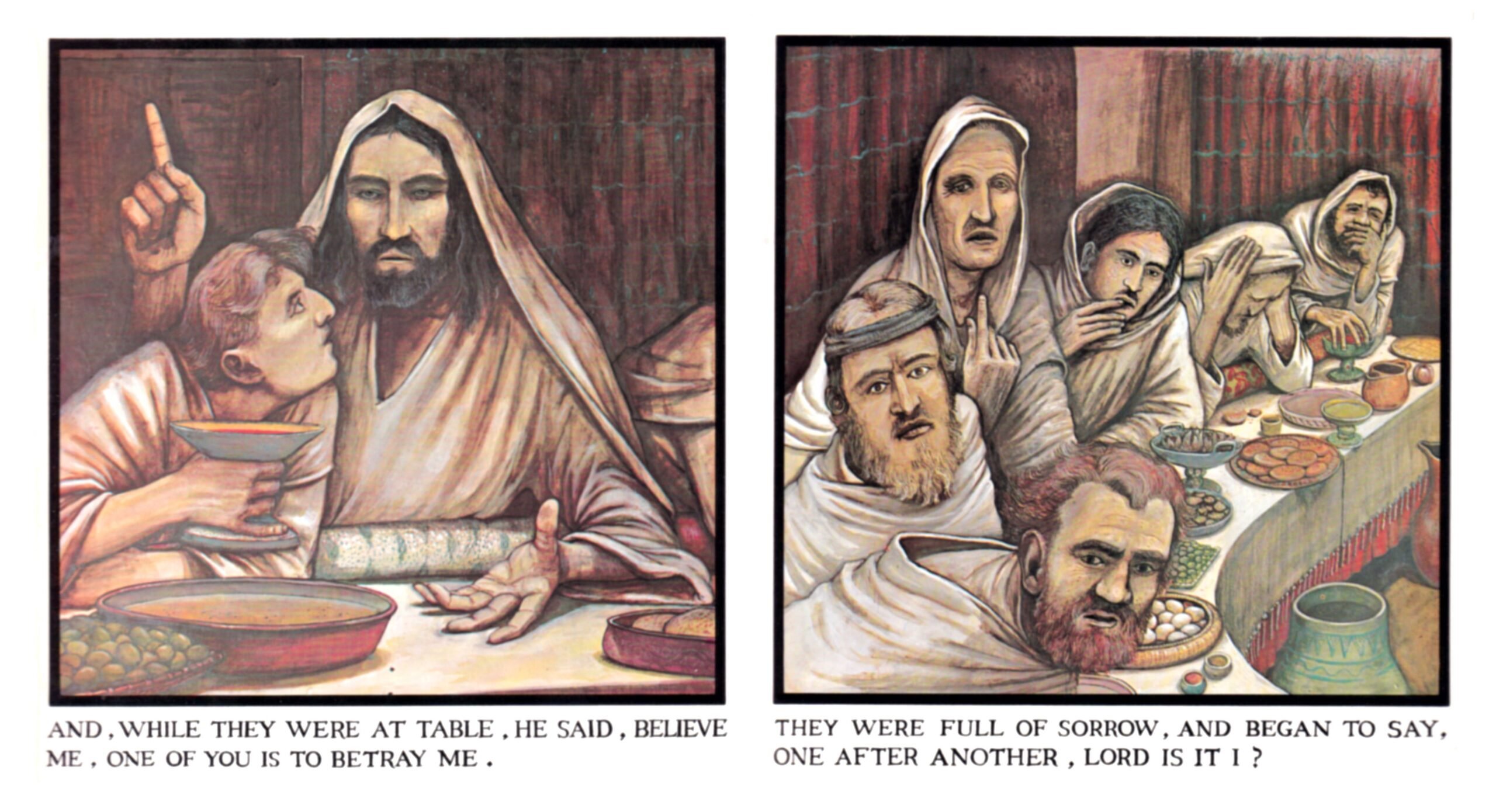

Did Aquinas really triumph over heresy? He certainly provided the logical underpinnings for what was considered orthodoxy. But his logic was strained. And sometimes it was completely wrong. Aquinas used Aristotle’s metaphysics to explain the Roman Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation: that the substance of the bread and the wine were changed during the Eucharist into the actual body and blood of Christ. This ceremony of the Eucharist (also known as Holy Communion) derives from Christ’s instructions to his disciples at the Last Supper:

And he took bread, and gave thanks, and brake it, and gave unto them, saying, This is my body which is given for you: this do in remembrance of me.

Likewise also the cup after supper, saying, This cup is the new testament in my blood, which is shed for you. (Luke 22: 19-20)

Thomas Aquinas proposed that, since objects have both a “substance” (which defines what they are) and “accidents” or “appearances” (which determines how we perceive them), during the Eucharist, the substances of the bread and wine are changed even though they appear the same (Pruss, 2011). Aristotle’s ideas about substance and accidents have no basis in our modern understanding of nature. Protestants consider the Eucharist to be a symbolic ceremony: the bread and wine does not actually change to the body and blood of Christ.

Concluding Comments

When one does not have evidence for what one believes, one can gain some confidence that one is right if others believe the same way. This is the main force behind proselytism: the drive of the religious to convince others to join them in their belief. Furthermore, those that believe differently must be condemned as heretics or the confidence of the orthodox believers might falter. Religious organizations often propose that spiritual rewards – for example, forgiveness of sins and life everlasting – only come to those who believe in the orthodox doctrines. Priests who determine what is orthodox, reward the believers and excommunicate the heretics have tremendous power. Being human, they may often use this power for selfish reasons. Jesus preached compassion and forgiveness. He argued against the codification of belief and would be saddened by those who endlessly dispute about what they cannot understand, and who condemn those that choose to believe differently.

References

Buzzard, A., & Hunting, C. F. (1999). The doctrine of Trinity: Christianity’s self-inflicted wound. Christian Universities Press.

Crossan, J. D. (1991). The historical Jesus: the life of a Mediterranean Jewish peasant. HarperCollins.

Dünzl, F. (2007). A brief history of the doctrine of the Trinity in the early church. T & T Clark.

Ehrman, B. D. (2012). Did Jesus exist? the historical argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperOne.

Evans, G. R. (2003). A brief history of heresy. Blackwell Publishing.

Freeman, C. (2002). The closing of the Western mind: the rise of faith and the fall of reason. Heinemann.

Funk, R. W., Hoover, R. W., & Jesus Seminar. (1996). The five Gospels: the search for the authentic words of Jesus, a new translation and commentary. Scribner

Geiger, G. L. (1986). Filippino Lippi’s Carafa Chapel: Renaissance art in Rome. Sixteenth Century Journal Publishers.

Henderson, J. B. (1998). The construction of orthodoxy and heresy: Neo-Confucian, Islamic, Jewish, and early Christian patterns. State University of New York Press.

Hillar, M. (2012). From Logos to Trinity: the evolution of religious beliefs from Pythagoras to Tertullian. Cambridge University Press.

Jefford, C. N. (2013). Didache: The teaching of the twelve apostles. Polebridge Press.

Luhrmann, T. (2018). The faith frame: or, belief is easy, faith is hard. Contemporary Pragmatism, 15(3), 302–318.

MacIntosh J.J. (1994). Belief-in revisited: a reply to Williams. Religious. Studies, 30, 487-503.

Meier, J. P. (1991). A marginal Jew: rethinking the historical Jesus. Doubleday.

O’Loughlin, T. (2010). The Didache: a window on the earliest Christians. Baker Academic.

Phan, P. C. (2011). Developments of the doctrine of the Trinity. In Phan, P. C. (Ed). The Cambridge companion to the Trinity. (pp 3-120). Cambridge University Press.

Price, H. H. (1965). Belief ‘in’ and belief ‘that.’ Religious Studies, 1, 5-27

Pruss, A. R. (2011). The Eucharist: real presence and real absence. In T. P. Flint & M. C. Rea (Eds) The Oxford Handbook of Philosophical Theology (pp 512-538). Oxford University Press.

Robinson, J. (2011). The gospel of the historical Jesus. In T. Holmén & S. E. Porter, (Eds) Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus Volume I (pp 447-474). Brill

Schaberg, J. (1980). The Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit: an investigation of the origin and meaning of the triadic phrase in Matt 28: 19b. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Schweitzer, A. (1906, translated by Montgomery, W., 1910). The quest of the historical Jesus: a critical study of its progress from Reimarus to Wrede. A& C Black

Schwitzgel, E. Belief. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Thellman, G. S. (2019). The narrative-theological function of Matthew’s baptism command (Matthew 28:19b). Anafora, 6(1), 81-106.

Tuggy, D. (2020a). Trinity. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Tuggy, D. (2020b). History of Trinitarian Doctrines. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Wainwright, E. (2011). Like a finger pointing to the moon: Exploring the Trinity in/and the New Testament. In P. C. Phan (Ed.) The Cambridge Companion to the Trinity (pp 33-48). Cambridge University Press

Williams, J. N. (1992). Belief-in and belief in God. Religious Studies, 28, 401-406.

Wilson, A. N. (1992). Jesus. W.W. Norton.

Young, F. (2006). The Trinity and the New Testament. In C. Rowland, C., & C. M. Tuckett, (Eds). The Nature of New Testament Theology (pp 286–305). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.