The White Monks

In 1098 a small group of monks left the Benedictine monastery of Molesme in Burgundy to live in the forest of Cîteaux (Latin Cistercium) just south of Dijon. They considered their original home too lax and luxurious, and wished to return to the austere life of solitude, chastity, poverty and manual labor that St Benedict had originally proposed in the 6th Century. They distinguished themselves from the Benedictines by wearing undyed white robes rather than black. Over the next hundred and fifty years, the small monastery founded by these “white monks” at Cîteaux became the center of the Cistercian Order, which linked together over 500 abbeys in Europe, extending from Portugal to Estonia and from Sicily to Norway. The Cistercians were noted for the proficiency of their agriculture, the fervor of their scholarship, and the beauty of their buildings. This post comments on their achievements.

Early Christian Monasticism

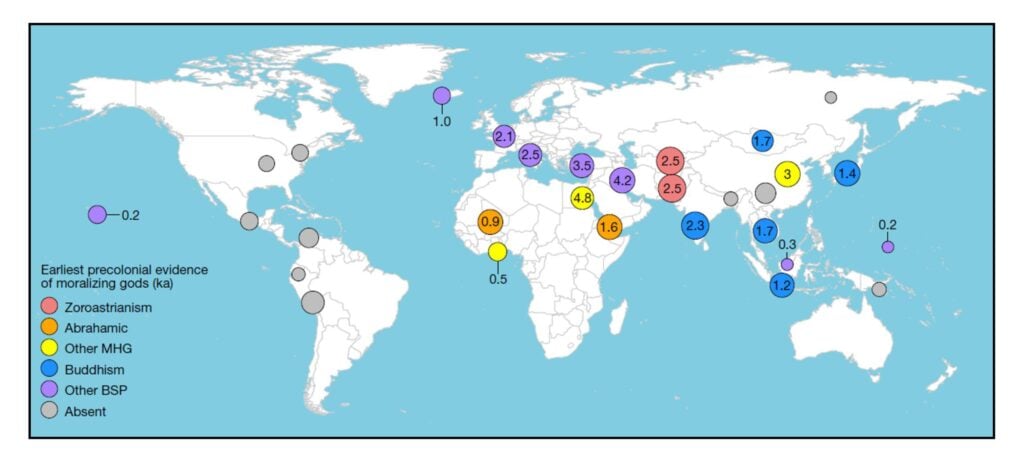

The earliest histories of many different cultures record how some individuals renounced the pleasures of the world and lived apart from society (Davis, 2018). In Christian times these were called ascetics (Greek askein exercise) and hermits (Greek eremos desert). However, many of these individuals could not completely reject the society of others, and formed themselves into communities. Then they were called by the contradictory terms “monks” (Greek monos alone) or “cenobites” (Greek koinos community + bios life). The monastery became a place where one could practise a spiritual rather than a worldly life in the limited company of other like-minded individuals.

Pachomius the Great (292-348 CE) is usually considered the founder of Christian monasticism. After years of studying with the hermit Palaemon, he set up a small community of monks in Tabbennisi in Upper Egypt and proposed a set of rules to govern their life. The main rules required a strict scheduling of prayers and psalms throughout the day and night, obedience to the leader of the community, keeping away from members of the opposite sex, following a vegetarian diet, limiting any unnecessary speech, and performing manual labor. Pachomius was called Abba (father) by his disciples: from this came the term “abbot” and “abbey.”

Many other Christians retired to the Egyptian deserts to devote themselves to contemplation and worship. The most famous of these were Anthony the Great (251-356 CE) who lived as a hermit in the Eastern Desert and then organized his disciples into a monastery, and Paul of Thebes (227-341 CE) who lived alone in the desert from age of 16 until his death at the age of 113 years. The illustration below shows a 1640 painting of Paul by Jusepe de Ribera

Pachomius, Anthony, Paul and their colleagues became known as the “Desert Fathers” (Dunn, 2007; Wortley, 2019). Their teachings were collected together as the Apothegmata ton Pateron – the “Sayings of the Fathers” (Merton,1960) of which the following is an example:

Just as bees are driven out by smoke, and their honey taken away from them, so a life of ease drives out the fear of the Lord from a man’s soul and takes away all his good works.

Monasticism was established in Western Europe by Saint Benedict (480-543 CE) who founded several monasteries in central Italy, most famously at Monte Cassino in the mountains south of Rome. The Rule of Saint Benedict updated and extended the general principles of monasticism – poverty, charity, silence, obedience, prayer and labor – that had been proposed by Pachomius. His followers became the Benedictines, and their monasteries prospered.

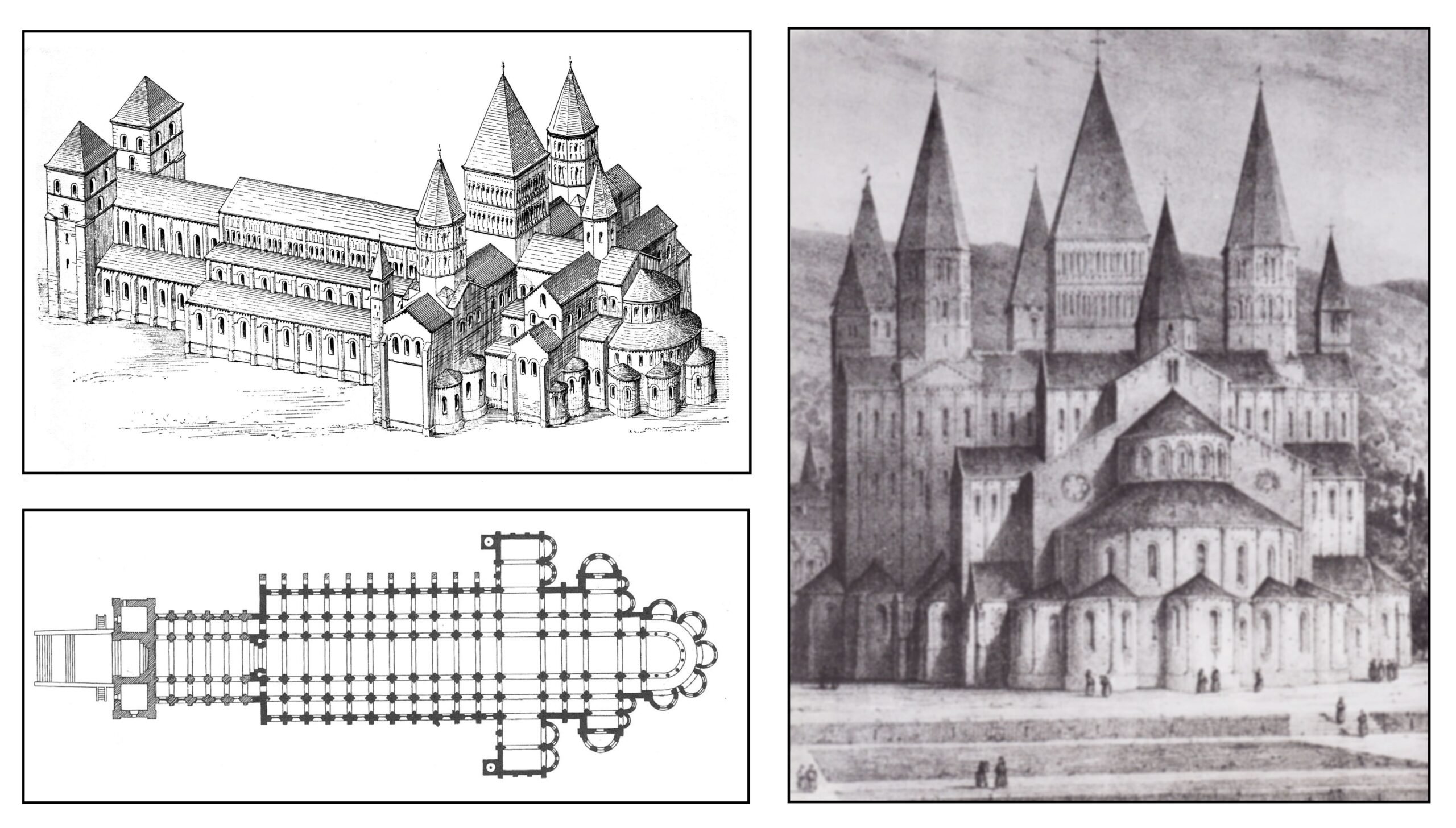

As the years passed, however, the monks no longer participated in manual labor, leaving that to the “lay brothers” who joined the monastery in hope of salvation. The abbey churches became richly decorated, the monk’s quarters became palatial, the diet became sumptuous, the communion vessels were made of gold and silver, and the vestments were sewn with silk and jewels. The most luxurious of the Benedictine monasteries was the Abbey of Cluny founded in 910 CE in Burgundy halfway between Dijon and Lyon. The abbots of Cluny established many daughter monasteries from which they derived much of the revenue to support their building. In its final form (1088-1130 CE) the abbey church at Cluny (illustrated below) was the world’s largest church, with 6 bell towers, a overall length of 555 ft, 5 naves with the central nave 98 ft high, and the dome at the crossing 118 ft high.

The Monastery at Cîteaux

Many monks rebelled against the luxury of the Benedictines. In the period between 1050 and 1250 several new monastic orders were founded, among them: the Carthusians (1084), the Carmelites (1150), and the Order of Saint Augustine (1244). The most successful of these were the Cistercians founded by Robert de Molesme in 1098.

Histories written later described how Robert de Molesme (1028-1111), his prior Alberic and his secretary Stephen Harding, and 21 other monks became disillusioned with the current laxity of the Benedictines and founded a new community at Cîteaux in 1098:

After many labors, therefore, and exceedingly great difficulties … they at length attained their desire and arrived at Cîteaux – at that time a place of horror and of vast solitude. But judging that the harshness of the place was not at variance with the strict purpose they had already conceived in mind, the soldiers of Christ held the place as truly prepared for them by God: a place as agreeable as their purpose was dear. (quoted in Bruun and Jamroziak, 2013)

The “place of horror and of vast solitude” directly quotes the description of Jacob’s inheritance in Deuteronomy 32:10, which in the Vulgate reads in loco horroris, et vastae solitudinis (Bruun and Jamroziak, 2013). Modern historians believe that the site of the new monastery was actually far more congenial to settlement (Berman, 2010).

Robert was soon recalled back to Molesme, and the early success of Cîteaux was largely the work of the English monk Stephen Harding (1060-1134), who set out the governing rules for the order – the Carta Caritatis (Merton & O’Donnell, 2015). He convinced other communities to join with them in their devotion to a strict interpretation of the rule of Saint Benedict concerning poverty, charity, chastity, and obedience as outlined in the Rule of Saint Benedict.

However, the new order was more egalitarian than the Benedictines. Even the abbot could be criticized and punished for transgressing the rule. Lay brothers were integrated into the monastery rather than simply exploited. These brothers lived under same conditions as monks but, because they could not read or write, they did not participate in the singing of psalms or the copying of manuscripts. The Cistercians also founded numerous convents for women, the first being Le Tart Abbey in 1132 only a few miles from Cîteaux.

For clothing, monks were limited to two white robes, one black or brown scapular (over the shoulder) with cowl (hood) to wear over the robe when the monk was working in the fields, and one pair of stockings and shoes. The monks were tonsured – their remaining hair symbolizing Christ’s crown of thorns. Lay brothers were not tonsured. The illustration on the right shows a painting of Cistercian monks from Staffarda Abbey in Northern Italy.

The abbots of the affiliated monasteries reported yearly at the meeting of the Annual General Chapter in Cîteaux, but the individual abbeys were largely autonomous. Since they were not required to pay tribute to the mother abbey, new monasteries preferred to become Cistercian rather than Benedictine. In addition, the Cistercians stipulated an arms-length relationship to donors and benefactors. These were not allowed to enter the cloister, to erect family monuments within the abbey church or to be buried in the monastery grounds.

As well as being an able administrator, Harding was an important scholar and talented scribe Reilly, 2018). Over the first few years of his tenure as abbot of Cîteaux (1108-1133), he and his monks produced a new illustrated version of the Vulgate Bible of Saint Jerome (342-420 CE). The following shows the section of I Samuel 17 dealing with David and Goliath.

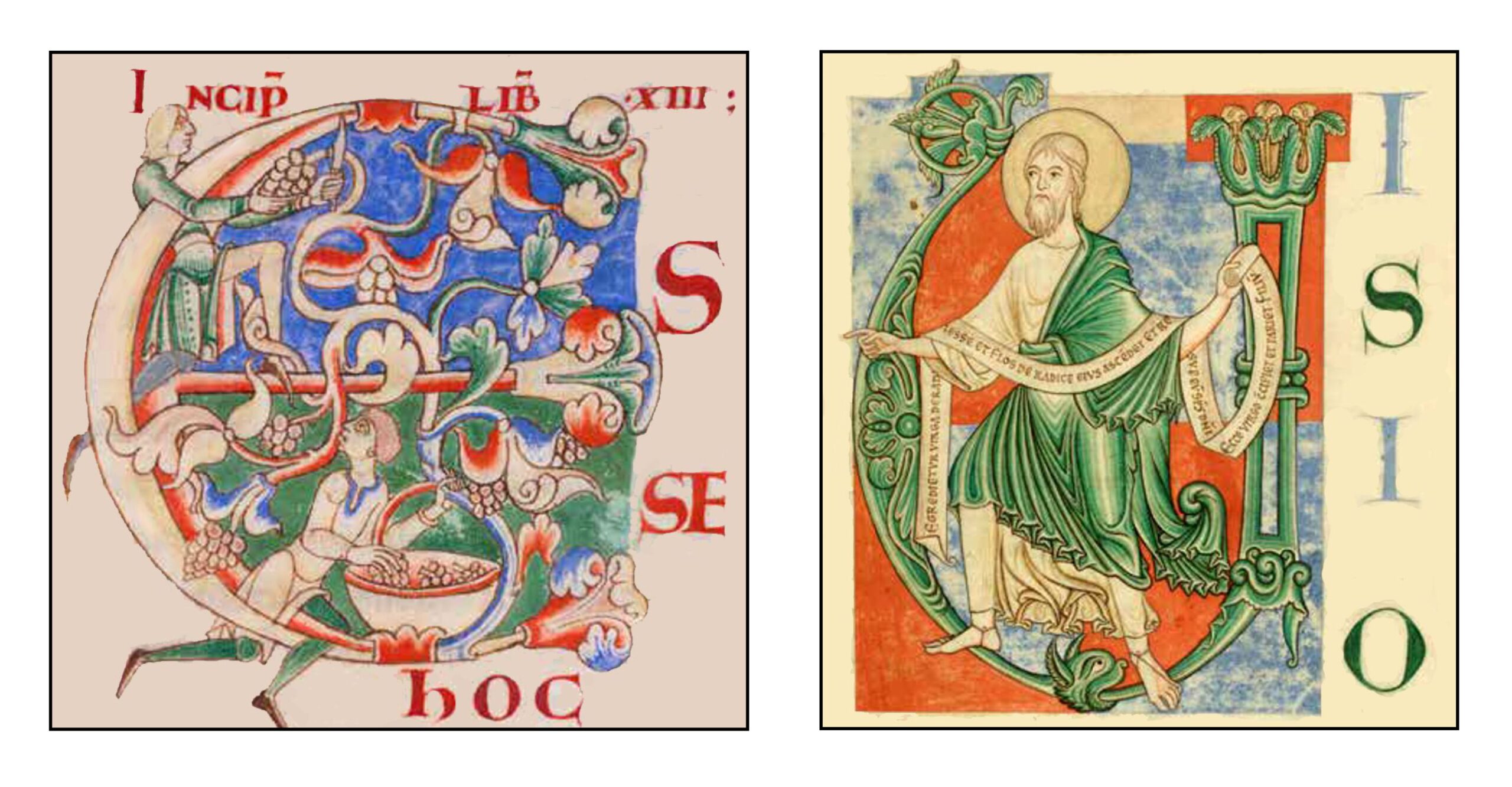

Among the many manuscripts produced in the monastery under Harding were a new edition of the Moralia in Job by the 6th-Century pope Gregory I, and a copy of Jerome’s Commentary on Isaiah. On the left below is the letter “E” from the beginning of Book XIII of the Moralia. The illumination shows monks at their work harvesting the grapes, just like Gregory is harvesting meaning from the Book of Job. On the right is shown the letter “V” from the beginning of Jerome’s commentary – the initial verse of Isaiah in the Vulgate begins Visio Isaiae (The vision of Isaiah …). In the illumination the prophet carries a banner detailing two of his main prophecies: that the Messiah will be a descendant of the house of Jesse, father of King David (Isaiah 11:1, Et egredietur virga de radice Jesse) and that a virgin shall conceive and bear a son (Isaiah 7:14, Ecce virgo concipiet, et pariet filium).

Bernard of Clairvaux

In 1113, Bernard de Fontaine (1090-1153), a scion of the highest Burgundian aristocracy, joined Stephen Harding at the monastery of Cîteaux, bringing with him 30 other young noblemen. Impressed by the young monk, in 1115 Harding sent Bernard to the Champagne region of France to found the monastery of Clairvaux (Latin Clara Vallis, clear valley), where he served as the abbot until his death (Holdsworth, 2013).

Bernard was eloquent and charismatic. In a 1953 encyclical Pope Pius called him “Doctor Mellifluus” and considered him the last of the “Fathers of the Church” (though these are generally only recognized up to the 8th Century). The following quotations are from his series of sermons on the Song of Songs, which he interprets as describing the marriage between the soul and Christ:

The soul seeks the Word, and consents to receive correction, by which she may be enlightened to recognize him, strengthened to attain virtue, molded to wisdom, conformed to his likeness, made fruitful by him, and enjoy him in bliss. (Thornton & Varenne, 2007, pp 226-227).

For there are some who long to know for the sole purpose of knowing, and that is shameful curiosity; others who long to know in order to become known, and that is shameful vanity. To such as these we may apply the words of the Satirist: “Your knowledge counts for nothing unless your friends know you have it.” There are others still who long for knowledge in order to sell its fruits for money or honors, and this is shameful profiteering; others again who long to know in order to be of service, and this is charity. Finally, there are those who long to know in order to benefit them selves, and this is prudence. (Thornton & Varenne, 2007, p 156)

Bernard derived much of his faith from mystical contemplation. He was particularly devoted to the Virgin Mary and legends describe how he experienced visions of Mary. He was often called “Mary’s Troubadour.” The illustration below shows Fillipino Lippi’s 1487 altarpiece The Apparition of the Virgin to St Bernard now in the Benedictine Abbey (Badia) in Florence. Seated at his writing desk in his white robe, Bernard is suddenly surprised by the Virgin and a group of angels floating before him. In the dark recess in the rocks behind him is the Devil biting on his chains. The quotation on the rock beside him is from Epictetus: Sustine et abstine, urging restraint and abstinence. In the background other monks gather to wonder at the vision, a young monk brings an elderly brother to see what is happening, and a sick patient is carried toward the abbey. In the right foreground is Francesco de Pugliese, the donor of the altarpiece.

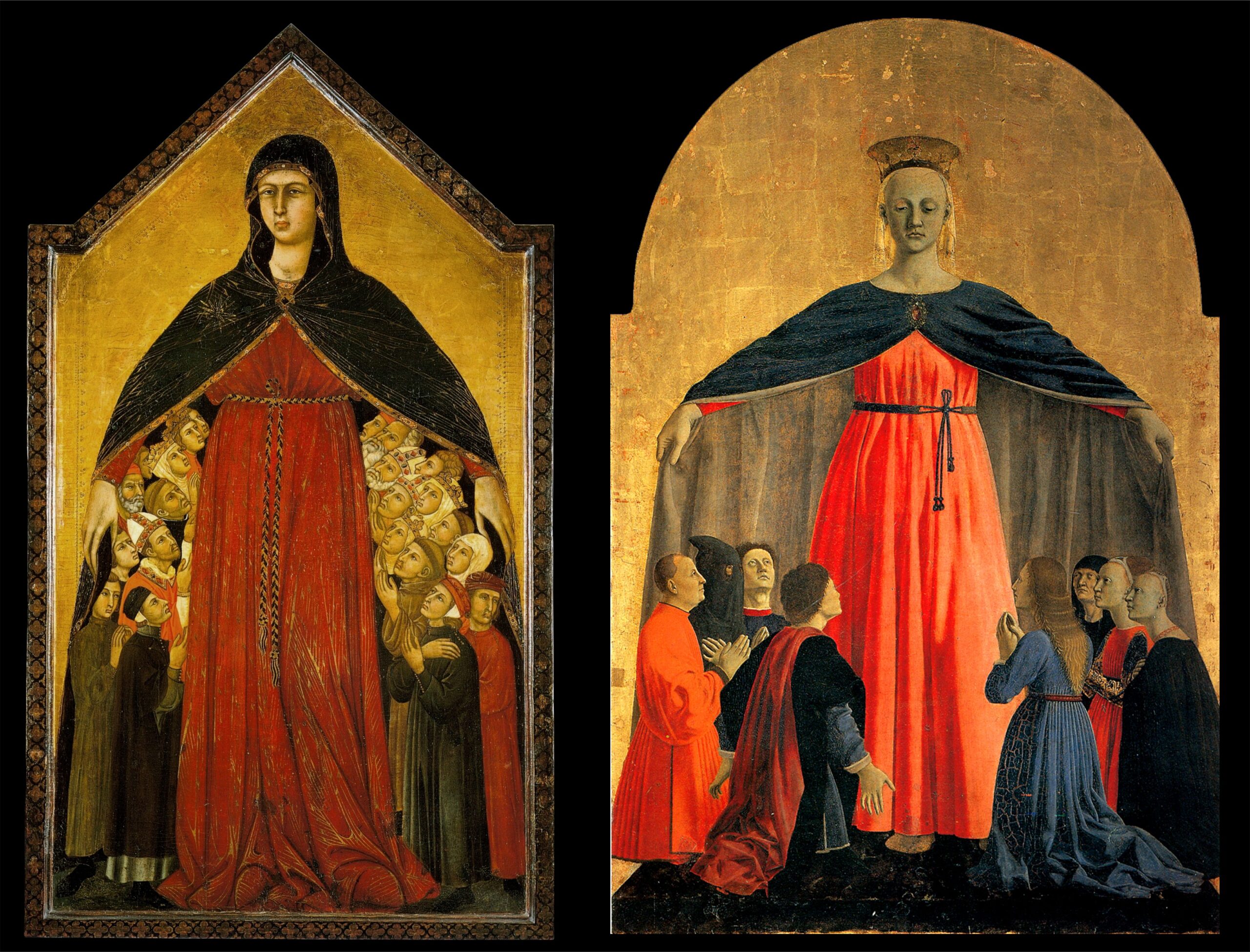

Early in their history, the Cistercians decreed that all their monasteries should be dedicated to the Mary, Queen of Heaven, and that all abbey seals should bear her image. The close association between the Cistercians and Mary contributed significantly to the success of the order. This was the age wherein the cult of the Virgin flourished.

Early in their history, the Cistercians decreed that all their monasteries should be dedicated to the Mary, Queen of Heaven, and that all abbey seals should bear her image. The close association between the Cistercians and Mary contributed significantly to the success of the order. This was the age wherein the cult of the Virgin flourished.

Bernard was highly involved in the politics and controversies of his age. Over many years he disputed with the philosopher Pierre Abélard about the nature of the Trinity, with Bernard claiming that this could only be understood by faith and could not be demonstrated by logic. Pope Benedict XVI later called their opposing approaches the “theology of the heart” and the “theology of reason.” Bernard convinced the pope to support the Knights Templar, a militant monastic order founded in 1119 by a group of French knights, one of which was Bernard’s uncle. In a fiery sermon in Vézelay, he urged on the Second Crusade (1147-1150), and was abashed when this came to naught.

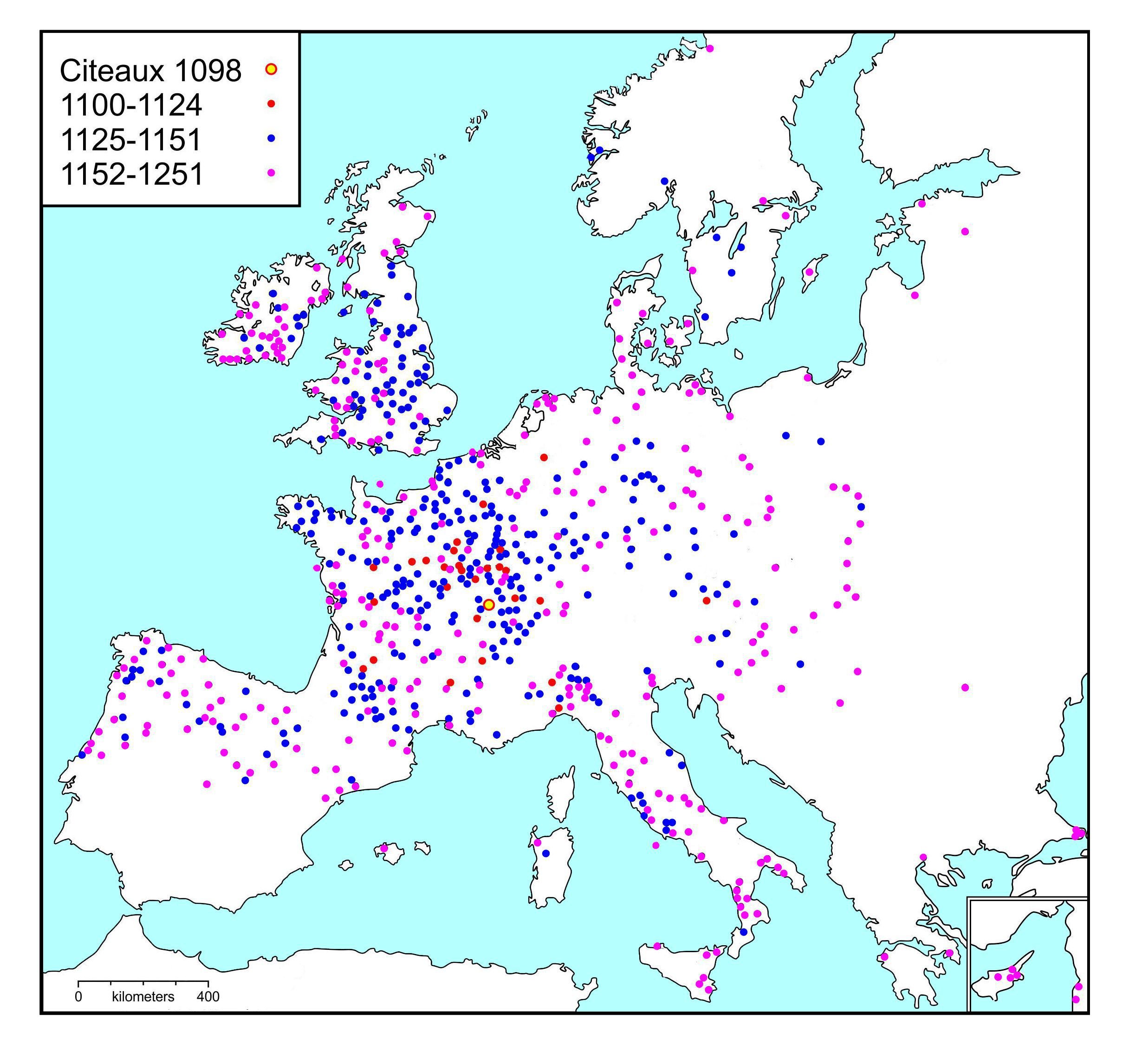

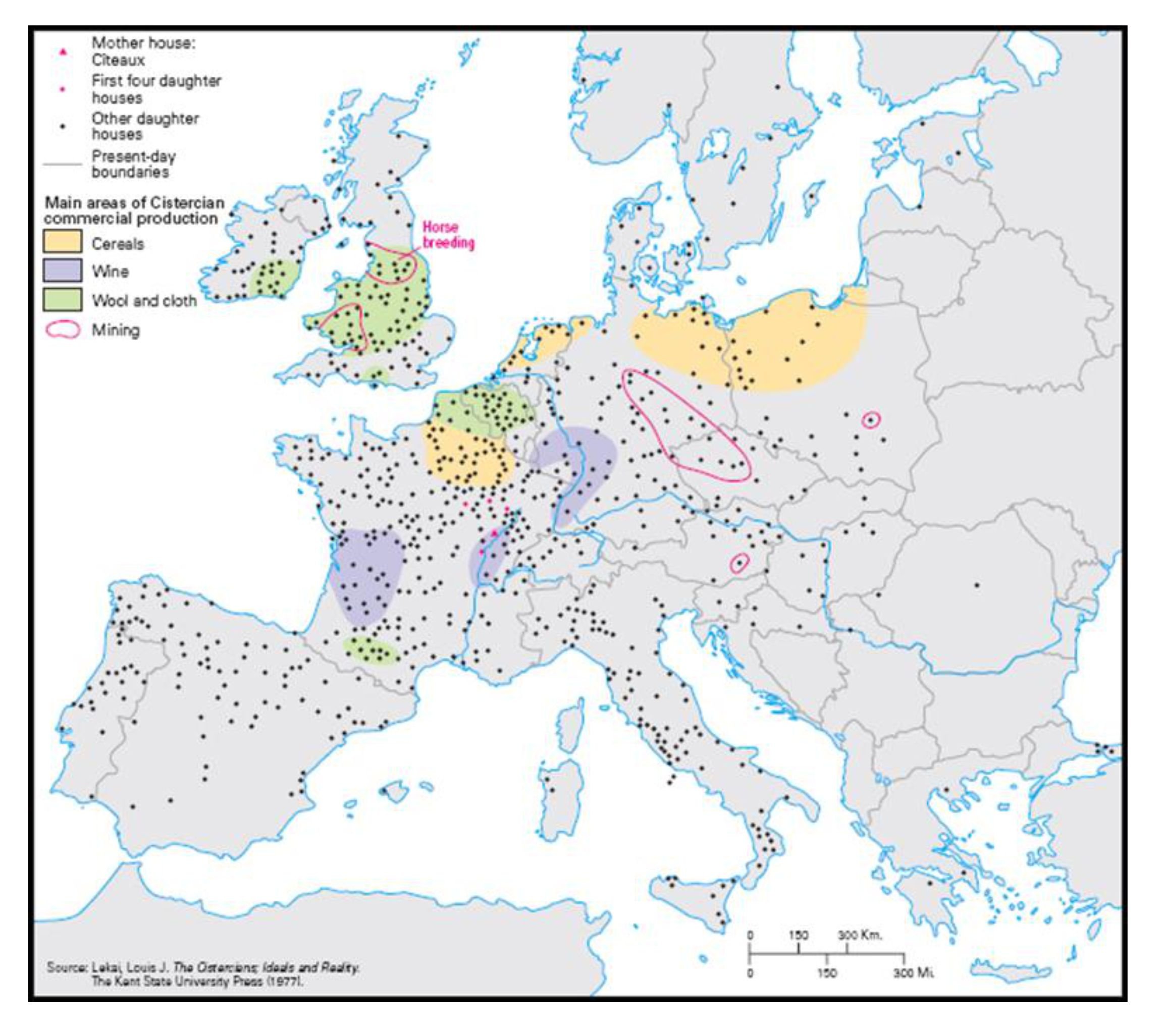

Most importantly he urged his monks to become soldiers of Christ and dispatched them to all the corners of Europe. Through their influence hundreds of monasteries were founded or became affiliated to the Cistercian order. The map below shows the spread of Cistercian abbeys through Europe. Clairvaux was the mother house (or grandmother house) for most of the abbeys in England and Northern France, and for many of the abbeys in Spain and Italy. The greatest Cistercian expansion was in the first fifty years (red and blue dots). Over the next century the expansion continued (purple dots). Then the Black Death laid waste to Europe from 1346 to 1353, and everything slowed down. Although most of the abbeys maintained their power, a few became deserted and fell into ruins. Over the years the abbeys slowly regained their prominence and the number of active Cistercian abbeys crested at around 700 by the time of the Reformation in the early 16th Century.

Architecture

Cistercian monasteries were typically located in valleys. The stream or river running through the valley provided fresh water for drinking and cooking and took away all the biodegradable waste produced in the abbey. Many of the Cistercian abbeys have variants of “valley” or “fountain” in their name. An anonymous Latin ditty describes the differences between the main Catholic orders:

Bernardus valles Bernard loved the valleys

Colles Benedictus amavit, Benedict the hills

Oppida Franciscus Francis the small towns

Magnas Ignatius urbes. and Ignatius the great cities

The founding monks either lived in temporary wooden buildings or remained at the mother abbey during the ten to twenty years that it took to build the stone church and monastery buildings. at the site, most of the work was carried on by dedicated stone-masons supervised by master-builders (the first architects). some of these master-builders may have been monks but most were simply professionals who travelled from site to site. since the stone was obtained from local quarries, the texture of the walls differs from abbey to abbey. Fernand Pouillon’s novel Les Pierres Sauvages vividly describes the building of the abbey of Le Theronet in Provence over the years 1160-1176.

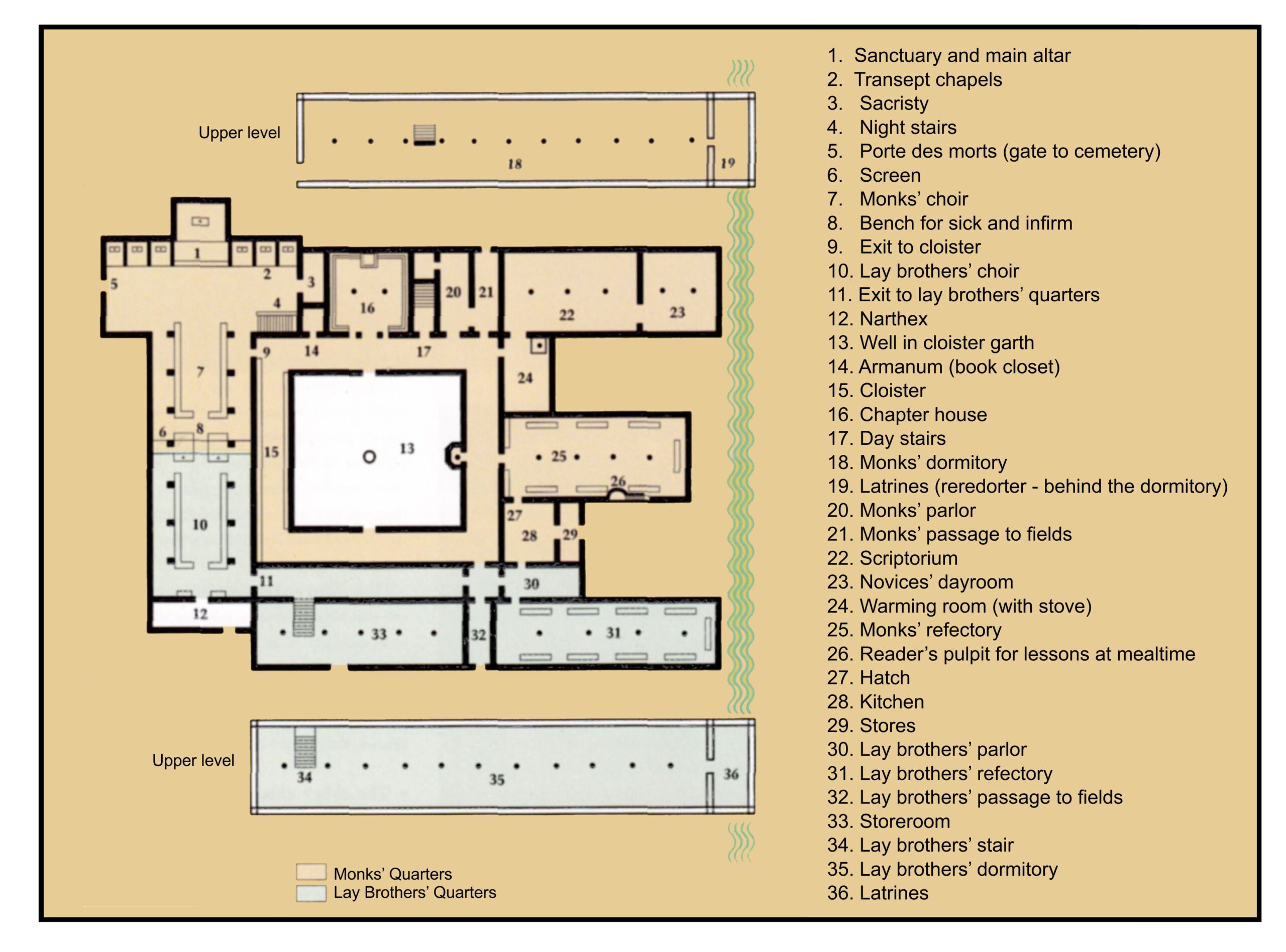

The following diagram (modified slightly from Gaud & Leroux-Dhuys, 1998, p 52; see also Tobin, 1995, p 21) shows the typical layout of a Cisterican monastery. The basic plan was adapted to the specific site, but was nevertheless remarkably consistent from abbey to abbey:

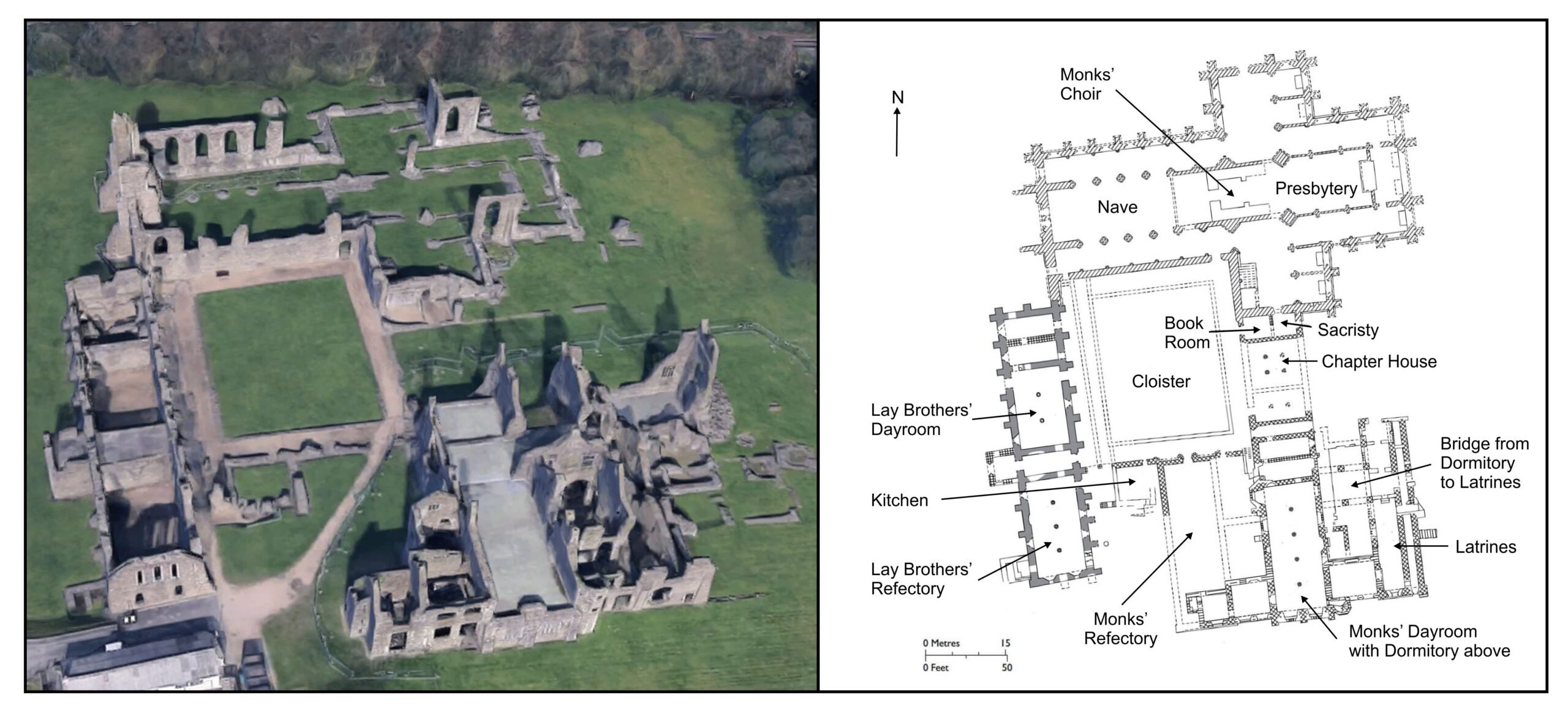

The illustration below shows the ruins of Neath Abbey in South Wales as viewed on Google Maps and a plan of the abbey from the Medieval Heritage website. I am partial to his abbey since Neath was my father’s home town, and I visited the abbey as a child. Note that the orientation is rotated 90˚ clockwise from the preceding plan so that North is upward.

The illustration below shows the ruins of Neath Abbey in South Wales as viewed on Google Maps and a plan of the abbey from the Medieval Heritage website. I am partial to his abbey since Neath was my father’s home town, and I visited the abbey as a child. Note that the orientation is rotated 90˚ clockwise from the preceding plan so that North is upward.

Bernard of Clairvaux criticized the luxurious decoration of the Cluniac churches. In an Apologia written in 1128 he remarked

I say nothing of the enormous height, extravagant length and unnecessary width of the churches, of their costly polishings and curious paintings which catch the worshipper’s eye and dry up his devotion … Let these things pass, let us say they are all to the honor of God. Nevertheless, just as the pagan poet Persius inquired of his fellow pagans, so I as a monk ask my fellow monks: … “Tell me, poor men, if you really are poor what is gold doing in the sanctuary?”

… The church is resplendent in her walls and wanting in her poor. She dresses her stones in gold and lets her sons go naked. The eyes of the rich are fed at the expense of the indigent. The curious find something to amuse them and the needy find nothing to sustain them.

He also thought that the various figurative sculptures on the capitols of the pillars and on the gargoyles of the roof had no place in a monastery, where they would only serve to distract the monks from their contemplation.

The directives of the early Cistercian Chapters stressed the austerity of the monastery buildings. Everything unnecessary was to be rejected: “towers, ornate pavements, coloured-glass windows , figurative paintings, sculpture, bells, images (except that of Christ ) and ornaments” (Coomans, 2013).

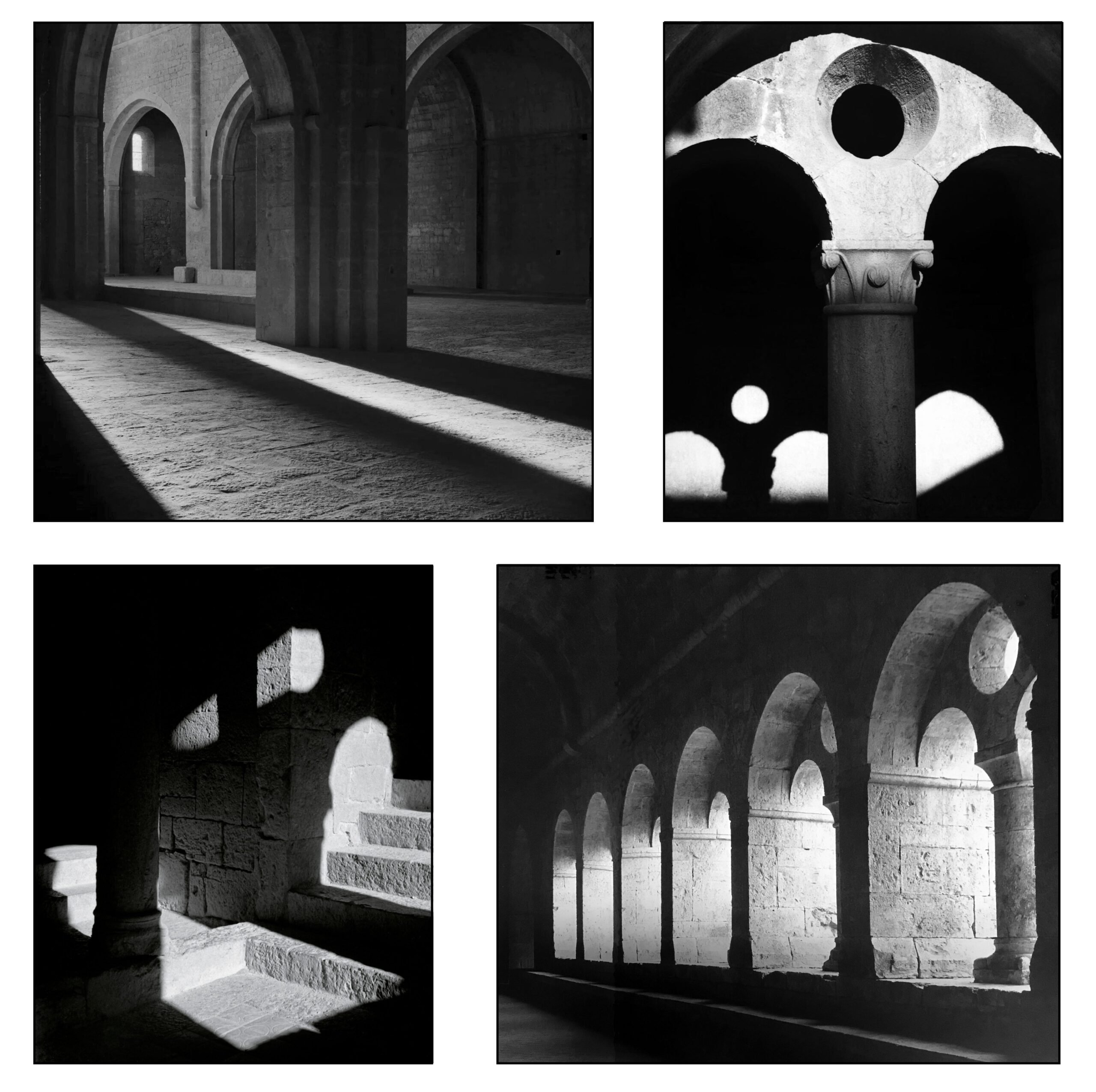

The early Cistercian abbeys built following these directives have a simplicity that appeals strongly to modern sensibilities. The architecture is one where the space is defined by light and where the acoustic is highly reverberant. The following is from John Pawson’s afterword to Lucien Hervé’s 2001 book on Le Thoronet called The Architecture of Truth:

The abbey offers a sublime example of what happens when gratuitous visual distraction is removed. The intrinsic beauty of materials is revealed; one sees with incredible clarity. Where there is embellishment — an enriched moulding, a carved capital —every detail is graphically registered. Light also finds its perfect context. Great shards of light carve out spaces in the interior, pools spill across tiled floors and finer, but no less dramatic. threads of light catch in mouldings, tracing semicircular arches, making them appear to be carved not out of stone but etched in solid luminescence. This light is more than a beautiful effect. It symbolizes the physical presence of the divine and it directs attention. In the morning, light is introduced into the church so that one’s gaze is drawn always forward, to the curved apse and the altar within it. ‘The soul must seek light,’ observed St Bernard, ‘by following light’. The designer of Le Thoronet (a man of whom, sadly, we know nothing) was shaping more than stones and vaults – he was reinforcing a code of behaviour, confirming a habit of contemplation. Further evidence of this is to be found in the acoustics of the church. A Cistercian monk passes most of each day in silence. The times when he does utter acquire extra significance in consequence. The acoustics at Le Thoronet, with its extraordinarily protracted reverberation, dictates a particular style and discipline of singing. Singers must sing slowly and in perfect unison. Comply, and the effect is ethereally beautiful. Deviate only a little in either respect, and the consequence is acoustic chaos.

And the following illustration shows some of Hervé’s photographs:

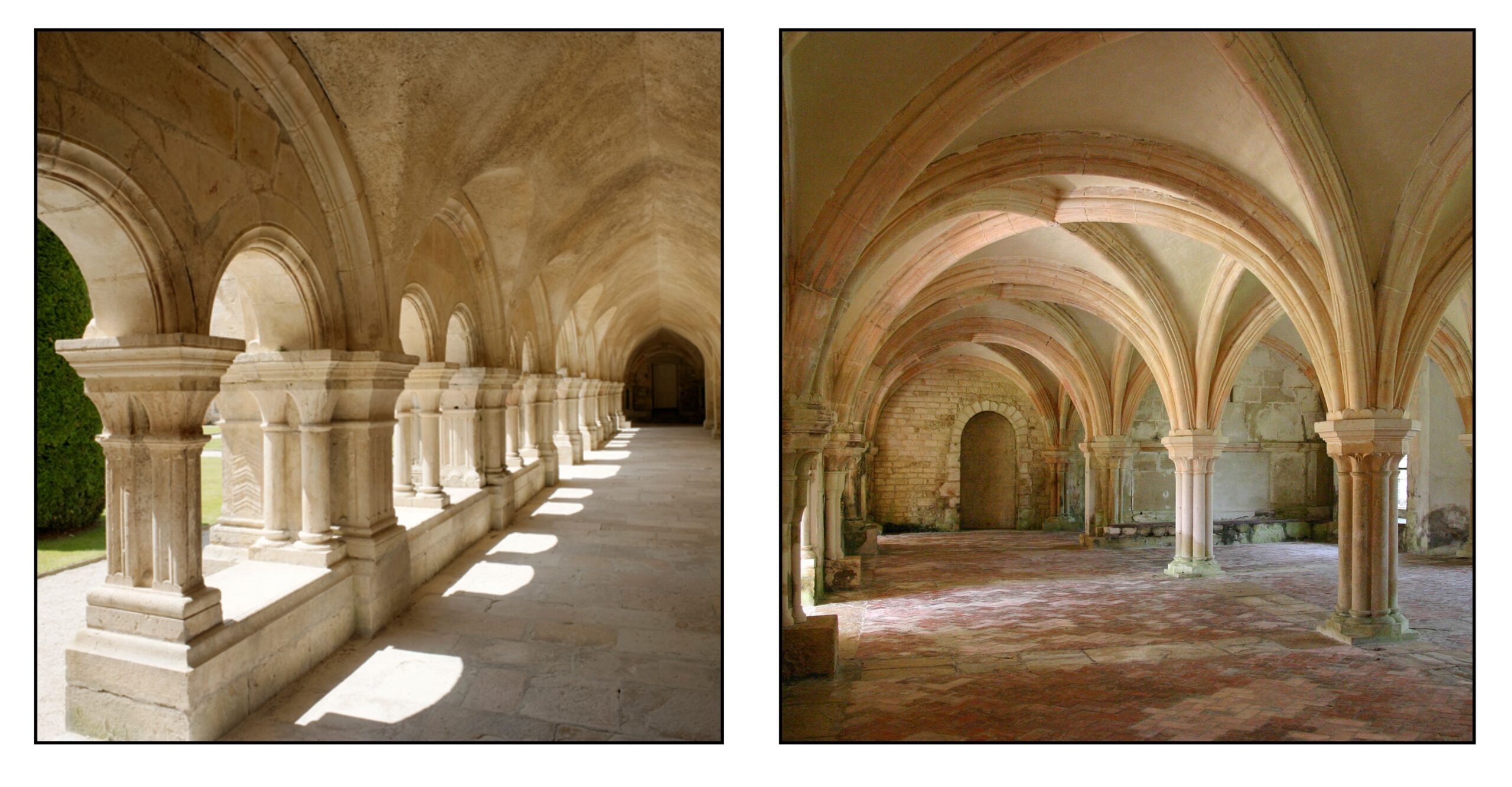

The prohibition of unnecessary decoration was not absolute, and the stone masons often provided simple non-figurative carvings on the capitula of the columns, as shown in the cloister of Sénanque, a sister abbey to Le Thoronet:

Central to the life of the monastery is the cloister (Latin claustrum, enclosure), a covered walkway surrounding a quadrangular or trapezoidal central space or “garth,” closed and separated from the external world (Brooke, 2003). Cloisters originated in the 8th Century in Europe when monasteries began to interact with the rest of society and felt the need to separate their monks from the outside world (Horn, 1973). Earlier monasteries, which had been built far from civilization and did not use lay brothers, had covered arcades, but these were not closed off from the world. The following illustration shows the cloister and chapter house at the Abbey of Fontenay in Burgundy.

In northern abbeys the cloister was typically nestled in the southern wall of the east-facing church so as to give the monks the benefit of the sunshine in winter. In some southern abbeys such as Le Thoronet the cloister is to the north so that the monks could find shade in the summer.

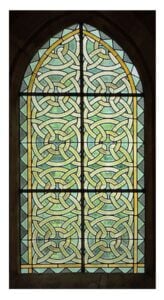

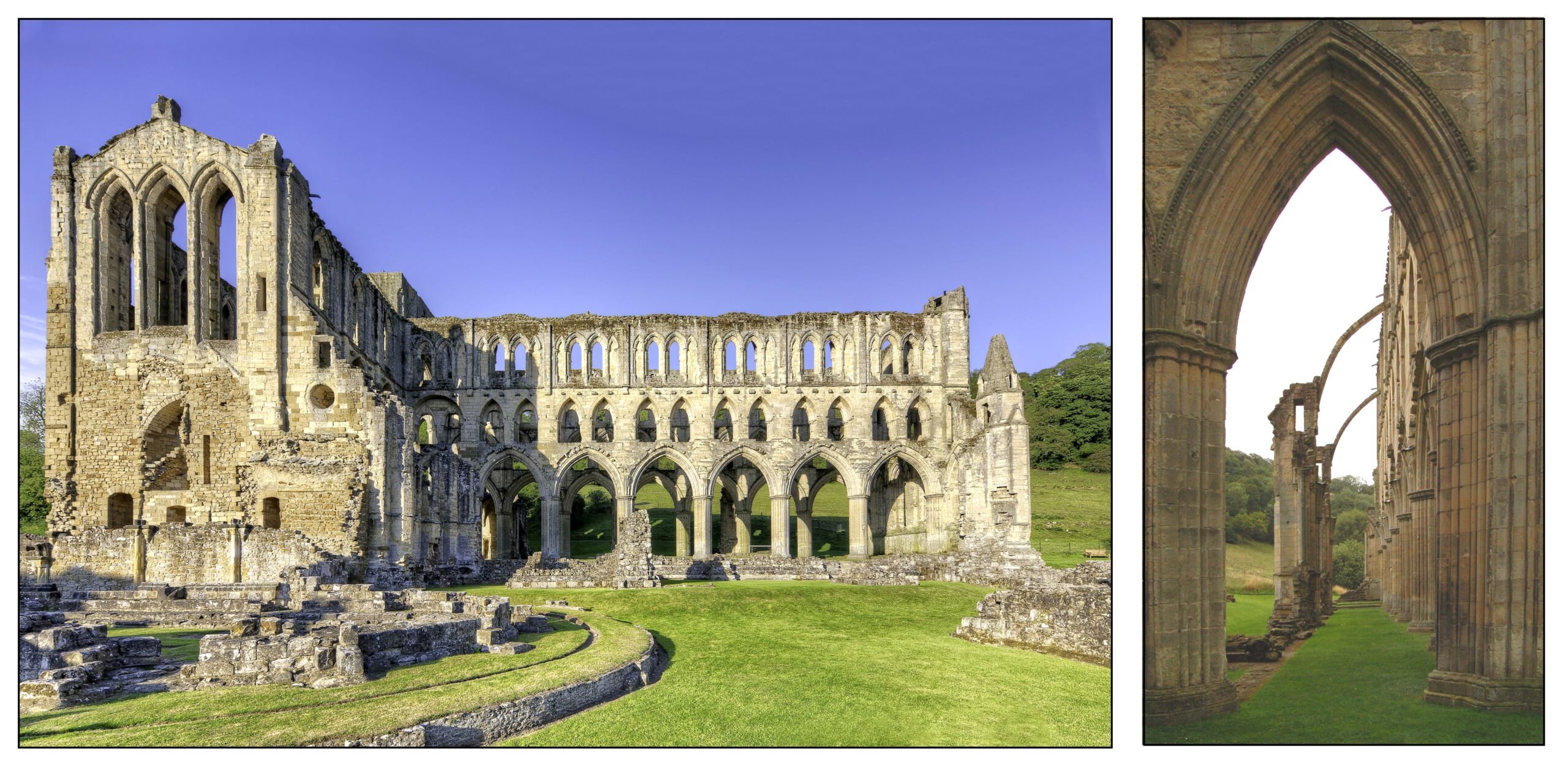

The earliest Cistercian buildings followed the general precepts of Romanesque architecture, with the exception that decoration was minimized. The ideas of Gothic architecture were worked out in the mid 12th-Century, particularly at the Benedictine Abbey Saint Denis just north of Paris. This style of architecture with its ribbed vaulting, flying buttresses, pointed arches and stained-glass windows soon spread across Europe. The Cistercians accepted many of these changes and some of their abbeys are beautiful examples of the Gothic style (as illustrated by the two views of the ruins of Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire shown below: the presbytery from the south, and the flying buttresses on the north side of the presbytery). However, the Cistercians still followed their principles of restraint: the abbey walls remained bare, and the glass windows were geometric and almost monochromatic (as illustrated in the restored window at Fontenay Abbey shown on the right). Designs in shades of light green (verdaille) were characteristic of Cistercian windows.

Economy

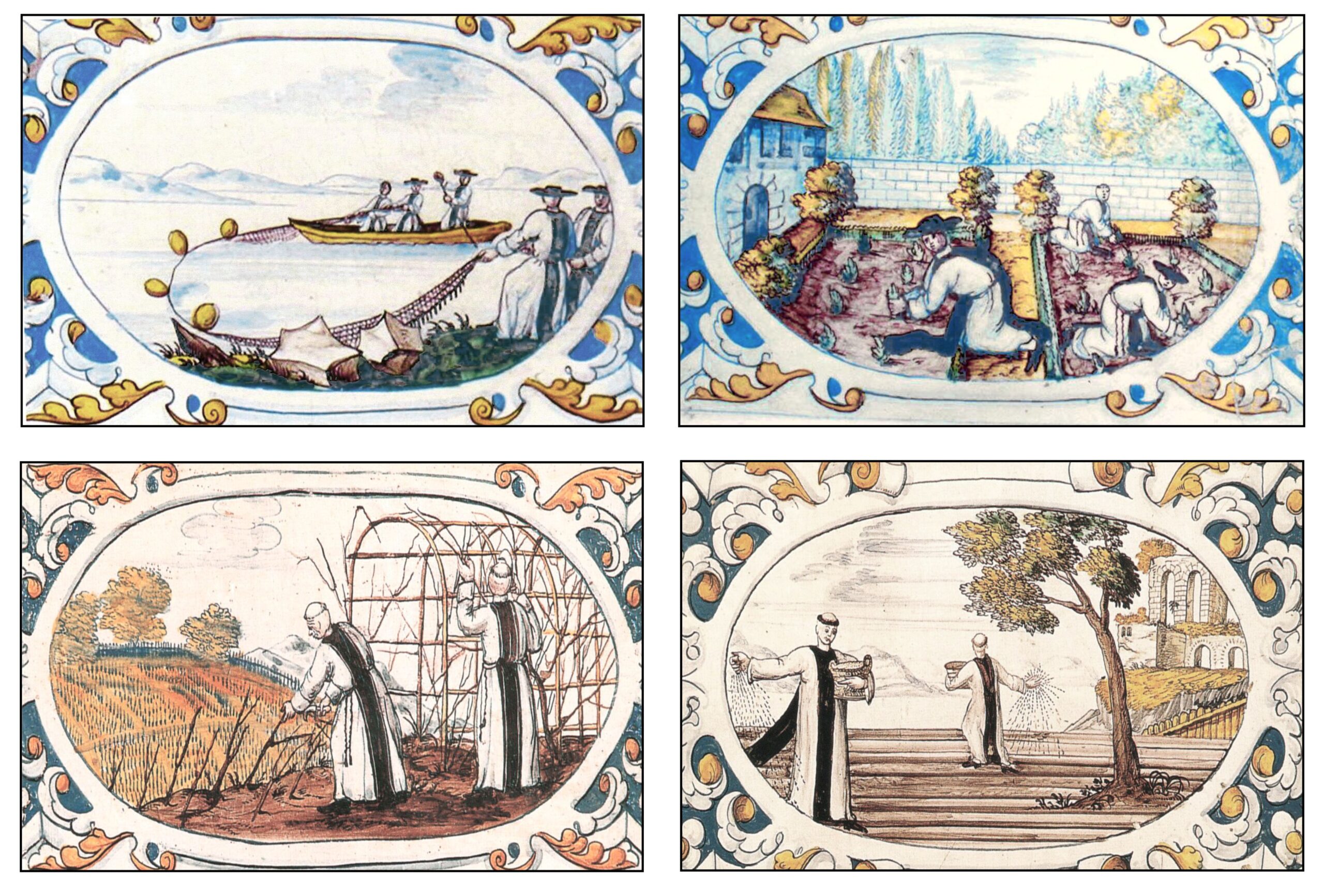

The Cistercians followed the rule of Saint Benedict which required that all the monks participate in manual labor. The monks divided their time between singing psalms, copy manuscripts and actual work in the abbey holdings. Their labor is illustrated on the tiles painted by Daniel Meyer in 1733 for a stove in Salem Abbey in southern Germany.

However, the Cistercians soon controlled estates far larger than could be taken care of by monks alone. More than in other monastic orders, Cistercians used lay-brothers to work the land, and over time the monks largely retreated to being managers rather than manual laborers.

In order to manage their extensive agricultural holdings, the Cistercians set up multiple small communities of lay-brothers each centered around a central “grange” or storage barn. The following illustration shows front and side views of the Cistercian Grange de Vaulerent (val de Laurent), which was built in 1220 by the monks at the Abbey of Chaalis in Northeastern France. The grange, which is 72 m long and 25 m wide, is still in use. The large square door on the left of the façade was added in the late 18th Century. The tower at the front contained a circular staircase that ascended to the quarters of the lay brother who managed the grange (Tobin,1995, p 41).

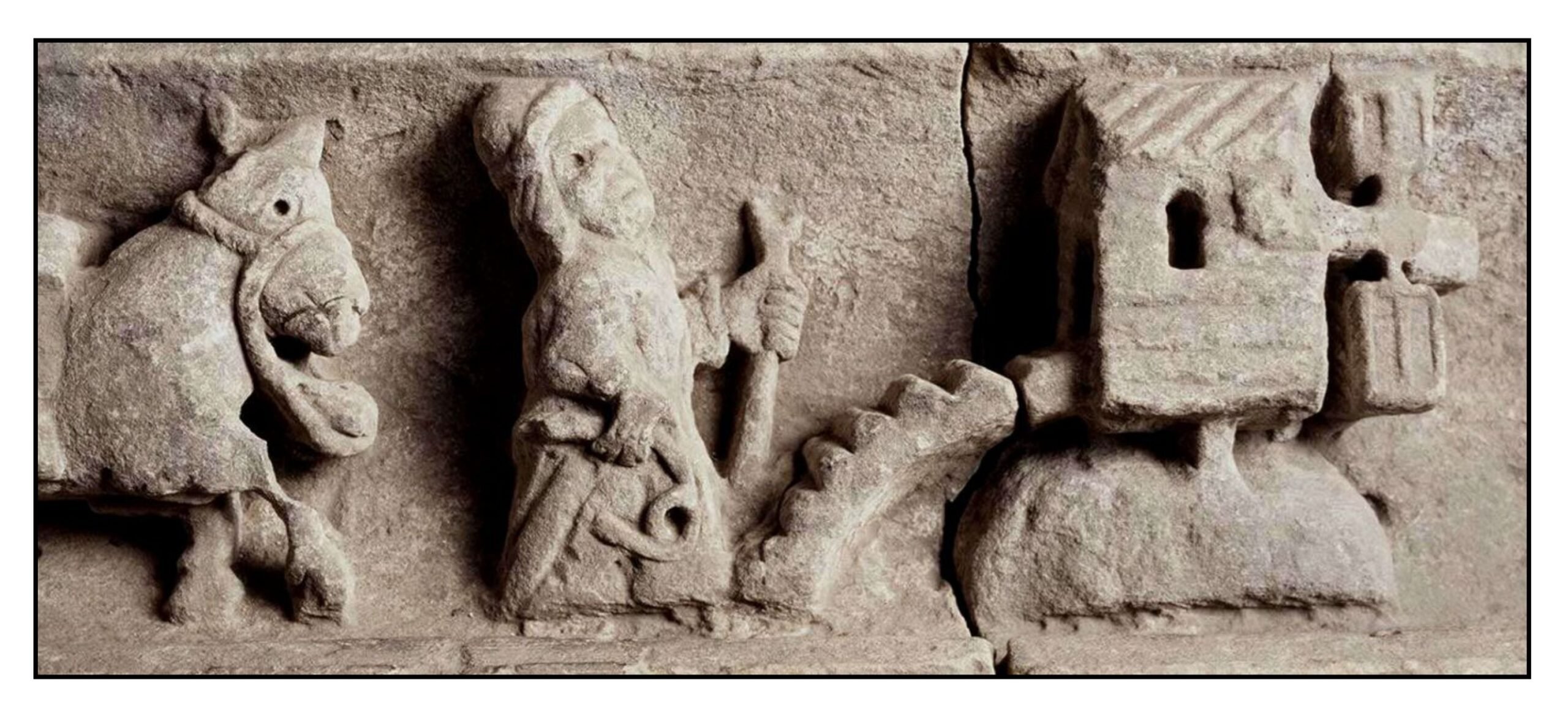

The Cistercians took advantage of the developing medieval technology. Their location on rivers and streams allowed the to use water power for milling grain. They also participated in the growing use of windmills. The illustration below from the frieze in the Rievaulx shows a farmer bringing a donkey laden with grain to a post-mill – one that was able to rotate as the wind changed its direction.

The Cistercians took advantage of the developing medieval technology. Their location on rivers and streams allowed the to use water power for milling grain. They also participated in the growing use of windmills. The illustration below from the frieze in the Rievaulx shows a farmer bringing a donkey laden with grain to a post-mill – one that was able to rotate as the wind changed its direction.

Most monks operated their own forges for metalwork. By the time of their dissolution by Henry VIII in the 16th Century, the monks at Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire apparently also had a functioning blast-furnace for smelting iron – over two centuries before the Industrial Revolution. (McDonnell, 1999).

The monks created their own kilns. These provided them with tiles for the floor, glass for the windows, and tableware for meals.

The following map (derived from information in Lekai, 1977) shows the Cistercian abbeys at the apogee of their European expansion (around 1500) and indicates the various industries in which the monks were involved. The Cistercians began to participate in the production of wine very early in their history – the Abbey of Cîteaux founded Clos de Vougeot, the largest Grand Cru vineyard on the Côtes de Nuits in 1115. The English abbeys became Medieval Europe’s the most important source of wool.

The economy of the Cistercians thus ensured that they were intricately related to the rest of medieval society. Maximilien Sternberg (2013, p 3) points out that their mode of existence was thus paradoxical:

On one hand, they sought salvation through a radical renunciation of the world. On the other hand, they were engaged in a dense web of relations with the very world they ‘renounced’. The white order effectively presented the culmination of this paradox of simultaneous withdrawal from, and engagement with, medieval society.

Bruun and Jamroziak (2013, p 3) also remark on “the tension between withdrawal and engagement, between the wilderness and the world”

In Retrospect

With the reformation of the early 16th Century the cistercian abbeys began their slow decline. In England, Henry VIII ordered the dissolution of the English monasteries in various directives from 1536 to 1541. His minister Thomas Cromwell had reviewed the abbeys and found them havens of superstition, idleness and undeserved luxury. After the dissolution, some of the English abbeys became parish churches or teaching colleges but most subsided into ruin. In continental europe the decline was for a while less abrupt. Then the French Revolution (1789-1799) ended most of the independent monasteries in France. Saint Bernard’s Abbey of Clairvaux was converted into a high-security prison.

The Cistercian Order persists though its numbers are much less than in the days of its success. At present it has two main divisions: the Cistercians of the Common Observance, and the Cistericans of the Strict Observance. The latter are also known as the Trappists, from their founding Abbey of La Trappe in Northern France.

Why did so many people flock to the Cistercian monasteries during their first three centuries? Monks clearly followed a spiritual calling. But why would a lay-brother join a monastery? Medieval life was hard and the monastic community provided accommodation and fellowship. Stephen Tobin (1995, p 45) suggests

Employment as a lay brother meant a guarantee of a roof over one’s head, a dry if somewhat uncomfortable bed, and two meals a day. In exchange for such otherwise unattainable security, all that was required of the lay brother was to work probably no harder than would have been necessary on his own or his feudal lord’s land, to attend church services perhaps a little more frequently, which can hardly have been much of a sacrifice in an age where belief in God was seldom questioned, and to forgo the company of women, which was possibly a little more taxing.

The main reason for the success of the Cistercians, however, was the promise of salvation. Aristocrats donated lands to the order with the tacit agreement that such donations would guarantee a place in heaven. The literate joined as monks because there was no other easy route to both knowledge and salvation. Peasants joined as lay-brothers so that they would be preferred in any judgement after death.

This link between vocation and salvation has been demonstrated in recent Catholic history. The Second Vatican Council in 1962 proposed that contrary to previous teaching, all Christians were called to holiness simply by being baptized and that those who pursued a religious vocation could no longer aspire to a superior state of holiness. This was followed by an immediate and catastrophic decline in the number of individuals taking religious vows (Stark & Fine, 2000, pp 169-190).

Nevertheless, the achievements of the Cistercians were impressive. They fostered new developments in agriculture and industry, developments that would not have happened so rapidly without the size of the Cistercian community. They built abbeys that are often considered the epitomes of spiritual architecture – places of respite from the suffering of the world, and homes where the search for truth could be followed. They established a style of life that some still long for. Many of us might yearn to grow lavender and tend to the honey-bees at a place like the Abbey of Sénanque (below) Almost everyone desires respite from the world – some for a lifetime and some only for brief periods. One hopes that the abbeys be preserved as places for quiet thought, independent of any dogmatic belief.

References

Berman, C. H. (2010). The Cistercian evolution the invention of a religious order in twelfth-century Europe. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Berman, C. H. (2013). Agriculture and economies. In Bruun, M. B. (Ed). The Cambridge companion to the Cistercian order. (pp 112-124) Cambridge University Press.

Brooke, C. N. L. (2003). The age of the cloister: the story of monastic life in the Middle Ages. Hidden Spring.

Bruun, M. B. (Ed.) (2013). The Cambridge companion to the Cistercian order. Cambridge University Press.

Bruun, M. B., & Jamroziak, E. (2013). Introduction: withdrawal and engagement. In Bruun, M. B. (Ed). The Cambridge companion to the Cistercian order. (pp 1-22) Cambridge University Press.

Coppack, G. (2000). The white monks: the Cistercians in Britain, 1128-1540. Tempus.

Coomans, T. (2013). Cistercian architecture or architecture of the Cistercians? In Bruun, M. B. (Ed). The Cambridge companion to the Cistercian order. (pp 151-169). Cambridge University Press.

Davis, S. J. (2018). Monasticism: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Donkin, R. A. (1978). The Cistercians: studies in the geography of medieval England and Wales. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies (University of Toronto).

Duby, G. (1983). L’art cistercien. Flammarion.

Dunn, M. (2007). The emergence of monasticism from the Desert Fathers to the early Middle Ages. John Wiley & Sons

Gaud, H., & Leroux-Dhuys, J.-F. (1998). Cistercian abbeys: history and architecture. H. F. Ullmann.

Hervé, L. (2001). Architecture of truth: the Cistercian Abbey of Le Thoronet. Phaidon Press (initially published in 1957)

Holdswoth, C. (2013). Bernard of Clairvaux: his first and greatest miracle was himself. In Bruun, M. B. (Ed). The Cambridge companion to the Cistercian order. (pp 173-185) Cambridge University Press.

Horn, W. (1973). On the origins of the Medieval cloister. Gesta, 2, 13–52.

Jamroziak, E. (2016). The Cistercian Order in Medieval Europe: 1090-1500. Routledge.

Lekai, L. J. (1977). The Cistercians: ideals and reality. Kent State University Press.

McDonnell, G. (Summer, 1999). Monks and miners: the iron industry of Bilsdale and Rievaulx Abbey. Medieval Life. pp 16-21.

Merton, T. (1960). The wisdom of the desert: sayings from the Desert Fathers of the Fourth Century. New Directions.

Merton, T., & O’Connell, P. F. (2015). Charter, customs, and constitutions of the Cistercians : Initiation into the monastic tradition 7. Cistercian Publications/Liturgical Press.

Pouillon, F. (1964). Les pierres sauvages: roman. Édition du Seuil; translated by Gillott, E. (1970). The Stones of the Abbay, Jonathan Cape

Reilly, D. J. (2018). The Cistercian reform and the art of the book in twelfth-century France. Amsterdam University Press.

Stark, R., & Finke, R. (2000). Acts of faith explaining the human side of religion. University of California Press.

Sternberg, M. (2013). Cistercian Architecture and Medieval Society. Brill.

Thornton, J. F. & Varenne, S. B. (2007). Honey and Salt: Selected spiritual writings of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux. Vintage.

Tobin, S. (1995). The Cistercians: monks and monasteries of Europe. Herbert Press.

Wortley, J. (2019). An introduction to the Desert Fathers. Cambridge University Press.