Searching for the Dao

This post presents some ideas about the Dào (“Way”) as described in the Dàodéjīng (“Book of the Way and its Virtue”), that legend claims was composed by Lǎozī in the 5th Century BCE. The Dào cannot be explained in words. But that has never stopped anyone from writing about it.

An Incident at Hangu Pass

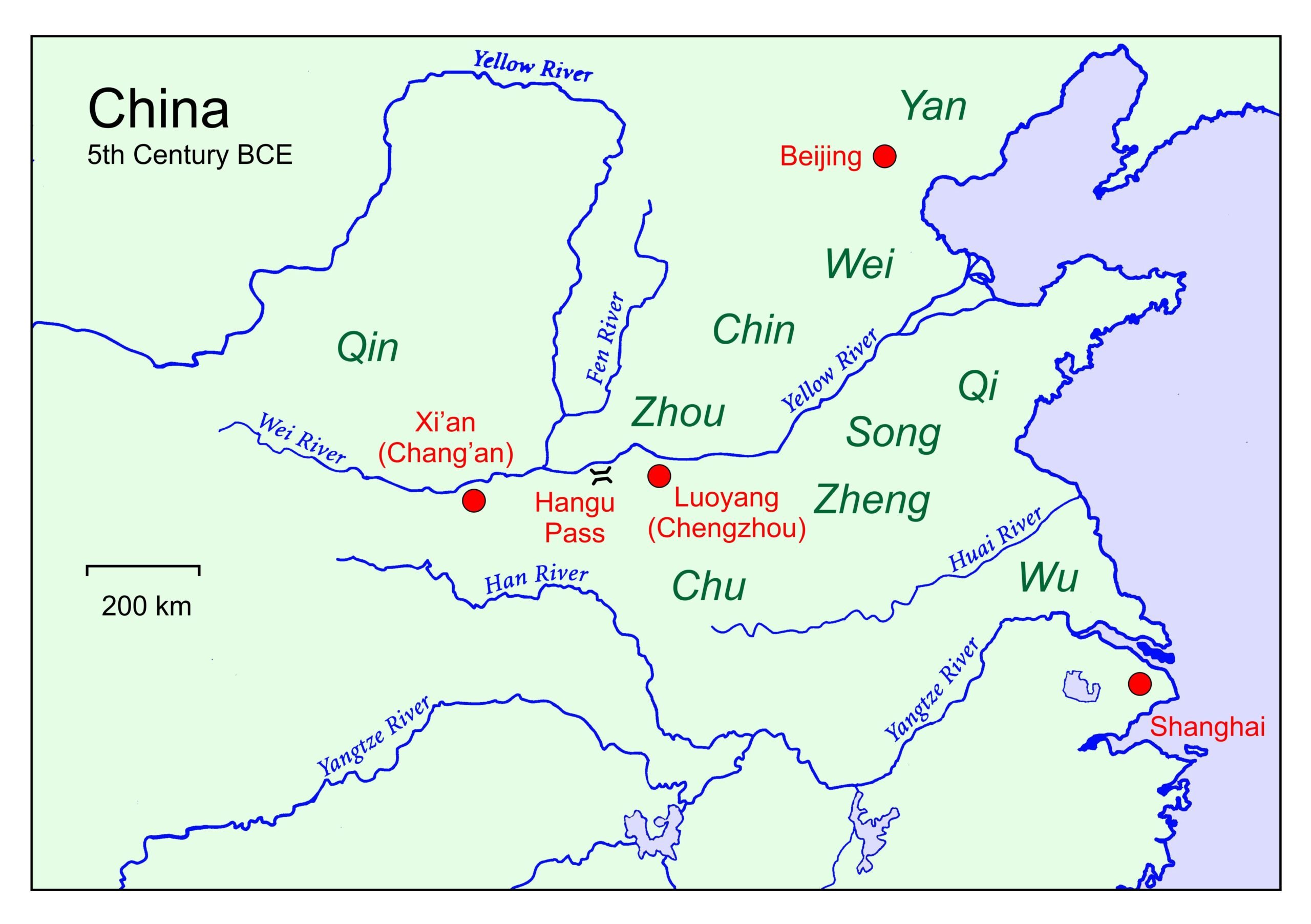

No one is sure of the season or even the year. It was probably at the end of the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BCE), and it would have been appropriate if it were autumn. An old man riding on a water buffalo, together with a young servant, requested passage to the west through the frontier gate at Hangu. They were leaving the violence and corruption of the Kingdom of the Eastern Zhou, which was slowly dissolving into anarchy, a time that was later historians called the Warring States Period (475-221 BCE).

Yĭnxĭ, the head guardsman, realized that the old man was of some importance. In answer to his questions, the old man confirmed that he had been the Royal Archivist at the court of Zhou. He had resigned his position, and was now on his way to the mountains to find peace. Yĭnxĭ requested that the old man not leave without providing him with a summary of his wisdom. The scholar obliged and wrote out a summary of all that he considered important. And then he departed, never to be heard of again.

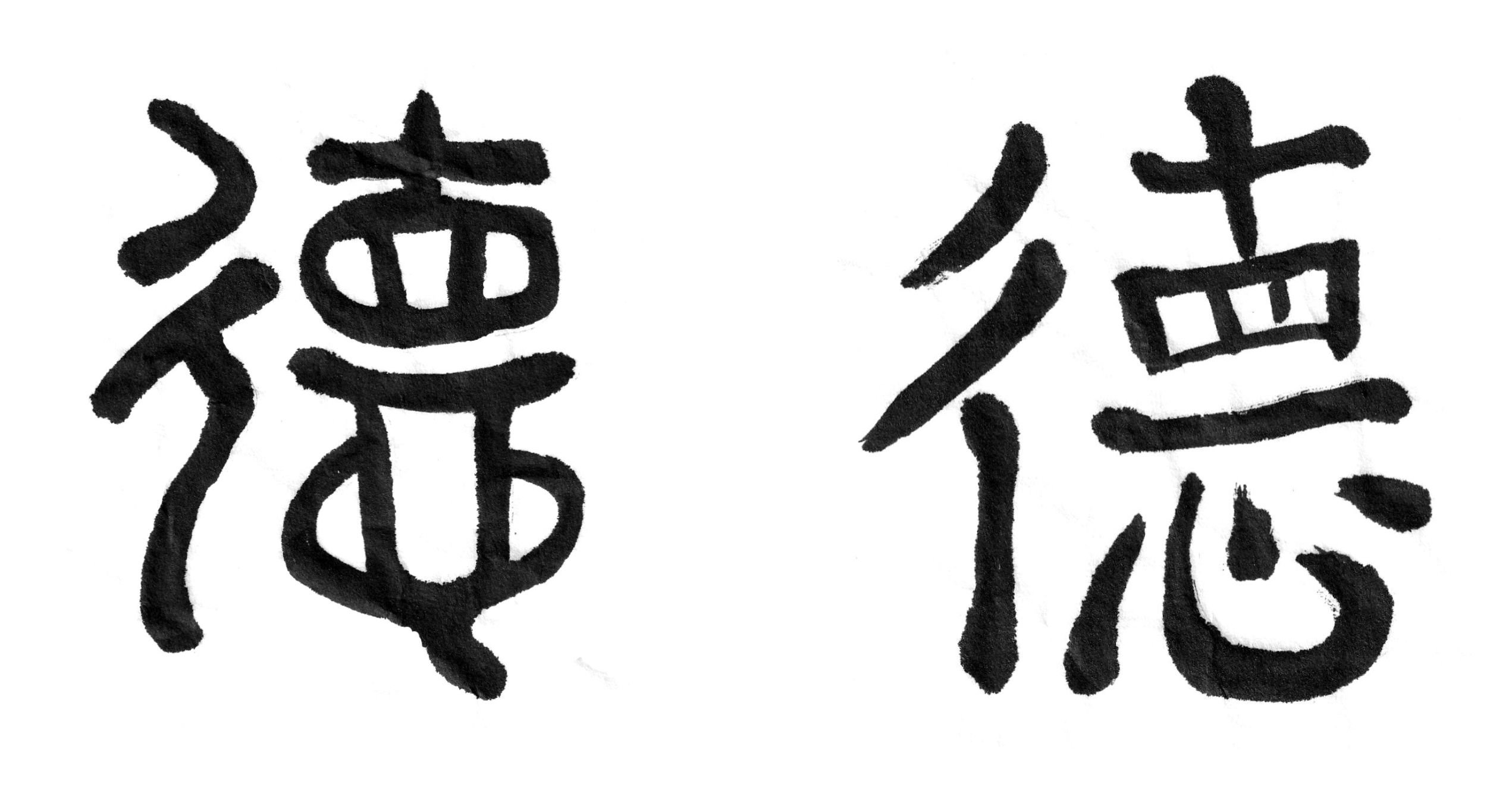

The writings that he left with Yĭnxĭ became known as the Dàodéjīng – the “Book of the Way and its Virtue” (Tao Te Ching in the old Wade-Giles system of romanization), containing about 5000 characters in 81 brief chapters. The first section of the book (chapters 1-37) dealt with the Dào (“way”), and the second section with Dé (“virtue”). The author became known as Lǎozī – the “Old Master” (Lao Tzu in Wade-Giles). Sometimes the book itself is also referred to as Lǎozī.

I have told the story as best I can. There are several legends about what happened, and I am not sure which are true, or even whether Lǎozī was an actual person (Graham, 1998; Chan, 2000). The story does explain the nature of the book – an anthology of cryptic sayings and opinions on the nature of the universe and how people should behave.

The Eastern Zhou dynasty had its court in Chengzhou, now called Luoyáng. From there the king tried to maintain his rule over the surrounding feudal states. After many years of internecine warfare, the Qin state in the west ultimately prevailed over the others and founded the first Chinese Empire in 221 BCE.

The frontier gate in the Hangu Pass has been preserved as the centerpiece of an archeological site in Xin’an:

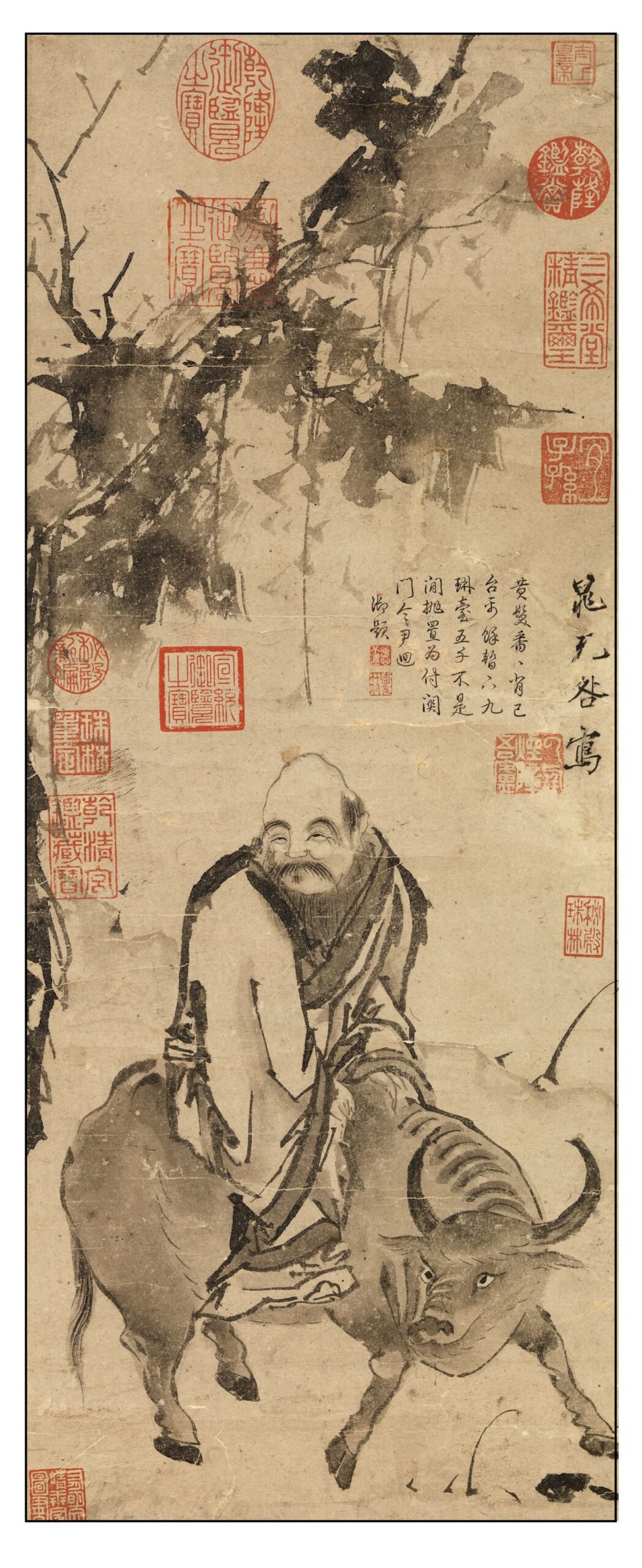

Lǎozī on his water buffalo was portrayed by Chao Buzhi in an ink painting (around 1100 CE) now in the Palace Museum in Taipei:

A carved jade circle from the early 19th Century represents the meeting between Lǎozī (right) and Yĭnxĭ (left) with the Hangu Gate at the top.

In 1938, Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) felt definite empathy for Lǎozī. He was living in Denmark, an exile from his home in Germany, which was descending into the horrors of Nazism. He wrote a poem The Legend of How the Tao te Ching Came into Being on Lao Tse’s Journey into Exile, which was later published in Tales from the Calendar (1949, translated 1961). The custom’s officer asks the boy attending on Lǎozī what he has learned from the old man and receives the answer

… Daß das weiche Wasser in Bewegung

Mit der Zeit den harten Stein besiegt.

[That over time the gentlest water

Defeats the hardest stone]

This paraphrases some lines from chapter 78 of the Dàodéjīng

Brecht ends his poem with

Aber rühmen wir nicht nur den Weisen Dessen Name auf dem Buche prangt! Denn man muß dem Weisen seine Weisheit erst entreißen. Darum sei der Zöllner auch bedankt: Er hat sie ihm abverlangt.

[But we should not just praise the Sage

Whose name is displayed on the book.

Since we must retrieve from the Wise their wisdom,

The customs officer should also be thanked

For demanding it of him.]

The Nature of the Dào

The main focus of Lǎozī ’s book is the Dào (pinyin, Tao in Wade-Gilles). The character is composed of the “walk/march” radical on the left (a leg taking a step forward) and the “head/chief” radical on the upper right (a head with hair or horns above a stylized face). The illustration below shows the Small Seal Script version (which would have been used at the beginning of the Qin dynasty) on the left, and the modern version on the right.

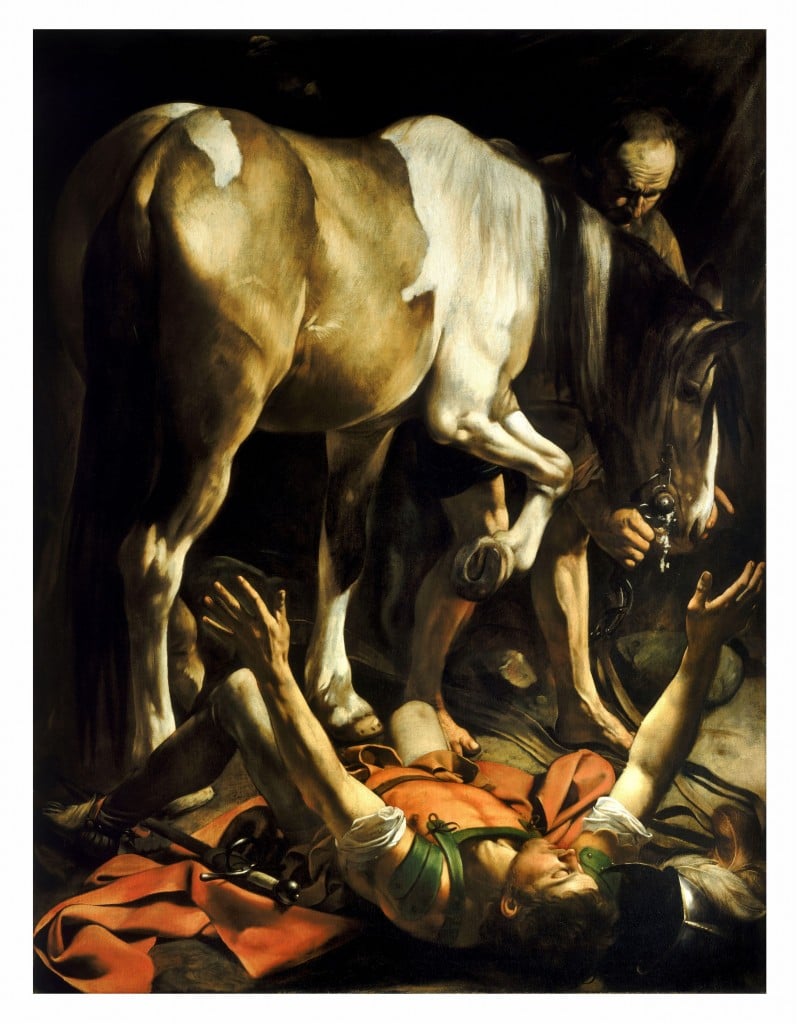

As a noun, Dào is most often translated as “way” or “path.” When it is used as a verb it generally means “say” or “explain.” This confluence of “way” and “word” also occurs in the Christian gospel of John (1:1, and 14:6), where the source of everything is called the word (logos) and salvation is obtained through the way (odos) (Ching, 1993, p. 88).

In Lǎozī ’s book, the Dào represents the underlying and enduring principle of the universe, something completely beyond human comprehension (Schwartz, 2000):

The Dào that can be explained is not the eternal Dào;

The Name that can be told is not the eternal Name.

The nameless is the source of heaven and earth,

The mother of everything which can be named.

Free from desire, you can realize its mystery;

Caught in desire, you see only its manifestations.

That these two aspects are both same and different

Is the paradox:

Mystery of mystery,

Gateway to wonder.

[Chapter 1, my translation. I am indebted to Mitchell (1988) for the opposition of “mystery” and “manifestations.” And to Pepper and Wang (2021) for their word-by-word analysis.]

Livia Kohn (2020, p 16) proposed:

One way to think of Dào is as two concentric circles, a smaller one in the center and a larger on the periphery. The dense, smaller circle in the center is Dào at the root of creative change— tight, concentrated, intense, and ultimately unknowable, ineffable, and beyond conscious or sensory human attainment… The larger circle at the periphery is Dào as it appears in the world, the patterned cycle of life and visible nature. Here we can see Dào as it comes and goes, rises and sets, rains and shines, lightens and darkens— the everchanging yet everlasting, cyclical alteration of natural patterns, life and death… This is Dào as natural transformations: the metamorphoses of insects, ways of bodily dissolution, and the inevitable entropy of life. This natural, tangible Dào is what people can study and learn to create harmony in the world; the cosmic, ineffable Dào, on the other hand, they need to open to by resting in clarity and stillness to find true authenticity in living.

Her description fits with that in Chapter 11 of the Dàodéjīng:

Thirty spokes converge on the wheel’s hub,

The emptiness of which allows the cart to be used.

And perhaps point to Eliot’s image in Burnt Norton (1941)

At the still point of the turning world. Neither flesh nor fleshless;

Neither from nor towards; at the still point, there the dance is,

But neither arrest nor movement.

As pointed out by Kenner (1959, pp 297-8))

This is the philosophers’ paradox of the Wheel, the exact center of which is precisely motionless, whatever the velocity of the rim.

Yīn and Yáng

The Dào is the source of all the different things in the word. The multiplicity of the world is described in Chapter 2 of the Dàodéjīng (translation by Ursula Le Guin, 1997):

For being and nonbeing

arise together;

hard and easy

compete with each other;

long and short

shape each other;

high and low

depend on each other;

note and voice

make music together;

before and after

follow each other.

The source of this multiplicity is proclaimed in Chapter 42 (my translation)

The Dào gives birth to one

One gives birth to two

Two give birth to three

Three gives birth to the myriad things of the world.

These carry Yīn on their back and Yáng in their arms

And together they achieve harmony

Yīn is water, earth, night, female; Yáng is fire, sky, day, male. Through much of the Dàodéjīng, Lǎozī is more partial to Yīn, the eternal female. Yīn and Yáng mix to form a third type of being and from this intermingling comes everything – Wànwù (ten thousand things). This process is depicted in the Tàijítú symbol: the outer circle represents the whole while the light and dark areas represent its opposing manifestations. The Tàijítú in turn becomes the center of the Bāguà (“eight symbols”) map, representing all the different elements of the world.

The Rule of Dé

The character for Dé (pinyin, Te in Wade-Giles) contains on the left the radical for “step/road.” The upper right of the character represents “truth” – something placed on a pedestal to be examined. The lower right is the radical for “heart.” The character thus embodies the idea of following the path of the true heart. Dé is translated as “virtue” or “morality.” The illustration below shows the Small Seal Script version on the left and the modern version on the right.

According to Lǎozī, virtue is attained by behaving in harmony with the Dào. Exactly how one does this is not completely clear. When he wrote his book, Lǎozī had decided that he needed to retire from the world, and much of his thought espouses the concept of wéiwúwéi – “acting without acting.” He urged leaders not to interfere with the lives of their people and not to overburden them with taxes. He urged generals to exercise restraint and patience.

Acting in harmony with the Dào meansdoing things for the good of all rather than the benefit of one. Occasionally Lǎozī does recommend particular virtues. The following is from Chapter 67 of the Dàodéjīng:

I have three treasures

that I hold and protect:

first is compassion,

second is austerity

third is reluctance to excel.

Because I am kind I can be valiant,

Because I am frugal I can be generous

Because I am humble I can be a leader.

[My translation owes much to Red Pine (2004), from whom I took the names of the treasures. Other expressions derive from Pepper and Wang (2021).]

The Religion of Dàoism

In the 2nd Century CE, Zhāng Dàolíng was visited by the spirit of Lǎozī, and proclaimed himself the first “Celestial Master” of the Dào. (Ching, 1993; Hendrichke, 2000, Kohn 2020; Robinet, 1992; Wong, 1997). Dàoism became an organized religion. Lǎozī was deified. Various other sages and believers were raised to the rank of “Immortals.” The descendants of Zhang Dàoling have continued to lead the religion to the present day. Dàoism as a religion provided its adherents with rituals, prayers, scriptures, talismans, and divination. Some of the “austerity’ of Lǎozī was perhaps lost in the proliferating ceremonies.

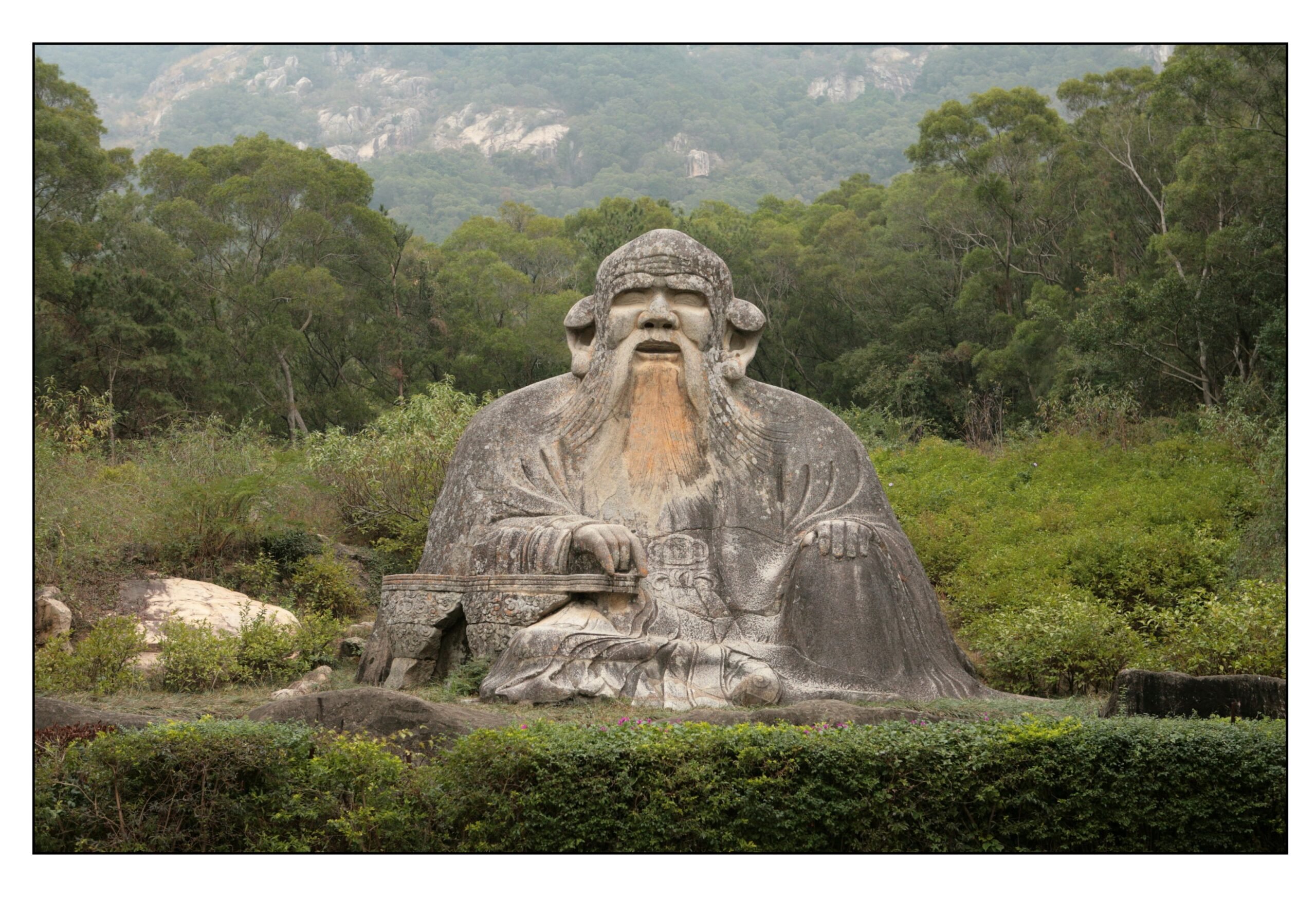

Dàoism was immensely popular. Temples sprang up everywhere. Dàoism was particularly attracted to the mountains, perhaps because this is where Lǎozī attained his immortality after leaving through Hangu Pass. Statues of Lǎozī and the immortals abound. The following is a large statue of Lǎozī created during the Song Dynasty (960-1279). It is located in the Qingyuan Mountain Park near Quanzhou city in Southern China.

The Art of Dàoism

Much of the art associated with Dàoism concerns the activities of the Immortals (Little, 2000; Little & Eichman, 2000). However, during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) when the Mongols controlled China and ruled an Empire that spread as far west as Europe, several artists evolved a style of landscape painting that attempted to portray the simple power of nature (Barnhart, 1983; Cahill, 1976; Scott, 2006).

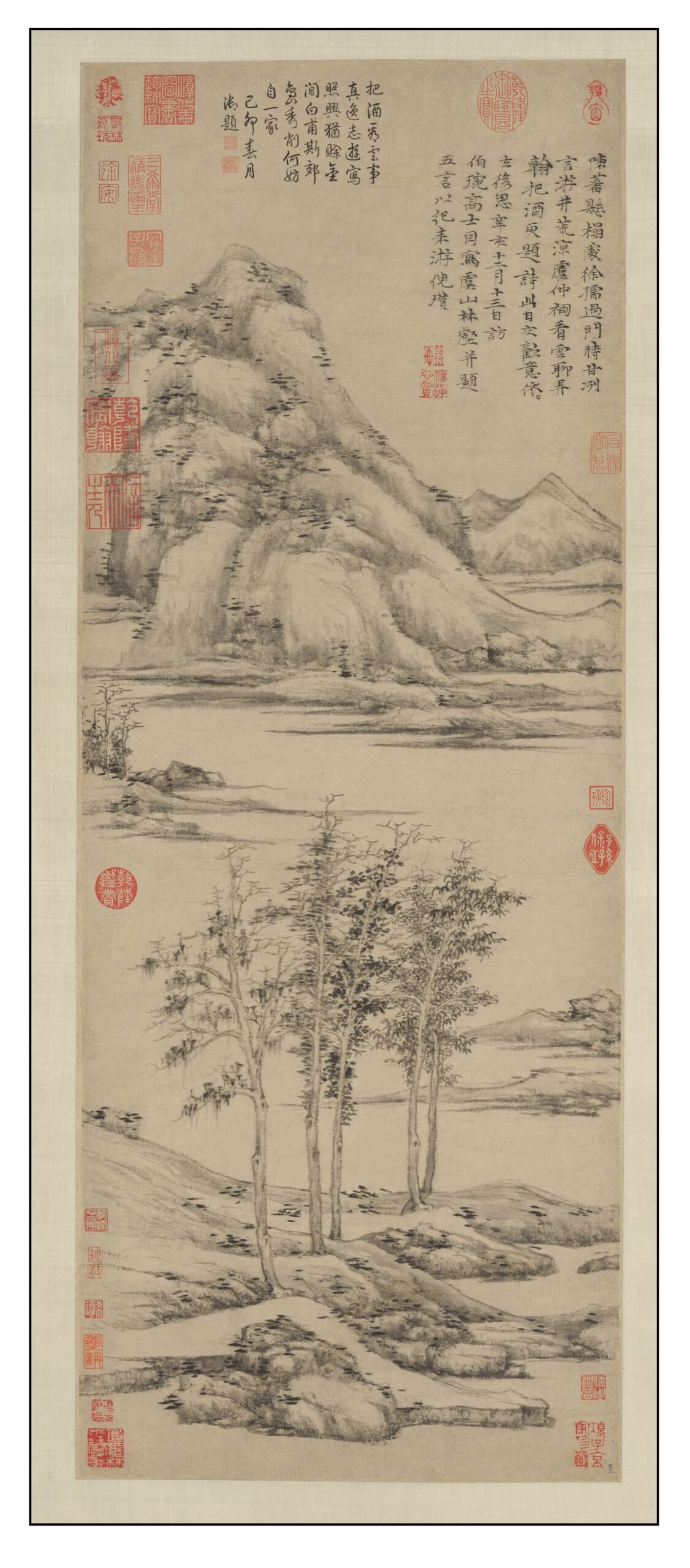

Probably the most famous of these painters was Ní Zàn (1301-1374), an aristocrat who gave up his worldly goods and retired from public life to live as an ascetic. One of his last paintings, now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, is entitled Woods and Valleys of Mount Yu (1372).

The poem appended to the top of the painting identifies where it was created and concludes:

We watch the clouds and apply our paint;

We drink wine and write poems.

The joyous feelings of this day

Will linger long after we have parted.

The painting portrays the stillness of the water in the lake and the power of the mountains on the further shore. These seem to embody the eternal forces of Yīn and Yáng. In the foreground are a few of the ten thousand things that make up our particular world. The most powerful part of the painting is that which is not painted – the water representing the force of Yīn.

The spirit at the center of all is called the dark female,

Gateway of the foundations of heaven and earth,

Which lasts unbroken and forever: use it.

[Dàodéjīng, Chapter 6, my translation]

Final Thoughts

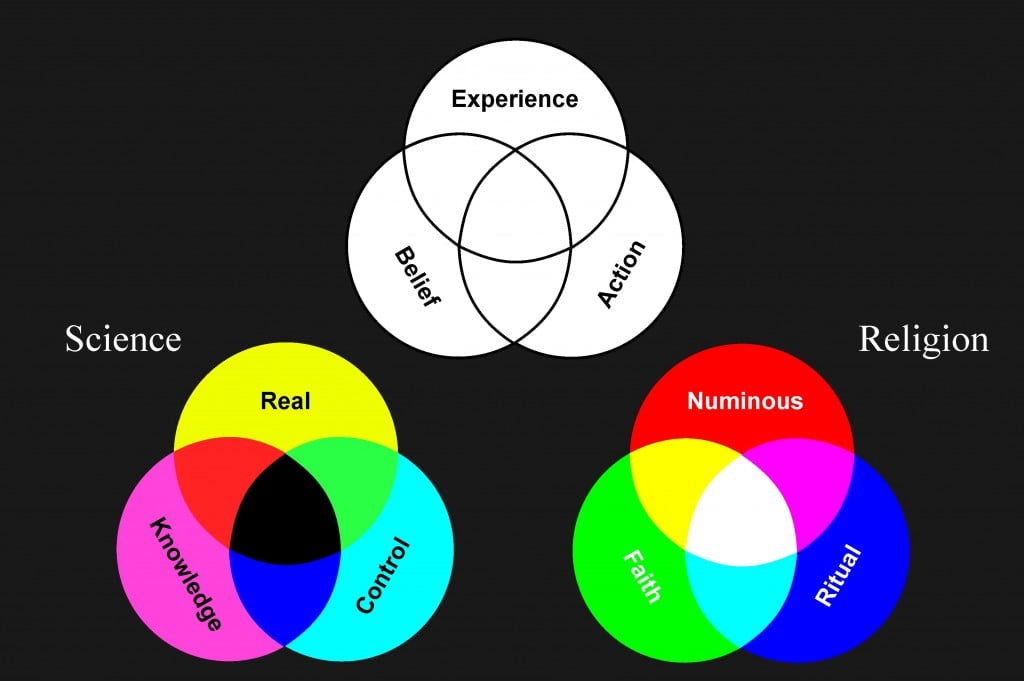

Most people believe that the universe is governed by rules. Many believe that such rules are purposeful and that the universe is evolving toward some goal. We are a hopeful species and we like to think of this process as benevolent rather than blind. Many of our religions urge us to fit our individual intentions to this more general goal. Of all this we are unsure. But there is something behind it all:

Something there is, whose veiled creation was

Before the earth or sky began to be;

So silent, so aloof and so alone,

It changes not, nor fails, but touches all:

Conceive it as the mother of the world.

I do not know its name;

A name for it is “Way.”

[Dàodéjīng, Chapter 25, Blakney (1955) translation]

Some Translations of the Dàodéjīng (in order of publication)

Julien, S. (1842). Le Livre de la Voie et de la Vertu. Imprimerie Royale

Chalmers, J. (1868). The Speculations on Metaphysics, Polity, and Morality of the “Old Philosopher” Lau-tsze. Trübner & Co.

Legge, J. (1891). The Tao Teh King, In Sacred Books of the East, Vol. XXXIX. Oxford University Press.

https://archive.org/details/wg939/page/n3/mode/2up

Waley, A. (1936). The way and its power: a study of the Tao tê ching and its place in Chinese thought. George Allen & Unwin.

Blakney, R. B. (1955). The way of life. A new translation of the Tao tê ching, New American Library.

Feng, G., & English, J. (1972). Tao te ching. Vintage Books. Third edition (2011) has introduction by J. Needleman and acknowledges T. Lippe as co-author.

Mitchell, S. (1988). Tao te ching. Harper & Row.

Addiss, S., & Lombardo, S. (1993). Tao te ching. Hackett.

Red Pine (1996, revised 2004), Lao-Tzu’s Taoteching with selected commentaries from the past 2000 years. Copper Canyon Press.

Le Guin, U. K., & Seaton, J. P. (1998). Tao te ching: a book about the way and the power of the way. Shambhala.

Star, J. (2001). Tao te ching: the definitive edition. Jeremy P Tarcher/Putnam.

Lin, D. (2015). Tao te ching: Annotated and explained. SkyLight Paths.

Minford, J. (2018). Tao te ching (Daodejing): The Tao and the power. Viking

Pepper, J.& Wang, X. H. (2021). Dao de jing in clear English including a step-by-step translation. Imagin8 Press.

References

Barnhart, R., & Wang, C. C. (1983). Along the border of heaven: Sung and Yüan paintings from the C.C. Wang family collection. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Brecht, B. (1949/1961). Tales from the calendar; the prose translated by Yvonne Kapp; the verse translated by Michael Hamburger. Methuen.

Cahill, J. (1976). Hills beyond a river: Chinese painting of the Yüan Dynasty, 1279-1368. Weatherhill.

Chan, A. K. L. (2000). The Daodejing and its tradition. In L. Kohn (Ed.) Daoism handbook. (pp.1-29). Brill

Ching, J. (1993). Chinese religions. Macmillan.

Eliot, T. S. (1941). Burnt Norton. Faber and Faber.

Graham, A.C. (1998). The origins of the legend of Lao Tan. In Kohn, L., & LaFargue, M. (eds). Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching. (pp 23-40). State University of New York Press.

Hendrichke, B. (2000). Early Daoist movements. In Kohn, L. (2000). Daoism handbook. (pp. 134-164). Brill.

Kenner, H. (1959). The invisible poet: T.S. Eliot. McDowell, Obolensky.

Kohn, L., & LaFargue, M. (1998). Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching. State University of New York Press.

Kohn, L. (2000). Daoism handbook. Brill.

Kohn, L. (2020). Daoism: a contemporary philosophical investigation. Routledge.

Little, S. (2000). Daoist Art. In L. Kohn (Ed.) Daoism handbook. (pp.709-746). Brill.

Little, S., & Eichman, S. (2000). Taoism and the arts of China. The Art Institute of Chicago

Robinet, I., (1992, translated by Brooks, P. (1997). Taoism: growth of a religion. Stanford University Press.

Schwartz, B. (1998). The Thought of the Tao te ching. In Kohn, L., & LaFargue, M. (eds.). Lao-tzu and the Tao-te-ching. (pp. 189-210). State University of New York Press.

Scott, S. C. (2006). Sacred Earth: Daoism as a preserver of environment in Chinese landscape painting from the Song through the Qing Dynasties. East-West Connections: Review of Asian Studies, 6(1), 72-98.

Wong, E. (1997). Taoism: an essential guide. Shambhala.