The Divine Feminine

All the major religions of the present world are androcentric in nature and misogynistic in practice. The following are some typical injunctions in the Christian scriptures:

Let your women keep silence in the churches: for it is not permitted unto them to speak; but they are commanded to be under obedience as also saith the law.

And if they will learn any thing, let them ask their husbands at home: for it is a shame for women to speak in the church. (I Corinthians 14: 34-35)

Let the woman learn in silence with all subjection.

But I suffer not a woman to teach, nor to usurp authority over the man, but to be in silence. (1 Timothy 2: 11-12)

These rulings are in spite of (or perhaps because of) women being more attentive to religious teachings, and participating more often in religious services than men (Pew Research Foundation, 2016). The two passages nevertheless serve a purpose – they provide clear evidence that the New Testament does not always represent the word of God.

The androcentricity of organized religion differs completely from prehistoric religious beliefs, wherein God was more likely female than male (Stone, 1978). Over recent centuries, however, female aspects of the godhead have become more and more recognized. This posting briefly considers some of the manifestations of the divine feminine, and mentions what might be involved in a feminist theology.

The Primordial Mother

In prehistoric families, the most amazing and incomprehensible event was the birth of a child. The role of the father was little understood, and mothers were revered as the primary source of this new life. A female force was therefore naturally thought to be behind the creation of the universe, and was worshipped as a mother goddess (Graves, 1948; Neumann, 1963; Stone, 1978). Between 30,000 and 10,000 years BCE, small votive offering to the mother goddess – “Venus figurines” – were created throughout Europe. The illustration below shows (from left to right) the ceramic Venus of Dolni Vestonice in the Czech Republic, the limestone Venus of Willendorf in Austria and the serpentine Venus of Savignano in Italy:

Barstow (1983) describes these figurines:

The goddess was faceless, as if to accentuate her universality, her ability to “stand for the power of the female. Lacking feet, she appeared to come straight up out of the earth, with which she was identified. Unclothed, her every body seem to have an efficacy. Often – but not always – she was big-breasted, and her hands were frequently placed under her breasts as if to display them. Many figurines show her entire body as ample, with huge breasts, belly and buttocks, as if the very plenitude of her body would ensure plentiful crops and hers. Sometimes she is pregnant, her enlarged belly emphasized by special markings.

In neolithic times, most societies began to worship multiple divinities, though female forces were among the most important – Ishtar in Mesopotamia, Astarte in Canaan, Persephone in Greece. and Isis in Egypt. These goddesses often displayed two aspects: one related to life and fertility and the other to death and war.

These goddesses were widely worshipped, with their followers often participating in extended rites called the “mysteries.” Apuleius’ Latin novel The Golden Ass (2nd Century CE) tells the story of Lucius who, while dabbling in the magic arts, inadvertently turned himself into an ass. At the end of the book, he attends one of the mysteries, and is changed back to human form through the power of Isis. The goddess announces herself:

I am here before you, Lucius, moved by your prayers—mother of the natural world, mistress of all the elements, firstborn offspring of the ages, highest of the deities, queen of the dead, first among the gods, the manifestation in a single body of all the gods and goddesses. I control by my will the luminous summits of the sky, the salubrious breezes of the sea, and the mournful silence of the underworld. I am the single divine being, worshipped the world over in different forms, with varying rites and under a multitude of names. Some call me Juno, others Bellona, some Hecate, and yet others Rhamnusia. But the people on both sides of Ethiopia who are lit by the first rays of the rising sun, and the Egyptians, pre-eminent for their ancient knowledge, worship me with the proper rituals and by my true name: Queen Isis. (Translation of Singer and Finkelpearl, 2021, pp 158-60)

The illustration below shows a pectoral ornament in the form of a winged Isis from the Museum of Fine Art in Boston. In her right hand, she holds an ankh, the symbol for “life”; in her left hand she holds what may be the hieroglyph for a sail, the symbol for the breath of life. On her head is a throne, indicating her majesty.

Judaism – Wisdom and Shekhinah

In the Hebrew scriptures Jahweh is most definitely male, and there is little mention of any female aspect to the deity. However, in Proverbs there are several passages spoken by the female figure of Wisdom (Hokhmah), one of which reads

I was set up from everlasting, from the beginning, or ever the earth was.

When there were no depths, I was brought forth; when there were no fountains abounding with water.

Before the mountains were settled, before the hills was I brought forth:

While as yet he had not made the earth, nor the fields, nor the highest part of the dust of the world.

When he prepared the heavens, I was there: when he set a compass upon the face of the depth:

When he established the clouds above: when he strengthened the fountains of the deep:

When he gave to the sea his decree, that the waters should not pass his commandment: when he appointed the foundations of the earth:

Then I was by him, as one brought up with him: and I was daily his delight, rejoicing always before him;

Rejoicing in the habitable part of his earth; and my delights were with the sons of men. (Proverbs, 8 22-31)

Christians have interpreted this passage as referring to Christ the Son, who they believe was with God the Father before the world began. Christ is described as “the power of God and the wisdom of God” in I Corinthians 1:24.

This female figure of Wisdom in Proverbs is closely associated with Sophia– the goddess of wisdom and the creator of the world in Gnostic scriptures (Perkins, 1985).

Wisdom also became related to the concept of the Shekhinah – God’s “presence” or “immanence” in the world. This concept was initially used to describe the holiness of the Ark of the Covenant, but expanded to include the idea of God’s dwelling with his people. Shekhinah is manifest when believers gather to study the Torah, celebrate the Sabbath, or pray together. The Mishnah (probably derived from Jewish oral tradition in the centuries BCE) states

If two sit together and there are words of Torah spoken between them, then the Shekhinah abides among them (Pirkei Avot, 3:2)

In the medieval period, the presence of God in the world was conceived as in terms of the ten Sephiroth of the Kabbalah. The tenth Sephirah is known either as Malkuth (“kingdom”) or Shekhinah (“presence”). In Kabbalistic writings the Shekhinah became the female aspect of the Godhead (Smith, 1985; Scholem, 1991; Devine, 2014; Laura, 2015).

In the Sefer ha-Zohar (13th Century CE), the Shekhinah is considered as the intermediary between God and his people:

Every message the King requires goes forth from this Lady’s house. Any message from below that is sent to the King arrives first at the house of His Lady, and from there proceeds to the King. The Lady is thus the universal go-between, from above to below and from below to above. (Zohar 2:51a quoted by Green, 2002).

Scholem (1965) describes the uneasy status of Shekhinah in Jewish religious thought:

This discovery of a feminine element in God, which the Kabbalists tried to justify by gnostic exegesis, is of course one of the most significant steps they took. Often regarded with the utmost misgiving by strictly Rabbinical, non-Kabbalistic Jews, often distorted into inoffensiveness by embarrassed Kabbalistic apologists, this mythical conception of the feminine principle of the Shekhinah as a providential guide of Creation achieved enormous popularity among the masses of the Jewish people, so showing that here the Kabbalists had uncovered one of the primordial religious impulses still latent in Judaism. (p. 105).

Christianity – Mother Mary

Mary, mother of Jesus, is not considered extensively in the Christian scriptures. Outside of five main episodes – the angelic annunciation of the forthcoming virgin birth, the visitation with Elizabeth, the nativity of Christ, presentation of Jesus in the temple, and the crucifixion, she is scarcely mentioned. In one brief episode she visited her son while he was teaching and was ignored (Mark 6: 31-34). However, Christ did acknowledge her at the crucifixion, telling John, “Behold thy Mother!” (John 19: 26-27).

Mary was not mentioned in the first version of the Nicene Creed of 325 CE, but acknowledged as the virgin mother of Christ in the revised version of the creed in 381 CE:

Jesus Christ …. who for us men, and for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Ghost and of the Virgin Mary, and was made man

Since Christ was both God and Man, his mother was special – Theotokos, the bearer of God. This was first pronounced at the council of Ephesus in 431 CE. Mary the mother of God has been long venerated in the Eastern churches. The illustration below shows the mosaic (9th Century CE) in the cathedral (now mosque) of the Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) in Constantinople, and the icon of Mary and the Infant Jesus of Vladimir (1131 CE).

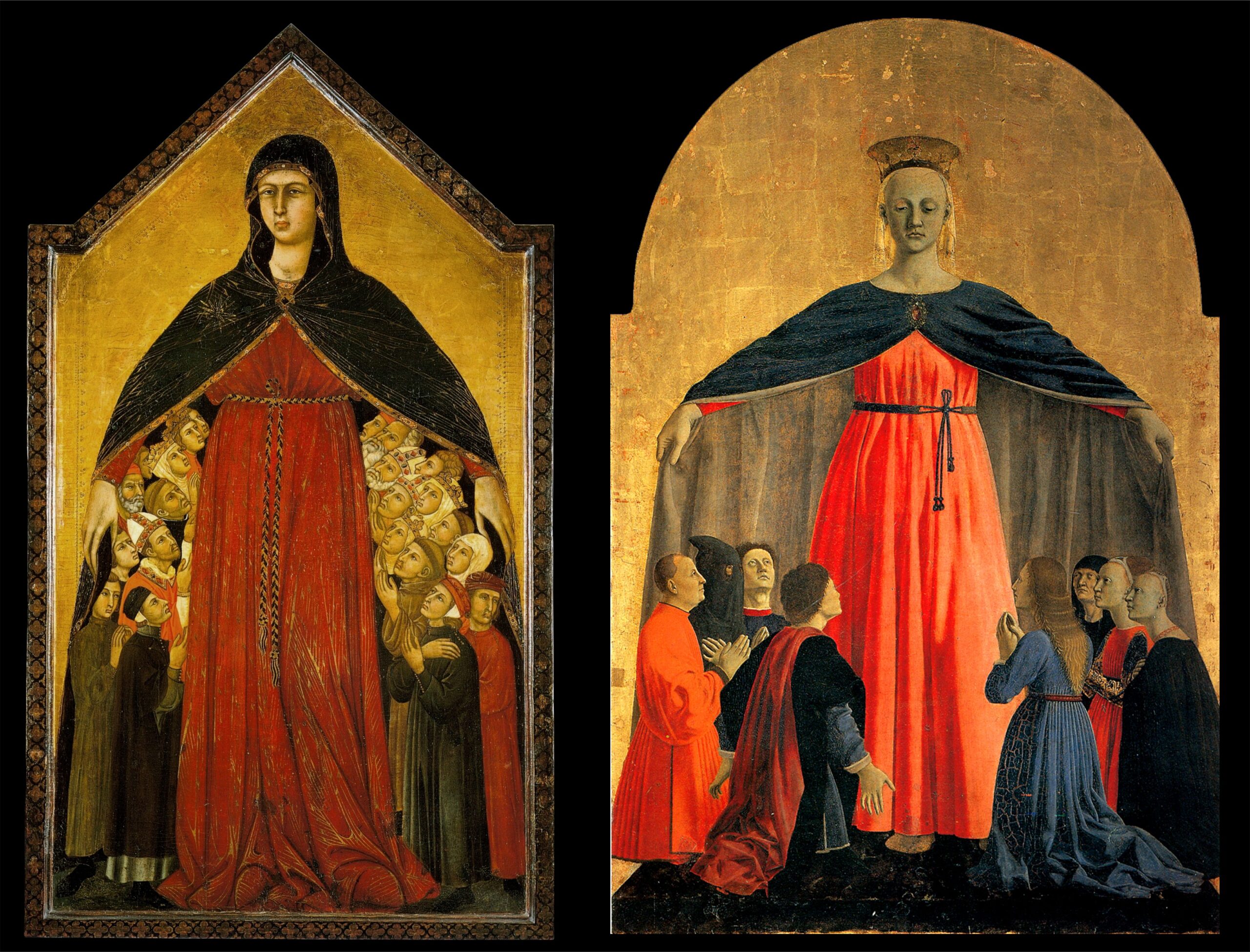

After the turn of the 1st Millennium CE, Mary began to be more and more honored in the Western Church. No one really understands this change in religious feeling. Most of the new Gothic Cathedrals in France were dedicated to Notre Dame (“our Lady”), and special Lady Chapels were built in English cathedrals. Believers thronged to images of Mary for consolation and for mercy. The following illustration shows two representations of the Madonna della Misericordia (“Lady of Mercy”), by Simone Martini (1310) and Piero della Francesca (1462).

Various traditions and beliefs have accumulated over the years so that now Marianism is an acknowledged subset of Christian beliefs, particularly in the Eastern and Roman Catholic Churches (Johnston, 1985; Leith, 2021; Matter, 1983; Rubin, 2009). In 1568 the Ave Maria was included in the Roman Catholic Breviary. The most famous setting of the prayer is by Gounod (1859) based on Bach’s Prelude No 1 (1722).

Ave Maria, gratia plena, Hail Mary, full of grace,

Dominus tecum the Lord is with thee

benedicta tu in mulieribus Blessed art thou amongst women,

et benedictus fructus ventris tuis, Jesu and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus.

Sancta Maria, Mater dei, Holy Mary, Mother of God,

ora pro nobis peccatoribus pray for us sinners,

nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. now and at the hour of our death.

Theologians have long argued that Mary must have been herself conceived without sin so that she might carry the incarnation of God within her womb. This doctrine of the “immaculate conception” was discussed for many years, but only finally accepted by the Vatican in 1854. Since Mary was without sin, there was no need for her to die. Theologians therefore proposed that before her death she was instead taken up directly into heaven – “the assumption of the Virgin.” This idea finally becoming Catholic doctrine in 1950. Protestants reject both these doctrines. When it comes to Mary, the Christian churches have been loathe to allow their members the beliefs they long for.

Hinduism

In contrast with the Western (or Abrahamic) religions, Hinduism is adorned with goddesses of many types and purposes (Kinsley, 1986; Pattanaik, 2000). Eroticism is an acknowledged part of divinity.

The supreme goddess Mahadevi is widely venerated. She changes form at will and goes by many names. She can exist alone as Shakti, the goddess of cosmic energy, or as Kali, the goddess of time and change. The illustration below shows a bronze statue of Bhudevi, the “Goddess of the Earth” (13th Century CE) from the Los Angeles Museum of Art

The female goddess often serves as the consort of a male divinity – Parvati with Shiva, and Lakshmi with Vishnu. Sometimes these pairs become unified into one deity – the androgynous Ardhanarishvara, whose right side is feminine and left side male. The illustration below shows a sandstone relief of Shiva and Parvati (11th Century CE) from the Dallas Museum of Art, and a bronze Ardhanarishvara (circa 1000 CE) from the Los Angeles Museum of Art.

Buddhism

Buddhism is often considered as a religion without the need for gods or goddesses. Since the universe has existed forever there is no need to postulate a divine force that once created it. However, the Buddha in his various manifestations and many of his enlightened followers (the Bodhisattvas, from bodhi, knowledge, and sattva, being) are revered as sincerely as any of the gods in more definitely theistic religions.

The Buddha and most of the Bodhisattvas are male. The hierarchy of priests and monks in Buddhism are male (Faure, 2008). However, over the centuries the feminine has made its appearance.

One of the most important of the Bodhisattvas was known as Avalokitasvara – “the lord (isvara) who gazes (lokita) down (ava) at the world.” This Bodhisattva of Compassion is described as the “Regarder of the Cries of the World” (Reeves, 2008) in Chapter 25 of the Lotus Sutra (the Sanskrit original deriving from the1st century CE, Chinese translations occurring in the third to sixth Centuries CE).

As the centuries passed and as Buddhism spread from its origin in India to Tibet, China and South East Asia, Avalokitasvara changed into female form (Yü, 2000). In Tibet, the Bodhisattva became Tara (Blofeld, 1979; Shaw, 2006). Tara herself is manifest in many different ways. Among them are white Tara, the goddess of Compassion, and green Tara, the goddess of Enlightenment. The illustration below shows an Indian stone sculpture of Avalokitasvara (9th Century CE) and a gilt copper-alloy casting of Tara (14th Century CE) from Tibet or Nepal and now in the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena. Avalokitasvara is holding a lotus flower. Tara’s left hand shows the mudra (gesture) of teaching and her right hand the mudra of charity.

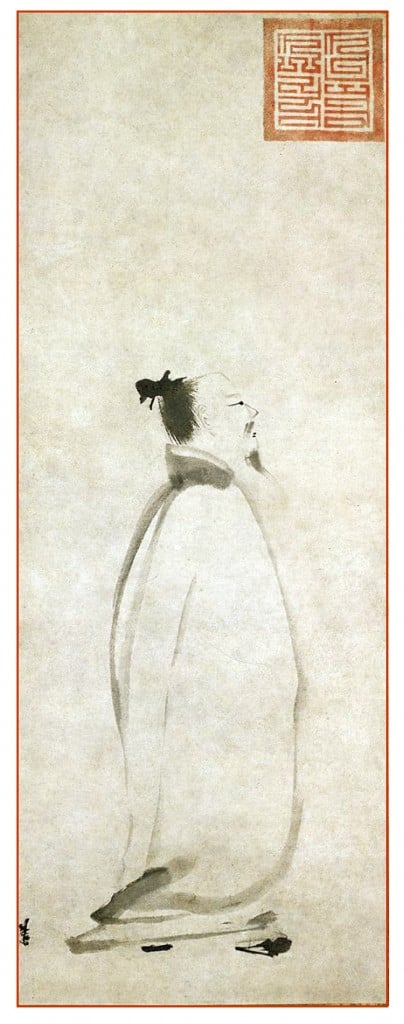

In China Avalokitasvara evolved into Guanshiyin (the Chinese translation of “the one who perceives the sounds of the world”) or Guanyin (pinyin; Kuan Yin in the Wade-Giles romanization). In Japan Guanyin became Kannon, re-assuming a male identity. The illustrations below shows a painted wooden carving of Guanyin (circa 1100 CE) in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas, and a colossal statue of Guanyin (2015) in the Tsz Shan Monastery in Hong Kong.

The Jesuits first arrived in China in the 16th Century. Christian concepts soon became part of life and culture in Southern China. One particular effect was the syncretism (from Greek syn together and krassis mixture) of Guanyin and the Virgin Mary (Paul, 1983; Reis-Habito, 1993). The illustration below from Pham (2021) shows two ivory carvings in the Metropolitan Museum of Ar in New York: a European representation of Mary (13th Century) and a Chinese representation of Guanyin (16th Century).

The Eternal Feminine

With the Scientific Revolution and the Age of the Enlightenment, reason began to exert itself in the affairs of the soul. The existence of God was either denied, or considered only in the abstract. However, cold reason could not handle the emotions, which came to the fore in the Romantic Movement. Feminine forces were the means to handle feelings.

At the end of Goethe’s Faust Part II (1831), Faust, who had sold his soul to the devil in order to achieve knowledge and power, is saved from damnation by the intercession of female heavenly powers. Their final chorus in the play celebrates the power of the “Eternal Feminine.”

Alles Vergängliche All that has happened

Ist nur ein Gleichnis; Is only a parable;

Das Unzulängliche The insufficient

Hier wird’s Ereignis; Is now fulfilled;

Das Unbeschreibliche The indescribable

Hier ist’s getan; Is now realized;

Das Ewig-Weibliche The Eternal Feminine

Zieht uns hinan. Leads us upward.

The chorus has been set to music by Schumann in his Scenes from Goethe’s Faust (1853), Liszt in his Faust Symphony (1880) and by Mahler in his Symphony No 8 (1910). The following is the Mahler version:

Theosophy

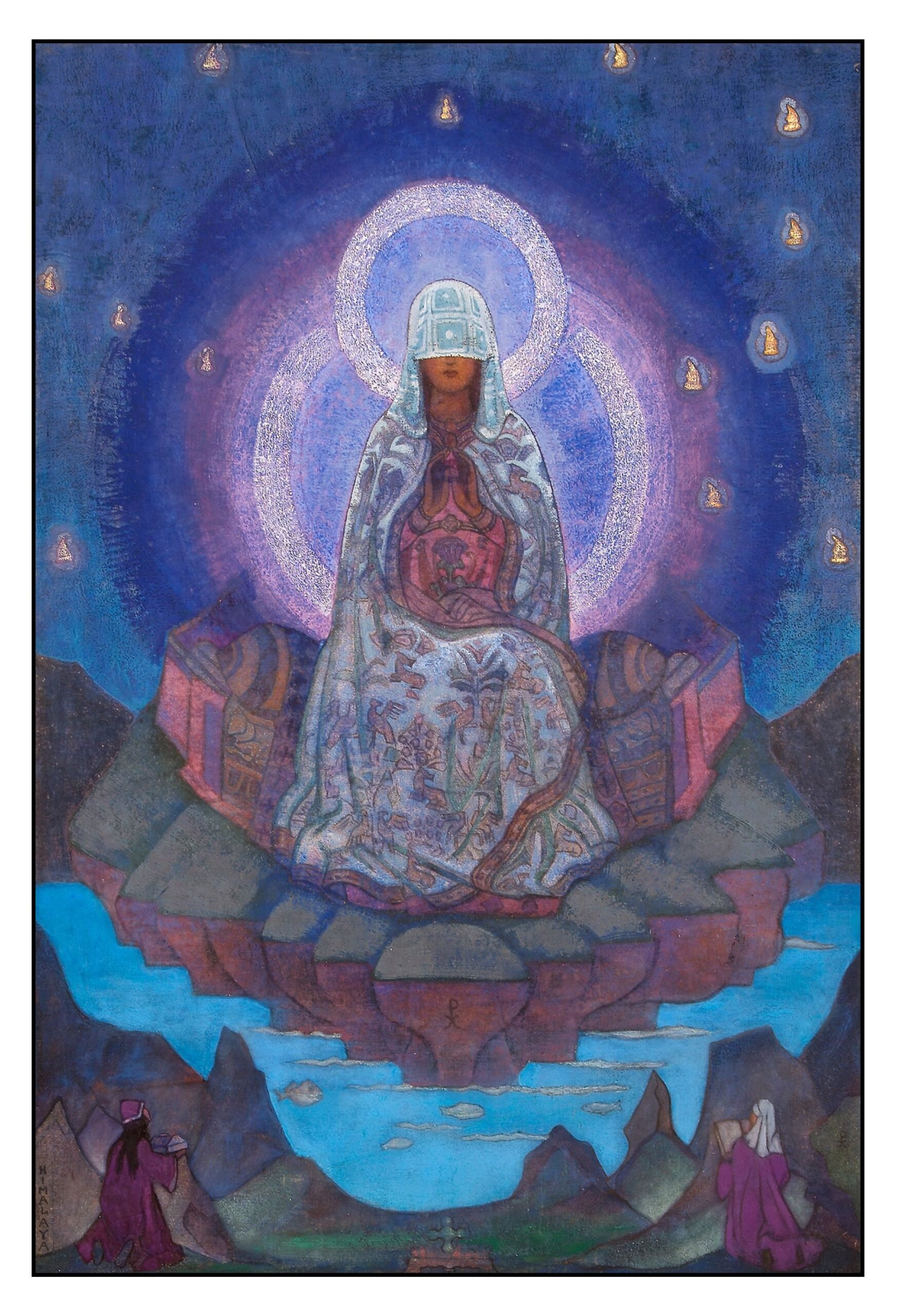

From 1875 to the middle of the 20th Century the Theosophical Movement exerted an uneasy influence on our thinking. Under the initial direction of Helena Blavatsky (1831 -1891), the movement combined Western esotericism and spiritualism with Eastern religious thought, and added a dash of charlatanism. Theosophy did promote of peace in a world enamoured of war and it did increase Western understanding of Eastern spiritual ideas. However, it ultimately foundered on its own fakery. The illustration on the right shows a painting of The Mother of the World (1937) by the Theosophist painter and explorer Nicholas Roerich.

The Gaia Hypothesis

In the 1970s, studies of how the Earth’s atmosphere constantly maintained parameters of temperature and pH that were optimum for the continuation of life led to the Gaia hypothesis, named after the Greek Goddess of the Earth, the primordial mother of all life:

the total ensemble of living organisms which constitute the biosphere can act as a single entity to regulate chemical composition, surface pH and possibly also climate. The notion of the biosphere as an active adaptive control system able to maintain the Earth in homeostasis we are calling the ‘Gaia’ hypothesis (Lovelock and Margulis, 1974)

According to the Gaia hypothesis, human life is just a component of a larger self-regulating organism, the planetary biosphere. Some are skeptical of this hypothesis, claiming it describes the Earth’s process as determined by its future ends – teleological – rather than by its antecedent causes – mechanistic. However, just because science does not easily accommodate purpose does not mean that there is no underlying purpose to the universe.

The Gaia hypothesis has gained much recent support from the modern environmental movement. In some sense humanity has become a cancer on the life of the planet. Unchecked climate change threatens the homeostasis of the world and the life of everyone.

Feminist Theology

During the past few decades, feminist philosophers have challenged the androcentricity of the Christianity and Judaism (Anderson, 1998; Christ, 2003; Goldenberg, 1979; Johnson, 1984, 1992). These thinkers have pointed out the unfairness and inappropriateness of restricting the priesthood to men. And they have criticized mainstream theology for its focus on logic at the expense of intuition. One cannot prove the existence of God, but one can feel it.

Many people handle the unknowns of life by believing in the ethical instructions and the explanatory narratives that are available in religion. Science does not teach us what to do and does not always get us through the night. By providing a purpose to life and by promising ways to approach suffering and death, religion can help. Feminist religion – “theology” (Goldenberg, 1979) with its stress on grace and compassion promises to be far more effective than present mainstream theology.

References

Anderson, P. S. (1998). A feminist philosophy of religion: the rationality and myths of religious belief. Blackwell.

Apuleius (2nd Century CE, selected by Singer, P., translated by Finkelpearl, E. D., and illustrated by Kendel, A., & Kendel, V., 2021). The golden ass. Liveright (division of W. W. Norton).

Barstow, A. L. (1983). The prehistoric goddess. In C. Olson (Ed). The Book of the goddess, past and present: an introduction to her religion. (pp 7-15). Crossroad.

Blofeld, J. (1979). Kuan Yin and Tara: Embodiments of wisdom-compassion. Tibet Journal, 4(3), 28-36

Christ, C. P. (2003). She who changes: re-imagining the divine in the world. Palgrave-Macmillan.

Devine, L. (2014). How Shekhinah became the God(dess) of Jewish Feminism. Feminist Theology, 23(1) 71–91.

Faure, B. (2008). The power of denial: Buddhism, purity, and gender. Princeton University Press.

Graves, R. (1948, amended and enlarged, 1961). The White Goddess; a historical grammar of poetic myth. Faber and Faber.

Green, A. (2002). Shekhinah, the Virgin Mary, and the Song of Songs: Reflections on a Kabbalistic symbol in its historical context. AJS Review, 26(1), 1-52.

Goldenberg, N. R. (1979). Changing of the gods: feminism and the end of traditional religions. Beacon Press

Johnson, E. A. (1984). The incomprehensibility of God and the image of God male and female. Theological Studies, 45(3), 441–465.

Johnson, E. A. (1985). The Marian tradition and the reality of women. Horizons, 12(1), 116–135.

Johnson, E. A. (1992). She who is: the mystery of God in feminist theological discourse. Crossroad.

Kinsley, D. R. (1986). Hindu goddesses: visions of the divine feminine in the Hindu religious tradition. University of California Press. Available at Arkiv.org

Laura, J. (2015). Kabbalah: in its beginnings. Women in Judaism, 12(2), 1–16.

Leith, M. J. W. (2021). The Virgin Mary: a very short introduction. Oxford University Press.

Lovelock, J. E., & Margulis, L. (1974). Atmospheric homeostasis by and for the biosphere: the Gaia hypothesis. Tellus, 26, 2-10.

Matter, E. A. (1983). The Virgin Mary: a Goddess? In C. Olson (Ed). The Book of the goddess, past and present: an introduction to her religion. (pp 80-96). Crossroad.

Neumann, E. (1963, second edition 1972, translated by R. Manheim,). The great mother: an analysis of the archetype. Princeton University Press.

Pattanaik, D. (2000). The Goddess in India: the five faces of the eternal feminine. Inner Traditions International.

Paul, D. (1983) Kuan-Yin: Savior and savioress in Chinese Pure Land Buddhism. In C. Olson (Ed). The Book of the goddess, past and present: an introduction to her religion. (pp 161-175). Crossroad.

Perkins, P. (1985). Sophia and the Mother-Father: the Gnostic Goddess. In C. Olson (Ed). The Book of the goddess, past and present: an introduction to her religion. (pp 97-109). Crossroad.

Pew Research Center (2016). The gender gap in religion around the world. (March 22, 2016).

Pham, K.D. (2021). Compassion, Mercy, and Love: Guanyin and the Virgin Mary. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Reeves, G. (2008). The Lotus Sutra: a contemporary translation of a Buddhist classic. Wisdom Publications.

Reis-Habito, M. (1993). The Bodhisattva Guanyin and the Virgin Mary. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 13, 61-69

Rubin, M. (2009). Mother of God: a history of the Virgin Mary. Yale University Press.

Scholem, G. (1965, reprinted 1996). On the Kabbalah and its symbolism. Schocken Books.

Scholem, G. (1991). The feminine element in divinity. In G. Scholem. On the mystical shape of the Godhead: basic concepts in the Kabbalah. (pp 140-196). Schoken Books.

Shaw, M. E. (2006). Buddhist goddesses of India. Princeton University Press.

Smith, C. (1985). The symbol of the Shekhinah: the feminine side of God. European Judaism, 19(1), 43–46.

Stone, M. (1978). When God was a woman. Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich.

Yü, C.-F. (2000). Kuan-yin the Chinese transformation of Avalokiteśvara. Columbia University Press.