Stonehenge

Over five thousand years ago the Neolithic people of Britain began to erect a monumental stone structure known as “Stonehenge” on the Salisbury Plain. The name likely means “hanging” or “suspended” stones. The structure underwent several changes over the years of its construction, reaching its final form around 2000 BCE.

The stones are of two kinds. The largest are the sarsens, which have their origin in the hills about 40 km north of Stonehenge. The word “sarsen,” first used at the time of the Crusades, comes from “Saracen” and essentially means “pagan.”

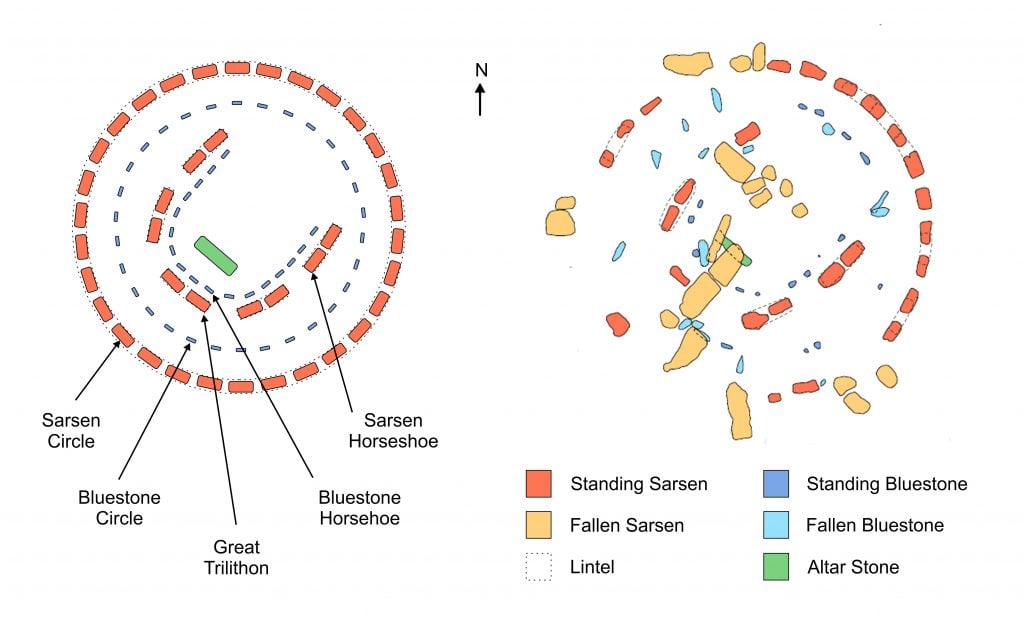

The smaller bluestones come from the Preseli Mountains in Southwest Wales 240 km away. Most archaeologists currently believe that these were transported across the Bristol Channel and then overland to Stonehenge. The bluestones may have been used in several ways during the different periods of construction. In the final form of the monument they are arranged within the outer circle of sarsens and within the inner horseshoe of larger sarsens.

The monument has long been a symbol of ancient Britain. Over the years, however, our understanding of it has changed radically. This posting considers how Stonehenge has interacted with the British imagination. Because of its striking appearance, images are given as much space as words.

Past and Present Structure

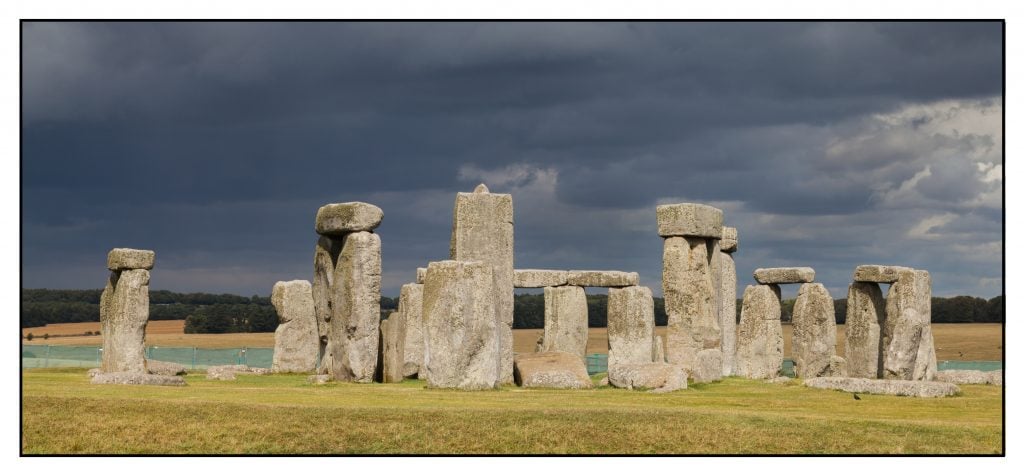

The following figure shows a photograph of the monument taken from the Southwest by Diego Delso in 2014. A larger version of the photograph is available from Wikipedia.

In the center of the figure is a large standing stone – the only stone still upright from the great trilithon (“three stones” – two erect stones with a superimposed lintel). At its top is a small peak representing the tenon of a mortice-and-tenon joint that served to maintain the lintel on top of the two uprights.

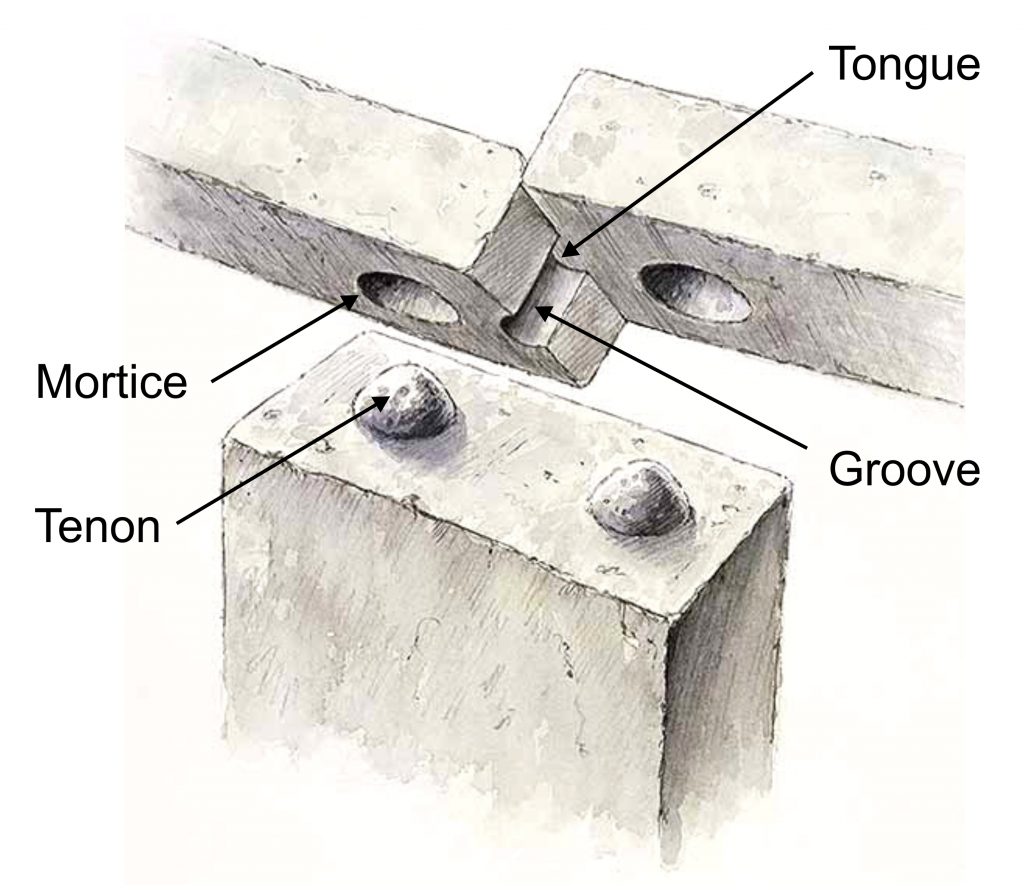

Behind and to the right of this central stone can be seen the surviving arches of the outer sarsen circle. The lintels on this circle are held in position using tongue-in-groove as well as mortice-and-tenon joints. These techniques are similar to those used in woodworking (Chippindale, 2012, p 12; Johnson, 2008, pp 142-148). The figure on the right (modified from the English Heritage site) illustrates these procedures.

Behind and to the right of this central stone can be seen the surviving arches of the outer sarsen circle. The lintels on this circle are held in position using tongue-in-groove as well as mortice-and-tenon joints. These techniques are similar to those used in woodworking (Chippindale, 2012, p 12; Johnson, 2008, pp 142-148). The figure on the right (modified from the English Heritage site) illustrates these procedures.

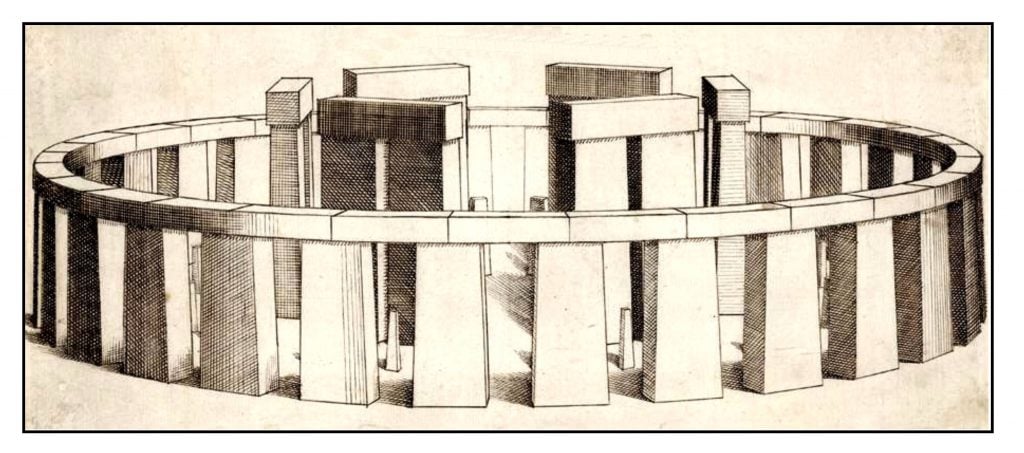

Many of the original stones have collapsed. Some fallen stones were probably long ago broken up and used for other buildings. Others lie on the ground; others are buried. Most of the sarsens on the south and west of the outer circle fell and vanished long ago. The following figure shows on the left a diagram of how the monument might have been in 2000 BCE (based on Johnson, 2008, p. 166). and on the right a plan of the present site (modified from the English Heritage Webpage).

The outer ring of sarsens with the superimposed lintels rose almost 5 m above the ground. The trilithons of the inner sarsen horseshoe varied in height: those at the open end of the horseshoe were about 6 m high, the adjacent trilithons a little higher and the great trilithon at the center of the horseshoe almost 7.5 m. The bluestones are much smaller and quite variable in size and shape. The illustration below shows a digital model by Hypnagogia of how the completed monument might have appeared as viewed from the Northeast at sunrise.

The great trilithon collapsed long ago. The eastern upright broke in two over the altar stone. The western upright fell only halfway and was for many years held up at an angle by the inner bluestone. It was re-erected and stabilized in 1901. The first set of stones whose fall is historically recorded is the southwestern trilithon which collapsed in 1797. It was re-erected in 1958.

The great trilithon collapsed long ago. The eastern upright broke in two over the altar stone. The western upright fell only halfway and was for many years held up at an angle by the inner bluestone. It was re-erected and stabilized in 1901. The first set of stones whose fall is historically recorded is the southwestern trilithon which collapsed in 1797. It was re-erected in 1958.

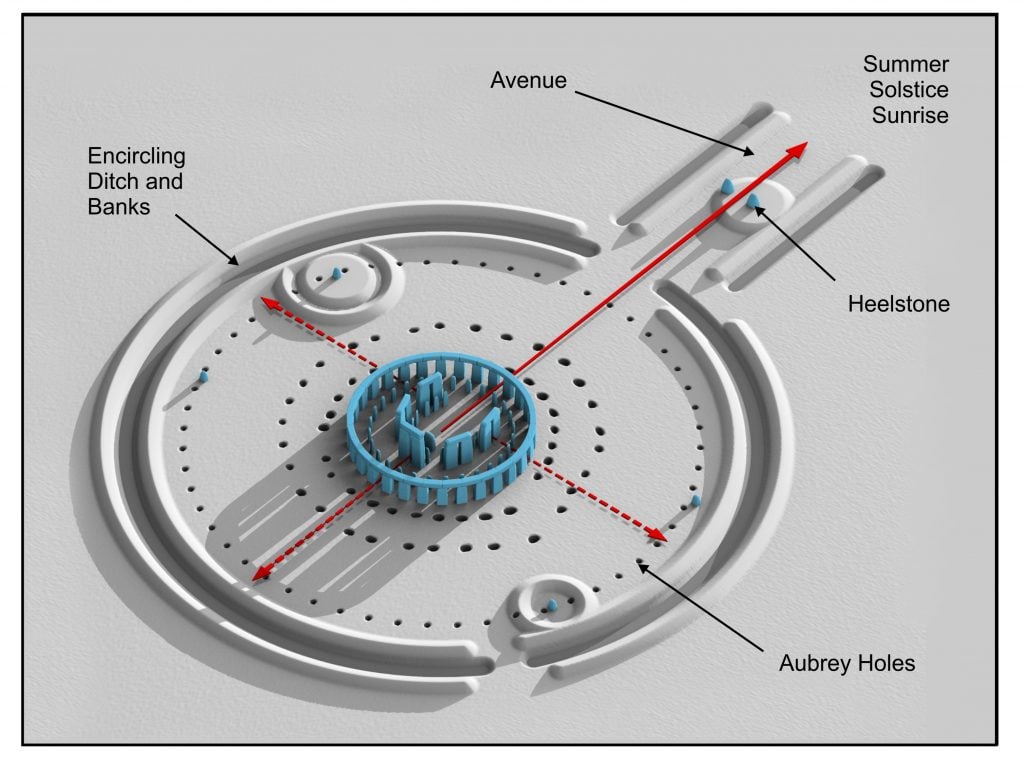

As shown on the right, the standing stones are at the center of a larger circle marked by a ditch and by the Aubrey Holes. These are the oldest part of the monument, predating the sarsens by several hundred years. Parker Pearson (2012, pp 181-186) has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have been the original location of the bluestones, which were later removed and placed within the sarsen monument.

Early Views of Stonehenge

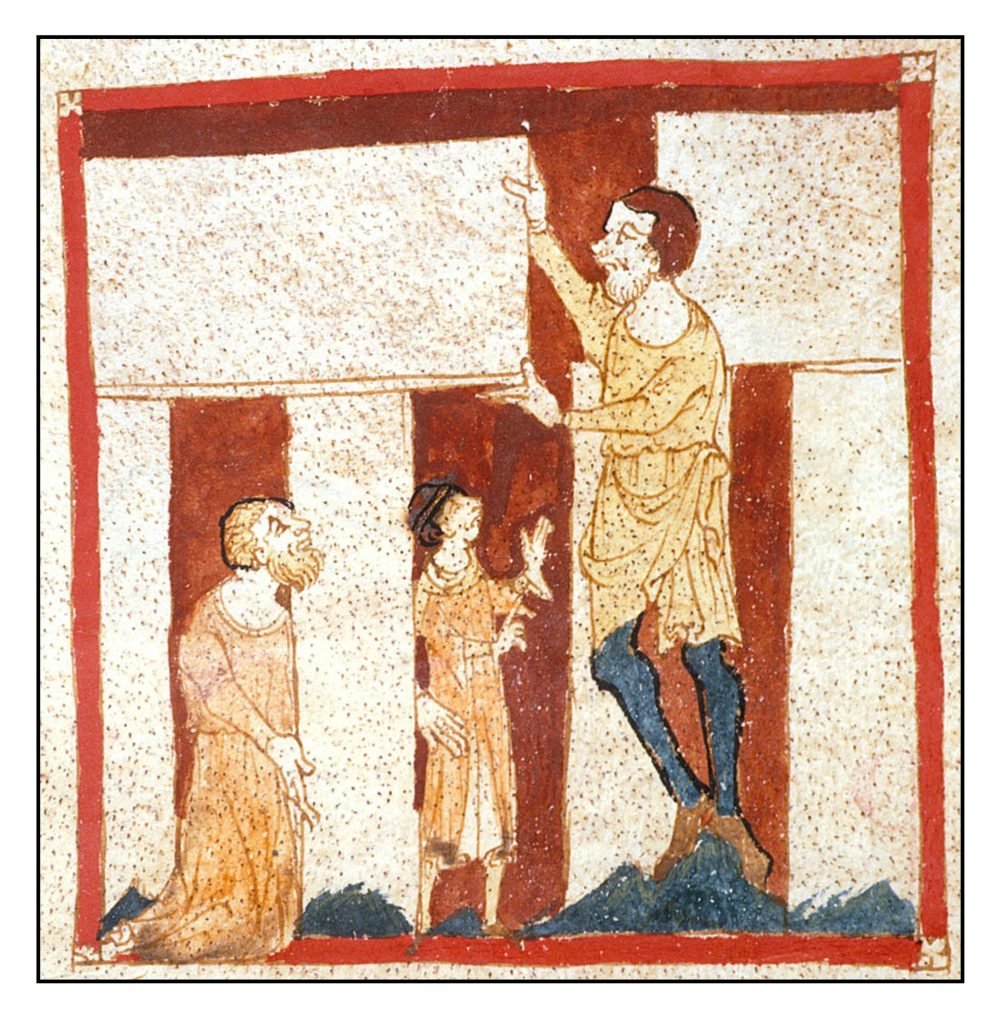

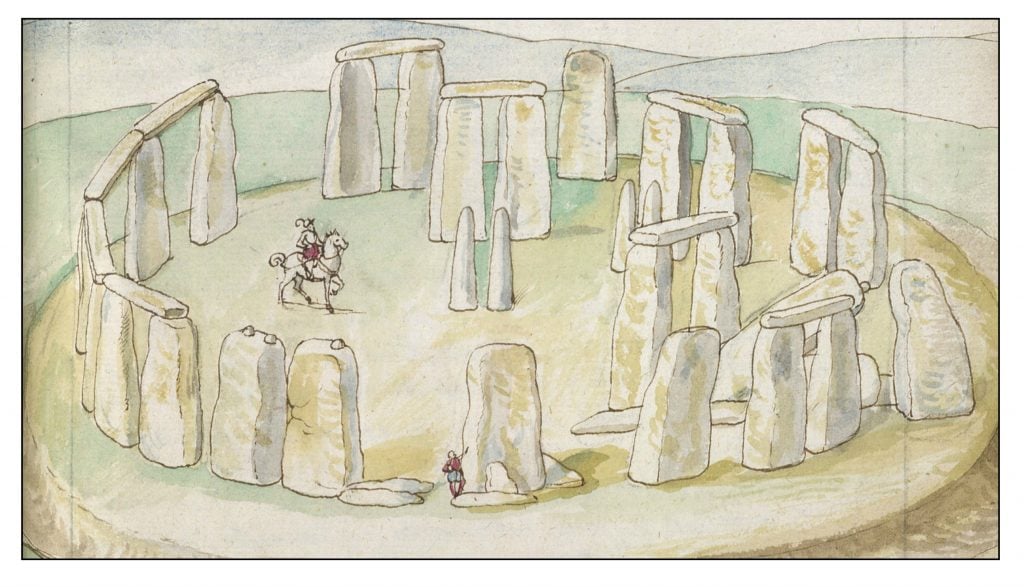

One of the earliest accounts of Stonehenge occurs in Geoffrey of Monmouths’s History of the Kings of Britain (1136). Chapters 10 to 12 of Book 8 provide a fanciful tale of the stones being erected by giants under the supervision of Merlin, the sage of the Arthurian legends. The Egerton 3028 manuscript in the British Library contains an illustration of this story.

The first “realistic” depiction of Stonehenge was a 1575 watercolour by Lucas De Heere, a Flemish refugee in England. The painting shows the general size and arrangement of the stones as viewed from the Northwest but is woefully incorrect in its detail (Chippindale, 2012, pp 33-35). The most glaring error is that the monolith of the great trilithon is depicted as leaning outwards rather than inwards.

The great English architect Inigo Jones studied the monument in the 17th Century. John Webb collected Jones’ notes and published them posthumously in 1655 in a book entitled The Most Notable Antiquity of Great Britain, Vulgarly called Stone-Heng on Salisbury Plain. Jones thought that the stones were erected as a temple by the Romans during their occupation of Britain. He considered the ancient Britons too savage to have built a monument of such perfectly classical proportions.

This idea was disputed by John Aubrey, the author of the famous Brief Lives, who published his Monumenta Britannica in 1665. He made a careful study of the Stonehenge site and noted the circle of chalk pits around the stone monument, which are still called Aubrey Holes (Johnson, 2008, p. 57). He pointed out that the Britain and Ireland contained multiple Neolithic monuments and stone circles, and that many of these were in areas where the Romans had never penetrated. He therefore suggested that they were erected by the Britons as “Temples of the Druids” (Hill, 2008, p 33).

This idea was disputed by John Aubrey, the author of the famous Brief Lives, who published his Monumenta Britannica in 1665. He made a careful study of the Stonehenge site and noted the circle of chalk pits around the stone monument, which are still called Aubrey Holes (Johnson, 2008, p. 57). He pointed out that the Britain and Ireland contained multiple Neolithic monuments and stone circles, and that many of these were in areas where the Romans had never penetrated. He therefore suggested that they were erected by the Britons as “Temples of the Druids” (Hill, 2008, p 33).

Aubrey’s proposal was promoted by William Stukeley, a friend of Isaac Newton. He published Stonehenge, A Temple Restor’d to the British Druids in 1740. Initially he had made some accurate observations of Stonehenge: he was the first to notice the “avenue” leading to Stonehenge from the Northeast (Chapter 8), and he noted that the monument and the avenue were oriented along a line pointing to the sunrise at the summer solstice (Chippindale, 2012, p. 75).

Imaginative Interpretations of Stonehenge

However, Stukeley soon let his imagination take over, and he concocted a narrative of how the Jewish patriarchs had visited England in ancient times with the Phoenicians (Chippindale, 2012, Chapter 8; Lewis Williams & Pearce, 2005, pp 169-172; Hill, 2008, pp. 39-49). This was all part of a grand universal history of humanity, with the pure original religion being initially subverted by idolatry and then restored by Jesus. He considered Stonehenge as a temple of this primordial religion, where divine observances were conducted by the Celtic Druids. Stukeley was so enthusiastic about these ideas that he took to calling himself Chyndonax, Prince of the Druids. His work has exerted a tremendous influence on the popular views of Stonehenge. Modern dating methods have shown that Stonehenge was built by Neolithic Britons more than a thousand years before the Iron-Age Celts (who only became evident in Britain by after 1000 BCE). Nevertheless, to this day druids still conduct services at Stonehenge on the days of the summer solstice.

Some of Stukeley’s ideas are present in William Blake’s poem Jerusalem:

And did those feet in ancient time,

Walk upon England’s mountains green:

And was the holy Lamb of God,

On England’s pleasant pastures seen!

And did the Countenance Divine,

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among these dark Satanic Mills?

Bring me my Bow of burning gold;

Bring me my Arrows of desire:

Bring me my Spear: O clouds unfold!

Bring me my Chariot of fire!

I will not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand:

Till we have built Jerusalem,

In England’s green & pleasant Land

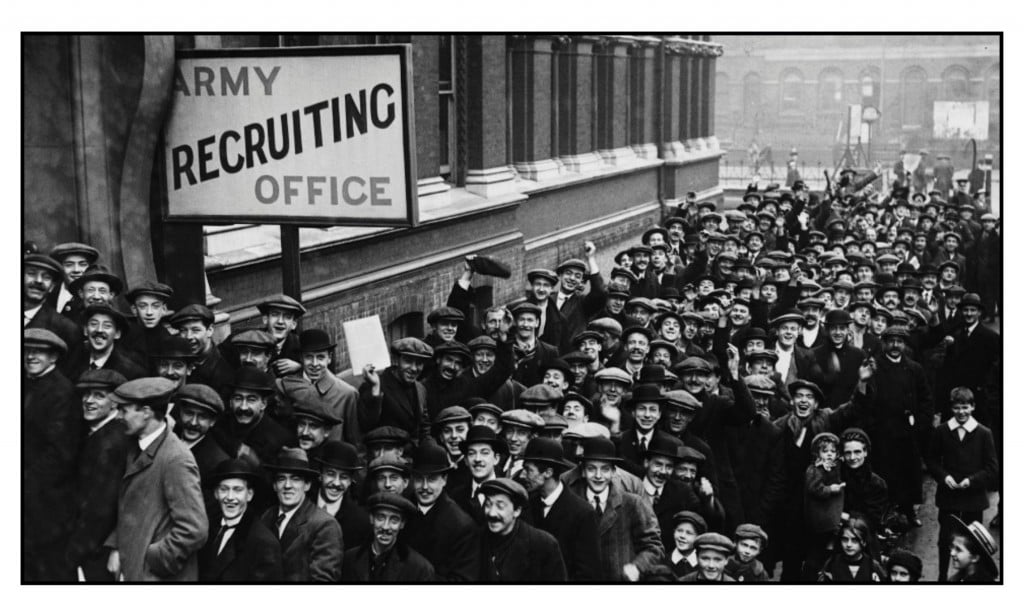

Hubert Parry’s 1916 musical setting of this poem has become an extremely popular anthem, traditionally sung with great fervor and flag-waving on the last night of the Proms.

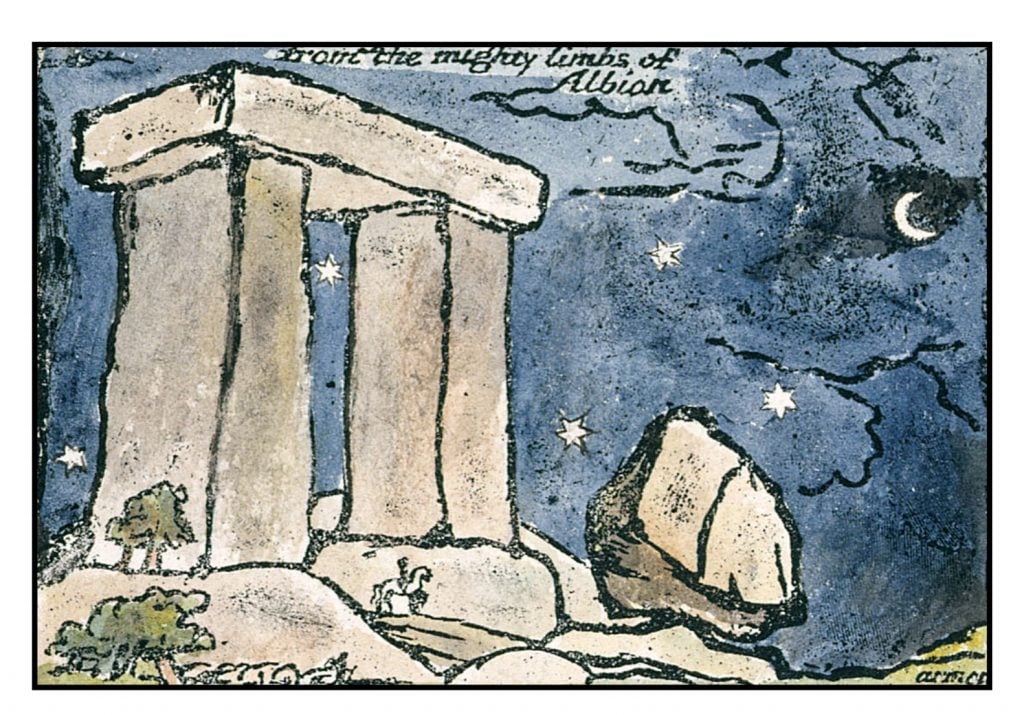

Blake’s poem is contained in the preface to his illuminated book Milton a Poem (1811). The poem deals with the need for the creative imagination to liberate mankind from slavery to established morality. Some illustrations of megaliths (e. g. part of page 4 shown on the right) are included in this long poem, and at times Blake seems to suggest these as evidence of religion’s Satanic power over the people. Some interpreters have even considered the “Satanic Mills” of the second verse of the prefatory poem mean the established churches rather than the cotton mills of the industrial revolution.

Blake’s poem is contained in the preface to his illuminated book Milton a Poem (1811). The poem deals with the need for the creative imagination to liberate mankind from slavery to established morality. Some illustrations of megaliths (e. g. part of page 4 shown on the right) are included in this long poem, and at times Blake seems to suggest these as evidence of religion’s Satanic power over the people. Some interpreters have even considered the “Satanic Mills” of the second verse of the prefatory poem mean the established churches rather than the cotton mills of the industrial revolution.

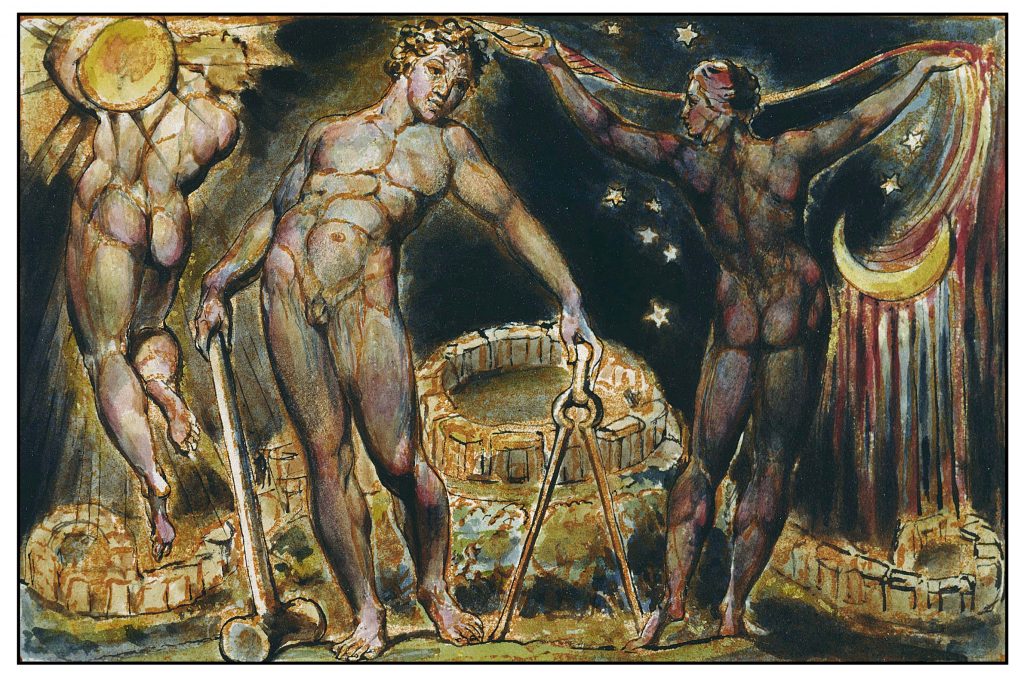

However, Blake’s view of Stonehenge was ambiguous. The last page of a later illuminated book Jerusalem: The emanation of the giant Albion. (1821) contains a striking image:

The central male figure is Los, the personification of imaginative energy, with the hammer and tongs he uses to create. On the left is his spectre carrying the sun. On the right is his emanation, Enitharmon, the female personification of spiritual beauty. She holds what appears to be a spindle, from which descend the threads of life. Below them is a serpentine line of trilithons with a central circle similar to the Stonehenge. The meaning of this final image is not clear. In his notes to the facsimile edition of the book, Paley suggests that these structures may represent the creation of Jerusalem in England. However, the words of a prophet can be difficult to understand.

Romanticism

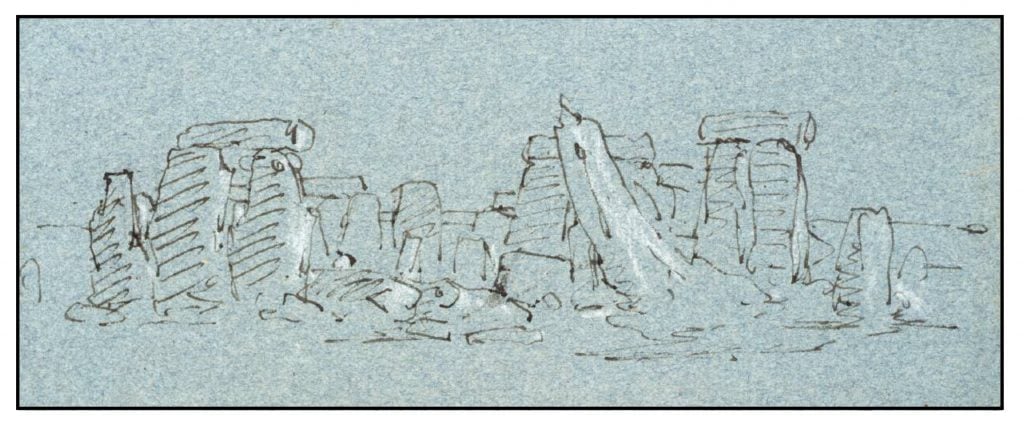

J. M. W. Turner visited Stonehenge in 1799. He made several drawings of the ruins. The following small sketch represents a view from the West.

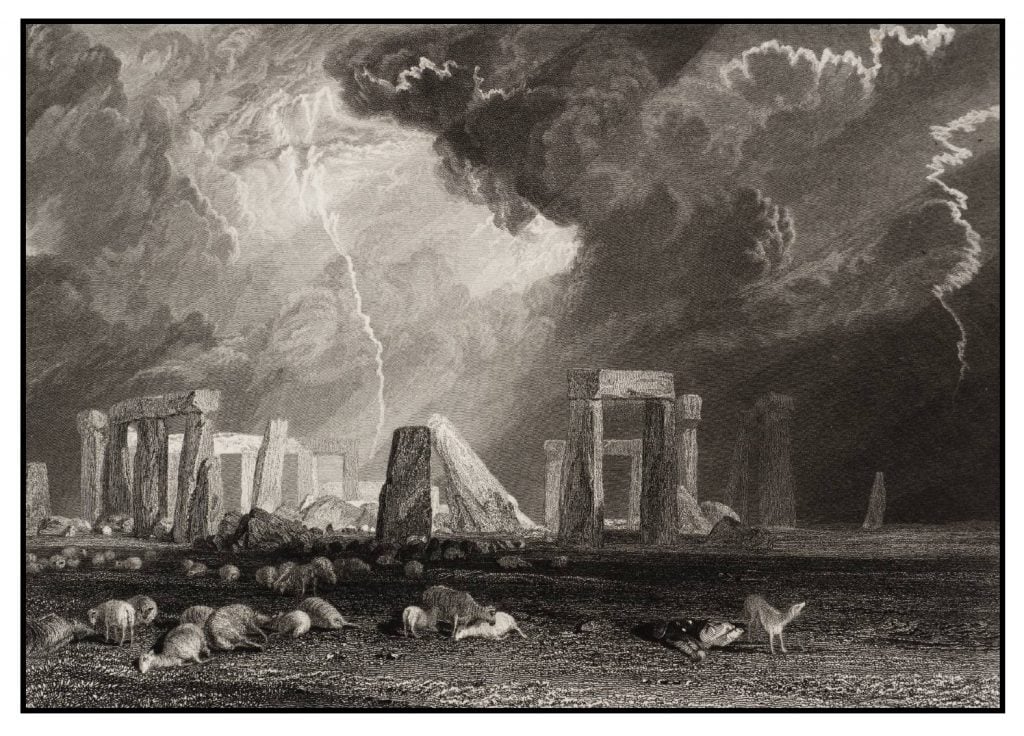

In 1827 he created a watercolor based on his earlier sketches. The final painting depicts Stonehenge during a storm. Lightning strikes the ground in the middle of the ruin, killing many sheep and the shepherd who lies in the right foreground. The shepherd’s dog howls disconsolately. An 1829 engraving of this image became very popular, appealing to the public’s new romantic fascination with the unrestrained power of nature:

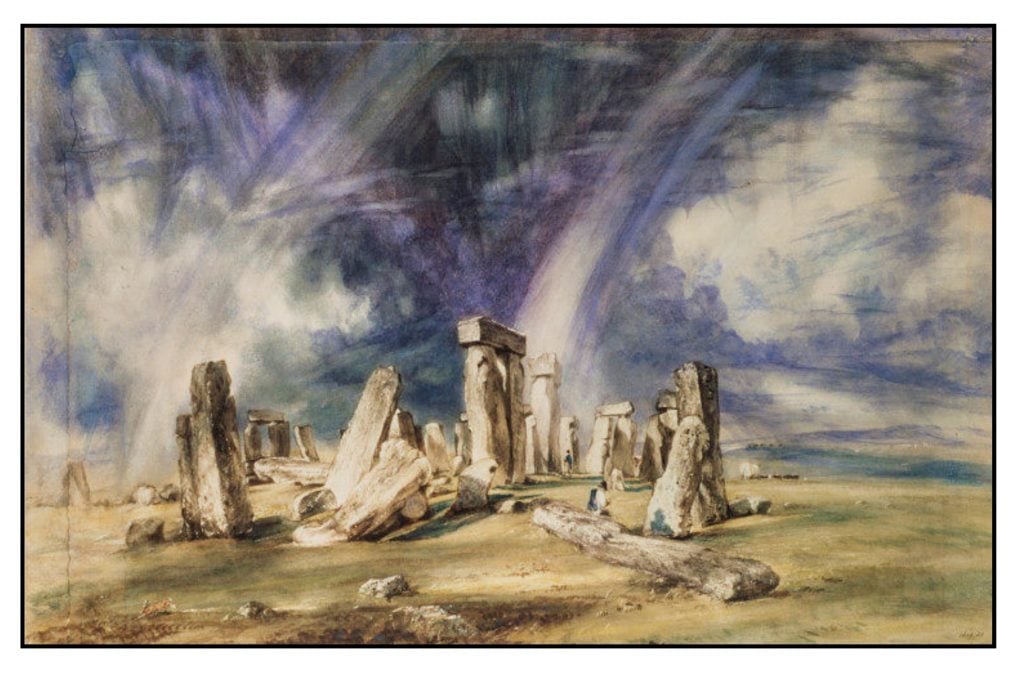

John Constable’s 1835 watercolor of Stonehenge also sets the monument in a scene of great natural power. The view is from the South. In the North are dark storm clouds, onto which the sun has cast a double rainbow. At the time of this painting, Constable was grieving for his recently deceased wife. The painting is imbued with sadness; the rainbows are drained of color.

Constable (quoted in Chippindale, 2012, p 105) provided a caption when his painting was first exhibited:

The mysterious monument of Stonehenge, standing remote on a bare and boundless heath, as much unconnected with the events of past ages as it is with the uses of the present, carries you back beyond all historical recall into the obscurity of a totally unknown period.

Modernism and Stonehenge

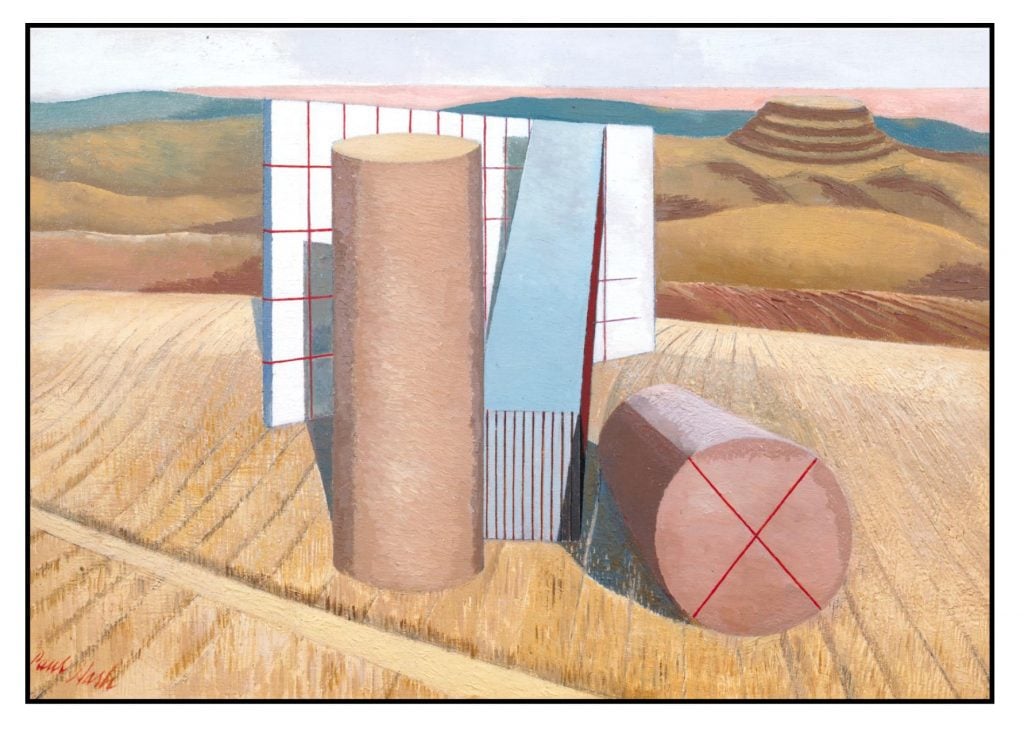

The Romantic approach to Stonehenge does not do justice to its austere beauty. However, Modernism also fails to capture the essence of the site. The following is a 1935 painting by Paul Nash entitled Equivalents for the Megaliths. Large geometric shapes are set down in a stylized English landscape. The painting does not convey the power of Stonehenge or the other megalithic monuments, though it does suggest their incomprehensibility.

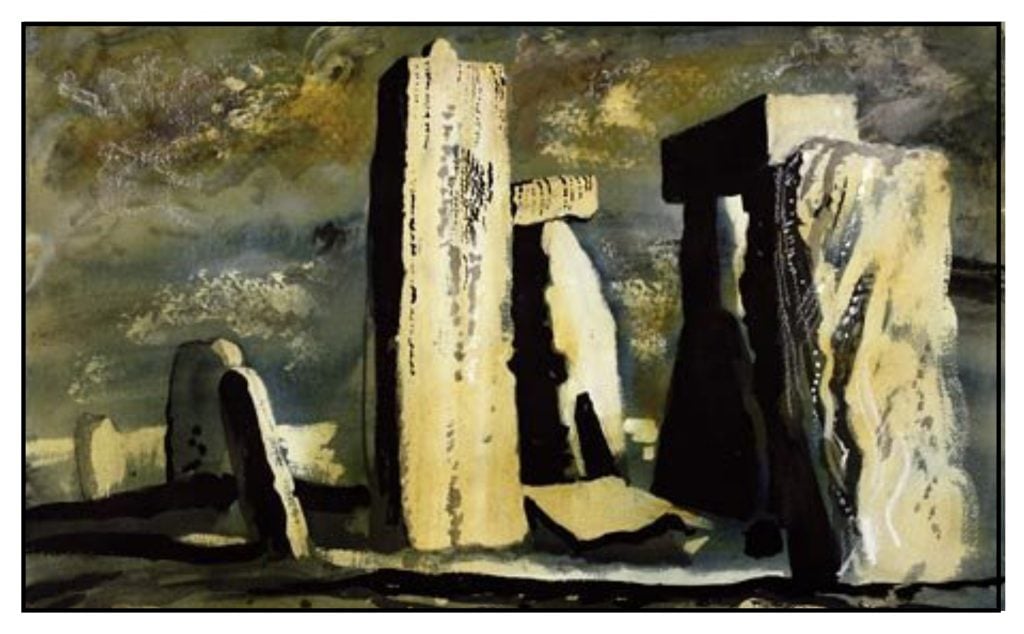

John Piper’s ink-and-wash painting from 1981 is more successful. This considers Stonehenge form the point of view of a Romantic Modernist.

Photographs of Stonehenge

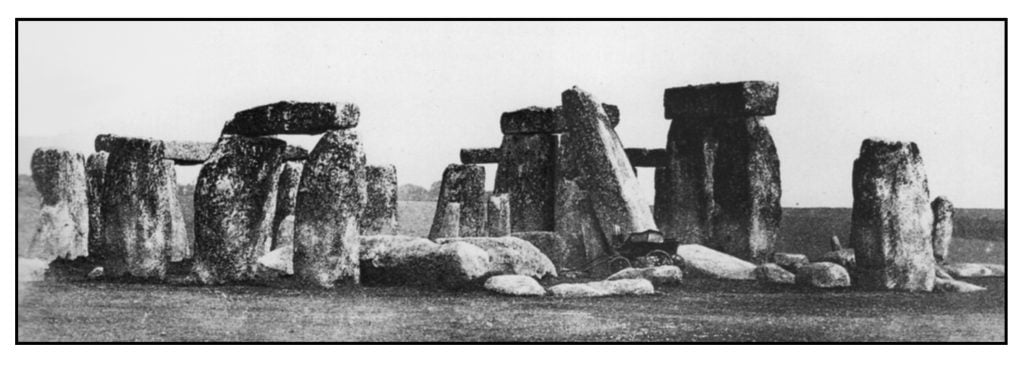

Photographs provide a realistic view of Stonehenge. The following is the first known photograph, a calotype by William Russell Sedgfield in 1853 (copied from Chippindale, p.149). The view is from the west. A carriage stands by the leaning upright of the great trilithon.

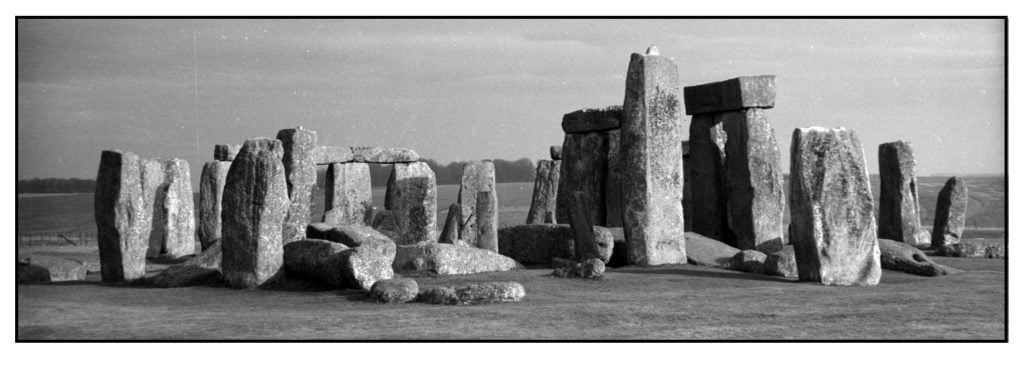

Photographs also provide a record of the reconstruction. The following photograph by John Piper shows the upright resurrected. This photograph was taken before the 1958 reconstruction of the southwestern trilithon (which can be seen in the 2014 photograph at the beginning of this posting).

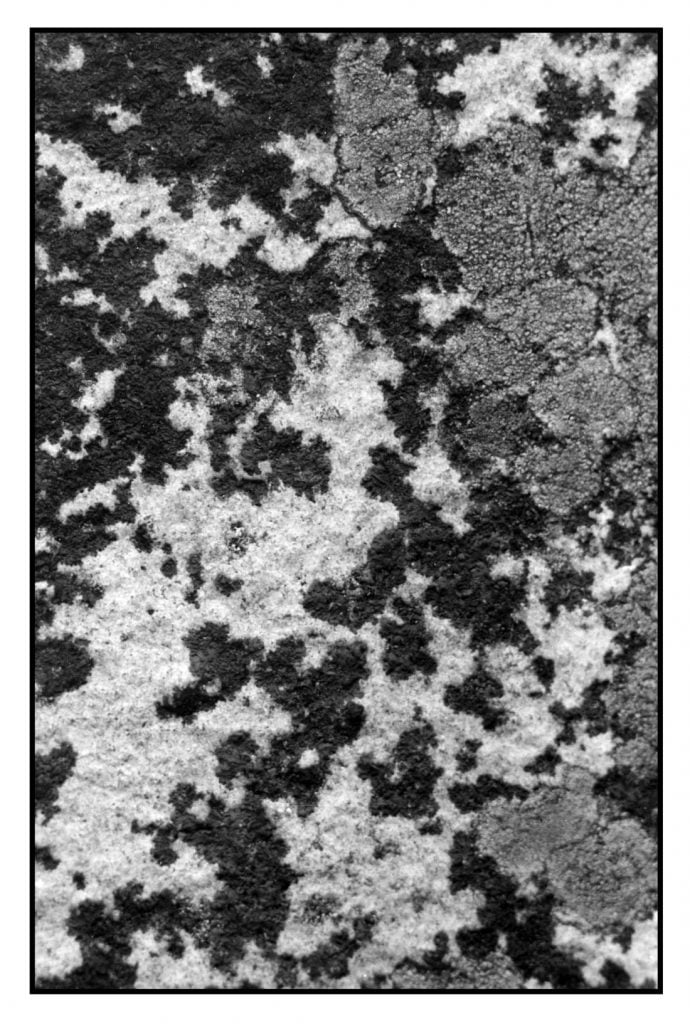

John Piper in another undated photograph in the Tate Britain collection focuses on the surface of one of the stones. In so doing he captures their very tactile impression. Unlike other megaliths, the stones at Stonehenge were dressed using stone axes so that their inner surfaces were smooth. Over the years lichen have painted upon them in an abstract expressionist style.

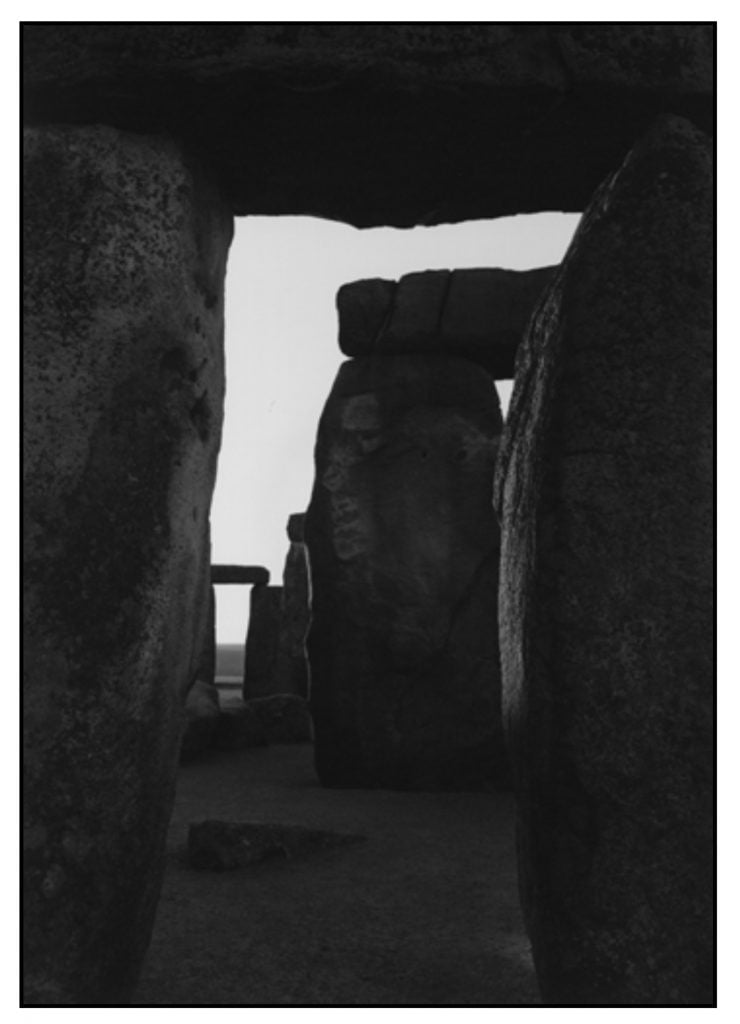

Photographs can give a sense of the place as well as providing a simple record. The photograph to the left by Paul Caponigro is entitled Inner Trilithon through Circle Stones, Stonehenge (1970). Caponigro published a large book of photographs of the Neolithic monuments in Britain, Ireland and France in 1986. The outer reaches of Europe contain numerous stone structures dating back to several thousand years BCE (Mohen, 1999)

Prints of the Stones

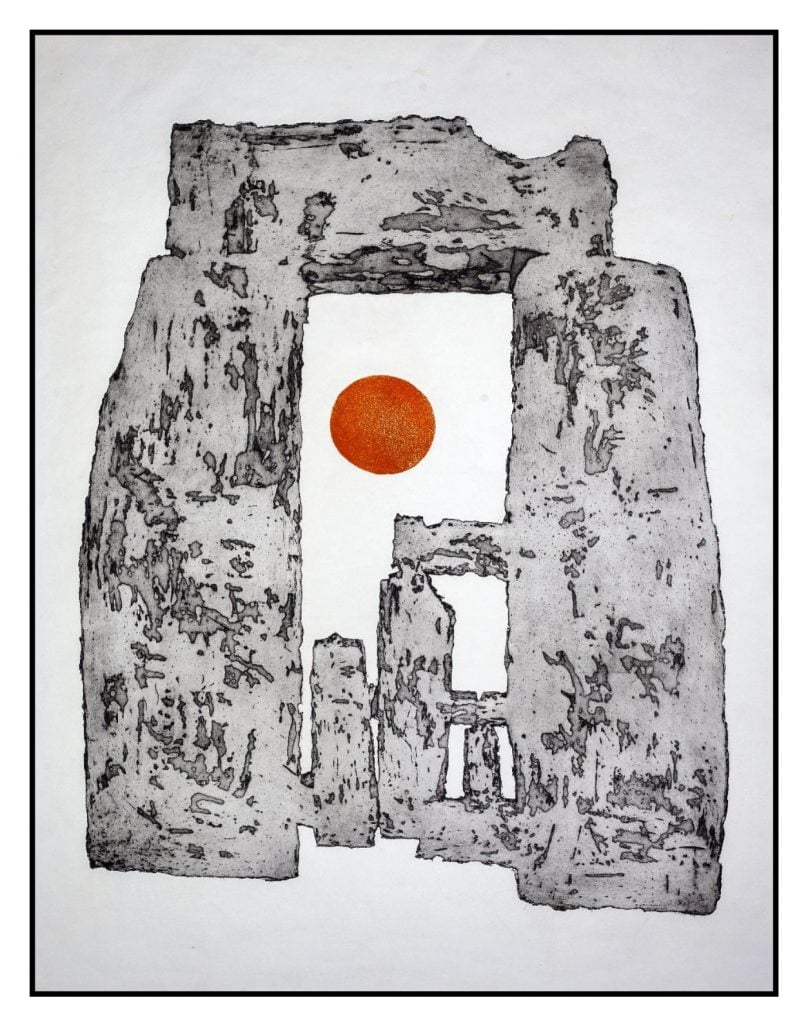

Print-makers have been very successful in capturing the form and feeling of Stonehenge. Perhaps they are more comfortable with stones, since they work closely with them in lithography. Their prints concentrate on how the light plays on the monument. They tend to consider the monument in part rather than in whole. On the right is a 1961 aquatint print by Julian Trevelyan.

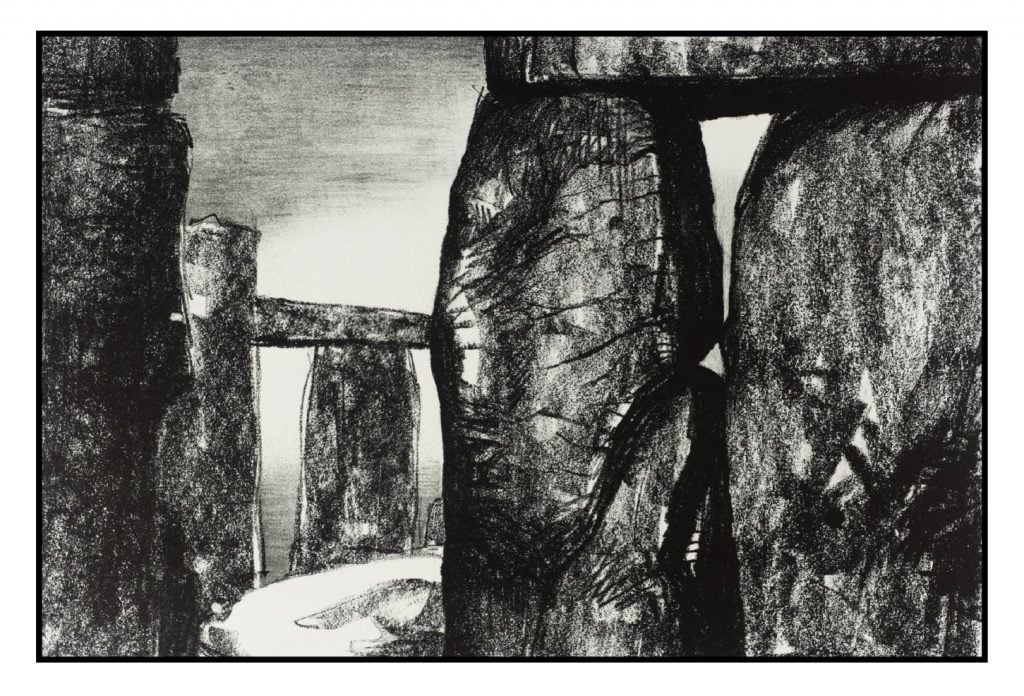

Henry Moore made a series of lithographs of Stonehenge in 1973. All are available at the Tate Britain website. Below is Stonehenge IV:

On the right is a 1974 intaglio by Norman Stevens. Stonehenge at night has a brooding majesty.

Nature of Stonehenge

What purpose did Stonehenge serve? Many fanciful explanations have been proposed with little support other than the imagination (Hutton, 2013). Any ideas that the site served as a place for living are completely dispelled by the lack of any archeological evidence for everyday life. The people who built Stonehenge lived nearby but not at the site of the monument. They stayed close to the River Avon in a place called Durrington Walls, where archeologists have found signs of ancient wooden buildings, and the refuse of everyday life (Parker Pearson, 2012). Some of the wooden buildings, such as Woodhenge, were circular. The people then used the techniques of the wooden buildings when constructing Stonehenge.

Why then did they build their great megalithic monument? Was it a place for meetings or a site for religious observances? One would have thought that the objects used in such meetings or rites might have remained, but the site is largely empty of anything unrelated to the stones or to the burials. Was Stonehenge a shrine where the sick went for healing under the benign influence of the stones? The human remains do not show evidence of obvious illness. Was Stonehenge a celestial observatory to help predict the seasons and eclipses (Hawkins & White, 1965)? When one stands at the base of the great trilithon at the summer solstice, one can see the sun rise over the Heel Stone. Although the monument is laid out along the line of the solstices, most archeologists now feel that this was more of gesture to the heavens rather than a way to measure them (Brown, 1976; Ruggles & Hoskin, 1999; Hutton, 2013)

Because of the cremated human remains found in the Aubrey Holes, Parker Pearson (2012) has suggested that the site was built as a monument to the dead, perhaps as a place to honor noble ancestors. He tells an intriguing story of how he was told by Ramilisonina, an archeologist from Madagascar, that people in his country spent their lives in wood structures, but gave their dead stone houses to last them for eternity. Other great stone monuments such as the Egyptian pyramids were certainly built as places for the dead, as were the British barrows and dolmens that predated Stonehenge.

Words

Thomas Hardy set the penultimate scene of his 1891 novel Tess of the d’Urbevilles at Stonehenge. Tess has killed Alec, her seducer and tormentor. Tess and Angel Clare are now fleeing at night across the Salisbury Plain. When they reach Stonehenge, Tess is too tired to go on, and she lies down on one of the recumbent stones. She asks Angel if he believes that they might meet again after they are dead.

Like a greater than himself, to the critical question at the critical time he did not answer; and they were again silent. In a minute or two her breathing became more regular, her clasp of his hand relaxed, and she fell asleep. The band of silver paleness along the east horizon made even the distant parts of the Great Plain appear dark and near; and the whole enormous landscape bore that impress of reserve, taciturnity, and hesitation which is usual just before day. The eastward pillars and their architraves stood up blackly against the light, and the great flame-shaped Sun-stone beyond them; and the Stone of Sacrifice midway. Presently the night wind died out, and the quivering little pools in the cup-like hollows of the stones lay still.

The great stones are silent about what happens after death. They persist through the centuries. They evoke memories of those who built them so that they might, themselves, remember and honor their ancestors. Yet the world has moved on and all those ancient people are no more.

References

Blake, W. (1810, facsimile with annotations by Paley, M. D. 1991). Jerusalem: The emanation of the giant Albion. Princeton, N.J: William Blake Trust/Princeton University Press.

Brown, P. L. (1976). Megaliths, myths, and men: An introduction to astro-archaeology. Poole, Dorset, UK: Blandford Press.

Caponigro, P. (1986). Megaliths. Boston: Little, Brown.

Chippindale, C. (2012). Stonehenge complete. 4th Ed. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Hawkins, G. S., & White, G. B. (1965). Stonehenge decoded. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday.

Hill, R. (2008). Stonehenge. London: Profile Books.

Hutton, R. (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Johnson, A. (2008). Solving Stonehenge: The new key to an ancient enigma. New York: Thames & Hudson.

Lewis-Williams, J. D., & Pearce, D. G. (2005). Inside the Neolithic mind: Consciousness, cosmos, and the realm of the gods. London: Thames & Hudson.

Mohen, J.-P. (1999). Megaliths: Stones of memory. New York: Abrams.

Parker Pearson, M. & Stonehenge Riverside Project (2012). Stonehenge: Exploring the greatest Stone Age mystery. London: Simon & Schuster

Ruggles, C. & Hoskin, M. (1999) Astronomy before history. In M. Hoskin (Ed.) The Cambridge Concise History of Astronomy. (pp. 1–17). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.