Aspects of Etruria

The Etruscans thrived from about 900 to 100 BCE. Although archaeology has revealed much about their life, even more remains unknown. After the Etruscans were assimilated by the Romans, their written history was lost. Although the Emperor Claudius wrote a 20-volume history of the Etruscans, not a page of this has survived.

Popular ideas that the Etruscans originated in Greece, Turkey or Phoenicia have given way to the idea that they were indigenous to the area where they lived – Etruria. This is the land north of the Tiber River, south of the Po River and west of the Apennine Mountains, comprising the present day Italian regions of Lazio, Tuscany and Umbria.

The Etruscan language was not written down until about 700 BCE when a modified Greek alphabet was used. What little we know, mainly from epitaphs on tombs and inscriptions on pottery, indicates a language that is not Indo-European in origin.

Without a history and with little language, our understanding of the Etruscans remains as fragmentary as the pottery in their graves. We piece together what we can.

In his prologue to The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (1962), Giorgio Bassani describes a visit to the Etruscan tombs at the Banditaccia Necropolis near Cerveteri (illustrated above). A young girl, Giannina, asks her father why it is that old tombs are not as sad as new ones. Her father suggests that

‘People who have just died are closer to us, and so we are fonder of them. The Etruscans, after all, have been dead for a long time’ — again he was telling a fairy tale — ‘so long it’s as if they had never lived, as if they had always been dead.’

Giannina thinks about this for a while and then replies

‘But now, if you say that,’ she ventured softly, ‘you remind me that the Etruscans were also alive once, and so I’m fond of them, like everyone else.’

Etruscans often evoke these tender feelings. This post, which follows a visit to Etruria last month in a tour led by Nigel Spivey, considers some aspects of Etruscan culture which have intrigued me. Like Giannina, I have become fond of them.

Eternal Banquets

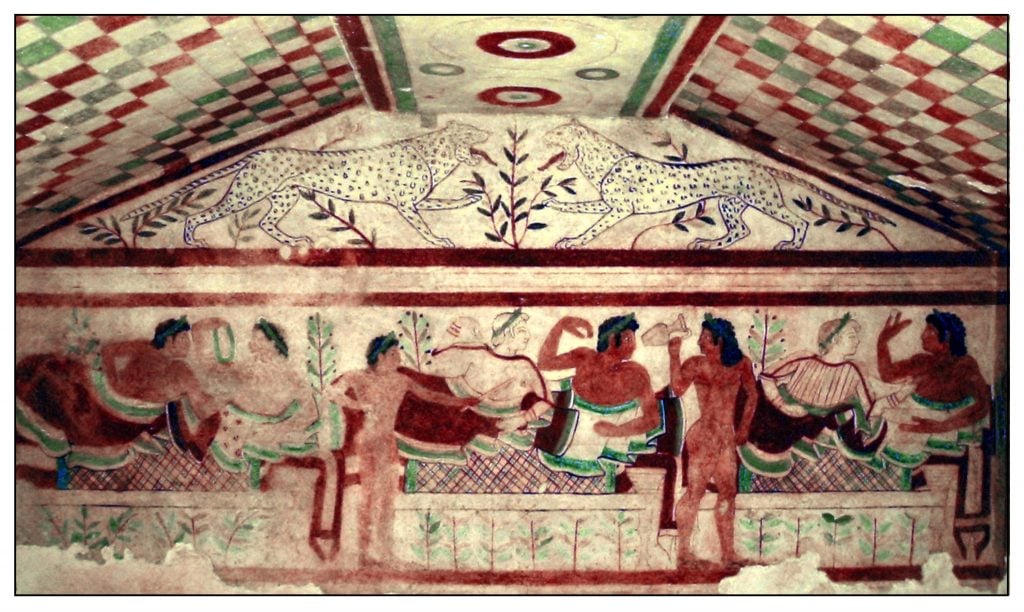

Most of what we know about the Etruscans come from their tombs. Their cities were destroyed and rebuilt by later civilizations, but the cemeteries remained largely untouched. Some tombs, especially those in the Monterozzi Necropolis near Tarquinia, have striking wall paintings. The Tomb of the Leopards from the 5th Century BCE (illustration below derived from Wikipedia) depicts a banquet (Tathje, 2013). Whether this represents the funeral celebration for the deceased or the eternal feasting to be expected in the afterlife is not known. Perhaps both.

D. H. Lawrence described this painting in Etruscan Places:

The end wall has a splendid banqueting scene. The feasters recline upon a checked or tartan couch-cover, on the banqueting couch, and in the open air, for they have little trees behind them. The six feasters are bold and full of life like the dancers, but they are strong, they keep their life so beautifully and richly inside themselves, they are not loose, they don’t lose themselves even in their wild moments. They lie in pairs, man and woman, reclining equally on the couch, curiously friendly. The two end women are called hetaerae, courtesans; chiefly because they have yellow hair, which seems to have been a favourite feature in a woman of pleasure. The men are dark and ruddy, and naked to the waist. The women, sketched in on the creamy rock, are fair, and wear thin gowns, with rich mantles round their hips. They have a certain free bold look, and perhaps really are courtesans.

The man at the end is holding up, between thumb and forefinger, an egg, showing it to the yellow-haired woman who reclines next to him, she who is putting out her left hand as if to touch his breast. He, in his right hand, holds a large wine-dish, for the revel.

The next couple, man and fair-haired woman, are looking round and making the salute with the right hand curved over, in the usual Etruscan gesture. It seems as if they too are saluting the mysterious egg held up by the man at the end; who is, no doubt, the man who has died, and whose feast is being celebrated. But in front of the second couple a naked slave with a chaplet on his head is brandishing an empty wine-jug, as if to say he is fetching more wine. Another slave farther down is holding out a curious thing like a little axe, or fan. The last two feasters are rather damaged. One of them is holding up a garland to the other, but not putting it over his head as they still put a garland over your head, in India, to honour you.

Above the banqueters, in the gable angle, the two great spotted male leopards hang out their tongues and face each other heraldically, lifting a paw, on either side of a little tree. They are the leopards or panthers of the underworld Bacchus, guarding the exits and the entrances of the passion of life. (Lawrence, 1933/1950, pp 65-66)

Lawrence enthusiastically conveys the feelings of the banquet. However, he did not get everything right. The tomb was constructed later than he thought and the women were likely not courtesans. Although the symposia of the Greeks involved only wine and were limited to males (and occasional courtesans), the feasts portrayed in Etruscan paintings included food and allowed both male and female participants. The relations between the sexes may have been more equal in Etruscan society than in other ancient cultures. Probably the most famous piece of Etruscan art is the Sarcophagus of the Spouses (6th century BCE) from Cerveteri, now displayed in the Villa Giulia in Rome. A married couple partakes of the eternal banquet. The man was probably holding in his right hand an egg as a symbol of regeneration. The woman may have held a small jar of oil to pour onto the outstretched hand of her husband. Their archaic smiles suggest an enviable serenity in the face of death:

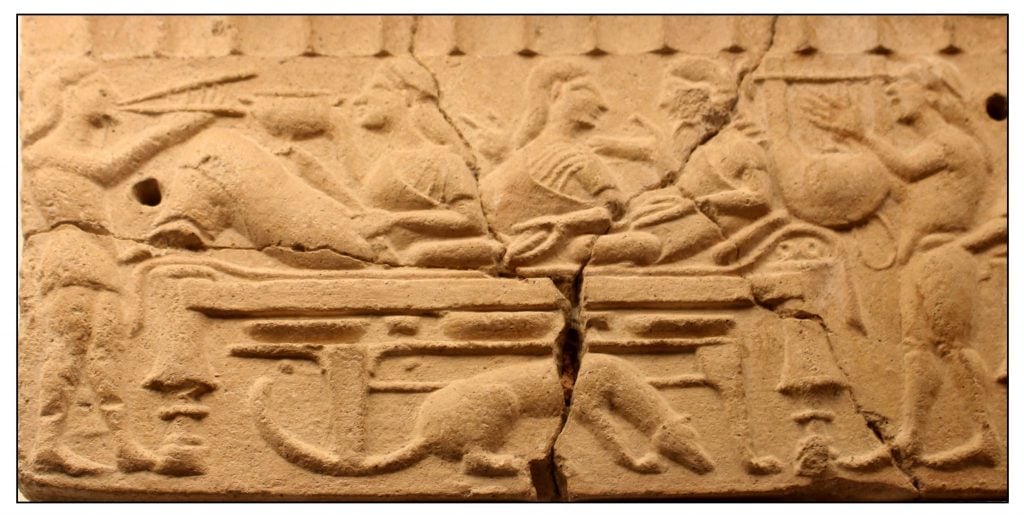

The banquet portrayed in tomb paintings and sarcophagi is a recurring theme in Etruscan art. The illustration below shows a fragment of a terra cotta frieze from the eaves of a temple. Three reclining Etruscans enjoy the music of the aulos on the left and the lyre on the right. Beneath the couch, the family pet scrounges for scraps of food:

The banquet portrayed in tomb paintings and sarcophagi is a recurring theme in Etruscan art. The illustration below shows a fragment of a terra cotta frieze from the eaves of a temple. Three reclining Etruscans enjoy the music of the aulos on the left and the lyre on the right. Beneath the couch, the family pet scrounges for scraps of food:

The painters and sculptors were either Greek immigrants to Etruria or Etruscans whom they had trained. The artists may have left Greece and came west because of war and tyranny in their homeland. In the middle of the 1st millennium BCE, large Greek colonies were founded in Sicily and Southern Italy. Although the Greeks did not colonize Etruria, they had extensive commercial and artistic interactions with the Etruscans.

In the first millennium BCE commercial shipping in the Mediterranean was very active: Phoenicians from both the Levant and Carthage, Greeks from both Greece and Sicily, and Etruscans all traded with each other (Bruni, 2013; Haynes, 2000, pp 62-64; Smith, 2014, chapter 5). Much of the trade involved luxury goods – wine, painted pottery, jewellery.

Afterlife

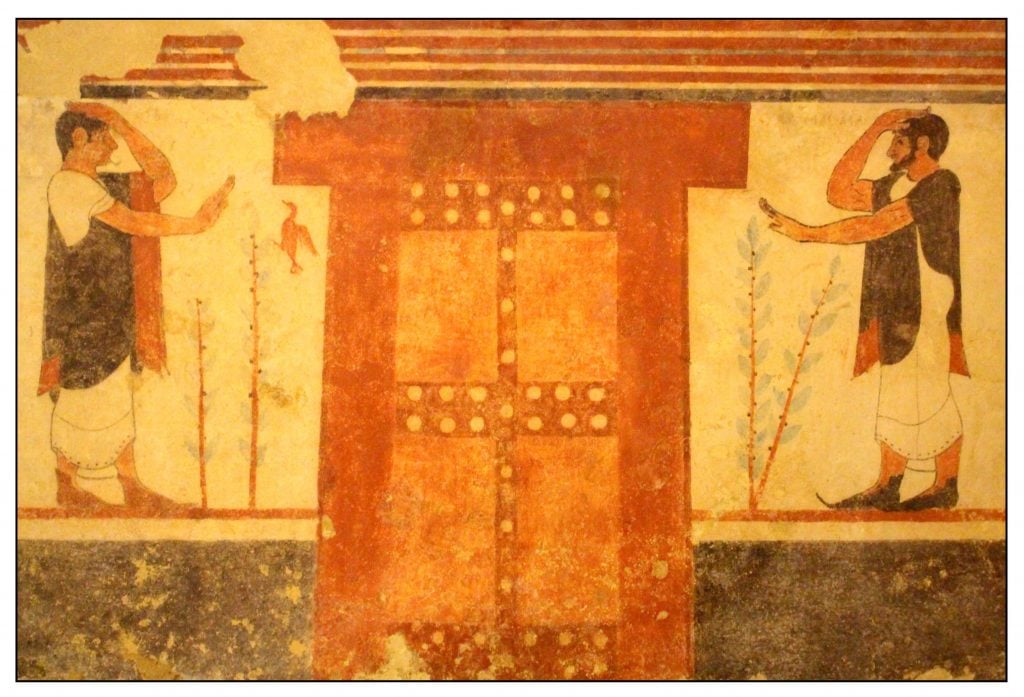

The central painting from the Tomb of the Augurs (6th century BCE) in Tarquinia shows a closed doorway (see below). This symbol, common in Etruscan funerary art and architecture, likely represents the portal between the realms of the living and the dead.

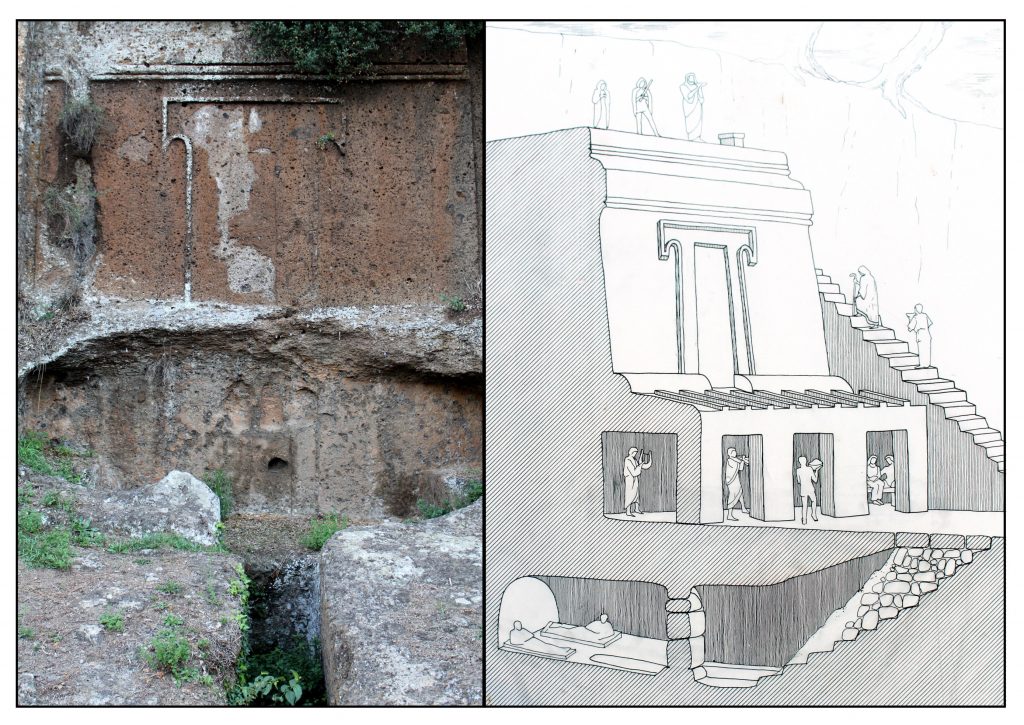

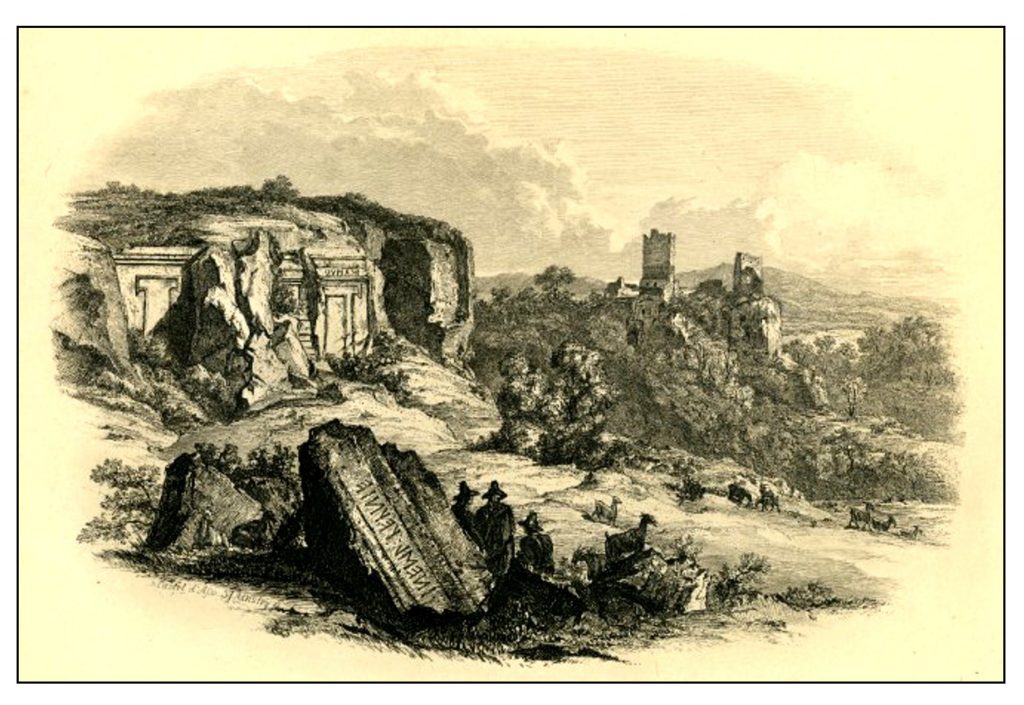

The symbol recurs in the ruined tombs in the tufa cliffs of the Castel d’Asso necropolis near Viterbo (see below). The tombs were designed on three levels (as diagramed on the right). The top allowed for sacrifices and libations to the gods. The middle level provided a place for the funerary celebrations, and the tombs containing the sarcophagi were below.

The ruins of the Castel d’Asso necropolis evoke the melancholy and mystery that the Victorians found fascinating in the Etrucans. Below is an etching (from British Museum) by Samuel Ainsley prepared for the 1848 book by George Dennis, Cities and Cemeteries of Etruria. Today the site remains little changed.

Divination

We are not sure what the two men standing on either side of the door in the Tomb of the Augurs are doing. Perhaps they are bidding farewell to the deceased who has gone beyond the door into the afterlife. Another interpretation, one that gives its name to the tomb, is that they are augurs foretelling the future through the flight of birds – auspicy. Indeed, a bird is seen on the left of the door.

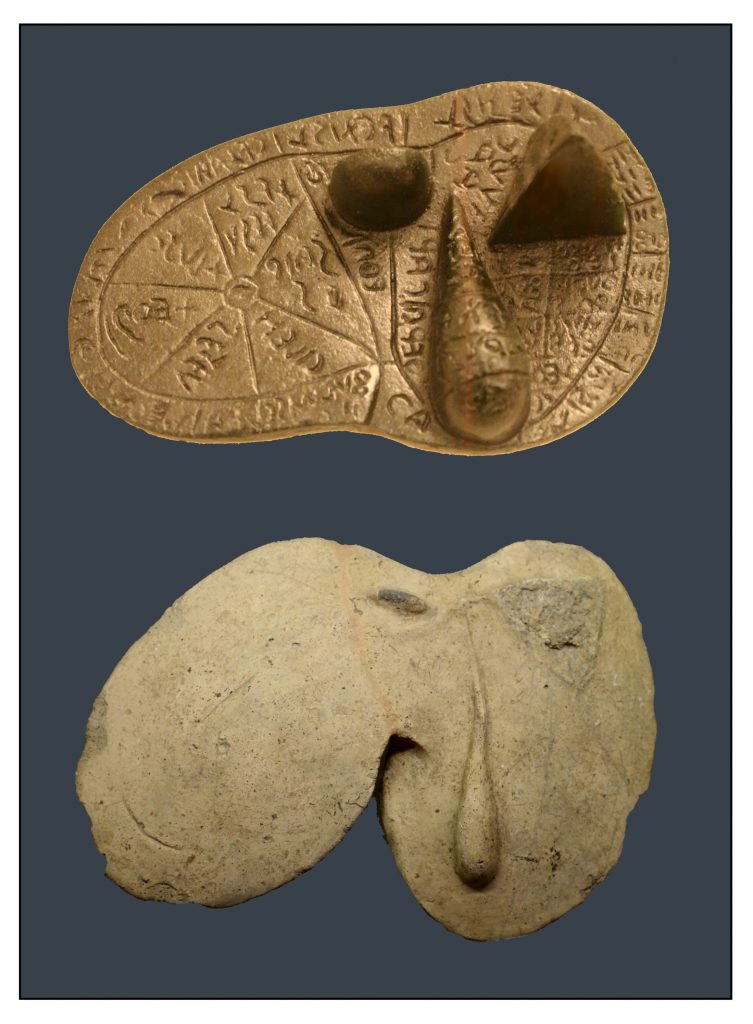

Etruscans also divined the future by examining the entrails of animals sacrificed to the gods – haruspicy (de Grummond, 2013). Etruscan graves have yielded fascinating models of the livers of sheep in bronze and in terra cotta (illustration on right). The bronze version (the Piacenza Liver) is extensively annotated to help guide the divination. The gall bladder droops down in the center; the caudate lobe is raised in the upper right, and the middle upper raised portion is likely the quadrate lobe.

Even during Roman times, Etruscans were renowned for their ability to foresee the future. The seer who warned Julius Caesar to beware the Ides of March was an Etruscan named Spurinna.

Portraits

Within the tombs, the Etruscan dead were usually placed within sarcophagi. Some of these were sculpted in terra cotta. The earlier sarcophagi – such as the Sarcophagus of the Spouses – have idealized features. Later versions of these sarcophagi present striking portraits of the deceased (Brendel & Serra, 1995, pp 387-400; Carpino. 2013). Greek sculpture tended toward the ideal, but later Etruscan sculpture was far more individual. The following illustrations show a sarcophagus from the 3rd or 2nd century BCE from Tuscania, and several portrait heads.

The tombs of the Etruscans were full of grave goods. These represented prestige objects or keimelia – “things which are to be treasured when plundered or presented, but not cashed in” (Spivey, 1997, p 43). Pottery was abundant. Although some of the pottery was made by Etruscans in imitation of the Greek forms, much of the pottery in the tombs came from Greece. The Etruscans traded with the Greeks for these beautiful objects. Athenian painted pottery was particularly popular, and many striking examples of these vessels were preserved in Etruscan graves. Indeed, most of the Athenian pottery in the British museum was actually found in Etruria rather than Greece.

Nevertheless, one type of pottery found in the graves – bucchero – was specifically Etruscan (Perkins, 2007; de Puma, 2013a). So much so that its presence elsewhere in the Mediterranean indicated trade with Etruria. The name bucchero is of uncertain origin. Some have linked it with a type of black clay from South America named bucaro in Spanish. Most of the Etruscan pottery was discovered in the tombs during the 18th century, a time when pottery from the New World was being imported to Europe, and the Spanish term may have become generalized to denote any balck pottery. Perhaps, a more reasonable suggestion is that the word might come from the Latin poculum for drinking cup.

Bucchero pottery is black or dark grey. Not just on the surface but throughout. The color was caused by decreasing the air supply to the kilns in which the pottery was baked. Due to the lack of oxygen, the iron in the clay became black ferrous oxide rather than red ferric oxide. The surface of bucchero can be burnished to an almost metallic sheen. Depending on the light the black surface sometimes has a faint tinge of brown or blue. Some have suggested that bucchero was made in imitation of more expensive bronze or silver vessels. Yet bucchero is beautiful in its own right.

The earliest bucchero made in the 7th and 6th centuries in the southern parts of Etruria. This thin-walled bucchero sottile was often engraved with simple geometric patterns such as spirals or fans. Later bucchero pesante with much thicker walls was manufactured in the 6th to 5th centuries BCE and was more common in northern Etruria. This type of bucchero was adorned with relief decoration. The following two wine pitchers (oenochoai) illustrate the differences. The decoration on the right pitcher shows a typical Etruscan image of flying horses.

One of the most characteristic styles of bucchero is the kantharos. The design of this particular type of wine vessel (below left) may have actually originated in Etruria. The high handles make the kantharos far easier to hold and drink from than the typical flat Greek kylix, which may have been more frequently used for libations rather than for drinking. The Etruscans also made elegant chalices (from Latin calyx) which are similar to our modern wine goblets. The illustration below shows a kantharos and a calyx from ancient Etruria.

Bronze mirrors were also common in the grave goods of Etruscan tombs from the 5th to 4th centuries BCE (de Puma, 2013bc). The backs of the mirrors were occasionally decorated with relief carvings, but more often they were engraved with drawings. These typically depicted persons from Greek mythology. In the illustrated mirrors below, the top two are very similar ̶ two nude men in the company of two women, one dressed and one not. This image occurs very frequently, and may have come from one particular workshop. Exactly who is represented varies. Sometimes the characters are actually labelled – as Achilles and Chryseis (Cressida) together with Helen and Paris (de Puma, 2013c, p 176). On other versions of this mirror, similar characters may be Castor and Pollux with Athena and Aphrodite (de Puma, 2013c, p 185).

These mirrors indicate a people highly conscious of themselves, aware of what it means to be beautiful and fascinated by stories. The polished side no longer reflects Etruscan faces but the drawings on the back preserve the contents of their imagination.

Envoi

D. H. Lawrence found in the Etruscans a vitality and honesty that he considered lacking in the modern world (Spivey, 1995, pp 192-194). He ignored the facts that Etruscan society existed on the backs of slaves, and that only the aristocrats were able to enjoy the good life. Lawrence saw what he wanted to see. We all do.

Nevertheless, it seems clear that the Etruscans enjoyed life immensely. Wine, music, beautiful things and good company were central to their lives. Most impressive was their intense self-consciousness. Their portraits and mirrors tell of people who sought to understand themselves. Their sense of self was deep enough to convince them that they would persist after death. We may not have the same beliefs. But we must admire this confidence.

References

Bassani, G. (1962, translated by W. Weaver, 1977). The garden of the Finzi-Continis. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Brendel, O., & Serra, R. F. R. (1995). Etruscan art. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bruni, S. (2013). Seafaring: shipbuilding, harbors, the issue of piracy. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 759-777). New York: Routledge.

Carpino, A. A. (2013). Portraiture. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 1007-1016). New York: Routledge.

de Grummond, N. T. (2013). Haruspicy and augury: Sources and procedures. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 539-556). New York: Routledge.

Dennis, G. (1848/1878). Cities and cemeteries of Etruria. 2nd Edition. Volume I and Volume II. London: John Murray.

de Puma, R. D. (2013a).The meanings of bucchero. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 974-992). New York: Routledge.

de Puma, R. D. (2013b). Mirrors in art and society. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 1041-1067). New York: Routledge.

de Puma, R. D. (2013c). Etruscan art in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Haynes, S. (2005). Etruscan civilization: A cultural history. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum.

Lawrence, D. H. (1933/1950). Etruscan places. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin.

Perkins, P. (2007). Etruscan Bucchero in the British Museum. British Museum Research Publication 165.

Smith, C. (2014). The Etruscans: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Spivey, N. J. (1997). Etruscan art. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Tathje, A. (2013). The banquet through Etruscan history. In J. M. Turfa (Ed.) The Etruscan World. (pp 823-830). New York: Routledge.