Gauguin

Gauguin

In 1891, Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) left his wife and five children and sailed for Tahiti, where he hoped

to immerse myself in virgin nature, to see no one but savages, live their life, with no other thought in mind but to render, the way a child would, the concepts formed in my brain and to do this with the aid of nothing but the primitive means of art, the only means that are good and true (letter quoted in Eisenman, 1997, p 77).

His decision to desert his family and follow his art has been considered by philosophers as a case study in ethics. Was his hope of artistic success adequate justification for his behavior? As luck would have it, Gauguin did become a famous artist, albeit posthumously. Can this retrospectively vindicate his flight to Tahiti? These issues are complex – both in the abstract and in terms of Gauguin’s actual life.

Life Before Art

Gauguin was born in France but spent much of his childhood in Peru, where his mother’s family had aristocratic connections. His grandmother Flora Tristan (1803-1844), a feminist and socialist, was the niece of Juan Pío Camilo de Tristán y Moscoso, who briefly served as president of South Peru.

Gauguin returned to France to finish his schooling and then spent three years as a merchant sailor and two years in the French Navy, during which time he travelled throughout the world. When he returned to France in 1871, Gauguin was taken in by a rich relative, Gustave Arosa, an avid collector of realist and impressionist paintings. Arosa got Gauguin a job on the stock exchange, and introduced him to Camille Pissarro.

Gauguin became a very successful broker, and took up painting as a hobby. He married a young Danish woman Mette-Sophie Gad (1850–1920), and had five children. Having made a fortune on the stock market, Gauguin became an art collector himself, buying paintings by Pissarro, Cézanne, Manet, Degas, and Sisley (Bretell & Fonsmark, 2005, p 56)

Impressionism

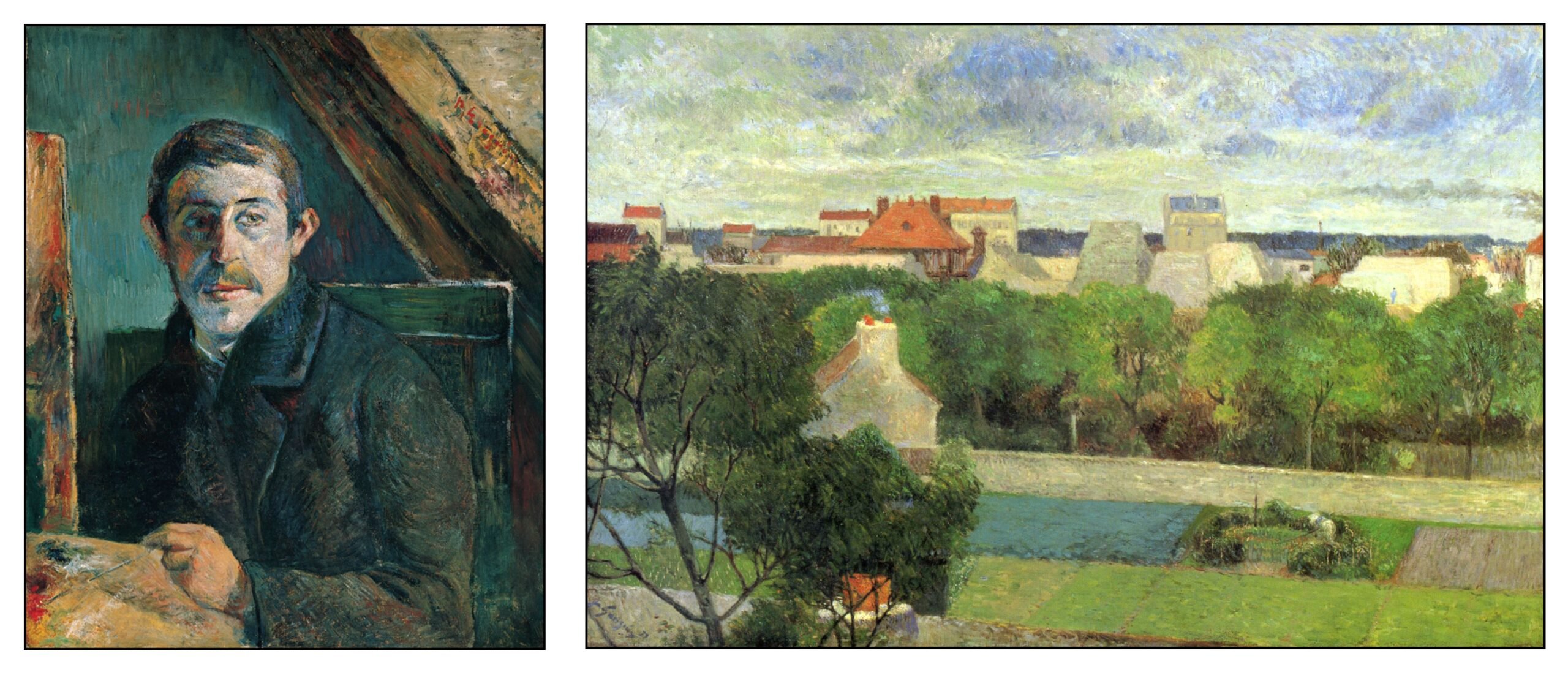

Gauguin had talent and he quickly learned the new Impressionist style. His paintings were included in the Impressionist Exhibitions beginning with the fifth in 1880. Below is one of his paintings from this time – Vaugirard Market Gardens, 1879 – together with a self-portrait from 1885.

The Stock Market Crash

In 1882 the Union Générale bank collapsed and the Paris Bourse crashed. By 1883 Gauguin was out of work. The family moved to Rouen where life was less expensive than in Paris. Gauguin decided to paint full time. However, he was not able to sell his paintings. Mette moved back to Denmark with most of the family in 1884, and Gauguin reluctantly followed in 1885. For a brief time, he was a salesman for French tarpaulins in Copenhagen, but he did not speak Danish and the endeavor came to nought. Mette supported the family by giving French lessons. Gauguin’s paintings found no market among the Danes. He became depressed, and sometimes was sometimes physically violent with his wife (Mathews, 2001, p 62). Mette’s family insisted that he leave.

In 1985 Gauguin returned alone to Paris. He submitted nineteen paintings to the Eighth and Final Exhibition of the Impressionist in1886, but these were not well received by either critics or buyers. Gauguin fled Paris for Pont-Aven in Brittany, an artists’ colony where living was cheap. There he worked with Emile Bernard and Louis Anquetin.

Vision after the Sermon (1888)

Gauguin was fascinated by the deep religiosity of the Breton peasants. He developed a new style of painting to portray their lives. He began using clearly outlined blocks of flat color in the manner of the Japanese prints that had become popular in Paris. He further decided that colors should be based as much upon the imagination as upon reality. This emphasis on the creative imagination derived from the Symbolist movement in literature. Gauguin named his new style of painting “Synthetism.” This approach was also called “Cloisonnism” after the technique for decorating metalwork, whereby colored enamels are placed within spaces bordered by metal strips. A masterpiece of this approach was Gauguin’s The Vision after the Sermon, which portrays Breton peasants experiencing a vision of Jacob wrestling with the angel after a sermon on this episode from Genesis 22: 22-32 (Herban, 1977):

The figure at the lower right is Gauguin. The young peasant at the lower left is likely a portrait of Bernard’s sister Madeleine, with whom Gauguin was infatuated. The following is a description of the painting from Vargas Llosa’s novel The Way to Paradise. Vargas Llosa used the second person narrative as though someone is talking to Gauguin (or Gauguin is talking to himself). “Koké” was the name that the Tahitians called him – their best approximation of his name:

The true miracle of the painting wasn’t the apparition of biblical characters in real life, Paul, or in the minds of those humble peasants. It was the insolent colors, daringly antinaturalist: the vermillion of the earth, the bottle green of Jacob’s clothing, the ultramarine blue of the angel, the Prussian black of the women’s garments and the pink-, green- and blue-tinted white of the great row of caps and collars interposed between the spectator, the apple tree, and the grappling pair. What was miraculous was the weightlessness reigning at the center of the painting, the space in which the tree, the cow, and the fervent women seemed to levitate under the spell of their faith. The miracle was that you had managed to vanquish prosaic realism by creating a new reality on the canvas, where the objective and the subjective, the real and the supernatural, were mingled, indivisible. Well done, Paul! Your first masterpiece, Koké! (Vargas Llosa, 2003, pp 217-218)

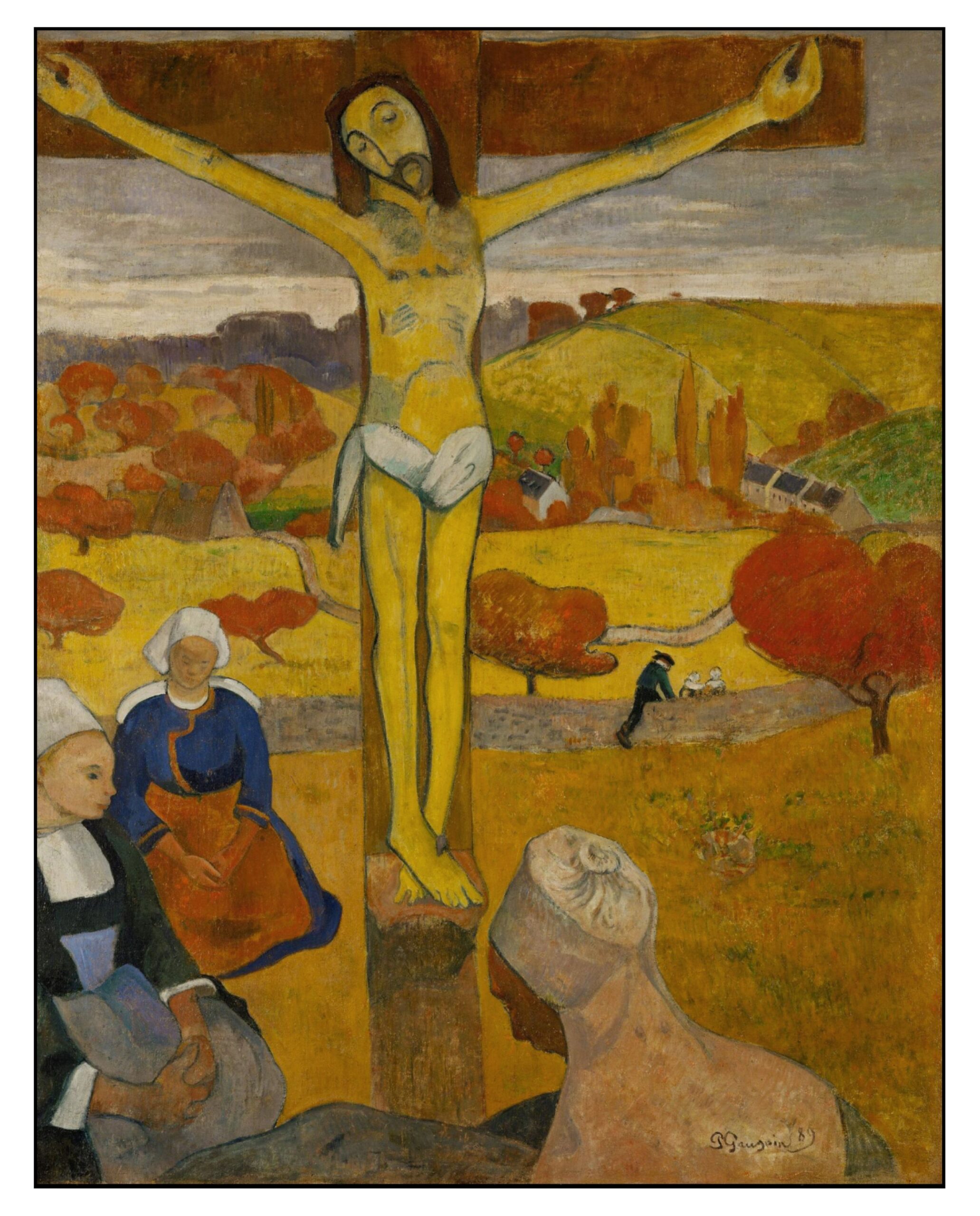

Gauguin also created a striking version of the crucifixion based on his time in Pont-Aven – The Yellow Christ (1889):

The Studio of the South

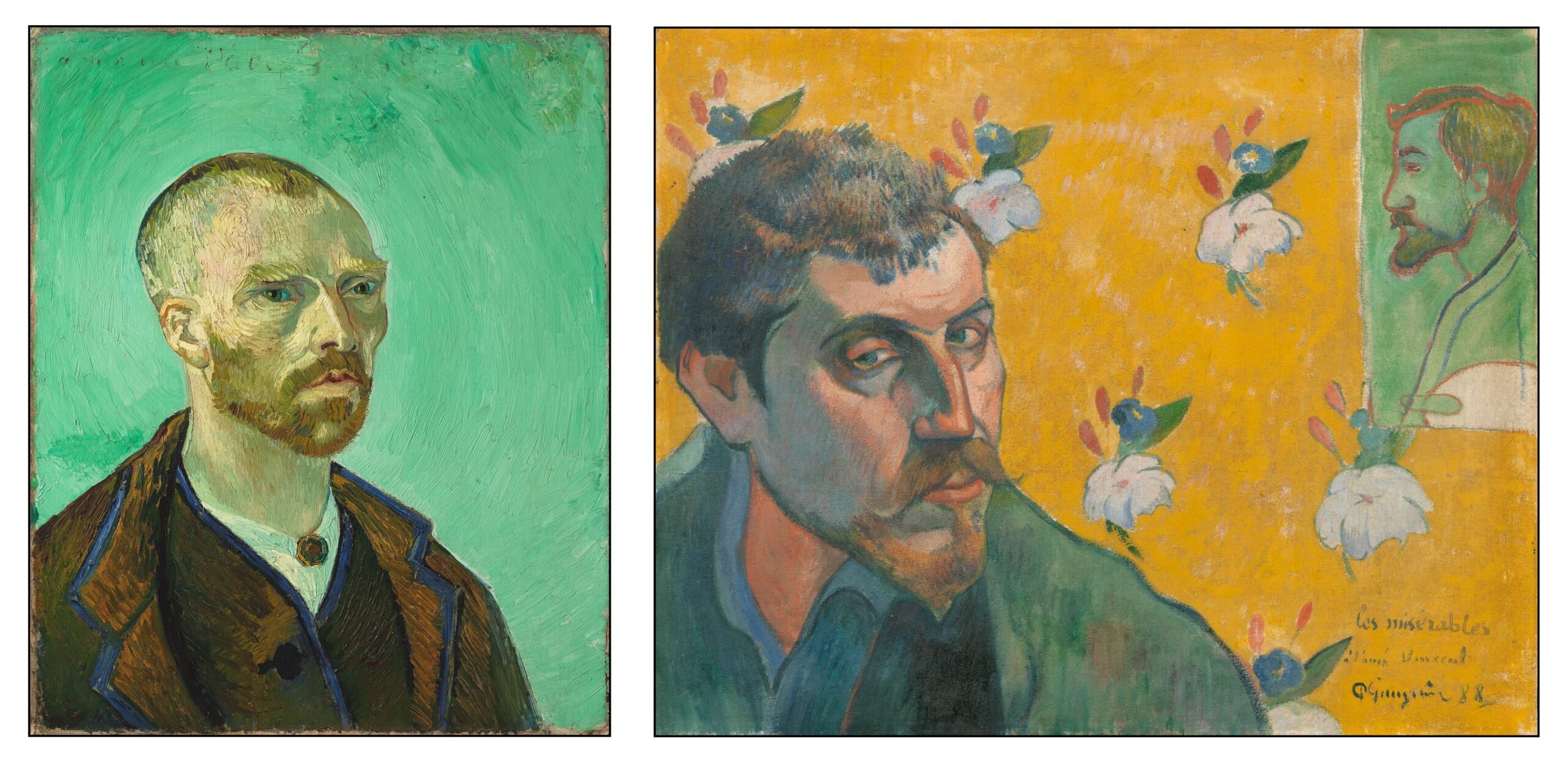

Back in Paris, Gauguin met the dealer Theo van Gogh and through him his brother Vincent. The two artists exchanged self-portraits. Van Gogh’s saw himself as an austere Japanese monk; Gauguin’s portrait is off-center against a floral wallpaper background includes a portrait of Emile Bernard:

Vincent invited Gauguin to stay with him in Arles in Provence. For nine weeks in late 1888 the two artists lived and worked together (Silverman, 2000; Druick et al, 2001). Although their relations were initially amicable, they disagreed on many things and the tension between them increased. If we are to believe what Gauguin later recalled in his journals (Gauguin, 2009, pp 12-14), one evening van Gogh threatened Gauguin with a razor and Gauguin decamped to stay the night in a hotel. Van Gogh then proceeded to cut off his right ear with the razor and presented the ear to one of the prostitutes in Arles. Gauguin fled to Paris and van Gogh was confined to an asylum.

Manao Tupapau

Van Gogh and Gauguin had discussed the book Rarahu by Pierre Loti (1880), which described the author’s marriage to a Tahitian girl, and the two artists considered the possibility of painting in the islands of the Pacific. Van Gogh committed suicide in 1890. Gauguin sailed to Tahiti in 1891.

In Tahiti Gauguin took a Tahitian girl aged thirteen, Tehemana (Tehura), as his mistress. One night when returning home late to his hut, he found her lying frightened on the bed:

Quickly, I struck a match, and I saw. . . . Tehura, immobile, naked, lying face downward flat on the bed with the eyes inordinately large with fear. She looked at me, and seemed not to recognize me. As for myself I stood for some moments strangely uncertain. A contagion emanated from the terror of Tehura. I had the illusion that a phosphorescent light was streaming from her staring eyes. Never had I seen her so beautiful, so tremulously beautiful. And then in this half-light which was surely peopled for her with dangerous apparitions and terrifying suggestions, I was afraid to make any movement which might increase the child’s paroxysm of fright. How could I know what at that moment I might seem to her? Might she not with my frightened face take me for one of the demons and specters, one of the Tupapaus, with which the legends of her race people sleepless nights? Did I really know who in truth she was herself? The intensity of fright which had dominated her as the result of the physical and moral power of her superstitions had transformed her into a strange being, entirely different from anything I had known heretofore. (Gauguin, 1919/85, pp 33-34)

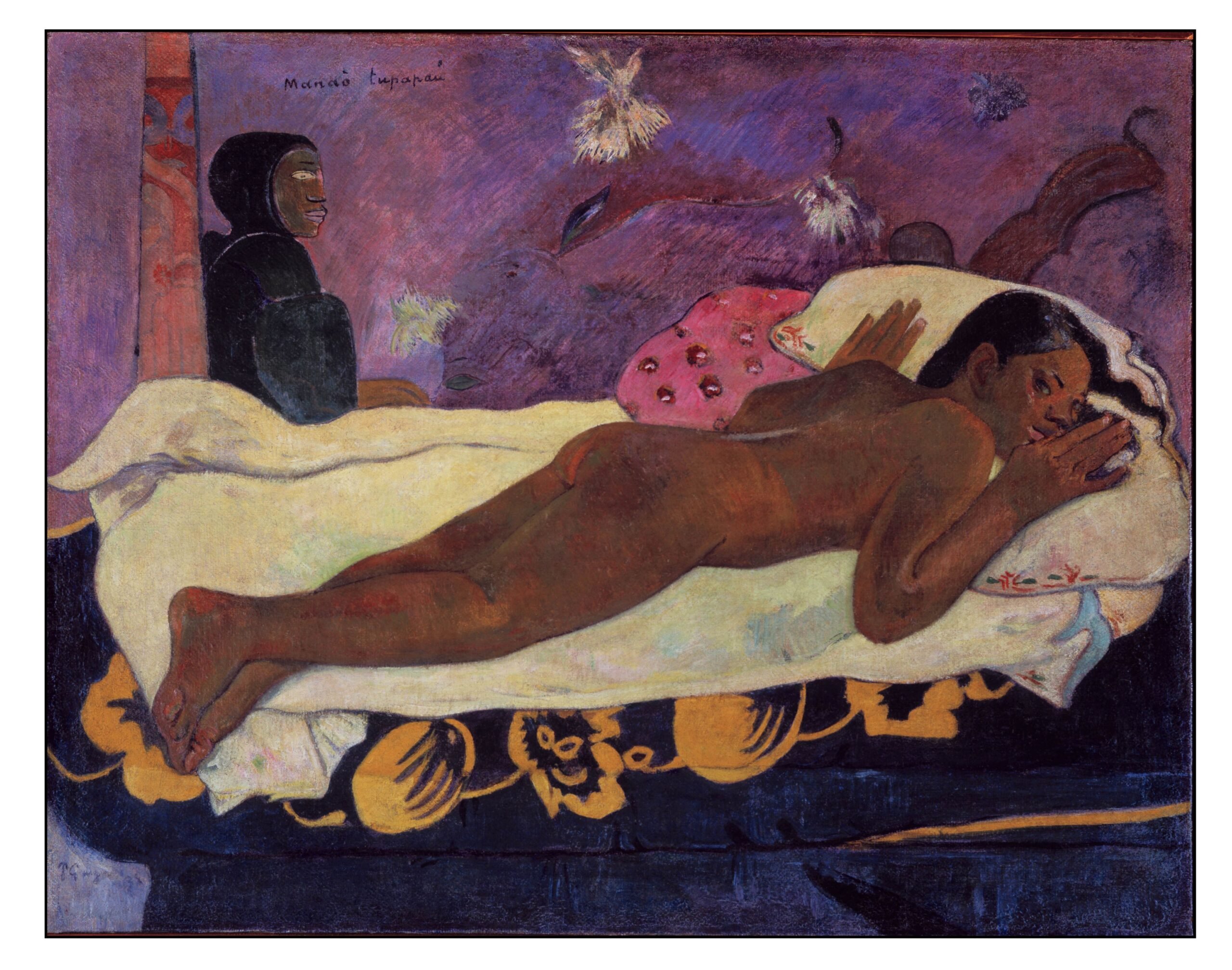

In Tahitian legends the Tupapaus were malignant demons. Over the next few days Gauguin painted the scene that he had witnessed, calling it Manao Tupapau, “Spirit of the Dead Watching” (1892):

Vargas Llosa imagines his thoughts about the painting:

Yes, this was truly the painting of a savage. He regarded it with satisfaction when it seemed to him that it was finished. In him, as in the savage mind, the everyday and the fantastic were united in a single reality, somber, forbidding, infused with religiosity and desire, life and death. The lower half of the painting was objective, realist; the upper half subjective and unreal but no less authentic. The naked girl would be obscene without the fear in her eyes and the incipient downturn of her mouth. But fear didn’t diminish her beauty. It augmented it, tightening her buttocks in such an insinuating way, making them an altar of human flesh on which to celebrate a barbaric ceremony, in homage to a cruel and pagan god. And in the upper part of the canvas was the ghost, which was really more yours than Tahitian, Koké. It bore no resemblance to those demons with claws and dragon teeth that Moerenhout described. It was an old woman in a hooded cloak, like the crones of Brittany forever fixed in your memory, time-less women who, when you lived in Pont-Aven or Le Pouldu, you would meet on the streets of Finistère. They seemed half dead already, ghosts in life. If a statistical analysis were deemed necessary, the items belonging to the objective world were these: the mattress, jet-black like the girl’s hair; the yellow flowers; the greenish sheets of pounded bark; the pale green cushion; and the pink cushion, whose tint seemed to have been transferred to the girl’s upper lip. This order of reality was counterbalanced by the painting’s upper half: there the floating flowers were sparks, gleams, featherlight phosphorescent meteors aloft in a bluish mauve sky in which the colored brushstrokes suggested a cascade of pointed leaves. The ghost, in profile and very quiet, leaned against a cylindrical post, a totem of delicately colored abstract forms, reddish and glassy blue in tone. This upper half was a mutable, shifting, elusive substance, seeming as if it might evaporate at any minute. From up close, the ghost had a straight nose, swollen lips, and the large fixed eye of a parrot. You had managed to give the whole a flawless harmony, Koké. Funereal music emanated from it, and light shone from the greenish-yellow of the sheet and the orange-tinted yellow of the flowers. (Vargas Llosa, 2003, pp 22-23)

The painting is one of the most discussed of Gauguin’s Tahitian pictures. The commentary is ambivalent:

All this is to put the painting in the best possible light. But there is surely more to it than just a charming anecdote based on local folklore. In blunt terms what we actually see is the interior of a hut at night, with a large couch, covered in a boldly flowered cloth, partially overlaid by a plain white sheet on which lies a naked girl, face down, another of the child-like, yet distinctly erotic figures who have appeared before in Gauguin’s work — pert buttocks offered invitingly to the spectator. There is even something disturbing about the way the face is half-turned towards the viewer, or rather towards the artist, Gauguin, as if he and not the figure in the background is the spirit of which she is afraid. (Sweetman, 1995, pp 326-327).

Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?

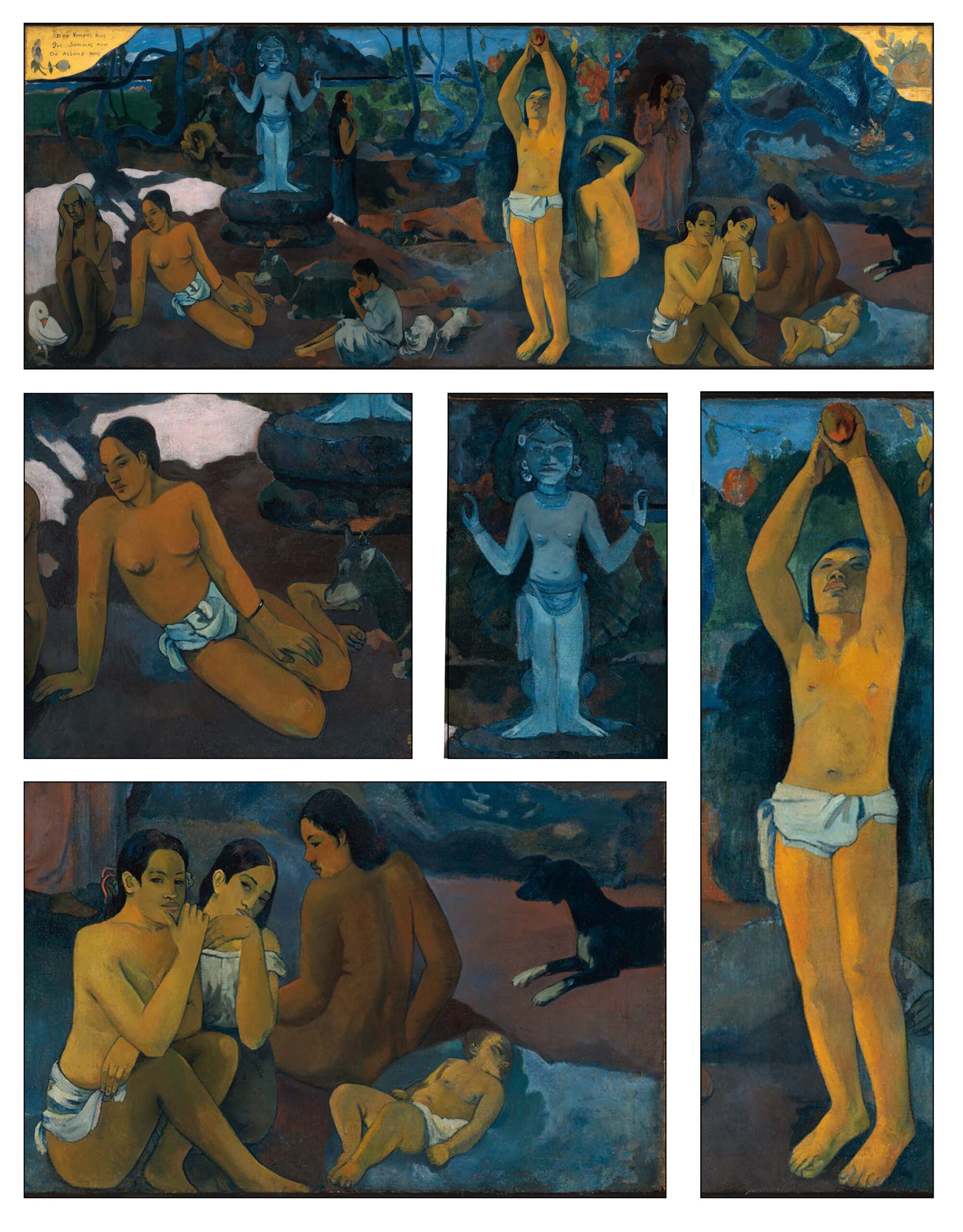

In 1893 Gauguin returned to Paris and arranged to sell some of his Tahitian paintings. He was not happy in Paris and in 1895 he returned to Tahiti. Over the next few years, Gauguin became severely depressed. He had suffered a broken ankle in a brawl in Concarneau near Pont Aven and the fracture had never really healed. He drank excessively – partly to relieve the pain and partly to improve his mood. He had sores on his legs, perhaps related to syphilis or perhaps related to the malnutrition that accompanies alcoholism. In 1897 he attempted to commit suicide with arsenic but failed. After this he worked on his last great painting, D’où venons-nous? Que sommes-nous? Où allons-nous? (1898):

Gauguin described his work in a letter to Daniel de Monfried:

The canvas is 4.50 meters long and 1.70 meters high. The two upper corners are chrome yellow, with the inscription on the left and my signature on the right, as if it were a fresco, painted on a gold-colored wall whose corners had worn away. In the bottom right, a sleeping baby, then three seated women. Two figures dressed in purple confide their thoughts to one another; another figure, seated, and deliberately outsized de-spite the perspective, raises one arm in the air and looks with astonishment at these two people who dare to think of their destiny. A figure in the middle picks fruit. Two cats near a child. A white she-goat. The idol, both its arms mysteriously and rhythmically uplifted, seems to point to the next world. The seated figure leaning on her right hand seems to be listening to the idol; and finally an old woman close to death seems to accept, to be resigned [to her fate]; . . . at her feet, a strange white bird holding a lizard in its claw represents the futility of vain words. All this takes place by the edge of a stream in the woods. In the background, the sea, then the mountains of the neighboring island. Although there are different shades of color, the landscape constantly has a blue and Veronese green hue from one end to the other. All of the nude figures stand out from it in a bold orangey tone. If the Beaux-Arts pupils competing for the Prix de Rome were told: “The painting you have to do will be on the theme, ‘Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?’ ” what would they do? I have finished a philosophical treatise comparing that theme with the Gospel. I think it is good. (Gauguin,1990, p. 160; original letter is illustrated in Shackelford & Frèches-Thory, 2004, p 168)

The philosophical treatise he mentioned was likely The Catholic Church and Modern Times (Gauguin, 1990, pp 161-173), in which Gauguin decries the hypocrisy of the modern church and urges his readers to return to a more natural theology. His painting is a testament to these ideas.

In a letter to Charles Morrice (Goddard, 2029, p 48) Gauguin describes his painting as proceeding from right to left, with the answer to “Where do we come from?” on the right, the answer to “What are we?” in the center and the answer to “Where are we going?” on the left. Nevertheless, the painting has no simple interpretation (Shackelford & Frèches-Thory, 2004, pp 167-201). The man plucking fruit from a tree in the center perhaps refers to Adam in a modern version of Eden. The two women in purple may refer to the church and its interpretation of our origins. The idol on the left is the Tahitian Goddess Hina (Gauguin, 1953, pp 11-13). Hina represented the sky, moon, air, and spirit. From the union between Hina and Tefatou, God of matter and earth, came forth man. Hina wished that man might be reborn after death much like the moon returns each month. Tefatou insisted that, although that matter lasts forever, man must die.

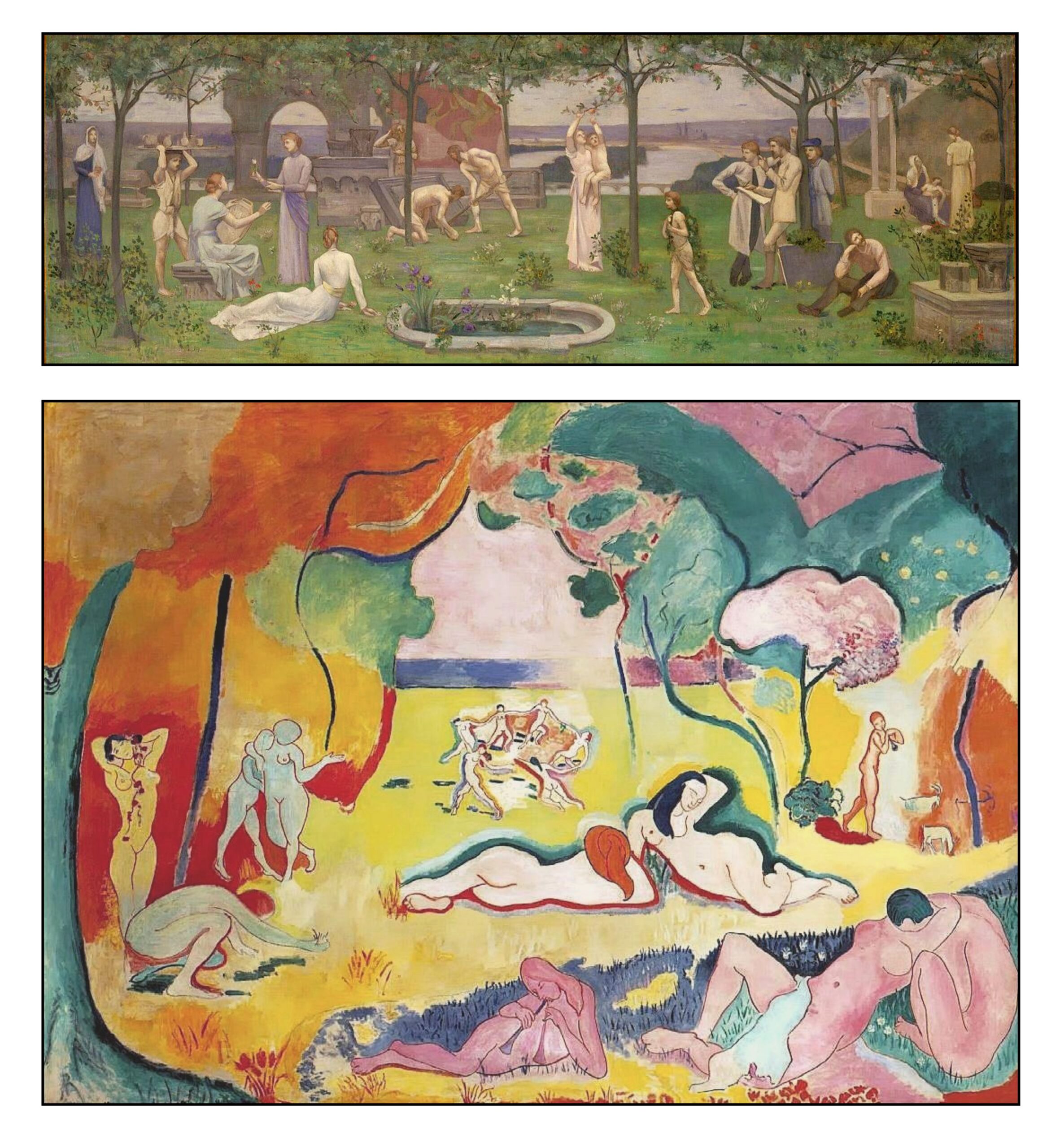

The painting stands at the cusp between earlier paintings like that of the neo-classical Between Art and Nature (1895) of Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, which Gauguin has seen on his visit back to Paris, and the Fauvist La Bonheur de Vivre (1905) of Henri Matisse. Both paintings are smaller than Gauguin’s masterpiece.

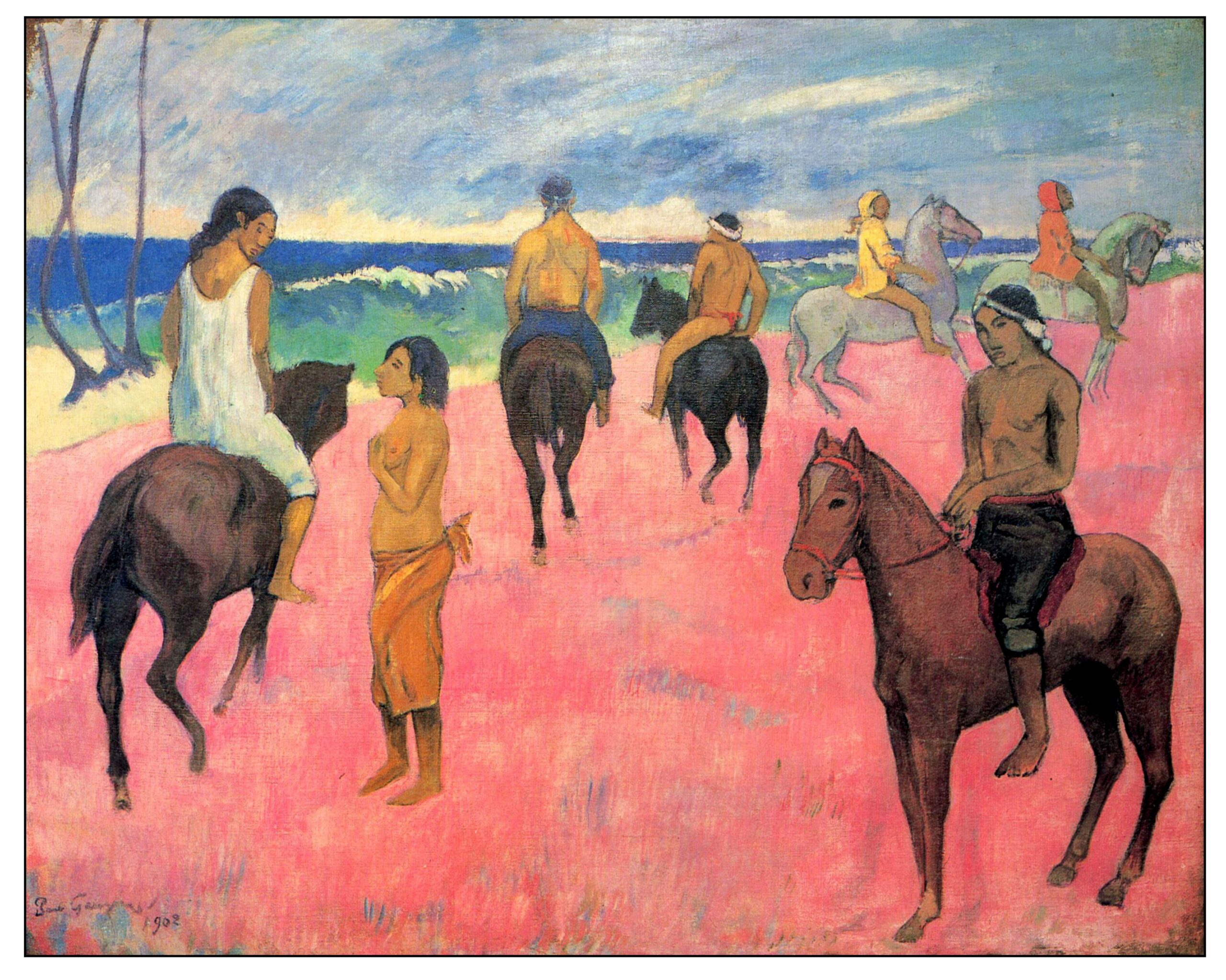

La Maison de Jouir

Gauguin decided that Tahiti was too tainted with Western civilization and decided in 1901 to move to the Marquesa Islands, about 1500 km northeast of Tahiti. There he again took a young Polynesian girl for his mistress and built himself a home that he called La Maison de Jouir. This is usually translated as the “House of Pleasure” but more precisely means the “House of Orgasm.” He continued to paint and to write, and he created many striking woodcuts and drawings. One of his paintings from 1902 was the Riders on the Beach. The pink color of the beach is in the imagination of the artist and nowhere near reality.

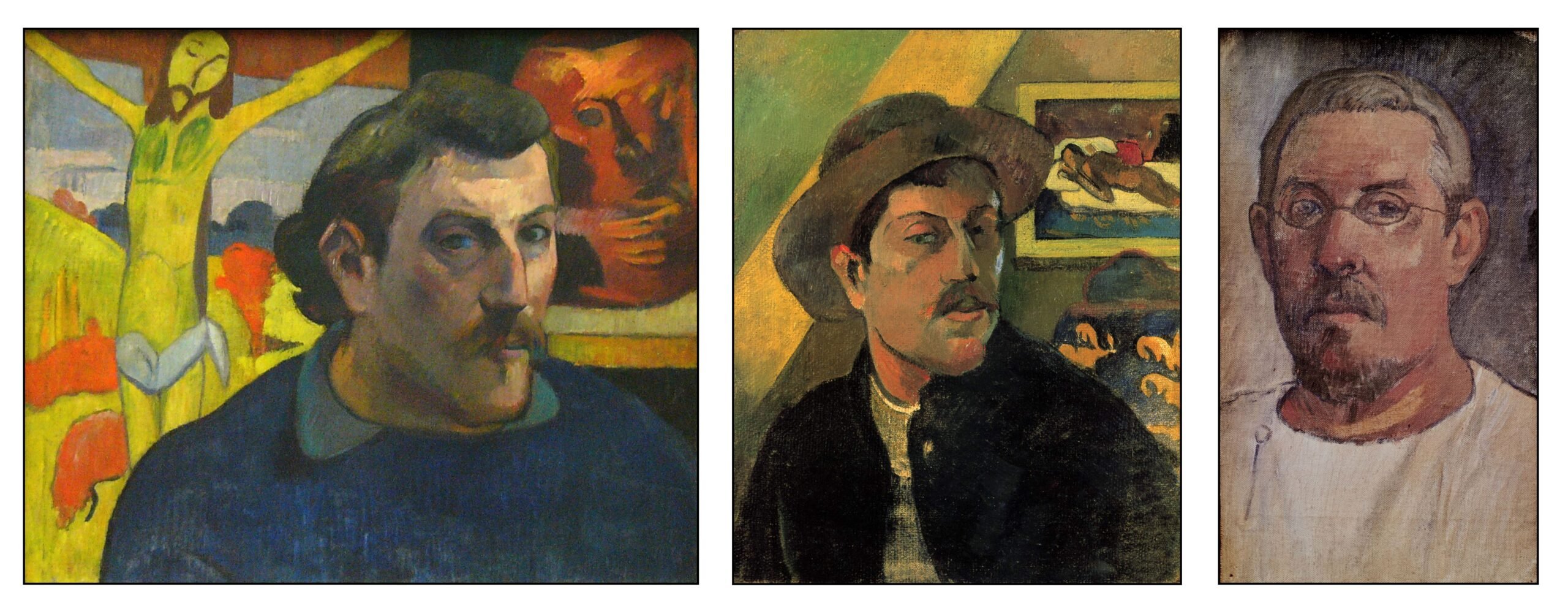

In these last years, Gauguin was wracked by pain and became more and more depressed. His last Self Portrait (1903) from just before his death shows the ravages of alcohol and morphine. It is presented below together with two earlier portraits, one from 1889 alluding to his time in Pont-Aven, and one from 1893 referring to his first visit to Tahiti:

Acclaim

Gauguin was never recognized in his lifetime as a painter of significance. His death in 1903 warranted only a few lines in the Paris newspapers. It was not until 1906 that his friends arranged a retrospective exhibition at the Salon d’Automne in Paris. His fame has grown since then. Art historians now consider Cézanne, van Gogh and Gauguin as the “guiding lights” (Hook, 2021, p. 21) of the modernist revolution in art that occurred in the first decades of the 20th Century. This assessment is borne out by the high prices that Gauguin’s paintings now command at auction.

Isabelle Cahn (in Shackelford & Frèches-Thory, 2004, pp 300-1) writes

He was the one who had dared take all the liberties, sparking the most advanced research, particularly in the domain of color . . . Gauguin had perceived the decline of the West and revolted against the dictatorship of Greco-Roman culture. In his wake, other artists had tried to surpass the traditional boundaries of thought and, seeking regeneration, had taken an interest in primitive arts, children’s drawings, folk art and outsider art. An interest in the unconscious had also opened new vistas. By giving shape to his internal world, Gauguin exposed the anxiety of the modern soul and its questions about its fate, leading us to edge of our own enigma, but not weighing it down with explanations.

Bretell (1988, p 396) remarks about the effects of Gauguin’s work on later painters:

Picasso was clearly devastated by the power and raw, crude strength of the printed drawings. Matisse was overcome by the color and the apparently casual draftsmanship of the late paintings. Indeed, if one can measure the strength of an artist by that of his most brilliant followers, Gauguin would be among the very greatest from the late nineteenth century.

Moral Luck

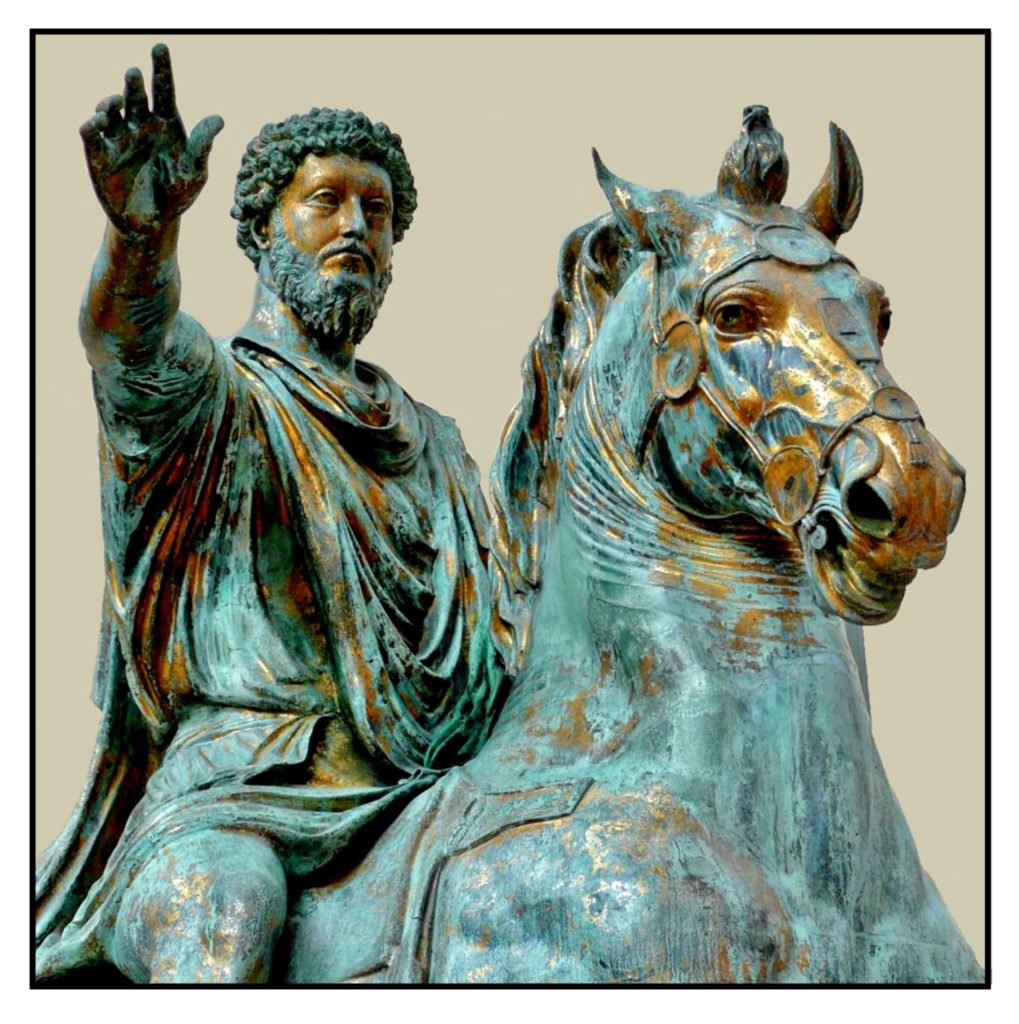

In 1976 Bernard Williams presented a paper on “Moral Luck,” in which he dealt extensively with the

example of the creative artist who turns away from the definite and pressing human claims on him in order to live a life in which, as he supposes, he can pursue his art.

For simplicity he calls the artist Gauguin, but he considers the case abstractly without being limited by historical facts. The main issue is that when Gauguin decided to desert his family, the only justification for his action was his hope that he would fulfil his destiny (and become a great artist), and that his art would contribute significantly to human culture. The concept of moral luck is that we cannot predict the future with any certainty. Gauguin may have died in a shipwreck before he reached Tahiti. In this event, his actions would have no justification. As chance (or “luck”) would have it, Gauguin did live to paint his greatest works in Tahiti, and did contribute significantly to the history of modern art. The problem is whether such an outcome can retrospectively justify the desertion of his family. Certainly not from the point of view of his family; probably not from the point of view of those with little interest in modern art. A secondary issue is whether aesthetic values can be used as justification for behavior that is, in itself, unethical.

Thomas Nagel commented on Williams’s ideas and discussed moral luck in a more general way. Both authors thereafter updated their papers (Nagel, 1979; Williams, 1981), and there has been much further discussion in the literature (e.g., Lang, 2019; Nelkin 2019). Nagel described moral luck as that which occurs between the intention to act and the outcome of the intended action. Though we might profess, like Kant, that moral guilt or acclaim depends upon the intension (or “will”) rather than the outcome, in actuality, the outcome largely determines our sense of an action’s moral worth. For example, a person who drives while impaired and winds up killing a pedestrian is considered much more blameworthy than one who was similarly impaired but, as luck would have it, did not kill anyone. Moral luck points to the issue that we do not completely control the outcomes of our actions.

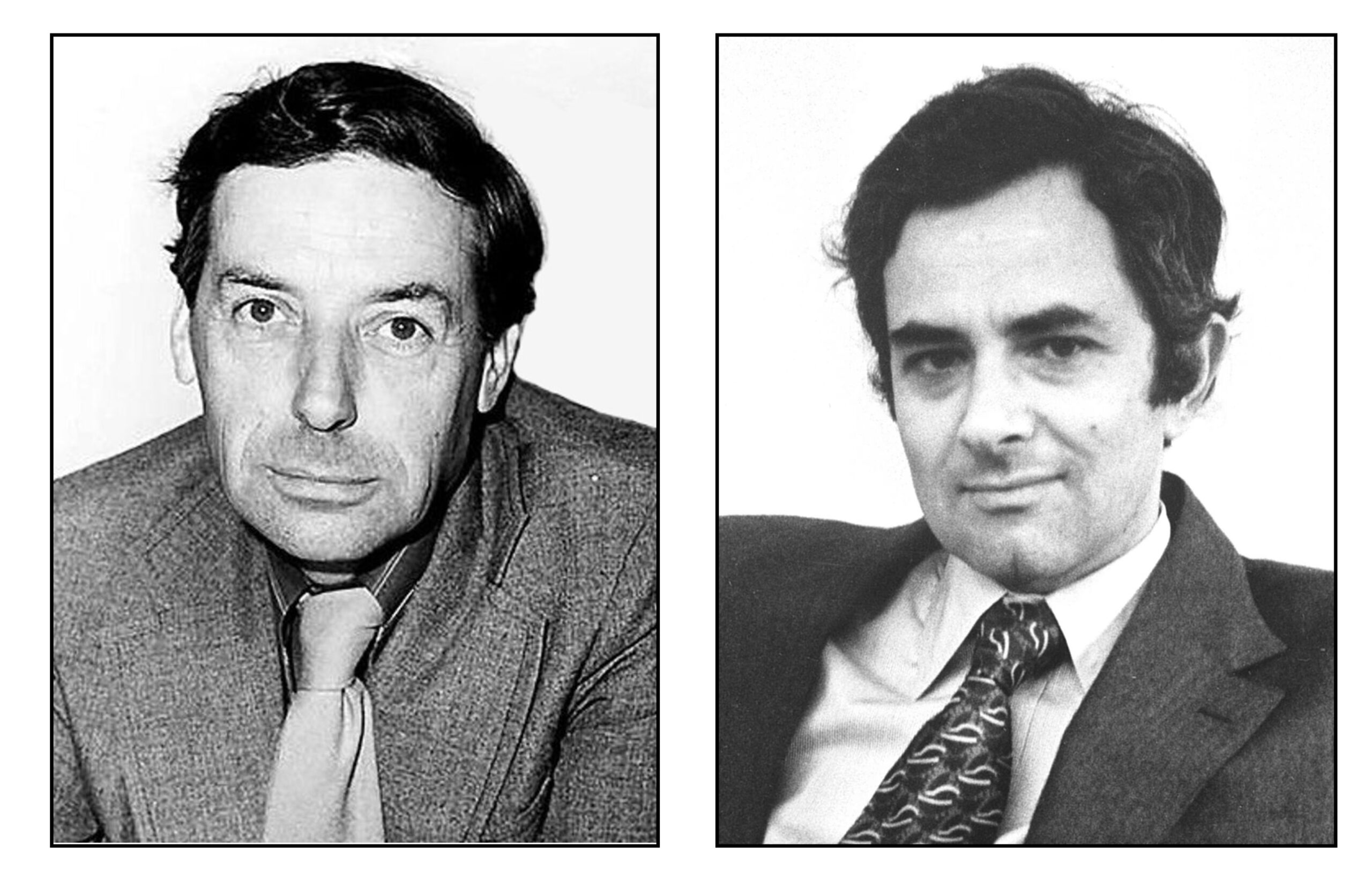

The following illustrations shows Williams on the left and Nagel on the right.

The Crimes of a Colonist

At the time of Gauguin’s sojourn, Tahiti and the Marquesas were French colonies. The administrators of the colonies exploited the native Polynesians; the church taught them that their own culture was worthless and that they must convert to Christianity; whatever was worthwhile in their life was appropriated and made part of European culture. It was impossible for Gauguin not to be part of this process – he was a European and French Polynesia was a colony. However, he did not act in the same way as most of the Europeans. He lived with the natives, and tried to understand their language and their ideas. He was aware of the problems:

Circumstances exposed him to the effects of recent colonization; he saw the depredation and the irrecoverable loss first-hand. He also spoke out about colonization – and thereby earned the animus of the colonial and church authorities who hounded him until the end of his life (Maleuvre, 2018).

Gauguin called the Polynesians “savages.” However, for him this was a term of praise rather than contempt. As quoted in the opening paragraph of this post, Gauguin aspired to become a savage.

Sex Tourist

Gauguin’s mistresses in Tahiti and in the Marquesas were young girls of 13 or 14 years. Although it was normal at that time for Polynesian girls of that age to have sexual relations with men, it is impossible not to deplore Gauguin’s taking advantage of them for his own sexual pleasure. Reading about these girls in his book Noa Noa (“Fragrance”) is terribly disconcerting:

Indeed, it is soon clear that he is not just the average Westerner exploring for the sake of broadening his understanding of the world—he is, more than anything, a sexual tourist. Even the title Noa Noa, which means “fragrance,” is used by Gauguin to indicate the aroma of a human body particularly in sexual situations. Although sexual liaisons similar to those described by Gauguin were regularly reported in other contemporary travel accounts, Gauguin makes them central to the story and, in doing so, transforms the normally pedestrian Tahitian sojourn into an erotic holiday. (Mathews, 2001, p 178).

Most historians believe that the sores on Gauguin’s legs and the heart problems that led to his death were caused by advanced syphilis. However, since the discovery of the causative agent (Treponema pallidum) and the definitive Wassermann test did not occur until after his death, we cannot be sure. A recent examination of Gauguin’s teeth did not show evidence that he had taken the mercurial compounds that normally were used to treat the disease at that time (Mueller & Turner, 2018). Nevertheless, the prevalence of syphilis then was high – about 10% in urban populations and likely much more in those who frequented prostitutes. If Gauguin did have syphilis, he almost certainly gave the disease to his young mistresses.

The following is from a poem Guys like Gauguin (2009) by Selina Tusitala Marsh. Louis Antoine de Bougainville was a French naval captain who explored the Pacific Ocean in the late 18th century:

thanks Bougainville

for desiring ’em young

so guys like Gauguin could dream

and dream

then take his syphilitic body

downstream to the tropics

to test his artistic hypothesis

about how the uncivilised

ripen like pawpaw

are best slightly raw

delectably firm

dangling like golden prepubescent buds

seeding nymphomania

for guys like Gauguin

The Artist as Monster

Gauguin as a person was not easy to like. He was concerned only with his own presumed genius. He treated his family and his mistresses egregiously. Does this mean that we should not consider his paintings – that he should be, in our modern idiom, “cancelled” (e.g., Nayeri, 2019)? Many artists have done monstrous things (Dederer, 2003), and it is often difficult to consider their art independently of their immoral lives. We should not shy away from their sins. We should not call Gauguin’s Polysnesian mistresses “young women” but clearly state that they were girls who were seduced by a sexual predator. Nevertheless, we must consider the art for its own sake. Gauguin’s paintings are powerful: they make us experience things differently.

References

Brettell, R. R. (1988). The Art of Paul Gauguin. National Gallery of Art.

Brettell, R. R., & Fonsmark, A.-B. (2005). Gauguin and Impressionism. Yale University Press.

Dederer, C. (2023). Monsters: a fan’s dilemma. Alfred A. Knopf.

Druick, D. W., Zegers, P., Salvesen, B., Lister, K. H., & Weaver, M. C. (2001). Van Gogh and Gauguin: the studio of the south. Thames & Hudson.

Eisenman, S. (1997). Gauguin’s skirt. Thames &Hudson.

Gauguin, P. (translated by O. F. Theis, 1919, reprinted 1985). Noa Noa: the Tahitian journal. Dover Publications.

Gauguin, P. (edited and annotated by R. Huyghe, 1951). Ancien culte mahorie. La Palme

Gauguin, P. (translated by E. Levieux and edited by D. Guérin, 1990). The writings of a savage. Paragon House.

Gauguin, P. (edited K. O’Connor, 2009) The intimate journals. Routledge.

Goddard, L. (2019). Savage tales: the writings of Paul Gauguin. Yale University Press.

Herban, M. (1977). The origin of Paul Gauguin’s Vision after the Sermon: Jacob Wrestling with the Angel (1888). The Art Bulletin, 59(3), 415–420.

Hook, P. (2021). Art of the extreme, 1905-1914. Profile Books.

Lang, G. (2019). Gauguin’s lucky escape: Moral luck and the morality system. In S. G. Chappell & M. van Ackeren (Eds.) Ethics Beyond the Limits. (pp. 129–147). Routledge.

Maleuvre, D. (2018). The trial of Paul Gauguin. Mosaic, 51(1), 197–213.

Marsh, S. T. (2009). Fast talking PI. Auckland University Press.

Mathews, N. M. (2001). Paul Gauguin: an erotic life. Yale University Press.

Mueller, W. A., & Turner, C. B. (2018). Gauguin’s Teeth. Anthropology, 6: 198.

Nagel, T. (1979). Moral Luck. In Mortal Questions. (pp. 24–38) Cambridge University Press.

Nayeri, F. (November 18, 2019). Is it time Gauguin got canceled? New York Times.

Nelkin, D. N. (2019) Moral Luck. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Silverman, D. (2000). Van Gogh and Gauguin: the search for sacred art. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Shackleford, G. T. M., & Frèches-Thory, C. (2004). Gauguin Tahiti: the studio of the South Seas. Thames & Hudson.

Sweetman, D. (1995). Paul Gauguin: a life. Simon & Schuster.

Vargas Llosa, M. (translated by N. Wimmer, 2003). The way to paradise. Farrar Straus & Giroux.

Williams, B. A. O. (1981). Moral Luck. In Moral Luck: Philosophical Papers 1973-1980. (pp. 20–39) Cambridge University Press.

Williams, B. A. O., & Nagel, T. (1976). Moral Luck. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volume, 50(1), 115–151.