Sub Regno Cynarae

Ernest Dowson was born in 1867 into a prosperous family in London. His father owned a dock, but had more interest in literature than in business. Ernest spent two and a half years at Oxford, but he did not take a degree, leaving in 1888. The dock fell into debt, and the family became poor. His father took his own life in 1894, his mother following suit a few months later. Ernest Dowson became a homeless, alcoholic poet. He consorted with prostitutes. His most famous poem recalls the shadow of an earlier love:

Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae

Last night, ah, yesternight, betwixt her lips and mine

There fell thy shadow, Cynara! thy breath was shed

Upon my soul between the kisses and the wine;

And I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, I was desolate and bowed my head:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

All night upon mine heart I felt her warm heart beat,

Night-long within mine arms in love and sleep she lay;

Surely the kisses of her bought red mouth were sweet;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

When I awoke and found the dawn was gray:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale lost lilies out of mind;

But I was desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, all the time, because the dance was long:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

I cried for madder music and for stronger wine,

But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire,

Then falls thy shadow, Cynara! the night is thine;

And I am desolate and sick of an old passion,

Yea, hungry for the lips of my desire:

I have been faithful to thee, Cynara! in my fashion.

The Latin quotation is from Horace’s Ode IV:1: “I am not the same as when I was ruled by the good Cynara.” Dowson was very familiar with the Roman poets. Although he did not finish his degree, he had distinguished himself in Latin in his years at Oxford.

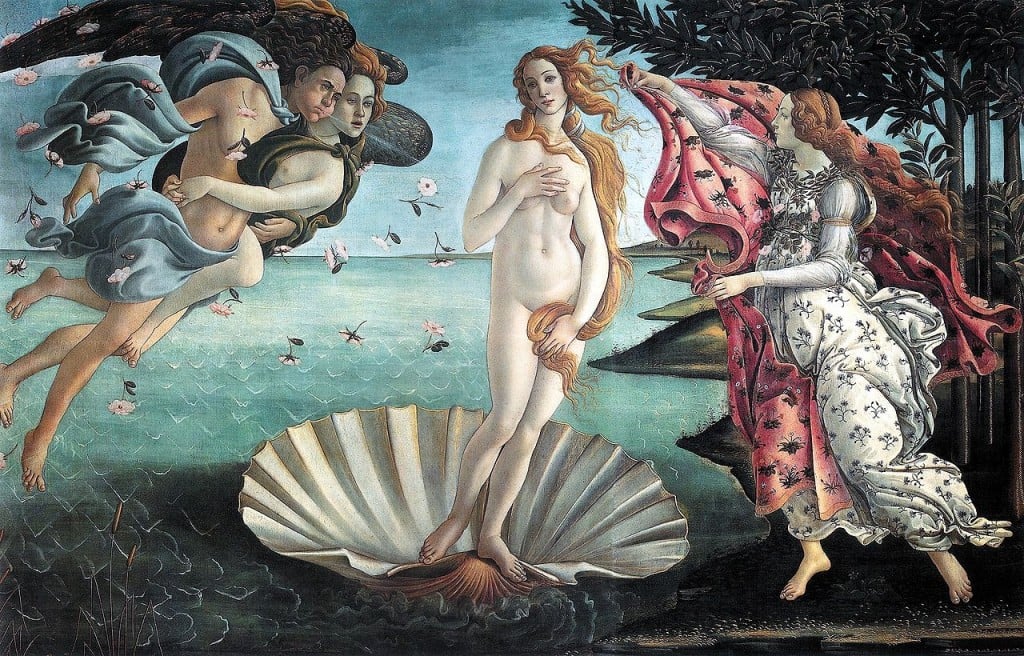

The subject of Horace’s ode is not the same as that of Dowson’s poem. Horace is asking Venus to have mercy on him and not to tempt him with new passions, now that he is in his fifties and not the man he was. He tells Venus to attend to the prayers of younger and more able lovers. Yet he is unable to stop the tears and tongue-tied state brought on by thoughts of their present loves and remembrance of his past. His erotic stumbling has run alongside a creative slowing, ten years having passed since the Horace’s last book of poems. The ode thus concerns his creative as well as his amorous activities – Cynara was his muse as well as lover (Putnam, 1986).

Furthermore, a sense of impending death edges his new poems. Horace was to die in the year 8 B.C. at the age of 57. Horace’s most famous poem Diffugere neves is the seventh ode in this fourth book: “Who knows whether the high Gods will add more tomorrows to the sum of our todays?” (translation Shepherd). Nevertheless, different though they are, both Horace’s ode IV:1 and Dowson’s poem tell of the passage of youth and ability, and the shadow of the past that falls between the present moment and its enjoyment.

Cynara was a quondam mistress of Horace. She is referred to only occasionally in his poems and the letters. She is described as mischievous (proterva) and greedy (rapax). Horace remembers that in his youth he must have been both very handsome and very eloquent to have charmed Cynara “without a present” (Radice, in introduction to Horace, 1983, p.34). She died young. In Ode IV:13, Horace remarks cruelly on the aging of her successor Lyce: “To Cynara, the fates allowed few years, but Lyce shall be long preserved, an aged crow.” It is not clear whether Cynara left Horace before she died. My intuition is that she did and that his “sad laments” at her leaving combined both real mourning and the bitterness of a rejected lover.

The actual situation in Dowson’s poem shows more similarity to the relations between Propertius, another Augustan poet, and his mistress Cynthia (Benediktson, 1989). As Plarr (1914, p.57) succinctly states in his reminiscences about Dowson’s poem: “Horace suggested, but Propertius inspired.” Cynthia and Propertius experienced both high passion and extreme jealousy, being most in love when they were unfaithful to each other. In Propertius’ last book of odes, he describes how he retaliated after Cynthia had deceived him: with Phyllis and with Teia “we scattered simple roses for their scent … they sang: I was deaf; showed their breasts: I was blind” (IV:8, translation Shepherd). Suddenly Cynthia returned, furiously putting Phyllis and Teia to flight, fumigating the bed, and making passionate love to Propertius.

In perhaps the most striking of his poems (IV:7), Propertius describes receiving a visit from Cynthia’s ghost after he had witnessed her cremation. The ghost remembers their “secret promises”, swears “I kept my faith to you” and prophecies that “though others may possess you, later I shall hold you alone and clutching closely, bone to bone.” (translation Highet, 1965). Indeed, one wonders whether the jealous Cynthia described in Ode IV:8 returned in mortal or immortal form.

Dowson’s Cynara poem conveys the same feelings as Propertius’ Cynthia poems, though the details of the visits differ. In Propertius, Cynthia is specifically described as the shadow, whereas in Dowson Cynara casts a shadow; in the Latin, it is Cynthia and not the poet who keeps the faith, and keeps it even beyond her death.

Dowson’s poem describes a terrifying nostalgia. His 1896 book of poems was dedicated to Adelaide Foltinowicz, the daughter of the owner of a small restaurant in London. Her youth and innocence had completely fascinated him. He called her “Missie,” and asked for her hand in marriage. Yet Dowson’s passion came to naught: “she listened to his verses, smiled charmingly, under her mother’s eyes, on his two years’ courtship, and at the end of two years married the waiter instead” (Symons in introduction to Dowson’s poems, 1905, p xiii).

In 1897, Adelaide married Auguste Noelte, a tailor who helped out in her father’s restaurant. Dowson was devastated. He fell into a life of dissipation. His problems with alcohol had started before Adelaide’s refusal, and may indeed have led to Adelaide’s favoring some one less wild. Dowson was not without insight. He realized that his passion was irrational and that he and his beloved were not suited to each other. In a later poem To a Lost Love he says, “But at the best, my dear, I see we should not have been very near.” However, this poem is not memorable: reason does not have the same rhythmic drive as passion, and often fails to persuade.

The poem to Cynara, however, is technically brilliant. The repetition gives a strong slow rhythm to the poem like the tolling of a bell. Since the two repeating lines of each verse are separated by a new line, this rhythm is gained without loss of interest. Even within the repetition, there is novelty: “and” varies to “but” and back, and the final verse uses the present tense – “I am desolate and sick.” The images are balanced: “her warm heart” goes with “her bought red mouth” and “riotous roses” with “pale lost lilies.” The sounds provide musical accompaniment to the images: the lilting l, m and n sounds of the line “Night-long within my arms in love and sleep she lay,” and the softly dying s and f sounds of “But when the feast is finished and the lamps expire.”

The Cynara poem is probably not directly related to Adelaide since it was written in 1891 when Dowson had only just met her (a girl of twelve) and long before she decided to marry another. The poem is perhaps more related to the inevitable loss of innocence and beauty voiced by Horace and Propertius. Given Dowson’s life, it is also tempting to see in it the loss of his own art and potential.

In 1890, William Butler Yeats and Ernest Rhys had started The Rhymers’ Club, a small group of poets that met irregularly in a tavern just off Fleet Street called The Cheshire Cheese (Alford, 1994). The poets would have supper and then adjourn to the upper room of the pub to read and discuss their poetry. They published two volumes of the Book of the Rhymers’ Club in 1892 and 1894. The Cynara poem, initially published in The Hobby Horse in April, 1891, was reprinted in the second book (p. 61).

Among the members of The Rhymers’ Club were Lionel Johnson, Arthur Symons, Victor Plarr, Francis Thompson, Richard La Gallienne and Ernest Dowson. Oscar Wilde joined them occasionally. These were the English “decadents.” They followed the precepts of Walter Pater and pushed the ideal of art for art’s sake to its emotional limits. The poets played with dissipation, much like Baudelaire in France three decades before. “I cried for madder music and for stronger wine” is in the vein of Baudelaire’s prose poem Enivrez-Vous (Be Drunken):

Be always drunken. Nothing else matters: that is the only question. If you would not feel the horrible burden of Time weighing on your shoulders and crushing you to the earth, be drunken continually.

Drunken with what? With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you will. But be drunken.

And if sometimes, on the stairs of a palace, or on the green side of a ditch, or in the drear solitude of your own room, you should awaken and the drunkenness be half or wholly slipped away from you, ask of the wind, or of the wave, or of the star, or of the bird, or of the clock, or whatever flies, or sighs, or rocks, or sings, or speaks, ask what hour it is ; and the wind, wave, star, bird, clock, will answer you: “It is the hour to be drunken ! Be drunken, if you would not be martyred slaves of Time; be drunken continually! With wine, with poetry, or with virtue, as you will.” (Baudelaire 1869, translated by Symons, 1905)

In his memoirs, Yeats (1972, p. 93) described Dowson as “burning to the socket, in exquisite songs celebrating in words full of subtle refinement all those he named with himself ‘us the bitter and gay’.” The quotation is from the Villanelle of the Poet’s Road

Wine and woman and song.

Three things garnish our way

Yet is day over long

Lest we do our youth wrong

Gather them while we may

Wine and woman and song.

Three things render us strong

Vine leaves, kisses and bay

Yet is day over long.

Unto us they belong

Us the bitter and gay

Wine and woman and song.

We, as we pass along

Are sad that they will not stay

Yet is day over long.

Fruits and flowers among

What is better than they:

Wine and woman and song?

Yet is day over long.

Dowson tried to live the life proposed by Walter Pater: “to burn always with this hard, gem-like flame, to maintain this ecstasy, is success in life” (Pater, 189, p. 188). Yet for the cultivated hedonism of Pater, Dowson substituted wine and women. He was drunk more than sober, slept with prostitutes, and got himself into drunken brawls with laborers and cabmen. He burned himself out.

Dowson’s poem to Cynara has exerted an immense impact on the culture of the twentieth century. Quotations from the poem show up in the titles of books and movies, and in popular songs. T. S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men (1925) echoes the anxiety of the shadow:

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

For Thine is the Kingdom

Between the conception

And the creation

Between the emotion

And the response

Falls the Shadow

Life is very long

Between the desire

And the spasm

Between the potency

And the existence

Between the essence

And the descent

Falls the Shadow

For Thine is the Kingdom

Dowson used another quotation from Horace as the title of the first poem in his 1896 book. Horace was well loved of the English, particularly in the 19th century. His was a gentleman’s poetry, full of wisdom and restraint, clear-headed and elegant. His sense of beauty was tempered with irony. Horace lived when Roman Empire was at its zenith, much like the British Empire in the time of Queen Victoria. Just as the Romans looked back to Greece, so did the English look back to Rome to see how to live properly. Dulce et decorum est pro patriae mori (Ode III:2 – It is sweet and fitting to die for your country) and Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero (Ode I:11 – Seize the day, and put little trust in the morrow) were Horace’s gifts to England. In both England and Rome, the enduring nature of the empire brought thoughts of the ephemerality of the individual. Keats translated Horace’s fourteenth epode to begin his own Ode to a Nightingale. Dowson’s poem also deals with the brevity of our life:

Vita summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam

They are not long, the weeping and the laughter,

Love and desire and hate:

I think they have no portion in us after

We pass the gate.

They are not long, the days of wine and roses:

Out of a misty dream.

Our path emerges for a while, then closes

Within a dream.

The quotation is from Horace’s Ode I:4: “Life’s short span forbids us to entertain long-term hopes.” Dowson’s poem is quoted by Edmund, the younger son, in Long Day’s Journey into Night (O’Neill, 1955, p. 130). The stage directions state “sardonically.” His father rails against such morbidity. Edmund goes on to bait his father further with Baudelaire’s “Be always drunken” (p. 132). Eugene O’Neill was well aware how seductive these ideas were, how easy it was to fall into the life of intoxication and oblivion, where talent is wasted and hopes washed away in the beauty of what might have been.

Dowson did indeed waste away. After being rejected by Adelaide, he moved to France, where he eked out a living writing translations. He suffered from severe poverty, alcoholism, and tuberculosis. He returned to London in late summer of 1899, and finally succumbed on February 22, 1900. Yeats wrote to Lady Gregory, “Poor Dowson is dead. Since that girl in the restaurant married the waiter he has drunk hard and so gradually sank into consumption. It is a most pitiful and strange story” (quoted by Adams, 2000). Adelaide’s marriage was not happy. She had an affair with another man, and died after a botched abortion in 1903 (Adams, 2000).

Dowson had converted to Catholicism in 1891. His conversion may have resulted in part from his courtship of Adelaide, in part from his relations with Lionel Johnson, in part from the fact that it was the thing to do. Whatever the cause, he was formally admitted to the Roman Catholic Church (Adams, 2000, pp 58-59). Yeats doubted his conviction: “Dowson adopted a Catholic point of view without, I think, joining that church, an act requiring energy and decision” (1936, p. x). Yet Dowson was sincere in his beliefs, and he found some release of his guilt and despair in the rituals of the church:

Extreme Unction

Upon the eyes, the lips, the feet,

On all the passages of sense,

The atoning oil is spread with sweet

Renewal of lost innocence.

The feet, that lately ran so fast

To meet desire, are soothly sealed;

The eyes that were so often cast

On vanity, are touched and healed.

From troublous sights and sound set free;

In such a twilight hour of breath,

Shall one retrace his life, or see,

Through shadows the true face of death?

Vials of mercy! Sacring oils!

I know not where nor when I come,

Nor through what wanderings and toils.

To crave of you Viaticum.

Yet when the walls of flesh grow weak,

In such an hour, it well may be,

Through mist and darkness, light will break,

And each anointed sense will see.

Viaticum is the set of provisions for a journey. The word is used for the final Eucharist – the communion given to the dying – but it hearkens back to Roman customs. In Marius the Epicurean, Pater (1985) considers the voyage of the soul released from the body in the chapter on the poem Animula vagula (little wandering soul) of Marcus Aurelius. Dowson’s poem also recalls the death of Marius “Gentle fingers had applied to hands and feet, to all those old passage-ways of the senses, through which the world had come and gone for him, now so dim and obstructed, a medicinable oil” (p. 296). Marius had drifted among the many philosophies of Rome, but ultimately died a Christian martyr even though he had not formally converted to the new faith. Dowson had converted; yet yet no priest was present at his death to anoint his body.

Adams, J. (2000). Madder music, stronger wine: The life of Ernest Dowson, poet and decadent. London: I.B. Tauris.

Alford, N. (1994).The Rhymers’ Club: Poets of the tragic generation. New York: St. Marin’s Press.

Baudelaire, C. (1869, translated by Symons, A., 1905). Poems in prose. London: E. Mathews. The original French Le Spleen de Paris was published after Baudelaire’s death.

Benediktson, D. T. (1989). Propertius: Modernist poet of antiquity. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Dowson, E. C. (1896). Verses. London: L. Smithers.

Dowson, E. C. (1905). Poems. With a memoir by Symons, A., four illustrations by Beardsley, A. and a portrait by Rothenstein, W. London: J. Lane.

Eliot, T. S. (1925). Poems 1909-1925. London: Faber & Gwyer.

Highet, G. (1965). Poets in a landscape. New York: Knopf.

Horace (1st century BCE, translated by Shepherd, W. G., with an introduction by Radice, B., 1983). The complete Odes and Epodes: With the Centennial hymn. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin.

Longaker, J. M. (1944). Ernest Dowson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

O’Neill, E. (1955). Long day’s journey into night. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Pater, W., (1873, revised 1893, edited with textual and explanatory notes by Hill, D. L., 1980). The Renaissance: Studies in art and poetry: the 1893 text. Berkeley: University of California Press. The original 1873 version Studies in the History of the Renaissance is available online.

Pater, W. (1885, edited by Levey, M., 1985). Marius the Epicurean. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin Books.

Plarr, V. (1914). Ernest Dowson: 1888-1897, reminiscences, unpublished letters and marginalia. New York: L.J. Gomme

Propertius, (1st Century BCE, translated Shepherd, W. G., with an introduction by Radice, B., 1985).The poems. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin.

Putnam, M. C. J. (1986). Artifices of eternity: Horace’s fourth book of Odes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Yeats, W. B. (1936).The Oxford book of modern verse, 1892-1935. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Yeats, W. B. (1972). Memoirs: Transcribed and edited by Denis Donoghue. London: Macmillan.