Antigone

Sophocles’ play Antigone tells the story of a young woman who defies the laws of the state in order to do what she believes is right. The issues considered in the play remain as important now as they were almost two and a half millennia ago. Should one follow one’s conscience or obey the law? Does justice transcend the law? How does one determine what is right?

In the words of Hegel, Antigone is

one of the most sublime and in every respect most excellent works of art of all time. Everything in this tragedy is logical; the public law of the state is set in conflict over against inner family love and duty to a brother; the woman, Antigone, has the family interest as her ‘pathos’, Creon, the man, has the welfare of the community as his. (Hegel, 1975, p 464).

The word pathos most commonly means the quality of something that evokes pity. However, Hegel uses the word to denote “an inherently justified power over the heart, an essential content of rationality and freedom of will” (p 232). Pathos is the emotional commitment that defines a person – his or her driving passion. Sophocles’ play presents the conflict of these passions.

The Theban Myths

In order to understand Antigone we need to know what has happened before the play begins. Antigone (441 BCE) was the first of what are now known as Sophocles’ three Theban Plays, the others being Oedipus Tyrranus (429 BCE) and Oedipus at Colonus (409 BCE). The plays were not conceived as a trilogy and Antigone was written before the other two. Aeschylus had also written three plays about Thebes but the initial two of these (about Laius the father of Oedipus and his version of Oedipus) have been lost. Only the third remains: Seven Against Thebes (467 BCE), which describes the siege of Thebes by the Argives. Antigone begins just after the events described in this play.

From the extant plays we can piece together the mythic narrative that leads to Antigone. Laius, king of Thebes, married to Jocasta, is told by the Delphic Oracle that he can only keep his city safe if he dies childless. After having drunkenly fathered Oedipus, Laius has his son left on Mount Cithaeron to die. However, the boy is found by a shepherd and ultimately adopted as a son by King Polybus of Corinth.

When he comes of age Oedipus is told by the Oracle that he will murder his father and marry his mother. Oedipus flees Corinth to prevent this from happening. On the way to Thebes at a place where three roads meet, he comes upon another traveler. They argue and fight; Oedipus kills the man; the man was Laius.

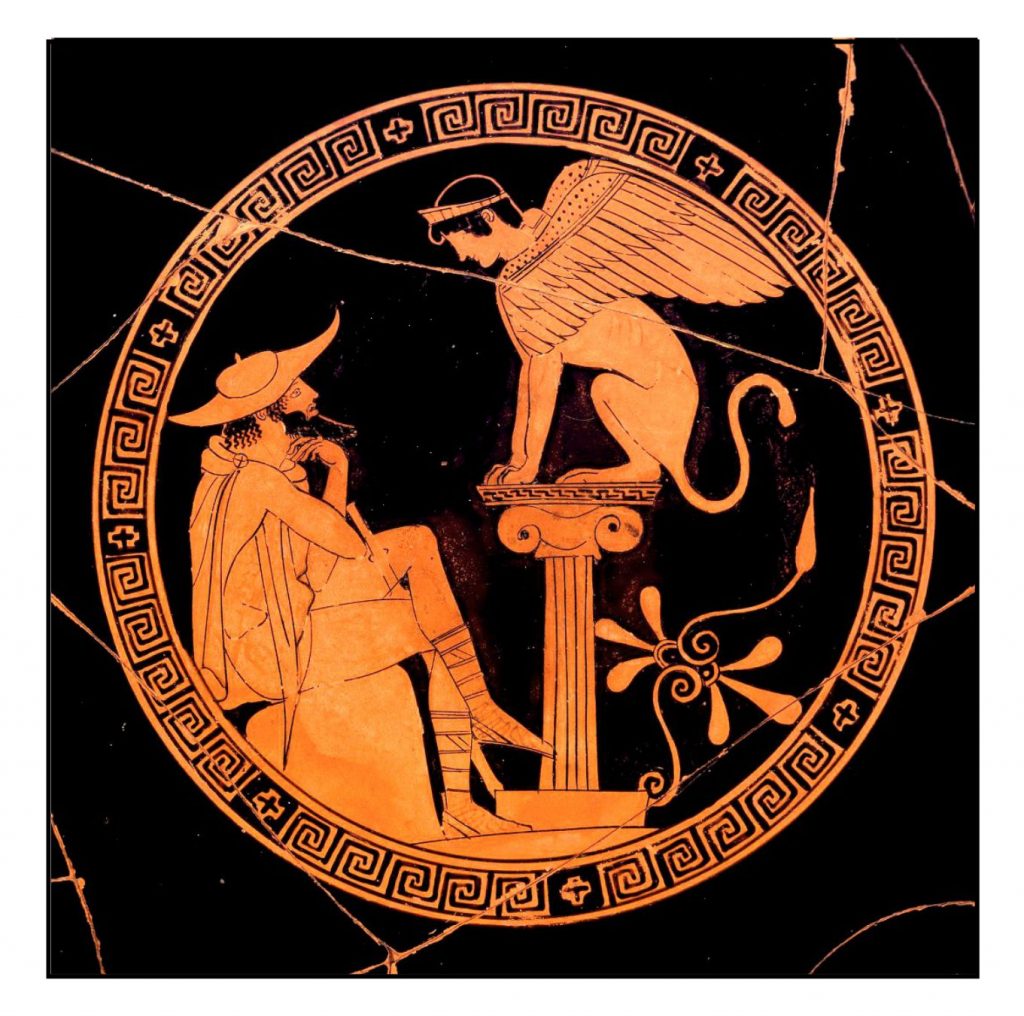

Oedipus continues on to Thebes. The city has long been plagued by the Sphinx, a monster sent by the gods because of some ancient crime of the Thebans. The Sphinx poses a riddle to all who pass by and devours those that fail to answer correctly: “What goes on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night.” The illustration at the right shows a representation of Oedipus and the Sphinx in a vase from around 500 BCE, now in the Vatican. (The sphinx seems much less monstrous than the legend indicated.) Oedipus solves the riddle – “man, who crawls in infancy, walks as an adult and uses a cane in old age.” This releases the city from the monster’s power. In gratitude the citizens of Thebes make Oedipus king and grant him the recently bereaved Jocasta as his wife. Oedipus and Jocasta have four children: the boys Polyneikes and Eteokles, and the girls Antigone and Ismene

Oedipus continues on to Thebes. The city has long been plagued by the Sphinx, a monster sent by the gods because of some ancient crime of the Thebans. The Sphinx poses a riddle to all who pass by and devours those that fail to answer correctly: “What goes on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three at night.” The illustration at the right shows a representation of Oedipus and the Sphinx in a vase from around 500 BCE, now in the Vatican. (The sphinx seems much less monstrous than the legend indicated.) Oedipus solves the riddle – “man, who crawls in infancy, walks as an adult and uses a cane in old age.” This releases the city from the monster’s power. In gratitude the citizens of Thebes make Oedipus king and grant him the recently bereaved Jocasta as his wife. Oedipus and Jocasta have four children: the boys Polyneikes and Eteokles, and the girls Antigone and Ismene

The gods, displeased at the unrevenged death of Laius, bring a plague down upon Thebes. In order to stop the plague Oedipus searches for his father’s murderer. In the course of his investigations he realizes first that he was the killer, and ultimately that Laius was his father and Jocasta his mother. Jocasta hangs herself. Unable to bear the pain of his knowledge Oedipus blinds himself with Jocasta’s brooch pins. Exiled from Thebes he seeks sanctuary in the grove of the Furies at Colonus, a village near Athens. Here Theseus, king of Athens, takes pity on him.

His daughters Ismene and Antigone come to comfort their father in Colonus. In Thebes the sons of Oedipus initially decide to alternate the kingship, but Eteokles then banishes his older brother Polyneikes and becomes sole king of Thebes. Polyneikes visits Oedipus in Colonus to get his blessing for a revolt against his brother, but Oedipus curses both his sons and prophecies that they will die at each other’s hand. Oedipus dies. His daughters return to Thebes.

Polyneikes and six other generals raise an army from the rival state of Argos and attack Thebes. The Thebans ultimately defeat the besieging army. Near the end of the siege, Polyneikes and Eteokles fight and kill each other.

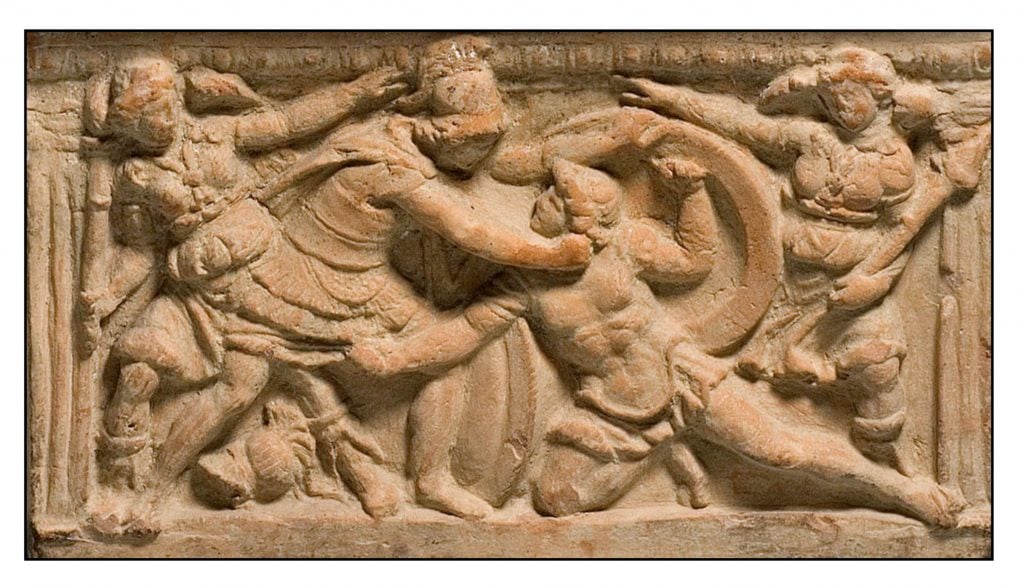

The deaths of Polyneikes and Eteokles became a popular motif for sculpture, the illustration below showing a relief on an Etruscan funerary urn from Chiusi (circe 200 BCE).

The following illustration from a 19th century jewel shows a more restrained view of the brothers’ deaths.

The following illustration from a 19th century jewel shows a more restrained view of the brothers’ deaths.

The Story of Antigone

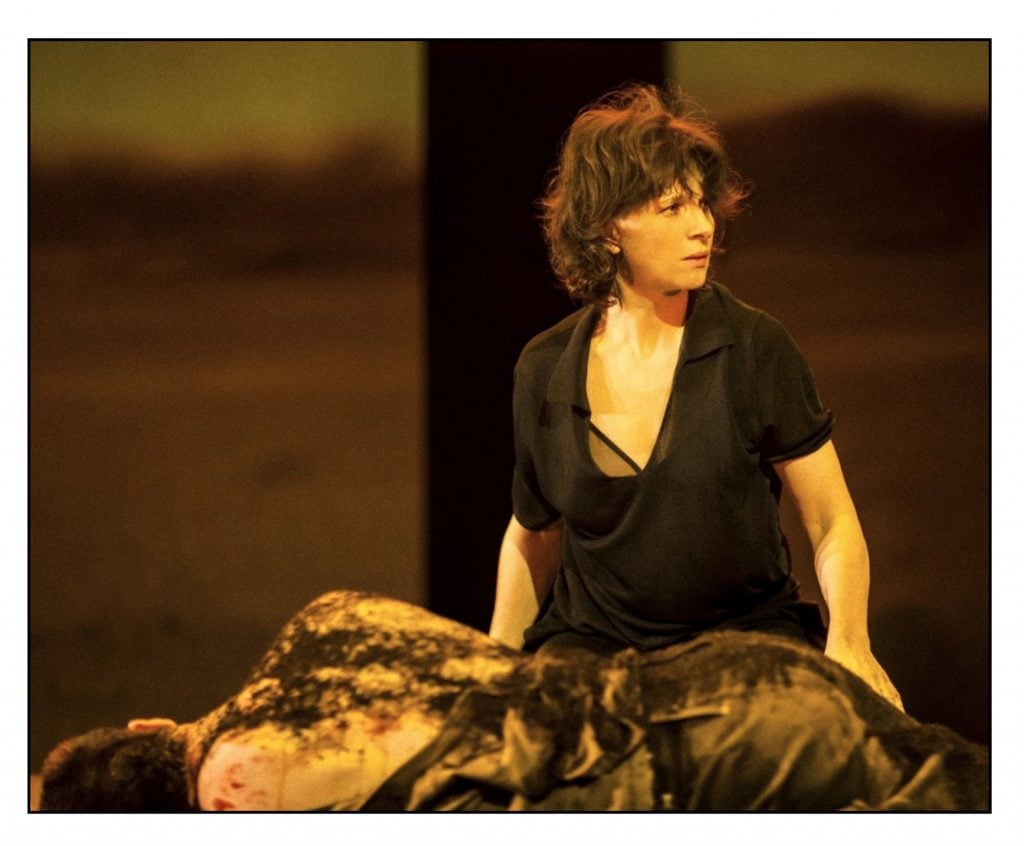

After the deaths of Polyneikes and Eteokles, Kreon, the brother of Jocasta, becomes king of Thebes. He decrees that Eteokles be given a hero’s funeral rites but that the body of the traitor Polyneikes’ be left to rot. Anyone who disobeys this ruling will be put to death. Despite the warnings of her sister, Antigone refuses to obey Kreon’s commandment and casts earth over Polyneikes’ body. The illustration below shows Juliet Binoche in the 2015 production of Antigone at the Barbican in London.

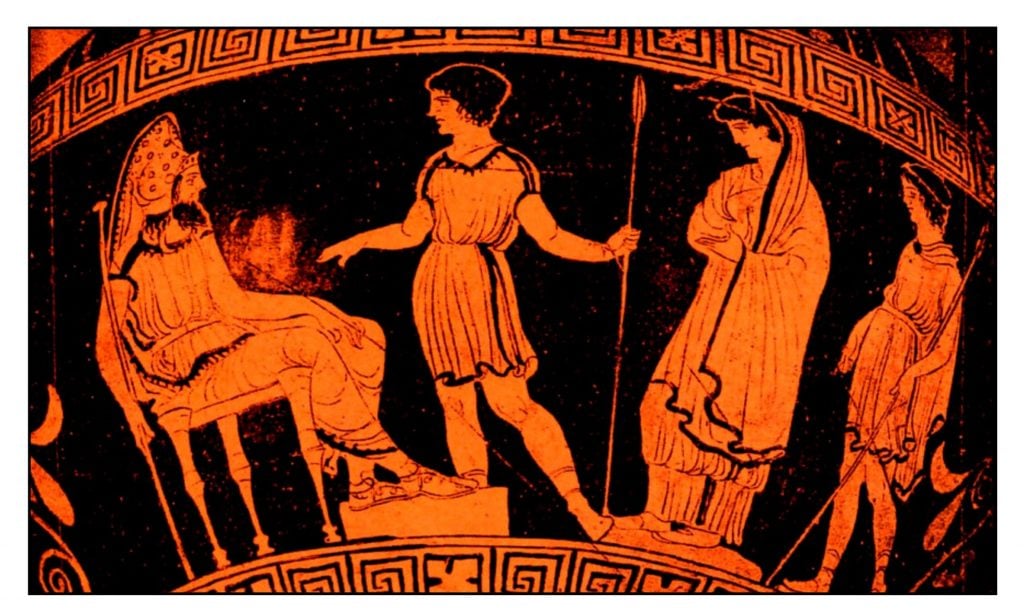

Antigone is caught in the act. The following illustration from a Greek vase (circe 400 BCE) shows Antigone, flanked by two guards holding spears, brought before Kreon.

This is the crucial exchange between the two:

Kreon: Now tell me, not at length, but in brief space,

Knew you the order not to do it?

Antigone: Yes

I knew it; what should hinder? It was plain.

Kreon: And you made free to overstep my law?

Antigone: Because it was not Zeus who ordered it,

Nor Justice, dweller with the Nether Gods,

Gave such a law to men; nor did I deem

Your ordinance of so much binding force,

As that a mortal man could overbear

The unchangeable unwritten code of Heaven;

This is not of today and yesterday,

But lives forever, having origin

Whence no man knows: whose sanctions I were loath

In Heaven’s sight to provoke, fearing the will

Of any man. I knew that I should die –

How otherwise? Even although your voice

Had never so prescribed. And that I die

Before my hour is due, that I count gain.

For one who lives in many ills, as I –

How should he fail to gain by dying? Thus

To me the pain is light, to meet this fate:

But had I borne to leave the body of him

My mother bare unburied, then, indeed,

I might feel pain; but as it is, I cannot:

And if my present actions seems to you

Foolish – ‘tis like I am found guilty of folly

At a fool’s mouth! (ll 446-470, Young translation)

This is one of the greatest speeches ever spoken on the stage. It comes in four parts. First, Antigone scorns the proclamation of Kreon. Made neither by the gods of Olympus nor by the lords of Hades, this was an “order” rather than a “law.” Second, she vaunts the eternal “unwritten code of Heaven” that guides human behavior and that must not be disobeyed. In the third section of the speech, Antigone recognizes that her defiance might bring about her death. However, this will bring relief to one who has already lost father, mother, and two brothers. Finally, she tells Kreon that she is not the one who is acting foolishly. He who does not understand the code of Heaven is far more fool than she. The following film-clip shows Irene Papas as Antigone and Manos Katrakis as Kreon (Tzavellas, 1961):

The chorus is upset by Antigone’s defiance. Kreon refuses to grant Antigone mercy and sentences her to be buried alive in a cave. Kreon’s son, Haimon, in love with Antigone, pleads with his father, but Kreon remains adamant. In his defense, he states the case for the rule of law:

Obedience is due

To the state’s officer in small and great,

Just and unjust commandments; …

There lives no greater fiend than Anarchy;

She ruins states, turns houses out of doors

Breaks up in rout the embattled soldiery;

While Discipline preserves the multitude

Of the ordered host alive. Therefore it is

We must assist the cause of order.

(ll 665-676, Young translation)

Haimon urges his father not to be so stubborn:

it’s no disgrace for a man, even a wise man,

to learn many things and not to be too rigid.

You’ve seen trees by a raging winter torrent,

how many sway with the flood and salvage every twig,

but not the stubborn—they’re ripped out, roots and all.

Bend or break. The same when a man is sailing:

haul your sheets too taut, never give an inch,

you’ll capsize, and go the rest of the voyage

keel up and the rowing-benches under.

(ll 710-717, Fagles translation)

Kreon refuses to listen to his son.

Meanwhile, Antigone bemoans her fate. She accepts that she did what she had to do, but she regrets that she was not able to marry or have children. She does not understand why the gods have not intervened to save one who served them truly. Before she is taken to the cave she asks the Thebans to behold one who has been condemned

τὴν εὐσεβίαν σεβίσασα. (ten eusebian sebisasa) (l 943)

In an act of perfect piety (Carson translation)

For doing reverence where reverence was due. (Brown translation)

The noun eusebia means an act of reverence or piety; the verb sebizo is to worship or honor. Carson (2015, pp 5-6) remarks about this emphatic conclusion:

Both noun (eusebia) and verb (sebizo) derive from the Greek root seb-, which refers to the awe that radiates from gods to humans and is given back as worship. Everything related to this root has fear in it. But eusebia is a fear that moves as devotion – a striving out of this world into another and of another world into this.

Teiresias, the blind seer, tells Kreon that the gods are displeased: they wish Antigone to be freed and Polyneikes properly buried. Kreon orders Antigone’s release but she has already killed herself. In grief at her death, Haimon commits suicide. In grief at the death of her son, Kreon’s wife Eurydike also commits suicide. Utterly broken, Kreon is led away, his life emptied of any meaning. He is “as a dead man who can still draw breath.” (l 1167, Gibbons translation)

The Choral Odes

One of the great attractions of Sophocles’ play is the way in which the chorus of Theban elders comment on the action. The play contains six main choral odes. The first is a celebration of the Theban triumph over the besieging Argives. The most exciting recent translation of this begins

The glories of the world come sharking in all red and gold

we won the war

salvation struts

the streets of sevengated Thebes

(ll 100-102, Carson translation)

The choral odes were sung and danced by a chorus of about fifteen men in the area of the theatre known as the orchestra (“place for dancing”). Carl Orff wrote music for the performance of Antigonae (1949) that suggests how the chorus might have sounded. The following is Orff’s music for the introduction of the Chorus and the beginning of this first ode:

The second ode, often known as the Ode to Man, considers how wonderful is the creature called man, who can navigate the sea, cultivate the land, tame the animals, build homes for protection against the elements, and find medicine for his ailments. The following translation of the beginning of the ode attempts the rhythms of the Greek:

At many things – wonders

Terrors – we feel awe

But at nothing more

Than at man. This

Being sails the gray-

White sea running before

Winter storm-winds, he

Scuds beneath high

Waves surging over him

On each side

And Gaia, the Earth

Forever undestroyed and

Unwearying, highest of

All the gods, he

Wears away, year

After year as his plows

Cross ceaselessly

Back and forth, turning

Her soil with the

Offspring of horses.

(ll 332-345, Gibbons translation)

The following is Carl Orff’s 1949 setting of the opening of the Ode to Man. Orff used the words of Hölderlin: Ungeheuer ist viel. Doch nichts ungeheuerer als der Mensch (Many things are wonderful but nothing more wonderful than man). Orff’s music captures the awe at the beginning of the ode, and then gives a driving rendition of human achievements.

The Greek word used to describe man at the beginning of this famous ode – deinos – usually means “extraordinary” or “wonderful.” It also has connotations of the supernatural or uncanny, the unexpectedly clever, or even the monstrous. The word comes from a Proto-Indo-European root dwei denoting fear. An example of this root in English is “dinosaur.” Deinos has no obvious equivalent in English. The German ungeheuer (enormous, terrible, unnatural) used by Hölderlin captures many of its meanings.

The later choral odes in Antigone tell how human hopes often come to naught, describe the power of human passion, console Antigone as she is led away to her fate, and at the end of the play praise the gods who teach us wisdom. The following are three modern translations of the final words of the chorus:

Wisdom is by far the greatest part of joy,

and reverence toward the gods must be safeguarded.

The mighty words of the proud are paid in full

with mighty blows of fate, and at long last

those blows will teach us wisdom

(ll 1347-1353, Fagles’ translation)

Wise conduct is the key to happiness

Always rule by the gods and reverence them.

Those who overbear will be brought to grief.

Fate will flail them on its winnowing floor

And in due season teach them to be wise.

(Heaney translation)

There is no happiness, but there can be wisdom.

Revere the gods; revere them always.

When men get proud, they hurl hard words, then suffer for it.

Let them grow old and take no harm yet: they still get punished.

It teaches them. It teaches us.

(Paulin translation)

Fagles has the gods teaching all of us, whereas Heaney has them only teaching the proud. Paulin gives both meanings. This section from Orff’s Antigonae is appropriately otherworldly: Um vieles ist das Denken mehr denn Glückseligkeit. (Thought is much greater than happiness).

The following is a clip from the ending to Tzavellas’ 1961 film with Manos Katrakis as Kreon and Thodoris Moudis as the leader of the chorus:

Conflict

The heart of the play is the conflict between Kreon and Antigone. Steiner (1984, pp 231-232) notes that

It has, I believe, been given to only one literary text to express all the principal constants of conflict in the condition of man. These constants are fivefold: the confrontation of men and of women; of age and of youth; of society and of the individual; of the living and the dead; of men and of god(s). The conflicts which come of these five orders of confrontation are not negotiable. Men and women, old and young, the individual and the community or state, the quick and the dead, mortals and immortals, define themselves in the conflictual process of defining each other. Self-definition and the agonistic recognition of ‘otherness’ (of l’autre) across the threatened boundaries of self, are indissociable. The polarities of masculinity and of femininity, of ageing and of youth, of private autonomy and of social collectivity, of existence and mortality, of the human and the divine, can be crystallized only in adversative terms (whatever the many shades of accommodation between them). To arrive at oneself—the primordial journey—is to come up, polemically, against ‘the other’. The boundary-conditions of the human person are those set by gender, by age, by community, by the cut between life and death, and by the potentials of accepted or denied encounter between the existential and the transcendent.

In his assessment of the play, Hegel focused on the conflict between a person’s kinship-duties and the allegiance owed to the state (Reidy, 1995; Young 2013, pp 110-139). In his mind Antigone represented civilization’s necessary change from family-loyalty to state-citizenship. This fits with Hegel’s general view of history as a sequence of dialectic conflicts between different world-views. Progress occurs as the two competing ideas become reconciled. The tragedy occurs because neither Antigone nor Kreon can see the other side of the conflict. Antigone feels no duty to the state; Kreon pays no attention to his family, completely disregarding his son’s concerns.

The balance between Antigone and Kreon is what makes Antigone a tragedy. Albert Camus (1955/1968, p 301) differentiated tragedy from drama:

the forces confronting each other in tragedy are equally legitimate, equally justified. In melodramas or dramas, on the other hand, only one force is legitimate. In other words, tragedy is ambiguous and drama simple-minded. In the former, each force is at the same time both good and bad. In the latter, one is good and the other evil (which is why, in our day and age, propaganda plays are nothing but the resurrection of melodrama). Antigone is right, but Kreon is not wrong.

In the conflict Antigone and Kreon are very similar in character. Steiner (1984, pp 184-5) points out

Both Kreon and Antigone are auto-nomists, human beings who have taken the law into their own keeping. Their respective enunciations of justice are, in the given local case, irreconcilable. But in their obsession with law, they come very close to being mirror-images.

The tragedy evolves because neither Antigone nor Kreon is able to compromise. They are both bloody minded – obstinate to the point of bloodshed. However, Kreon is the more reprehensible: his edict forbidding the burial of Polyneikes is not based on either divine rule or reasoned thought.

Three conflicting forces are at play in Antigone. One is the law (nomos) of the state (polis). The second is the set of “unwritten rules” (agrapta nomima) that tell us what is right. The third is fate (moira) – the working out of what must necessarily happen. Of these only the first is easy to understand.

Natural Law

Antigone’s “unwritten code of Heaven” is often considered the same as the “natural law” – that which we know because it is an essential part of our being (Robinson. 1991; Burns, 2002). Natural law is understood by “conscience” – our intuitive sense of what is right and wrong. Regardless of how we are educated or how our society operates, conscience tends to work similarly: murder and incest are wrong; hospitality and compassion are right. Human history has long realized that the laws promulgated to maintain order in particular societies may come into conflict with an individual’s conscience. In these cases, the natural law should generally be paramount. This is the basis of civil disobedience. An unjust law – one that is out of harmony with the natural law – need not be obeyed:

How does one determine whether a law is just or unjust? A just law is a man made code that squares with the moral law or the law of God. An unjust law is a code that is out of harmony with the moral law. To put it in the terms of St. Thomas Aquinas: An unjust law is a human law that is not rooted in eternal law and natural law. Any law that uplifts human personality is just. Any law that degrades human personality is unjust. (King, 1963).

However, the natural law is often difficult to determine. It is understood by intuition, and followed by inclination (Maritain, 2001, pp 32-38). So when should conscience take precedence over the law? The laws promulgated by a state should be and often are derived from the natural law. However, they sometimes also exist to entrench the status of the powerful.

The laws or commandments proclaimed in religious scriptures are also related to the natural law However, even this relationship is complex. On the one hand, the natural law can be conceived as independent of divinity. Hugo Grotius famously stated that we know what is right “even if we concede … that there is no God” (etiamsi daremus … non esse Deum). Others, such as Maritain (2001, p 46), propose that the natural law as perceived by man derives from the “eternal law” as perceived by God. Human perception of the divine law is as yet imperfect.

The relation between natural law and nature is also complex. Laws of nature (phusis) are deduced from experience of the real world. They portray what is rather than what should be. Such laws can be demonstrated, analyzed and tested. The natural laws for human behavior are understood by intuition. We know what is right but we do not understand how we know. Nor can we demonstrate or test the laws that we follow.

If the natural law is the sum of human dispositions, then we might be able to study it in terms of evolution. Since most of human existence was spent in small bands that hunted and gathered on the African Savannah, many human dispositions to behave in particular ways may have been selected to promote the survival of these small groups. Commandments against murder (other than in self-defense) clearly facilitate group-survival. Edicts against incest decrease the probability of deleterious recessive genes becoming homozygous, and by promoting exogamy (marriage outside of the group) enlarge and strengthen the group.

If natural causes such as evolution are the basis for our morality, perhaps we can determine what is right by what is considered natural. Many people consider homosexuality “unnatural.” In the Abrahamic religions, early laws expressly prohibited homosexual relations on pain of death.

If a man also lie with mankind, as he lieth with a woman, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.” (Leviticus 20:13).

Aquinas argued that homosexuality is unnatural because it does not lead to procreation, which is the natural purpose of sexual intercourse (Summa Theologica II I 94). Yet who or what defines the natural purpose of an act and why should there be only one purpose?

How does Antigone know that she is right to bury her brother, even if her act will entail her death? She is following a “custom” – the Greeks buried their dead. Other cultures cremate their dead, or leave them out to be devoured by carrion-eating birds – “sky burial.” It is difficult to see burying the dead as an absolute requirement of natural law, though some unspecified honoring of the dead seems common to all human cultures.

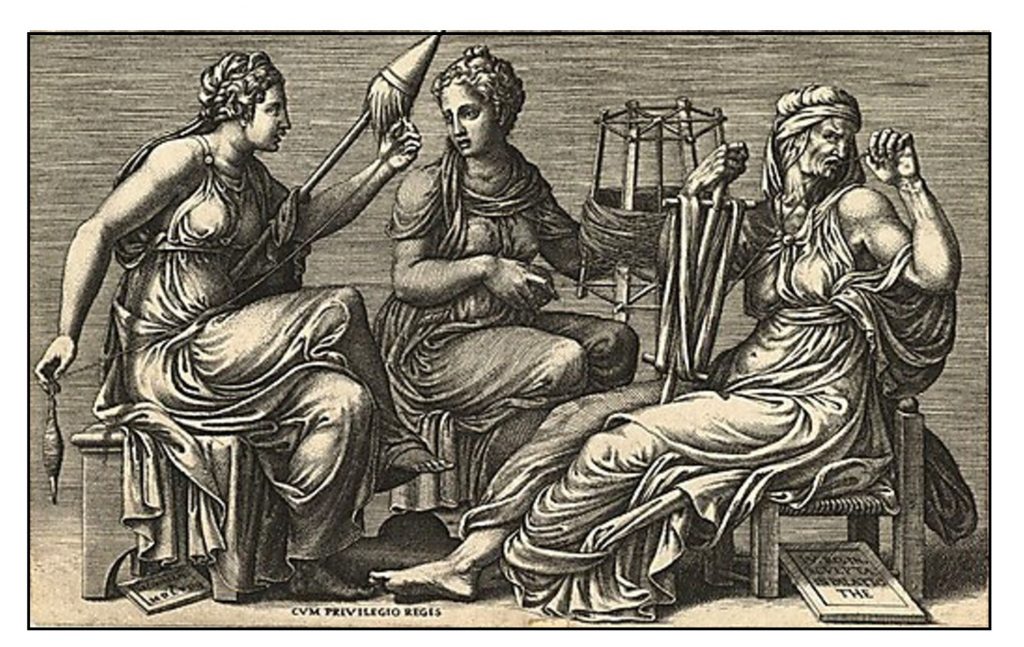

Fate

The Ancient Greeks attributed much that happens in life to fate. Fate was often personified as three women – the moirai. The word derives from meros, a part, share or portion. Clotho spins the thread of a life; Lachesis allots the life to a particular person; and Atropos cuts the thread at death. Neither human nor divine intervention can affect the actions of the fates. The following is a print of The Three Fates (1558) by Giorgio Ghisi.

Although Antigone has obeyed the unwritten code of heaven, the gods cannot intervene to save her from her ignominious death. That has been otherwise ordained – it is her fate. After Antigone is led away, the Chorus remarks that such apparently unjust ends have been suffered by others before her. Fate is a terrible thing:

The power of fate is a wonder,

dark, terrible wonder –

neither wealth nor armies

towered walls nor ships

black hulls lashed by the salt

can save us from that force.

(ll 951-954, Fagles’ translation)

Fate is described as deinos (terrible), the same word that the chorus used to describe man. We are both made and unmade by fate. We should follow the unwritten code of the gods, but doing so will not prevent death. The Fates operate according to some other code. Perhaps they follow necessity rather than justice. Perhaps they follow laws that operate beyond the individual life. The chorus briefly mentions such a possibility: Antigone may be paying for the sins of her father. However, it is possible that the Fates do not follow any code of justice. They may just enforce the physical laws by which the universe operates.

Justice

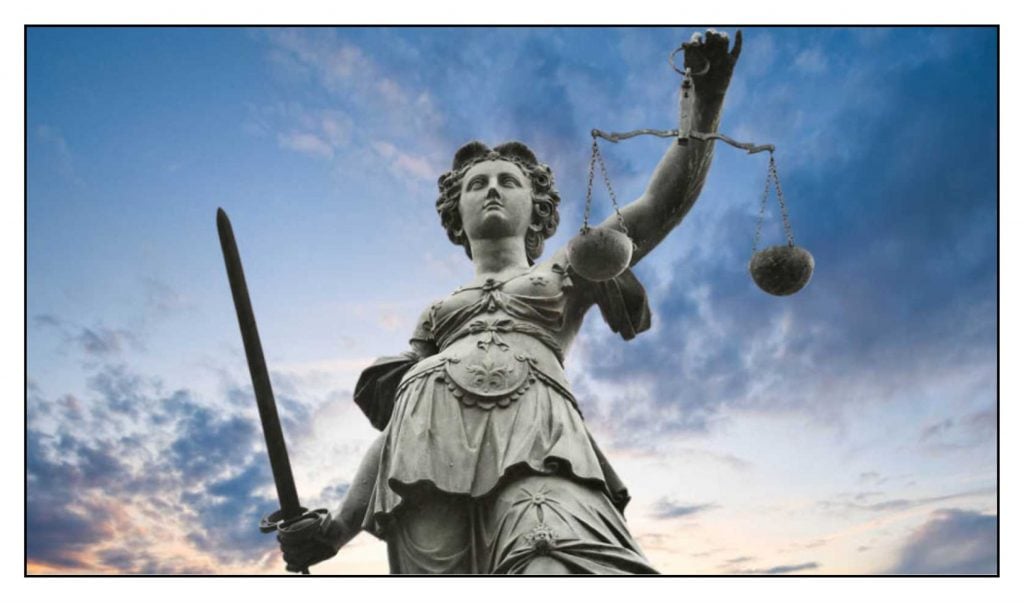

Justice is the human concept of what is right. Our words related to justice – law, morality, fairness, equity, right, righteousness – overlap in their meanings. The Greeks at the time of Sophocles also had many words (Steiner, 1984, pp 248-251; Nonet, 2006). Precise translations distinguishing these one from another are usually not possible, and the usage of the terms changed over the years.

The Greeks often personified their ideas in terms of gods. Themis was a Titaness who personified divine law. Zeus and Themis had three daughters: Dike, law; Eunomia, order; and Eirene, peace. Dike is customarily represented with a sword and a set of scales for weighing right and wrong (as in the illustrated statue from the Frankfurt Fountain of Justice, an 1887 bronze replacement for the original 1611 stone statue). Another Greek word dikaiosune came to mean both a system of justice and the virtue of righteousness (Havelock, 1969). Antigone appeals to Dike as the supporter of the unwritten laws which require the burial of the dead.

The Greeks differentiated nomos – the set of socially constructed laws – from phusis – the laws underlying the universe. The word nomima (laws, regulations, customs) derives from nomos but Antigone used it to distinguish the eternal and unwritten laws from human laws. Words do not clearly show us what is right. And they fail to clearly differentiate laws that are given from those that are constructed. Sophocles’ tragedy deals in part with our inability to know with certainty what is just.

Modern Adaptations

The story of Antigone has been retold many times (Chancellor, 1979: Steiner, 1984). These versions stress different aspects of the story, supplement the main plot with other events, or place the story in a different time and place. For brevity I shall only consider a few recent adaptations.

(i) Anouilh

During the Nazi occupation of France, Jean Anouilh wrote a version of Antigone that was set in modern times. The play was accepted by the censors and produced in Paris in 1944. Anouilh made Kreon a more sympathetic character. He removed from the play the character of Tiresias, who in Sophocles’ original play confirmed that Antigone was right. The chorus was no longer a group of Theban citizens who commented on the actions. Rather the chorus acted as a foil between the audience and the actors, describing what was going to happen and why. In this way Anouilh distanced the audience from becoming directly involved in the tragedy.

Anouilh’s Antigone is more of an existential heroine than a tragic one – she did what she did because she was seeking a reason for her life. As Kreon explains

She wanted to die! None of us was strong enough to persuade her to live. I understand now. She was born to die. She may not have known it herself, but Polynices was only an excuse.

At the end after everyone who had to die has died, Kreon goes on about his work of governing the city. The chorus explains

It’s over. Antigone’s quiet now, cured of a fever whose name we shall never know. Her work is done. A great, sad peace descends on Thebes, and on the empty palace where Creon will begin to wait for death. Only the guard are left. All that has happened is a matter of indifference to them. None of their business. They go on with their game of cards.

Anouilh’s chorus thus appears to attenuate the tragedy. However, Anouilh and his audience most certainly understood the nature of Antigone’s fever as La Résistance.

How could the German occupation authorities have allowed such a production? Steiner (1984, p. 190) notes that the evaluation of Antigone’s story in Germany between the world wars differed from that in other countries. Frightened by the communist revolts that followed the Great War, Germans saw the need for people like Kreon to maintain the safety of the state. So even if they might have felt that Antigone was right, they also knew that Kreon was not wrong. The great German philosopher Hegel had said that the state must necessarily take precedence over family and personal conscience.

(ii) Brecht

Bertolt Brecht wrote and produced a theatrically stunning version of Antigone in Switzerland in 1948. The play was preceded by a prologue set in Berlin in April 1945. This tells the story of how a young deserter from the army came to his sisters’ home bringing food for his hungry family. However, he was captured by the police and hung for treason. His body was left hanging as an example to other would-be deserters. The prologue is doubly distanced from the play. As well as being set in the near present, the prologue is narrated to the audience by one of the sisters but acted out by both. The prologue ends with a police officer asking the sisters whether they knew the traitor. The first denies her brother, but the second goes out to cut down his body.

The play then reverts to Thebes. However, the situation differs from that of Sophocles’ Antigone. Thebes had not been under siege. Rather Kreon had embarked on a war against Argos to gain their iron ore. Eteokles had been brutally killed during this war. Polyneikes saw his older brother being trampled to death, deserted from the futile battle, and was then killed by his own people. The opening choral ode, rather than celebrating the survival of the city, welcomes the wagons of booty and plunder returning from the war.

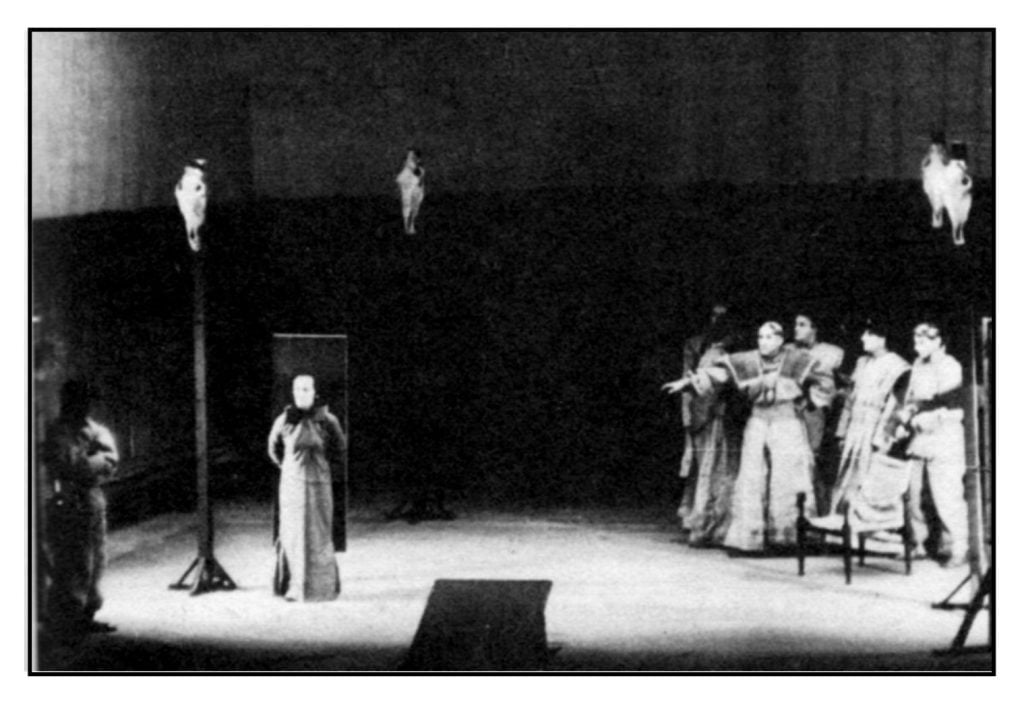

When Antigone is captured and brought before Kreon, she is bound to a board. Effectively she is carrying a door upon her back. A door she cannot open. The illustration (taken from the Suhrkamp edition of Brecht’s play) is from the first production:

Brecht’s Antigone acts politically. She defies Kreon not so much because of any unwritten laws but because she considers him an evil tyrant. She tries unsuccessfully to goad the chorus to join in her defiance. The exchange between Antigone and Kreon is more extended than in Sophocles. After her initial speech of defiance (much the same as in Sophocles), Kreon praises the success of the war, and Antigone continues:

Antigone: The men in power always threaten us with the fall of The State.

It will fall by dissension, devoured by the invaders

and so we give in to you, and give you our power, and bow down;

and because of this weakness, the city falls and is devoured by the invaders.

Kreon: Are you accusing me of throwing the city away to be devoured by the enemy?

Antigone: The city threw herself away by bowing down before you,

because when a man bows down he can’t see what’s coming at him.

The story plays itself out as in the original Greek, but at the end the city falls to its enemies. The tragedy is that of the people who foolishly followed and who keep following a tyrant. The final words of the chorus are those of despair:

For time is short

and the unknown surrounds us; and it isn’t enough

just to live unthinking and happy

and patiently bear oppression

and only learn wisdom in age.

(iii) Fugard

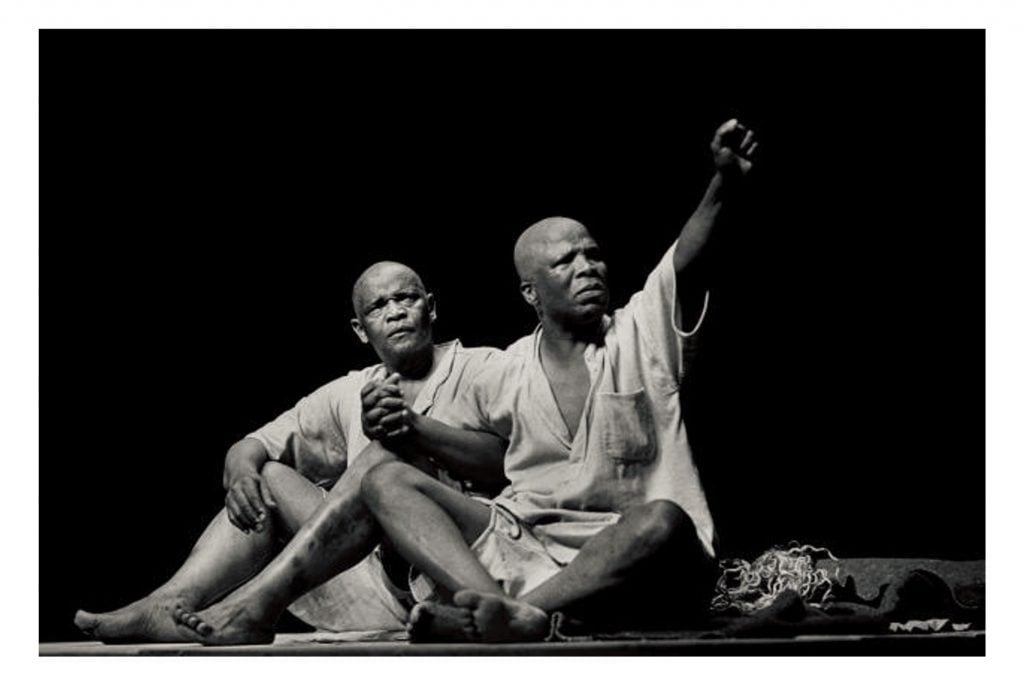

Athol Fugard, John Kani and Winston Ntshona created and produced a play called The Island in South Africa in 1973 as a protest against the persecutions of apartheid. The play is set in an unknown prison camp clearly modelled on Robben Island where Nelson Mandela was held. The play follows two cell mates, played by Kani and Ntshona, in prison for the minor offences of belonging to a banned organization and burning an identity card.

In successive scenes, the two men work at digging holes in the sand and filling them up again, rehearse a performance of Antigone that they plan to present to the camp, learn that one of them may be released but not the other, pretend to talk on the phone with friends and relatives, and finally present the dramatic confrontation between Kreon and Antigone. Below is a photograph showing Ntshona and Kani in the National Theatre revival of the play (2000):

Winston fears that his appearance as a young woman will only cause ridicule, and indeed John bursts into laughter when he first sees him in wig and costume. Yet no one laughs during the final scene when on a makeshift stage Winston tells John

You are only a man Creon. Even as there are laws made by men, so too there are others that come from God. He watches my soul for a transgression even as your spies hide in the bush at night to see who is transgressing your laws. Guilty against God I will not be for any man on this earth.

Nelson Mandela was imprisoned in 1962 for conspiring to overthrow the state. He was not released until 1990.

(iv) Carson

In 2012 Anne Carson wrote Antigonick, a version of Antigone that is more concerned with depicting the ideas and feelings of the play than rendering a literal translation. She added to the play the character of Nick, a surveyor who intermittently and mutely takes measurements of what is happening. Nick stands for the modern viewer who must somehow assess the play coming from a society many hundred years before our own.

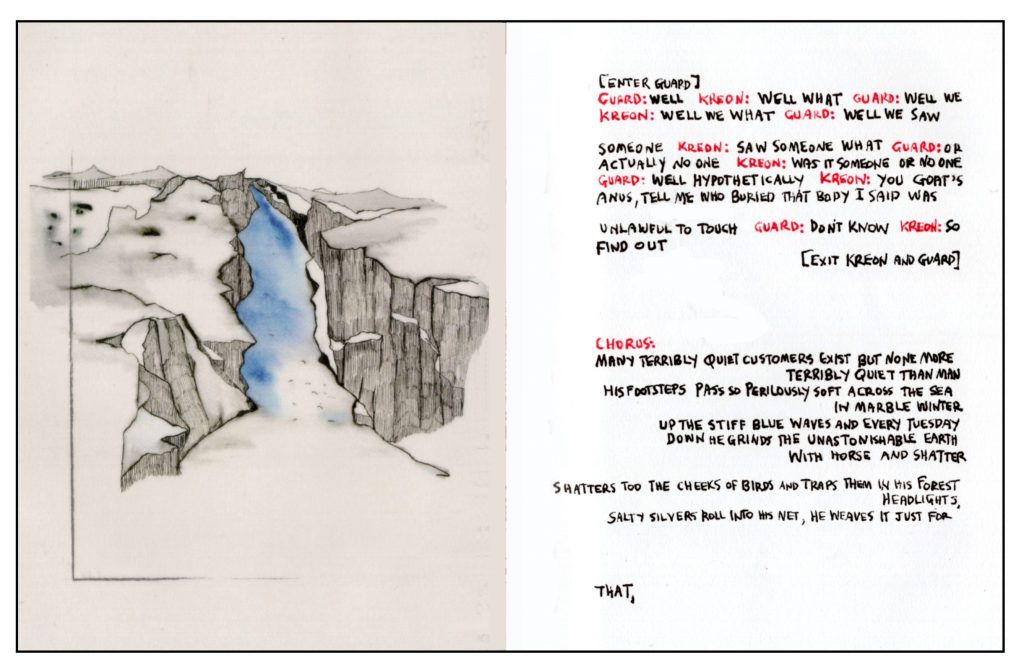

The book is presented with a text that is handwritten by Carson in small black capitals and illustrated with desolate landscapes and surrealistic images by Bianca Stone. These illustrations do not directly relate to the text but add to the book’s sense of incomprehensible passion. Below is a representation the book’s pages at the beginning of the Ode to Man As can be seen in the ode Carson’s choice of words is designed to bring the audience the sense of the original Greek. The word deinos becomes “terribly quiet” – a description that captures the connotations of incomprehensibility and menace.

As can be seen in the ode Carson’s choice of words is designed to bring the audience the sense of the original Greek. The word deinos becomes “terribly quiet” – a description that captures the connotations of incomprehensibility and menace.

Many terribly quiet customers exist but none more

terribly quiet than man

His footsteps pass so perilously soft across the sea

in marble winter

The following illustration shows three other images from the book, one of a wedding cake in desolation, the second of cutlery flying apart under the influence of a thread (perhaps of fate), and the third of a horse upsetting a feast.

In addition, Carson sometimes includes commentary in the text. This brings the meaning up to date. In the original play just before Antigone exits to her death, the chorus provides a long discussion of the way in which fate has acted unfairly, quoting various stories from Greek mythology. A modern audience would not know these examples. In Antigonick Carson therefore replaces this choral ode by verse that slowly goes from mundane commentary to intense grief:

In addition, Carson sometimes includes commentary in the text. This brings the meaning up to date. In the original play just before Antigone exits to her death, the chorus provides a long discussion of the way in which fate has acted unfairly, quoting various stories from Greek mythology. A modern audience would not know these examples. In Antigonick Carson therefore replaces this choral ode by verse that slowly goes from mundane commentary to intense grief:

how is a Greek chorus like a lawyer

they’re both in the business of searching for a precedent

finding an analogy

locating a prior example

so as to be able to say

the terrible thing we’re witnessing now is

not unique you know it happened before

or something much like it

we’re not at a loss how to think about this

we’re not without guidance

there is a pattern

we can find an historically parallel case

and file it away under

Antigone buried alive Friday afternoon

compare case histories 7, 17 and 49

now I could dig up theses case histories,

tell you about Danaos and Lykourgos and the sons of Phineas

people locked up in a room or a cave or their own dark mind

it wouldn’t help you

it didn’t help me

it’s Friday afternoon

there goes Antigone to be buried alive

is there

any way

we can say

this is normal

rational

forgivable

or even in the widest definition just

no not really

(v) Zizek

In 2016 Slavoj Zizek, a provocative philosopher and communist, wrote a version of Antigone that provides three different endings. This idea of multiple endings came from Tom Tykwer’s film Run Lola Run (1998). The plot of Zizek’s Antigone proceeds as in Sophocles until Kreon sentences Antigone to death and is told by Tiresias that he has offended the gods. The first ending then follows as in Sophocles and results in the death of Antigone.

In the second ending the people of Thebes enflamed by the way Kreon offended the gods, rise up and murder him. They set fire to the city. Antigone survives though she is half-mad and does not understand why her simple act of defiance has led to such devastation. The chorus tells her that divine laws are not the ultimate authority:

A society is kept together by the bond of Word,

but the domain of logos, of what can be said,

and this mysterious vortex is what all our endeavours

and struggles are about. Our true fidelity

is to what cannot be said, and the greatest wisdom

is to know when this very fidelity

compels us to break our word, even if this word

is the highest immemorial law. This is where

you went wrong, Antigone. In sacrificing everything

for your law, you lost this law itself.

In the third ending Kreon and Antigone are reconciled, but the citizens of Thebes rise up against their rulers. Kreon is brutally executed because

Much greater evil than a lack of leadership

is an unjust leader who creates chaos in his city

by the very false order he tries to impose. Such an order

is the obscene travesty of the worst anarchy.

The people feel this and resist the leader. A true order,

on the contrary, creates the space of freedom

for all citizens. A really good master

doesn’t just limit the freedom of his subjects,

he gives freedom.

Antigone claims to be on the side of the revolution. But the leader of the people has her executed:

But the excluded

don’t need sympathy and compassion from the privileged,

they don’t want others to speak for them,

they themselves should speak and articulate their plight.

So in speaking for them, you betrayed them even more

than your uncle — you deprived them of their voice.

There is no catharsis. The revolution is brutal. The chorus attempts to excuse the horror by repeating the Ode to Man

There are many strange and wonderful things

but nothing more strangely wonderful than man

But one is left with the nightmare of revolutionaries settling scores by murder. One longs for the simplicity of Sophocles’s original wherein Kreon and Antigone were both striving to do what they thought was right. In Ziztek no one is right. Violence is the only outcome. Justice is not possible. This is not my idea of Antigone. Zizek has not found a way out of the conflict at the basis of the story. Nor has he, a committed communist, portrayed the necessity of revolution as in any way attractive.

Novels

Natalie Haynes has retold the stories of Oedipus and Antigone from the point of view of Jocasta and of Ismene in her novel The Children of Jocasta (2017). In Sophocles’ play Ismene, Antigone’s younger sister, is the only member of Oedipus’ family to survive. She initially serves as a foil for her sister, proposing compromise instead of defiance. Later she stands by her sister, though Antigone refuses her support. In Haynes’ novel the plot has changed from that of Sophocles’ plays, but the story still has its necessary confrontations and reconciliations. The plague plays the role of the Fates.

In Home Fire (2018) Kamila Shamsie has reinterpreted the story of Antigone in terms of Aneeka a young Englishwoman of Pakistani background. Her brother Parvaiz is recruited to ISIS and serves with the terrorists in Syria. Parvaiz is assassinated in Turkey when he tries to leave ISIS. The English government refuses to allow his corpse to be returned to England for burial, and arranges for it to be sent to Pakistan. Aneeka goes to Pakistan to protest this ruling but ultimately the body, the sister and her fiancé are blown to pieces in a suicide bombing.

The situation envisioned by Shamsie is clearly very possible. A citizen should have the right to be buried in his homeland. This right was recently tested in the case of Tamerlan Tsarnaev, one of the bombers at the Boston Marathon (Mendelsohn, 2013). No funeral director or cemetery in Massachusetts would accept his body. After much dispute, a Christian woman in Virginia intervened, and the body was finally buried in an unmarked grave in a small Muslim cemetery in Virginia.

Novels are discursive. They provide us with a wealth of detail, in terms of both things and thoughts. They can discuss what might have been as well as what was. They lack the harsh simplicity of a play.

A Play for All Time

Sophocles’ Antigone remains as a stirring invocation to do what is right. The world needs its Antigones. This was particularly evident in the days of Hitler (von Klemperer, 1992). Those who resisted Nazism did not succeed in changing their government. Yet they did show their countrymen that there were other ways to live and die than slavishly to follow a leader more concerned with power than with humanity.

Sophocles’ play returns time and time again. Whenever governments repress the conscience of their people. World War II generated the Antigones of Anouilh, Brecht and Orff. The situation in South Africa brought about Fugard’s The Island. The situation in Northern Ireland led to Paulin’s The Riot Act. Judith Malina translated Brecht’s Antigone while in jail in 1963 because her Living Theatre had run afoul of the US government.

The philosophy of Sophocles combines a respect for human morality and responsibility with an acquiescence to fate (Kitto, 1961, pp 123-127). In this recognition of the role played by fate, Sophocles differs from his predecessor Aeschylus:

The Aeschylean universe is one of august moral laws, infringement of which brings certain doom; the Sophoclean is one in which wrongdoing does indeed work out its own punishment, but disaster comes, too, without justification; at the most with ‘contributory negligence.’ (p 126)

Wonderful though man is he cannot control everything. This is most obvious in the fact of death. Yet before we die we can do what we believe to be right. This will not prevent our death but it will pay reverence to whatever ideas of transcendence we have conceived, be it the gods or the good.

We do not understand fate. I have already quoted the final words of Sophocles’ chorus – their praise of wisdom. Just before this they make two comments about fate. In reply to Kreon’s desire to die the chorus states

That’s in the future. We must do what lies before us.

Those who take care of these things will take their care.

And then when Kreon says that he prayed for what he longed for, they answer

Don’t pray for anything – for from whatever good

Or ill is destined for mortals, there’s no deliverance.

(Gibbons translation, ll 1334-5, 1337-8)

Sophocles is clear. Do what you think is right. Be open to the ideas of others. Do not expect reward. You will die. Life will carry on.

Texts

Note: the lines for the quotations in this posting are those in the original Greek (Brown edition) and may not fit the lines of the translations.

The Perseus Library Antigone has the full Greek text with translation and commentary by Richard Jebb (from the early 20th century).

Brown, A. (1987). Sophocles: Antigone. Warminster, Wiltshire, England: Aris & Phillips (Greek text and English translation on facing pages; good commentary)

Griffith, M. (1999). Sophocles: Antigone. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (Greek texts, extensive notes and commentary, but no English translation).

Performances

Orff, C., Hölderlin, F., (1949, CD conducted by Sawallisch, W., 1958, CD 2009). Antigonae. Neuhausen: Profil.

Tzavellas, G. [dir.] (film 1961, DVD 2004). Antigone. Kino International Corporation.

Translations

Carson, A., (2015). Sophokles Antigone, London: Oberon Books. This was performed at the Barbican with Juliet Binoche. It is a subdued version of Carson’s Antigonick.

Fagles, R., & Knox, B. M. G. W. (1982). The three Theban plays. London: Allen Lane/Penguin (a fine modern translation)

Gibbons, R., & Segal, C. (2003). Sophocles: Antigone. New York: Oxford University Press (a translation paying close attention to Greek poetic forms)

Heaney, S. (2004). The burial at Thebes: Sophocles’ Antigone. London: Faber and Faber. (perhaps the most beautiful of the translations)

Hölderlin, F. (1804) Sophokles Antigone. (This served as the basis for Carl Orff’s Antigonae). A translation of Hölderlin’s Antigone is available by David Constantine (BloodAxe Books, 2001). The German original is available

Paulin, T., (1985). The riot act: A version of Sophocles’ Antigone. London: Faber and Faber. (translation in modern colloquial English).

Young, G. (1906/1912). The dramas of Sophocles rendered in English verse, dramatic & lyric. Toronto: J.M. Dent & Sons. (the classical blank-verse translation). Available at archive.org

Adaptations

Anouilh, J. (1946/2005). Antigone. Paris: La Table ronde. (English translation by B. Bray & T. Freeman, Bloomsbury Methuen, 2000).

Brecht, B. (1948, edited by Werner Hecht, 1988). Brechts Antigone des Sophokles. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp. (English translation by Malina, J., 1990, Sophocles’ Antigone. New York: Applause Theatre Books).

Carson, A., (2012). Antigonick. (illustrated by Stone, B.). New York: New Directions. Carson and her colleagues presented a reading of Antigonick in 2012 at the Louisiana gallery in Denmark. The Chorus was read by Carson, Antigone by Mara Lee and Kreon by Nielsen.

Fugard, A., Kani, J., & Ntshona, W. (1974). Statements: Sizwe Bansi is dead. The island. Statements after an arrest under the Immorality Act. London: Oxford University Press.

Haynes, N. (2017). The children of Jocasta. London: Mantle Books.

Shamsie, K. (2017). Home fire. New York: Riverhead Books (Penguin)

Žižek, S. (2016). Antigone. London: Bloomsbury Academic

References

Burns, T. (2002). Sophocles’ Antigone and the history of the concept of natural law. Political Studies, 50, 545-557.

Camus, A., (1955, translated by Kennedy, E. C. 1968). On the future of tragedy. In Thody, P. (Ed.) Lyrical and critical essays. (pp. 295-310). New York: Knopf

Chancellor, G. (1979). Hölderlin, Brecht, Anouilh: Three Versions of Antigone Orbis Litterarum, 34, 87-97

Grotius , H. (1625) De jure belli ac pacis (On the Law of War and Peace). Paris: Nicolaus Buon. (Preliminary Discourse XI) English translation available

Hegel, G. W. F. (1835, translated Knox, T. M., 1975) Hegel’s aesthetics: Lectures on fine art. Volume I. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Available

King, M. L. Jr. (1963). Letter from a Birmingham jail. Available

Kitto, H. D. F. (1939/1961/2011). Greek tragedy: A literary study. London: Routledge.

von Klemperer, K. (1992). “What is the law that lies behind these words?” Antigone’s question and the German resistance against Hitler. Journal of Modern History 64, Suppi. (December 1992): S102-S111.

Maritain, J., (edited by Sweet, W., 2001). Natural law: Reflections on theory and practice. South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press.

Mendelsohn, D. (2013) Unburied: Tamerlan Tsarnaev and the lessons of Greek Tragedy. New Yorker (May 14, 2013)

Nonet, P. (2006). Antigone’s Law. Law, Culture and the Humanities, 2, 314-335.

Reidy, D. A. (1995). Antigone, Hegel and the law: an essay. Legal Studies Forum, 19, 239-261.

Robinson, D. N. (1991). Antigone’s defense: a critical study of “Natural law theory: contemporary essays.” Review of Metaphysics, 45, 363-392.

Steiner, G. (1984). Antigones. New York: Oxford University Press.

Young, J. (2013). The philosophy of tragedy: from Plato to Žižek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.