Late Spring

This year winter has stayed longer than usual. The seas are warmer, the Arctic vortex has shifted, and the currents of cold air have veered southward. Yet spring has finally arrived. The snow recedes. Gray and granular patches still remain, but they are not for long. Uncovered, the grass slowly turns from brown to green. Some of the trees, willows in particular, have gained a light green mistiness. Promise of leaves. The creeks are awash with runoff water. Wild waves now ride where once was stillness, ice and rocks. Red-winged blackbirds have returned to join the stay-at-home robins. Occasional cardinals flaunt their crimson. Mallards and geese find stretches of open water in the ice. A peregrine falcon circles slowly. Scattered snowdrops break the ground. Intermittent crocuses begin to show in pale purple and white, and an isolated daffodil braves the cold. The stores are full of cut flowers from countries where spring comes early or from greenhouses where summer is eternal.

The Roman poet Horace (65-8 BCE) described what will happen now in the seventh poem of his fourth book of Odes (Putnam, 1986; Quinn, 1969).

Diffugere nives, redeunt iam gramina campis

arboribusque comae,

mutat terra vices et decrescentia ripas

flumina praetereunt,

Gratia cum Nymphis geminisque sororibus audet

ducere nuda choros

Inmortalia ne speres, monet annus et almum

quae rapit hora diem

The full Latin text and vocabulary are available at the Cambridge Latin Anthology website.

A. E. Housman (1859-1936), author of A Shropshire Lad (1896) and renowned professor of Latin (1892-1936) considered this poem “the most beautiful poem in ancient literature” (Housman/Burnett, 2002, p. 427). He translated the opening lines

The snows are fled away, leaves on the shaws

And grasses in the mead renew their birth,

The river to the river-bed withdraws,

And altered is the fashion of the earth.

The Nymphs and Graces three put off their fear

And unapparelled in the woodland play.

The swift hour and the brief prime of the year

Say to the soul, Thou wast not born for aye.

Housman’s complete translation is available at Poetry X

The prominent rhymes and the archaic words fall uneasily on the modern ear, but fit the style of late Victorian poetry. Free verse might better suit the season that liberates the world from winter.

Scattering the snow, grass returns to the fields

and foliage to the trees.

Earth changes seasons, and the rivers subside

to flow within their banks.

Grace, with her twin-sister nymphs, dares

to lead the naked dancing.

Hope not for immortality, warns the year

whose passing takes away our days.

Rosanna Warren provides a translation (McClatchy, 2002) that quietly plays on the Latin connotations

All gone, the snow: grass throngs back to the fields,

the trees grow out new hair;

earth follows her changes, and subsiding streams

jostle within their banks.

The three graces and the greenwood nymphs,

naked, dare to dance.

You won’t live always, warn the year and the hour

seizing the honeyed day.

Images of the dancing Graces were popular in Roman Italy. The picture on the right shows a fresco from Pompeii, now in the Naples Museum of Archeology. As fluidly as the dance changes meter, the mood of the poem changes. The end of winter highlights the passage of time. And time leads us toward our death. Inmortalia ne speres; hope not for immortality. We shall die just as all have come before, be they kings or poets, good or bad, rich or poor.

Images of the dancing Graces were popular in Roman Italy. The picture on the right shows a fresco from Pompeii, now in the Naples Museum of Archeology. As fluidly as the dance changes meter, the mood of the poem changes. The end of winter highlights the passage of time. And time leads us toward our death. Inmortalia ne speres; hope not for immortality. We shall die just as all have come before, be they kings or poets, good or bad, rich or poor.

Horace then poses to his friend Torquatus the essential question and its obvious answer:

Quis scit an adiciant hodiernae crastina summae

tempora di superi?

Cuncta manus avidas fugient heredis, amico

quae dederis animo

Who knows whether the gods will add tomorrow

to the sum of our todays?

Everything that you can give now to your beloved soul

will escape your heir’s greedy clutches.

These ideas run through all of Horace, and indeed through much of Latin poetry: the transience of life, and the need to live it to its fullest.

From Ode I:4

Vitae summa brevis spem nos vetat incohare longam

Life’s short span forbids us to entertain long-term hopes.

From Ode I:11

Carpe diem, quam minimum credula postero

Seize the day, and trust as little as possible in the future.

From Ode II:4, addressed to Postumus

Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume

labuntur anni.

Alas, Postumus, the fleeting years slip by!

The most striking translation of these last lines is by R. H. Barham, an English cleric of the early 19th century writing under the name of Thomas Ingoldsby.

Years glide away and are lost to me, lost to me!

A marginal note for Ode IV:7 in Rudyard Kipling’s personal edition of Horace (Carrington, 1978) reads:

If all that ever Man had sung

In the audacious Latin Tongue

Had been lost – and This remained

All, through this might be regained.

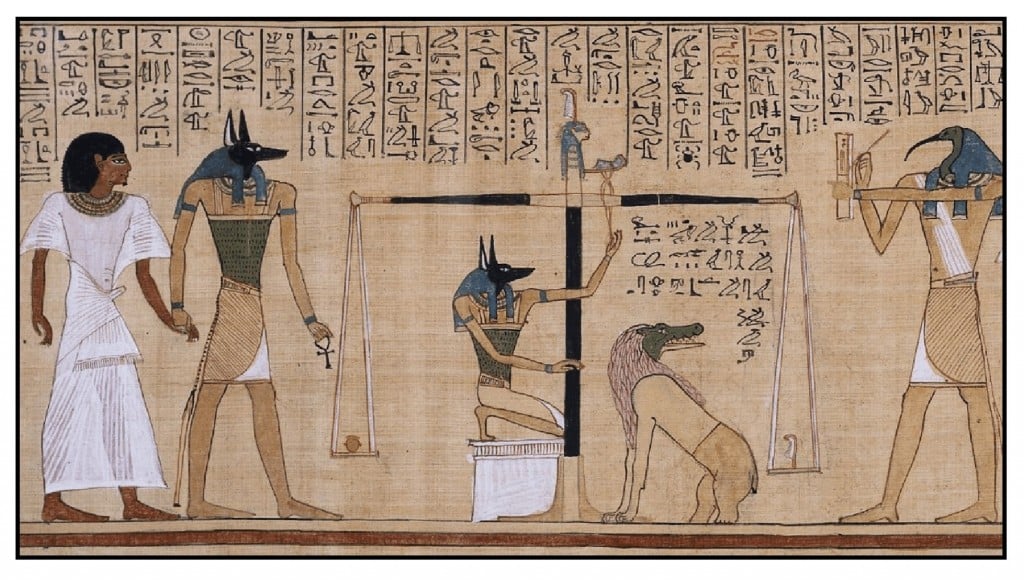

Horace’s suggestion that his fried Torquatus should forget about the future and focus on today is hammered home by reference to the judgment that follows after death.

When thou descendest once the shades among,

The stern assize and equal judgment o’er,

Not thy long lineage nor thy golden tongue,

No, nor thy righteousness, shall friend thee more.

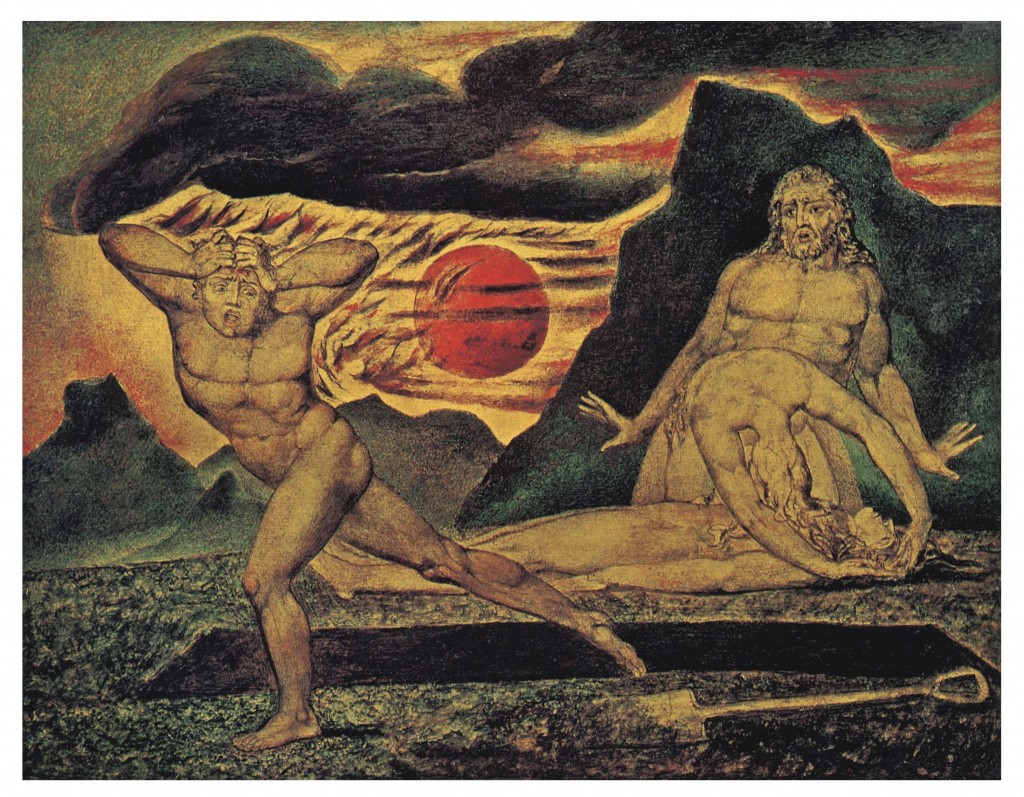

Though not specifically translated by Housman, the Latin poem refers to Minos, the mythical king of Knossos in Crete, who arranged the sacrifice to the Minotaur. In some Roman versions of the afterlife, Minos became on his death the judge for all who die, deciding where in Hades each soul shall reside. Dante’s Inferno placed Minos at the entrance to the second circle of the Inferno. In 1827 William Blake conceived him thus:

Dante and Vergil are on the left. Beyond Minos is the second circle of hell where the sinners who succumbed to lust are whirled around forever in the winds of passion. Among them are Paolo and Francesca of Rimini, who will recount to Dante the sad tale of their forbidden love.

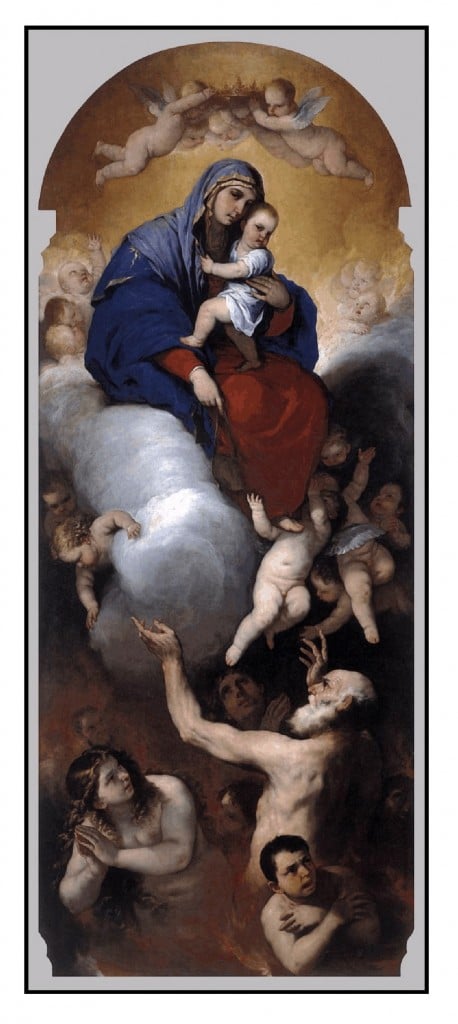

Diffugere nives concludes with the statement that no mortal ever escapes from the underworld. Even the Goddess Diana could not release Hippolytus from Hades. Nor could Hercules free Pirithous. This latter story had special meaning for Alfred Edward Housman.

At university, Housman had fallen utterly in love with Moses Jackson, a fellow student at St John’s College, Oxford. In many ways Jackson was the opposite of Housman: scientist rather than classicist, athlete rather than aesthete, heterosexual rather than homosexual. On their final exams at Oxford in 1881, Jackson obtained a first in science whereas Housman failed. Housman was perhaps troubled by his youthful passions. Yet he also considered much of the curriculum irrelevant to his interests. He simply did not care about the philosophy he was supposed to have studied. After subsequent cramming, Housman finally obtained a Pass degree, and took a lowly clerical position in the Patent Office in London.

Working independently of any institution, Housman quickly became the most accomplished Latin scholar of his generation, publishing brilliant papers on the poems of Propertius and other Roman authors. On the basis of these contributions he was appointed as Professor of Latin at University College in London in 1892. He became Professor of Latin at Trinity College in Cambridge in 1911.

Housman published a book of poems A Shropshire Lad in 1896. The book was brought out at his own expense and did not sell very well at first. However, during the Boer Wars and the Great War, the songs of lost innocence, simple patriotism, unrequited love and early death came to represent the age.

Despite an early quarrel soon after graduation, Jackson continued his friendship with Housman, Yet it was a completely unequal relationship, Housman remaining passionately in love with his heterosexual friend. Jackson moved to India 1887 married in 1889, and then moved to Canada in 1911. Housman and Jackson maintained an active correspondence until Jackson’s death from cancer in 1923. Housman published his second book of verse Late Poems (1922) in order that his friend might see his writings before his death.

For Housman, Moses Jackson was like the great Theseus, the brave and beautiful son of the god Poseidon, and the hero who slew the minotaur. Housman was like Pirithous, the king of the Lapiths, who became fast friends with Theseus. Late in their life, the pair embarked on a foolhardy venture to steal Persephone from Hades. They were both arrested and fastened by chains to the Seat of Forgetfulness. When Heracles later came to Hades to capture the three-headed dog Cerberus, he was able to release Theseus from his bondage, but he could not dislodge Pirithous. Persephone returns annually from Hades in the spring, but Pirithous remains forever frozen.

In a way, Housman’s life remained forever fixed in his unclaimed and unrequited love for Jackson (Graves, 1979: Stoppard, 2006). Tom Stoppard’s play The Invention of Love (1997) considers the anguish of this life. After Jackson left for India, Housman devoted himself to dry textual scholarship. He wrote about Juvenal and Lucan, and wittily criticized the writings of others. The 1926 portrait of Housman by Francis Dodd shows a restrained professor with an acerbic eyebrow.

One of Housman’s major works was a five-volume critical edition of the Astronomicon of Manilius, a relatively unknown Roman author. This is a work of poetic astrology, with no relevance to science, and little meaning aspoetry. The first volume came out in 1903 and the fifth in 1933. The first contains a Latin dedication to “my comrade Jackson, who pays no heed to these writings.” The final lines of the poem (in a recent translation by A. E. Stallings, 2012) read

I send these lines to you who went

Where stars rise in the Orient,

From here where constellations sink

Below the ocean’s western brink.

Take them: for that day will come

To add us to the canceled sum

And give our bones to earth to rot

(For we have no immortal lot,

And souls that will not last forever)

And the chain of comrades sever.

The “canceled sum” recall’s Horace’s “sum of our todays.” The “chain of comrades” recalls the chains that bound Pirithous to the Seat of Forgetfulness.

In the poems that were collected by his brother and published after his death in More Poems, Housman wrote:

Shake hands, we shall never be friends; give over:

I only vex you the more I try.

All’s wrong that ever I’ve done or said,

And nought to help it in this dull head:

Shake hands, goodnight, goodbye.

But if you come to a road where danger

Or guilt or anguish or shame’s to share,

Be good to the lad that loves you true

And the soul that was born to die for you,

And whistle and I’ll be there.

The poem, which dates back to 1893 (Housman/Burnett, 1997, p 445), concerns a quarrel which led to Housman and Jackson becoming temporarily estranged. The exact nature of the quarrel is unknown but probably concerned their out-of-balance relationship.

Our human lot is to die. Before we die we can fall in love. Often this provides happiness. The year moves from winter into spring. Sometimes love triggers anguish. Even the happiest of loves comes to an end. Winter inevitably returns.

Carrington, C. (1978). Kipling’s Horace: Carminibus nonnullis Q. Horatii Flacci nonnulla adiunximus quae ad illius exemplar poeta nostras Rudyard Kipling anglice vel convertit vel imitatus est. London: Methuen.

Graves, R. (1955). The Greek myths. London: Penguin Books. (Chapter 103. Theseus in Tartarus)

Graves, R. P. (1979). A.E. Housman: The scholar-poet. London: Routledge & Paul.

Barham, R. H. (1847) The Ingoldsby legends, or mirth and marvels. Volume 3. (p. 361)

Housman, A. E. (1896). A Shropshire Lad. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Housman, A. E. (edited by Burnett, A., 1997). The poems of A.E. Housman. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McClatchy, J. D. (2002). Horace, the Odes. New translations by contemporary poets. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, M. C. J. (1986). Artifices of eternity: Horace’s fourth book of Odes. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Quinn, K. (1969). Latin explorations: Critical studies in Roman literature. London: Routledge and K. Paul. (Chapter 1. Horace’s Spring Odes).

Stallings, A. E. (2012) To my Comrade, Moses J. Jackson, Scoffer at this Scholarship. Poetry, 99, 524-527.

Stoppard, T. (1997). The invention of love. London: Faber and Faber.

Stoppard, T. (2006). The lad that loves you true. Guardian (June 3).