Intimations of Mortality

We have been here before. The coronavirus pandemic has many precedents. Over the centuries various plagues have swept over our world. Many millions of people have died before their time. From 1347 to 1351 the Black Death killed about 30 million people in Medieval Europe: over a third of the population. From 1918 to 1920 the Great Influenza killed about 50 million people: about 2.5% of the world’s population. Each of these pandemics was as deadly as World War I (about 20 million) or World War II (about 70 million). Pandemics are more worrisome than wars: we cannot sue for peace with a virus. Most of us survived even the worst of past infections. Our systems of immunity will likely once again become victorious in this present pandemic. But just like after a war, we shall be severely chastened. How close we will have come to death will change the way we think. Everything will be seen through the mirror of our own mortality and the transience of our species. The nearness of an ending will distort our thinking. We shall have strange dreams and frightening visions.

John of Patmos

Such dreams and visions came to a man named John almost two millennia ago. In the second half of the 1st Century CE, during the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian, the Christians of the Roman Empire were severely persecuted, the Second Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed, and the Roman Empire was shaken by attacks from without and rebellions from within. There was no pandemic but life was just as uncertain.

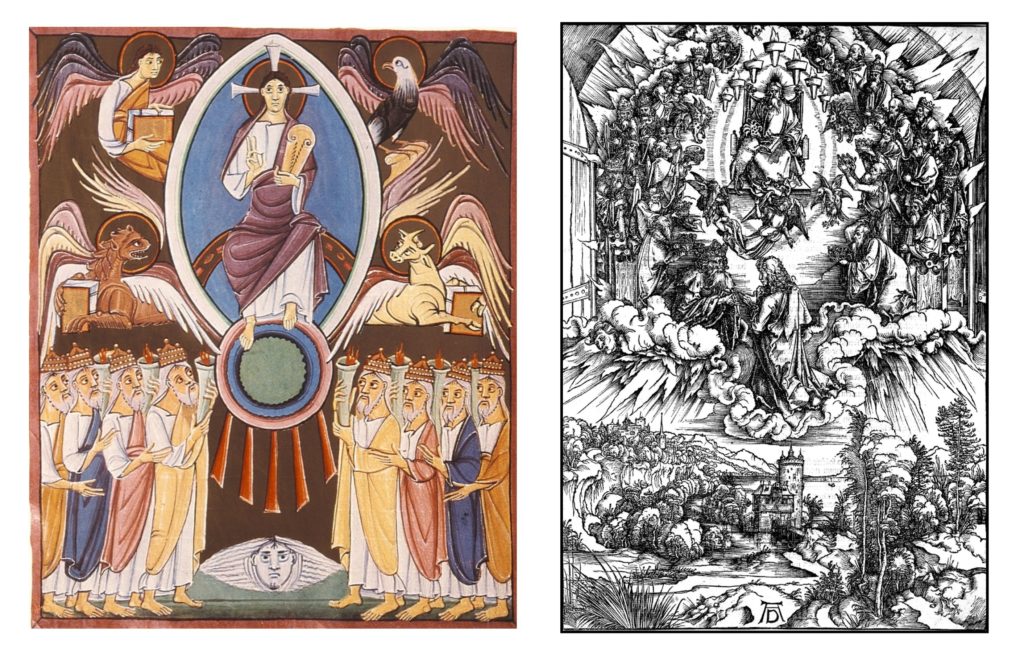

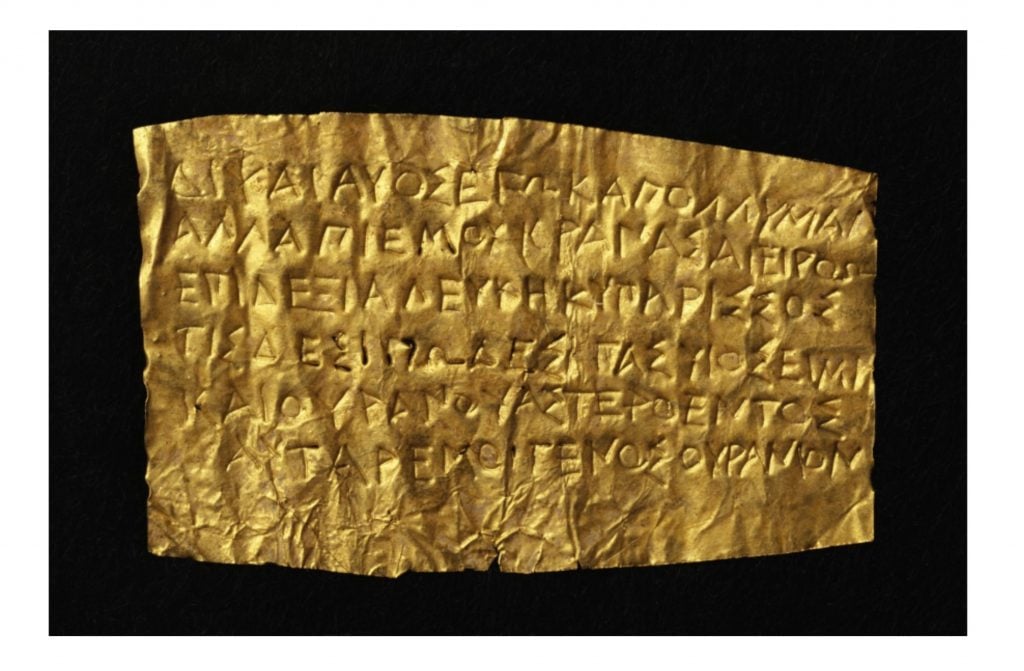

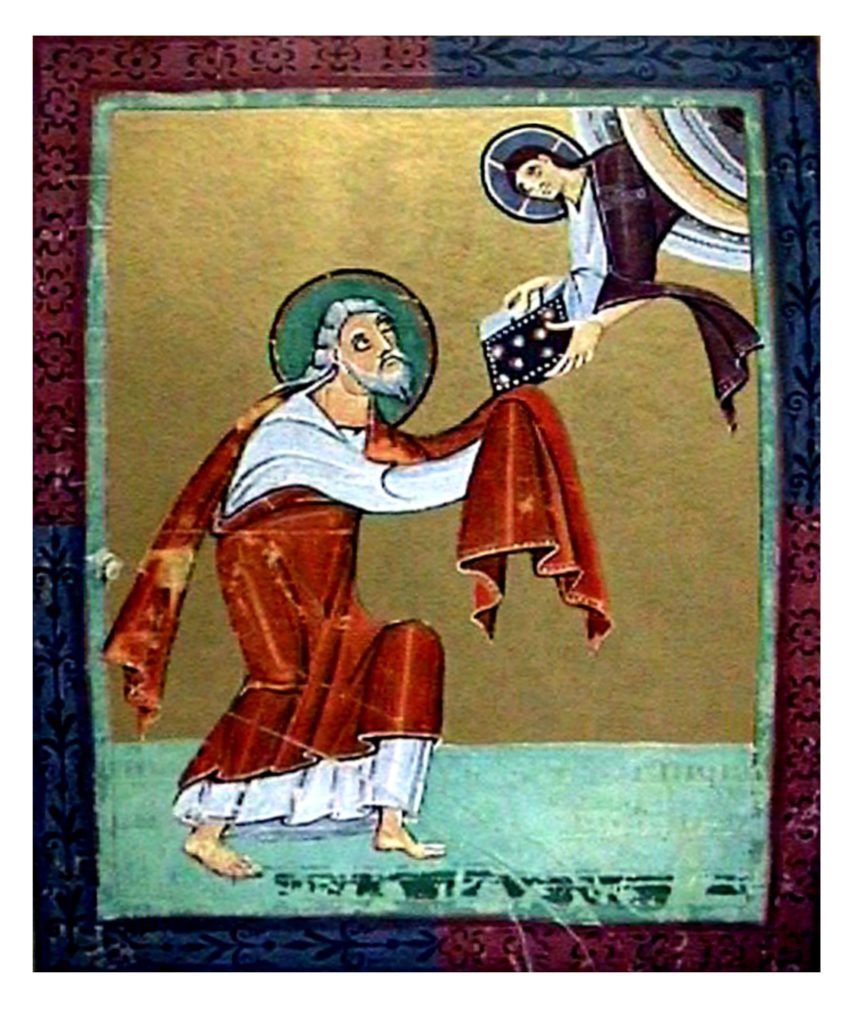

On the island of Patmos just off the west coast of what is now Turkey, a Christian named John experienced disturbing visions of the future. He described these in a manuscript that began with the word apokalypsis (Greek for “unveiling”). This became Revelation, the last book in the Christian New Testament (Koester, 2014; Quispel, 1979). The illustration on the right, from the Bamberg Apocalypse, an illuminated manuscript from the 11th Century, shows an angel telling John what he should write:

On the island of Patmos just off the west coast of what is now Turkey, a Christian named John experienced disturbing visions of the future. He described these in a manuscript that began with the word apokalypsis (Greek for “unveiling”). This became Revelation, the last book in the Christian New Testament (Koester, 2014; Quispel, 1979). The illustration on the right, from the Bamberg Apocalypse, an illuminated manuscript from the 11th Century, shows an angel telling John what he should write:

The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave unto him, to shew unto his servants things which must shortly come to pass; and he sent and signified it by his angel unto his servant John (Revelation 1:1)

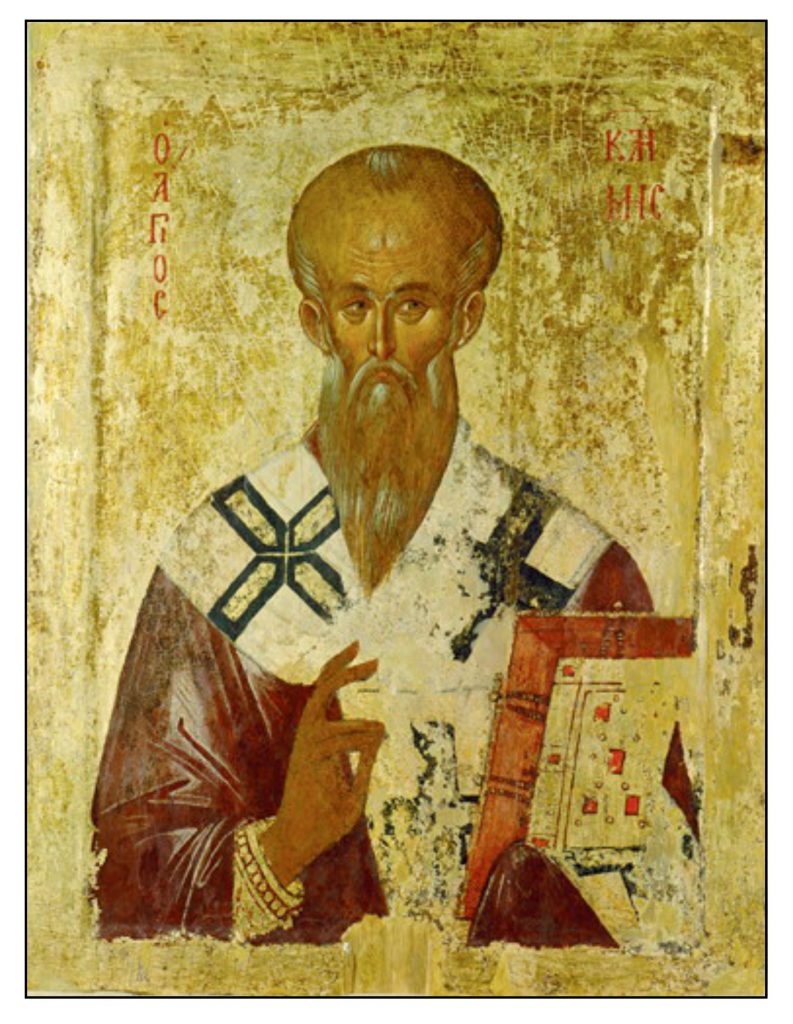

For many years, Christian scholars assumed that John the Apostle, the youngest of Christ’s disciples, was the author of Revelation, the Gospel of John and the three Epistles of John. Most modern scholars consider it unlikely that he wrote any of these works. They suggest three separate authors one for the gospel, one for the three epistles, and one for the apocalypse. One telling point is that each author describes the end-times very differently. For example, the Antichrist is mentioned in the epistles (e.g. 1 John 2:18), but not in the apocalypse. The author of Revelation was probably a Jewish-Christian prophet living in Asia Minor – John of Patmos. He may have written the book over many years. One suggestion is that he began writing as a Jew and later converted to Christianity (Koester, 2014, pp 68-71).

The visions described by John are stunning in their force and detail. The Whore of Babylon, the Seven-Headed Beast, and the Four Horsemen have become part of our collective consciousness.

Revelation is the most interpreted and least understood book of the Christian Bible (Quispel, 1979; Koester, 2014). Some have interpreted the visions as describing the troubled time in which they were experienced. The Seven-Headed Beast could then represent Rome (with its seven hills, or its seven emperors), and the Rider on the White Horse could represent the Parthians who threatened the peace of the Middle East. Others have considered the visions as prophesying the later history of the Christian Church. The Whore of Babylon was the papacy of Rome for Protestants and the heresies of the Reformation for Catholics. Others believe that Revelation foretells the Last Days, that are yet to come, when Christ will judge both the quick and the dead.

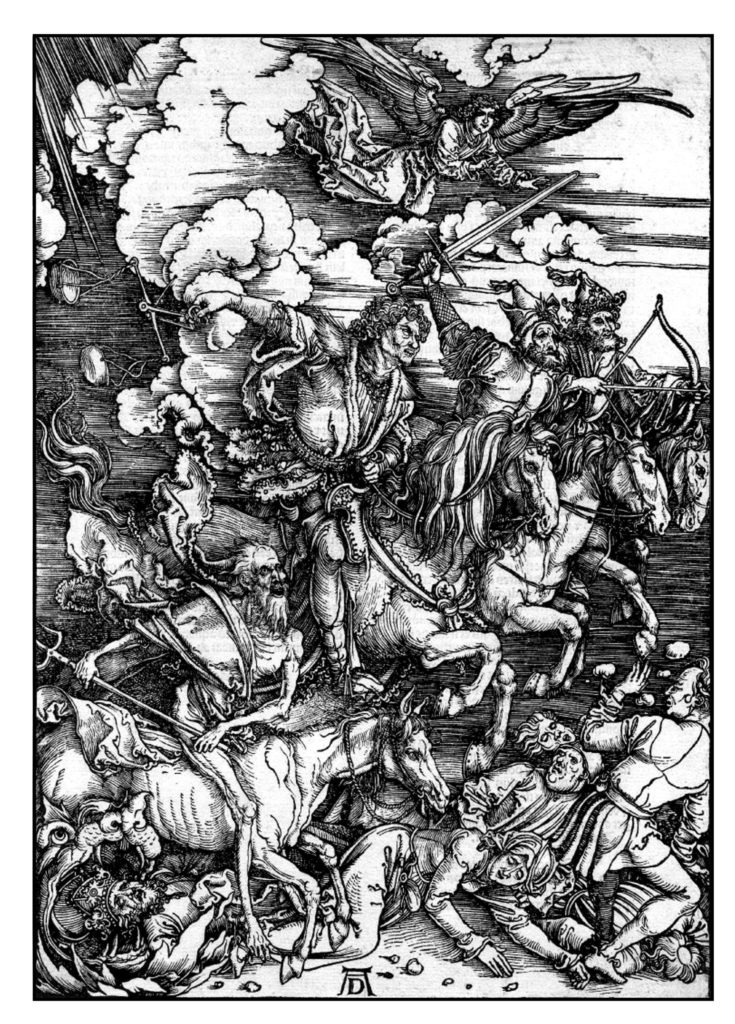

John’s first vision was of the Lord seated upon a throne in Heaven. This is illustrated below in the 11th-Century Bamberg Apocalypse, and in the 1498 woodcut by Albrecht Dürer. Around the throne were four beasts in the form of Man, Lion, Ox and Eagle, probably representing the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. Around them were four and twenty elders, clothed in white and wearing crowns of gold. In the Lord’s right hand was a book “sealed with seven seals.” The structure of this book is not clear. Perhaps it is made up of seven scrolls one rolled up within the other (Quispel, 1979, p 51). A mystical lamb appears and proceeds to open each of the seals.

The Four Horsemen

As the first four seals are opened four horsemen appear:

And I saw when the Lamb opened one of the seals, and I heard, as it were the noise of thunder, one of the four beasts saying, Come and see.

And I saw, and behold a white horse: and he that sat on him had a bow; and a crown was given unto him: and he went forth conquering, and to conquer.

And when he had opened the second seal, I heard the second beast say, Come and see.

And there went out another horse that was red: and power was given to him that sat thereon to take peace from the earth, and that they should kill one another: and there was given unto him a great sword.

And when he had opened the third seal, I heard the third beast say, Come and see. And I beheld, and lo a black horse; and he that sat on him had a pair of balances in his hand.

And I heard a voice in the midst of the four beasts say, A measure of wheat for a penny, and three measures of barley for a penny; and see thou hurt not the oil and the wine.

And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see.

And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth. (Revelation 6:1-8)

Only the fourth horseman is clearly identified by John as Death. The color of his horse has been interpreted as “pale,” although the Greek chloros is actually better translated as “green.” Perhaps John envisioned a sickly pale green color. The identity of the other three is unknown (reviewed by Koester, 2014, pp 392-398; and in Wikipedia). The rider of the black horse with his scales for weighing and pricing food was almost certainly Famine. The rider of the Red Horse was probably War. The first horsemen has been interpreted in many ways. Perhaps he is Christ, perhaps the Antichrist. Some have considered him as Conquest though this seems to overlap with the rider of the Red Horse. Pestilence or plague seems the most reasonable interpretation. His arrows could then represent the transmission of infection.

The most famous depiction of the Four Horsemen is the 1498 woodcut of Albrecht Dürer, illustrated on the right. The first three horsemen look like mercenary warriors from the Hundred Year War. Death is a skeletal figure riding an emaciated horse. He clears the world of those who die from pestilence, war and famine.

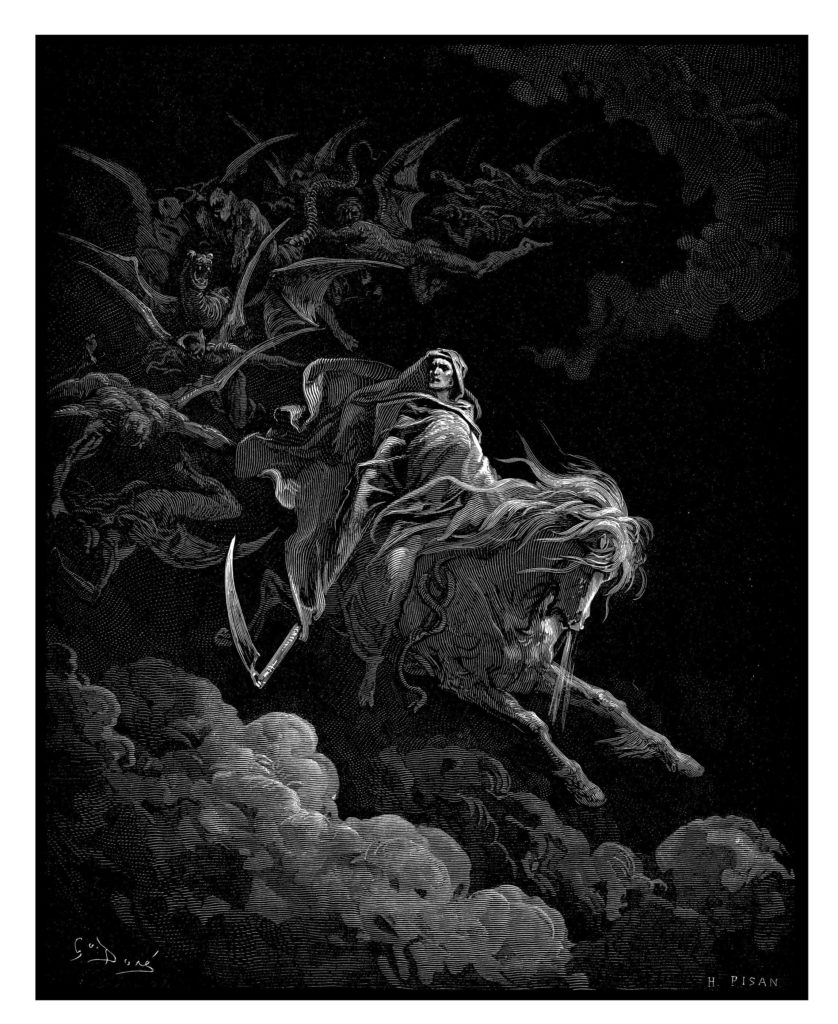

The 1865 wood-engraving by Héliodore Pelan based on a drawing by Gustave Doré gives Death a more majestic appearance, and grants him the scythe that has become his symbol. The scythe refers the apocalyptic passages in the Gospels that consider the final harvest of human souls. Doré also depicts the dark shades of Hades that John saw following after Death.

Pale Horse, Pale Rider

In 1918 Katherine Anne Porter almost died from the Great Influenza while she was in Denver working as a journalist (Barry, 1963). In 1939 she published Pale Horse, Pale Rider a short novel about that experience. In the novel she calls herself Miranda (from the Latin, “to be wondered at”). Pale Horse, Pale Rider was published together with two other stories – Old Mortality and Noon Wine – and gave its title to the collection.

The novel opens with a dream. Miranda is about to go riding, but she cannot decide which horse to borrow for a journey she does not wish to take. She decides against Miss Lucy “with the long nose and the wicked eye,” and Fiddler “who can jump ditches in the dark,” and choses Graylie “because he is not afraid of bridges.” These horses are those that were ridden long ago by Amy, the wife of Miranda’s Uncle Gabriel. Amy was a beautiful and spirited young woman, who committed suicide before Miranda was born. Her story was told in Old Mortality, one of several Miranda stories.

In the dream Miranda must go riding with a stranger who has been hanging about the place. She mounts Graylie, and urges him on. They fly off, over the hedge and the ditch and down the lane:

The stranger rode beside her, easily, lightly, his reins loose in his half-closed hand, straight and elegant in dark shabby garments that flapped upon his bones. (Porter, 1939, p 181)

Suddenly, she pulls Graylie up, the stranger rides on, and Miranda wakes up.

She remembers the events of the day before, particularly her visit to the infirmary at the army camp, and her tryst with her new boyfriend Adam, a young and handsome soldier about to be sent to France. She is not feeling well, but goes to work and once again meets Adam.

The next day she feels quite ill, and is seen by a doctor who prescribes some medications and says he will check on her later. Adam comes to see her and comforts her. They talk of their love for each other, about the war and about old songs they had heard when they were younger. One of these is a spiritual that began “Pale horse, pale rider, done taken my lover away.” The doctor returns and arranges for Miranda to be admitted to hospital. She has contracted influenza, perhaps from her visit to the infirmary.

While in hospital Miranda comes close to death but survives

Silenced she sank easily through deeps under deeps of darkness until she lay like a stone at the farthest bottom of life, knowing herself to be blind, deaf, speechless, no longer aware of the members of her own body, entirely with-drawn from all human concerns, yet alive with a peculiar lucidity and coherence; all notions of the mind, the reasonable inquiries of doubt, all ties of blood and the desires of the heart, dissolved and fell away from her, and there remained of her only a minute fiercely burning particle of being that knew itself alone, that relied upon nothing beyond itself for its strength; not susceptible to any appeal or inducement, being itself com-posed entirely of one single motive, the stubborn will to live. This fiery motionless particle set itself unaided to resist destruction, to survive and to be in its own madness of being, motiveless and planless beyond that one essential end. (pp 252-3).

She has a vision of a place reached by crossing a rainbow bridge. Graylie was not afraid of bridges. There Miranda sees in the shimmering air “a great company of human beings,” all the people she had known in life. From this apparent heaven she returns to the reality of the hospital. She has miraculously comeback from the dead. She lives up to her name – someone to be wondered at.

In her convalescence she learns that Adam had also became ill, probably having caught the disease from her. However, though Miranda had survived, Adam had died.

Outside the bells are ringing to celebrate the end of the war. As Miranda prepares to leave the hospital, she requests some essentials to begin her new life:

One lipstick, medium, one ounce flask Bois d’Hiver perfume, one pair gray suede gauntlets without straps, two pairs gray sheer stockings without clocks … one walking stick of silvery wood with a silver knob. (p 262).

She will be pale and elegant like the rider she dreamed about at the beginning of her illness, the rider that done take her love away. She has been irretrievably marked by death. As she leaves the hospital Miranda thinks

No more war, no more plague, only the dazed silence that follows the ceasing of the heavy guns; noiseless houses with the shades drawn, empty streets, the dead cold light of tomorrow. Now there would be time for everything. (p 264)

Life is now defined by what it is not – no war, no plague, no noise, no light. Porter’s words recall Wilfred Owen’s 1917 poem Anthem for Doomed Youth which begins with the “monstrous anger of the guns” and ends with “each slow dusk a drawing down of blinds” (Owen, 1985, p 76). Much poetry was written about the terrible loss of life in the Great War. Very little is concerned with the great epidemic of influenza that marked its ending (Crosby, 1989; Fisher, 2012).

Miranda’s final claim “Now there would be time for everything” is the tragedy of the book. She is now free to do as she wishes but there is nothing that she wishes to do.

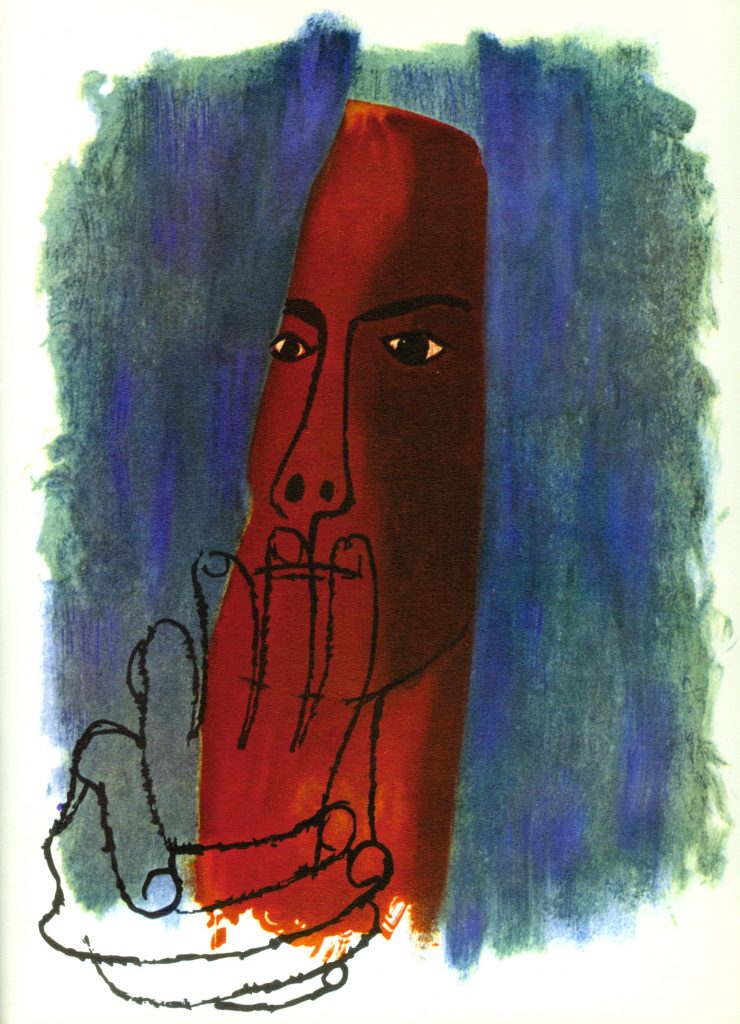

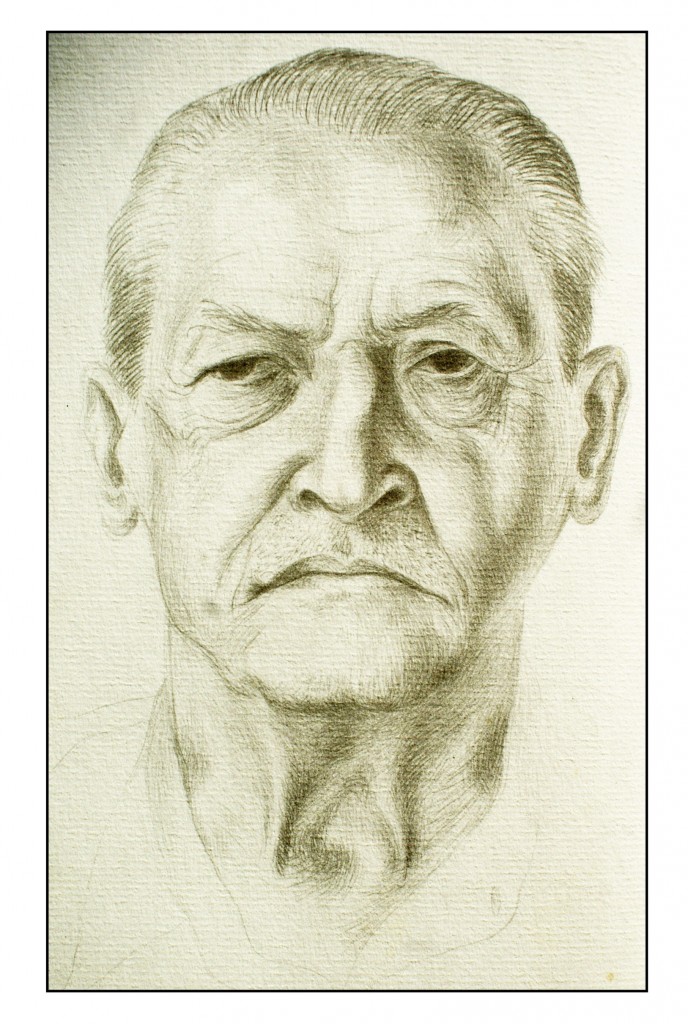

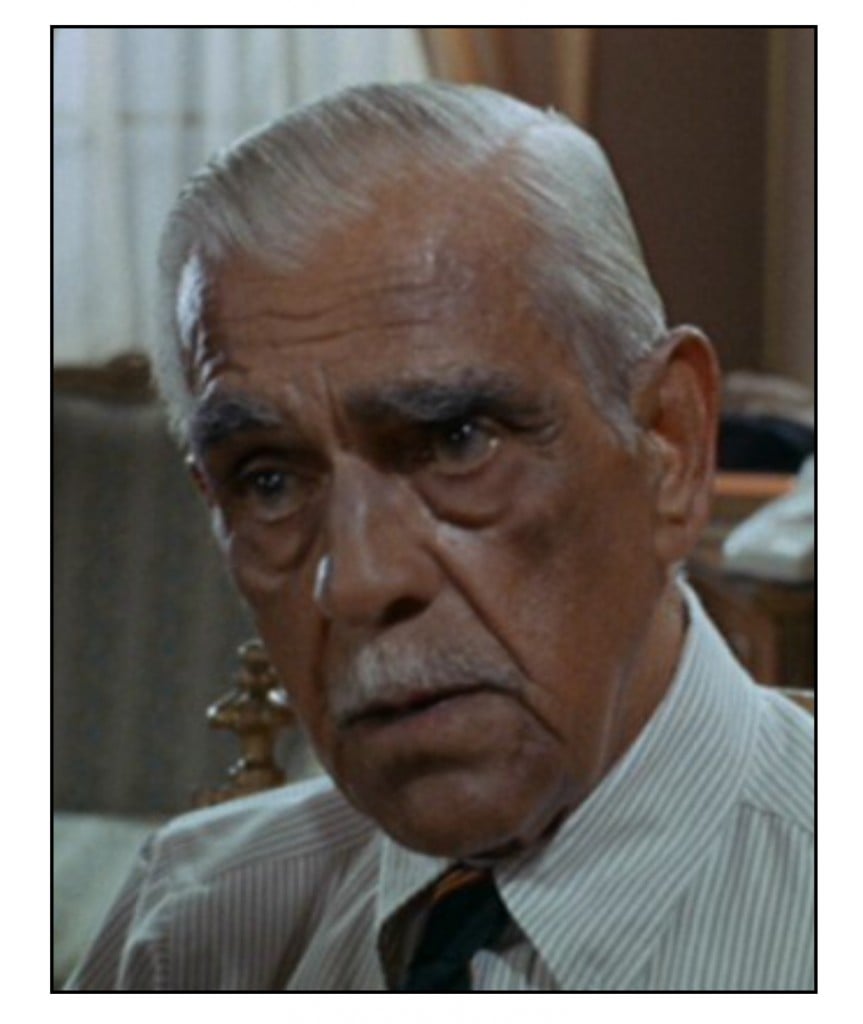

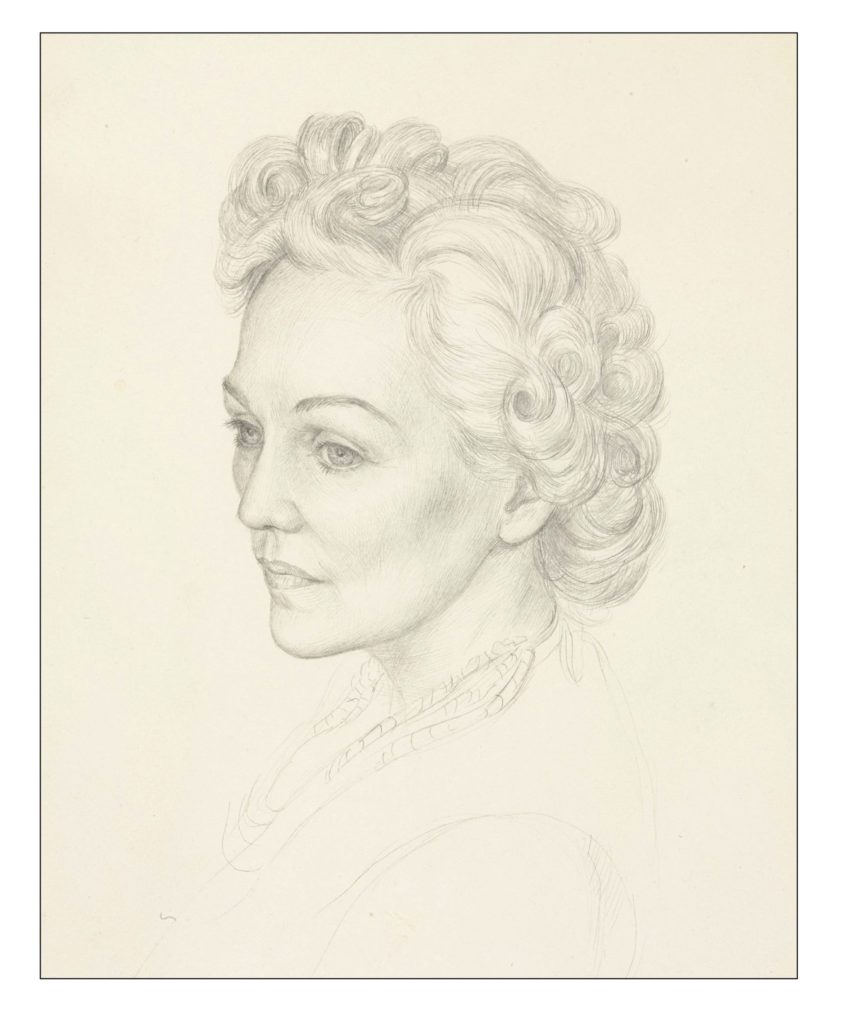

Porter spent many years before she fully recovered from her experience in Denver. She did not publish her first stories until 1930, and Pale Horse, Pale Rider did not come out until 1939. Some sense of Miranda’s feelings at the end of that book is perhaps present in the 1942 portrait drawing of Porter by Paul Cadmus.

Porter spent many years before she fully recovered from her experience in Denver. She did not publish her first stories until 1930, and Pale Horse, Pale Rider did not come out until 1939. Some sense of Miranda’s feelings at the end of that book is perhaps present in the 1942 portrait drawing of Porter by Paul Cadmus.

The Great Influenza

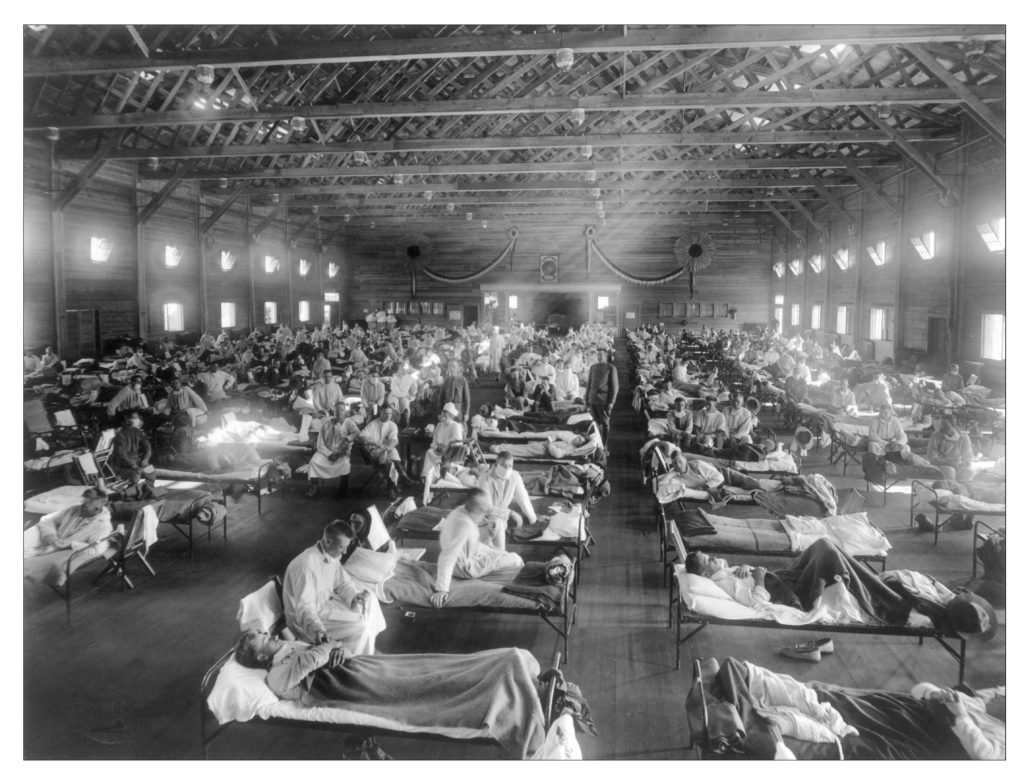

The influenza that almost killed Katherine Anne Porter swept across the world between 1918 and 1921 (Barry, 2004; Crosby, 1989; Spinney, 2017; Taubenberger & Morens, 2006). No one is sure where it began. The first cases were seen in Kansas, and the disease spread rapidly through the US army camps where young men were being trained before going to fight in France.

The following is the iconic image of the epidemic: the make-shift infirmary at Camp Funston, Kansas. The photograph is strangely still. It should be accompanied by the sound of intermittent coughing. The light rakes across the camp cots, randomly selecting one soldier or another, much as the disease would select those who would die. There was no treatment: oxygen would not be used for pneumonia until after the war (Heffner, 2013). About a quarter of the young men in this photo likely died of influenza. More US soldiers died of influenza than during battle.

The disease quickly spread to the battlefields of Europe. None of the combatant-countries wished to acknowledge that their troops were ill. Since the first officially reported cases occurred when the disease spread to Spain, the pandemic was thereafter miscalled the Spanish Flu. In this posting it is called the Great Influenza.

The disease quickly spread to the battlefields of Europe. None of the combatant-countries wished to acknowledge that their troops were ill. Since the first officially reported cases occurred when the disease spread to Spain, the pandemic was thereafter miscalled the Spanish Flu. In this posting it is called the Great Influenza.

The 1918 pandemic was unusual in that it the young and healthy were more susceptible to the disease than the elderly. This may have been related to the close quartering of the young soldiers. Or it might have been caused by an overly reactive immune system.

Coronavirus COVID-19 acts similarly to the influenza virus in terms of its spread through airborne droplets, and in terms of how its major morbidity is due to a viral pneumonia. The coronavirus differs from the Great Influenza in that it affects the elderly more than the young. Nevertheless, we should look to the Great Influenza in terms of what might happen in our current pandemic.

A pandemic is characterized by two main parameters. The contagiousness of the disease is measured by the basic reproduction number (R0). This is the number of new people that will become infected from one individual patient. If R0 is less than 1 the disease dies out; if it is greater than 1 the disease spreads exponentially through the population. The virulence of the disease is assessed by the case fatality rate (CFR). This measures the proportion of infected patients that die.

For the Great Influenza R0 was about 2 (Ferguson et al. 2006), and the CFR was about 2.5% (Taubenberger & Morens, 2006). We do not yet know for sure how the present coronavirus COVID-19 compares. Early data from China suggest that R0 is about 2, and the CFR about 5% (Wu et al., 2020). Since we have not yet done sufficient testing to be sure of the number of cases in the population, the CFR is likely overestimated. Most of the tested cases are patients who have been severely symptomatic. If there is a significant number of asymptomatic (and untested) cases, the CFR will be lower (discussed extensively on the World in Data website). It might approach the CFR estimated for the Great Influenza, but it will be at least an order of magnitude greater than seasonal flu (<0.1%).

For those who wish to consider all the other great epidemics of human history, Wikipedia has listed their estimated values for R0 and CFR.

The numbers for COVID-19 Pandemic indicate we must be extremely cautious so as not to endure a repeat of the Great Influenza. Since stories are often more convincing than numbers, we can briefly consider the effect of the Philadelphia’s Liberty Loan Parade on September 23, 1918. Despite warnings about the influenza, the city went ahead with a huge parade to drum up support for the US war effort. A few days after the parade, hundreds of people became ill. Soon the number of ill patients increased. Hospitals rapidly became overcrowded and unable to take new cases. By the end of the years the number of cases exceeded 100,000 and the number of dead approached 13,000, over 1% of the city’s population (Barry, 2004, pp 220-227; Kopp & McGovern, 2018)). In contrast after the first recorded cases of influenza in St Louis, that city quickly instituted measures against the spread of the disease, such as closing schools and banning public gatherings. The number of deaths in St Louis per 100,000 population during the epidemic was less than half that in Philadelphia (Hatchett et al, 2007).

In Philadelphia and across the world morticians and gravediggers rapidly became overwhelmed and bodies began to pile up in the streets. In Rio de Janeiro, Jamanta, a famous carnival reveller, commandeered a tram and a luggage car and swept through the city picking up bodies and delivering them to the cemetery (Spinney, 2017, p. 54-55).

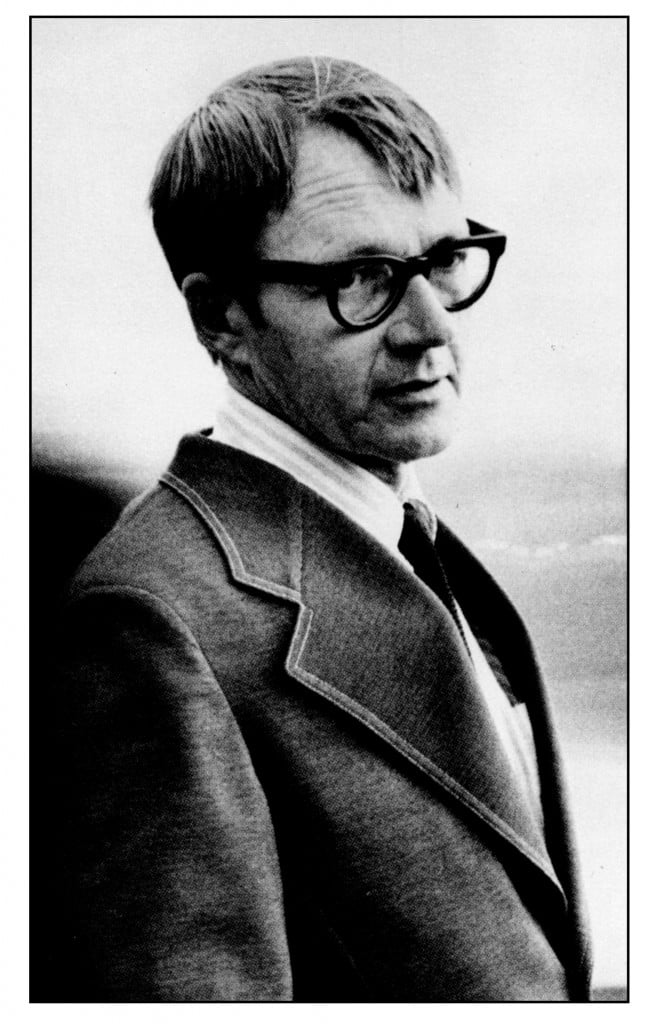

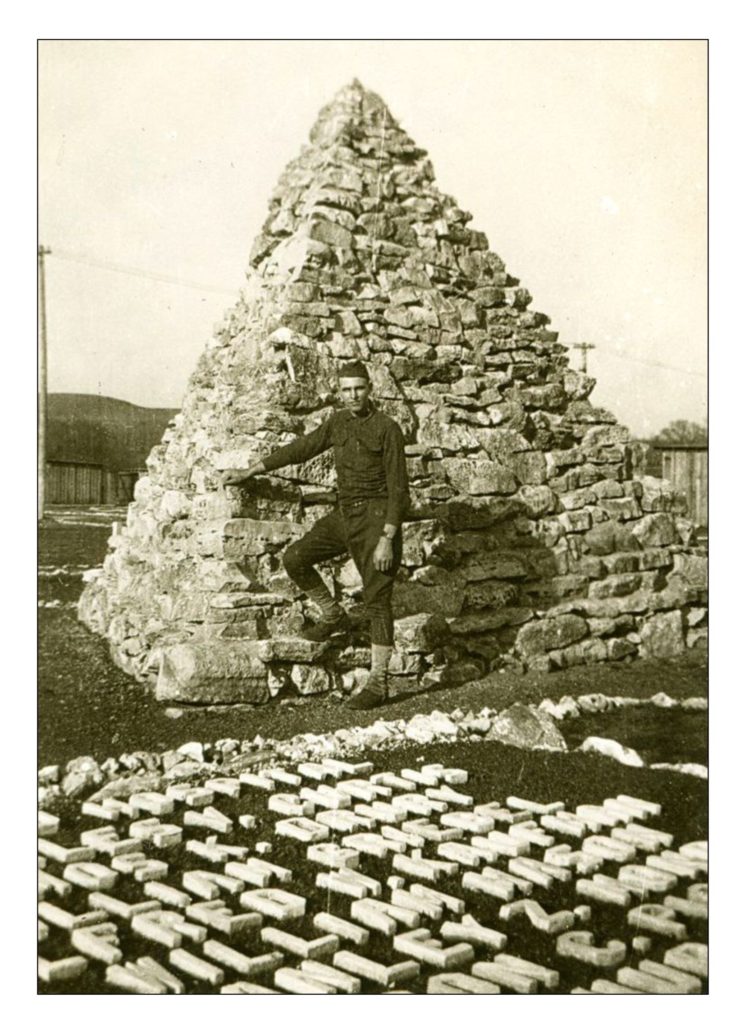

Despite its death toll, the Great Influenza was largely ignored by historians until the possibility of new influenza pandemics became real toward the end of the 20th Century. Thousands of monuments memorializing those who died in the Great War exist all over the world. Monuments to those who died of influenza are scarce, even though those who died of the disease outnumbered those who died in battle. The soldiers at Camp Fenton erected their own memorial to their colleagues who had died of the influenza (illustrated on the right, with its designer Henry Hardy). The monument was a simple pyramid of piled up stones with the names of the victims written in smaller stones on the grass. The camp and its monument have been long ago abandoned.

Despite its death toll, the Great Influenza was largely ignored by historians until the possibility of new influenza pandemics became real toward the end of the 20th Century. Thousands of monuments memorializing those who died in the Great War exist all over the world. Monuments to those who died of influenza are scarce, even though those who died of the disease outnumbered those who died in battle. The soldiers at Camp Fenton erected their own memorial to their colleagues who had died of the influenza (illustrated on the right, with its designer Henry Hardy). The monument was a simple pyramid of piled up stones with the names of the victims written in smaller stones on the grass. The camp and its monument have been long ago abandoned.

One of the reasons for the lack of attention that the Great Influenza received may have been that it did not fit with any overarching narrative. Though many died, they did not die for some noble cause. The disease was largely random it its killing.

The Black Death

Even though it did not kill so many, the Black Death had a far greater impact on our history. It shattered the society of the Middle Ages, disrupting the feudal system, and questioning the power of the Church. Part of this impact was due to the Bubonic Plague being far more virulent than either the influenza or the coronavirus. The Case Fatality Rate during the Black Death was over 30%. The disease was caused by a bacterium Yersinia pestis, which is endemic in rats and transmitted to human beings by fleas. The infected rats and their fleas came to Europe from the East on merchant ships. The plague began in port cities such as Naples, Venice and Genoa, are rapidly spread throughout Europe (McMillen, 2016; Snowden, 2019).

Nowadays we have antibiotics that can kill the bacteria that causes the Bubonic Plague. Furthermore, we understand how it is transmitted and can prevent this by controlling human exposure to rats and fleas. In the 14th Century there was nothing to do but flee. This flight actually increased the spread of the disease, which was carried by the fleas on all those who ran away.

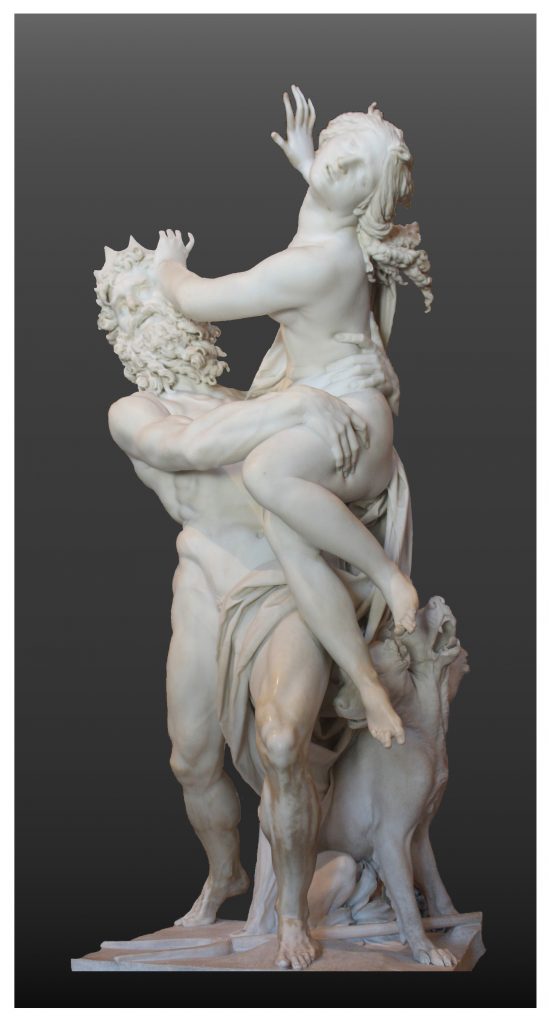

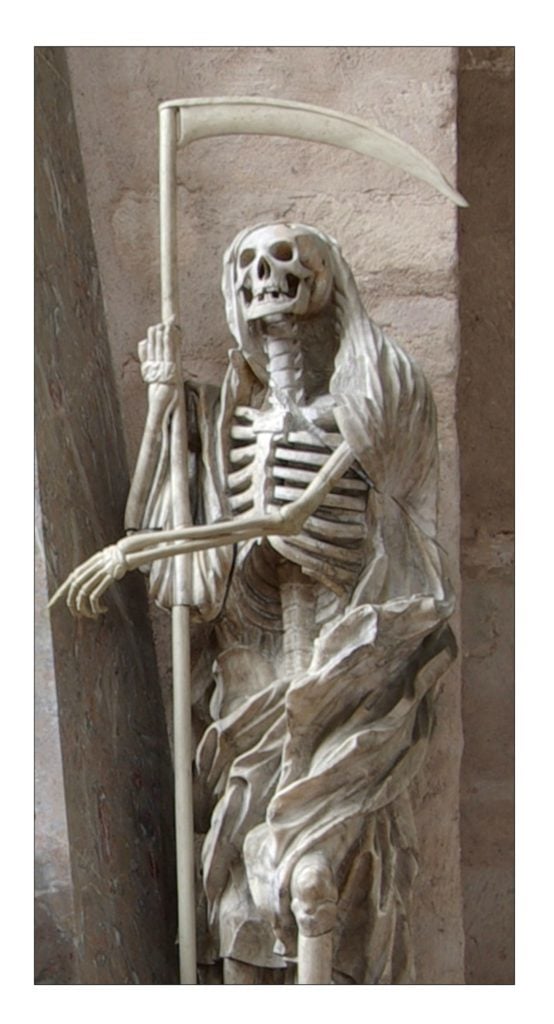

The Black Death bequeathed us with our most potent image of death as a skeletal figure, often clad in a shroud or black cloak and carrying scythe – the “grim reaper.” Such figures were often portrayed leading various people from all stations of life in a “dance of death.” The statue illustrated on the right is from the tomb in Trier Cathedral of Johann Philipp von Wallerdorff who died in 1768.

The Black Death bequeathed us with our most potent image of death as a skeletal figure, often clad in a shroud or black cloak and carrying scythe – the “grim reaper.” Such figures were often portrayed leading various people from all stations of life in a “dance of death.” The statue illustrated on the right is from the tomb in Trier Cathedral of Johann Philipp von Wallerdorff who died in 1768.

Many considered the Black Death as God’s punishment for humanity’s sins, and decided that a great return to God was necessary. Yet the plague had randomly killed both saint and sinner. Others thought that the plague was God’s demonstration that the Church had gone astray and needed to be reformed. Yet both priests and parishioners were equally affected.

And so, a few came to the idea that perhaps there was no God. The only justice in the world was at the hand of human beings. And their only recourse was themselves. And if they could ultimately survive the plague, they could perhaps settle on a different world, where reason ruled instead of faith.

The Seventh Seal

In Revelation after the four horsemen, the fifth and sixth seals are opened. These bring forth to John a vision of the Christian Martyrs, and then a vision of all those who had been saved by faith in Christ. Finally, the last seal is opened:

And when he had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour. (Revelation 8:1)

Christians interpret the silence as representing the awe that occurs when one realizes the greatness of God and his program for the future. Ingmar Bergman considered it differently. Much of his work is concerned with the silence of God. All our prayers no matter how fervent are met with silence. He made this the subject of a trilogy of films: Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1963) and The Silence (1963).

The idea is also at the heart of his earlier 1957 film The Seventh Seal. The quotation from Revelation about the opening of the seventh seal and the silence in heaven begins the film. A knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) has just returned to Sweden from the Crusades. He has brought with him a game of chess that he learned in Palestine. All of Europe is in the grip of the Black Death. On a beach Antonius prays to God. After his prayer, Death (Bengt Ekerot) appears. Antonius challenges Death to a game of Chess to decide his fate. The following is a clip from the movie. The sound of the waves goes silent when Death appears.

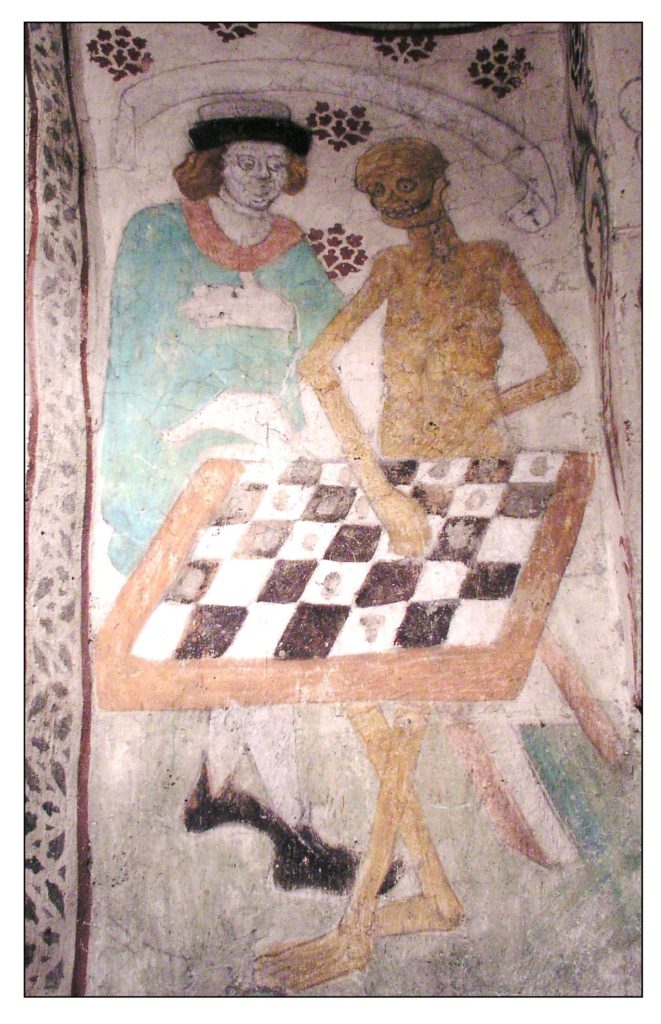

Bergman based the idea of the game of chess from a 1480 fresco (right) painted by Albertus Pictor in the Täby Church near Stockholm. As the film proceeds, Death ultimately wins the game, and leads Antonius and his family off in a dance of death. The film is not accurate historically: the crusades ended long before the Black Death. However, it is one of our most vivid depictions of human mortality.

Bergman based the idea of the game of chess from a 1480 fresco (right) painted by Albertus Pictor in the Täby Church near Stockholm. As the film proceeds, Death ultimately wins the game, and leads Antonius and his family off in a dance of death. The film is not accurate historically: the crusades ended long before the Black Death. However, it is one of our most vivid depictions of human mortality.

Playing Chess with Death

Death is now among us. Not in as the dark figure portrayed by Bengt Ekerot, but in the form of a coronavirus epidemic. The disease is not as virulent as the Black Death. However, it is likely just as contagious and just as virulent as the virus that caused the Great Influenza. How do we prevent what happened in 1918 when Death took millions of people before their time?

How do we play our game of chess with Death? We still have no specific treatment, and there is as yet no vaccine. Unlike in 1918, however, we now have oxygen therapy and, if necessary, artificial ventilation. These procedures can help patients with pneumonia survive until their immune systems can finally destroy the virus. Furthermore, we have monitors such as finger oximeters that can determine when oxygen therapy is needed.

What is most important is to inhibit the spread of the disease in the population. The most powerful means to do this involves identifying all patients with the disease, tracing all people who have come in contact with these patients, testing these contacts, and quarantining both the patients and their contacts (whether or not they are infected) until they are no longer contagious. Since we have tests that are reasonably specific for the virus, this approach is definitely possible, and is being used successfully in China and in South Korea.

In the absence of contact tracing, we can limit the spread of the disease by staying away from our fellows beyond the distance that airborne drops can travel: “physical distancing” (a more appropriate term than “social distancing”). Physical distancing can certainly slow down the spread of the disease so that hospital facilities for treating those patients that develop pneumonia do not become overwhelmed. However, it will ultimately have to be replaced with contact tracing. Or the Dance of Death will continue.

Despite our best efforts many people will die in the pandemic. Though we know we have to die sometime, we generally believe that this will not be tomorrow. Nowadays death is closer. We need to come to terms with it. Through whatever stories, dreams and visions we can muster. We cannot play chess well without equanimity.

References

Barry, J. M. (2004). The great influenza: The epic story of the deadliest plague in history. New York: Viking.

Crosby, A. W. (1989/2003). America’s forgotten pandemic: The influenza of 1918. Cambridge England: Cambridge University Press.

Ferguson NM; Cummings DA; Fraser C; et al. (2006). Strategies for mitigating an influenza pandemic. Nature, 442 (7101), 448–452.

Fisher, J. E. (2012). Envisioning disease, gender, and war: Women’s narratives of the 1918 influenza pandemic. New York: Palgrave Macmillan

Hatchett, R. J.; Mecher, C. E.; & Lipsitch, M. (2007). Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104, 7582–7587.

Heffner, J. E. (2013). The story of oxygen. Respiratory Care, 58, 18-31.

Koester, C. R. (2014). Revelation: a new translation with introduction and commentary. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014.

Kopp, J., & McGovern, B. (2018). 100 years ago, ‘Spanish flu’ shut down Philadelphia – and wiped out thousands. PhillyVoice, September 20 and 27, 2018.

McMillen, C. W. (2016). Pandemics: a very short introduction. New York: Oxford University Press.

Owen, W. (Edited by Stallworthy, J., 1985). The poems of Wilfred Owen. London: Hogarth Press.

Porter, K. A. (1939). Pale horse, pale rider: Three short novels. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Quispel, G. (1979). The secret Book of Revelation: The last book of the Bible. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Snowden, F. M. (2019). Epidemics and society: From the Black Death to the present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Spinney, L. (2017). Pale rider: The Spanish flu of 1918 and how it changed the world. London: Johnathan Cape.

Taubenberger, J. K., & Morens, D. M. (2006) 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics Emerging Infectious Diseases, 12, 15-22.

West, R. B. (1963). Katherine Anne Porter: American Writers 28. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wu, J.T., Leung, K., Bushman, M. et al. (2020). Estimating clinical severity of COVID-19 from the transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China. Nature Medicine 26, 506–510.