Mitchell and Riopelle

From February 18 to May 6, 2018, the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) is presenting an exhibition of the paintings of Joan Mitchell and Jean-Paul Riopelle entitled Mitchell/Riopelle: Nothing in Moderation. This is the first time that many of these paintings have been seen together. The paintings are stunning, the relations between them fascinating.

Abstract Expressionism

The abstract expressionist movement in painting began in New York in the 1940s (Anfam, 1990, Sandler, 1970). Among its major artists were Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Robert Motherwell. Each artist had his own particular style, but they all attempted to convey meaning and emotion without recourse to representation. The Americans promoted the development of abstract expressionism as their particular artistic “triumph” (Sandler, 1970), and other abstract artists working later or in other countries have lived too long without proper recognition. Among these are Joan Mitchell and Jean-Paul Riopelle.

Riopelle developed his technique independently of the New York artists. He had studied with Paul-Émile Borduas in Montreal, who had extended the ideas of surrealism into a movement called Les Automatistes. Finding the society of French Canada unreceptive to his new art, Riopelle moved to Paris. Mitchell had been impressed by the New York Abstract Expressionists, particularly de Kooning and Kline, but began to evolve her own particular style after visiting France.

In parallel to New York, Paris had developed a similar artistic movement called Abstraction Lyrique (Moszynska, 1990, p 120). This differed from the New York movement mainly by rejecting the geometric approaches, such as those of Barnett Newman or Josef Albers, which was considered “cold abstraction.” Mitchell and Riopelle painted most of their major works in France, and could be considered proponents of this type of abstraction. However, the term is ambiguous since “lyric abstraction” was also used to describe a group of New York artists in the 1960s.

Lives of the Artists

Mitchell and Riopelle came from vastly different backgrounds. Mitchell (1925-1992) was born into a wealthy family in Chicago. Her maternal grandfather Charles Strobel was an accomplished engineer who had designed many of the early Chicago steel-frame skyscrapers. Her mother was a poet and co-editor of Poetry, her father a very successful dermatologist and amateur painter. Riopelle (1923-2002) was from the middle class. His father was a builder and Riopelle started out with the idea of becoming an architect. For both Riopelle and Mitchell, early teachers inspired their artistic talents, and they both decided to pursue painting – Mitchell in New York with the Abstract Expressionists, and Riopelle in Montreal with the Automatistes. Mitchell visited France in 1948 but began her painting career in New York. Riopelle moved to Paris in 1948 and soon became recognized for his large abstract paintings, such as Pavane (1954) (not in the AGO exhibition) but reproduced below:

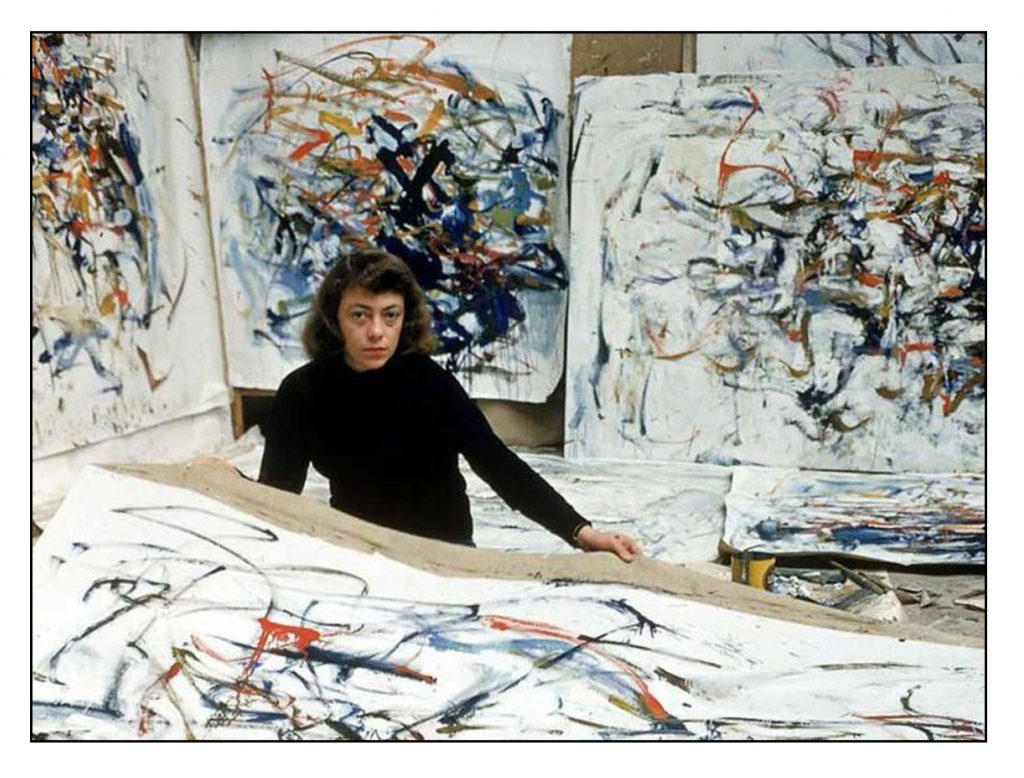

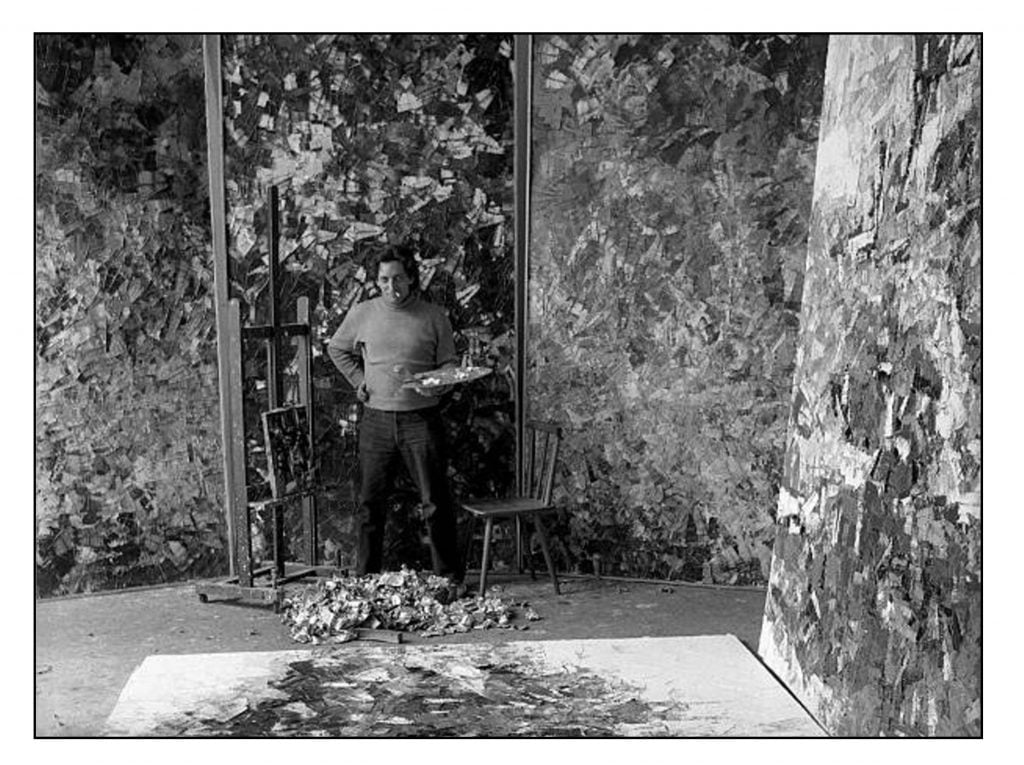

Mitchell and Riopelle met in Paris in 1955. Both were married, but Riopelle was living apart from his wife and Mitchell had divorced her husband. They were mutually attracted and spent time together, ultimately moving into a shared studio apartment in Paris in 1959. Paris was the city where art was created and love was enjoyed. Mitchell considered the beginning of their relationship in terms of Piaf’s famous La Vie en Rose. Their relationship was passionate and tumultuous, productive and persistent. Below are 1956 photographs of the artists in their Paris studios:

Mitchell and Riopelle met in Paris in 1955. Both were married, but Riopelle was living apart from his wife and Mitchell had divorced her husband. They were mutually attracted and spent time together, ultimately moving into a shared studio apartment in Paris in 1959. Paris was the city where art was created and love was enjoyed. Mitchell considered the beginning of their relationship in terms of Piaf’s famous La Vie en Rose. Their relationship was passionate and tumultuous, productive and persistent. Below are 1956 photographs of the artists in their Paris studios:

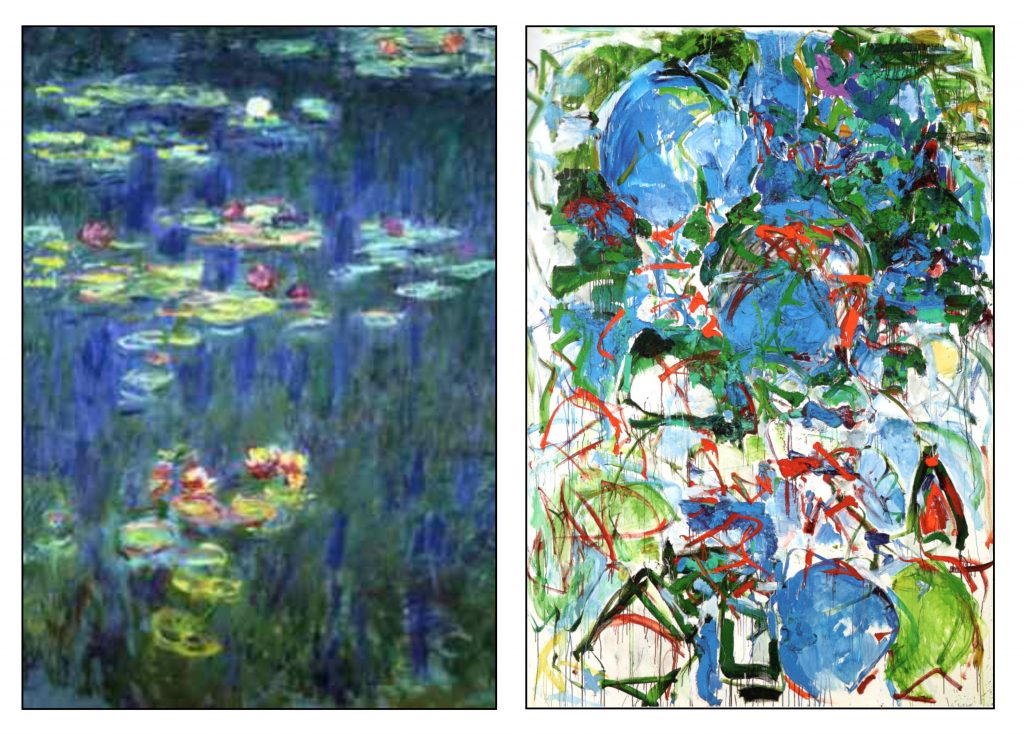

In 1967 Mitchell purchased an estate in Vétheuil about 65 km northwest of Paris. This was close to Giverney, where Claude Monet had painted his famous series of Water Lilies, and near a house where Monet had lived before Giverney. Riopelle initially lived at Vétheuil, but he later purchased a separate studio several miles away, and spent much of his time working there or travelling.

The paintings of Riopelle and Mitchell give the same sense of shimmering light as the impressionist works from fifty years before. This is shown in the following illustration which compares a part of a Monet Water Lilies from 1916 to Mitchell’s Mon Paysage (1967). Mitchell’s painting seems to have abstracted the feelings from a landscape of flowers. Not water lilies – but the colors and the feelings are similar.

One might perhaps consider Mitchell’s work as “abstract impressionism.” This formulation has been used to describe some of the later abstract expressionists such as Riopelle, Mitchell, Sam Francis and Patrick Heron, but it never really caught on, and Mitchell disliked the term (Michaud in Martin et al. 2017, p 118).

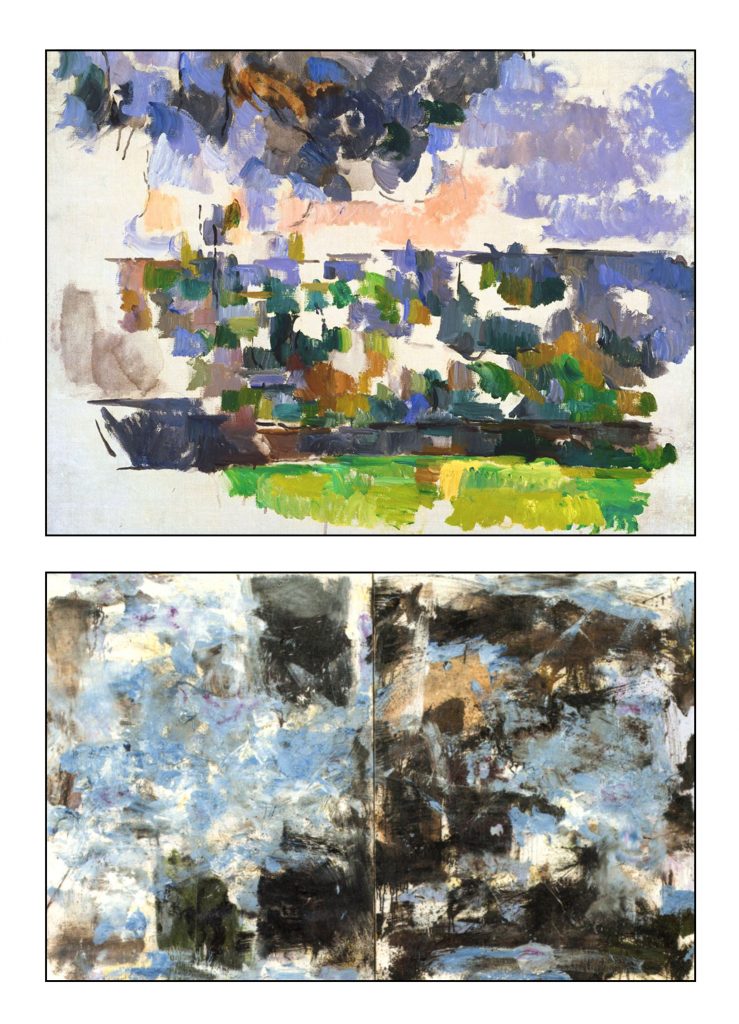

And as for any artist, the sources of present art have many different predecessors. Some of the late Cézanne paintings which pieced together blue and green color-fields to represent the garden at his home Les Lauves in Provence (1906) parcel out a similar experience to Mitchell’s untitled diptych form her 1975 Canada series. Mitchell uses a different palette of colors and her painting is about twice the size, but the feelings evoked and the experiences suggested are very similar: In 1974 Riopelle constructed a studio in the Laurentians in Canada and began to spend more and more time there. Mitchell visited. Some of her later monumental abstract paintings were inspired by the Canadian landscape, such as Canada I (1975) shown below.

In 1974 Riopelle constructed a studio in the Laurentians in Canada and began to spend more and more time there. Mitchell visited. Some of her later monumental abstract paintings were inspired by the Canadian landscape, such as Canada I (1975) shown below.

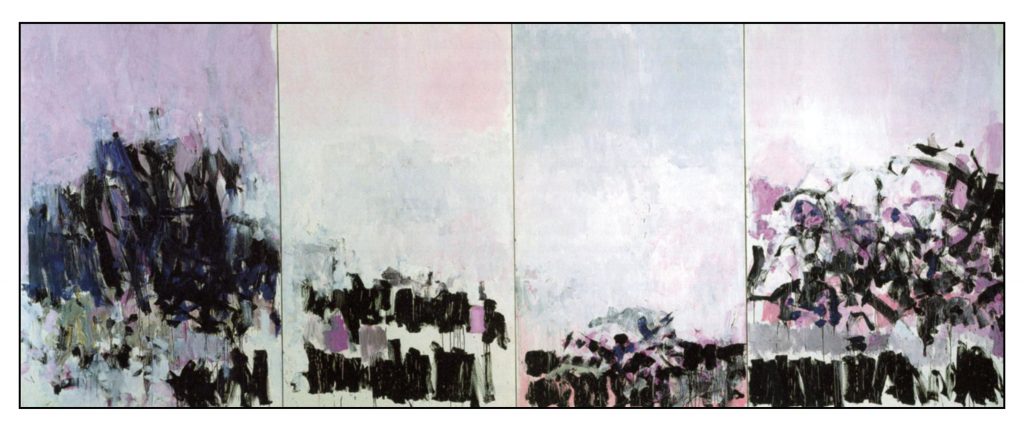

However, the relationship between Mitchell and Riopelle was beginning to fall apart. Mitchell’s large quadriptych Chasse Interdite (1973) was initiated by an angry argument about hunting, which Mitchell deplored and Riopelle enjoyed. In 1978 Riopelle began an affair with Mitchell’s young protégé and assistant Hollis Jeffcoat. In 1979 the relationship between Mitchell and Riopelle ended. Mitchell stayed in France and Riopelle returned to Canada. After their rupture Mitchell painted another quadriptych, bitterly entitled La Vie en Rose (1979). Though not in the AGO exhibition, it is reproduced below:

Abstract Meanings

All paintings convey meaning. However, representational art is far easier to understand than abstract art. The meaning is in the scene, person or object that the painting describes. The style of the painting can highlight certain aspects of this meaning, but ultimately the artist is saying something about what the painting represents.

Abstract art does not directly represent or portray the world. Moszynska (1990, p 7) suggest that abstract art comes from two different approaches. In one the artist starts from an experience of the real world but then simplifies and changes it to highlight its effect on the artist. This gives the viewer a new way of looking at the world. In the other approach the artist starts with some transcendent or mystical idea and tries to give it form. This provides the viewer with some insight into what is beyond any normal sensory experience. Mitchell and Riopelle used the first approach; Barnett Newman and Rothko the second.

Many people give up trying to understand abstract art. The artist provides little help, generally refusing to say what an abstract painting means. Sometimes the paintings are given simple titles, but these often come after the fact, and many paintings remain untitled or simply numbered. The artist insists that the painting means something that could not be expressed in words but only conveyed in paint.

The indefiniteness of abstract paintings has some similarity to music. A piece of music composed without any definite program is appreciated for its melody and rhythm, but most particularly for its emotional effect. William Pater wrote long ago that “All art constantly aspires towards the condition of music” (Pater, 1893). Though he was discussing classical representational painting, his idea fits best with abstract art. Herbert Read proposed that all art involves a response to “harmonies” and “rhythms,” whether they be musical or not:

All art is primarily abstract. For what is aesthetic experience, deprived of its incidental trappings and associations, but a response of the body and mind of man to invented or isolated harmonies? Art is an escape from chaos. It is movement, ordained in numbers; it is mass confined in measure; it is the indetermination of matter seeking the rhythm of life. (Read, 1931, p 42)

The difficulty in understanding an abstract painting can sometimes lead to hostility. Exasperated viewers may claim that a monkey or a three-year old could paint something similarly meaningless. They fear that the artist is putting one over on them.

Perhaps the best approach is to let the paintings directly provide a new sensory experience. This is helped by the large size of many abstract paintings, which can fill the viewer’s field of vision. What emotions do the paintings trigger? Emotions are difficult to put into words. But this does not make them any less powerful, or any less meaningful. The following quotation is from the play Red which brought the art of Rothko to the stage

Wait. Stand closer. You’ve got to get close. Let it pulsate. Let it work on you: let it embrace you, filling your peripheral vision so nothing else exists or has ever existed or will ever exist. Let the picture do its work – But work with it. (Logan, 2009)

The direct sensory and emotional experience of abstract art can be illustrated in two paintings. The first is La Forêt ardente (1955) by Riopelle. The French ardent means “burning” or “passionate.” The experience of the painting is similar to that of being in an autumn forest. The darkness, the colored leaves, and the sky above are all there. But the essence of the experience is its passion.

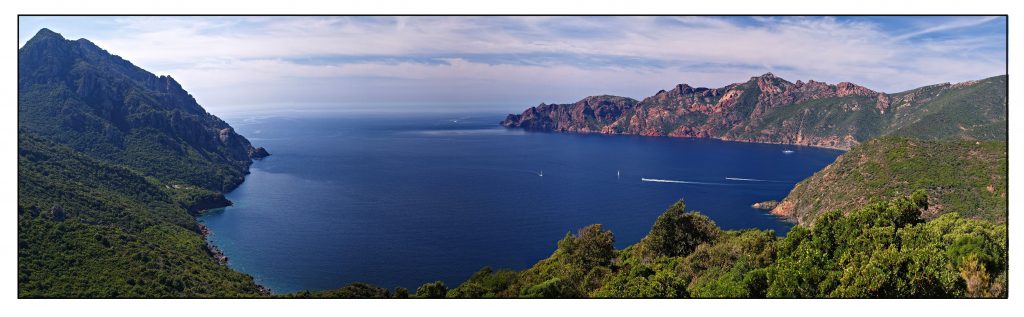

The second painting is Girolata (1964) by Mitchell. Girolata is an isolated village on a bay on the west coast of Corsica. The following is a photograph of the bay by Pierre Bona (2006). And below that is Mitchell’s painting. The experience of the painting is one of serenity. All is right with the world.

In relation to the idea of turning landscape into feelings, one may quote Mitchell’s own words from the introduction to her exhibition at the Whitney Museum in 1974 (Tucker, 1974);

My paintings aren’t about art issues. They’re about a feeling that comes to me from the outside, from landscape.

I would rather leave Nature to itself. It is quite beautiful enough as it is. I do not want to improve it … I could certainly never mirror it. I would like more to paint what it leaves me with.

The painting is just a surface to be covered. Paintings aren’t about the person who makes them, either. My paintings have to do with feeling, yet it’s pretentious to say they’re about feelings, too, because if you don’t get it across, it’s nothing.

Differences

When one compares the paintings, it is important to realize that the work of both painters, particularly that of Riopelle, evolved through different styles. So we must talk in terms of artistic tendencies rather than fixed techniques – dispositions rather than rules. And it will be easy to find contradictory examples.

Mitchell always used a brush, whereas Riopelle used a palette knife or trowel. Riopelle’s oil-paintings are characterized by an almost sculptural surface – impasto – whereas Mitchell’s are flat and fleeting. The paintings therefore catch the light differently: Mitchell’s reflect the light very gently and suggestively; Riopelle’s shiny irregularities glitter or coruscate. The following illustration compares their surfaces, Mitchell’s is taken from an untitled 1955 painting, Riopelle’s from La Forêt ardente (1955).

Riopelle tended toward saturated primary colors, taking them straight from the tube; whereas Mitchell mixed her paints and used a much broader spectrum. The number of different shades in a Mitchell painting is generally far higher than in a Riopelle. Riopelle’s colors are much more definite; Mitchell’s tend to be lighter, sometimes fading in and out. Riopelle tended toward the red end of the spectrum, Mitchell toward the blue.

Mitchell’s paintings almost always have a white or lightly tinted background – her shapes and lines appear briefly out of the mist. Many of Riopelle’s paintings have no background, the colors intermingling without any limits. In others the background is dark, with bright colors appearing out of some primeval chaos.

Mitchell’s paintings use two main structural elements. One is the color field – an area of color that floats in the background. The second is the free line that rides above the background and the color fields. Many of her lines are made with thin paint, and leave downward-dripping rivulets of color.

Riopelle’s most famous paintings are composed like a mosaic out of brilliantly colored tesserae. In some later paintings, lines appear over the background, as though crystalizing out of the face of the deep. In other later paintings the colored regions become much larger and one can see the shapes more clearly.

Similarities

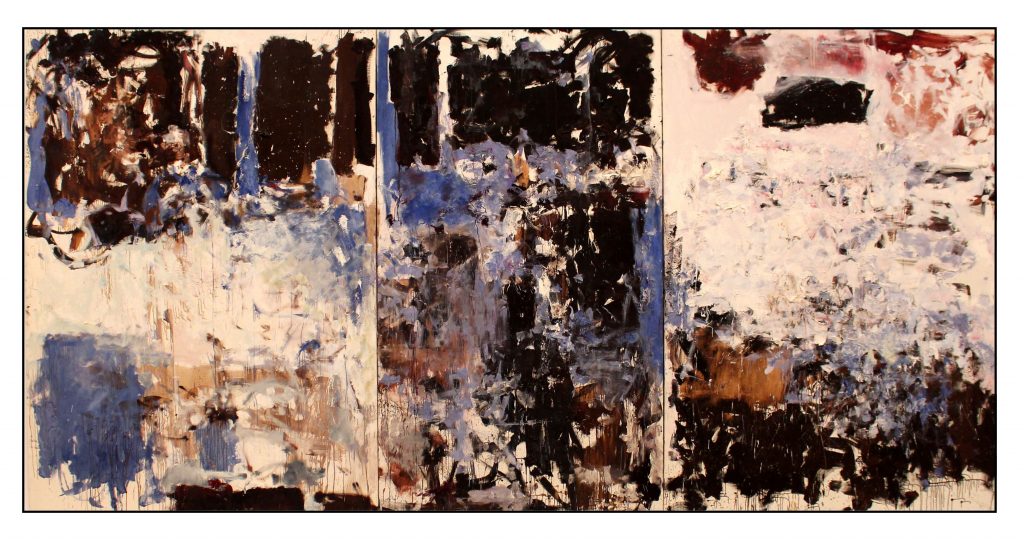

Both painters were very sensitive to symmetry. This was no mirror replication. Rather there was a balance from left to right of color, lightness and shape. Both Mitchell and Riopelle painted large diptychs and triptychs, wherein symmetry prevails. The following are two examples: Mitchell’s 1992 untitled painting (finished just before her death) and one of Riopelle’s 1977 Iceberg series (triggered by a trip to Baffin Island in the Canadian North) entitled Le Ligne d’eau.

Both artists derived their paintings from sensory experiences. Their paintings are abstracted from but not divorced from the real world. One gets a sense of the Vétheuil garden from the Mitchell’s 1992 painting, and of Baffin Island from Riopelle’s.

Sometimes the artists appear to be imitating each other styles. The exhibit pairs two untitled paintings to illustrate this. The Mitchell is from 1957 and the Riopelle from 1958; Riopelle is clearly trying out his companion’s style.

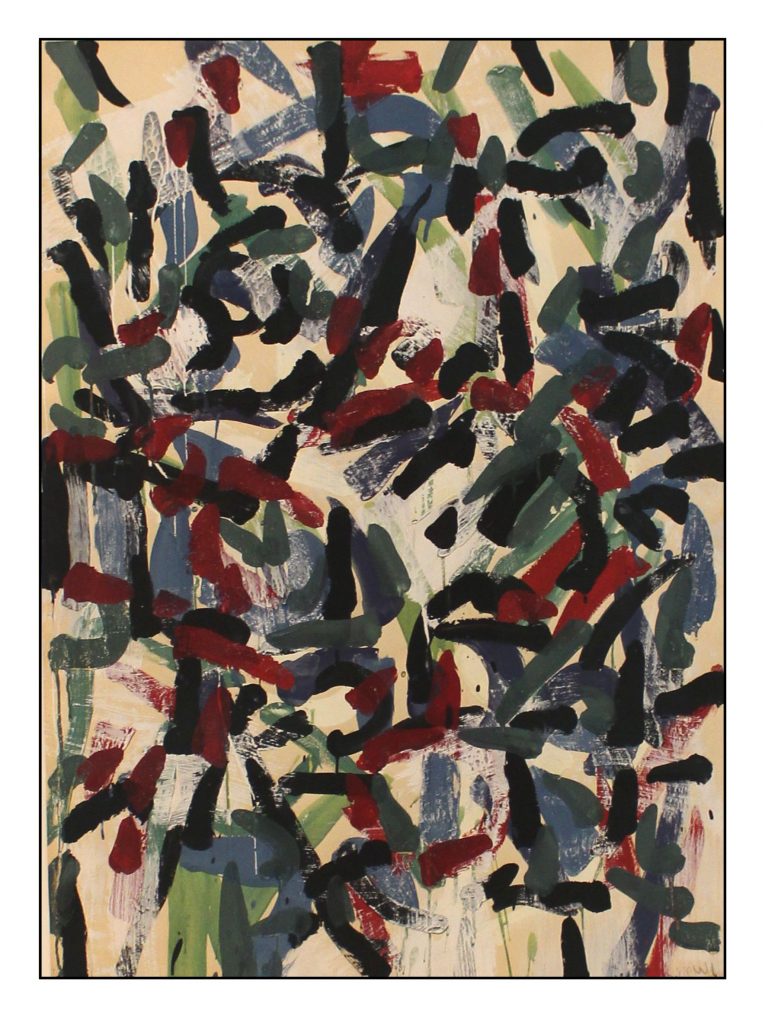

The sharing between the two artists is perhaps more evident in Riopelle’s work. His gouaches, such as the untitled 1956 example on the right, and his lithographs are composed of lines rather than shapes and have a light rather than a dark background. Nevertheless they are still in his style. His lines are short and replicate themselves. They are not Mitchell’s long, independent and free-floating lines.

The sharing between the two artists is perhaps more evident in Riopelle’s work. His gouaches, such as the untitled 1956 example on the right, and his lithographs are composed of lines rather than shapes and have a light rather than a dark background. Nevertheless they are still in his style. His lines are short and replicate themselves. They are not Mitchell’s long, independent and free-floating lines.

Mitchell’s style was more consistent over the years. She was not as much affected by Riopelle as he by her. However, in 1963 she adopted the idea of painting triptychs from Riopelle, whose first triptych had been painted in 1953 (Brummel in Martin Brummel & Michaud, 2017, p. 74). Triptychs were used by artists in the altar-pieces of the Renaissance and the Middle Ages. Pollack and other Abstract Expressionists had used the form for abstract works. Yet Riopelle almost certainly triggered Mitchell’s first attempts in the early 1960s. Thereafter multi-panel works became a mainstay of Mitchell’s art.

Endings

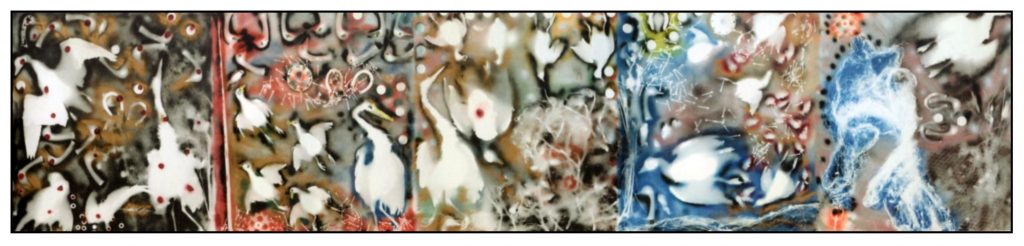

In 1992 Joan Mitchell died in Vétheuil of cancer. Jean-Paul Riopelle retreated to a studio on the Île aux Oies (Goose Island) in the Rivière Saint Laurent just north of Quebec City. Using a completely new technique – spray-cans and cut-out figures – he composed a series of images L’Hommage à Rosa Luxemburg (1992) as his memorial to Mitchell. A portion of this work, which resides permanently in the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec and is not in the AGO exhibit, is shown below.

Riopelle’s nickname for Mitchell was Rosa Malheur, a play on the name of Rosa Bonheur, a 19th century French painter. From that it was not far to Rosa Luxemburg, the Polish communist who was murdered in Germany in 1919 for promoting revolution. The painting also makes rueful reference to Mitchell’s 1979 quadriptych La Vie en Rose. Riopelle’s painting uses the bird-forms that were common in his later lithographs. These appear to signify freedom and its loss. This was Riopelle’s last painting. He died in 2002.

References

Anfam, D. (1990). Abstract Expressionism. London: Thames & Hudson.

Cogeval, G., & Aquin, S (2006). Riopelle. Montreal: Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Kertess, K. (1997). Joan Mitchell. New York: Harry N. Abrams.

Livingston, J., Mitchell, J., Nochlin, L., & Lee, Y. Y. (2002). The paintings of Joan Mitchell. New York: Whitney Museum.

Martin. M., Brummel, K., & Michaud, Y. (2017). Mitchell/Riopelle: Nothing in Moderation. Québec: Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec.

Moszynska, A. (1990). Abstract art. London: Thames and Hudson.

Pater, W. (1893, edited by Hill, D. L., 1980). The Renaissance: Studies in art and poetry Berkeley: University of California Press.

Read, H. (1931). The meaning of art. London: Faber & Faber

Sandler, I. (1970). The triumph of American painting: A history of abstract expressionism. New York: Praeger

Tucker, M., (1974). Joan Mitchell. New York: Whitney Museum of Art. Available at archive.org.

Viau, R. (2003). Jean-Paul Riopelle. Québec: Musée du Québec.