Vanity of Vanity

The words of the Preacher, the son of David, king in Jerusalem.

Vanity of vanities, saith the Preacher, vanity of vanities; all is vanity.

(Ecclesiastes 2:1-2)

Thus begins Ecclesiastes, the most unusual book in the Judeo-Christian Bible. Unlike the rest of the Bible, this book claims that the nature of the world is neither revealed to us nor accessible to reason. The universe and its Creator pay us no particular regard. Man is not special. Heretical though these thoughts might be, Ecclesiastes contains some of the world’s most widely quoted verses of scripture. The words of the Preacher resonate through the seasons of our lives. This post comments on several selections from the book.

Qohelet

The author of the book is called Qohelet (קהלת in Hebrew). This word derives from a root meaning to “assemble” or “bring people together.” The name suggests a sage who teaches a group of disciples. The translators have taken it to mean someone who preaches in a church (Latin, ecclesia). Yet Qohelet was clearly neither priest nor preacher. He was a rich man, a master of estates and an owner of palaces. The title Ecclesiastes is inappropriate. As pointed out by Lessing (1998),

thus do the living springs of knowledge, of wisdom, become captured by institutions, and by churches of various kinds.

According to the first line of the book, its author was Solomon, the son of David and Bathsheba. However, although Qohelet may have been a descendant of David, linguistic evidence (reviewed in Bundvad, 2015, pp 5-9) indicates that he wrote in the 3rd century BCE during the Hellenistic period (323-63 BCE), some seven hundred years after Solomon. Other scholars have suggested that the author may have written several centuries earlier during the Persian period (539-323 BCE), but this would still be long after Solomon (10th Century BCE).

The first line of the book may have been added by a later editor who wished this scripture to partake of Solomon’s fame. More likely, it is original, indicating that Ecclesiastes is a fictional testament: an imagined description of what Solomon might have thought (see discussion in Batholomew, 2009, pp 43-54). However, the book is ambiguous in terms of its narration. As the book progresses Qohelet becomes clearly distinguished from Solomon. And even Qohelet vacillates between two minds: that of a Jewish believer and that of a Greek philosopher (Bartholomew, 2009, p. 78).

Ben Shahn (1971) imagines Qohelet as a simple teacher. Though once rich and powerful, his thoughts have led him to withdraw from high society. Although dismayed that he has not been able to understand its meaning, he still enjoys the life he has been granted.

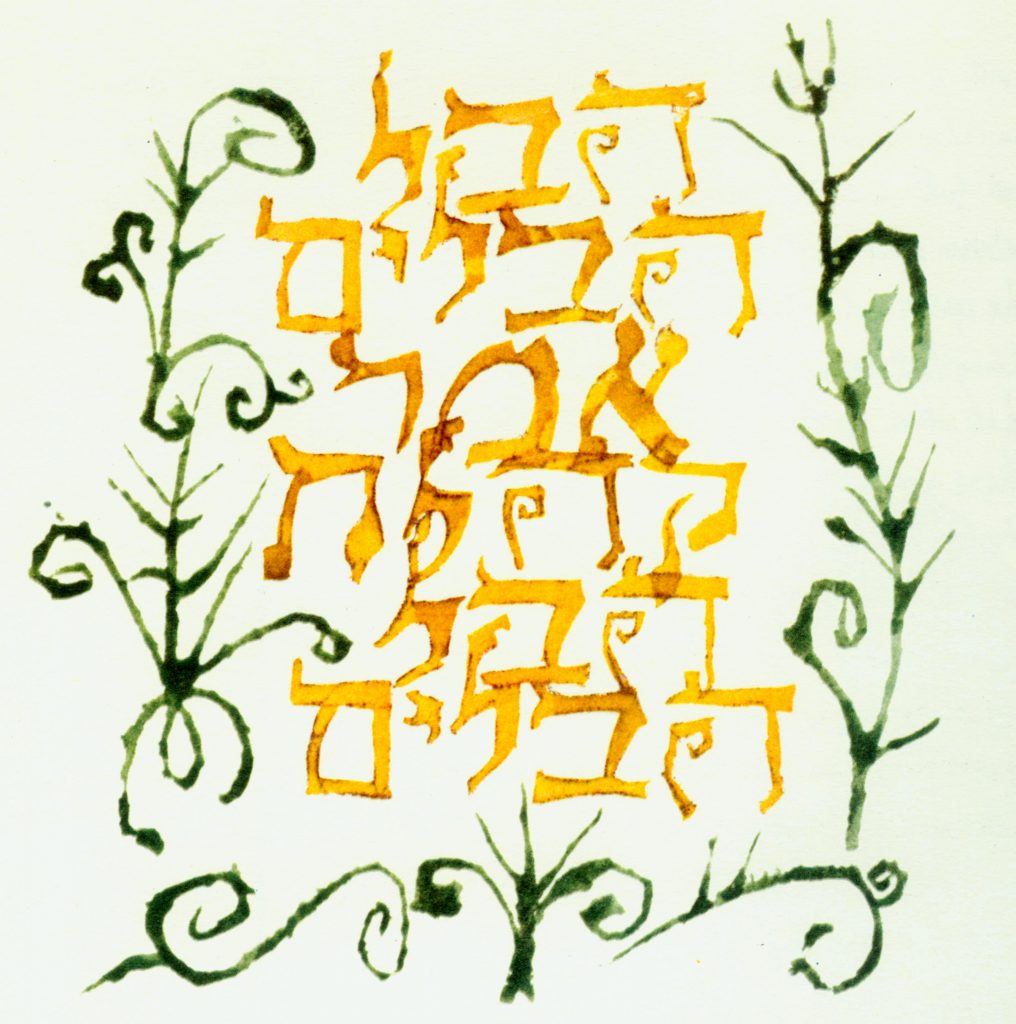

Qohelet’s summary of his philosophy is that “All is vanity.” Shahn (1971) presents the beginning of the second verse in calligraphy:

The full verse and its transliteration follows. Note that the Hebrew goes from right to left whereas the transliteration goes from left to right (As Qohelet later says, “The wind goeth toward the south and turneth about unto the north”):

הבל הבלים אמר קהלת הבל הבלים הכל הבל׃

havel havalim amar kohelet, havel havalim hakkol havel.

The sound of the Hebrew follows (just in case you wish to denounce the world’s latest frivolity out loud):

The key Hebrew word is havel (הבל). This

indicates the flimsy vapor that is exhaled in breathing, invisible except on a cold winter day and in any case immediately dissipating in the air (Alter, 2010, p 340)

The word can be directly translated as “vapor” or “breath.” Alter translates havel havelim as “mere breath.” It denotes something without material substance or temporal persistence. Many translators have characterized it in abstract terms: meaningless, transient, empty, useless, absurd, futile, enigmatic, illusory.

The word havel has the same letters as the name of Abel, the second son of Adam, slain by his brother Cain. Qohelet was likely aware of this association (Bundvad, 2015, pp 79-80). Abel was the first man to die. His life was fleeting and uncertain, his death unjust, his person only faintly remembered.

The King James Version of the Bible (1611) translates havel as “vanity.” This word comes from the Latin vanus meaning empty. The translators used “vanity” to denote a lack of meaning, value or purpose. The secondary, now more common, meaning for the word – self-admiration, excessive pride (the opposite of humility) – may have come about as a particular example of worthless activity.

At the time of the King James Version, the term vanitas was also used to denote a type of painting became popular in Flanders and the Netherlands in the 16th and 17th centuries. The example below is by Pieter Claesz (1628). These paintings arrange objects to show the transience of life, the limits of understanding and the inevitability of death. Despite their meaning, the paintings are imbued with sensual beauty:

The appeal of the vanitas painting tradition lies in its successful capture of the subtle balance between transient and joyful modes of living, so vociferously endorsed by Qoheleth. (Christianson, 2007, p 122).

Benefit

After introducing himself and summarizing his message, Qohelet poses the main question of the book:

What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun? (Ecclesiastes, 1:3)

The word translated as “profit” is yitron (יתרון). This word is only found in the Bible in Ecclesiastes. Perhaps “benefit” might be a better translation (Bartholomew, 2009, pp 107-108). The “labour” involves both physical and mental work. The idea is how best we should lead our lives.

The answer begins with the glorious poem

One generation passeth away,

and another generation cometh:

but the earth abideth for ever.

The sun also ariseth, and the sun goeth down,

and hasteth to his place where he arose.

The wind goeth toward the south,

and turneth about unto the north;

it whirleth about continually,

and the wind returneth again

according to his circuits.

All the rivers run into the sea; yet the sea is not full;

unto the place from whence the rivers come,

thither they return again.

All things are full of labour; man cannot utter it:

the eye is not satisfied with seeing,

nor the ear filled with hearing.

The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be;

and that which is done is that which shall be done:

and there is no new thing under the sun.

(Ecclesiastes 1: 3-9).

The poetry is beautiful but there is no profit in it. Human beings come and go. The human mind cannot gain sufficient knowledge of the world to understand its workings or to change it in any significant way. The world is as frustrating as it is beautiful. The more one knows, the more one is convinced of one’s transience:

For in much wisdom is much grief: and he that increaseth knowledge increaseth sorrow. (Ecclesiastes 1: 18)

Qohelet realizes that life can nevertheless be enjoyable.

There is nothing better for a man, than that he should eat and drink, and that he should make his soul enjoy good in his labour. This also I saw, that it was from the hand of God. (Ecclesiastes 2: 24)

This is the old man’s version of the Andrew Marvel’s “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.” The sentiment is perhaps as old as poetry. The Roman poet Catullus in the 1st Century BCE also wrote how the sun arises after it goes down but man does not:

soles occidere et redire possunt;

nobis, cum semel occidit brevis lux

nox est perpetua una dormienda.

da mi basia mille, deinde centum

Walter Raleigh in his History of the World (1614) translated this as

The Sunne may set and rise

But we contrariwise

Sleepe after our short light

One everlasting night.

Raleigh does not translate the continuation of the poem wherein Catullus goes on to request a compensatory thousand kisses from his lover Lesbia.

Time

Qohelet has been considering the passage of time. The word used for time in Ecclesiastes – eth (עת) – generally refers to a moment of time. The other Hebrew word for time is olam (עולם) which takes all of time into account and is usually translated as “for ever” (as in Ecclesiastes 1:4). In the first chapter Qohelet contrasted world time with human time.

In Chapter 3, he considers a different aspect of time. God has ensured that events occur at their appropriate time. Eternity has been arranged in its proper sequence.

To every thing there is a season,

and a time to every purpose under the heaven:

A time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to pluck up

that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up;

A time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones,

and a time to gather stones together;

a time to embrace,

and a time to refrain from embracing;

A time to get, and a time to lose;

a time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew;

a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate;

a time of war, and a time of peace.

(Ecclesiastes 3:1-8)

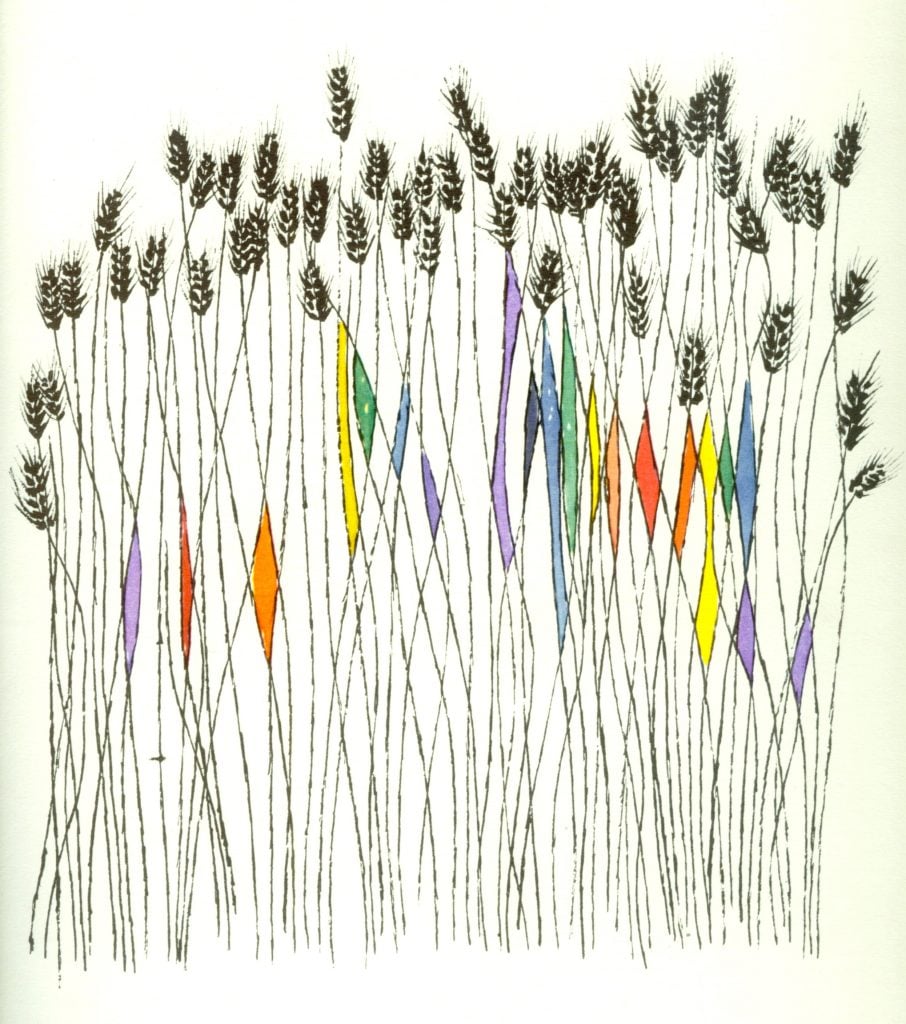

Ben Shahn (1971) portrays the essence of these lines with a wheat field at harvest time:

These verses can be interpreted in two main ways. The first proposes that time has been pre-ordained to work out the purposes of God, that we cannot change these things, and that we should be resigned to what happens. Everything is for the best. The other interpretation uses these words to justify one’s actions. Martin Luther quoted these verses when the time had come to speak out against the Catholic Church (Christianson, 2007, p 166). Thus are human actions divinely justified. Luther believed in predestination. He spoke out not by choice but because he had no choice: he could not do otherwise.

These verses were set to music by the folksinger Pete Seeger in the late 1950s. His lyrics directly quote the King James Version using the first verse with the addition of “Turn! Turn! Turn!” as the refrain. After “a time of peace” Seeger added “I swear it’s not too late.” The song became an anthem of the peace movement. The following is an excerpt:

Qohelet recognizes the beauty of God’s time. Yet he is frustrated that he can never understand it:

I know that, whatsoever God doeth, it shall be for ever: nothing can be put to it, nor any thing taken from it: and God doeth it, that men should fear before him.

That which hath been is now; and that which is to be hath already been; and God requireth that which is past.

(Ecclesiastes 3: 14-15)

This idea of time as divinely ordered but incomprehensible to the human mind pervades T. S. Eliots’ Burnt Norton (1935) which begins:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future,

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

What might have been is an abstraction

Remaining a perpetual possibility

Only in a world of speculation.

What might have been and what has been

Point to one end, which is always present.

Qohelet goes on to state that since we cannot understand we are no different from other animals. We live, we die.

For that which befalleth the sons of men befalleth beasts; even one thing befalleth them: as the one dieth, so dieth the other; yea, they have all one breath; so that a man hath no preeminence above a beast: for all is vanity.

All go unto one place; all are of the dust, and all turn to dust again.

(Ecclesiastes 3:19-20)

These statements go against all previous Jewish teachings. Qohelet’s book

amounts to a denial of divine revelation, and of the belief that man was created as an almost divine being, to care for and exercise dominion over the other creatures and all the works of God’s hands. … In the final analysis man is like the animals rather than superior to them (Scott, 1965, p. 205)

Johannes Brahms was devastated when his friend Clara Schumann suffered a stroke in 1895 and was close to death. During this time, he composed his Four Serious Songs Opus 121. The first song is uses Luther’s translation of Ecclesiastes 3: 19-22. The following is the beginning (up to wird wieder zu Staub “turn to dust again”) as sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau:

Denn es gehet dem Menschen wie dem Vieh; wie dies stirbt, so stirbt er auch; und haben alle einerlei Odem;und der Mensch hat nichts mehr denn das Vieh: denn es ist alles eitel.

Es fährt alles an einen Ort; es ist alles von Staub gemacht, und wird wieder zu Staub.

This first song is desolate – we die like beasts, our life is empty, we are made of dust. The later songs in the series progress from deep sadness to quiet resignation. The final song sets verses from the New Testament, among them

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. (I Corinthians 13:12)

Brahms called his songs “serious” (ernst) rather than “sacred.” This is a fitting description of the book Ecclesiastes.

Justice

After considering the inevitability of death, Qohelet turns to evaluate the course of human life. He finds that success does not necessarily reward those who most deserve it:

I returned, and saw under the sun, that the race is not to the swift, nor the battle to the strong, neither yet bread to the wise, nor yet riches to men of understanding, nor yet favour to men of skill; but time and chance happeneth to them all.

(Ecclesiastes 9:11)

A brief adaptation of this verse was included in the posthumously published Last Poems of D. H. Lawrence (1932). The poem Race and Battle is notable for its image of the “streaked pansy of the heart” which recalls the title of his earlier book Pansies, itself a pun on Pascal’s Pensées. Lawrence attempts to explain how to accept that life may be unfair and preserve a personal sense of justice.

The race is not to the swift

but to those that can sit still

and let the waves go over them.

The battle is not to the strong

but to the frail, who know best

how to efface themselves

to save the streaked pansy of the heart from

being trampled to mud.

Lawrence’s poem adds to Qohelet’s resignation some of the later teachings of Jesus – Blessed are the meek: for they shall inherit the earth… Blessed are the pure in heart: for they shall see God (Matthew 5: 5,8).

Instruction

Qohelet’s search for wisdom has led him to dismay. Death is inevitable and unpredictable. Life is without justice. Nevertheless, Qohelet urges us to enjoy our life:

Go thy way, eat thy bread with joy, and drink thy wine with a merry heart; for God now accepteth thy works.

Let thy garments be always white; and let thy head lack no ointment.

Live joyfully with the wife whom thou lovest all the days of the life of thy vanity, which he hath given thee under the sun, all the days of thy vanity: for that is thy portion in this life, and in thy labour which thou takest under the sun.

Whatsoever thy hand findeth to do, do it with thy might; for there is no work, nor device, nor knowledge, nor wisdom, in the grave, whither thou goest.

(Ecclesiastes 9:7-10)

White clothes are worn for festive occasions. Their whiteness contrasts with the black of mourning. Anointing one’s hair with oil is another sign of gladness. Yet the most important of Qohelet’s injunctions is to work at whatever needs to be done.

Qohelet’s advice is related to the philosophies of Epicurus (341-270 BCE) in its enjoyment of life and of the stoic Zeno (334-262 BCE) in its promotion of right action. If, as most scholars now believe, Qohelet wrote in the 3rd Century BCE, he could have been influenced by such Greek philosophies. He certainly based his search for truth on reason rather than on revelation. Yet his philosophy is his own. It is religious rather than materialist.

Scott (1965, p 206) summarizes Qohelet’s reasoning:

Thus the good of life is in the living of it. The profit of work is in the doing of it, not in any profit or residue which a man can exhibit as his achievement or pass on to his descendants. The fruit of wisdom is not the accumulation of all knowledge and the understanding of all mysteries. It lies rather in recognizing the limitations of human knowledge and power. Man is not the measure of all things. He is the master neither of life nor of death. He can find serenity only in coming to terms with the unalterable conditions of his existence, and in enjoying its real but limited satisfactions.

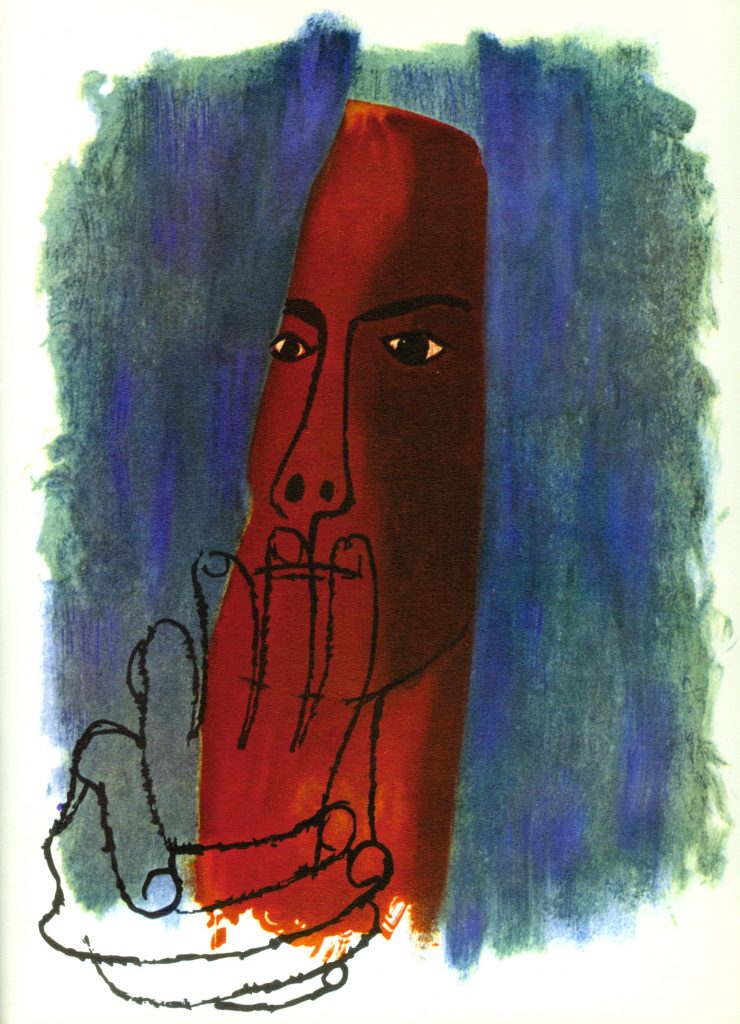

Ben Shahn presents the thoughts of Qohelet as balanced between his inability to understand and his realization that life can nevertheless be enjoyed:

Qohelet has much in common with the existentialism of the 20th Century. Albert Camus remarks in Le Mythe de Sisyphe (1942):

Je ne sais pas si ce monde a un sens qui le dépasse. Mais je sais que je ne connais pas ce sens et qu’il m’est impossible pour le moment de le connaître. [I don’t know whether this world has a meaning that transcends it. But I know that I cannot grasp that meaning and that it is impossible now for me to grasp it.]

Camus is much more tentative than Qohelet in his conclusion that we should nevertheless enjoy our life. He retells the myth of Sisyphus who was condemned by the Gods because he had tried to cheat death. He was made to roll an immense boulder up to the summit of a mountain, but every time he reached the top, the rock would roll back down and Sisyphus would have to begin his task again.

La lutte elle-même vers les sommets suffit à remplir un cœur d’homme; il faut imaginer Sisyphe heureux. [The very struggle toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy. ]

Bread upon the Waters

Qohelet presents us with multiple proverbial injunctions about how one should live one’s life. Perhaps the most quoted of these is:

Cast thy bread upon the waters: for thou shalt find it after many days.

Give a portion to seven, and also to eight; for thou knowest not what evil shall be upon the earth.

(Ecclesiastes 11: 1-2)

The verses have been interpreted in many ways. Merchants have considered them in terms of overseas trade. Christians have proposed that it means to spread the teachings of Christ throughout the world. This idea derives from Christ’s statement that he was the “bread of life” (John 6:35). Qohelet had neither of these ideas in mind. He was encouraging us to be generous, to provide for our fellows. He was suggesting that such human charity could compensate for life’s injustice.

In his own old age, the wise Richard Wilbur (2010) wrote a poem about these verses

We must cast our bread

Upon the waters, as the

Ancient preacher said,

Trusting that it may

Amply be restored to us

After many a day.

That old metaphor,

Drawn from rice farming on the

River’s flooded shore,

Helps us to believe

That it’s no great sin to give,

Hoping to receive.

Therefore I shall throw

Broken bread, this sullen day,

Out across the snow,

Betting crust and crumb

That birds will gather, and that

One more spring will come.

Light and Dark

Qohelet reminds us that life brings both enjoyment and dismay. The verses are illustrated by Ben Shahn on the left.

Truly the light is sweet, and a pleasant thing it is for the eyes to behold the sun:

But if a man live many years, and rejoice in them all; yet let him remember the days of darkness; for they shall be many.

(Ecclesiastes 11: 7-8)

Remember Now

The last chapter of Ecclesiastes contains its most famous poetry. Qohelet, who has become old and wise, advises his youthful followers. He tells them to rejoice in their youth for life is beautiful. Yet they must always bear in mind that they must grow old and die:

Remember now thy Creator in the days of thy youth,

while the evil days come not,

nor the years draw nigh, when thou shalt say,

I have no pleasure in them;

While the sun, or the light, or the moon,

or the stars, be not darkened,

nor the clouds return after the rain:

In the day when the keepers of the house shall tremble,

and the strong men shall bow themselves,

and the grinders cease because they are few,

and those that look out of the windows be darkened,

And the doors shall be shut in the streets,

when the sound of the grinding is low,

and he shall rise up at the voice of the bird,

and all the daughters of musick shall be brought low;

Also when they shall be afraid of that which is high,

and fears shall be in the way,

and the almond tree shall flourish,

and the grasshopper shall be a burden,

and desire shall fail:

because man goeth to his long home,

and the mourners go about the streets:

Or ever the silver cord be loosed,

or the golden bowl be broken,

or the pitcher be broken at the fountain,

or the wheel broken at the cistern.

Then shall the dust return to the earth as it was:

and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it.

Vanity of vanities, saith the preacher; all is vanity.

(Ecclesiastes 12: 1-8)

Qohelet refers to God as the Creator (borador, בוראיך). This is the only time he uses this term; elsewhere he uses Elohim (אלהים). Qohelet is here invoking Genesis: we must view the end of an individual life in relation to the beginning of all life. Some commentators (Rashi; Scott, 1965, p. 255) have remarked on the relations of this word to bor (בור) which occurs in the 7th verse. This means “pit,” in the sense of either a “grave” or a “cistern.” This verbal association also brings the end of life back to its source.

The poem is as enigmatic as it is beautiful. The initial verse of the poem clearly states that it is concerned with human mortality. Yet how the images relate to old age and death is as uncertain as the breath that ceases. And the poem ends on the words that began the book – all is vanity, merest breath.

A literal interpretation is that the poem describes a village or estate in mourning for a once-great person lately fallen on hard times. Perhaps Qohelet is foreseeing his own death. The windows of the house are darkened, the mill is quiet as the workers remember their late master, the mourners go about the streets, and finally dust is scattered over the body as it is buried.

A long tradition has provided allegorical interpretations of the images, relating them to the physical and mental decline that attends old age. The underlying idea is that the aging body is like a house in decay. For example, the commentary of the 11th-century Jewish rabbi Rashi suggests

the keepers of the house: These are the ribs and the flanks, which protect the entire body cavity

the mighty men: These are the legs, upon which the body supports itself

and the grinders cease: These are the teeth

since they have become few: In old age, most of his teeth fall out

and those who look out of the windows: These are the eyes.

And the doors shall be shut: These are his orifices.

when the sound of the mill is low: the sound of the mill grinding the food in his intestines, and that is the stomach

The problem with such specific allegories is that different commentators provide different meanings. Do the doors that shut denote the eyelids or the lips?

Other interpretations are more abstract. Does the pitcher broken at the fountain represent the bladder or the loss of the life force? Is the silver cord the spinal column or the genealogical tree that ends at the death of a person with no heirs?

Some Hebrew interpretations consider these verses as representing the desolation of Israel following the destruction of the First Temple by the Babylonians in 587 BCE. The image of the golden bowl might then represent the broken lamp that no longer lit the sanctuary.

Some Christian interpretations see the imagery as a vision of the end times that will precede the final judgment. This fits with the epilogue that follows the poem.

No single interpretation conveys the sense of the poem. All meanings overlap. The poem is better listened to than imagined. The following is by the YouTube reader who goes by the name of Tom O’Bedlam

Judgment

The book concludes with an epilogue that many take to be the words of a later editor. However, it rings true to Qohelet:

Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God, and keep his commandments: for this is the whole duty of man.

For God shall bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it be evil.

(Ecclesiastes 12: 13-14)

Why else should one remember one’s Creator? Why else should one bear in mind one’s ultimate old age and death? The sentiment is similar to Marcus Aurelius (167 CE):

Do not act as if thou wert going to live ten thousand years. Death hangs over thee. While thou livest, while it is in thy power, be good.

(Meditations IV:17)

Qohelet is also proposing that to be good is to be truly human – “the whole duty of man.” Any judgment of us as human beings must rest on whether we have done good or ill. Qohelet’s instruction derives from man as much as from God.

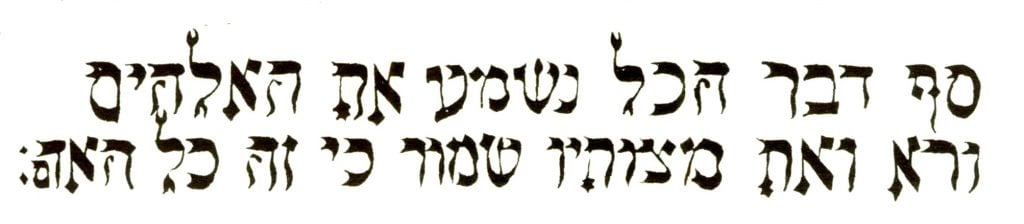

The following presents the Hebrew (in Ben Shahn’s calligraphy) together with its transliteration and an audio version of Ecclesiastes 12:13

Let us hear the conclusion of the whole matter: Fear God, and keep his commandments: for this is the whole duty of man.

sovf dabar hakkol nishma eth ha’elohim yera eth mitzvotav shemovr ki zeh kol ha’adam.

References

Alter, R. (2010). The wisdom books: Job, Proverbs, and Ecclesiastes : a translation with commentary. New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

Bartholomew, C. G. (2009). Ecclesiastes. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic.

Bundvad, M. (2015). Time in the book of Ecclesiastes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Christianson, E. S. (2007). Ecclesiastes through the centuries. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Lawrence, D. H. (Edited by Aldington, R., & Orioli, G., 1932). Last poems. Florence: Orioli.

Lessing, D. (1998). Introduction. In Ecclesiastes or, the preacher: Authorised King James version. Edinburgh: Canongate.

Scott, R. B. Y. (1965). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes. (Anchor Bible Volume 18). Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

Shahn, B. (1971). Ecclesiastes: Or, the preacher. New York: Grossman.

Wilbur, R. (2010). Anterooms: New poems and translations. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.