Edward Hopper

Edward Hopper (1882-1967) painted the independence and the loneliness of 20th-Century America. He was a realist in the days when most painters tended toward the abstract. Yet his paintings incite the imagination far more than the works of any abstract expressionist. His enigmatic images force the viewer to wonder what is going on:

Hopper was neither an illustrator nor a narrative painter. His paintings don’t tell stories. What they do is suggest—powerfully, irresistibly—that there are stories within them, waiting to be told. He shows us a moment in time, arrayed on a canvas; there’s clearly a past and a future, but it’s our task to find it for ourselves. (Block, 2016, p viii).

More than any other painter, Hopper has inspired writers to find the stories and meanings behind his paintings. This post summarizes his life, describes his working methods, and presents some of his pictures together with the writings they have stimulated.

Early Life

Hopper was born in Nyack, a town on the Hudson River some 25 km north of the upper end of Manhattan (Levin, 1980a, 2007). He decided early to become an artist and studied at the New York School of Art and Design in Greenwich Village, where he was taught by William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, among others. Hopper considered Thomas Eakins his artistic hero.

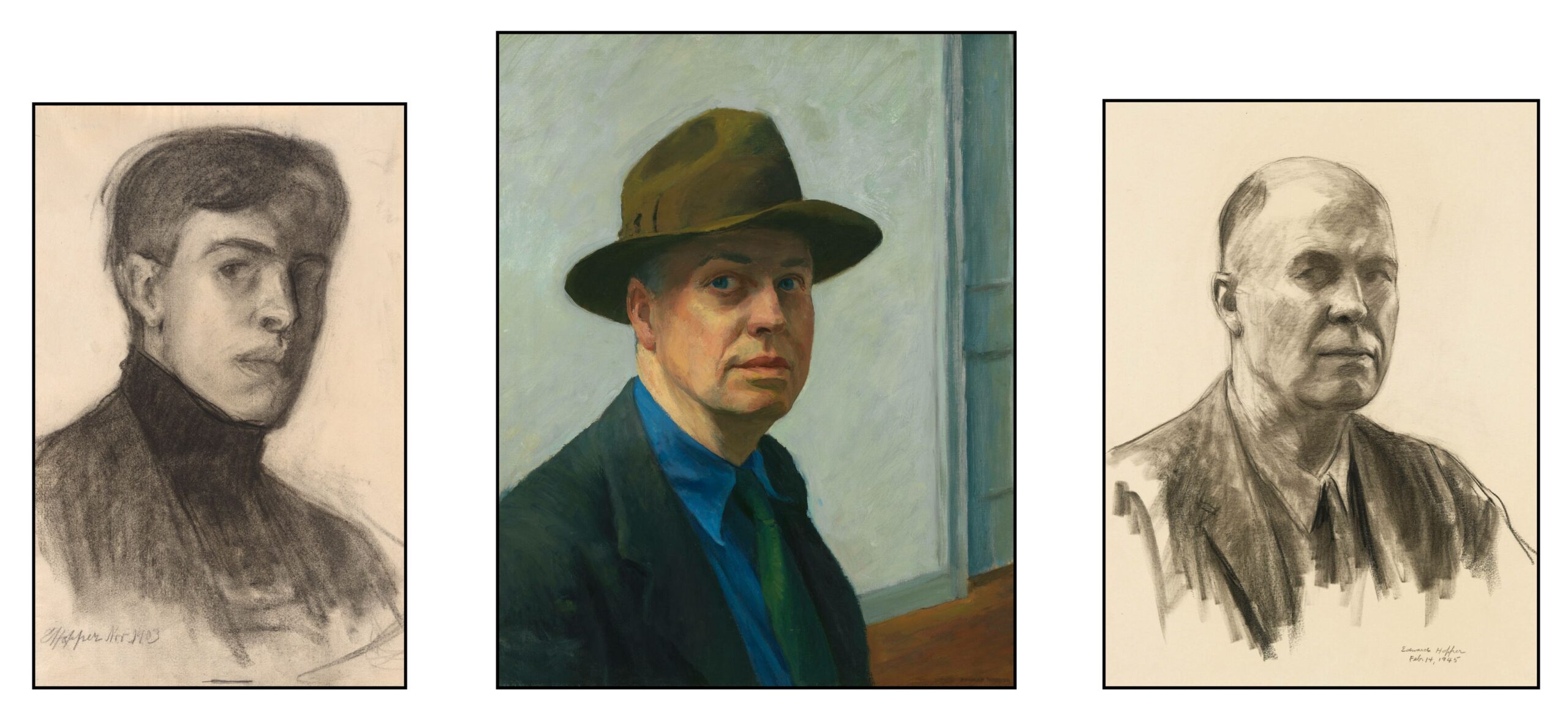

The 1903 self-portrait, illustrated on the left below, shows the conscientious young student. The others are from 1930, when he was becoming successful, and from 1945 after he had become famous.

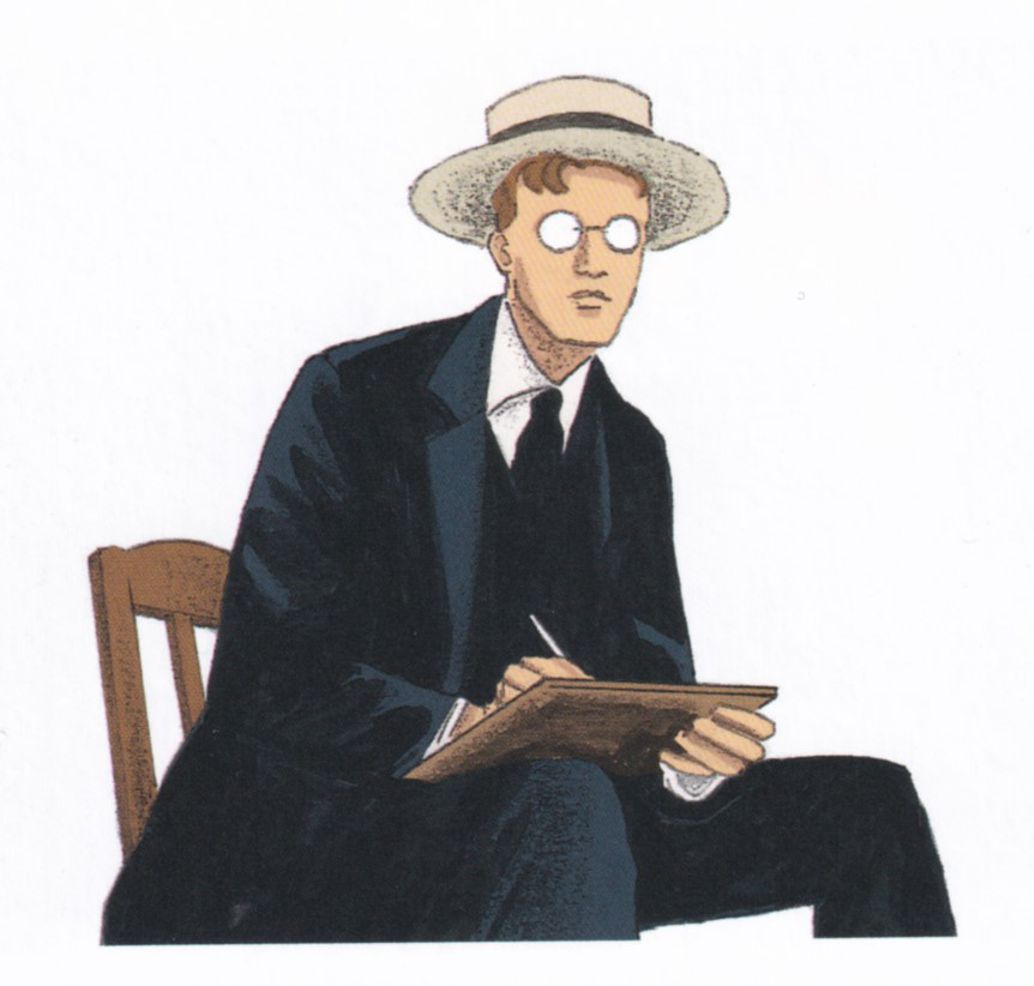

In 1906 Hopper made his first trip to Paris, where he stayed for almost one year, making occasional journeys to other cities in Europe. He returned for two further shorter visits in 1909 and 1910. In Paris, he visited the museums, attended classes, and sketched and painted en plain air. The illustration on the right from the graphic biography by Rossi and Scarduelli (2021) was derived from a 1907 photograph of the young student sketching (Levin, 2007, p 68).

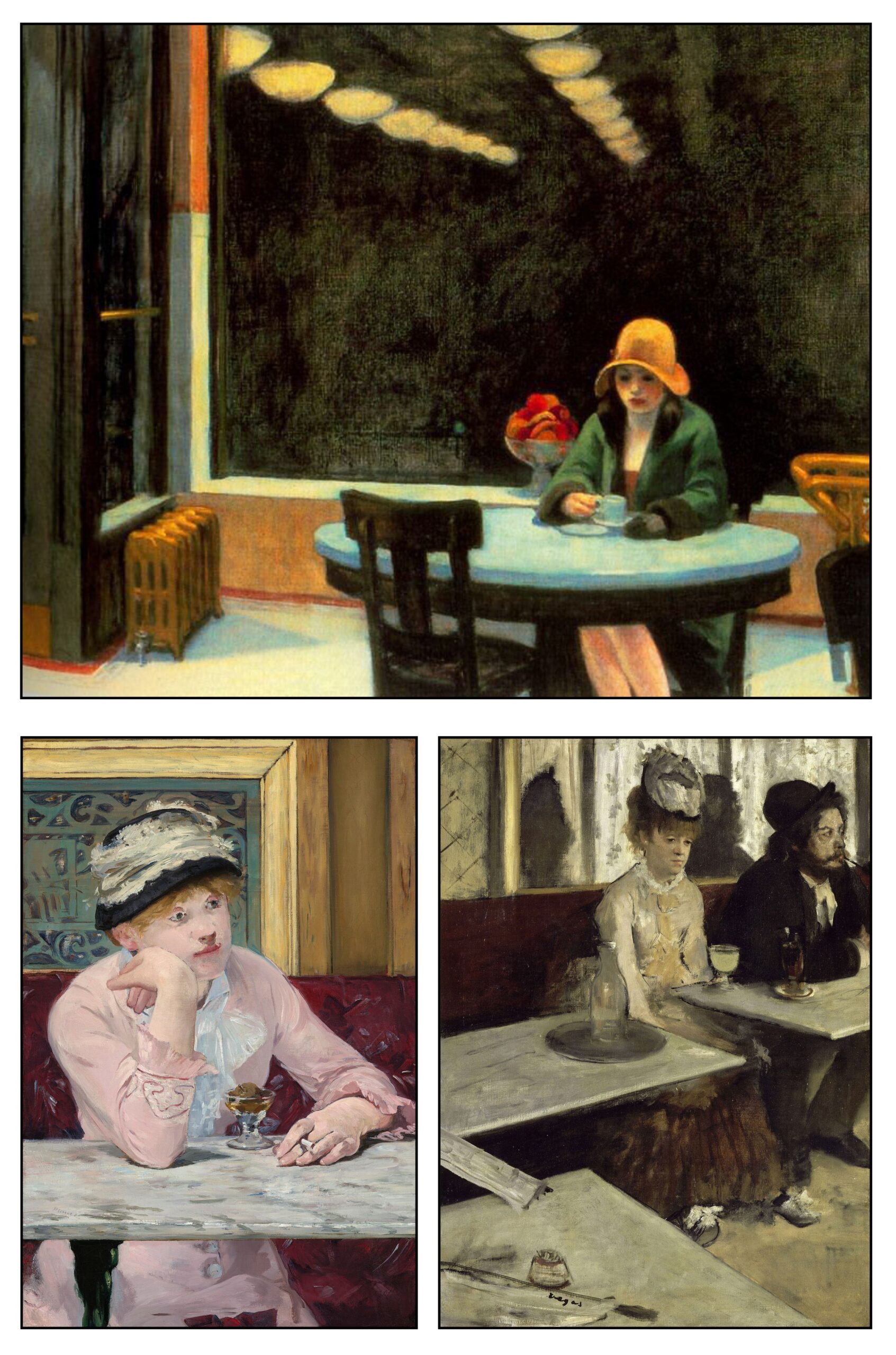

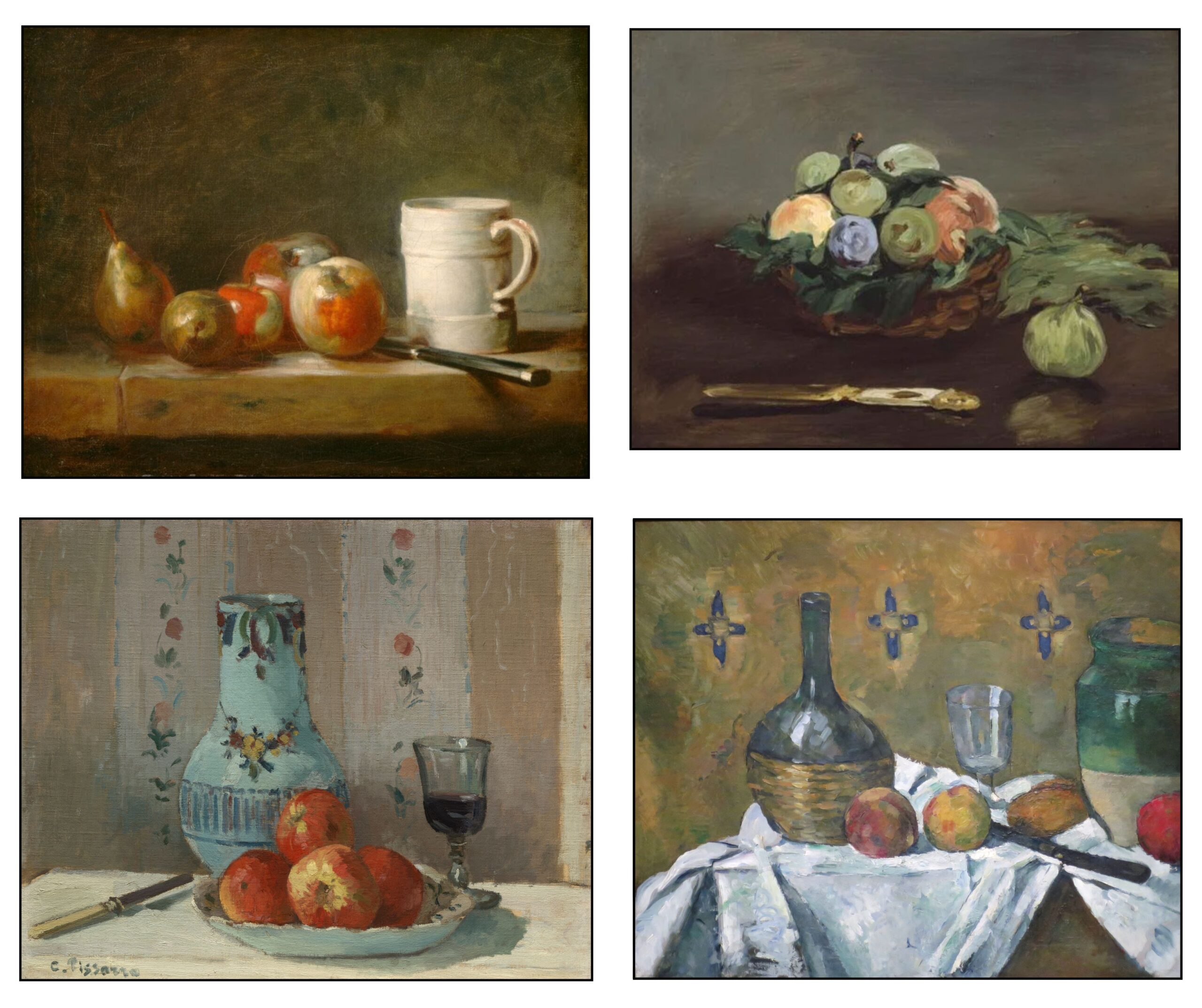

Hopper was influenced by the impressionists, in particular Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas (Kranzfelder, 2002, p 150). His later painting Automat (1927) shows similarities in mood and structure to Manet’s The Plum Brandy (1877) and to Degas’ The Absinthe Drinker (1876):

Another influence was Eugéne Atget who had photographed the empty streets of Paris (Llorens & Ottinger, 2012, p. 263). Since his camera required long exposure-times, Atget chose to photograph early in the morning before there were any people moving around in the streets. His haunting images foreshadow Hopper’s lonely city-scenes. Walter Benjamin in his Little History of Photography (1931) remarked that Atget’s photographs sometimes seem to portray the “scene of a crime.” The same can be said of many of Hopper’s paintings.

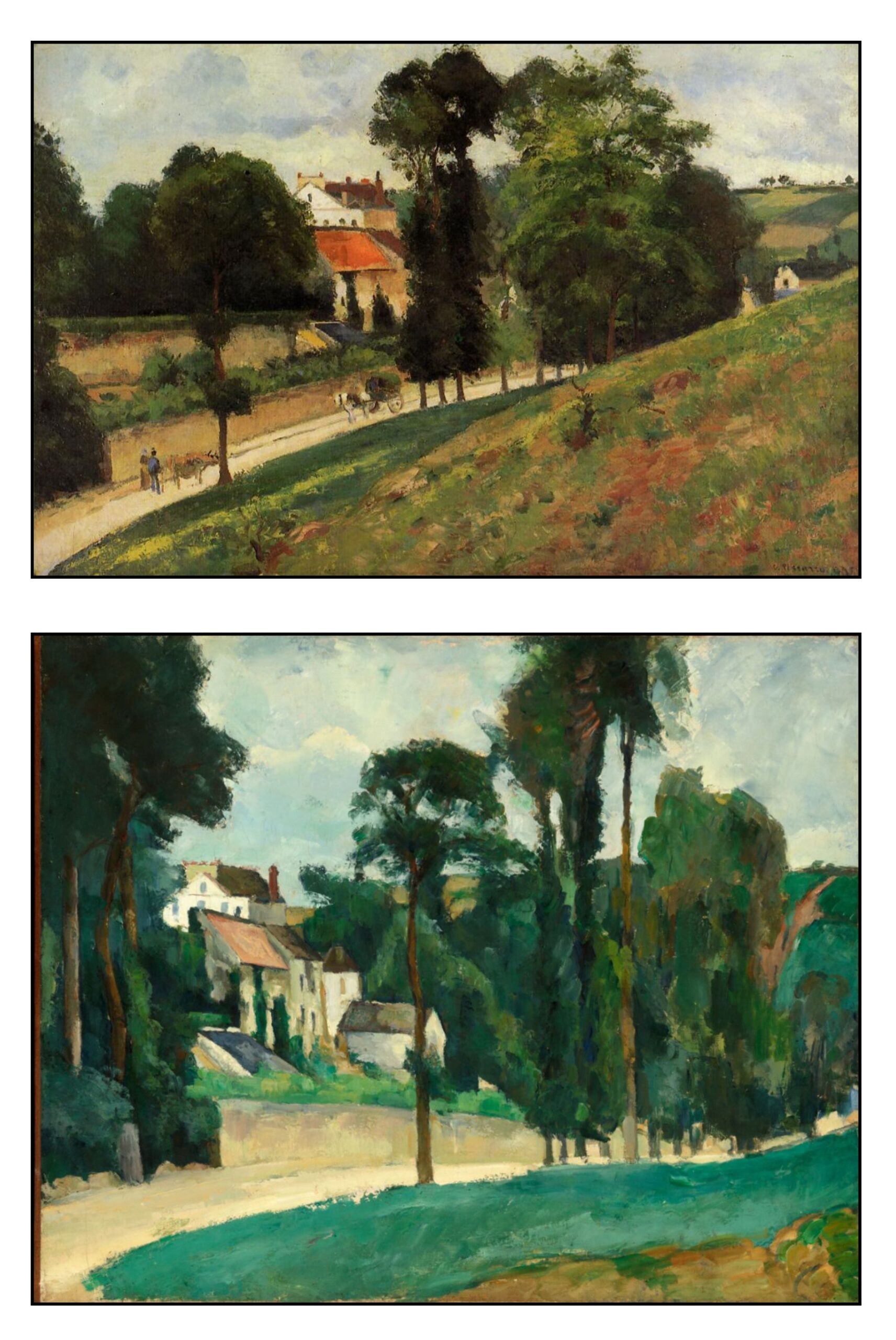

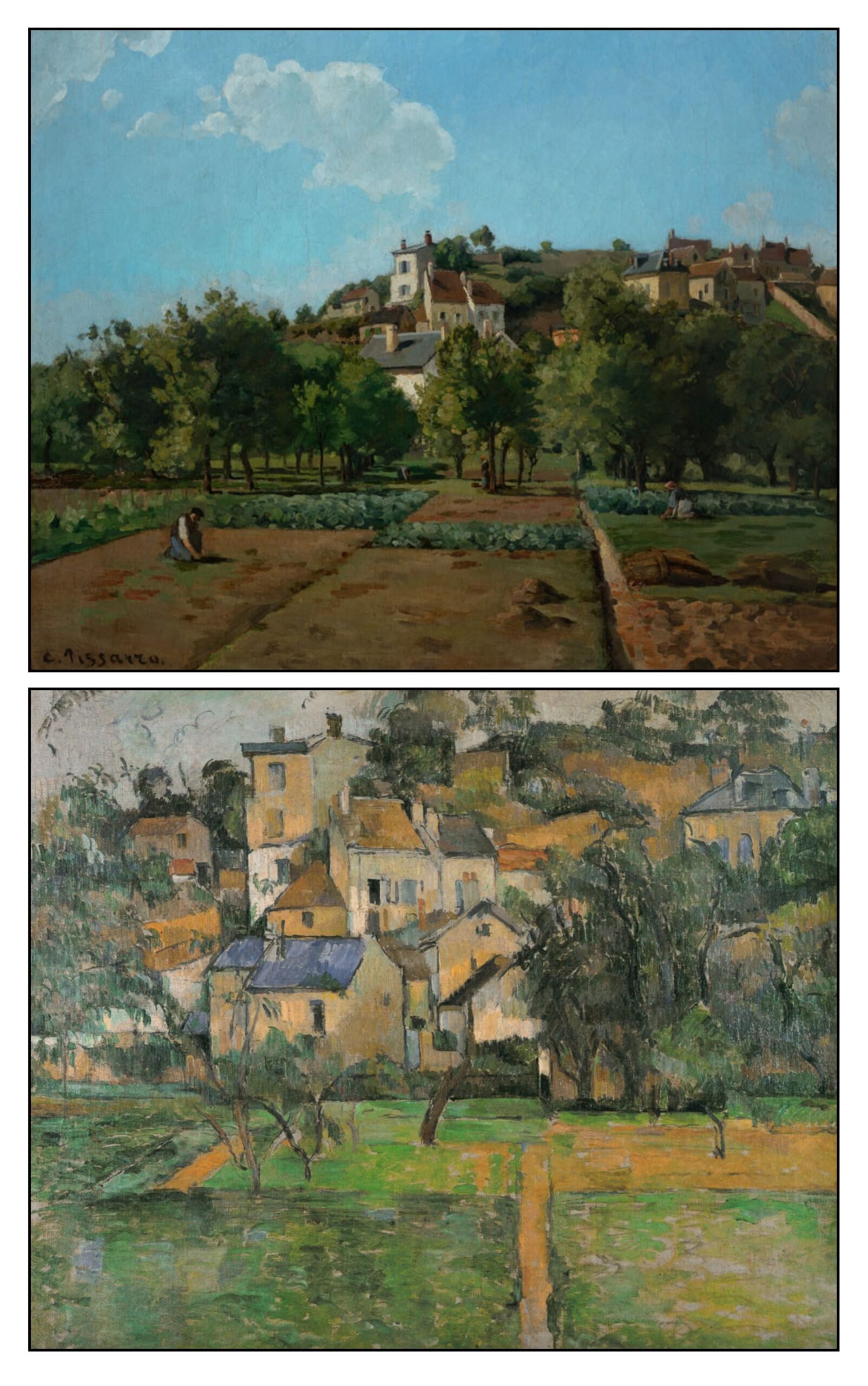

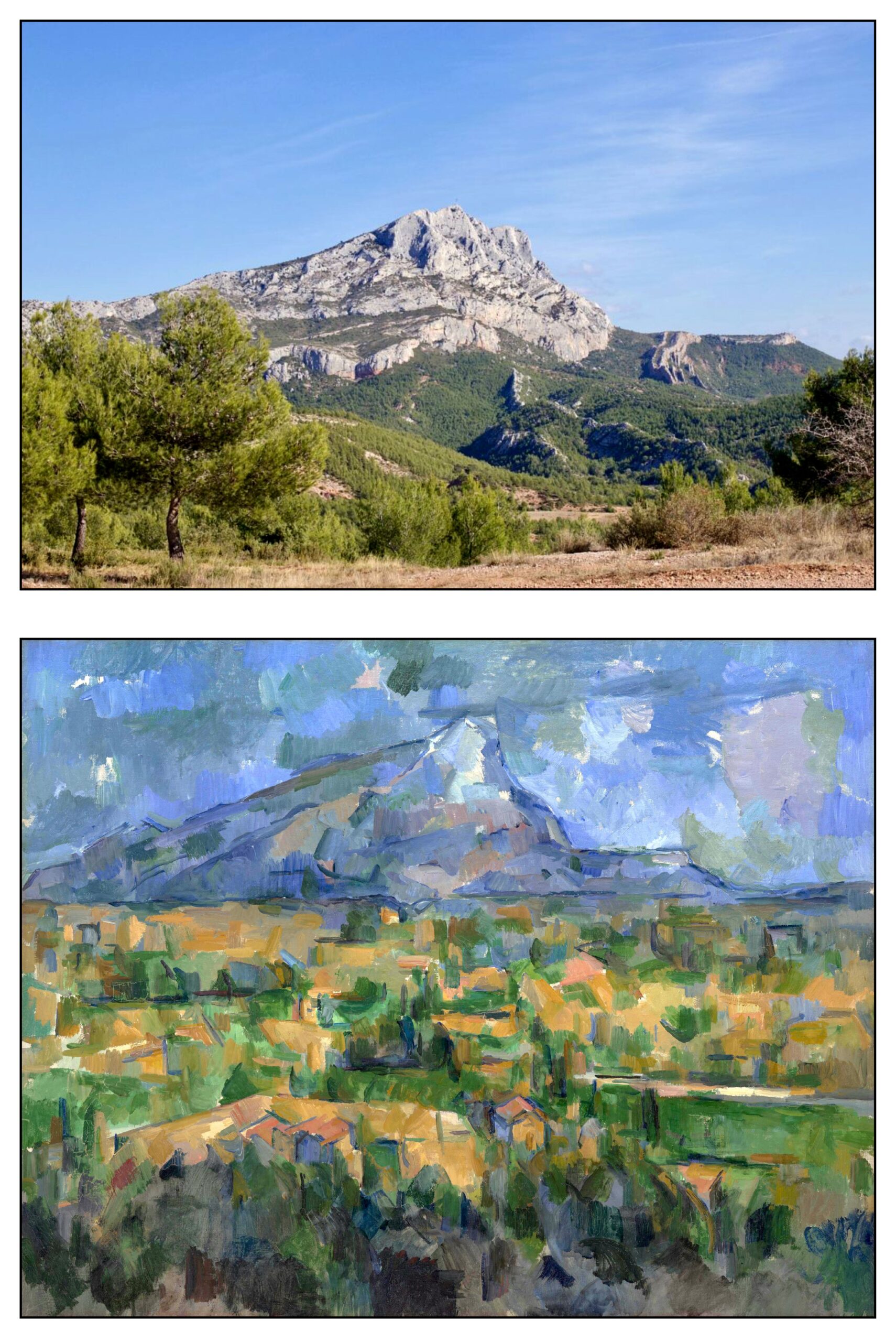

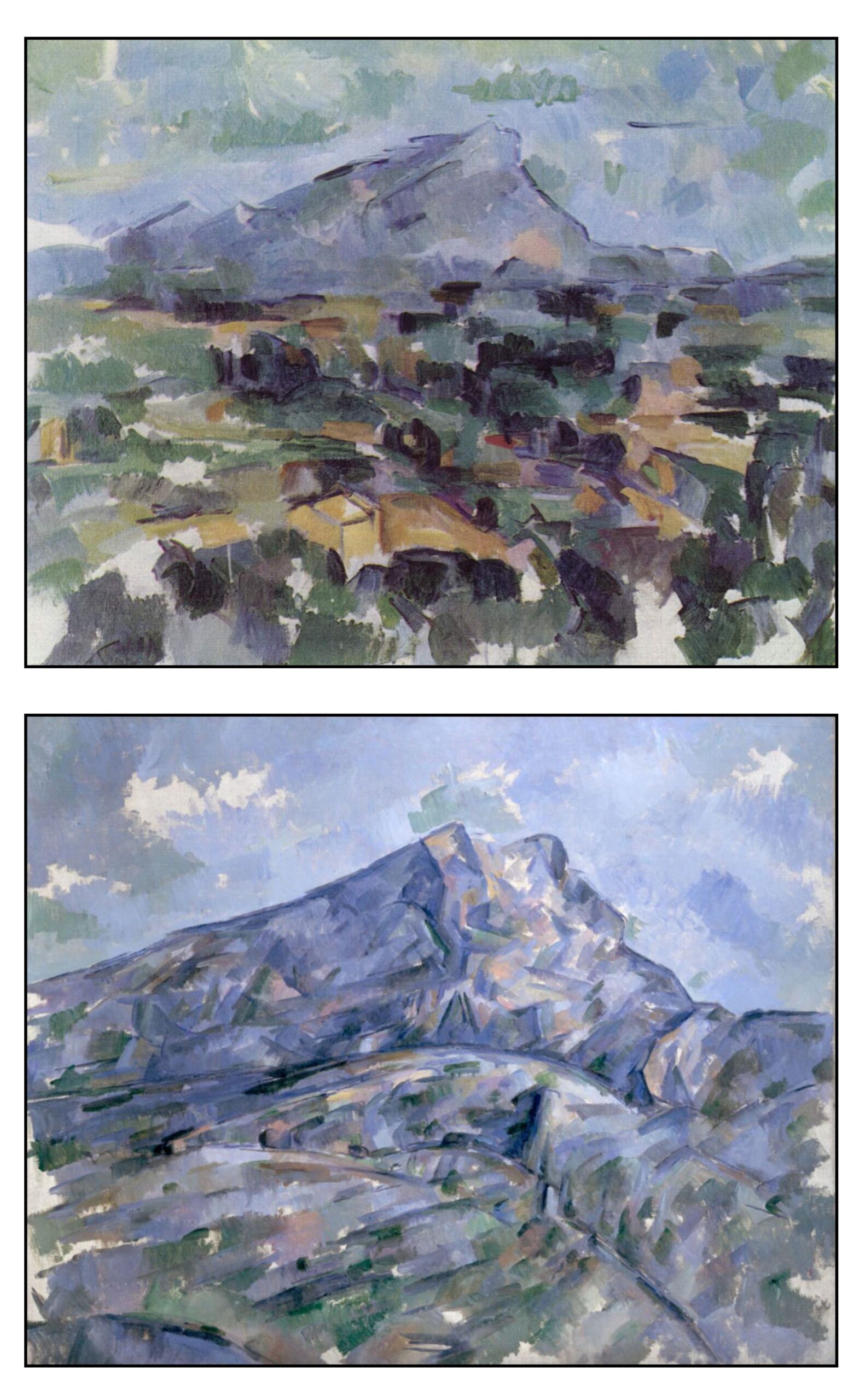

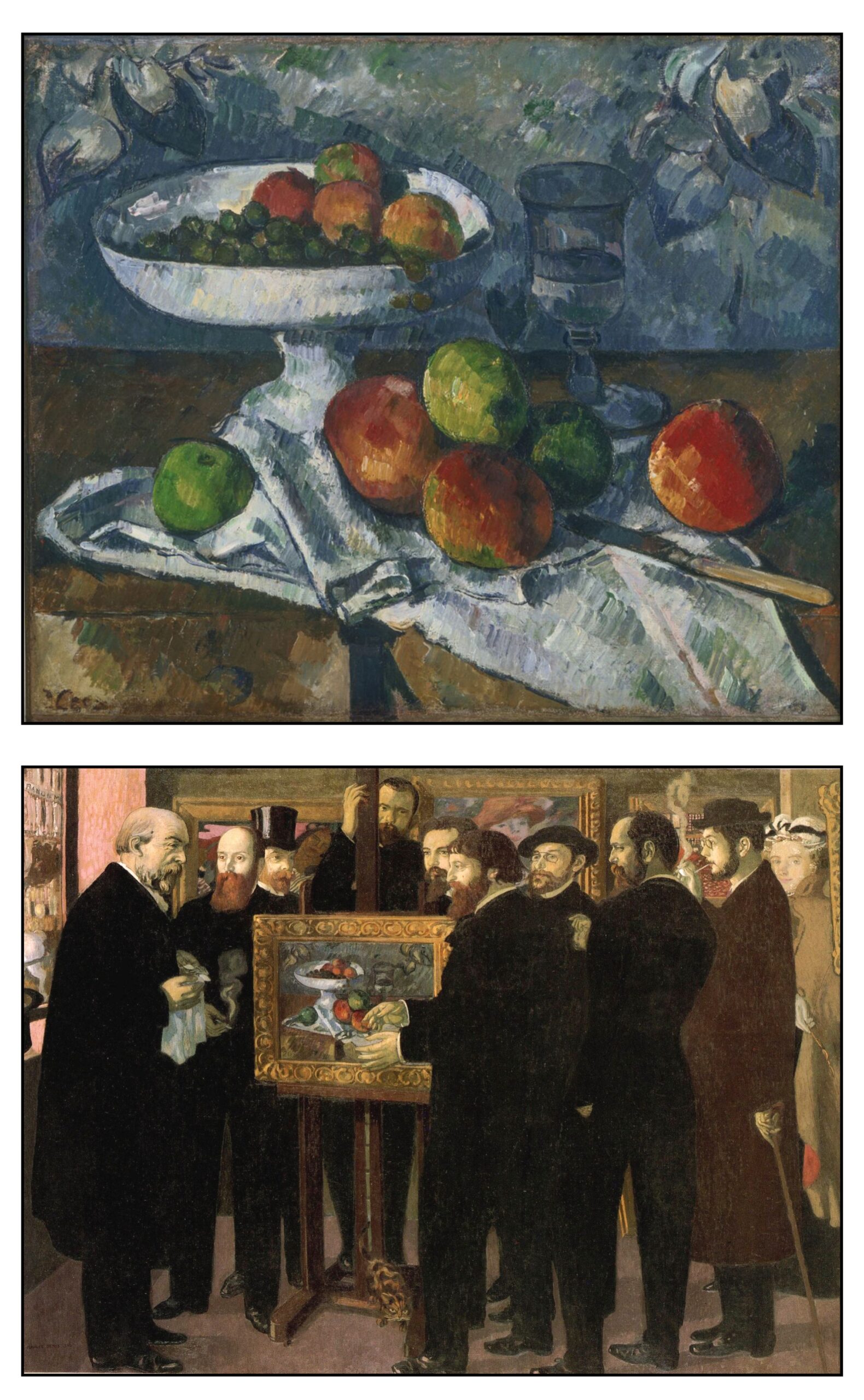

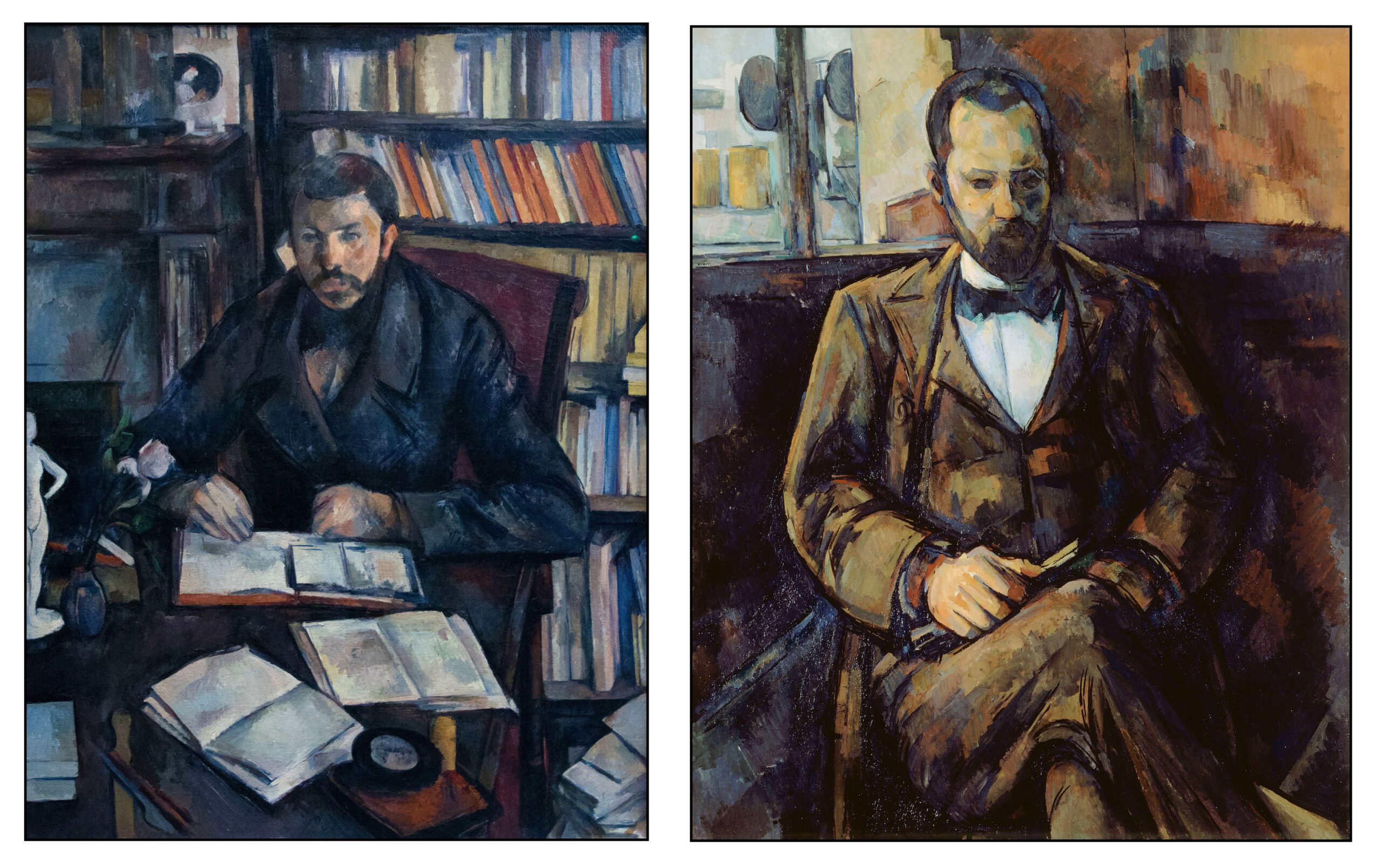

The ongoing modernist revolution in Paris had no effect on the young American. Hopper paid little attention to the post-impressionists (Van Gogh, Cézanne and Gauguin), and was apparently unaware of the current work of painters like Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

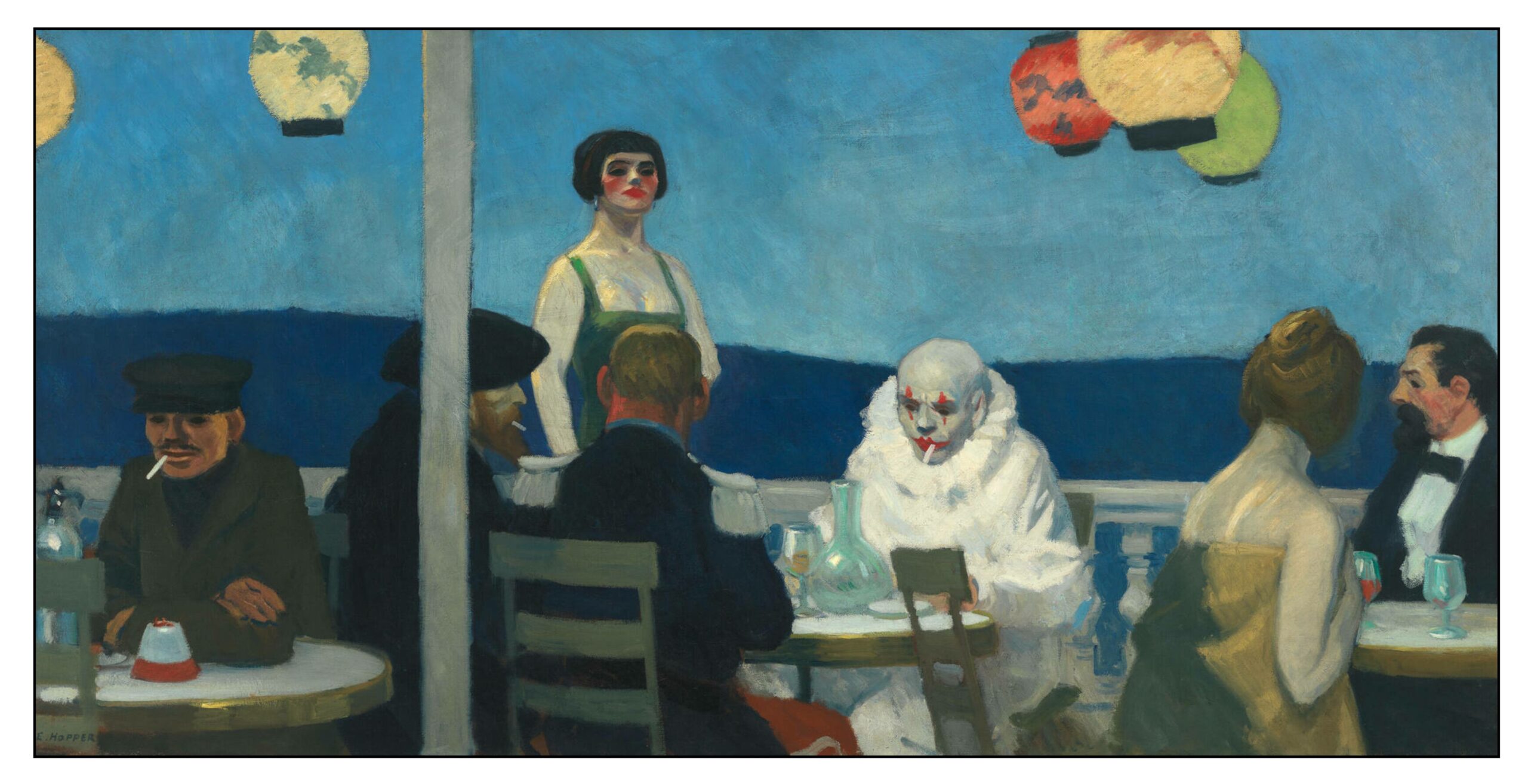

One of the last paintings from Hopper’s time in Europe was entitled Soir Bleu (1914). Various characters interact on a café terrace:

On the left is a macquereau (French: mackerel, slang for “pimp”). In the center, a garishly made-up prostitute attempts to entice a client from a table where three men are seated: someone who appears from his beret to be an artist, a soldier with epaulettes on his uniform, and a clown in full make-up and costume. On the right a bourgeois man and woman survey the scene. One is tempted to consider Hopper as the clown, out of place and without voice among the French. Three of the figures are smoking: the clown, the pimp and the artist. This may suggest something similar in their livelihoods: they all survive by selling to the rich and powerful: the couple on the right and the soldier. Hopper exhibited the painting when he returned to New York, but it was never sold and stayed in storage at his studio until his death.

The painting’s title may come from a poem Sensation (1870) by Rimbaud, which in its second verse talks of being mute like the clown.

Par les soirs bleus d’été j’irai dans les sentiers,

Picoté par les blés, fouler l’herbe menue :

Rêveur, j’en sentirai la fraicheur à mes pieds.

Je laisserai le vent baigner ma tête nue.

Je ne parlerai pas ; je ne penserai rien.

Mais l’amour infini me montera dans l’âme ;

Et j’irai loin, bien loin, comme un bohémien,

Par la Nature,—heureux comme avec une femme.

Summer’s deep-blue evenings I will go down the lanes,

Tickled by the wheat-berries, trampling the short grass:

Dreaming, I will feel the coolness at my feet.

I will let a northern wind bathe my bare head.

I will not stir my tongue; I will think of nothing.

Yet love infinite shall at once mount in my soul;

And I will go far, very far, like a gypsy,

Through Nature,—enchanted as with a woman.

(translation by Gregory Campeau)

Back in New York, Hopper was unable to sell more than an occasional painting. He therefore supported himself by providing illustrations for magazine stories and advertisements. For a while he learned etching with Martin Lewis. From these studies, he developed a better sense of how light plays on surfaces, especially at night. He also began to define spaces more distinctly than the impressionists that he had hitherto been following.

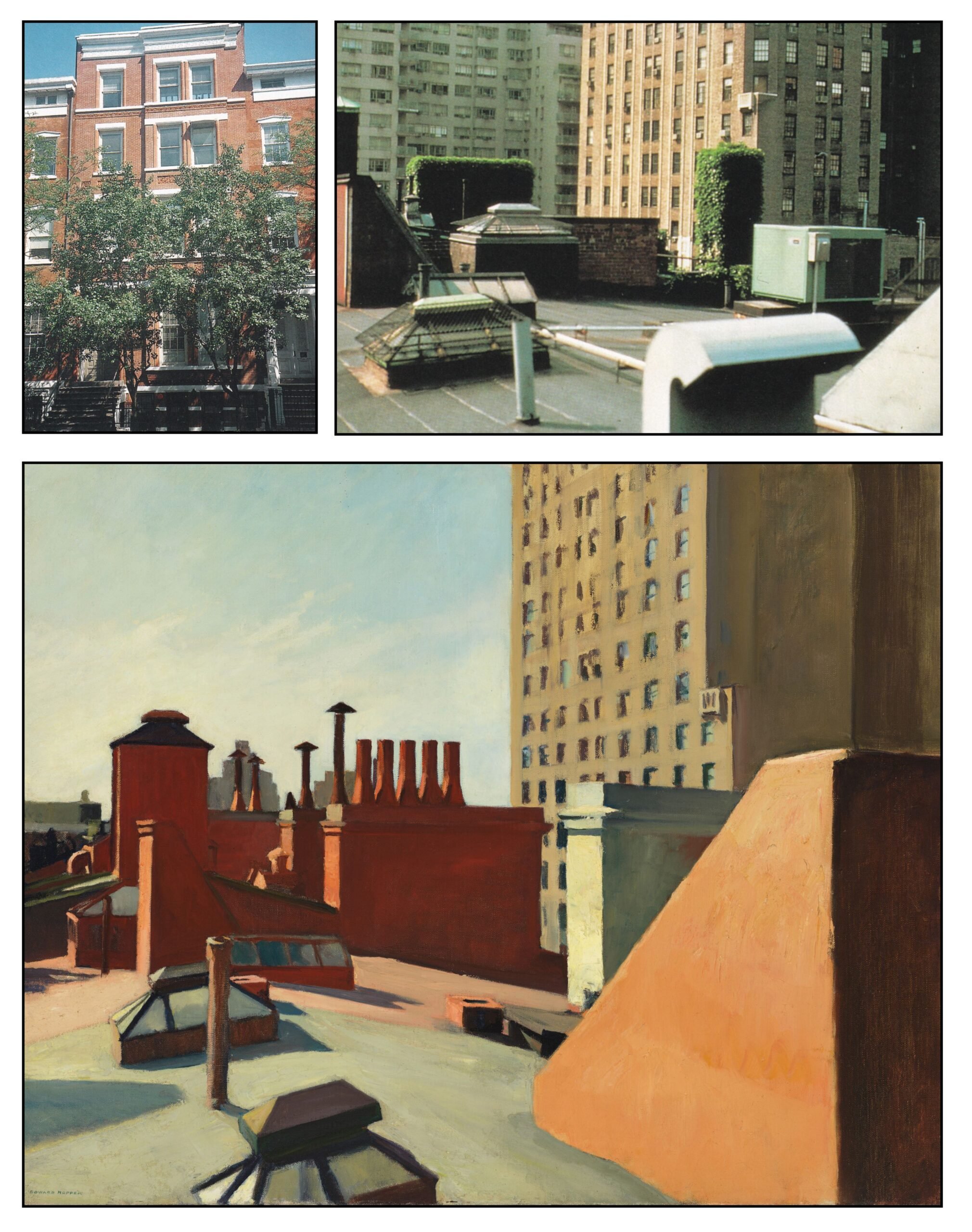

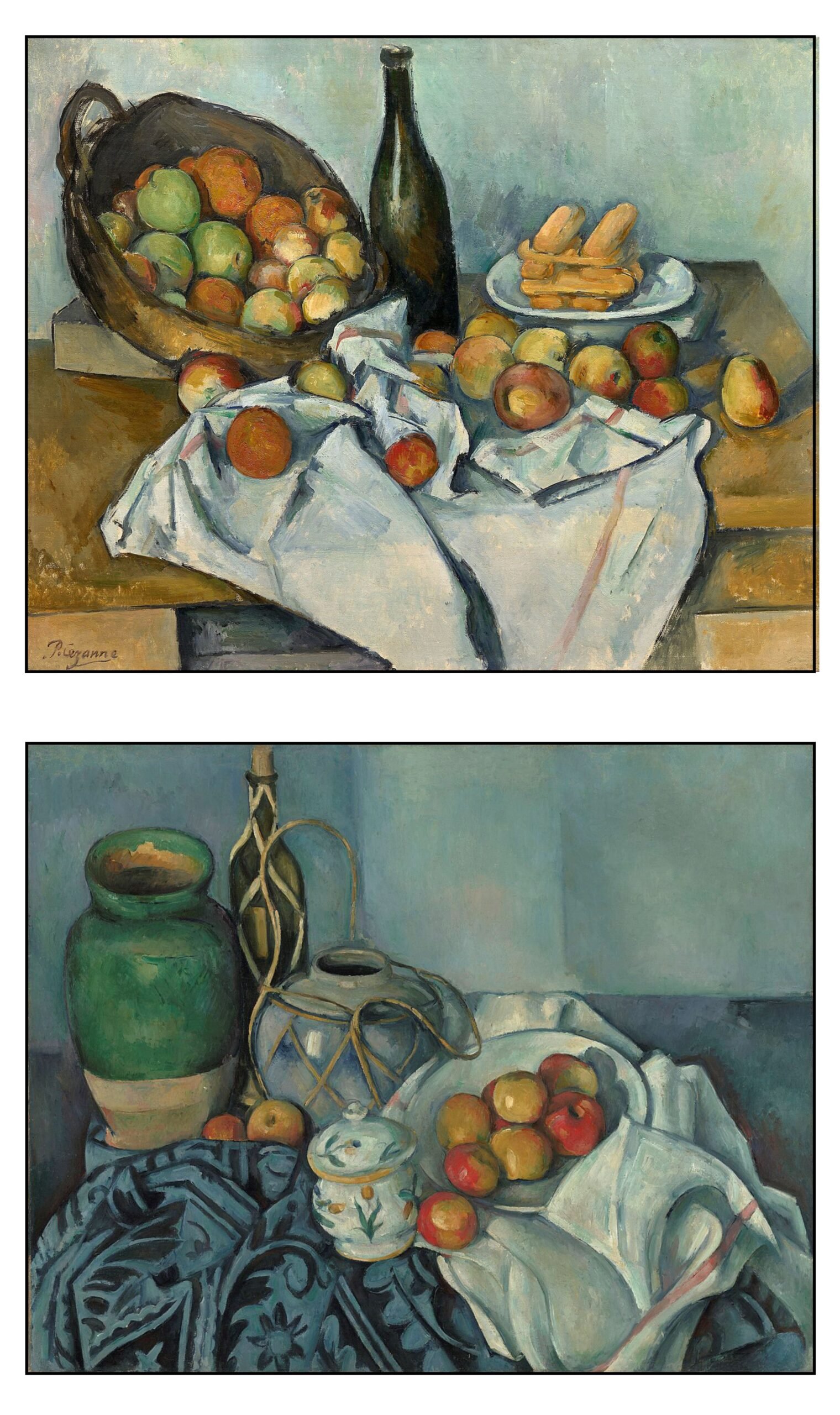

In 1913, Hopper moved into the top floor of Number 3, Washington Square North, Greenwich Village. This was his studio and residence for the rest of his life. The following illustration shows the building, the roof-top view from the top floor (Levin, 1985) and Hopper’s 1932 painting City Roofs:

Jo Nivison

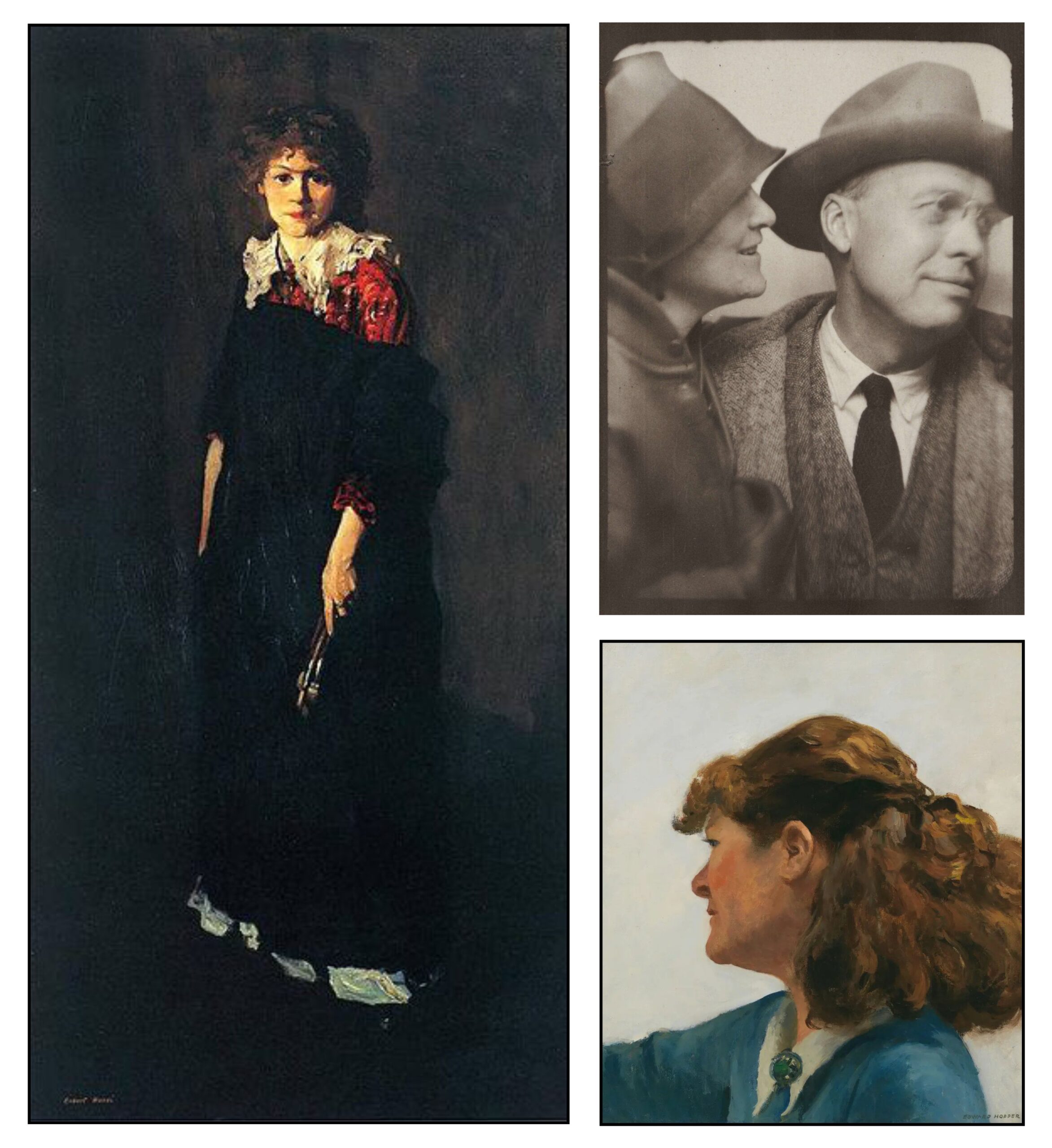

In the summer of 1923 on a painting trip to Gloucester, Massachusetts, Hopper re-encountered Jo Nivison, who had been a fellow-student at the New York School of Art and Design. They both painted water-colors and on their return to New York, Nivison was instrumental in getting Hopper’s work exhibited. They enjoyed each other’s company and were married in 1924. Both were 41 years old. They were physically and psychologically different: he was 6 ft 5 inches while she was just 5 ft; “she was gregarious, outgoing, sociable and talkative, while he was shy, quiet, solitary, and introspective” (Levin, 2007, p 168). The following illustration shows a 1906 portrait of: The Art Student Miss Josephine Nivison by Robert Henri, a photograph of Jo and Edward (from the 1930s), and a 1936 painting of Jo Painting by Hopper.

Edward painted and Jo took care of things. She modelled for his figure paintings, and kept meticulous records of his paintings in a set of notebooks. She sometimes rebelled against her help-mate status, and urged her husband to promote her own artistic career. There were arguments, some of which degenerated into physical fights. Nevertheless, their marriage lasted until Edward’s death in 1967. Jo died a year later, leaving all her husband’s unsold paintings to the Whitney Museum of American Art. The museum also accepted her paintings, but many of these were discarded. Jo Hopper was not given the recognition that she deserved (Colleary, 2004; Levin, 1980b, 2007, pp. 717-728; McColl, 2018).

Working Methods

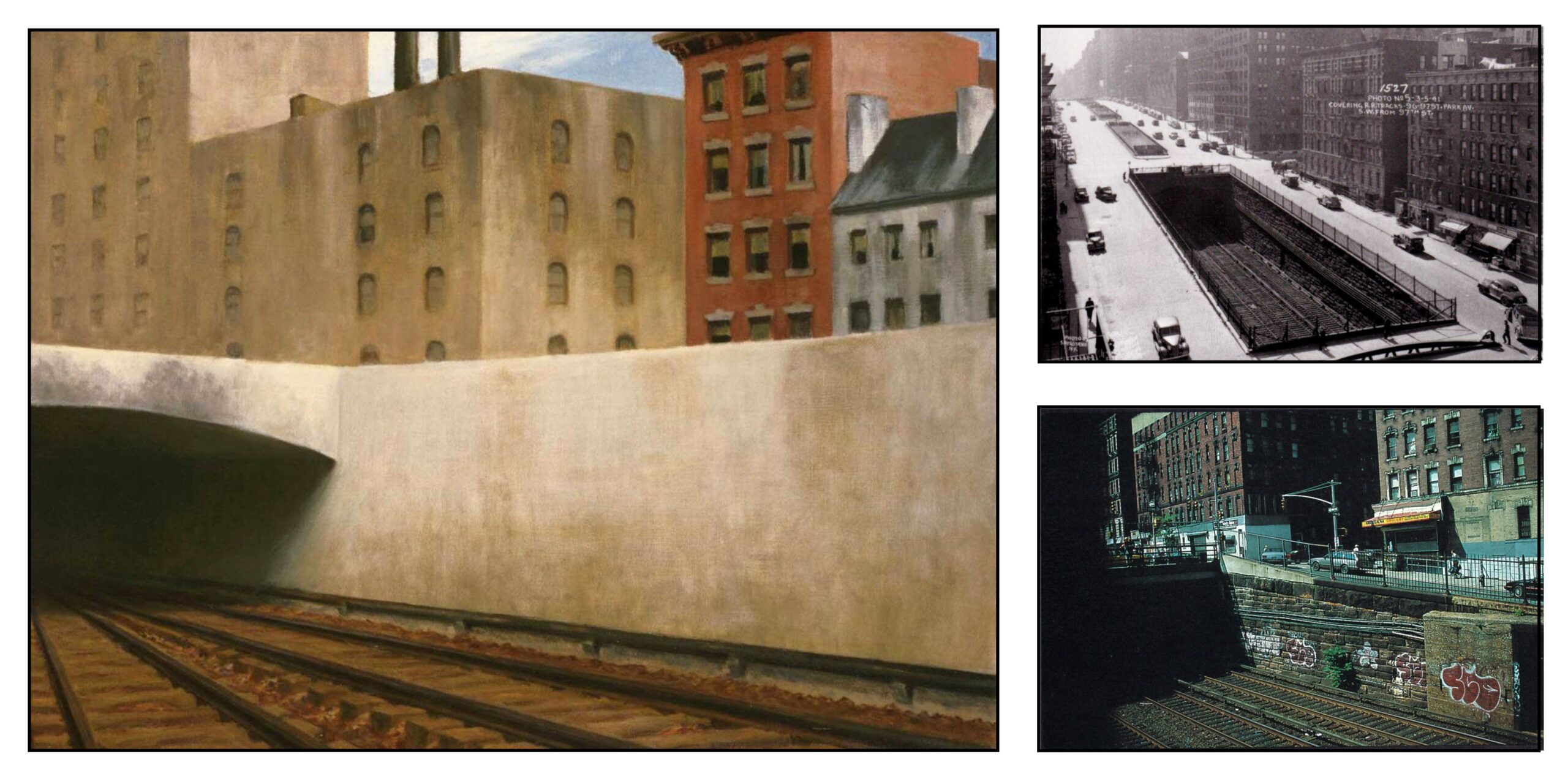

Although Hopper worked en plein air in France and during his summer excursions to New England, most of his pictures were painted in the studio from sketches made in situ. His images are thus based on reality but tempered by the imagination. The perspectives are altered; the surfaces are simplified and flattened; the colors are changed to what they might have been rather than what they were. His 1946 painting Approaching a City shows the rail lines of the Metro-North Railroad entering the tunnel at 97th Street to travel under Park Avenue to Grand Central Station. The painting provides a heightened representation of what a traveler might experience coming into a city for the first time. The illustration below shows the painting together with contemporary (Conaty,2022, p 13) and more recent (Levin, 1985) views of the scene.

The perspective of the painting would only be possible from the level of the rail-lines. Hopper has tried to see from the point of view of a passenger in a train rather than a pedestrian on Park Avenue. Even if the graffiti were erased, the opposite wall is (and was) not as it appears in the painting. Hopper has flattened its texture and removed the cables. The buildings above the wall are not those on Park Avenue, either now or when the painting was made. Conaty (2022, p 13) remarks

Here. the building types – from the nineteenth century brownstone to the modern industrial structure at the far left – suggest the passage of time in the histories that coexist, pictured as a single mass of forms seen from the train track below.

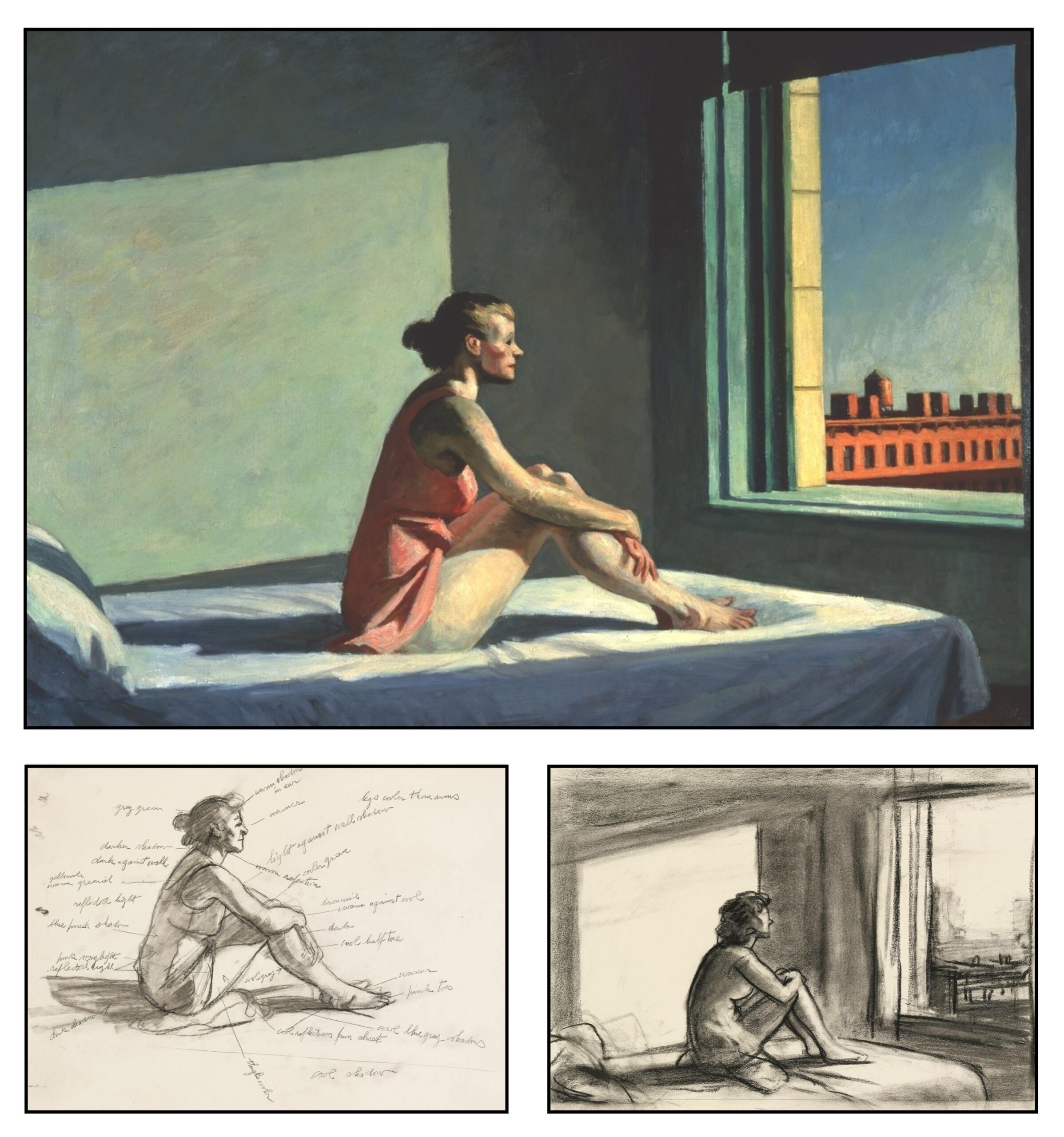

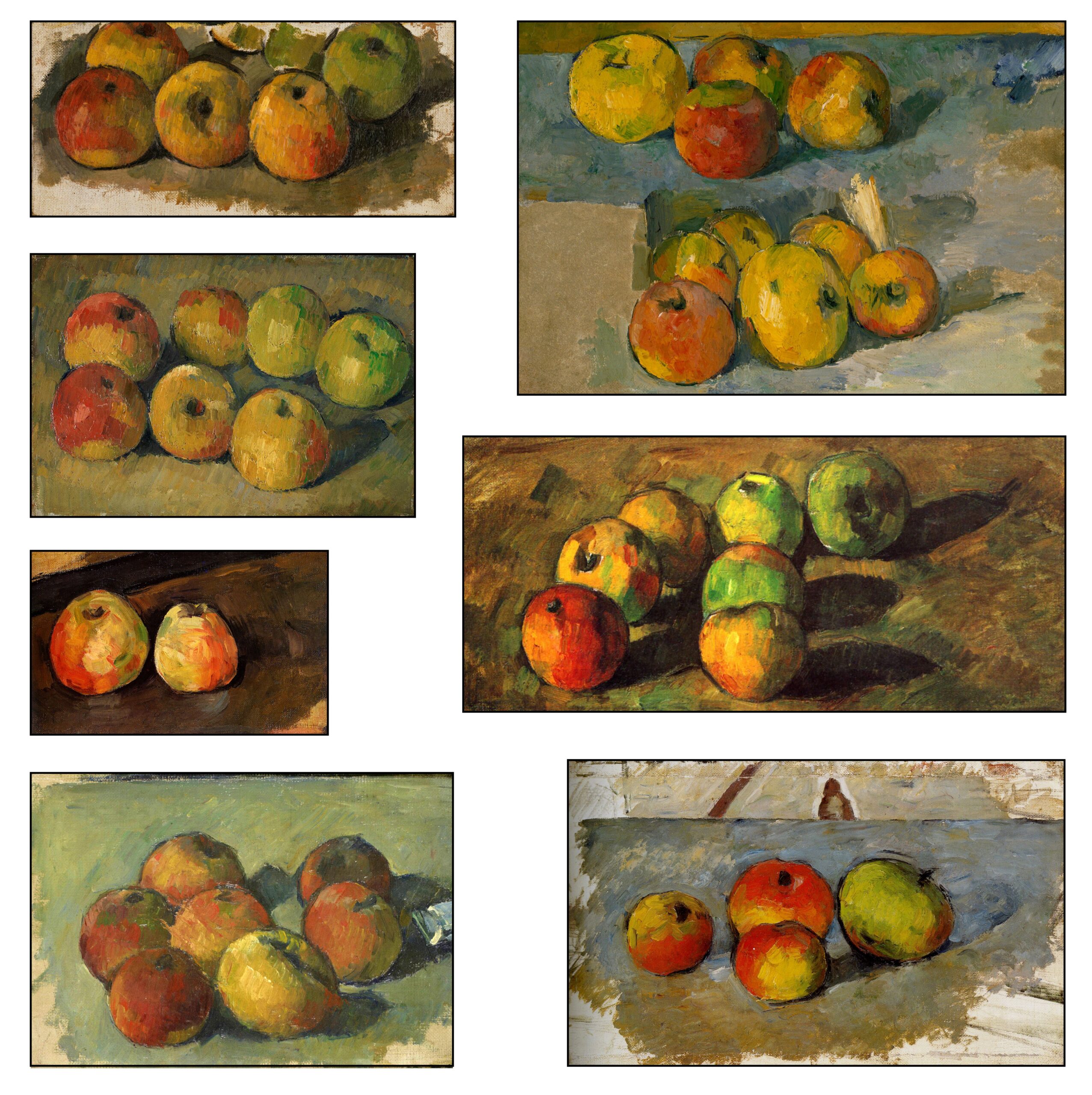

The illustration below shows Hopper’s 1954 painting Morning Sun. The preparatory sketches show both the general layout of the room the effects of the bright morning light, and a more accurate representation of the model (Jo) with extensive details about shading and color:

The Lonely City

Although Hopper painted many different subjects, he is best known for his pictures of lonely urban surroundings. The most recent exhibition of his work at the Whitney Museum focuses on his depiction of New York City (Conaty, 2022).

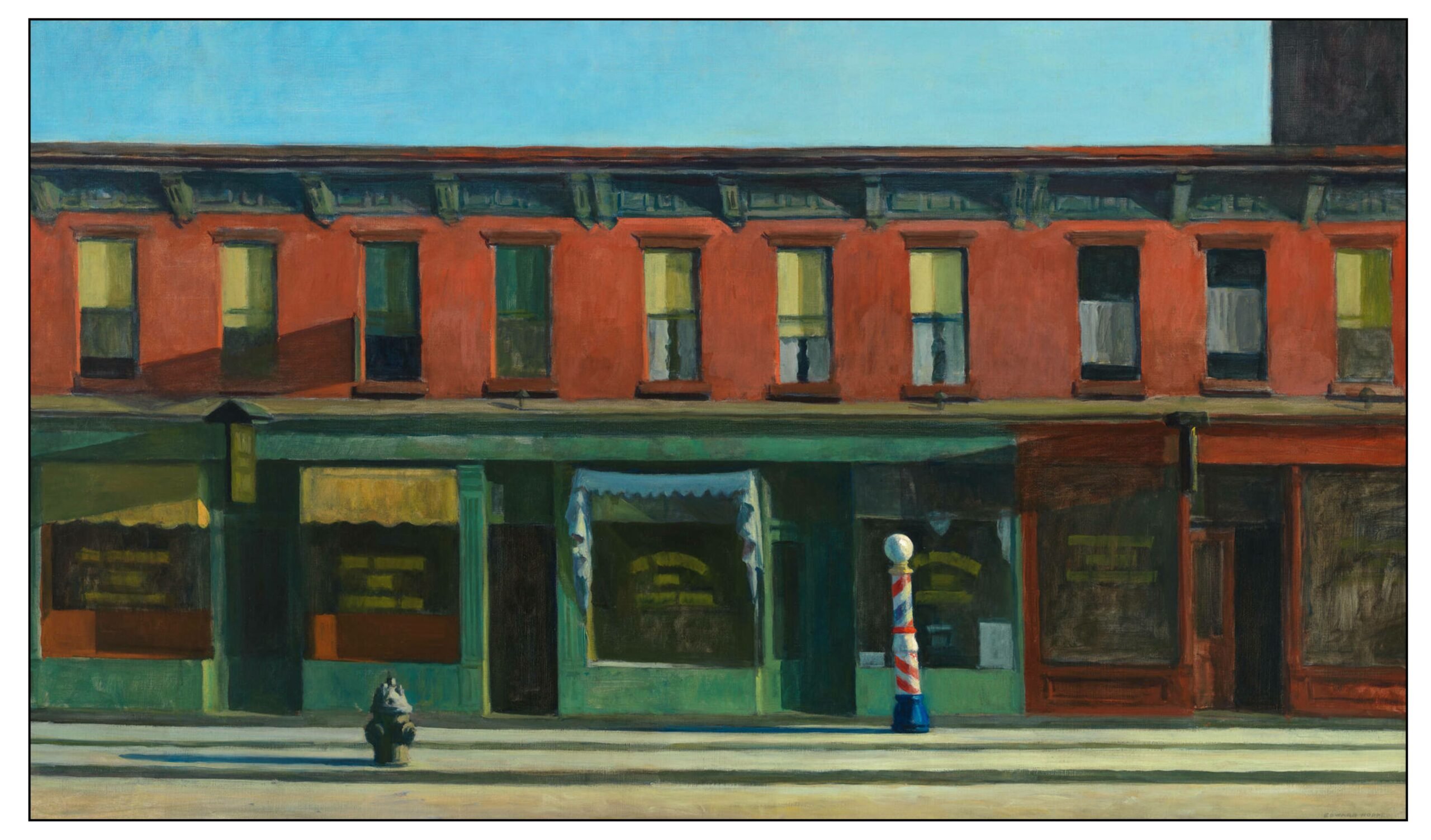

The 1930 painting Early Sunday Morning shows a deserted New York Street. Though long considered to represent 7th Avenue in Greenwich Village, recent evidence has pointed to a source on Bleeker Street (Marcum 2022). The painting has a wonderful visual rhythm: the repetition and variation between the different units and their windows reminds me of the stanzas and rhymes of poetry.

John Updike (2005 p 199) describes the painting:

Early Sunday Morning is a literally sunny picture, with even something merry about it: bucolic peace visits a humdrum urban street. We are gladdened by the day that is coming, entering from the right, heralded by the shadows it throws. The glow on the sidewalk is picked up by the yellow window shades. The barber pole is cheerful, the hydrant basks like a sluggish, knobby toad. But the silent windows, especially the darkened big shopwindows, hold behind them an ominous mortuary stillness. The undercurrents of stillness threaten to drag us down, even as the day dawns. The diurnal wheel turns, taking the sun on one of its sides. But the other side, the side where sun is absent, has its presence, too, and Hopper’s apparently noncommittal art excels in making us aware of the elsewhere, the missing, the longed-for. He is, to use a phrase generally reserved for writers, a master of suspense.

The painting takes liberties with the shadows. Neither 7th Avenue nor Bleeker Street run directly east-west, and the morning sun could not cast shadows so long and so parallel to the buildings in either place. As noted by the poet John Hollander (in Levin 1995 p 43), the long shadow on the sidewalk is especially mysterious:

Long, slant shadows

Cast on the wan concrete

Are of nearby fallen

Verticals not ourselves.

Lying longest, most still,

Along the unsigned blank

Of sidewalk, the narrowed

Finger of shade left by

Something, thicker than trees,

Taller than these streetlamps,

Somewhere off to the right

Perhaps, and unlike an

Intrusion of ourselves,

Unseen, long, is claiming

It all, the scene, the whole.

A striking aspect of the painting is it overwhelming silence: the calm before or after the storm of normal life. Ward (2017, p 169) remarks

Hopper’s paintings are uniquely silent, conveying a sense of unnatural stillness. The silence is more active than passive, mainly because it suggests little of the calmness, tranquility, or placidity commonly associated with it. Hopper’s silences are tense—hushed decorums maintained with terrific strain.

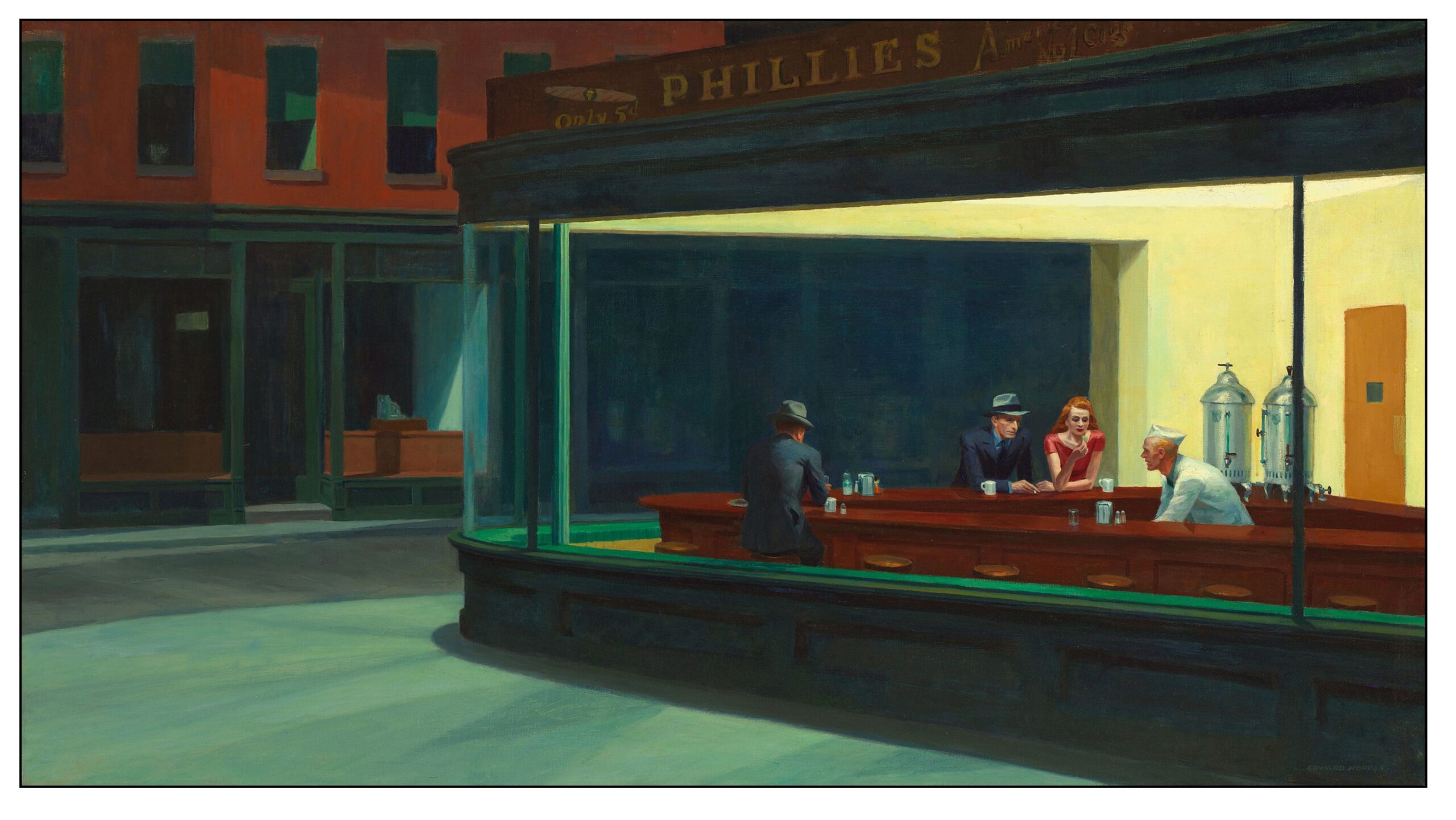

Probably Hopper’s most famous painting is The Nighthawks (1942), wherein a man and a woman sit at the counter of an all-night diner. They are served by a young waiter and observed by a solitary man at the other end of the counter. The diner is brightly lit; outside it is dark. The streets are deserted: it is likely long past midnight. We sense the couple’s anxiety and we are grateful for the light.

Hopper may have based the painting on a restaurant near the intersection of Greenwich Avenue and 7th Avenue (now Mulry Square). More likely it is an amalgam of various diners in the area. The title apparently comes from the beak-like nose of the man sitting with the woman.

The poet Mark Strand (1994, pp. 6-7) described the general effect of the picture:

The dominant feature of the scene is the long window through which we see the diner. It covers two-thirds of the canvas, forming the geometrical shape of an isosceles trapezoid, which establishes the directional pull of the painting, toward a vanishing point that cannot be witnessed, but must be imagined. Our eye travels along the face of the glass, moving from right to left, urged on by the converging sides of the trapezoid, the green tile, the counter, the row of round stools that mimic our footsteps, and the yellow-white neon glare along the top. We are not drawn into the diner but are led alongside it. Like so many scenes we register in passing, its sudden, immediate clarity absorbs us, momentarily isolating us from everything else, and then releases us to continue on our way. In Nighthawks, however, we are not easily released. The long sides of the trapezoid slant toward each other but never join, leaving the viewer midway in their trajectory. The vanishing point, like the end of the viewer’s journey or walk, is in an unreal and unrealizable place, somewhere off the canvas, out of the picture. The diner is an island of light distracting whoever might be walking by—in this case, ourselves—from journey’s end. This distraction might be construed as salvation. For a vanishing point is not just where converging lines meet, it is also where we cease to be, the end of each of our individual journeys. Looking at Nighthawks, we are suspended between contradictory imperatives—one, governed by the trapezoid, that urges us forward, and the other, governed by the image of a light place in a dark city, that urges us to stay.

Night makes us aware of our insignificance. A café can fend off these feelings. The older waiter in Hemingway’s story A Clean, Well-Lighted Place (1933) notes how his café provides an elderly customer with some sense of security in the night:

It is the light of course but it is necessary that the place be clean and pleasant. You do not want music. Certainly you do not want music. Nor can you stand before a bar with dignity although that is all that is provided for these hours. What did he fear? It was not fear or dread. It was a nothing that he knew too well. It was all a nothing and a man was nothing too. It was only that and light was all it needed and a certain cleanness and order. Some lived in it and never felt it but he knew it all was nada y pues nada y nada y pues nada. [nothing and then nothing and then nothing]

Strong (1988) remarks on the similarities between the isolation of Hopper’s images and the loneliness of Robert Frost’s poems. Hopper read and admired Frost’s poems. Jo Nivison painted a picture of him reading Frost in 1955 (Levin, 1980b). Frost’s poem Desert Places (1934) ends:

And lonely as it is, that loneliness

Will be more lonely ere it will be less –

A blanker whiteness of benighted snow

With no expression, nothing to express.

They cannot scare me with their empty spaces

Between stars – on stars where no human race is.

I have it in me so much nearer home

To scare myself with my own desert places.

There is something essentially American about the lonely individualism – the internal desert places – of Hopper, Hemingway and Frost.

Ecphrasis

Ecphrasis (Greek: words about) is the verbal description of a work of art, either real or imagined, expressed in vivid poetic language (Heffernan, 2015; Hollander 1988, 1995; Hollander & Weber, 2001; Panagiolidou, 2013). Ecphrasis is concerned with the effects the art on the viewer whereas “interpretation” deals with the what and how of these efects (Carrier, 1987).

Perhaps more than any other artist, Hopper has stimulated the imagination of poets and writers. Poems and stories written in response to his paintings have been collected in several anthologies (Block, 2016; Levin, 1995; Lyons et al., 1995), and individual poets have composed whole books inspired by his images (Farrés, 2009; Hoggard, 2009; Strand, 1994). The following are three examples of Hopper’s images and the poetry and prose that they have evoked.

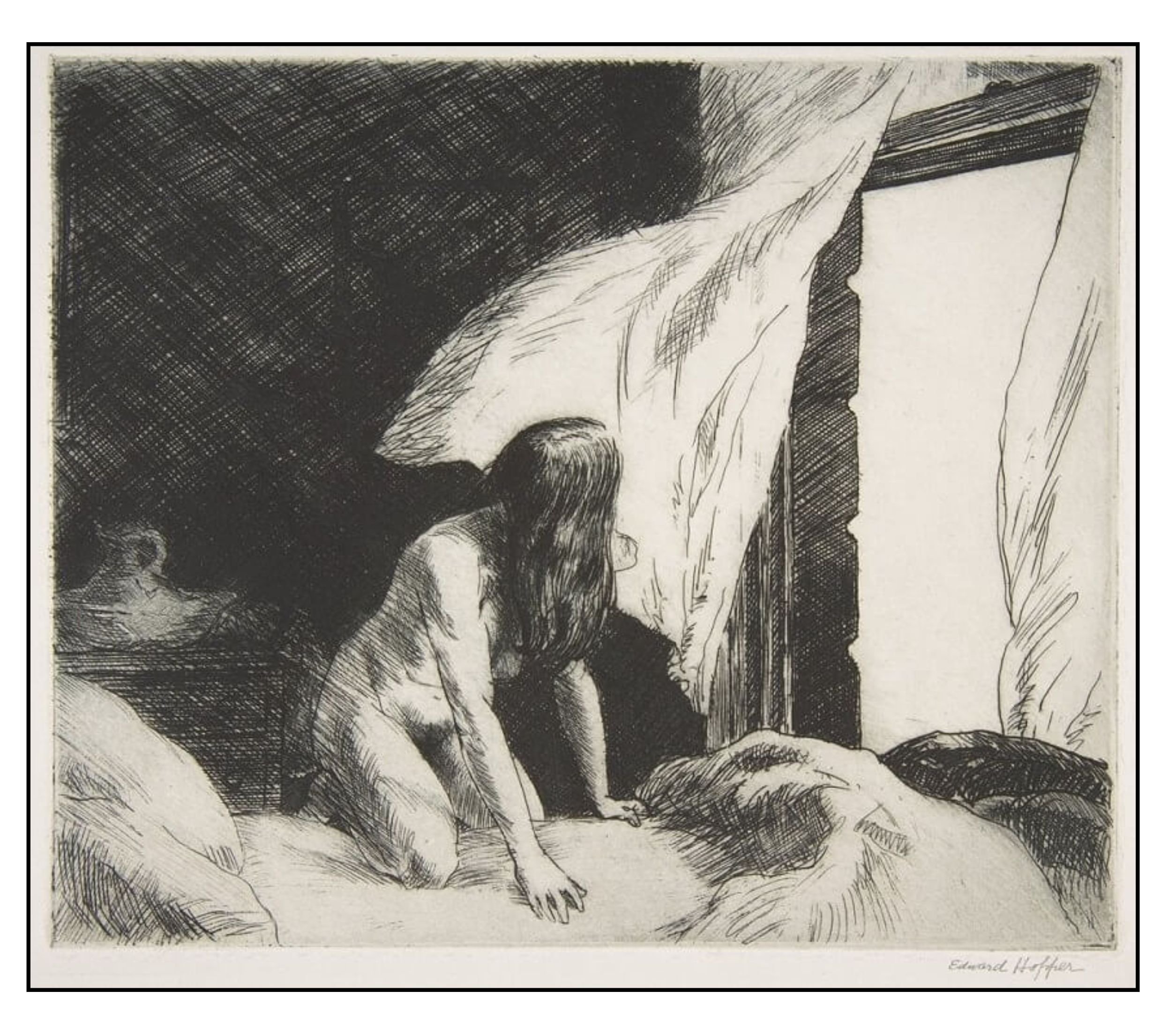

Hopper’s 1921 etching Evening Wind shows a nude woman about to lie down in bed as the wind blows the curtain into the room. The viewer feels that he is in the same room as the woman, and this intimacy recalls Degas’ paintings of women bathing. The Hopper website suggests that the sudden interruption of the wind might be akin to the appearance of a god, like the annunciation to Mary or the shower of gold that fell upon Danae.

Robert Mezey (Levin, 1995, p 24) describes the etching in a beautifully constructed sonnet:

One foot on the floor, one knee in bed,

Bent forward on both hands as if to leap

Into a heaven of silken cloud, or keep

An old appointment — tryst, one almost said —

Some promise, some entanglement that led

In broad daylight to privacy and sleep,

To dreams of love, the rapture of the deep,

Oh, everything, that must be left unsaid —

Why then does she suddenly look aside

At a white window full of empty space

And curtains swaying inward? Does she sense

In darkening air the vast indifference

That enters in and will not be denied,

To breathe unseen upon her nakedness?

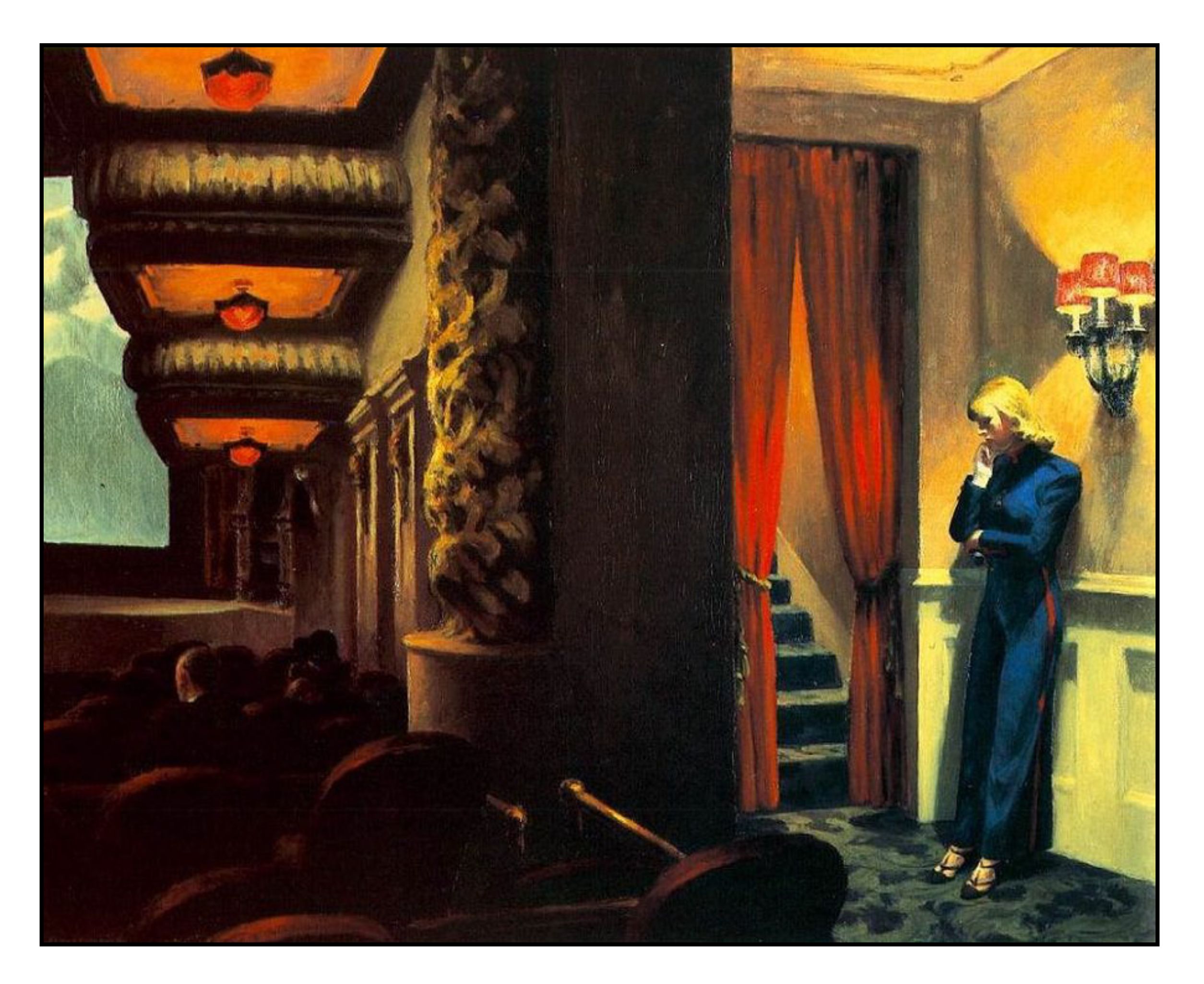

Hopper’s 1939 painting New York Movie depicts an usherette at one of the grand movie theaters in New York. She is standing beautifully and pensively near the side exit.

Leonard Michaels (Lyons et al, 1995, p 3) wonders about who she might be:

Of course, she wasn’t going anywhere. I mean only that there was drama in the painting, a kind of personal story, and it was more engaging, more psychologically intense, than the movie on the distant blurry screen, a rectangle near the upper left corner of the painting, like a window in a dark room. The usherette isn’t looking at that movie, isn’t involved with any movie drama, any mechanical story told with cuts and fades while music works on your feelings. Her drama is mythical, the myth of Eurydice doomed to wait at the edge of darkness. The red flashes in the shadows of the painting are streaks of fire and streams and gouts of blood. Eurydice stands at the edge of Hades waiting for Orpheus. This movie theater, like many others in Hopper’s day, is called the Orpheum.

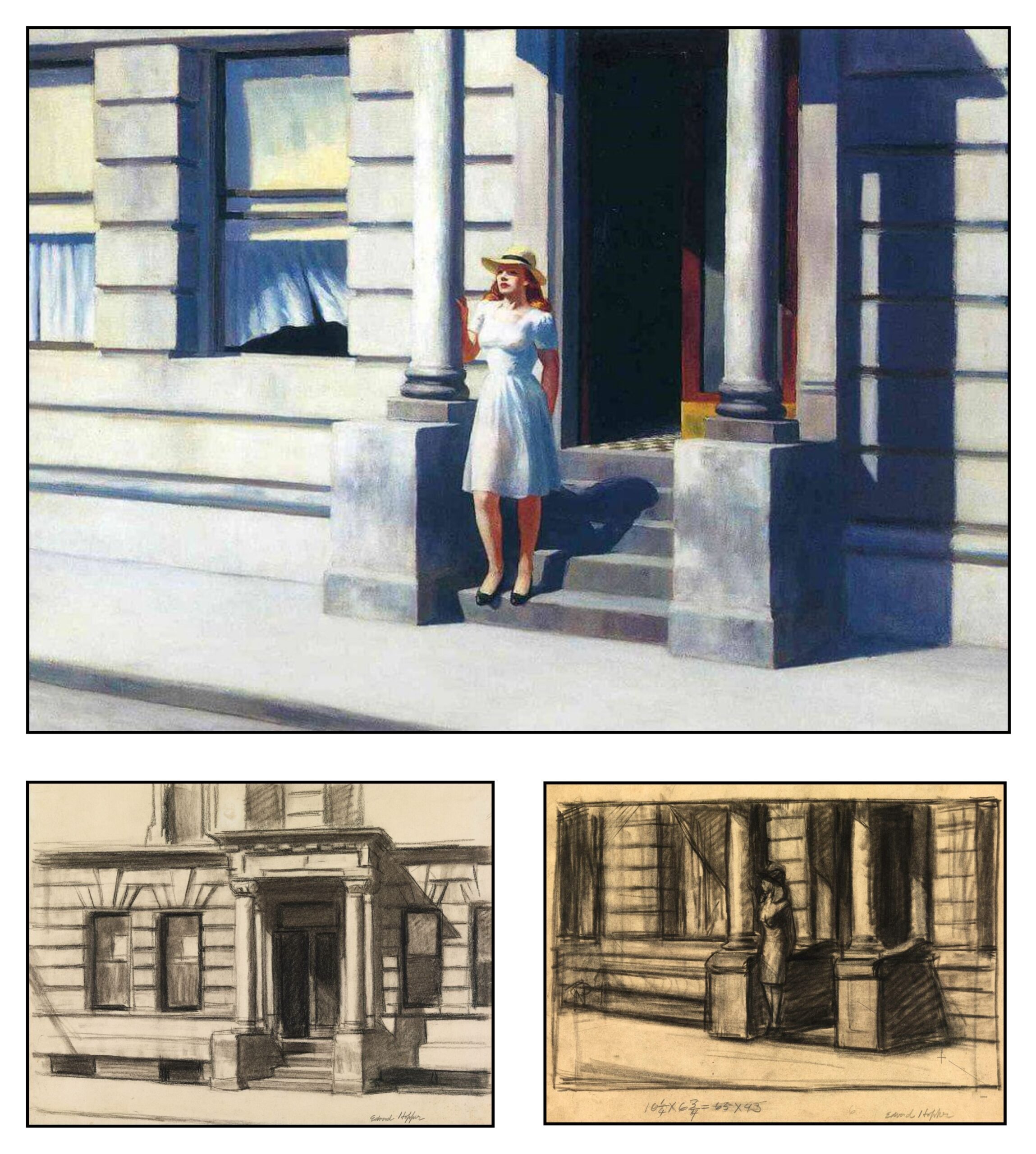

The 1943 painting of Summertime shows a young woman in a thin dress standing at the door of a New York building. She is about to face the day. She feels warm but a cooling breeze blows the dress against her body.

James Hoggard (2009) imagines Hopper talking about his painting:

It’s good you noticed, if you did

A number, I’ll say, have not come close

This one’s a nude, the clothes a guise,

a mask, a witty, illusory stab

at idiot propriety — imagination strips

everything bare, as I’ve done here:

the nipples and heft of breasts in view

and the screaming delight of thighs

rising toward the truth between them,

as suggested by the curtain’s cleft —

all this a celebration of my mood,

and my mood trumps anything that’s yours

This lass, who looks sweetly nubile now,

is Jo, my wife, whose age has been reduced

by the cleverness of my brush and paint

I’ve stripped her nearly bare, but I

have also preserved defiant ghosts

in the willful set of her swelling lips

The tensions and songs here are mine

You can do with your own what you will

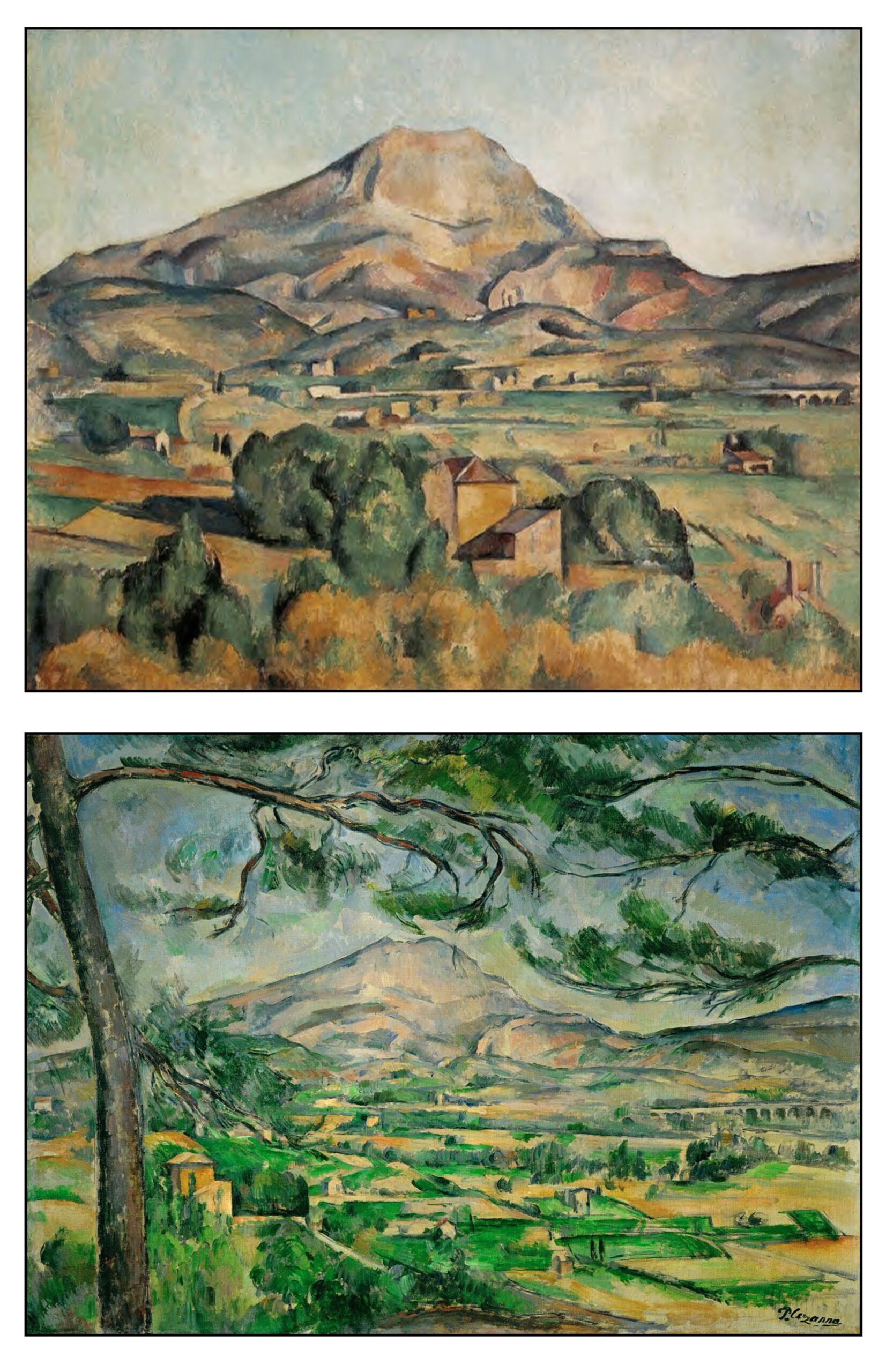

Homage in Film and Photography

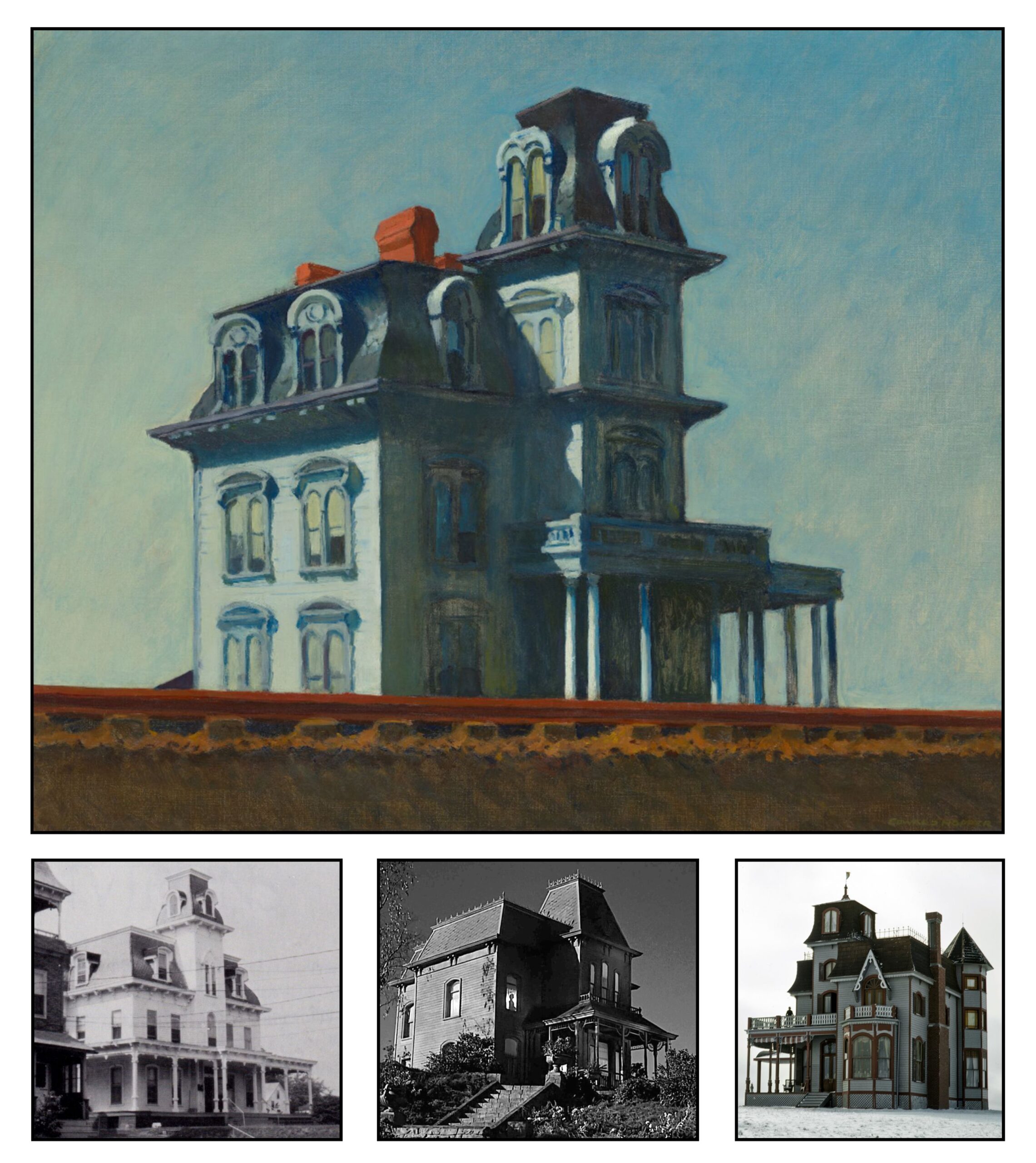

Hopper’s work has had a large influence on the visual arts as well as on poetry. Many of Hopper’s paintings depict large ornate 19th-Century houses – often standing isolated from other buildings. One such picture is House by the Railroad (1925). According to Levin (1985) this was likely partially based on a house in Haverstraw just north of his home in Nyack (lower left of the illustration below). This house is across the street from the railway: Hopper often compressed the distances between things in his paintings. The Mansard roof and central tower and columned porch were also found in other houses that Hopper painted. These houses defiantly insists on their isolated existence.

Variations on this house have appeared in several movies: most importantly Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Terrence Malick’s Days of Heaven (1978). These sets are shown in the illustration above (lower middle and lower right).

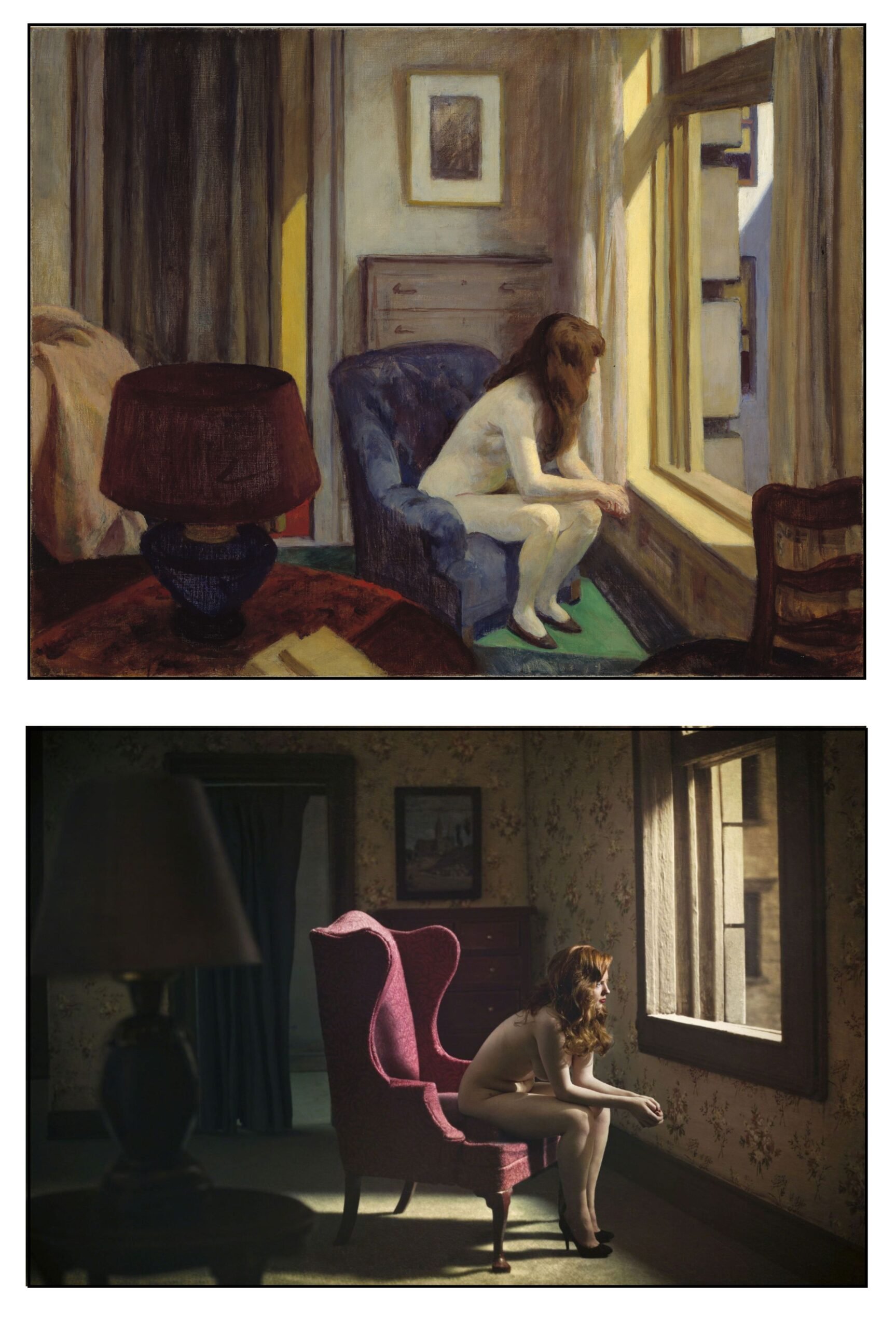

Many photographers have been profoundly influenced by Hopper’s pictures. Phillip Lorcia diCorcia photographs isolated people in urban settings: his images suggest what Hopper might have seen he had lived a further fifty years (Llorens & Ottinger 2012, pp. 306-309). Even more recently, the photographer Richard Tuschman has recreated many of Hopper’s paintings in photographs. The illustration below shows Hopper’s 1926 painting Eleven a.m. together with Tuschman’s Woman at a Window, 2013. The chair has changed from blue to pink and the model now wears heels. Most importantly her face is visible.

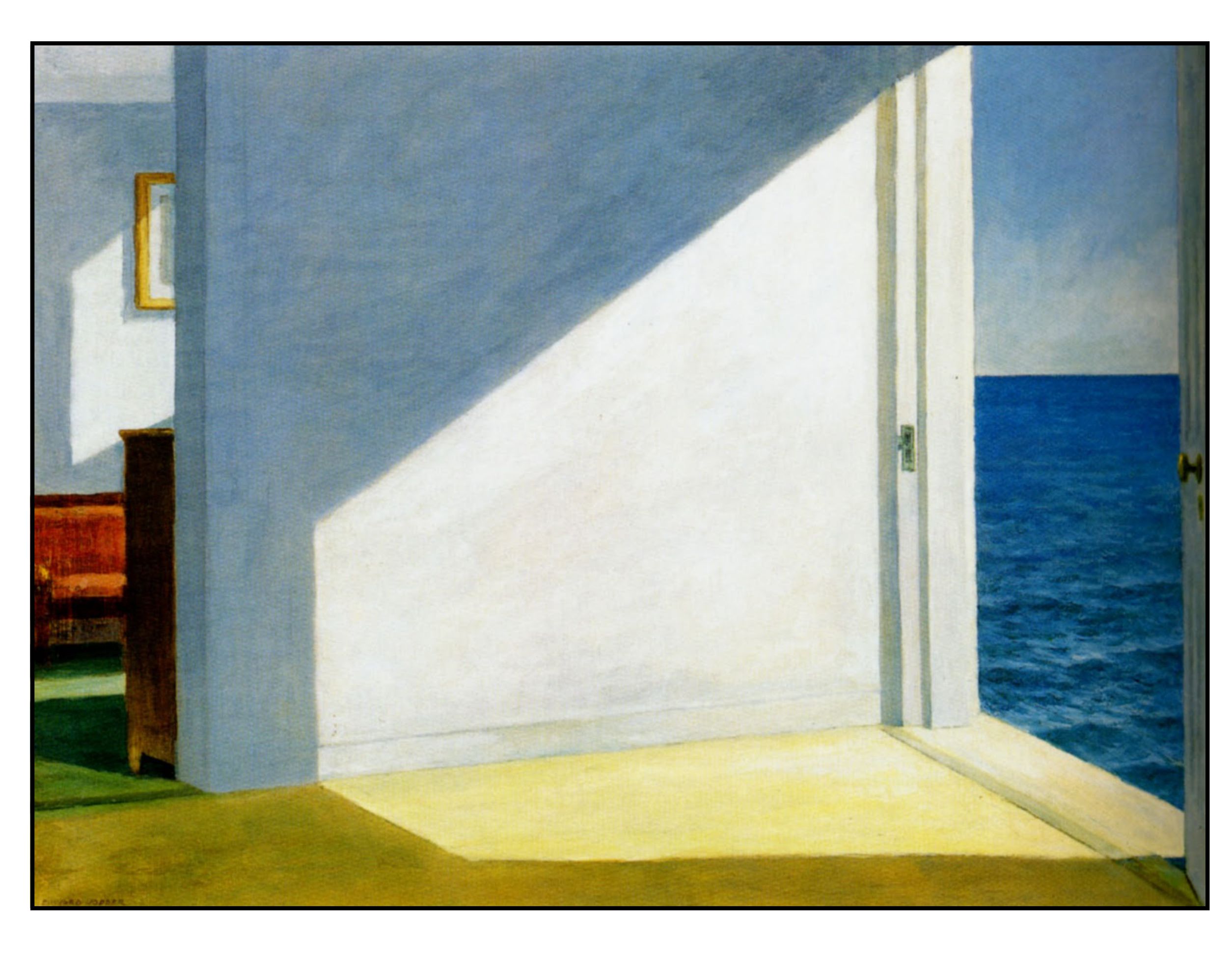

Empty Rooms

Hopper was always intrigued by the play of light in empty rooms. His 1951 painting Rooms by the Sea, shows an empty room leading through an open door to the sea. The image derives from the Hopper’s studio in Truro on Cape Cod. The door does not directly open onto the sea: Hopper has compressed the space. The main room in the painting is completely bare. On the left, however, another room can be glimpsed with a couch, a chest-of-drawers, and a painting on the wall. Hollander (2001, pp. 72-25) suggests that the two rooms might represent the memories of the past and the presentiments of the future.

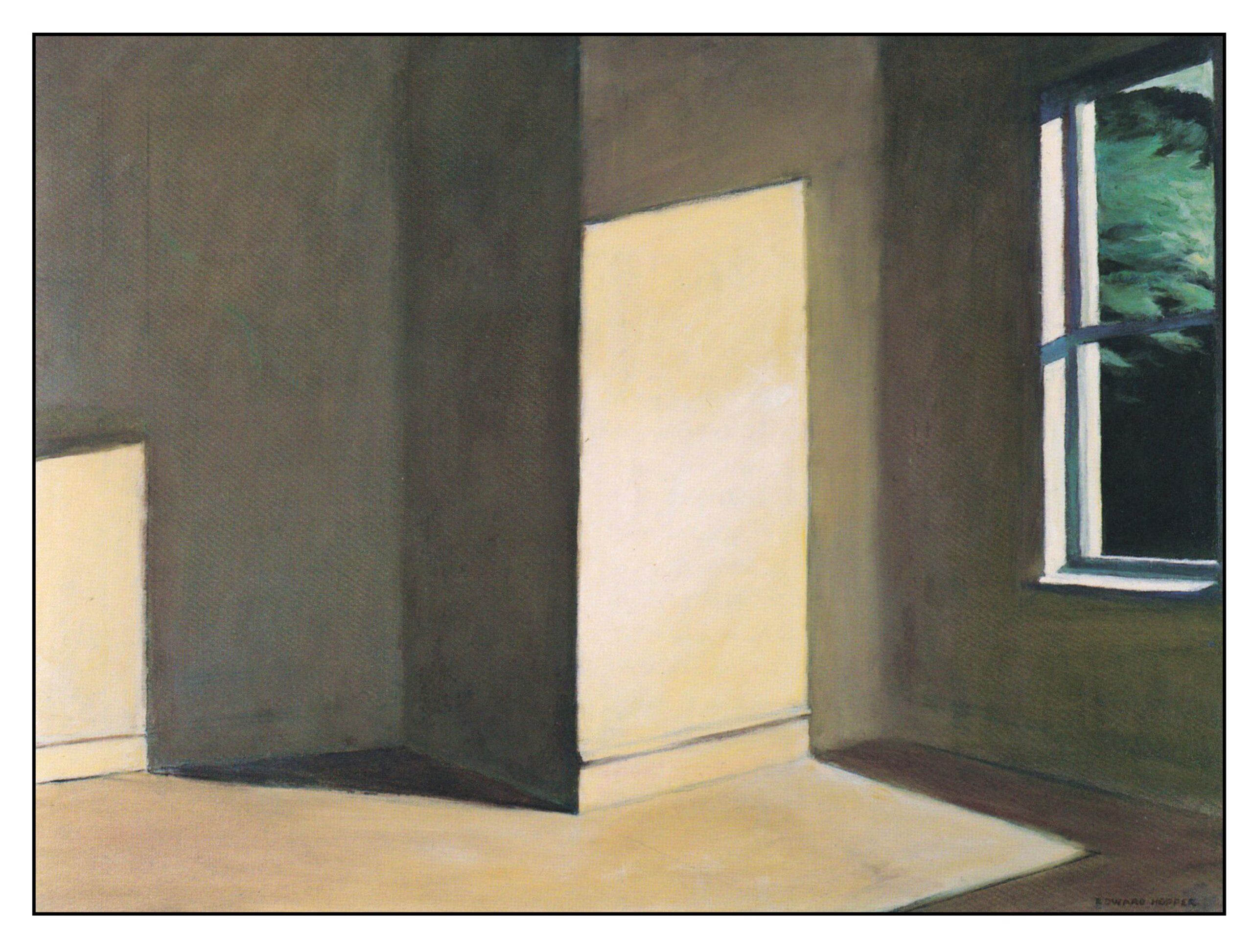

One of Hopper’s late paintings Sun in an Empty Room (1963) is devoid of detail. The room contains nothing but the light. The stark simplicity almost approaches the abstract, though Hopper would insist that the image is still tied to reality.

Strand (1994, pp. 57-58) remarks:

In the later painting, Sun in an Empty Room, there is nothing calming about the light. It comes in a window and falls twice in the same room—on a wall close to the window and on a slightly recessed wall. That is all the action there is. We do not travel the same distance—actual or metaphorical—that we do in Rooms by the Sea. The light strikes two places at once, and we feel its terminal character instead of anything that hints of continuation. If it suggests a rhythm, it is a rhythm cut short. The room seems cropped, as if the foreground were cut away. What we have is a window wall, with the window framing the highlighted leaves of a nearby tree, and a back wall, a finality against which two tomblike parallelograms of light stand up-right. Done in 1963, it is Hopper’s last great painting, a vision of the world without us; not merely a place that excludes us, but a place emptied of us. The light, now a faded yellow against sepia-toned walls, seems to be enacting the last stages of its transience, its own stark narrative coming to a close.

Last Things

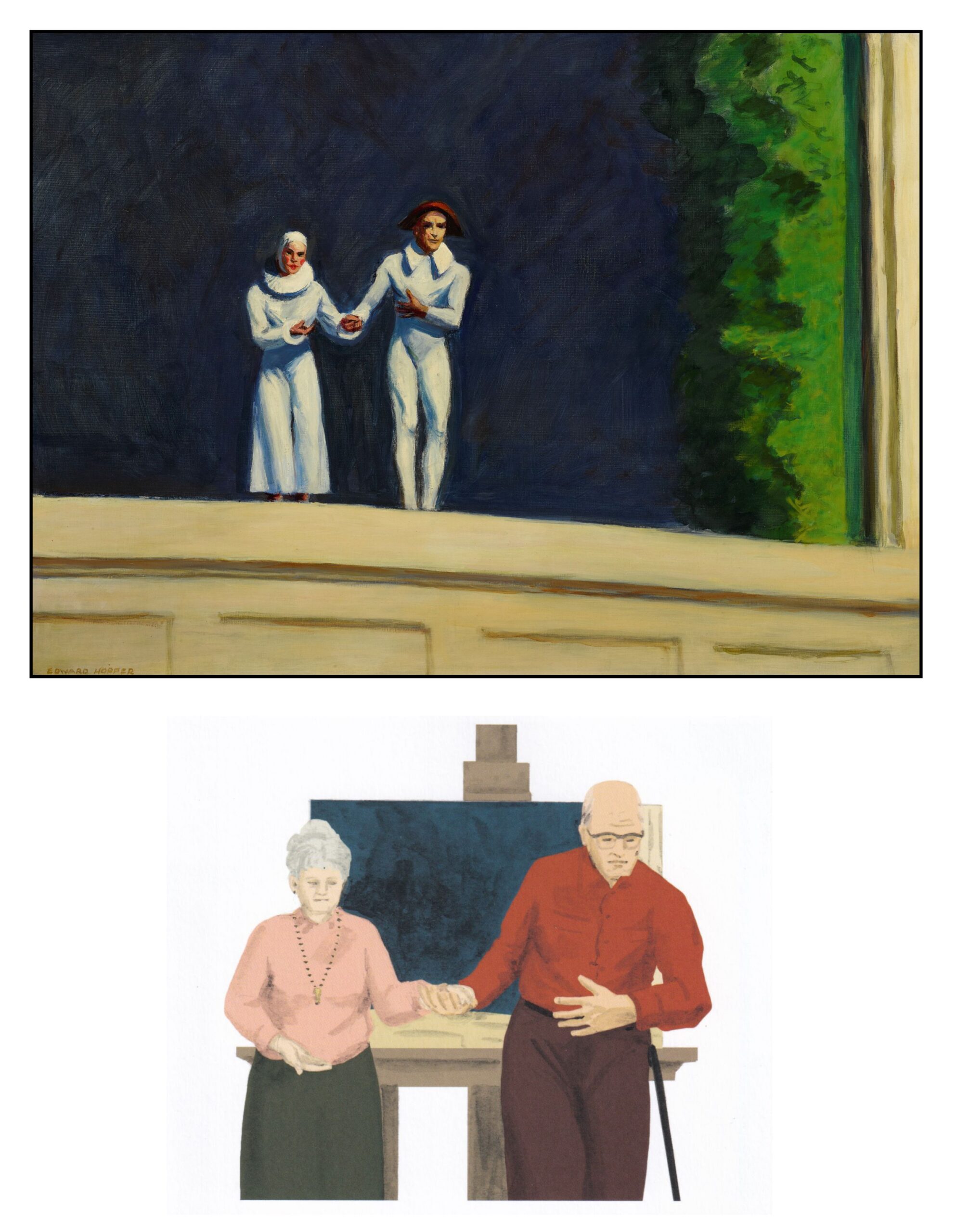

Hopper’s last painting, Two Comedians (1965) portrays two actors taking their bows on a stage raised high above the audience. They actors are the artist and his wife. Representing himself as a comedian refers back to his earlier painting Soir Bleu. The illustration below shows the painting together with Scarduelli’s impression of the elderly couple in their studio (Rossi & Scarduelli, 2021).

The Portuguese poet Ernest Farrés (translated by Lawrence Venuti, 2006) imagines Hopper’s comments on the painting

Perhaps it’s the costume

that lets me laugh,

or smile as it were —

for me they’ve been the same

Perhaps it’s the clown’s disguise

that lets me be

looser than I usually am

strutting cock-proud now,

goofy-eyed at a crowd,

the illusion of a crowd

no one sees but you and me

Clowns, we move toward stage’s edge,

a place I’ve made like a roof’s edge,

with threat or promise of a fall

But the moment seems sweet,

our domestic wars almost done,

and white-clad and foolscapped,

we seem blest as we press

toward the last edge we’ll meet,

our lyrical selves always in France,

our final days just bibelots:

Nous sommes, Jo et moi, les pierrots

Final Words

Hopper painted the real world, but he allowed his imagination to interact with his perception. Conaty (2022, p 14) remarks that he often felt torn between working from the fact and improvising upon what he saw. Hopper argued against abstract expressionism, insisting that art should always have its source in “life.” The following is his 1953 statement on art from the short-lived magazine Reality (quoted in Llorens & Ettinger, 2012, p 275):

Great art is the outward expression of an inner life in the artist, and this inner life will result in his personal vision of the world. No amount of skillful invention can replace the essential element of imagination. One of the weaknesses of much abstract painting is the attempt to substitute the inventions of the intellect for a pristine imaginative conception. The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design. The term “life” as used in art is something not to be held in contempt, for it implies all of existence, and the province of art is to react to it and not to shun it. Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.

References

Block, L. (Ed.) (2016). In sunlight or in shadow: stories inspired by the paintings of Edward. Pegasus Books.

Carrier, D. (1987). Ekphrasis and interpretation: two modes of art history writing. British Journal of Aesthetics, 27(1), 20–31.

Colleary, E. T. (2004). Josephine Nivison Hopper: some newly discovered works. Woman’s Art Journal, 25(1), 3–11.

Conaty, K. (2022). Edward Hopper’s New York. Yale University Press.

Doss, E. L. (1983). Edward Hopper, Nighthawks, and Film Noir, Post Script: Essays in Film and the Humanities, 2 (2), 14–26

Farrés, E. (translated by L Venuti, 2009). Edward Hopper: Poems. Graywolf Press

Heffernan, J. A. W. (2015). Ekphrasis: Theory. In Rippl, G. (Ed.) Handbook of Intermediality. (pp. 35–49). De Gruyter.

Hoggard, J. (2009). Triangles of light: the Edward Hopper poems. Wings Press.

Hollander, J. (1988). The poetics of ekphrasis. Word & Image, 4(1), 209–219.

Hollander, J. (1995). The gazer’s spirit: poems speaking to silent works of art. University of Chicago Press.

Hollander, J., & Weber, J. (2001). Words for images: a gallery of poems. Yale University Art Gallery.

Kranzfelder, I. (2002). Edward Hopper: 1882-1967. Taschen.

Levin, G. (1980a). Edward Hopper: the art and the artist. Norton.

Levin, G. (1980b). Josephine Verstille Nivison Hopper. Woman’s Art Journal, 1(1), 28-32.

Levin, G. (1985, revised 1998). Hopper’s places. University of California.

Levin G. (1995). The poetry of solitude: a tribute to Edward Hopper. Universe Publishing.

Levin, G. (1995, revised 2007). Edward Hopper: an intimate biography. Rizzoli.

Llorens, T. & Ottinger, D. (2012). Hopper. Distributed Art Publishers.

Lyons, D., Weinberg, A. D., & Grau, J. (1995). Edward Hopper and the American imagination. Whitney Museum of American Art.

Marcum, A. (2022). Edward Hopper’s village: Early Sunday Morning on Bleecker Street. Village Preservation Blog.

McColl, S. (2018). Jo Hopper, Woman in the Sun. Paris Review, Feb 26, 2018.

Panagiotidou, M.-E. (2023). The poetics of ekphrasis: a stylistic approach. Springer International

Rossi, S., & Scarduelli, G. (2021). Edward Hopper: the story of his life. Prestel Verlag

Strand, M. (1994). Hopper. Ecco Press.

Strong, P. (1988). Robert Frost’s “Nighthawks”/Edward Hopper’s “Desert Places.” Colby Library Quarterly, 24(1), 27–35

Updike, J. (2005). Still looking: essays on American art. Knopf.

Ward, J. (2017). American Silences: the realism of James Agee, Walker Evans, and Edward Hopper. Taylor & Francis.