This posting considers Shakespeare’s Hamlet. The play has become as fascinating and as meaningful as any scripture (Bloom, 2003, p. 3). The character of its hero admits to numerous interpretations, both on the stage and in the critical literature.

Hamlet was the first clear representation of how human beings choose to act according to their own lights. We are not completely determined. Most of our actions follow willy-nilly from our past. Sometimes, however, we act as conscious agents: we consider the consequences of our actions, and choose the right act rather than the reflex.

I have discussed the concepts of freedom and determination in an earlier posting. These ideas are now considered in relation to Shakespeare’s Hamlet. This is the longest of my posts so far. My apologies. Forgive me my obsessions.

Interpreting Hamlet

Everyone wants to play Hamlet. Each actor plays him differently; no one fully understands him. Anyone who feels that he has him down pat does well to remember Hamlets upbraiding of Guildenstern, who thinks he knows the prince, but acknowledges that he cannot play the recorder:

Why, look you now, how unworthy a thing you make of me! You would play upon me; you would seem to know my stops; you would pluck out the heart of my mystery; you would sound me from my lowest note to the top of my compass: and there is much music, excellent voice, in this little organ; yet cannot you make it speak. ‘Sblood, do you think I am easier to be played on than a pipe? Call me what instrument you will, though you can fret me, yet you cannot play upon me.

Despite this warning,

They all want to play Hamlet.

They have not exactly seen their fathers killed

Nor their mothers in a frame-up to kill,

Nor an Ophelia lying with dust gagging the heart,

Not exactly the spinning circles of singing golden spiders,

Not exactly this have they got at nor the meaning of flowers—O flowers, flowers slung by a dancing girl—in the saddest play the inkfish, Shakespeare, ever wrote;

Yet they all want to play Hamlet because it is sad like all actors are sad and to stand by an open grave with a joker’s skull in the hand and then to say over slow and over slow wise, keen, beautiful words asking the heart that’s breaking, breaking,

This is something that calls and calls to their blood.

They are acting when they talk about it and they know it is acting to be particular about it and yet: They all want to play Hamlet.

Carl Sandburg (1922)

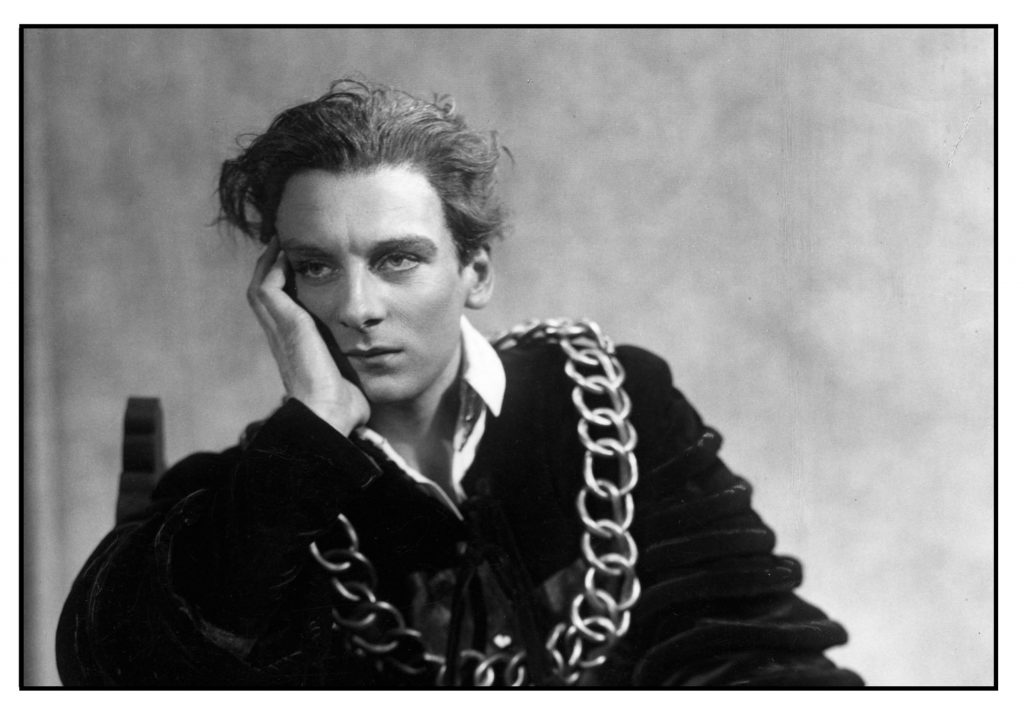

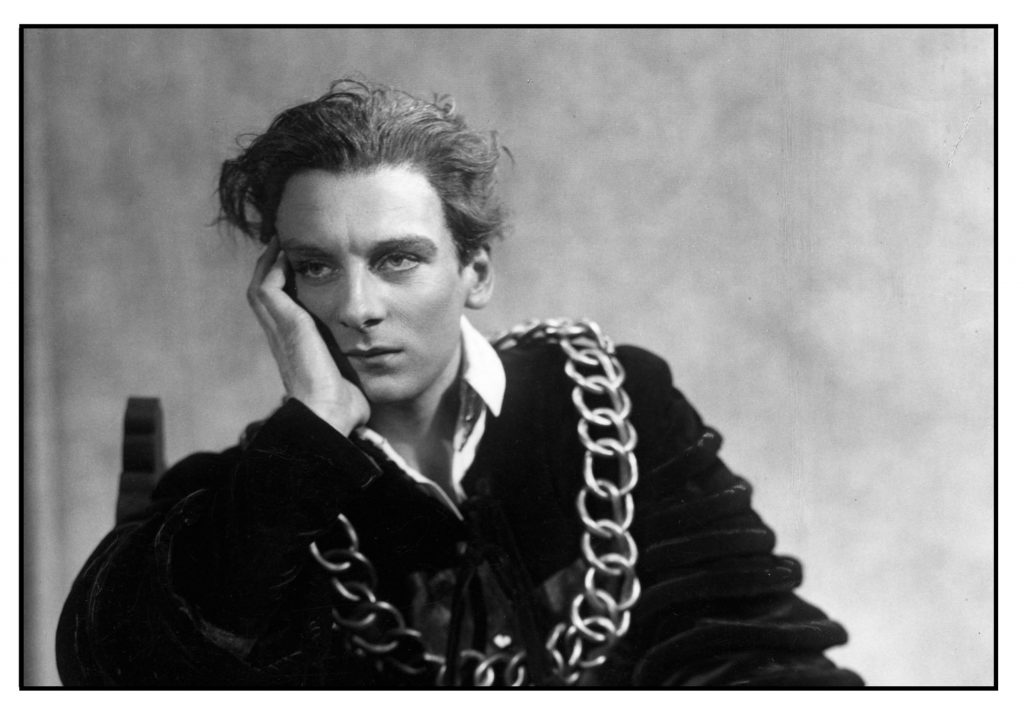

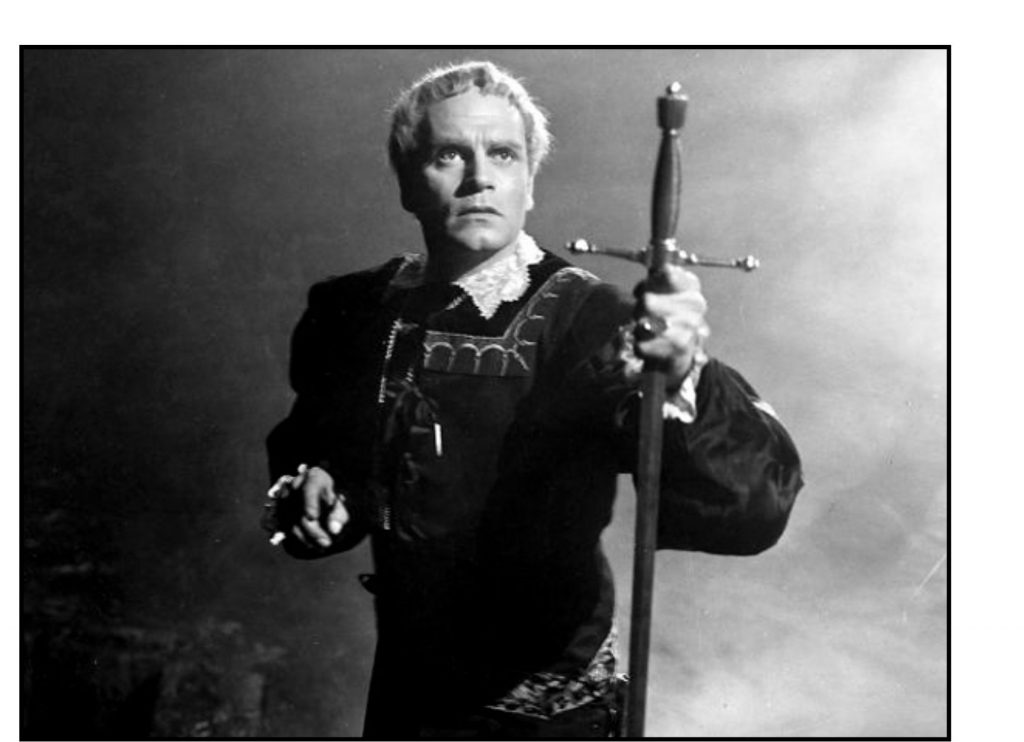

John Gielgud

Sources

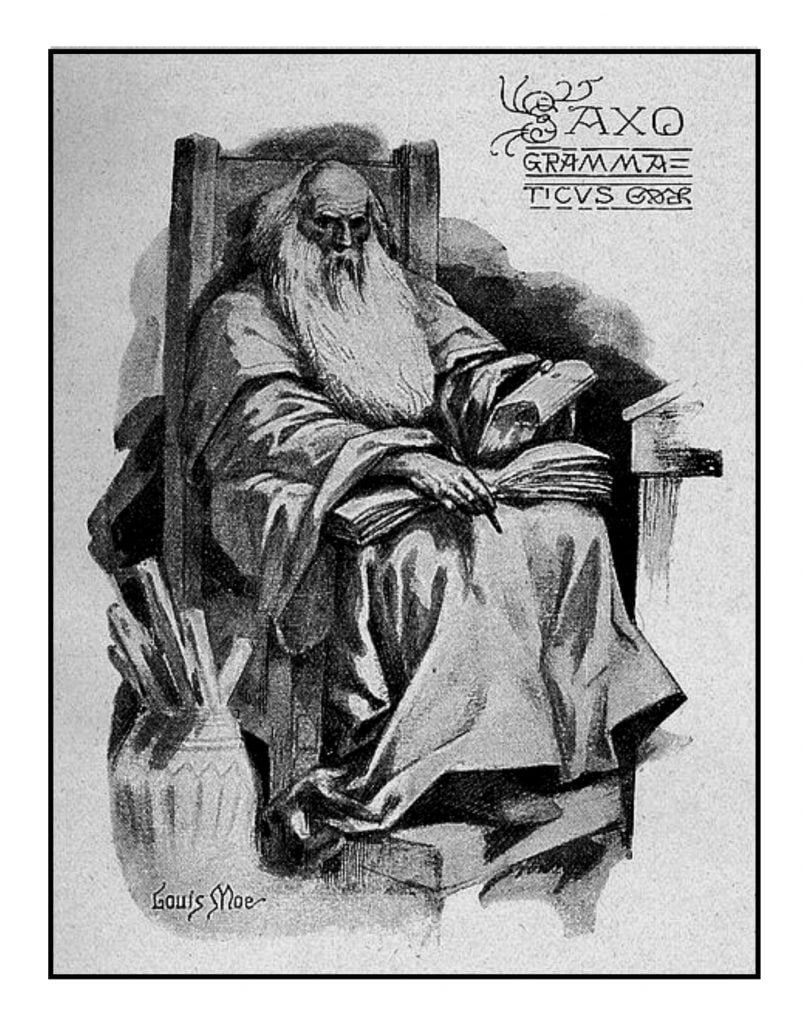

The legend of Hamlet originated in early Scandinavian history (Gollancz, 1926; Jenkins, 1982). The Prose Edda of Iceland briefly mentioned Hamlet in a description of what must have been a huge whirlpool, where nine maidens “in ages past ground Hamlet’s meal” (Gollancz, 1926, p. 1). This reference was interpreted by de Santillana and von Dechend in their 1969 book Hamlet’s Mill as a mythological description of the precession of the equinoxes – the universe rotating round the axis of the whirlpool. This is of little relevance to Shakespeare other than in the idea of divine providence that runs through the play: “The mills of the Gods grind slowly, but exceedingly fine” is not far from

There’s a divinity that shapes our ends

Rough hew them how we will.

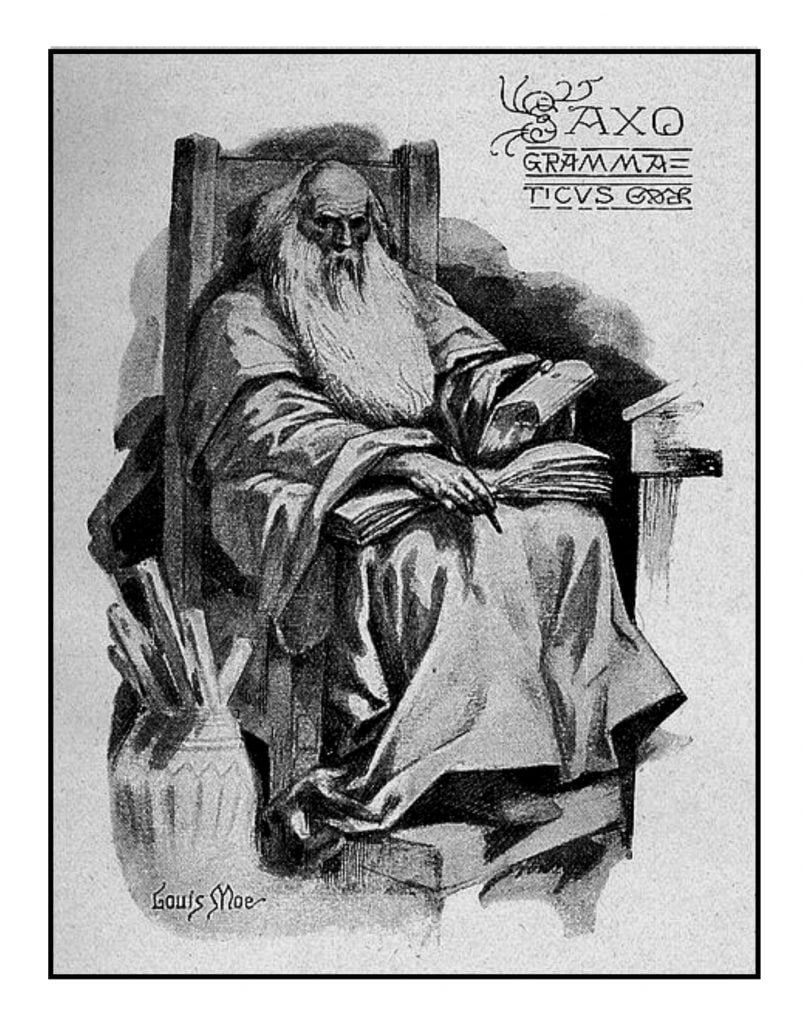

The actual story of Prince Hamlet was first recounted in Latin in Saxo Grammaticus in the Historia Danica (written around 1200 CE). A major part of this story concerns how Hamlet (Amlethus) feigned imbecility so that his uncle, who had murdered Hamlet’s father and married his mother, would not believe that he posed any threat of revenge. Saxo’s story was retold in French by François de Belleforest in his Histoires Tragiques (1570). Shakespeare was likely familiar with this book. Many details of Shakespeare’s play – the murder of Hamlet’s father, the incestuous marriage, Hamlet’s antic disposition, the altered message that leads to the deaths of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern – came from the early sources. The ghost, the players, Ophelia, and the gravedigger were new.

In Shakespeare’s adaptation, not everything makes sense. In the original story, it was common knowledge that Hamlet’s father had been murdered and his throne usurped. Hamlet’s feigned madness served a purpose. In Shakespeare’s play, no one knows that Claudius murdered Hamlet’s father until the Ghost returns and informs his son. As Greenblatt (2004, pp 305-307) points out Hamlet’s antic disposition not only does not provide any protection, but actually calls attention to him.

Shakespeare’s son, born in 1585, was named Hamnet, likely after Hamnet Sadler, one of Shakespeare’s friends in Stratford. However, the name may have caused Shakespeare to read Belleforest. Hamnet Shakespeare died in 1596, while his father was absent in London (Greenblatt, 2004a). Shakespeare’s father John died in September 1601. In James Joyce’s Ulysses, Stephen Dedalus commented on how William Shakespeare likely played the Ghost when Hamlet was first produced in early 1601 (see also Greenblatt, 2004a). In this role he was speaking as though he were his own dead or dying father to his own lost son:

Is it possible that player Shakespeare, a ghost by absence, and in the vesture of buried Denmark, a ghost by death, speaking his own words to his own son’s name (had Hamnet Shakespeare lived he would have been Prince Hamlet’s twin) is it possible, I want to know, or probable that he did not draw or foresee the logical conclusion of those premises: you are the dispossessed son: I am the murdered father: your mother is the guilty queen, Ann Shakespeare, born Hathaway? (Joyce, 1922, Episode 9, Scylla and Charybdis, pp. 186-7)

The ghost is one of the great scenes in the history of the theater. The ghost’s most memorable speech is his description of purgatory.

I am thy father’s spirit,

Doomed for a certain term to walk the night,

And for the day confined to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away.

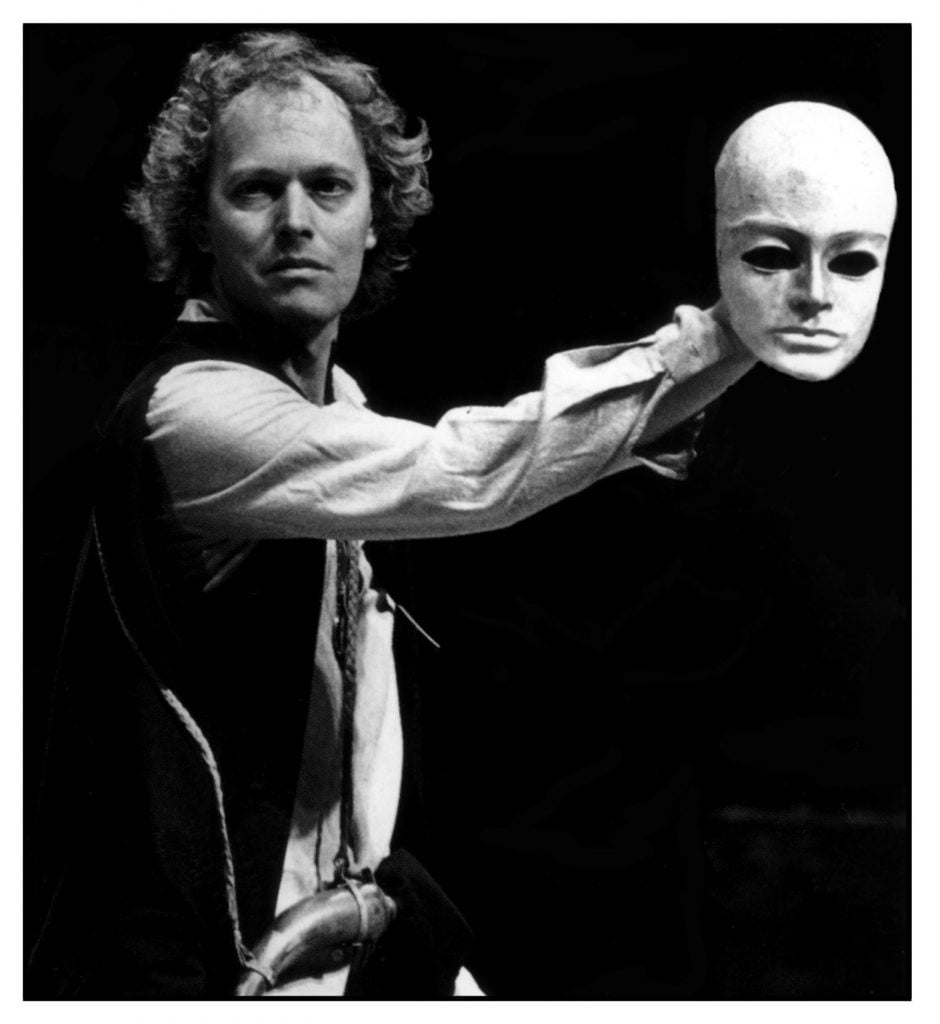

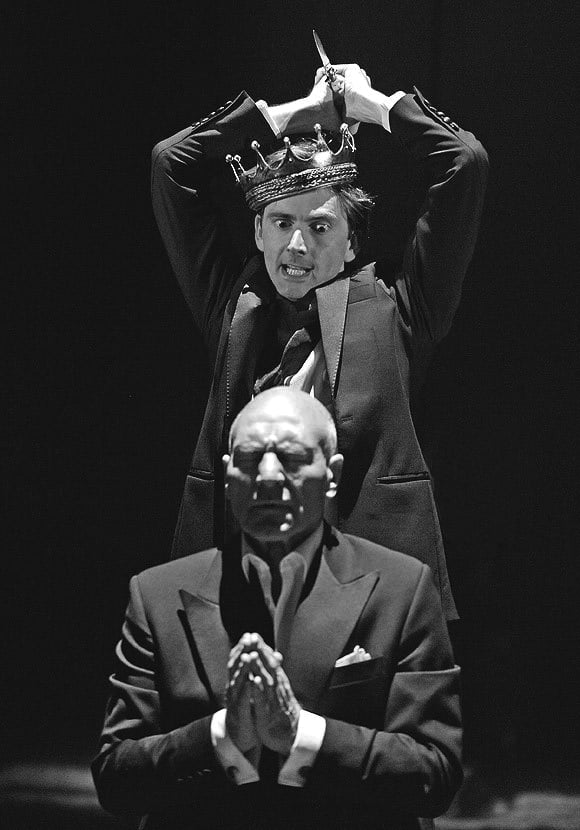

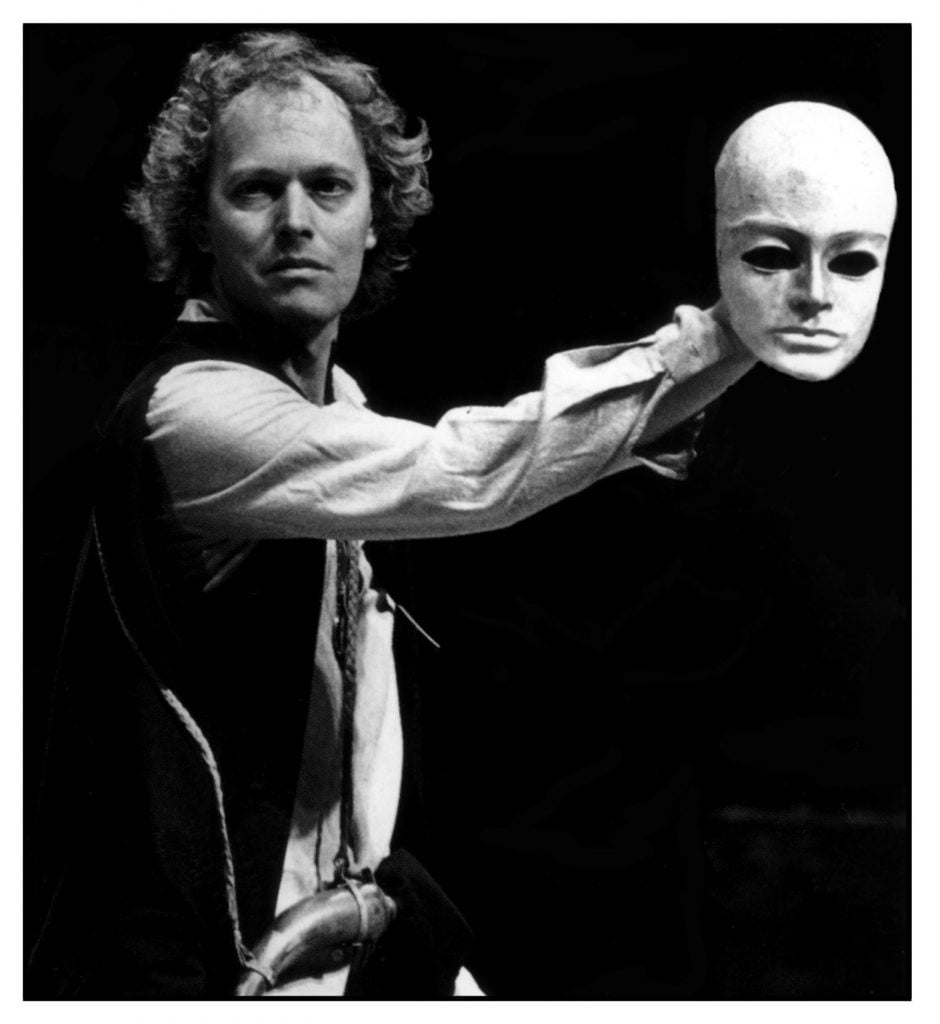

Patrick Stewart

Patrick Stewart

As Greenblatt (2004b) has pointed out, Shakespeare’s father, John Shakespeare, was a likely a covert Catholic, and William was certainly aware of Catholic beliefs, if not himself a practising Catholic. Neither ghosts nor purgatory were acceptable beliefs in the Church of England. Nevertheless, old ideas persist, no matter what the law tells people to believe.

Texts

Shakespeare’s play was likely first performed in early 1601 (Jenkins, 1982; Thompson & Taylor, 2006a). However, another play about Hamlet had been produced on the London stages between 1594 and 1596 and perhaps even earlier. This is often referred to as the Ur-Hamlet. All that we know is that the play contained a ghost that urged Hamlet to revenge. The rest is speculation. Some have attributed this play to Thomas Kyd, who wrote another revenge play called The Spanish Tragedy, and who died in 1594. Others have wondered whether it was actually an early version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, one that he later revised (e.g., Bloom, 1998).

Three early versions of Hamlet were published: by itself in Quarto 1 (1603) and Quarto 2 (1604), and as part of the collected works in Folio 1 (1623) . Quarto 2 and Folio 1 are very similar and the Hamlet text we know today is based on either or both of these versions (Rosenbaum, 2002). Quarto 1 is very different from the other versions: it is much shorter, the scenes occur in a different order, and the poetry is banal. The Quarto 1 version of the most famous speech in the history of the theater:

To be, or not to be – ay, there’s the point.

To die, to sleep – is that all? Ay, all:

No, to sleep, to dream, – ay, marry, there it goes,

For in that dream of death, when we’re awaked

And borne before an everlasting judge,

From whence no passenger ever returned –

The undiscovered country, at whose sight

The happy smile, and the accursed damned.

holds no candle to the one we know:

To be, or not to be – that is the question:

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles,

And by opposing end them; to die: to sleep –

No more, and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to: ’tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished – to die: to sleep –;

To sleep, perchance to dream – ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause

Exactly what this “bad quarto” represents is unknown. It may be the early play (the Ur-Hamlet) by Kyd and/or Shakespeare, a shortened acting version of the play for performance on tour or in small venues, or someone’s reminiscence of a performance published to make quick profit from a popular play. A short German version of Hamlet called Der Bestrafte Brudermord (“Fraticide Punished”) appears to have been performed in Germany in the 17th Century. This is more similar to Quarto 1 than to the other English versions of Hamlet, but it may have been more closely related to the Ur-Hamlet. It has no soliloquies.

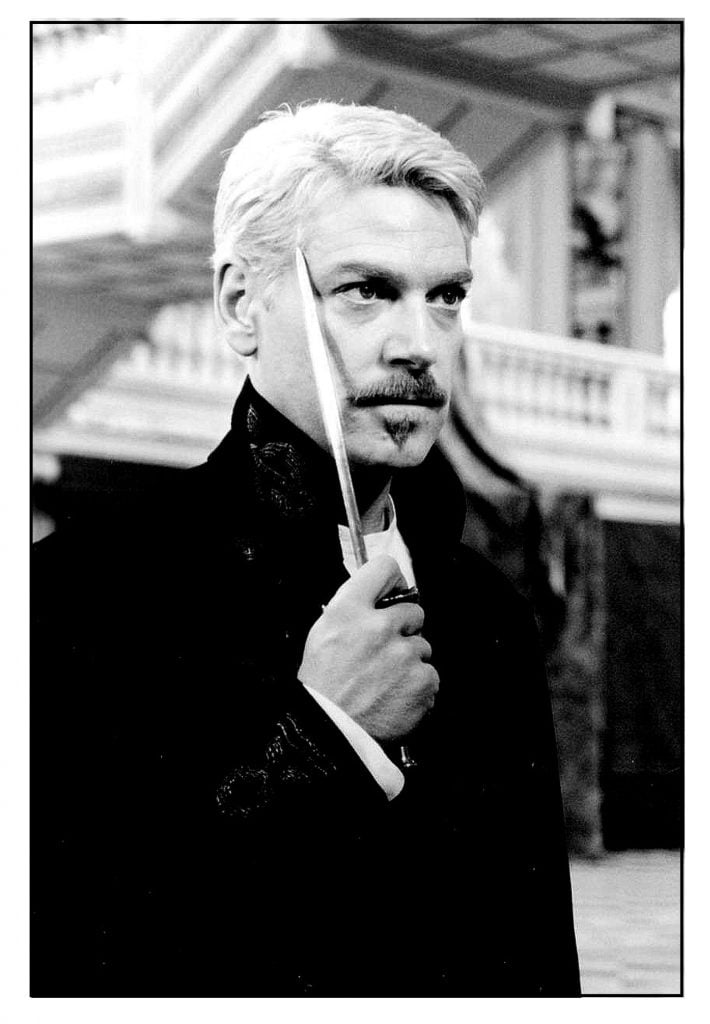

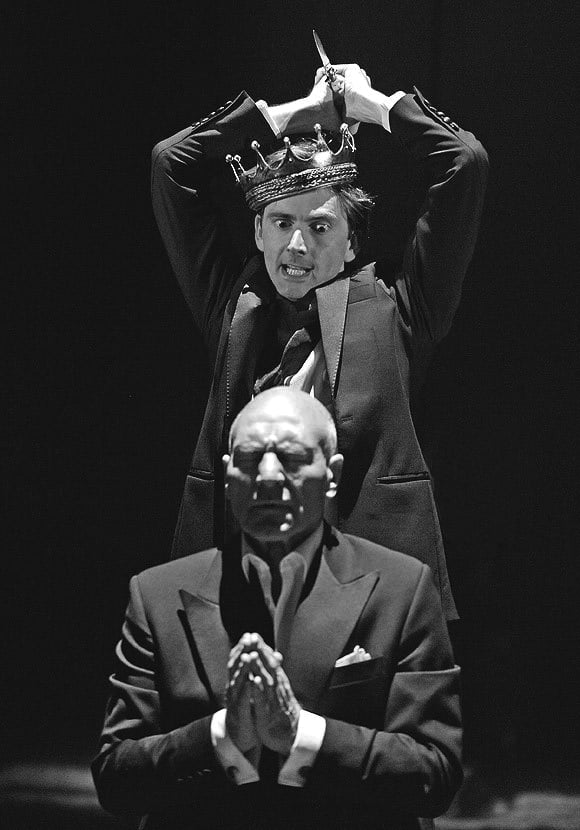

In recent years, several productions of the Quarto 1 Hamlet have been presented (Thompson & Taylor, 2006b). This version of the play is remarkable for its narrative drive. Some aspects of Quarto 1 have also been incorporated into other productions of Hamlet. Most particularly the “To be or not to be” scene is placed before rather than after the arrival of the players and Hamlet’s decision to present The Murder of Gonzago before the king. Gibson (1978, pp. 140-148) provides forceful arguments for this shift of scene. The thoughts in this soliloquy seem incongruous if Hamlet has already decided on a course of action. Gregory Doran’s memorable 1996 Hamlet with David Tennant and Patrick Stewart followed the sequence of Quarto 1.

Pennington (1996) thinks differently, and prefers the usual Quarto 2 sequence. Mott (1904) found that locating this speech after the decision to have the players perform for the king fits with Hamlet’s recurring pattern of resolution followed by inertia (or if you will, of first and second thoughts). Lyndsey Turner’s Hamlet with Benedict Cumberbatch originally moved the soliloquy to the very beginning of the play (as prologue to the action rather than a part of it), but an outcry during previews caused her to move it back.

The Quarto 1 version does not support the idea of Hamlet as someone who vacillates – deciding what to do and then wondering whether this might not be worth it. His actions in Quarto 1 show a clear trajectory toward a purposeful end.

Plays within plays

Hamlet is intensely concerned with the workings of the theater. The first time we see him in Act I, Scene II, Hamlet is concerned by the need to be true to his feelings rather than to play a role. The speech turns on the very idea of what seems and what is true, what is enacted and what is real

These indeed ‘seem,’

For they are actions that a man might play,

But I have that within which passeth show,

These but the trappings and the suits of woe.

Michael Pennington

The play Hamlet comes to a head in Act III, Scene II with a performance before the court of The Murder of Gonzago. This play, which tells a story similar to what actually happened in Denmark, is used successfully to “catch the conscience of the king.”

However, this is not the only piece of theater within the play. When the players first arrive in Denmark, the lead player performs a speech from another play – probably a version of Dido and Aeneas. Christopher Marlowe had written such a play ten years before. However, the speech of the lead player uses words by Shakespeare rather than by Marlowe.

The player’s speech multiplies the levels of imagined reality. The audience watches an actor playing Hamlet as he listens to another actor playing an actor playing Aeneas as he recounts the events of the fall of Troy. The player’s speech presents the gist of Shakespeare’s play – Pyrrhus, the son of the slain Achilles, is taking revenge on the family of Paris, his father’s killer. The moment he is about to slay Priam, father of Paris, he pauses

For lo, his sword,

Which was declining on the milky head

Of reverend Priam, seemed i’ th’air to stick.

So, as a painted tyrant, Pyrrhus stood

And, like a neutral to his will and matter,

Did nothing.

So later will Hamlet pause and forego to kill Claudius.

Priam’s wife, Hecuba, rushes to her husband and her grief brings a tear to the eye of the first player. This leads Hamlet to consider why he is unable to feel even as much as an actor playing a part.

What’s Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,

That he should weep for her? What would he do,

Had he the motive and the cue for passion

That I have? He would drown the stage with tears

And cleave the general ear with horrid speech,

Make mad the guilty and appal the free,

Confound the ignorant, and amaze indeed

The very faculties of eyes and ears. Yet I,

A dull and muddy-mettled rascal, peak,

Like John-a-dreams, unpregnant of my cause,

And can say nothing. No, not for a king

Upon whose property and most dear life

A damned defeat was made.

Triggered by what he has heard and seen, Hamlet decides on a course of action. He will prove the truth of the murder recounted by the Ghost by watching Claudius’ response to the same murder played out on the stage. Theater will be truth’s touchstone.

The meaning of theater within Hamlet can also be consider in another way. Throughout the play, Hamlet decides what he should do by trying out a role within his mind. Acting can be either theatrical or behavioral (or both). Hamlet will allow himself to be moved just like the lead player. Imaginative role-playing is often how we make conscious decisions. We try out the consequences in our mind; then, if the envisioned future fits, we go there. Colin McGinn (2006) finds this an example of the “dramaturgical nature of the self:”

He exemplifies the transition from formless consciousness to personal determinacy, or the closest he can get to that. It is not that Hamlet’s character unfolds during the course of the play, with his “real self” finally revealed by the end; it is rather that he finally succeeds in forging a self from the dramatic materials at his disposal – he finds a part he can play. (p. 48)

The idea of theater pervades the ending of Shakespeare’s play. The dying Hamlet requests Horatio

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story.

Then after Hamlet’s death, as Horatio begins to tell Fortinbras what has happened, it is as if the first presentation of the play Hamlet were beginning:

give order that these bodies

High on a stage be placed to the view,

And let me speak to th’yet unknowing world

How these things came about

…

But let this same be presently performed,

Even while men’s minds are wild; lest more mischance

On plots and errors, happen.

It is impossible not to understand the theatrical connotations of “stage” and “performed.” As Critchley and Webster (2013, p. 226) point out, “Hamlet ends with the promise to perform the tragedy of Hamlet.” Olivier’s 1948 movie began with a brief scene showing Hamlet’s body being borne to a platform high upon the battlements of Elsinore.

Thinking Makes It So

The Renaissance brought back much of the classical literature, and with it a philosophy of life based on humanism rather than theism. Man once again became the measure of all things. This principle originally derived from the Greek Sophist philosopher Protagoras (490-420 BCE). The controversy that it had engendered between relativism and absolutism had during the Middle Ages been clearly resolved in terms of the latter. God determined what was right and man obeyed. Until the Renaissance.

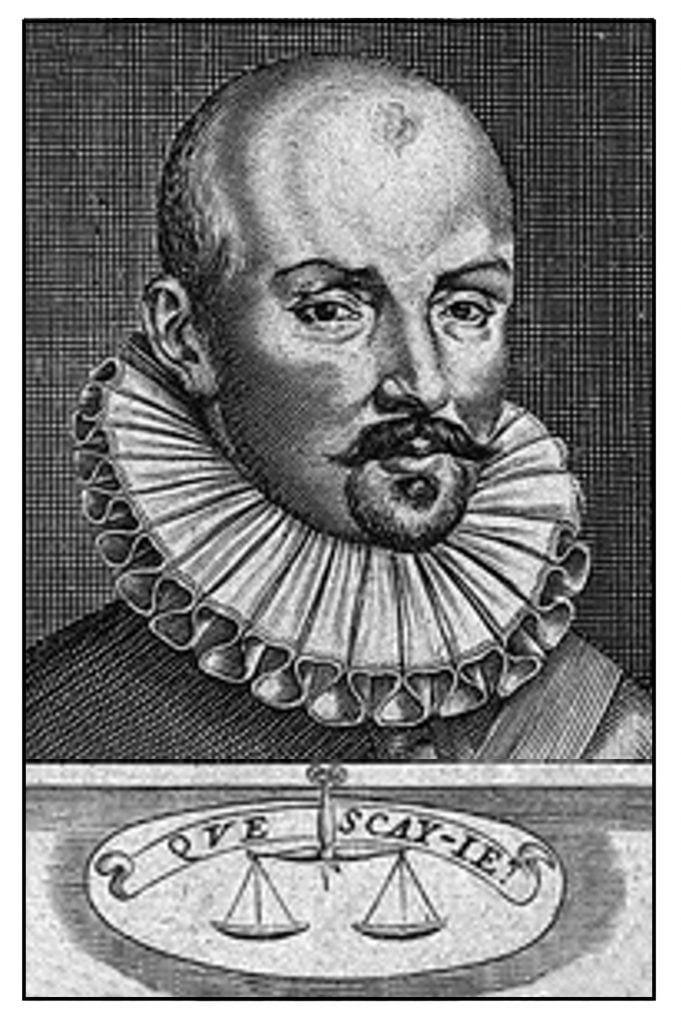

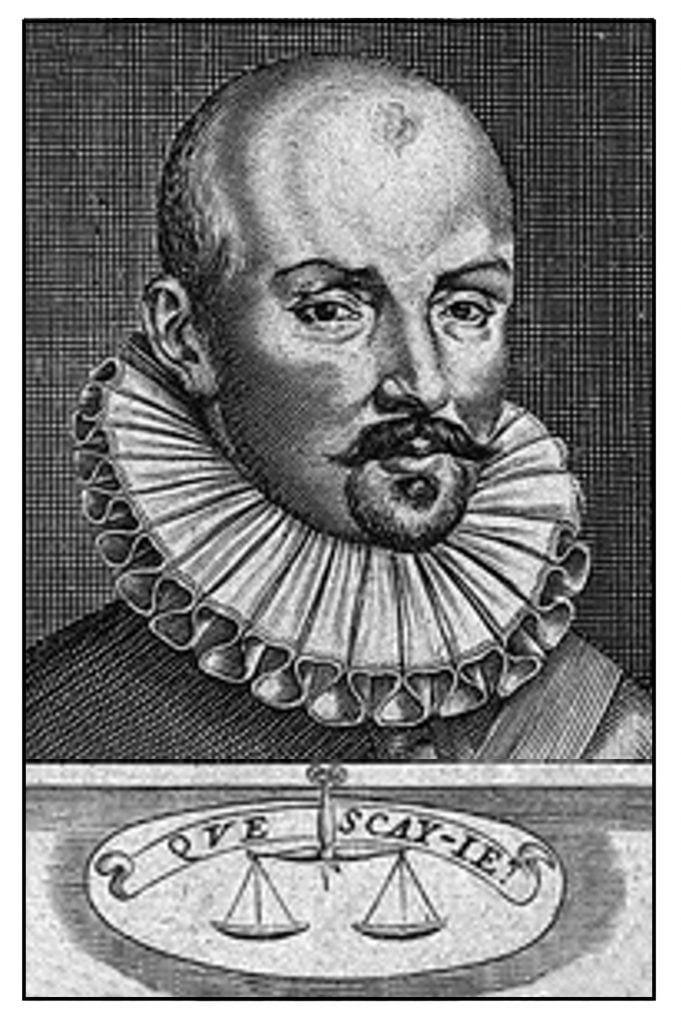

Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) perhaps epitomizes the spirit of the Renaissance (Foglia, 2014). He read widely in the classics but he did not let his erudition stifle the freedom of his thought. His Essays are characterized by a profound humanism and a humble skepticism. He took as his motto the question “Que scay-je?” (What do I know?), and had it engraved on a medal with a weighing-balance. We must always carefully judge what we do and do not know. Montaigne’s essays were translated into English by John Florio and published in 1603.

Shakespeare certainly read Montaigne, probably in the Florio translation, and quoted him extensively in his 1610 play The Tempest. He may also have read some of Florio’s translations prior to their publication, and there are several instances in the 1601 Hamlet that recall the ideas and sometimes the wording of Montaigne (Hooker, 1902). One is Hamlet’s comment to Rosencrantz

for there is nothing

either good or bad, but thinking makes it so

which resonates with

If that which we call evill and torment, be neither torment nor evill, but that our fancie only gives it that qualitie, it is in us to change it. (Florio translation, Volume 2, Book I: Chapter XL That the taste of Goods or Evils doth greatly depend on the opinion we have of them.)

Even more striking are some of the parallels between “To be or not to be” and

Death may peradventure be a thing indifferent, happily a thing desirable. Yet is it to bee beleeved, that if it be a transmigration from one place to another, there is some amendement in going to live with so many worthy famous persons, that are deceased ; and be exempted from having any more to doe with wicked and corrupted Judges. If it be a consummation of ones being, it is also an amendement and entrance into a long and quiet night. Wee finde nothing so sweete in life, as a quiet rest and gentle sleepe, and without dreames. (Florio translation, Volume 5, Book III: Chapter XII Of Physiognomy)

In his lecture of Hamlet, Rossiter (1961, p. 186), suggested that Hamlet is “the first modern man.” What or who is modern clearly varies with what is being considered past and present. However, Rossiter is correct to consider Hamlet as modern rather than as medieval. Hamlet makes his own judgments about what he should do and calls into question all that he has been taught or told. Shakespeare allows the audience to follow his thinking through the soliloquies and asides that occur throughout the play. More so than ever before, we become privy to the thoughts of a person as he works through his motivations, doubts and fears. Hamlet follows the advice of Montaigne

It is no part of a well-grounded judgement simply to judge ourselves by our exterior actions: A man must thorowly sound himselfe, and dive into his heart, and there see by what wards or springs the motions stirre. (II: I Of the Inconstancie of our Actions)

In the soliloquies we can watch as Hamlet proceeds from despair to resolution. He is working things out for himself; he is not following the rules. Hamlet thinks and acts more like a human being than a hero.

Dalkey (1981) presents a tongue-in-cheek analysis of the “To be or not to be” speech using the principles of modern decision-analysis. Hamlet weighs the costs and benefits and comes up with the best course of action. The decision is to be. But then Hamlet also analyses how he came to this decision and wonders whether too much thinking actually has a negative effect on action.

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprises of great pith and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

Hamlet is also aware of other difficulties. Even though we might decide how to act, we may not always maintain our resolution to act, and, even if we do, we cannot fully control the outcome of our actions. During The Murder of Gonzago, the player King responds to his wife’s insistence that she will not remarry when he dies

I do believe you think what now you speak;

But what we do determine, oft we break.

Purpose is but the slave to memory,

Of violent birth but poor validity,

Which now, the fruit unripe, sticks on the tree

But fall unshaken when they mellow be.

…

Our wills and fates do so contrary run

That our devices still are overthrown.

Our thoughts are ours, their ends none of our own

Bloom (1998, p 424) wonders whether this speech may have represented the lines that Hamlet asked to be inserted in the original play. The speech is likely intended for his mother, who may have become unwittingly entrammeled in Claudius’ evil.

Being

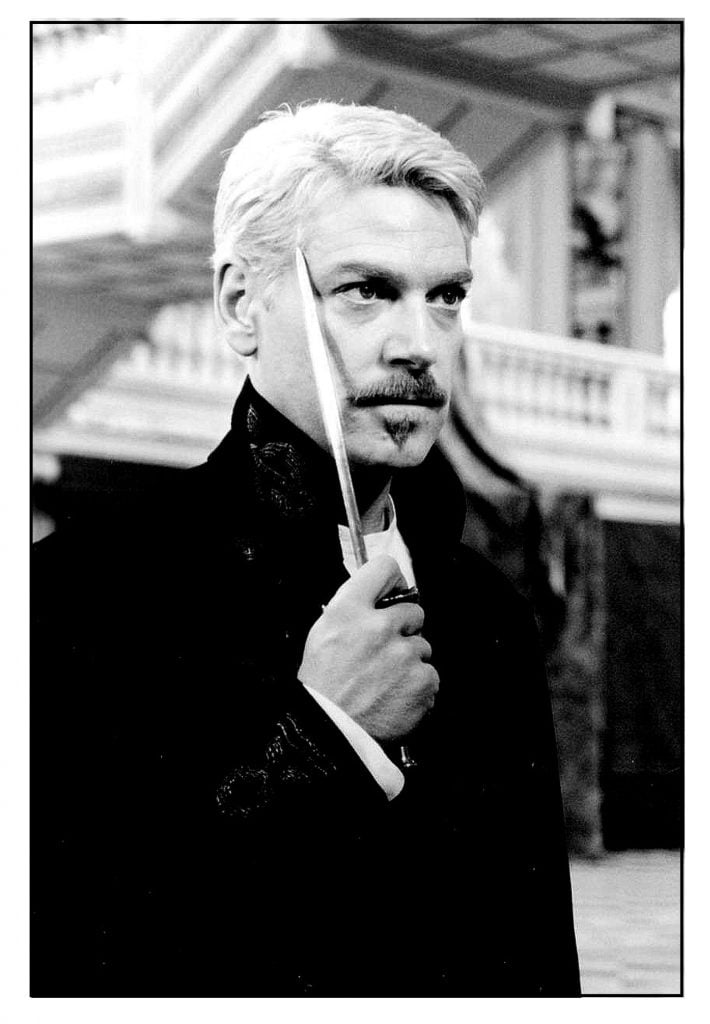

Kenneth Branagh

“To be or not to be” is the most famous speech in all literature. Hamlet is considering the essential problem of being human – how to act in a life often characterized by suffering and always leading to death. His words portray “the exaltation of mind … as this grandest of consciousnesses overhears its own cognitive music” (Bloom, 2003, p 36).

Yet the speech has been interpreted in many different ways (summarised by Petronella, 1974, and Jenkins, 1982, pp 484-493). A common interpretation is that Hamlet is deciding whether or not to commit suicide (e.g., Bradley, 1905; Knight, 1935, p 127):

He is meditating on suicide; and he finds that what stands in the way of it, and counterbalances its infinite attraction, is not any thought of a sacred unaccomplished duty, but the doubt, quite irrelevant to that issue, whether it is not ignoble in the mind to end its misery, and, still more, whether death would end it. (Bradley, 1905, p 132).

However, the actual words seem far more generalized. As Pennington (1996, p. 81) points out

There is no personal pronoun at all in its thirty-five lines, so it is in a sense drained of Hamlet himself: although the cap fits, it also stands free of him as pure human analysis.

The speech can therefore be considered as a meditation on the human condition:

The question, then (crudely paraphrased as ‘Is life worth living?’) is essentially whether, in the light of what being comprises (in the condition of human life as the speaker sees it and represents it in what follows) it is preferable to have it or not. (Jenkins, 1982, p 487).

A third approach to Hamlet’s speech relates it to Hamlet’s decision to revenge his father’s death. What is to be or not to be is the act of killing Claudius. Hamlet’s decision revolves upon whether this is right or not, given that one may in the afterlife be damned by sin:

Thus the complete development of the soliloquy shows that the full implication of “To be, or not to be” is not a simple choice between passive endurance and vitally destructive activity, as at first appears, a choice that Hamlet, who has no fear of death itself, could make unhesitatingly; but that the choice is rather between a distasteful passive endurance and a destructive activity that may also bring the stain of deadly sin. (Richards, 1933, p. 757).

This interpretation may fit with the mention of “conscience” and “resolution” at the end of the speech. However, it does not really ring true with Hamlet’s view of the afterlife, which he simply describes as “undiscover’d.”

Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscover’d country from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Hamlet does not fear eternal damnation, he is just uncertain about whether the afterlife might indeed be worse than the present life. He is skeptical about what he has been taught. In those days, being from Wittenberg was probably akin to being from Missouri in our day.

A final interpretation turns on the fact that Hamlet’s speech is not a soliloquy. Hamlet is being overheard by Claudius and Polonius. If Hamlet is also aware of this, as well he might be, then the speech may be part of his efforts to convince Claudius that he is not a threat. Hamlet may be feigning both melancholy thoughts of suicide and a total lack of resolution.

Hamlet pretends to speak to himself but actually intends the speech itself or an account of it to reach the ears of Claudius in order to mislead his enemy about his state of mind. (Hirsh, 2010, p 34)

However, if Hamlet were indeed feigning, he would likely have been far more illogical in his thinking. His words convey more poetic insight than antic disposition.

So I think that Hamlet in this speech is indeed considering the human condition. The habit of his mind is to interprets the events of the moment according to eternal principles. The student from Wittenberg is an inveterate philosopher. Hamlet’s meditation on the skull of Yorick shows a similar way of thinking..

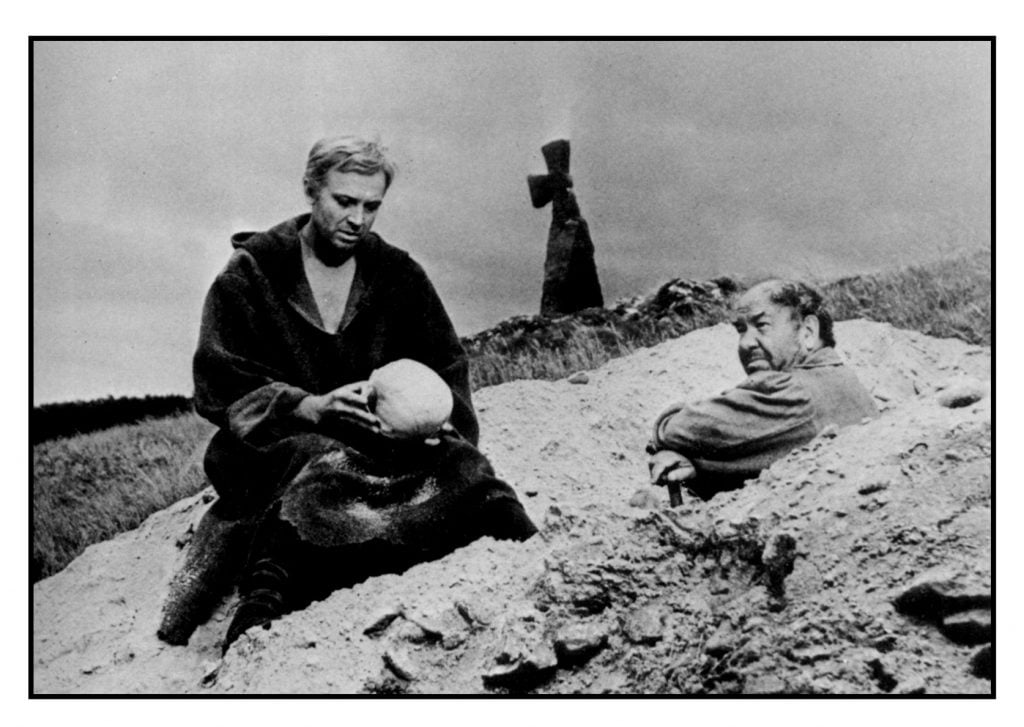

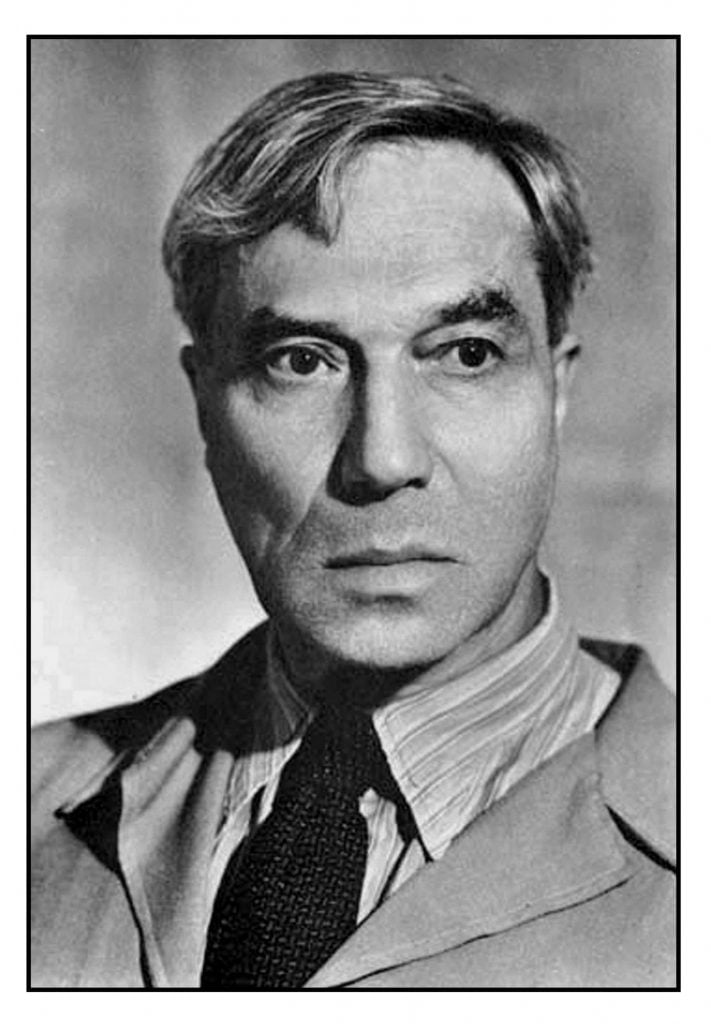

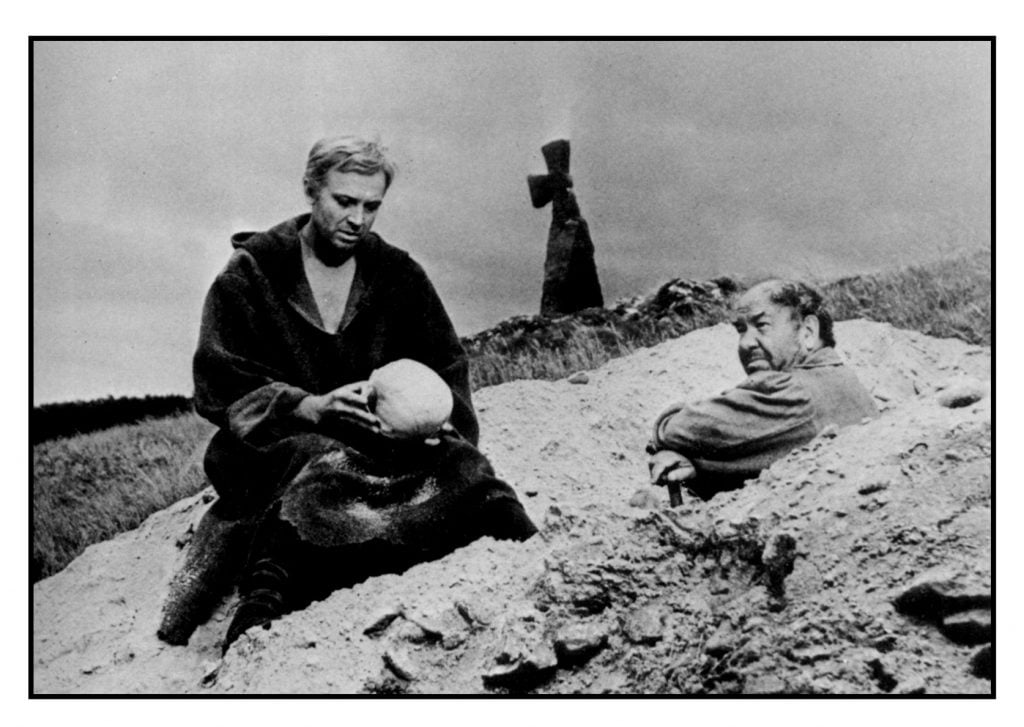

Innokenti Smoktunovsky in Kozintsev’s Movie

Revenge Delayed

One common view of Hamlet is that he cannot move from thought to action. He is unable to take revenge on Claudius because he worries too much about his motives and the consequences. This was the interpretation of Samuel Taylor Coleridge in a lecture given in 1819:

In Hamlet he [Shakespeare] seems to have wished to exemplify the moral necessity of a due balance between our attention to the objects of our senses, and our meditation on the workings of our minds,—an equilibrium between the real and the imaginary worlds. In Hamlet this balance is disturbed: his thoughts, and the images of his fancy, are far more vivid than his actual perceptions, and his very perceptions, instantly passing through the medium of his contemplations, acquire, as they pass, a form and a colour not naturally their own. Hence we see a great, an almost enormous, intellectual activity, and a proportionate aversion to real action, consequent upon it, with all its symptoms and accompanying qualities. This character Shakespeare places in circumstances, under which it is obliged to act on the spur of the moment:—Hamlet is brave and careless of death; but he vacillates from sensibility, and procrastinates from thought, and loses the power of action in the energy of resolve. (Coleridge, 1907, pp 136-137)

A variant of this interpretation is that Hamlet is too sensitive and inward to cope with the rough needs of the external world. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe gives this idea to his character Wilhelm Meister, who focuses on Hamlet’s words at the end of Act I and senses that the prince cannot cope with the demands made by his ghostly father:

The time is out of joint: O cursed spite,

That ever I was born to set it right!

In these words, I imagine, will be found the key to Hamlet’s whole procedure. To me it is clear that Shakespeare meant, in the present case, to represent the effects of a great action laid upon a soul unfit for the performance of it. In this view the whole piece seems to me to be composed. There is an oak-tree planted in a costly jar, which should have borne only pleasant flowers in its bosom; the roots expand, the jar is shivered.

A lovely, pure, noble, and most moral nature, without the strength of nerve which forms a hero, sinks beneath a burden which it cannot bear and must not cast away. All duties are holy for him; the present is too hard. Impossibilities have been required of him, not in themselves impossibilities, but such for him. He winds, and turns, and torments himself; he advances and recoils; is ever put in mind, ever puts himself in mind; at last does all but lose his purpose from his thoughts; yet still without recovering his peace of mind. (Goethe, 1796, Book IV Chapter 13, pp 304-5)

Yet de Grazia (2007) points out that Hamlet’s procrastination only became a major part of the critical literature after the late 18th Century. Before then no one had mentioned the delay let alone made it the touchstone of the play. There is a clear trajectory linking the death of Hamlet’s father, the apparition of the Ghost, the decision of Hamlet to test the Ghost’s claim by putting on a play that represents the murder, and Hamlet’s conclusion that Claudius is indeed guilty. Hamlet is not lacking in will: he simply subjects it to careful scrutiny.

A brief pause occurs during the “To be or not to be” soliloquy and, as previously mentioned, even that might be solved by placing it in the order of the First Quarto: before rather than after the players arrive. Or by considering it as a moment of philosophical reflection prior to an already determined action.

David Tennant and Patrick Stewart

The major source of the supposed delay occurs when Hamlet comes upon the solitary Claudius at prayer – “Now might I do it pat …” Yet Hamlet worries that he might send the repentant Claudius to Heaven, and does it not:

Up, sword, and know thou a more horrid hent:

When he is drunk asleep, or in his rage,

Or in the incestuous pleasure of his bed;

At gaming, a-swearing, or about some act

That has no relish of salvation in’t;

Then trip him, that his heels may kick at heaven,

And that his soul may be as damn’d and black

As hell, whereto it goes. (Act III: Scene 3)

This speech was often considered shocking. Many of the audience could not accept that Hamlet really meant to send Claudius to eternal damnation. De Grazia (2007, p 159) quotes Samuel Johnson who considered the speech “too horrible to be read or to be uttered.” Human justice could take away the mortal life, but should not damn the soul to everlasting perdition.

Hamlet’s desire in the prayer scene to damn a soul to eternal pain is the most extreme form of evil imaginable in a society that gave even its most heinous felons the opportunity to repent before execution. (De Grazia, 2007, p. 188)

De Grazia reviews the various ways we have tried to reconcile our romantic concept of Hamlet as a sweet and thoughtful prince with this terrible speech. A simple way is to state that Hamlet does not really mean what he is saying. Finding himself unable to kill Claudius, he comes up with a plausible excuse for delaying his revenge. Another view might be that the speech is a way for Hamlet’s consciousness to prevent the deep hatred in his unconsciousness from taking control of his actions. He subdues the unconscious with a rationalization that revenge will be better at another time. In either of these interpretations, Hamlet is deceiving himself.

Hamlet certainly practises deception. He puts “an antic disposition on” to convince Claudius that he is too foolish to be considered dangerous. Yet Hamlet does not deceive himself. In his soliloquies he seeks to understand what he should do. He looks for reasons, not for rationalizations.

So I think we should take Hamlet’s speech about damning Claudius at face-value. Hamlet is not kind; he cruelly rejects Ophelia; he rashly kills Polonius; he has no sympathy for his mother; he callously sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to their deaths. There is a harshness rather than a gentleness at his core. De Grazia even wonders whether there is something demonic about Hamlet in the latter parts of the play. Perhaps Shakespeare is demonstrating that even the most self-reflective of heroes is not immune to cruelty. Hamlet cannot stop the general corruption in Denmark without becoming infected by its evil.

Hamlet does ultimately take his revenge. Claudius has no time for repentance. And Hamlet dies, victim of the evil that he has fought against.

Tragedy

A pervasive idea is that tragedy results from the downfall and death of a great man that is mainly due to a moral defect in his character – the “tragic flaw.” This concept derived from Aristotle’s proposal that the key to tragedy was hamartia. However, the Greek word means “missing the mark” – an error or failing that may or may not be related to the tragic hero (Golden, 1978). In the Greek New Testament hamartia was translated as “sin,” in the sense of general failure rather specific wrongdoing.

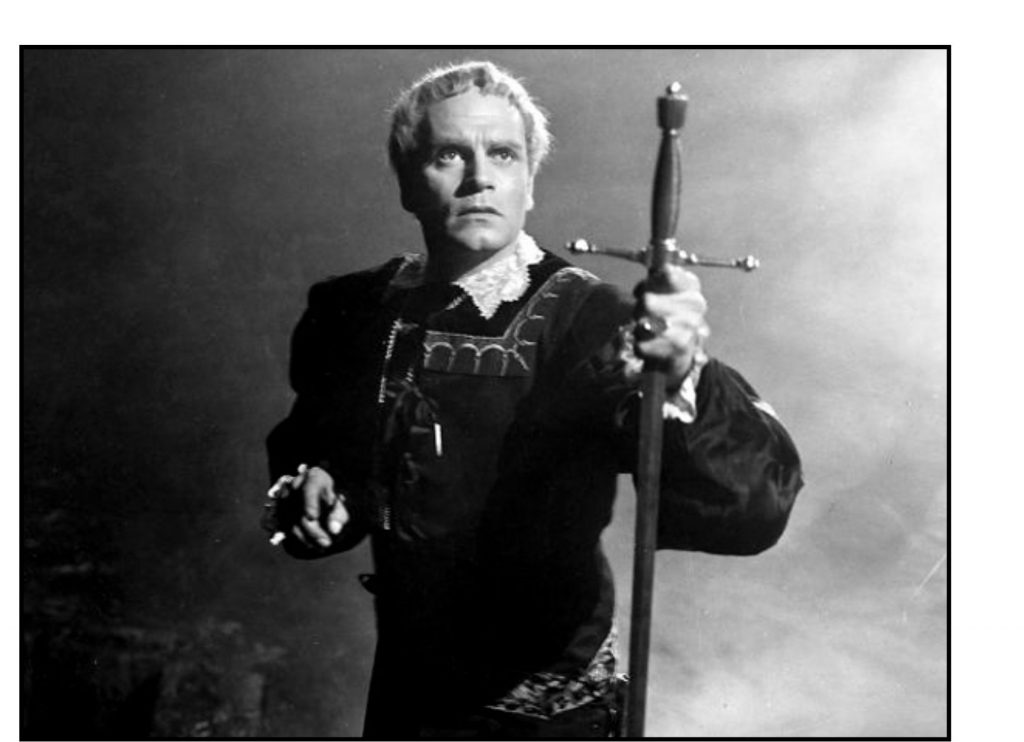

Laurence Olivier

The concept of the tragic flaw may not be helpful in understanding Hamlet. To consider the hero’s flaw as the mainspring of the tragedy “leads to a narrowing of scope and significance which is stultifying and crippling” (Hyde, 1963). Perhaps the most outrageous example of stupid simplification is the voice-over at the beginning of Laurence Olivier’s 1948 film: “This is the tragedy of a man who could not make up his mind.” This was completely out of keeping not only with Shakespeare’s play but also with Olivier’s portrayal, which showed Hamlet as decisive and active.

Although Bradley (1905) supported the idea of the tragic flaw as the key to tragedy, he also perceived other contributing factors. In particular “men may start a course of events but can neither calculate nor control it” (p. 9). We may be unable to predict what happens when we decide to act. This sounds very similar to the true meaning of hamartia: we may miss the mark.

Kitto (1960) proposed that Hamlet shows many similarities to the classic Greek tragedies. Like them, Shakespeare’s play has characteristics of a religious drama. The corruption of Claudius infects everyone. Gertrude is seduced; Polonius becomes Claudius’ spy; Ophelia is convinced to act as bait for so that Hamlet may be spied upon; Laertes is co-opted to the murder of Hamlet. “Something is rotten in the state of Denmark” and needs to be cleansed away:

[T]here is an overruling Providence which, though it will not intervene to save Hamlet, does intervene to defeat Claudius, and does guide events to a consummation in which evil frustrates itself, even though it destroys innocents by the way. (Kitto, 1960, p 321).

Hamlet considers the actions of Providence at the beginning of the play’s final scene. As well as telling Horatio of the “divinity that shapes our ends,” Hamlet decides to engage in the proposed duel with Laertes despite his forebodings:

We defy augury: there is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be, ’tis not to come. If it be not to come, it will be now. If it be not now, yet it will come. The readiness is all, since no man of aught he leaves knows what is’t to leave betimes. Let be.

These comments can be understood in two ways. Hamlet may be recognizing that he cannot fully control what happens, and that he must believe that what will happen will be good. Or perhaps Hamlet is losing his nerve, giving up control and letting events unfold without him.

By the end of the play those attainted with corruption have died, and a new government is in place in Denmark. Unfortunately, Providence has not really provided for those who were most innocent, such as Ophelia, or those who began in innocence, such as Hamlet. Providence may work for the general good but it is not specially concerned with individuals. Sparrows die.

Shakespeare differs from the Greeks in questioning that all is necessarily for the good. At the end of the play, Denmark has been freed from Claudius, but we are far from sure that country under Fortinbras will be a better place.

Nevertheless, Hamlet demonstrates the need to rid society of corruption, regardless of the personal cost. This need is general to all human societies. We should not stand by and let evil spread:

Hamlet is a tocsin that awakens the conscience. (Kozintsev, 1966, p 174)

The real tragedy of Hamlet is that Denmark did not make him king. Denmark settled for Claudius, and wound up with Fortinbras. Shakespeare explains this clearly in the final speech of the play:

Let four captains

Bear Hamlet like a soldier to the stage,

For he was likely, had he been put on,

To have prov’d most royal

Envoi

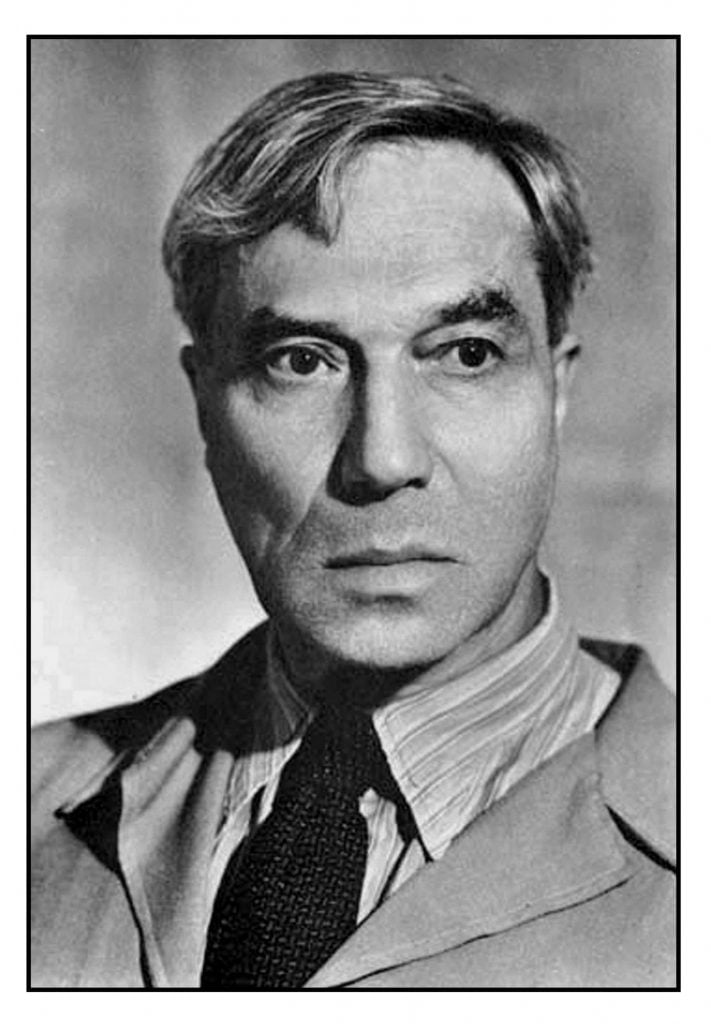

Boris Pasternak

Hamlet has become a part of our life. In a sense we all play this role. We may not face the same problems that Hamlet encountered. Yet we each have our own decisions to make, and their outcomes will prove some mixture of what we will to occur and what happens nevertheless. Boris Pasternak’s character Doctor Zhivago wrote a poem about playing Hamlet. Here again are many levels: Pasternak conceives of Zhivago who writes a poem about an actor playing Hamlet. This poem was recited at Pasternak’s funeral despite government efforts to prevent any eulogies (Ivinskaya, 1978, p 331). The superb translation is by Ann Pasternak Slater, the novelist’s niece.

The murmurs ebb; onto the stage I enter.

I am trying, standing in the door,

To discover in the distant echoes

What the coming years may hold in store.

The nocturnal darkness with a thousand

Binoculars is focused onto me.

Take away this cup, O Abba, Father,

Everything is possible to thee.

I am fond of this thy stubborn project,

And to play my part I am content.

But another drama is in progress,

And, this once, O let me be exempt.

But the plan of action is determined,

And the end irrevocably sealed.

I am alone; all round me drowns in falsehood:

Life is not a walk across a field.

Russia in the time of Stalin was strikingly similar to Denmark in the time of Claudius. Violence pervaded all society; everyone was under surveillance. Pasternak translated Hamlet into Russian in 1939, at a time of the Great Terror when he was unable to write poetry. His translation was used for the 1964 Kozintsev movie of the play. Pasternak’s view was that Hamlet took on the “role of judge in his own time and servant of the future” (Pasternak, 1959, p 131). This was Hamlet’s legacy.

References

Bradley, A. C. (1905/1961). Shakespearean tragedy: Lectures on Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, Macbeth. London: Macmillan. Available at arkiv.org

Bloom, H. (1998). Shakespeare: The invention of the human. New York: Riverhead Books.

Bloom, H. (2003). Hamlet: Poem unlimited. New York: Riverhead Books.

Coleridge, S. T. (1907). Coleridge’s essays & lectures on Shakespeare: & some other old poets & dramatists. London: J.M. Dent. Available

Critchley, S., & Webster, J. (2013). Stay, illusion! The Hamlet doctrine. New York: Pantheon Books (Random House).

Dalkey, N. C. (1981). A case study of a decision analysis: Hamlet’s soliloquy. Interfaces, 11(5), 45-49.

Dorani, G. (1996/2010) Hamlet. Royal Shakespeare Company. Warner Home Video.

Foglia, M. (2014) Michel de Montaigne, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Gibson, W. (1978). Shakespeare’s game. New York: Atheneum.

von Goethe, J. W. (1796, translated by T. Carlyle, 1824, reprinted 1901). Wilhelm Meister’s apprenticeship. Boston: F.A. Niccolls & Co.

Golden, L. (1978). Hamartia, ate, and Oedipus. Classical World, 72, 3–12.

Gollancz, I. (1926). The sources of Hamlet with an essay on the legend. London: Oxford University Press.

De Grazia. M. (2007). Hamlet without Hamlet. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Greenblatt, S. (2004a). The death of Hamnet and the making of Hamlet. N.Y. Review of Books, (21 October 2004) 51.16.

Greenblatt, S. (2004b). Will in the world: How Shakespeare became Shakespeare. New York: Norton.

Hirsh, J. (2010). The “To be, or not to be” speech: evidence, conventional wisdom, and the editing of “Hamlet.” Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England, 23, 34-62.

Hooker, E. R. (1902). The relation of Shakespeare to Montaigne. Publications of the Modern Language Association (PMLA), 17, 312-366.

Hyde, I. (1963). The tragic flaw: is it a tragic error? Modern Language Review, 58, 321-325.

Ivinskaya, O. (translated by M. Hayward, 1978). A captive of time: my years with Pasternak London: Collins & Harvill.

Jenkins, H. (Ed.) (1982/2003). Shakespeare, W. Hamlet. London: Arden Shakespeare.

Joyce, J. (1922/1946). Ulysses. New York: Random House.

Kitto, H. D. F. (1960). Form and meaning in drama: A study of six Greek plays and of Hamlet. London: Methuen.

Kozintsev, G. M. (1964/2006). Hamlet. Facets Video.

Kozintsev, G. M. (translated by J. Vining, 1966).Shakespeare; time and conscience. New York: Hill and Wang.

McGinn, C. (2006). Shakespeare’s philosophy: Discovering the meaning behind the plays. New York: HarperCollins.

de Montaigne, M. (1580-83, translated by J. Florio, 1603/1891). Essayes. Volumes 1-6 London: Gibbings. Available at Internet Archive: Vol 2, Vol 3 and Vol 6 are quoted.

Olivier, L. (1948/2006). Hamlet. Criterion Collection. (Text used in the movie is documented in Olivier, L., Furse, R., & Shakespeare, W. (1948). Hamlet. London: B. Pollock.)

Pasternak, B. L. (1959). I remember: Sketch for an autobiography. New York: Pantheon (includes an essay on Translating Shakespeare).

Pennington, M. (1996). Hamlet: a user’s guide. London: Nick Hern Books.

Petronella, V. F. (1974). Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy: Once more unto the breach. Studies in Philology, 71, 72-88.

Richards, I. T. (1933). The meaning of Hamlet’s Soliloquy Publications of the Modern Language Association (PMLA), 48, 741-766.

Rosenbaum, R. (2002). Shakespeare in rewrite. New Yorker. (13 May, 2002) 68-77.

Rossiter, A. P. (Ed. G. Storey, 1962). Angel with horns and other Shakespeare lectures. London: Longmans.

de Santillana, G., & von Dechend, H. (1969). Hamlet’s mill; an essay on myth and the frame of time. Boston: Gambit.

Thompson, A., & Taylor, N. (Eds.) (2006a). Shakespeare, W. Hamlet. London: Arden Shakespeare.

Thompson, A., & Taylor, N. (Eds.) (2006b). Shakespeare, W. Hamlet: The texts of 1603 and 1623. London: Arden Shakespeare.

Wilson, J. D. (1935). What happens in Hamlet. Cambridge, U. K.: University Press.