Charlie Hebdo

Charlie Hebdo

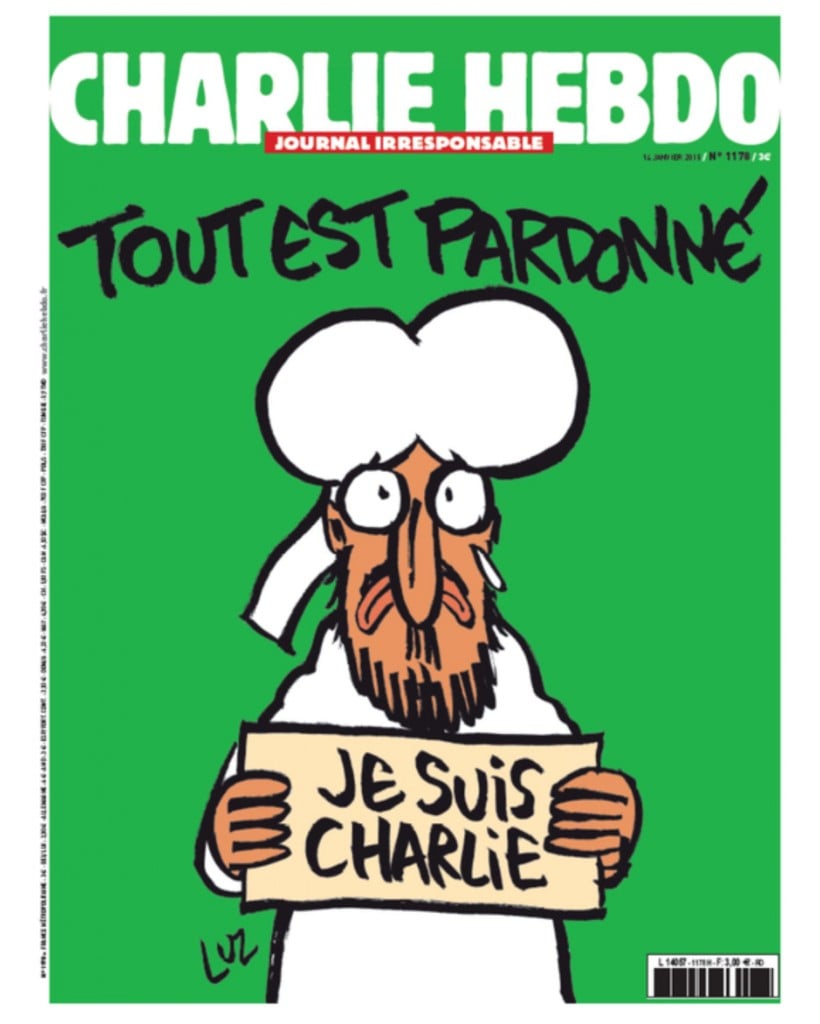

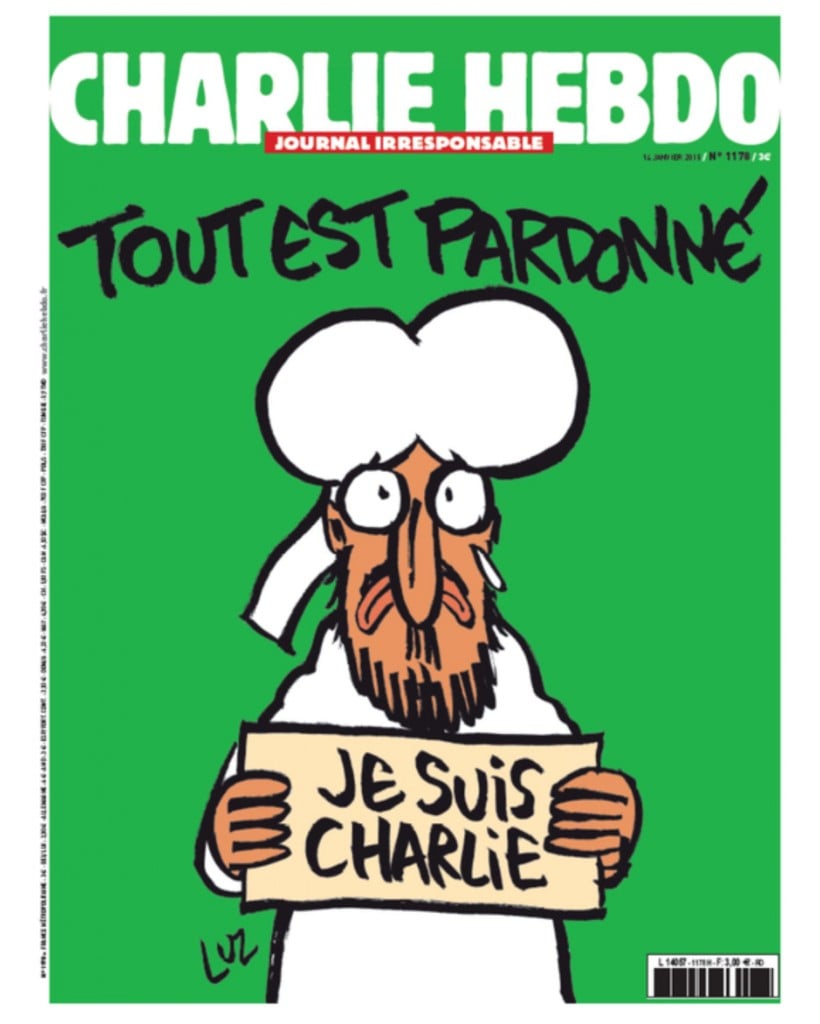

A great outpouring of sympathy and solidarity followed the assassination of the editorial staff at Charlie Hebdo. A million people gathered in Paris in silent protest. The motto Je suis Charlie was promoted across the world. The magazine refused to restrain its irreverence. The cover of its first issue after the attack showed the Prophet forgiving the blasphemy against him (Tout est pardonné) and supporting Je suis Charlie.

Nevertheless, most Western newspapers did not reprint either this cover or the earlier cartoons that had precipitated the assassinations. Their rationale was that these would unnecessarily offend those who believe that any depiction of the Prophet is sacrilegious. For example, despite the opposition of some of its own journalists, the Toronto Star decided not to publish the cartoons:

We could run the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. There is a strong news rationale for doing so. But there are important reasons of principle not to do it. Just as we would not publish racist or pornographic images, we will exercise our judgment not to print the cartoons.

We will not print them because we have too much respect for fellow Canadians of Muslim background. We will not send a message that their way of being Canadian is less acceptable or less valuable than that of any other citizen. (Cruikshank, 2015).

The opposing viewpoint is that the act of terrorism itself justifies the further publication of the offending material. Otherwise we would be submitting to censorship by intimidation rather than by principle:

If a large enough group of someones is willing to kill you for saying something, then it’s something that almost certainly needs to be said, because otherwise the violent have veto power over liberal civilization, and when that scenario obtains it isn’t really a liberal civilization any more. (Douthat, 2015)

As the weeks passed, there has also been some acknowledgment of the offence (e.g. Tariq Ali, 2015). Not that this could in any way justify the violence. Just that in a civil society one should respect the beliefs of others. Not to do so, particularly when the others are in a minority, is to demean them. It is far better to mock those in power than those without.

Furthermore, the vaunted freedom to satirize the beliefs and actions of Muslims is clearly out of balance with the strict limitations placed on any criticism of Jewish beliefs or history. It is far easier to defame that Prophet than to deny the Holocaust.

Rights and Limitations

The right of free speech has been championed by many authors. The basic concept is that all people should be able to express themselves freely, because only in this way will society be able to discover what is true and right. The freedom must be granted even if the opinions expressed are considered to be offensive or untrue. In the end, truth will win:

And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously by licencing and prohibiting to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse, in a free and open encounter. (Milton, 1644).

The basic right of free expression is listed as Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948):

Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers.

Nevertheless, liberty cannot survive without limitations. John Stuart Mill acknowledged that our freedom to act as we see fit must be curtailed if it causes harm to others:

the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others (Mill, 1864, p. 22).

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, 1960, Article 19.3) therefore grants that freedom of expression might be restricted in order to respect the “rights and reputations of others” or to protect “national security, public order, public health or morals.” The restrictions are sometimes difficult to interpret. One should not slander another person, divulge national secrets, incite riots, or spread disease. Yet what are the limits that protect the morals of society?

Pornography and Censorship

Although the main subject of this post is whether or not blasphemy should be limited, I shall briefly discuss another area wherein freedom of expression comes into conflict with morality. How should a society govern the publication and consumption of pornography? I shall use the term “pornography” to mean sexually explicit material without making any judgment of its value, i. e., I shall not distinguish between erotica and pornography (West, 2012).

Most Western countries no longer prohibit pornography. With the internet, pornography has become widely available. The general feeling is that its private consumption should not be regulated. Nevertheless, society still maintains some clear and absolute limits. Pornography with children is considered illegal. This is a clear case where exercise of freedom causes severe harm. No child should be exploited in such a way. Some have suggested that adult pornography also exploits the actors who participate in its production. Yet adult actors can provide consent, and other means of legal recourse outside of censorship are available if consent is not obtained.

A major feminist criticism of pornography is that it portrays women as objects rather than persons and thereby infringes on their rights (e.g., MacKinnon, 1987, p. 148):

Pornography, in the feminist view, is a form of forced sex, a practice of sexual politics, an institution of gender inequality. In this perspective, pornography is not harmless fantasy or a corrupt and confused misrepresentation of an otherwise natural and healthy sexuality. Along with the rape and the prostitution in which it participates, pornography institutionalizes the sexuality of male supremacy, which fuses the erotization of dominance and submission with the social construction of male and female.

In this way, pornography may demean all women, diminish their rights, and promote sexual violence. However, pornography comes in many varieties, and there is little definite evidence in Western societies that the increased consumption of pornography over the last few years has either decreased the social status of women or increased the violence against them.

If one views pornography across the world rather than just in the West, there is even less evidence that pornography limits the rights of women. States where censorship is so severe that pornography is unavailable are often those in which women have the least rights (Coetzee, 1996, p. 81). Further studies of the sociological and psychological effects of the different types of pornography are needed. Yet in the meantime, it is probably best not to increase limits. We know so little about the scope of sexual feelings, and art is one way to investigate the nature and limits of human desire.

Another consideration is that pornography certainly causes “offence” even it is claimed to be harmless. Feinberg (1985) has proposed that freedom of expression might be limited in cases where it is not directly harmful but simply offensive. The problem is to define what is meant by “offence” (Shoemaker, 2000; Dacey, 2012, pp. 74-81; van Mill, 2012). A simplistic distinction would consider harm as more physical and offence as more mental. However it is also possible to consider both along a single dimension, with offence tending to be less traumatic.

Offence can take the form of disgust, shock, resentment, shame, repulsion, embarrassment, fear, or humiliation. The offending actions or objects are considered “obscene,” a term that perhaps derives from the Latin caenum for filth. Most countries have laws against obscenity, though their usage varies.

One general principle that has been accepted for pornography is that offence should not be relevant if it need not be experienced. Though a person may be offended by the idea that pornography is freely available on the internet, this should not be considered reason for censorship since the person need not force himself or herself to be offended by viewing the material.

Obscenity laws prohibit the public display or advertisement of pornographic images. Similarly a person is not allowed to walk around naked in public or to defecate in the street. Almost everyone would agree with such regulations. A less justifiable example prohibits public broadcasters from using words such as “fuck” and “shit” (Shoemaker, 2000). Offence and obscenity are usually judged on the basis of majority views. However, this often comes down to the most vocal of the offended, and may not take into account the sensibilities of minorities.

Somehow society must determine some reasonable course to prevent unnecessary offence while still protecting the right to free expression. Judgments as to what is offensive should be especially fair. One group of persons should not be able to enforce their sensibilities more than another.

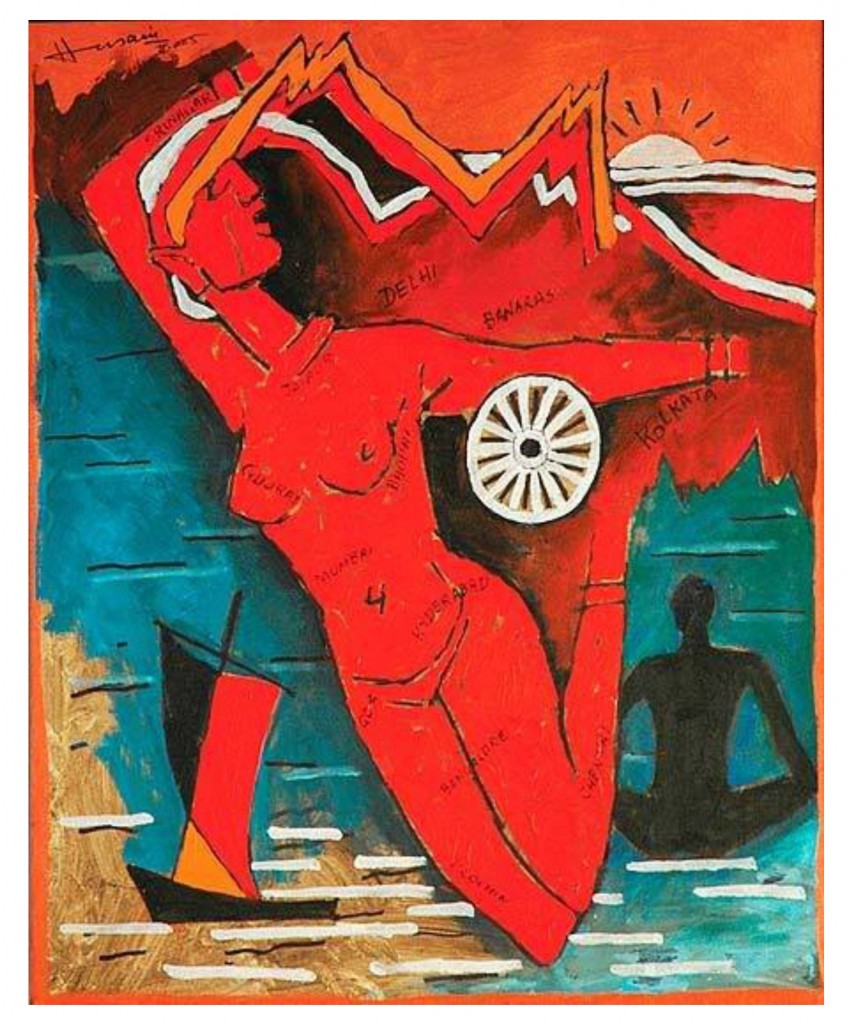

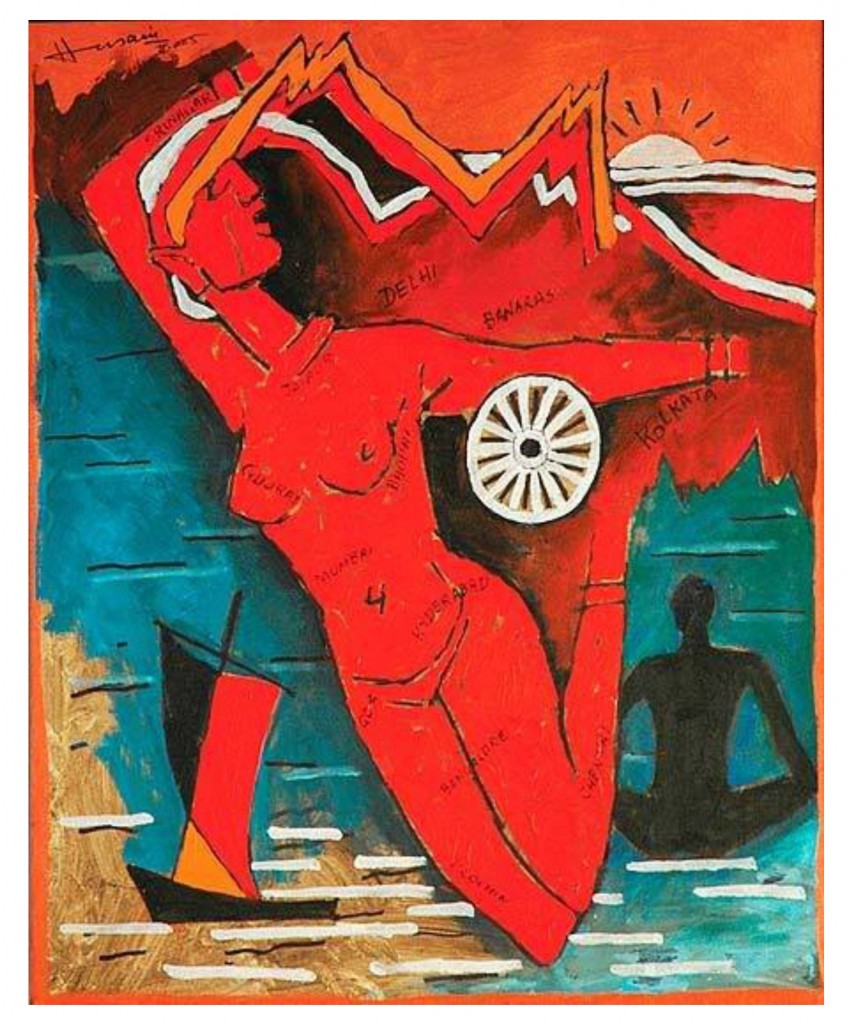

The injustice of allowing anyone to take offence and declare something obscene is illustrated in the case of Maqbool Fida Husain, a famous Indian painter and film director of Muslim origin. In 2006, the 90-year old artist was charged with obscenity for paintings Hindu Goddesses in the nude. Particularly singled out was his painting of Bharatmata (Mother India) illustrated on the left. The painting shows a nude women posed in the outline of India. In the center is the Ashoka Chakra (the wheel of Ashoka, an Indian emperor from the 3rd century BCE, who converted to Buddhism). This wheel, representing the law of dharma, is also represented in the Indian flag.

The injustice of allowing anyone to take offence and declare something obscene is illustrated in the case of Maqbool Fida Husain, a famous Indian painter and film director of Muslim origin. In 2006, the 90-year old artist was charged with obscenity for paintings Hindu Goddesses in the nude. Particularly singled out was his painting of Bharatmata (Mother India) illustrated on the left. The painting shows a nude women posed in the outline of India. In the center is the Ashoka Chakra (the wheel of Ashoka, an Indian emperor from the 3rd century BCE, who converted to Buddhism). This wheel, representing the law of dharma, is also represented in the Indian flag.

Multiple warrants were issued for Husain’s arrest. Having decided that it would be impossible to defend himself, Husain left India and lived in self-imposed exile in Qatar. It is difficult to view the charges against him other than in the context of anti-Muslim bigotry. The alleged offences were even more bizarre in light of the long history of Hindu erotic sculpture. In 2008, the Delhi High Court dismissed all charges against Husain and castigated the Puritanism of his accusers. However, Husain never returned to India. He died in London in 2011.

Blasphemy

For a religious person, blasphemy can cause far greater offence than pornography. In the past, severe punishments were meted out for taking the name of God in vain:

And he that blasphemeth the name of the Lord, he shall surely be put to death, and all the congregation shall certainly stone him: as well the stranger, as he that is born in the land, when he blasphemeth the name of the Lord, shall be put to death. (Leviticus 24:16).

If God were truly omnipotent, He or She would be completely unaffected by any blasphemy. The God of the Old Testament must have been both “thin-skinned and short-tempered” (Dacey, 2012, p. 18).

Although the word “blasphemy” was originally concerned with speech and with the name of God, it has come to mean any expression that holds up to mockery or contempt things held as sacred by others. “Defamation of religion” is the term most commonly used nowadays.

The UN resolution against the defamation of religions was affirmed by a majority of voters but many Western countries voted against the resolution or abstained (United Nations, 2008). They detected some hypocrisy in countries that wished to make religion sacrosanct, and yet persecuted individuals for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and of religion. In some Islamic countries, individuals can be executed for blasphemy or apostasy. A major reason for human rights legislation is to defend those without power to defend themselves. Making it a sacrilege to criticize religion easily leads to the tyranny of the majority religion.

Another argument is that making religious beliefs above criticism is discriminatory against those that are skeptical about such beliefs. Why should it be right for the religious to chastise the behavior of the secular and not vice versa?

Yet, we all take offence when something we hold dear or sacred is treated with contempt. Such offences are not always experienced in the context of religion. As Pope Francis said after the Charlie Hebdo assassinations, many people object to someone calling their mother names. People also take great offence at the desecration of their national flag, and many countries have laws against this. Patriotism is often as unthinking as religion. Belief in “my country right or wrong” has a decidedly religious ring to it.

Hate Speech

Although many Western countries still have laws against blasphemy, they tend not to be prosecuted. For example, a theater in Sault St. Marie in Canada was charged in 1980 with blasphemous libel for showing Monty Python’s Life of Brian, but the charges were stayed (Walkom, 2015).

Most cases that would have been treated as blasphemy in the past are now considered under the rubric of “hate speech” (van Mill, 2012). Many countries have laws prohibiting the incitement of people to hate others on the base of race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion. Typically the laws concern public speech and do not cover private conversations or internet chat-rooms. Often the laws require that there is clear and immediate danger to the group against which the invective is expressed.

Charlie Hebdo was charged with hate speech after it re-published the Danish cartoons in 2005.The trial led to the magazine being acquitted in 2007 since the cartoons were not deemed hateful of all persons of Muslim origin but only those with terrorist persuasions.

In Canada, James Keegstra was convicted of hate speech in 1984 for teaching in school that a Jewish conspiracy had distorted history for hundreds of years and invented the Holocaust. The point of the trial was that he thereby instilled a hatred of Jewish people in his students (Mertl & Ward, 1986). Although it might be acceptable under the right to free expression to deny the Holocaust, it seems clearly wrong to teach this to children as accepted fact. Yet, the school board had terminated Keegstra’s teaching contract before he was indicted for “wilfully promoting hatred” against Jews. Was the trial really necessary? It was a complex case: the conviction was overturned on appeal and then re-instated by the Supreme Court of Canada.

Hate speech is wrong. However, outside of cases when a mob is harangued to violence against a group of people on the basis of race, religion or sexual orientation, or when people are specifically incited to commit murder or mayhem, or when children are indoctrinated with hatred rather than taught tolerance, it is difficult to see clearly how to set the legal limits to freedom of expression.

Society should provide some support for views that are not those of the majority. Sometimes the majority is wrong and the minority should have its say. As Milton said, the truth will be victorious if given free rein in the field of opinion. In relation to religion, surely skepticism must be tolerated. Beliefs can be criticized while still protecting the individuals that hold those beliefs. Agnès Callamard (2005) has proposed that any restriction on free speech should itself be clearly limited:

Restrictions must be formulated in a way that makes clear that its sole purpose is to protect individuals holding specific beliefs or opinions, rather than to protect belief systems from criticism. The right to freedom of expression implies that it should be possible to scrutinise, openly debate, and criticise, even harshly and unreasonably, belief systems, opinions, and institutions, as long as this does not amount to advocating hatred against an individual.

Fairness

One of the principles whereby one might set limits to freedom of speech is that of fairness. Each group of persons that may be offended by the free speech of another group should be treated equally.

In this context, the argument can easily be made that Islam and Judaism are not treated equally in relation to defamation. Criticism of Judaism is much less tolerated than mockery of Islam. Part of this has to do with the Holocaust. The world recognizes the horrors entailed by anti-Semitism, and wants to eliminate any chance of these recurring (Altman, 2012).

However, should not the same privileges be granted to the religion of Islam? Does not the mockery of Islam support violent actions against Islamic countries? Over the past century, Islamic countries have been invaded and their peoples subjugated. The rights of Islamic peoples in many countries have been subject to tyrants maintained in power by the West.

A rights-based argument against the mockery of the Prophet can be formulated in much the same way as the feminist argument against pornography. Pornography may limit the rights of female persons by encouraging the general view that they are objects of desire and domination rather than individual persons. Submitting the beliefs of Muslims to continuous ridicule may likewise limit their civil rights by encouraging the idea that they are all ignorant fools with dangerous ideas.

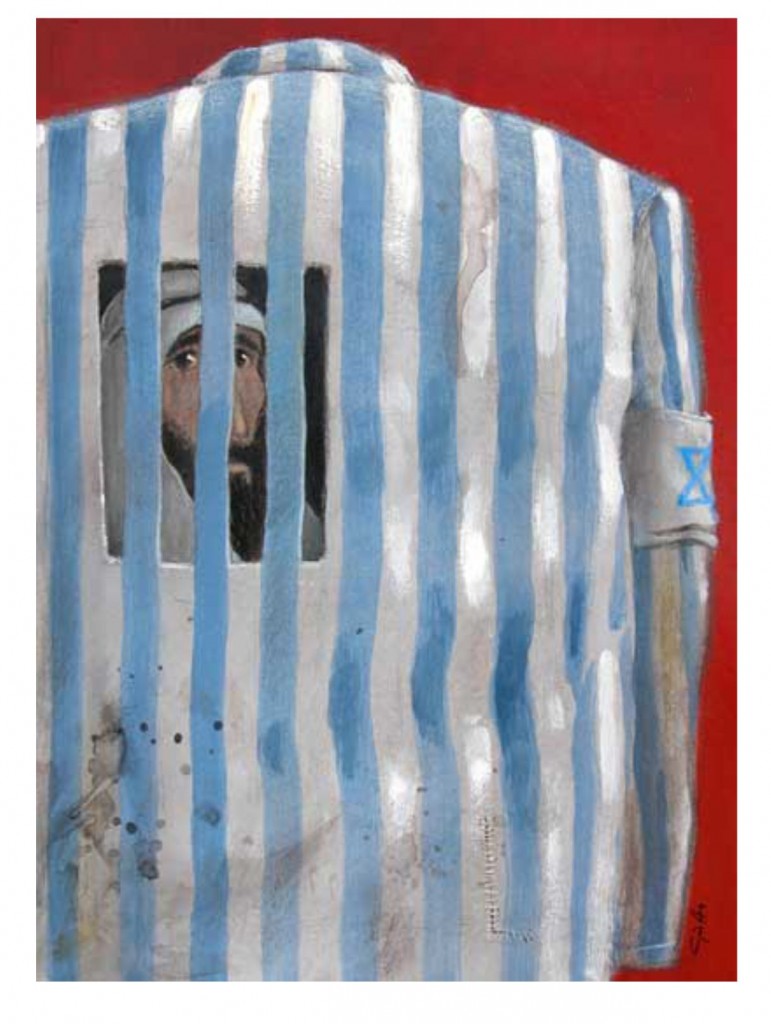

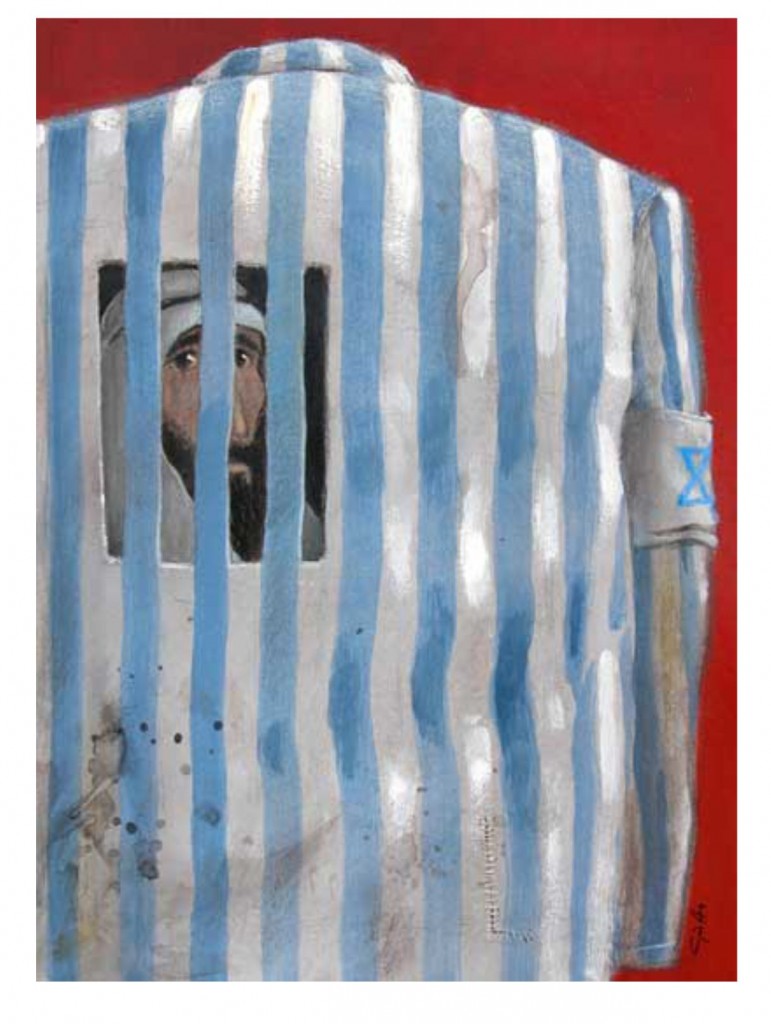

After the controversy of the Danish cartoons in 2005, the Iranian newspaper Hamshahri sponsored the International Holocaust Cartoon Contest to denounce Western hypocrisy on freedom of speech. The topic of the Holocaust was chosen as it was deemed as offensive to Judaism as depiction of the Prophet was to Islam. The contest did not cause much controversy and some of the cartoons were republished in Western newspapers. The main theme of many of the cartoons was the way that Israel used the Holocaust to deflect any criticism of its denial of human rights to Palestinians in the occupied territories. On the left is the entry of Alessandro Gatto, an Italian cartoonist.

After the controversy of the Danish cartoons in 2005, the Iranian newspaper Hamshahri sponsored the International Holocaust Cartoon Contest to denounce Western hypocrisy on freedom of speech. The topic of the Holocaust was chosen as it was deemed as offensive to Judaism as depiction of the Prophet was to Islam. The contest did not cause much controversy and some of the cartoons were republished in Western newspapers. The main theme of many of the cartoons was the way that Israel used the Holocaust to deflect any criticism of its denial of human rights to Palestinians in the occupied territories. On the left is the entry of Alessandro Gatto, an Italian cartoonist.

Multiple Rights

Though Muslim countries have proposed that human rights legislation include provisions against the defamation of religion (United Nations, 1990, 2008), they have been highly selective in their response to the right of religious freedom as proposed in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations. 1948):

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

In some Islamic countries, blasphemy and apostasy are considered punishable by death. Freedom of religion in relation to Islam does not always recognize of the “freedom to change his religion or belief.”

However, the West has also been selective in its support of human rights (Mayer, 2006). The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (United Nations, 1966) differs from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by asserting as its first article:

All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

This striking change came about in relation to the overthrow of European colonialism and the coming into being of new governments in Asian and African countries (Mayer 2006).

The Invasion of Iraq was a flagrant denial of the right to self-determination. In addition, Guantanamo and other prisons operated by the Western powers against Islamic people are a terrible rejection of the right to be free from torture (Article 5 of the Universal Declaration and Article 7 of the Covenant). The overwhelming hypocrisy is that these rights were denied in order to bring freedom and democracy to the benighted peoples of the Middle East.

The concept of human rights is multifaceted. Freedom of expression is just one of many rights. Others are equally important. Every person should have the right to work, education, and security. Many of these rights are not readily available to minorities within Western countries. Mockery or their beliefs simply compounds their sense of disenfranchisement.

Perhaps if all rights were equally available, freedom of expression would cause less offence. The rich and powerful are less harmed by mockery than the poor and powerless.

In 1993 the World Conference on Human Rights proposed that

All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated. The international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis. While the significance of national and regional particularities and various historical, cultural and religious backgrounds must be borne in mind, it is the duty of States, regardless of their political, economic and cultural systems, to promote and protect all human rights and fundamental freedoms. (United Nations, 1993)

Perhaps we should work harder to give all members of our society all their rights – the full spectrum not just the ones we cherish most. Freedom of speech could then be used to enlighten rather than demean, acting as a gadfly rather than a bludgeon.

Should religion not be defamed?

In the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo assassinations, religious leaders both deplored the murders and called for society not to defame religious beliefs. The argument is that such defamation demeans and marginalizes those with sincere beliefs and promotes violent retribution.

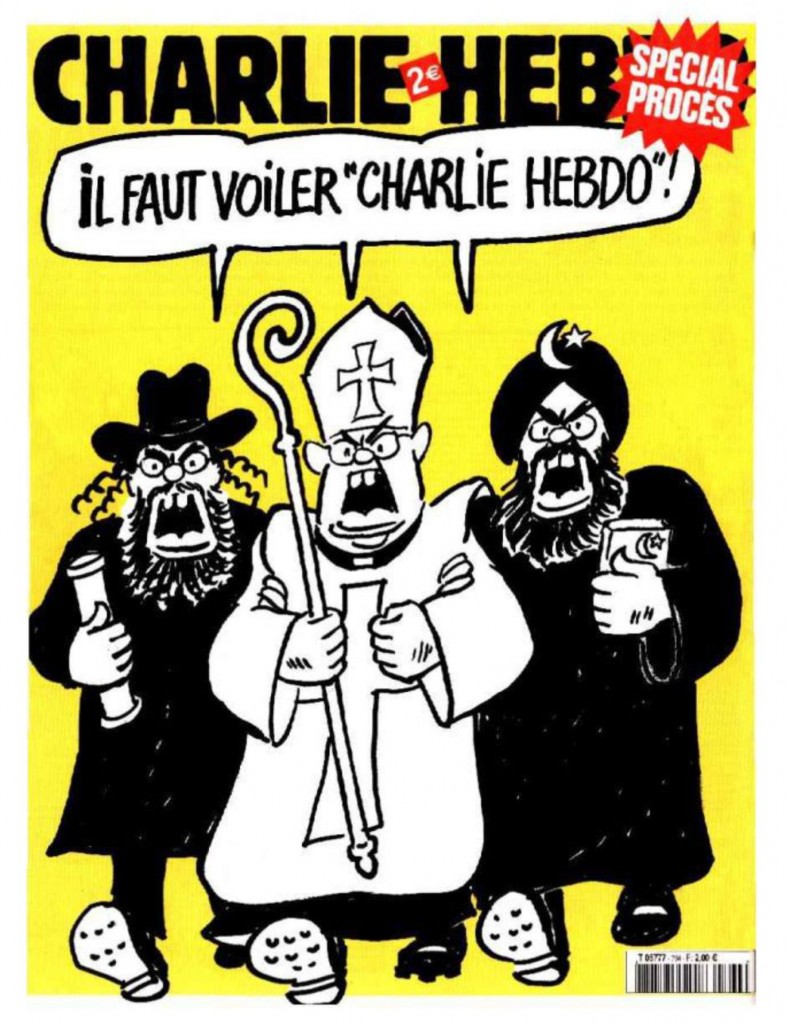

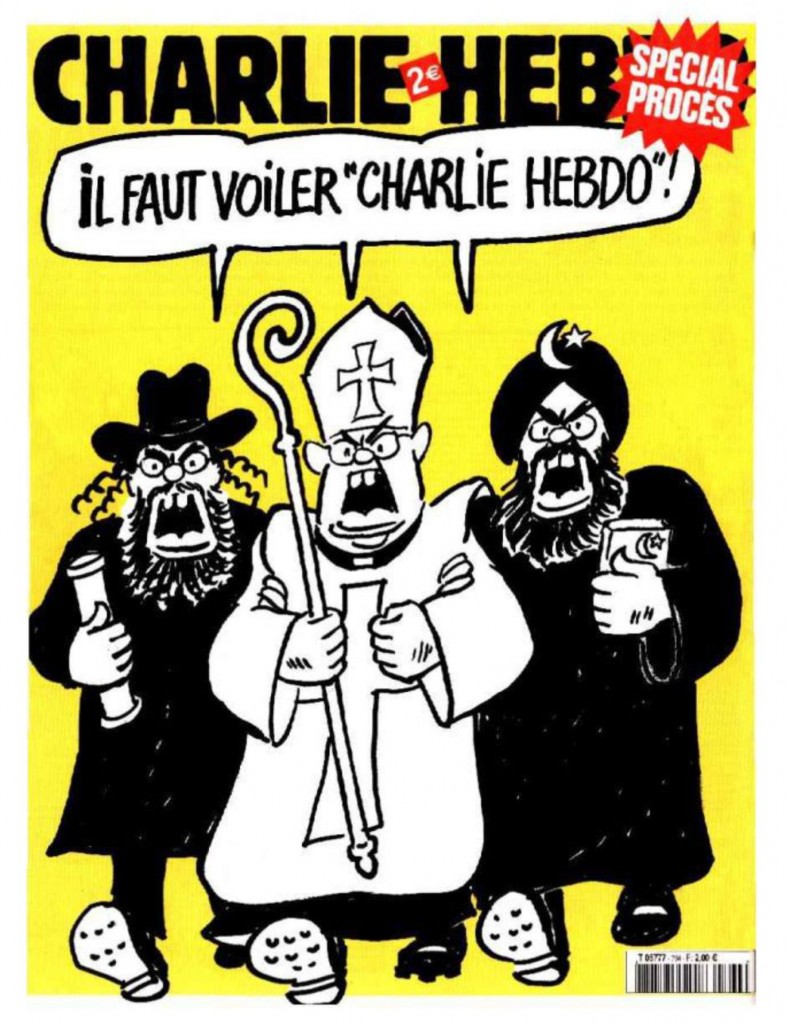

The journalists and cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo have a right to be offensive. Although they have most notably mocked Islamic beliefs, they have also mocked Judaism and Christianity and invoked the ire of many different religious leaders. The cover on the right is from 2007 during the magazine’s trial (procès) for hate speech. It portrays the leaders of Judaism, Christianity and Islam all calling out for Charlie Hebdo to be censored. The use of the word voiler for censorship provides an added irony in that its non-metaphoric meaning is to “veil” or “hide from sight.” If we grant religions amnesty from ridicule, we shall soon be asked to limit our mockery of politicians, and then we would be on the slippery slope to tyranny.

The journalists and cartoonists of Charlie Hebdo have a right to be offensive. Although they have most notably mocked Islamic beliefs, they have also mocked Judaism and Christianity and invoked the ire of many different religious leaders. The cover on the right is from 2007 during the magazine’s trial (procès) for hate speech. It portrays the leaders of Judaism, Christianity and Islam all calling out for Charlie Hebdo to be censored. The use of the word voiler for censorship provides an added irony in that its non-metaphoric meaning is to “veil” or “hide from sight.” If we grant religions amnesty from ridicule, we shall soon be asked to limit our mockery of politicians, and then we would be on the slippery slope to tyranny.

We should nevertheless perhaps not flaunt the ridicule. Just as we do not put up pornographic illustrations in public places, perhaps the Charlie Hebdo cartoons should not be displayed beyond the front cover of the magazine.

In addition, we should as best as possible grant those with religious beliefs, regardless of their creed, rights equal to other citizens: rights to work, security, education, equality before the law. A civil society grants each of its members their dignity. Ridicule is better used to hold the powerful in check than to demean the powerless.

And, just as in pornography, children require special protection. They should be taught tolerance; they must not be indoctrinated to hate. Schools are not a place for either denial of the Holocaust or defamation of the Prophet. The Charlie Hebdo cartoons might be carefully discussed, though this would take a highly sensitive teacher. No child should feel herself or himself subject to ridicule because of their origins or beliefs. That would be bullying.

References

Altman, A. (2012). Freedom of expression and human rights law. The case of holocaust denial. In Maitra, I., & In McGowan, M. K. Speech and harm: Controversies over free speech. (pp. 24-49). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Callamard, A. (2005). Striking the right balance.

Coetzee, J. M. (1996). Giving offense: Essays on censorship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Cruikshank, J. (2015). Why we won’t run the Charlie Hebdo cartoons. Toronto Star, January 16, 2015.

Dacey, A. (2012). The future of blasphemy: Speaking of the sacred in an age of human rights. London: Continuum.

Douthat, R. (2015). The blasphemy we need. New York Times. January 7,

Feinberg, J. (1985). The moral limits of the criminal law. Volume 2: Offense to others. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

MacKinnon, C. A. (1987).Feminism unmodified: Discourses on life and law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mayer, A. E. (2006). Clashing human rights priorities: How the United States and Muslim countries selectively use provisions of international human rights law. Satya Nilayam: Chennai Journal of Intercultural Philosophy, 44, 44-77.

Mertl, S., & Ward, J. (1985). Keegstra: the trial, the issues, the consequences, Saskatoon, Canada: Western Producer Prairie Books.

Mill, J. S. (1859/1864). On Liberty. 3rd Edition. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green. (Available at archive.org)

Milton, J. (1644) Areopagitica.

Shoemaker, D. W. (2000). “Dirty words” and the Offense Principle. Law and Philosophy, 19, 545-584.

Tariq Ali (2015). ‘It didn’t need to be done.’ London Review of Books. February 5, 2015.

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

United Nations (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

United Nations (1990/1993). Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. U.N. Doc.A/CONF.157/PC/62/Add.18

United Nations (1993). Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action Adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna on 25 June 1993

United Nations (2008). Resolution 7/19. Combating defamation of religions.

van Mill, D. (2012). Freedom of speech. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Walkom. T. (2015) Blasphemy is punishable in Canada. Toronto Star, January 17, 2015.

West. C. (2012). Pornography and censorship. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.