Antisemitism

Hatred is directed anger. Though we can claim metaphorically to hate

unconscious objects or abstractions, hatred is typically directed at another person or persons. Hatred is evoked by suffering that we perceive they caused. Since it leads to actions against these persons, hatred can also be described as “ill

will.”

Emotions can overwhelm reason. Passion is not logical. We often hate

without any justification. Hatred must then be maintained by fictions that describe the evil nature of those we hate.

Antisemitism is the most enduring and most unjustified of human hatreds.

The ill will suffered by the Jewish people has lasted for thousands of years, and has led to countless crimes, the most terrible of which was the Holocaust wherein 6 million Jews were put to death by the Nazi Government of Germany (Bauer, 2001; Marrus, 1987). ;

Antisemitism has been inspired by many fictions. This posting considers the unfortunate power of some of the stories that paved the way to the Holocaust.

Some Simple Psychology

Anger arises when we experience suffering, especially when we believe it

to be unwarranted, and when we are thwarted from achieving what we desire,

especially when we believe that we entitled to it. Anger seeks to attack these causes: to hit out at those who strike us; to break those who obstruct us.

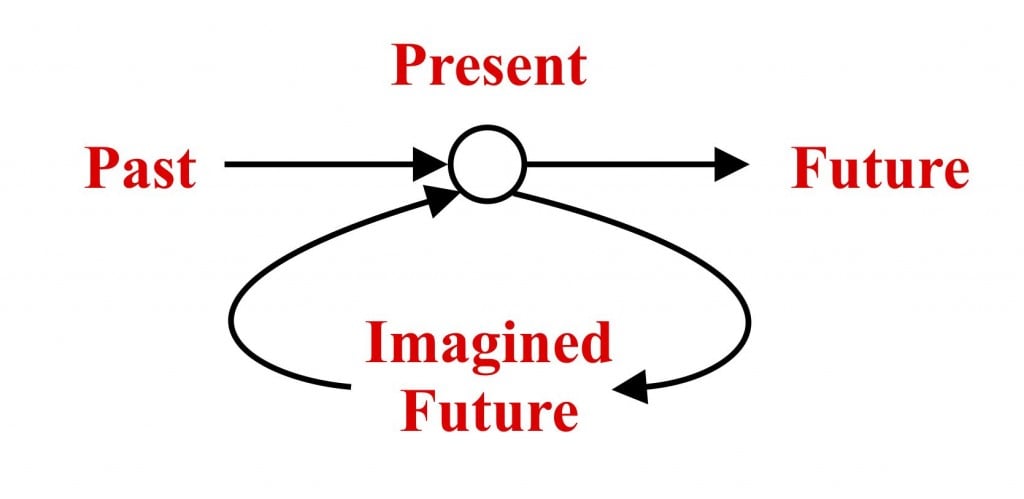

We tend to think of events as caused by persons. Even when forces of

nature act against us we may attribute them to a divinity or a devil, or to

those who worship them. Only in that way can anger find a target for its

release.

Sometimes the causes of our anger are too complicated to understand or too powerful to fight against. In these cases, we may vent our anger elsewhere and attack other human beings, while inventing plausible (though fictional) reasons for so doing.

…every instance of suffering, every feeling of displeasure, by whomsoever and in whatsoever way it may have been caused, whether it arises from the guilt or from the lawful activity of another person, or through the sufferer’s own fault, or without any fault, or even without any human influence, tends to transform itself into a feeling of enmity, to direct itself against fellow-humans and if possible to express itself against them. (Bernstein, 1951, p 85)

As we were growing up during childhood, we realized – at about the age

of three – that we can exert some control over our environment. We therefore created a self as the agent of this control. At about the same time we realized that the world contains other agents. These could either help us or hinder us. We became comfortable with those that helped and learned to cooperate with them. We feared the others.

The group appears to be a curious form of extension of the individual. It seems as if under the influence of the necessities of human communal life, human beings who need love and produce hate combine into new, collective and collectively selfish individualities of a higher order; directing their love inwards, their hate outward, their social instincts towards the insider, their anti-social tendencies toward the outsider. (Bernstein, 1951, p 109-110)

Those who cooperated in groups came to have similar desires and modes of

behavior. They followed the same rules and sought the same goals. Those who

were different became isolated. These “others” challenge our group-identification (Chanes, 2004, p 3). In our search for where to vent our anger, we often light upon those that are different from us. Especially if these people are small in number and not inclined to violence.

While for normal group enmity a certain regularity in the mutual expression of enmity is characteristic, the antagonism between a powerful majority and a powerless minority is characterised by a onesidedness of hostile actions which is fatal for the minority. For the latter is exposed to continual attacks and must confine itself to laborious attempts to maintain its existence, without a chance to resist actively to any extent; even its passive means of defense are totally inadequate and its existence often has to rely on nothing but periodical flight from place to place. This onesided relation of

permanent attack and failing defense is called persecution. Weak minority

groups are usually persecuted more or less emphatically. (Bernstein, 1951, p 224)

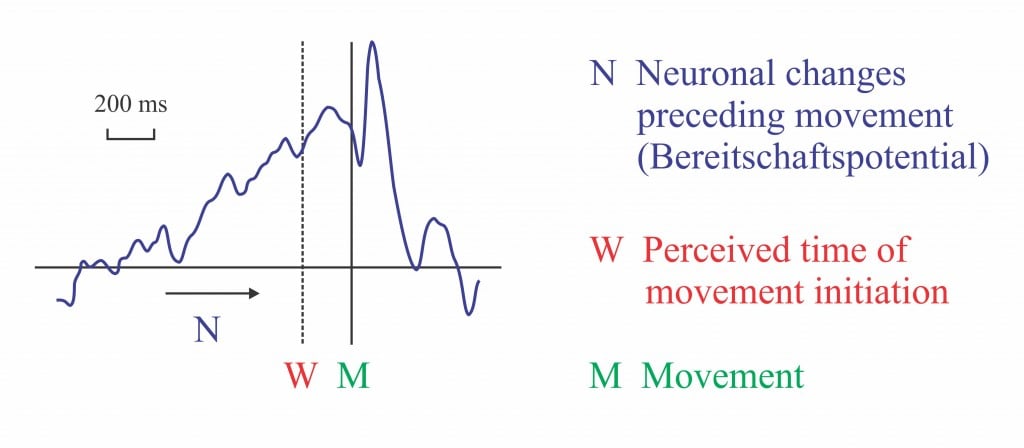

The actual psychological mechanisms that lead to antisemitism are not

really understood. Some believe that there are personality-types that are more easily convinced to vent their hatred on minorities. The role of authority and power is undoubtedly a factor (Morse & Allport, 1952; Milgram, 1974). Those who seek power or wish to maintain it gain great support by fomenting hatred. Propaganda – invented stories – have a tremendous power. For some reason the more incredible the story the more easily it is believed (Baum, 2012). Dehumanization of the victims serves to attenuate our inherent tendency to help our fellows. (Bandura et al., 1975)

For millennia the Jewish people have allowed us to vent our hatred. For

millennia we have invented reasons for our violence.

The hostility toward a minority exacerbates the feelings that initially triggered. When persecuted, a minority does not fare well in society and often comes to appear even more deserving of denigration and oppression (Beller, 2007, p 5).

Antisemitism is not caused by the Jews but by the inadequacy of those who need to hate them.

…two psychological characteristics are present in the individual antisemite: excessive hostility and the need (and a capacity) to project one’s aggression on other groups. Persons who have these traits generally suffer from feelings of inadequacy and from the feeling that their own personal borders, psychologically speaking, are easily invaded by others (Chanes, 2004, p 7)

We can perhaps conclude this section with two epigrams from Jean-Paul Sartre (1948):

If the Jew did not exist, the anti-Semite would invent him (p 13)

Antisemitism is not a Jewish problem: it is our problem. (p 152)

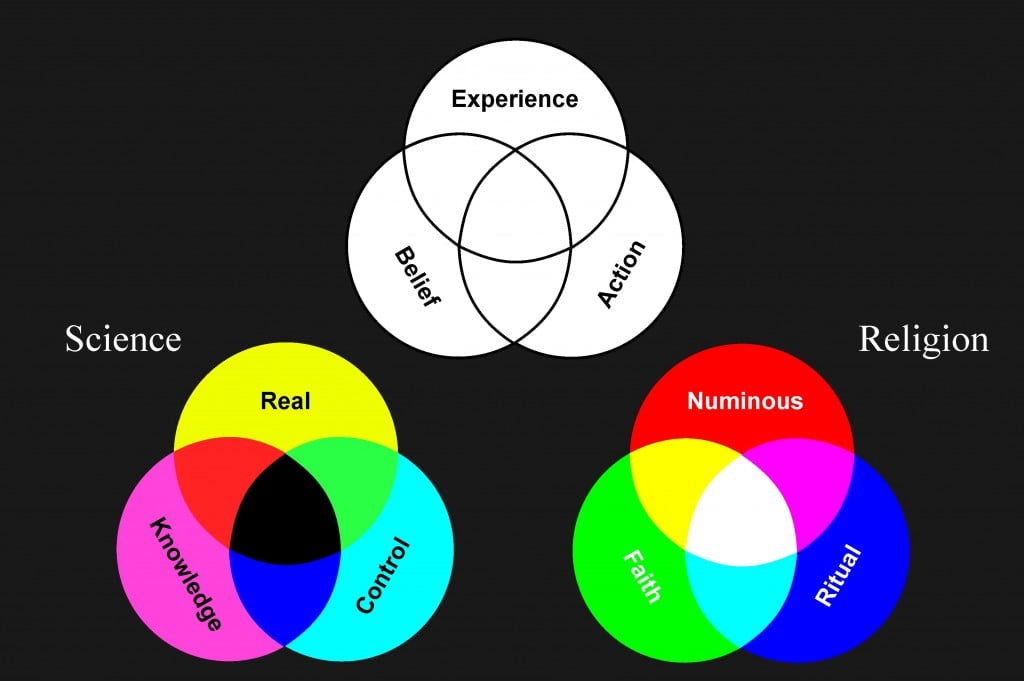

The People of the Covenant

The Jews consider themselves God’s chosen people. In the Hebrew

scripture Yahweh made a covenant with Abraham, and then renewed the covenant with Jacob and with Moses. The Jews were to worship Yahweh as the one true God and to follow his commandments. The Jews would then serve as an example for the rest of humanity

I the Lord have called thee in righteousness, and will hold thine hand, and will keep thee, and give thee for a covenant of the people, for a light of the Gentiles (Isaiah

42:6).

In return, the Jews would be considered special

For thou art an holy people unto the Lord

thy God, and the Lord hath chosen thee to be a peculiar people unto

himself, above all the nations that are upon the earth. (Deuteronomy 14:2)

And were promised as their home the land containing what is now the country of Israel

In the same day the Lord made a covenant with Abram, saying, Unto thy seed have I given this land, from the river of Egypt unto the great river, the river Euphrates (Genesis 15:18)

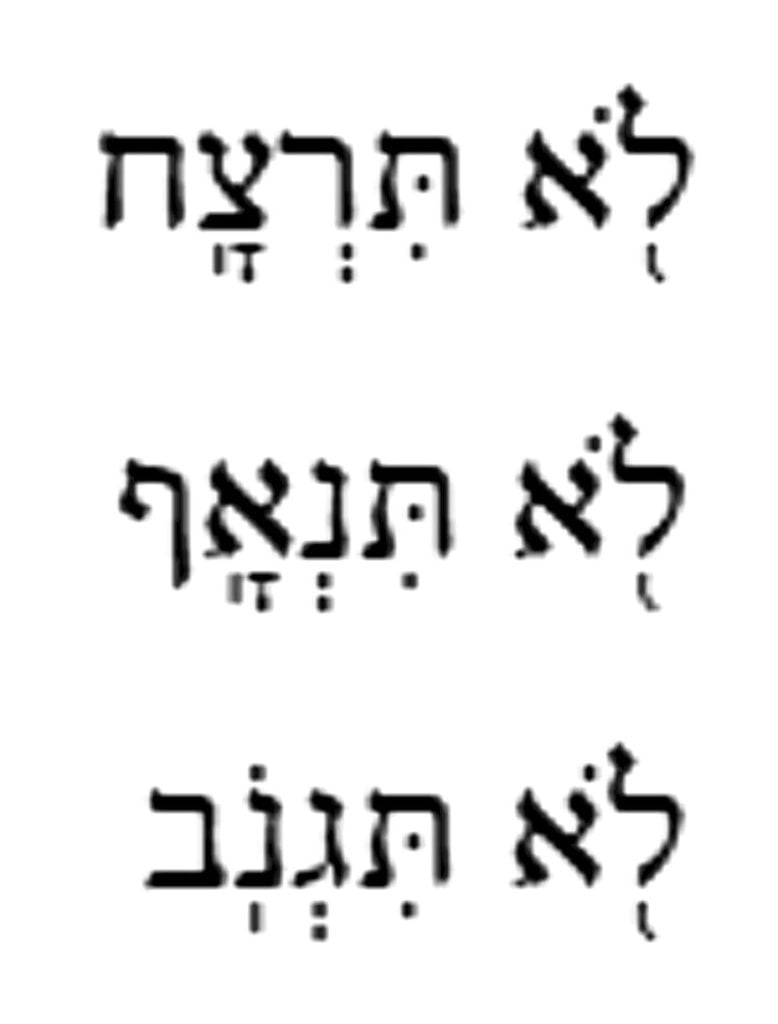

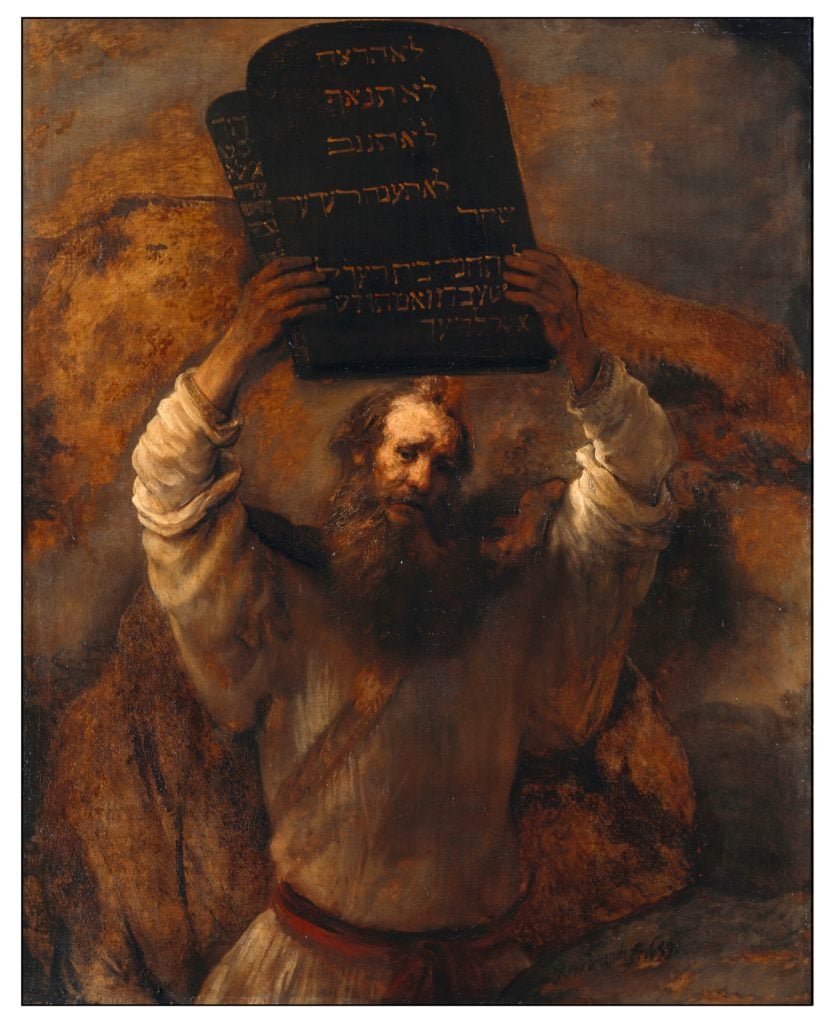

God’s covenant with the Jews was based on their keeping the commandments that he revealed to Moses. Rembrandt’s 1659 painting Moses with the Tablets of the Law shows Moses holding aloft the stone tablets on which the Ten Commandments had been written. These were engraved on two separate stones (Exodus 31:18, 32:15). In the painting, only the second tablet is completely visible giving the 6th to 10th commandments (Exodus 20:13-17). These begin with: “Thou shalt not kill. Thou shalt not commit adultery. Thou shalt not steal:” (Hebrew illustrated on the right).

No one is sure what moment in the story of the tablets Rembrandt is representing. Is it when he first displays these to the Hebrews? or when he is about to shatter them on the ground because the Hebrews had been worshipping the Golden Calf while he had been on Mount Sinai with God (Exodus 32:19)? or is it when he returns to God and brings a second set of tablets back to the chastised Hebrews (Exodus 34:1). Moses’ face is shining with revelation rather than angry. Perhaps, Rembrandt has painted the moment when Moses first displays the commandments.

No group of people is perfect. However, the Jews have contributed more than their share to the human endeavor – in philosophy, science, medicine, politics, art, music, literature. And for the most part the, laws that they accepted as part of their covenant with God have served them well. They are indeed an example to other people.

So why were and are they so often reviled? It is unlikely a reaction to their chutzpah in claiming to be God’s chosen. In the Middle Ages this was called the Insolentia Judaeorum. Yet every one of the world’s many religions claims to be just as special.

One defining aspect of the Jewish religion is that it is monotheistic. The first commandments state that a Jew must obey Jehovah and not even pay lip-service to any other god or idol:

I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage.

Thou shalt have no other gods before me.

Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth.

Thou shalt not bow down thyself to them, nor serve them

(Exodus 20:2-5).

The Jewish religion thus combines the worship of one god with strict obedience to his commandments. As Prager and Telushkin (2003) have suggested, this ethical monotheism may have offended those who followed other gods. Jews refused to follow the proverbial injunction that when in Rome do as the Romans do. For example, the outburst of violence against the Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE (then part of the Roman Empire) was triggered by their refusal to place statues of the Emperor Caligula in their temples (Goldstein, 2012).

One should respect the beliefs of others. However, respect does not mean obeying rules that go against one’s own moral principles. The Jewish people’s refusal to acknowledge or worship other gods has continued to the present. In particular Jews do not recognize the divinity of Jesus Christ.

In addition to the Ten Commandments, Yahweh’s covenant with the Jewish people involved numerous other rules of behavior. These included strict stipulations about the types of food that they might eat and the methods in which this food should be prepared. Over the ages observant Jews have thus been unable to share meals with those of other faiths. And although some of the ancient Jewish philosophers – Hillel and Maimonides for example – were open to ideas beyond the Covenant, strict Judaism limited itself to the study of the Torah and its interpretations.

The Covenant with Yahweh thus isolated the Jewish people from the rest of humanity. They could not share the beliefs, the food or the thoughts of others. They antagonized others by their claim to be the chosen people.

So we have the idea that antisemitism is in part caused by the very character of the Jewish religion. This would explain why the Jews have been reviled by so many different people in so many different countries. The following was written Bernard Lazare in 1894. He was a Jewish polemicist who wrote the first defense of Captain Alfred Dreyfus. Yet even he thought that the Jews were partly to blame for antisemitism.

Inasmuch as the enemies of the Jews belonged to divers races; as they dwelled far apart from one another, were ruled by different laws and governed by opposite principles; as they had not the same customs and differed in spirit from one another, so that they could not possibly judge alike of any subject, it must needs be that the general causes of antisemitism have always resided in Israel itself, and not in those who antagonized it…. Which virtues or which vices have earned for the Jew this universal enmity? Why was he ill-treated and hated alike and in turn by the Alexandrians and the Romans, by the Persians and the Arabs, by the Turks and the Christian nations? Because, everywhere up to our own days the Jew was an unsociable being. (Lazare, 1894/1903, pp 8-9)

This seems so reasonable. Yet it is false. It does not explain the cause of antisemitism. It is just an excuse. It blames the victim for the crime.

The Crucifixion of Christ

In the early decades of the Common Era, Jesus, a Jewish teacher from Nazareth, brought new insight to the interpretation of Jewish law. He simplified the commandments by expressing them as the need to love the Lord and to love one’s neighbor as oneself. He criticized the rigid adherence to the Sabbath, and the commercialization of the Temple. He proclaimed the idea of a Kingdom of Heaven. Many of the more observant Jews were disconcerted by his teachings. The Romans were upset that he was proposing a new kingdom. Jesus was arraigned before Pilate, the Roman governor of Judea, condemned and crucified.

A few days after his death and burial, the tomb of Jesus was found empty. Many of his followers claimed that they afterwards saw him in person. They therefore believed that he had been resurrected. They continued to meet and discuss his teachings. They were either tolerated by other Jews or condemned as heretics.

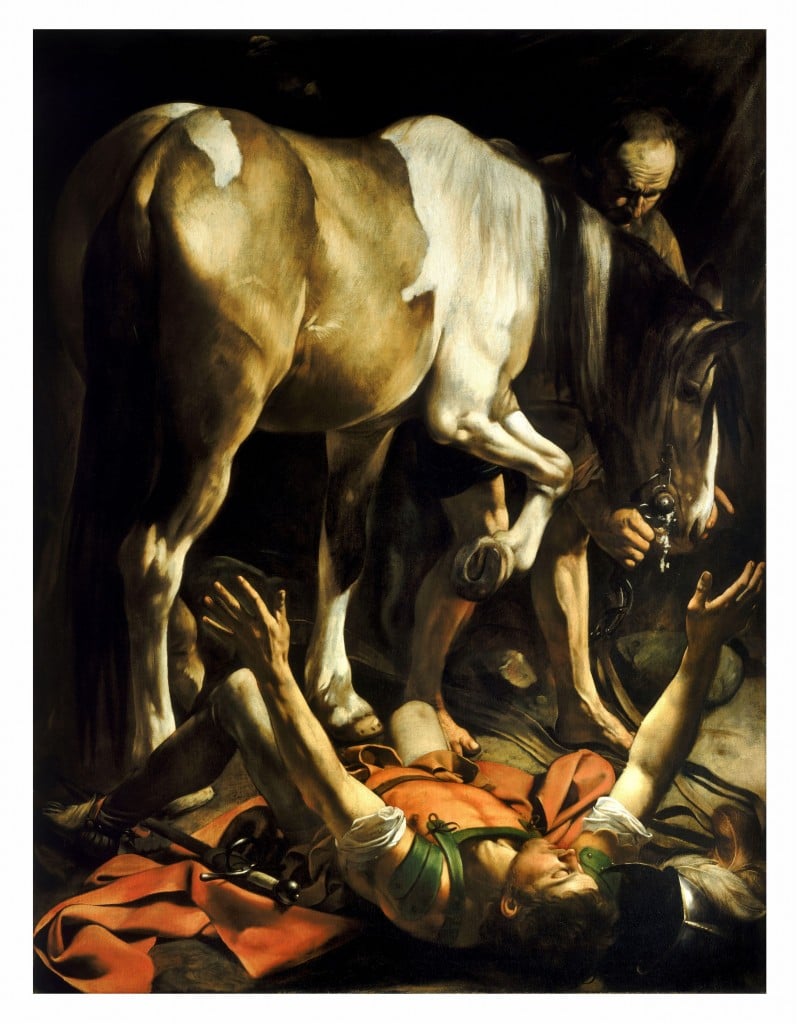

A learned Jew named Saul was one of those that persecuted the followers of Jesus. However, on the road to Damascus he had a vision of Jesus that completely altered his thinking. He changed his name to Paul, and began to provide an over-arching theory about the death and resurrection of Jesus. His main ideas were that Jesus was the Son of God, the Messiah prophesied in the scriptures, that he died to release us from our sins, and that we shall all be saved from death by having faith in Jesus called Christ (the “anointed”).

For I delivered unto you first of all that which I also received, how that Christ died for our sins according to the scriptures;

And that he was buried, and that he rose again the third day according to the scriptures (I Corinthians 15:3-4)

Paul’s major teaching was that one could never attain salvation by following the Mosaic laws. No one is perfect. Everyone breaks the law. However, Christ offers salvation if we repent our sins and have faith in him.

Knowing that a man is not justified by the works of the law, but by the faith of Jesus Christ, even we have believed in Jesus Christ, that we might be justified by the faith of Christ, and not by the works of the law: for by the works of the law shall no flesh be justified. (Galatians 2:16).

Paul’s letters describing these ideas are the earliest of the Christian scriptures. Written in the years 50-60 CE these predate by 20 to 50 years the four gospels, which describe the life and teachings of Jesus.

The followers of Jesus in the 1st Century CE differed in their opinion about his relationship to the Jews. Some thought that the message of Jesus was for the Jews; others that it was for both Jews and Gentiles. Most of Paul’s teaching was directed to the Gentiles. In some of his letters he laments the inability of many of his Jewish colleagues to understand God’s new covenant.

For ye, brethren, became followers of the churches of God which in Judaea are in Christ Jesus: for ye also have suffered like things of your own countrymen, even as they have of the Jews:

Who both killed the Lord Jesus, and their own prophets, and have persecuted us; and they please not God, and are contrary to all men:

Forbidding us to speak to the Gentiles that they might be saved, to fill up their sins alway: for the wrath is come upon them to the uttermost.

(I Thessalonians 2:14-16)

Some of the gospels continued this criticism of the Jews (Crossan, 1995). This is perhaps most evident in the gospel of Matthew. He describes how the Jews forced Pilate to crucify Jesus, and willingly accepted the responsibility for his death:

When Pilate saw that he could prevail nothing, but that rather a tumult was made, he took water, and washed his hands before the multitude, saying, I am innocent of the blood of this just person: see ye to it.

Then answered all the people, and said, His blood be on us, and on our

children. (Matthew 27: 24-25)

The major event in Jewish history of the 1st Century CE was the Great Revolt of the Jews against Roman rule. This began in 66 CE and culminated in the Destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. The illustration below shows a representation in the Arch of Titus of the Romans carrying the spoils from the temple. Among the spoils is the great Menorah that once gave light to the Tabernacle.

At this time many Jews fled their homeland and settled in other countries. The Jewish people have been exiled at many times in its history – the Assyrian conquest (733 BCE), the Babylonian captivity (597 BCE), the Great Revolt (70 CE), the later Bar Kokhba Rebellion (132 CE). Though some Jews remained in Israel, most lived in the Diaspora (“scattering”) – far from the land that from the days of Moses they had considered their God-given home.

The Destruction of the Temple seemed to many Christians a divine response to the action of the Jews in crucifying their Lord. Though the Romans crucified Jesus, some of the early Christians considered the Jews responsible. The Jews were thus guilty of deicide and should be reviled and cast out from Christian society. Even if they were not guilty, they should be chastised for not recognizing the salvation offered by Christ – for staying with the old dispensation rather than following the new.

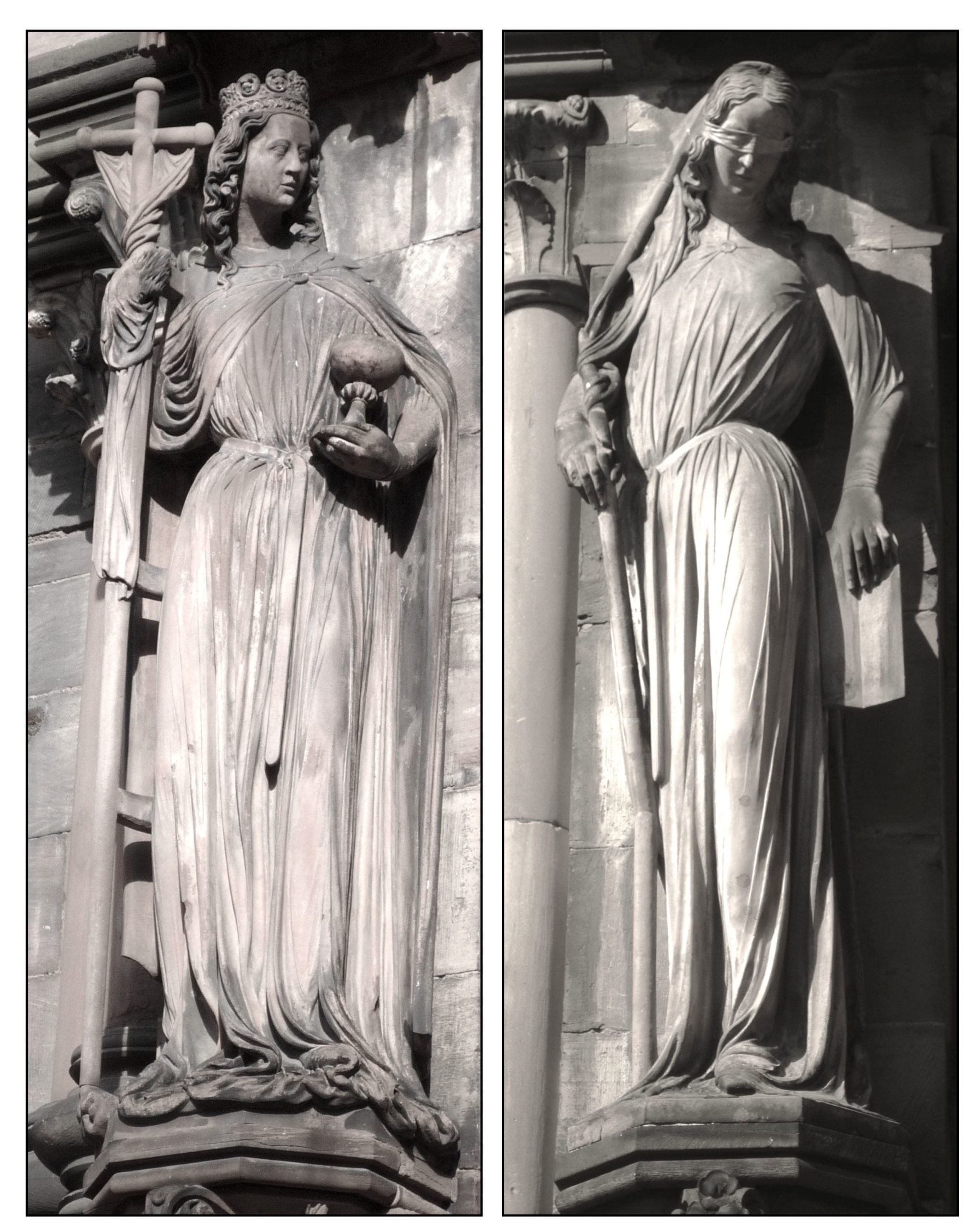

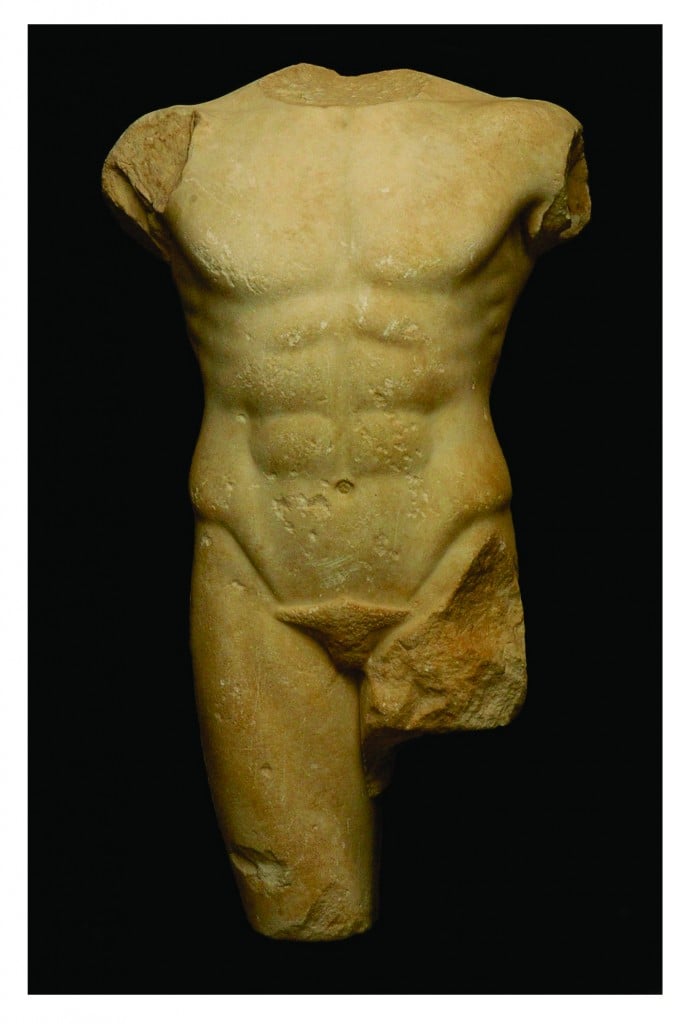

These ideas have long permeated the thinking of the Christian Church. Many of the cathedrals illustrate these concepts by contrasting sculptures of Ecclesia and Synagoga. The statues on the south portail of the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Strasbourg from the 13th Century CE are particularly impressive. Legend has it that these were created by a female sculptor Sabina von Steinbach, though there is no real evidence for this. Ecclesia with her crown, holds in her hands the cross and the chalice. She looks with pity on Synagoga, who is blindfolded and cannot see the truth. She holds in her hands the tablets of the law and the lance that the centurion used to bring the crucifixion to an end. The lance was shattered by the resurrection.

The following illustration shows the complete portail. Ecclesia and Synagoga are on the left and right sides. In the center sits Solomon in judgement between the old covenant and the new. Above him is Christ, Salvator Mundi (savior of the world). The carvings in the tympanums represent the dormition, assumption and coronation of the Virgin Mary.

The statues of Ecclesia and Synagoga are impressive examples of gothic art. Though superficially beautiful, they obscure rather than convey the truth. The feelings against the Jews that they evoke are a complete betrayal of Jesus, a Jew who taught in the synagogues of Palestine.

One might have hoped that the antisemitism of the Christian Church would have been excised by the Reformation. But this was not to be. Martin Luther was virulently antisemitic. In his The Jews and Their Lies (1543, pp 39-42) he advises Christians to burn their synagogues of the Jews, their houses, and their books, prohibit their Rabbis from teaching, not allow them to travel on the highways, and prohibit them from lending money. Luther was a harbinger of Kristallnacht.

Wild Accusations

During the Middle Ages people could not understand why life was so often brutal. An easy way to explain the various disasters was to attribute them to the Jews. If the Jews could kill God, there was no telling what other crimes they were capable of.

On Good Friday in 1144 the body of a child called William was discovered in the woods near Norwich in England. The Jews were accused of murdering the child. No credible evidence was ever found. However, a monk who had just converted from Judaism to Christianity claimed that the Jews had decided to sacrifice a Christian child to re-enact the death of Christ. Several Jews were slaughtered. William was declared a martyr. Pilgrims flocked to his tomb. Miracles occurred.

William of Norwich was the first documented case of Jews being accused of ritual murder. As the years went by similar accusations arose in multiple different regions of Europe (Goldstein, 2012). Many of these cases included the idea that the Jews used the blood of their victims to make the unleavened bread used in the celebration of Passover. This particular accusation was called the “blood libel.” It makes no sense. Kosher regulations require that observant Jews never eat food contaminated with blood. Jews go to great lengths to remove blood from meat before it can be eaten.

The Christian Bible contains the Hebrew scriptures in what it calls the Old Testament. Some of these writings described how the blood of sacrificed animals played an important role in the ceremonies of the ancient Hebrews, e.g.

And he shall kill the bullock before the Lord: and the priests, Aaron’s sons, shall bring the blood, and sprinkle the blood round about upon the altar that is by the door of the tabernacle of the congregation. (Leviticus 1:5).

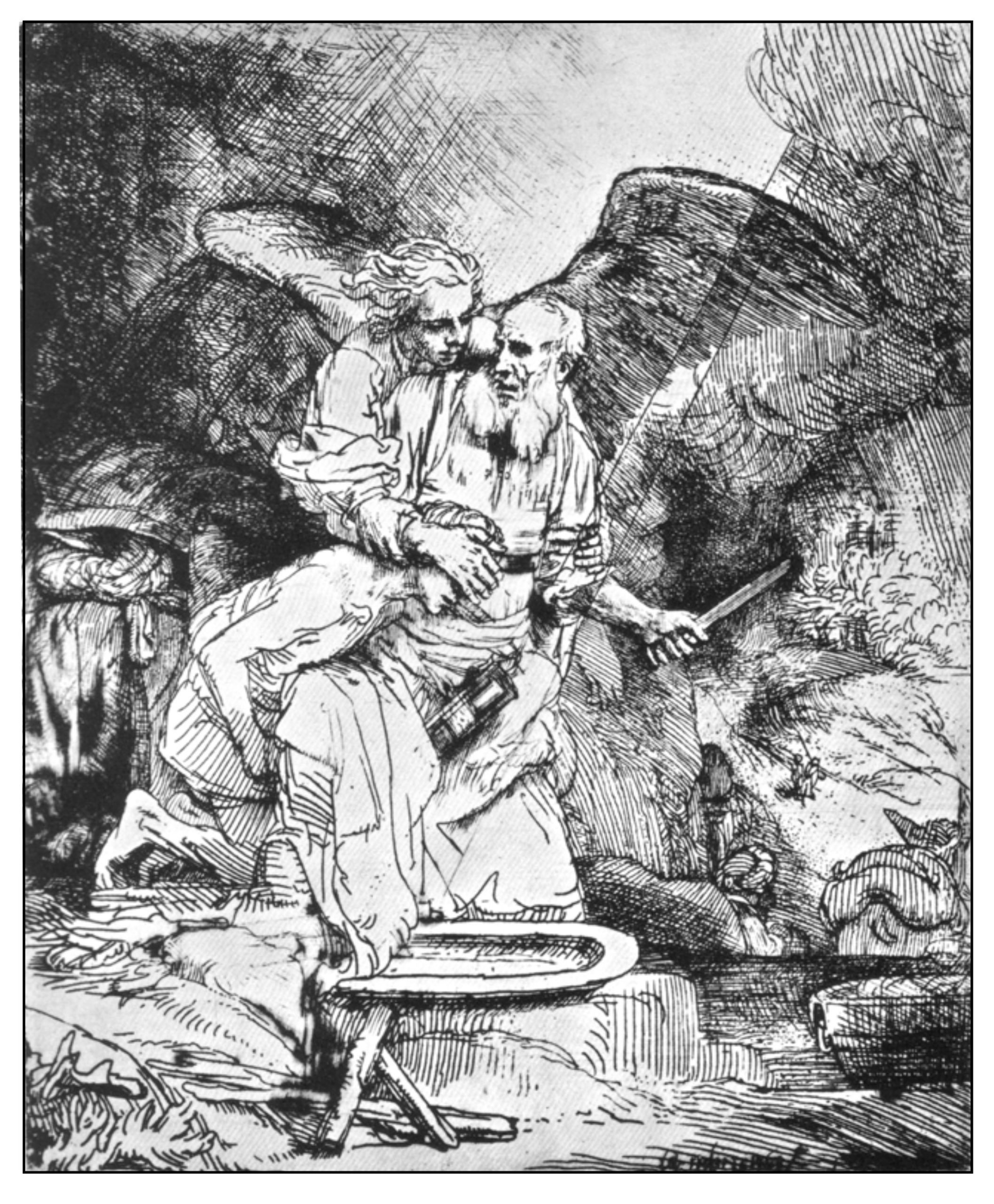

Other ancient Hebrew writings are even more disconcerting. One of the foundational stories of Judaism is the Akedah (“binding”), wherein the Patriarch Abraham, at the request of Jehovah, takes his son Isaac to Mount Moriah to sacrifice him (Genesis 22). Although an angel stays Abraham’s hand at the last moment, this fails to attenuate the story’s horror. The illustration below shows Rembrandt’s 1655 etching.

The Old Testament contains other stories wherein children were sacrificed. To defeat the Ammonites, Jephthah promised the Lord that he would sacrifice whatever came out of his house when he returned from battle. Jehovah gave the victory to the Israelites. When Jephthah returned home, his daughter came to greet him, dancing and playing the tambourine (Judges 11).

There is also a suggestion that King Manasseh sacrificed his son – the wording is “he made his son pass through the fire” (2 Kings 21:6). These events and the idea that the terrible place near Jerusalem called Gehenna or Tophet was actually a site of human sacrifice are discussed at length by Stavrakopoulou (2004). The practice was banned by Yahweh speaking through his prophet Jeremiah:

And they have built the high places of Tophet, which is in the valley of the son of Hinnom, to burn their sons and their daughters in the fire; which I commanded them not; neither came it into my heart. (Jeremiah 7:31).

One can perhaps imagine how such stories from the Old Testament might have allowed credulous people to accept the idea that the Jews might sacrifice Christian children and use their blood for their ceremonies. When one’s faith requires a belief in miracles, wild rumors are not easily contradicted.

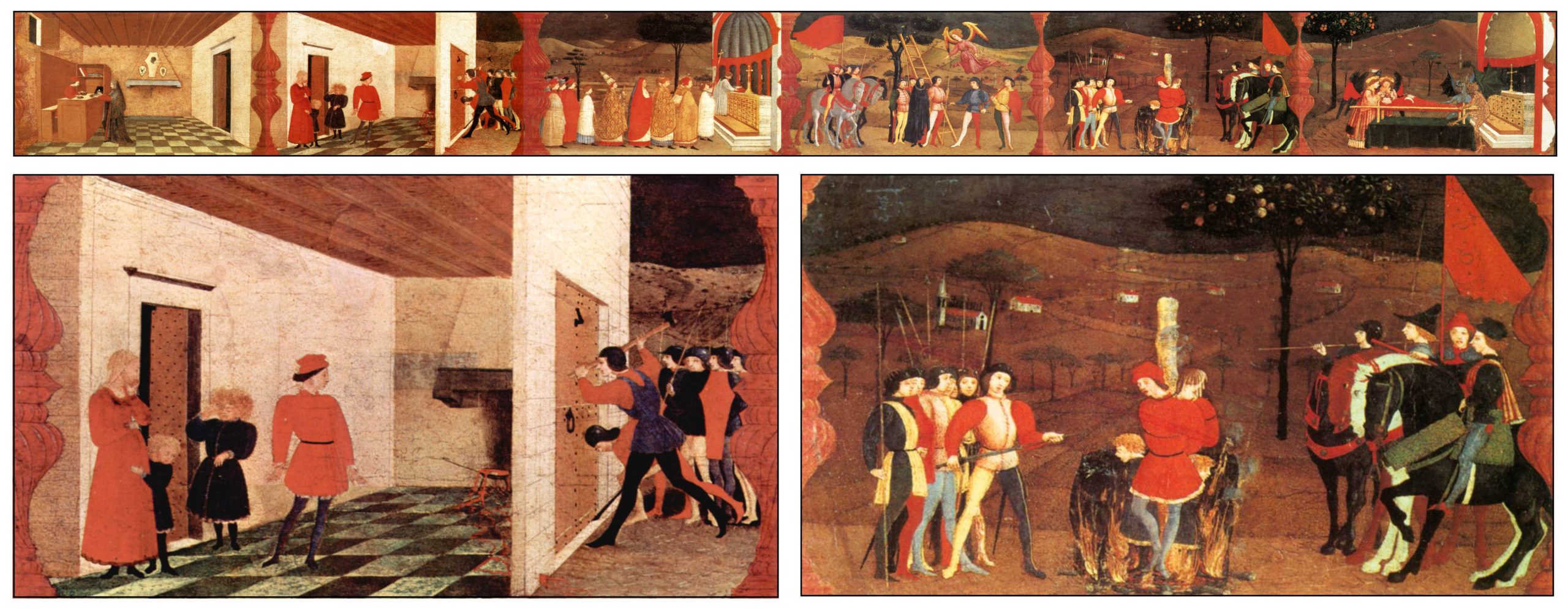

The main sacrament of the Christian Church is the Eucharist, wherein the congregation partakes of bread and wine that have been especially blessed. According to the church, these had been miraculously “transubstantiated” to the body of Jesus, who was sacrificed to save the world. The sacramental bread is called the host (from the Latin hostia for sacrificial victim). In many places and at many times the Jews were accused of “desecrating” the host. The following illustration shows a 1469 sequence of paintings by Paolo Uccello that tell the story of the Miracle of the Desecrated Host. Both the full sequence and the particular panels illustrating the second and fifth episodes are shown. The paintings were on the predella to the altar in the Corpus Domin church in Urbino. The retable painting above the predella by Justus van Gent presented the Institution of the Eucharist.

The six episodes in the predella show

- a woman sells a portion of the consecrated host to a Jewish merchant

- when the Jew tries to burn the host, it starts to bleed, alerting the city guards

- a holy procession is needed to re-consecrate the host

- the woman is burned at the stake; she repents and an angel descends from heaven to save her

- the Jew and his family are burned at the stake; no angel intervenes

- two angels and two devils argue over the woman’s body

As the Black Death (Bubonic Plague) spread across Europe in the 14th Century, Jews were accused of poisoning wells and spreading the disease. Many Jews were condemned to death by fire fort these crimes. No one noticed that Jews died from the pandemic just as frequently as their Christian neighbors. Nor that burning Jews at the stake had no effect on the spread of the disease. A half century later, Jacob von Königshofen wrote a critical history of these times. The following is his description of the massacre of the Jews in Strasbourg at the height of the Black Death in 1349:

In the matter of this plague the Jews throughout the world were reviled and accused in all lands of having caused it through the poison which they are said to have put into the water and the wells – that is what they were accused of – and for this reason the Jews were burnt all the way from the Mediterranean into Germany, but not in Avignon, for the pope protected them there. On Saturday-that was St. Valentine’s Day, they burnt the Jews on a wooden platform in their cemetery. There were about two thousand people of them. Those who wanted to baptize themselves were spared. Many small children were taken out of the fire and baptized against the will of their fathers and mothers. And everything that was owed to the Jews was cancelled, and the Jews had to surrender all pledges and notes that they had taken for debts. The council, however, took the direct cash that the Jews possessed and divided it among the working men proportionately. The money was indeed the thing that killed the Jews. If they had been poor and if the feudal lords had not been in debt to them, they would not have been burnt. After this wealth was divided among the artisans some gave their share to the Cathedral or to the Church on the advice of their confessors. Thus were the Jews burnt at Strasbourg. (quoted in Marcus, 1938, p.47)

Forces other than the plague were at play. Debt caused as much suffering as disease. As the historian notes, “The money was indeed the thing that killed the Jews.”

Usury

The Old Testament contains several injunctions against usury. Originally “usury” was simply any interest charged on loans. The meaning of the term has changed as the relations between religion and commerce have developed. At present, usury is generally limited to exorbitant interest.

In one of the earliest mentions of usury in the Hebrew Scriptures, the Jewish people are forbidden to charge interest on loans to fellow-Jews although they may so charge strangers:

Unto a stranger thou mayest lend upon usury; but unto thy brother thou shalt not lend upon usury (Deuteronomy 23:20).

In the New Testament usury is only occasionally considered:

But love ye your enemies, and do good, and lend, hoping for nothing

again (Luke 6:35).

Nevertheless, the Christian Church decided early in its history that usury was a sin (Moehlman, 1934). In the council of Nicaea of 327 CE it forbade clergy to collect interest on any debts. In the Third Lateran Council of 1179, it decreed

Since in almost every place the crime of usury has become so prevalent that many persons give up all other business and become usurers, as if it were permitted, regarding not its prohibition in both testaments, we ordain that manifest usurers shall not be admitted to communion, nor, if they die in their sin, receive Christian burial, and that no priest shall accept their alms. (Moehlman, 1934, pp 6-7)

Thus for most of the middle ages it was difficult for people in business to obtain financial support for their enterprises. Jewish merchants, untrammeled by Christian prohibitions, unable to own land, and often prevented from practicing trades because of exclusively Christian guilds, gradually assume the responsibility for lending money in return for interest (Foxman, 2010). Some kings and princes found the linguistic abilities and financial connections of the Jews appealing and appointed them to their courts. However, most Jews remained poor and unrecognized – traders, shopkeepers, pawnbrokers and minor moneylenders.

In later years the Catholic Church found itself in need of capital to build its churches, and revised its doctrine on usury, founding its own lending organizations called Mounts of Piety (Monte de Pieta). The oldest bank in the world, the Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, derives from one of these lenders. After the Reformation, Protestants re-interpreted the scriptures and established their own investment banks.

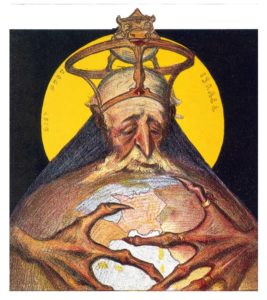

Jewish lenders prospered and some of our current banks have Jewish roots, the Rothschild banks and Goldman-Sachs being two of the biggest. However, almost all of the world’s largest banks were actually founded by Gentiles. The idea that the Jews control international banking is ludicrous. Why one should only consider the religion of a banker when he is Jewish is invidious (Foxman, 2010). One never mentions the Roman Catholic origins of the Bank of America or the Presbyterian origins of Wells Fargo. Yet Jewish bankers have long been game for hateful cartoons. The depiction of “King Rothschild” by Charles Lucien Léandre shown on the right is from the cover of Le Rire, April 16, 1898. Above Rothschild is the Golden Calf that was worshipped by the the idea of Mammon, the idol of wealth condemned in the New Testament:

No man can serve two masters: for either he will hate the one, and love the other; or else he will hold to the one, and despise the other. Ye cannot serve God and mammon. (Matthew 6:24).

The myth of Jewish greed has become a mainstay of antisemitic thought. Richard Wagner (1850) cannot get away from it even though he is supposed to be writing about music.

According to the present constitution of this world, the Jew in truth is already more than emancipate: he rules, and will rule, so long as Money remains the power before which all our doings and our dealings lose their force.

Even Jewish writers have been convinced of the myth

Thus, by himself and by those around him; by his own laws and by those imposed upon him; by his artificial nature and circumstances, the Jew was directed to gold. He was prepared to be changer, lender, usurer, one who strives after the metal, first for the pleasures it could afford and then afterwards for the sole happiness of possessing it; one who greedily seizes gold and avariciously immobilizes it. (Lazare, 1903, p 110).

The Pale of Settlement

As the Middle Ages progressed, the Jews were expelled from many European countries: England, 1290; France, 1306; Hungary, 1349; Austria, 1421; Spain, 1492; Portugal, 1497 (Baum 2012, p. 18). Other countries required that the Jews live apart from Christians in regions that came to be known as ghettos, from the Venetian dialect word for “foundry” located near where the first ghetto was established in Venice in 1516. Other ghettos were later set up throughout Italy, and then in Germany and in Poland (Goldstein, 2012, p 130)

Many of the expelled Jews moved to Eastern Europe. They settled in the

regions that now form the countries of Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine. Much of this area was then part of the Kingdom of Poland. Polish nobles welcomed the new immigrants. Many Jews were used as tax-collectors. This did sit well with some of the Eastern Orthodox Slavic people who chafed under the control of Catholic Poland. In 1648, the Cossacks in Ukraine rebelled under the leadership of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. During this war, tens of thousands of Poles and Jews were massacred (Bacon 2003). The Eastern Orthodox Church was every bit as antisemitic as the Roman Catholic Church. Ukraine became independent of Poland and soon became part of the Russian Empire. Later Poland itself would be partitioned between Prussia, Austria and Russia and cease to exist as an independent kingdom.

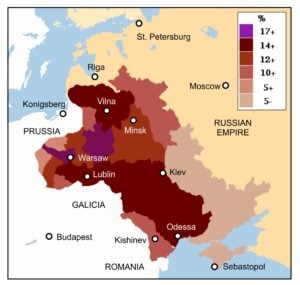

The “Pale of Settlement” was set up in 1791 by Catherine the Great. This was an area in the Western regions of the Russian Empire wherein Jews were allowed to live. The term “pale” refers to the stakes that delineated the area

The “Pale of Settlement” was set up in 1791 by Catherine the Great. This was an area in the Western regions of the Russian Empire wherein Jews were allowed to live. The term “pale” refers to the stakes that delineated the area

– the word was originally used to describe an area in Ireland under the control of the English crown. Over the years many of the Jews in central Russia were exiled to the Pale of Settlement. As shown in the map (adapted from Wikipedia, originally created by Thomas Gun) the Jewish percentage of the population in these regions was significant. Around 1900, the Jews in the Pale of Settlement numbered almost 5 million (about half the total number of Jews in the world), and formed about 10% of the general population of the area.

The ghettos and the Pale of Settlement separated the Jews from their neighbors. Their resultant isolation of the Jews increased their “unlikeness” or “otherness.” By closing them off in localized areas beyond the reach of normal civil authorities, it also made them more susceptible to random violence.

In 1881, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated in St. Petersburg by a group

of revolutionaries. The group Narodnaya Volya (“People’s Will”) was

composed of Russian-born anarchists, but one young woman was Jewish. The new Tsar Alexander III believed that the Jews were behind the assassination and unleashed a series of pogroms in the Pale of Settlement to avenge his father’s death.

The word “pogrom” derives from a Russian word for storm or devastation. Christians in a community were encouraged to murder their Jewish neighbors – killers of Christ and assassins of the Emperor. The police were ordered not to intervene. These pogroms continued into for several years. Thousands of Jews were killed.

The pogroms returned in 1903-1906 during the reign of Tsar Nicholas II. These appear to have been instigated by members of the Tsar’s secret police. One political rationale for these actions against the Jews was to rally the Russian people around the Tsar and against all those that were promoting the modernization of Russia.

The first pogrom of the 20th Century began in Kishinev, Moldava (then known as Bessarabia), on Easter Sunday in 1903. A child had been found murdered, and city leaders accused the Jews of his murder. Patriotism, blood libel and deicide worked together to create a rampaging and murderous mob (Penkower, 2004). The following is an illustration from the French Journal L’Assiette de Beurre of April, 1903, depicting the aftermath of the Easter pogrom.

The novel The Lazarus Project by Aleksander Hemon (2008), which tells the story of a survivor of the Kishinev pogrom who immigrated to the United States, provides a vivid description of the violence and its far-reaching consequents. The epic poem City of the Killings written in 1903 by the Jewish poet Chaim Bialik to commemorate the massacre begins:

Rise and go to the town of the killings and you’ll come to the yards

and with your eyes and your own hand feel the fence

and on the trees and on the stones and plaster of the walls

the congealed blood and hardened brains of the dead.

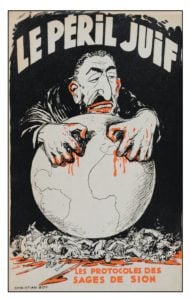

The Protocols

At about this time there appeared the first traces of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion (Nilus, 1906/1922). This document purported to be the secret plans of Jewish Leaders to take over the world. The protocols describe how these elders will sow dissension and confusion amidst the goyim and ultimately step in to rule:

In order to put public opinion into our hands we must bring it into a state of bewilderment by giving expression from all sides to so many contradictory opinions and for such length of time as will suffice to make the goyim lose their heads in the labyrinth and come to see that the best thing is to have no opinion of any kind in matters political, which it is not given to the public to understand because they are understood only by him who guides the public. This is the first secret.

The second secret requisite for the success of our government is comprised in the following; To multiply to such an extent national railings, habits, passions, conditions of civil life, that it will be impossible for anyone to know where he is in the resulting chaos, so that the people in consequence will fail to understand one another. This measure will also serve us in another way, namely, to sow discord in all parties, to dislocate all collective forces which are still unwilling to submit to us, and to discourage any kind of personal initiative which might in any degree hinder our affair. There is nothing more dangerous than personal initiative; if it has genius behind it, such initiative can do more than can be done by millions of people among whom we have sown discord. We most so direct the education of the goyim communities that whenever they come upon a matter requiring initiative they may drop their hands in despairing impotence. The strain which results from freedom of action saps the forces when it meets with the freedom of another. From this collision arise grave moral shocks, disenchantment, failures. By all these means we shall so wear down the goyim that they will be compelled to offer us international power of a nature that by its position will enable us without any violence gradually to absorb all the State forces of the world and to form a Super-Government. (Protocol 5)

The reader easily recognizes the confusions of the modern world. Our

natural paranoia quickly attributes this to outside agents rather than to the

simple complexity of political forces. Human beings have long imagined that our lives are controlled by secret societies such as the Templars, the

Rosicrucians, the Jesuits, the Illuminati, the Masons, and the New World Order (Eco, 1994, pp 132-139). The Protocols of the Elders of Zion identified these clandestine agents as the Jews.

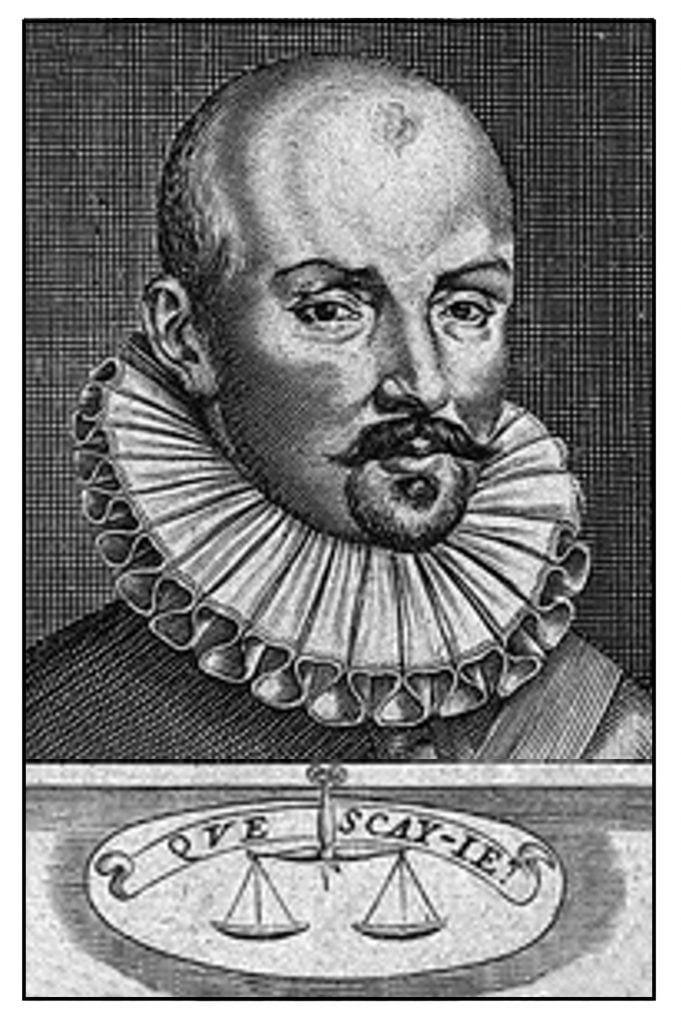

The protocols are a complete fiction (Eisner, 2005; Hagemeister, 2008). They were largely plagiarized from a satire against the French Emperor Napoleon II written by Maurice Joly in 1864 entitled The Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu (Graves, 1921). The most widely accepted story is that a Russian exile living in France, Mathieu Golovinski, adapted Joly’s satire into an antisemitic tract at the instigation of the Tsar’s secret police, who wished to impugn the forces of modernization in Russia, and to whip up hatred of the Jews as a distraction from the government’s problems.

Despite being proven a fiction, the Protocols have been republished over and over again. The illustration at the right shows the cover of a French Version published in 1934. The design is loosely based on Léandre’s 1898 cartoon depiction of Rothschild. The cover artist goes by the alias ‘Christian Goy.” In the 20th Century the Protocols are widely published in Muslim countries, where they serve to foster animus against Israel. Why do people still believe that this tract represents the truth? It is easier to believe in a simple fiction than in complex facts. The confusion of the modern world is caused by the interactions of many different political

forces. It is simpler to believe it is caused by the Jews than to try to understand the real causes.

Rootless Cosmopolitans

During the 18th and 19th Century nationalism became one of the main forces in European politics. As the Age of Enlightenment and the Age of Revolution undermined the legitimacy of divinely ordained dynasties, the people developed the idea of a nation – a community conceived or “imagined” in three ways: shared culture, limited geographic extent, and governance by the people (Anderson, 2016). Inherent in the concept of a nation was the idea that all its citizens should have equal rights. Nationalism gained its greatest impetus from the revolutions in the United States and France in the 18th century, and from the later Revolutions of 1848 in Europe.

According to the ideals of nationalism, no one should be discriminated against on the basis of their religion. As part of this movement Jewish citizens began therefore to be accepted as equal participants in the new nations (Mendes-Flohr, 1996; Barnavi, 2003, pp 158-9). This emancipation occurred slowly: France in 1791; Prussia in 1812; Belgium in 1830; the Netherlands in 1834 the United Kingdom in 1858; Austria 1867; the United States in 1877 (reviewed in Wikipedia).

Although nationalism wants all its citizens, regardless of their beliefs or background to be equal, it would prefer them to be homogeneous, all believing in the same national ideals. Yet no nation is homogeneous. The success of a nation depends on how it comes together despite its differences.

As nationalism progressed, suspicions about the Jewish people remained. This worry was presaged by the Conte de Clermont‑Tonnere in a speech to France’s new National Assembly in 1789. He initially proposed the principle “that the profession, or manner of worship of a man, can never be motives for depriving him of the Rights of Election.” He then listed some of the arguments against giving citizenship to the Jews and declared them invalid:

It is here I am at tacked by the adversaries of the Jews. That people, say they, are unsociable; usury is enjoined them; they cannot be united with us, either by marriage, or habitual intercourse; they are forbidden our meats, and interdicted our tables. Our armies will never be recruited by Jews; they will never take up arms for the defense of their country. The weightiest of these reproaches is unjust, the others are but specious.

However, he then recognized that Jews may have commitments outside of the nation in which they would be granted full citizenship. They have religious and financial ties to colleagues in other nations. They may wish to be governed by their own laws and judged according to their scriptures. They could thus be a nation within a nation. So he suggested that

you should deny the Jews every thing as a distinct nation, and grant them every thing as individuals.

This idea that Jews were still different from other citizens persisted. The very fact of the diaspora worked against them. With their allegiances to other Jewish communities in other countries, they seemed “cosmopolitan” rather than patriotic. They interfered with a nation’s sense of itself. In the Middle Ages the Jew was assailed because he was not Christian. In the Modern Age he was assailed because he was not truly French or German or Russian. In both cases he was not “one of us.”

The idea of the Jews as “rootless cosmopolitans” was (and is) one of the main tenets of Russian antisemitism. It was basic to the foundation of the Pale of Settlement in Tsarist times and it continued in the socialist regime that followed the Russian Revolution. The following is a description of cosmopolitans from Vissarion Belinsky, a 19th century literary critic who promoted the idea of a truly Russian literature:

The cosmopolitan is a false, senseless, strange and incomprehensive phenomenon, a manifestation in which there is something insipid and vague. He is a corrupt, unfeeling creature, totally unworthy of being called by the holy name of man (quoted in Pinkus, 1988, pp 153-154).

Despite Soviet Russia’s professed goal of the brotherhood of man, the idea of the Jew as a “rootless cosmopolitan” persisted after the Revolution. It came to a frightening culmination in the accusations against the Jewish doctors in 1952-3 (Carfield, 2002). It is frightening to note the similarity between Communist thought and the Fascist idea of Bodenlosigkeit (lack of “ground” in the sense of a place to have roots).

The ideas of nationhood radically changed the lives of many Jews (Arendt, 1951). Intent on proving themselves good citizens of the new nations, they relinquished some of their religious beliefs and behaviors. They became secular. Some even converted to the state religion, hoping to become “assimilated” into general society. Despite all these efforts to become involved as a citizen, the Jews continued to be considered alien. Rather than being welcomed as a compatriots they reviled as pretentious upstarts.

And so many Jews began to think that the only solution was to return to Palestine to found their own new nation of Israel. No longer cosmopolitan they would reclaim their homeland. Zionism would provide Jews with a nation wherein they were not alien (Miller& Ury, 2010).

These new developments made it even more difficult for the Jews who remained in the countries of their birth. Would a Jew support Israel against the interests of the country in which he lives? Zionism raised fears about the allegiance of the Jews, and provided an excuse to exile them from the nations they could not be part of.

So arose the idea that the Jews could never really be part of any non-Jewish nation. This concept was presented by T. S. Eliot (1934) in a series of talks about literary traditions. He describes “tradition:”

What I mean by tradition involves all those habitual actions, habits and customs, from the most significant religious rite to our conventional way of greeting a stranger, which represent the blood kinship of ‘the same people living in the same place.’ (p 18)

He goes on to suggest how tradition should be established and maintained:

What we can do is to use our minds, remembering that a tradition without intelligence is not worth having, to discover what is the best life for us not as a political abstraction, but as a particular people in a particular place; what in the past is worth preserving and what should be rejected; and what conditions, within our power to bring about, would foster the society that we desired. (p. 19)

And then he brings up something that is essential to any great tradition:

The population should be homogeneous; where two or more cultures exist in the same place they are likely either to be fiercely self-conscious or both to become adulterate. What is still more important is unity of religious background; and reasons of race and religion combine to make any large number of free-thinking Jews undesirable. There must be a proper balance between urban and rural, industrial and gricultural development. And a spirit of excessive tolerance is to be deprecated.

The remarks about the free-thinking Jews are strange and terrifying. They are completely out of context in a discussion of the literary traditions of the American South. They clearly reflect the antisemitism of the writer and of his time. In the years subsequent to Eliot’s book, the great liberal democracies of the world refused to accept Jews fleeing from the Nazi regime in Germany for fear that they would pollute their national identities.

Although nationalism fostered the idea of governance by the people, it also promoted war in the pursuit of a nation’s destiny. As Anderson (2016) has pointed out, one of the measures of nationalism’s success is how easily a people will lay down their lives to defend their country. Surely cosmopolitanism is a better ideal.

Conclusion

Human beings unfortunately seem to need to hate. We make an enemy of any one who is different from us. And so we revile those who gave us the Ten Commandments. We need to stop this senseless behavior. The main way forward is to learn abou those who are not us. This will broaden our understanding. With understanding will come tolerance and cooperation. And we should follow ideals that refuse to be limited to one faith or to one nation.

References

Anderson, B. R. O’G. (1983/2016). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Revised Edition. London: Verso.

Arendt, H. (1951, reprinted 1973). The origins of totalitarianism. New York:

Harcourt, Brace Jovanovich.

Bacon, G. (2003). “The House of Hannover”: Gezeirot Tah in modern Jewish historical writing. Jewish History, 17, 179-206.

Bandura, A., Underwood, B., & Fromson, M. E. (1975). Disinhibition of aggression through diffusion of responsibility and dehumanization of victims. Journal of Research in Personality, 9, 253–269.

Barnavi, E. (2003). A historical atlas of the Jewish people: From the time of the patriarchs to the present. New York: Schocken.

Bauer, Y. (2001). A history of the Holocaust. Revised edition. New York:

Franklin Watts.

Baum, S. K. (2012). Antisemitism Explained. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

Beck, A. T. (2002). Prisoners of hate. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40, 209-216.

Beller, S. (2007). Antisemitism: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Bernstein, P. (1951). Jew-hate as a sociological problem. New York: Philosophical Library.

Brewer, M. B. (1999). The psychology of prejudice: Ingroup love or outgroup hate? Journal of Social Issues, 55, 429–435.

Carfield, A. M. (2002), The Soviet “Doctors’ Plot”—50 years on. BMJ,

325 (7378), 1487–9.

Chanes, J. A. (2004). Introduction and Overview. In Antisemitism: A Reference Handbook. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO

Clermont Tonnerre, S. (1790) Translation of a speech, spoken by the Count Clermont Tonnere, Christmas-eve last: on the subject of admitting non-Catholics, comedians, and Jews, to all the privileges of citizens, according to the Declaration of rights. Available at Hathi Trust.

Crossan, J. D. (1995). Who killed Jesus? Exposing the roots of anti-semitism in the Gospel story of the death of Jesus. San Francisco: Harper

Eco, U. (1994). Six walks in the fictional woods. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard

University Press.

Eisner, W. (2005). The plot: The secret story of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. New York: W.W. Norton.

Eliot, T. S. (1934). After strange gods: A primer of modern heresy. London: Faber and Faber.

Foxman, A. H. (2010). Jews and money: The story of a stereotype. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gelbin, C. S., & Gilman, S. L. (2017). Cosmopolitanisms and the Jews. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press

Goldstein, P (2012). A convenient hatred: The history of antisemitism. Brookline, MA: Facing History and Ourselves.

Graves, P. (1921) The truth about “The Protocols”: a literary forgery. The Times (London) August 16, 17, and 18. Reprinted in a pamphlet

Hagemeister, M. (2008). The Protocols of the Elders of Zion: Between history and fiction. New German Critique, 103, 83-95.

Hemon, A. (2008). The Lazarus project. New York: Riverhead Books

Lazare, B. (1903). Antisemitism, its history and causes: Translated from the French. New York: International Library Publishing Co.

Luther, M. (1543/1948) The Jews and Their Lies. Los Angeles: Christian Nationalist Crusade.

Marcus, J. R. (1938). The Jew in the medieval world: A source book: 315-1791. Cincinnati: Union of American Hebrew Congregations.

Marrus, M. R. (1987). The Holocaust in historyToronto: Lester & Orpen Dennys.

Mendes-Flohr, P. (1996). The emancipation of European Jewry. Why was it not self-evident? Studia Rosenthaliana, 30, 7-20.

Milgram, S. (1974) Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York:

Harper.

Miller, M. L., & Ury, S. (2010) Cosmopolitanism: the end of Jewishness? European Review of History, 17, 337-359.

Morse, N. C., & Allport, F. H. (1952). The causation of anti-semitism: an investigation of seven hypotheses. Journal of Psychology 34, 197–233.

Nilus, S., (1906, translated by Marsden, V. E., 1922). Protocols of the learned elders of Zion. Reedy, West Virginia: Liberty Bell Publications

Penkower, M. N. (2004). The Kishinev Pogrom of 1903: A turning point in Jewish history. Modern Judaism, 24, 187–225,

Pinkus, B. (1988). The Jews of the Soviet Union: The history of a national minority. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Prager, D., & Telushkin, J. (1981, reprinted 2003). Why the Jews? The reason for antisemitism. Touchstone Books.

Sartre, J.-P. (translated by Becker, G. J., 1948). Anti-Semite and Jew. New York:

Schocken.

Stavrakopoulou, F. (2004). King Manasseh and child sacrifice: Biblical distortions of historical realities. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Sternberg, R. J. (2003). A duplex theory of hate: Development and application to terrorism, massacres, and genocide. Review of General Psychology 7, 299-328.

Wagner, R. (1850, translated by William Ashton Ellis, 1894). Jews in Music.