Du Fu: Poet, Sage, Historian

Du Fu: Poet, Sage, Historian

Du Fu (712-770 CE) was a poet during a time of great political upheaval in China. He was born near Luoyang and spent much of his young adulthood in the Yanzhou region, finally settling down to a minor official position in Chang’an, the imperial capital. In 755 CE, An Lushan, a disgruntled general, led a rebellion against the Tang dynasty. The emperor was forced to flee Chang’an (modern Xian), and chaos reigned for the next eight years. For more than a year Du Fu was held captive in Chang’an by the rebels. After escaping, he made his way south, living for a time in a thatched cottage in Chengdu, and later at various places along the Yangtze River. His poetry is characterized by an intense love of nature, by elements of Chan Buddhism, and by a deep compassion for all those caught up in the turmoil of history. This is a longer post than usual. I have become fascinated by Du Fu.

Failing the Examinations

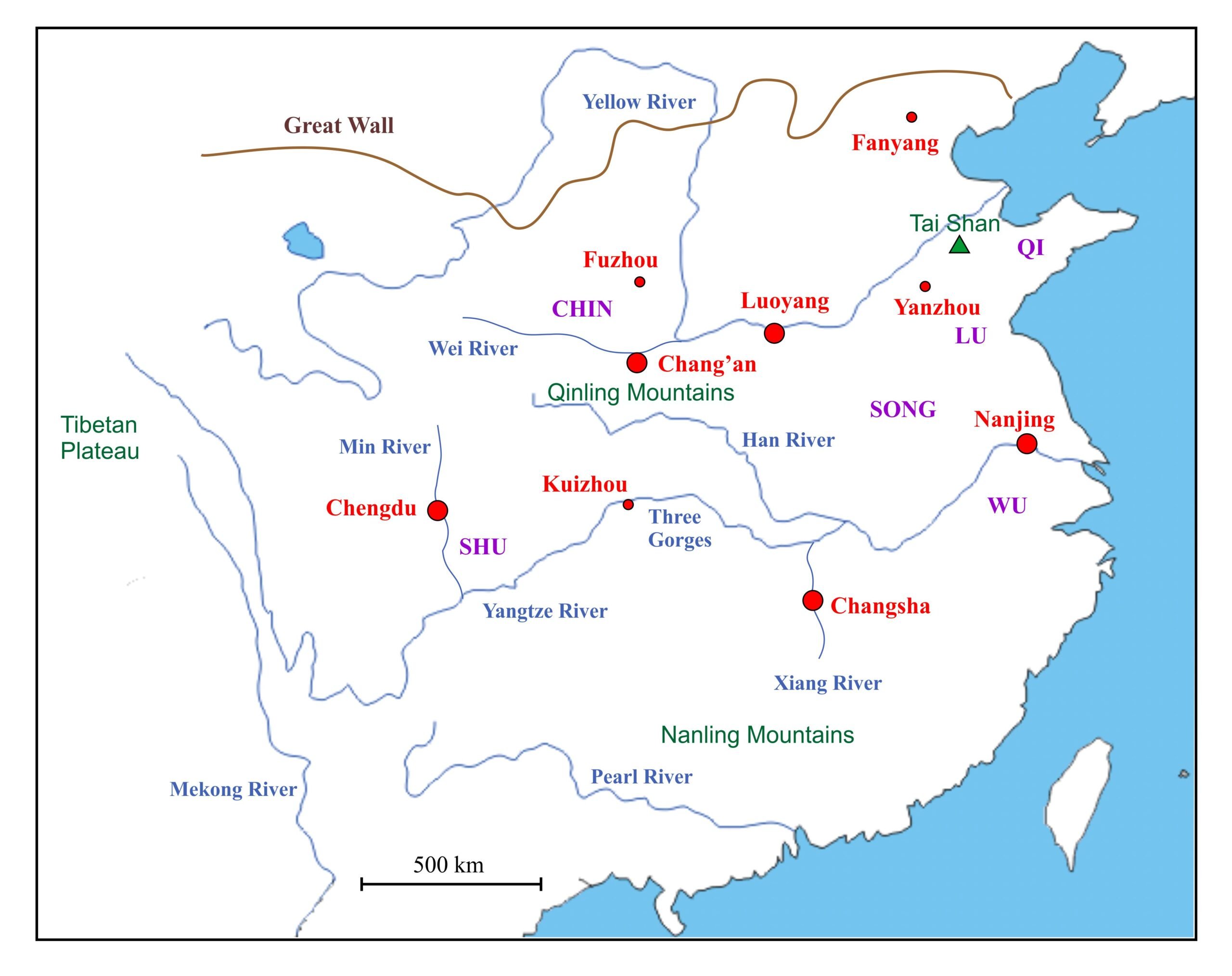

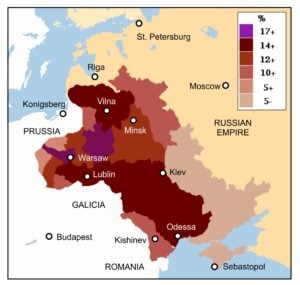

Du Fu (Tu Fu in the Wades Gilles transliteration system, the family name likely deriving from the name of a pear tree) was born in 712 CE near Luoyang, the eastern capital of the Tang Dynasty (Hung, 1952; Owen, 1981). The following map (adapted from Young, 2008, and Collet and Cheng, 2014) shows places of importance in his life:

Du Fu’s father was a minor official. His mother appears to have died during his childhood, and Du Fu was raised by his stepmother and an aunt. Du Fu studied hard, but in 735 CE he failed the jenshi (advanced scholar) examinations. No one knows why: politics and spite may have played their part. He spent the next few years with his father who was then stationed in Yanzhou,

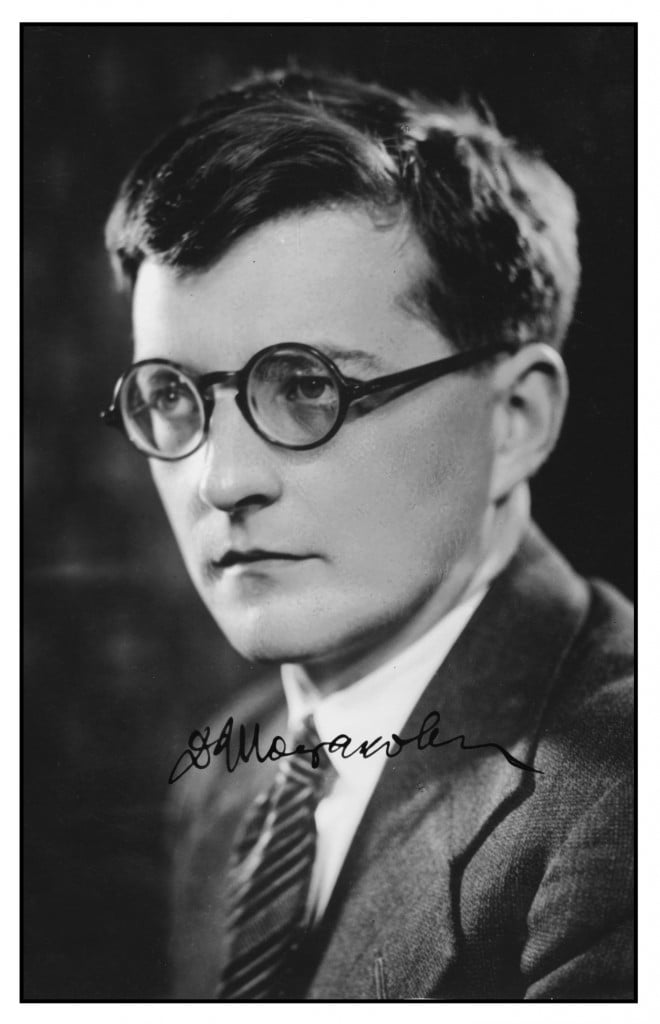

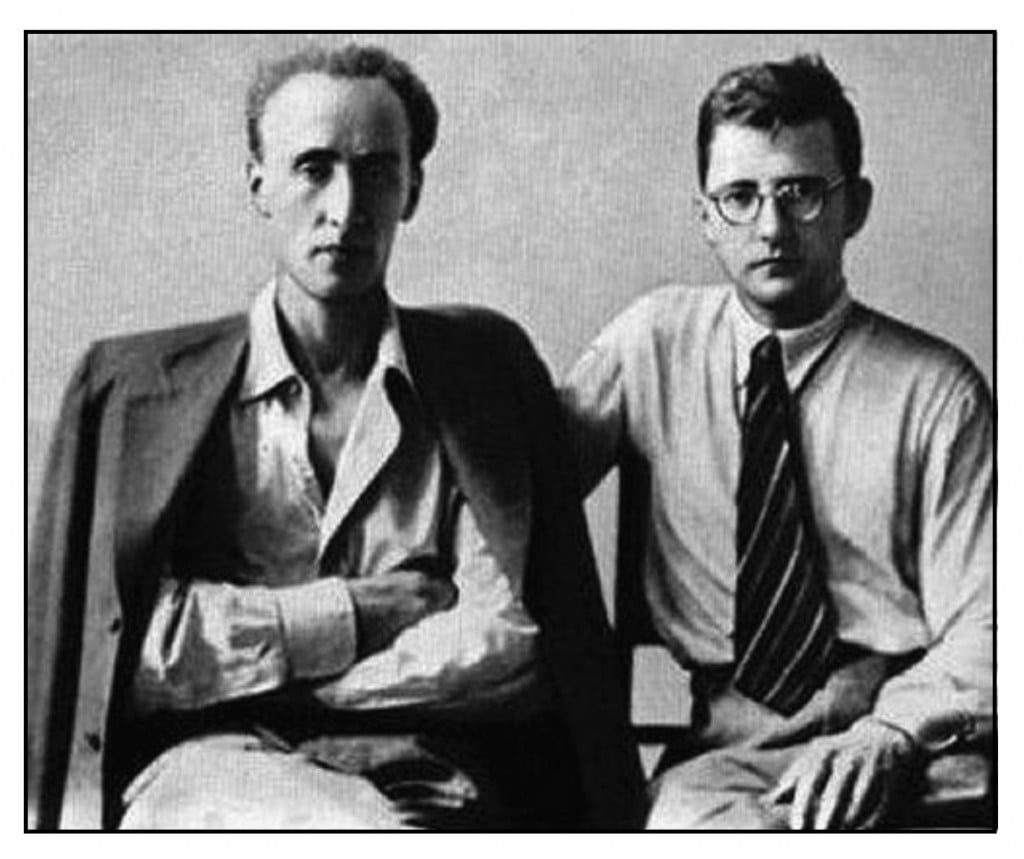

Du Fu met Li Bai (700-762 CE) in 744 CE. Despite the difference in their ages, the two poets became fast friends. However, they were only able to meet occasionally, their lives being separated by politics and war.

Du Fu attempted the jenshi examinations again in 746, and was again rejected. Nevertheless, he was able to obtain a minor position in the imperial civil service in Chang’an. This allowed him to marry and raise a small family.

Taishan

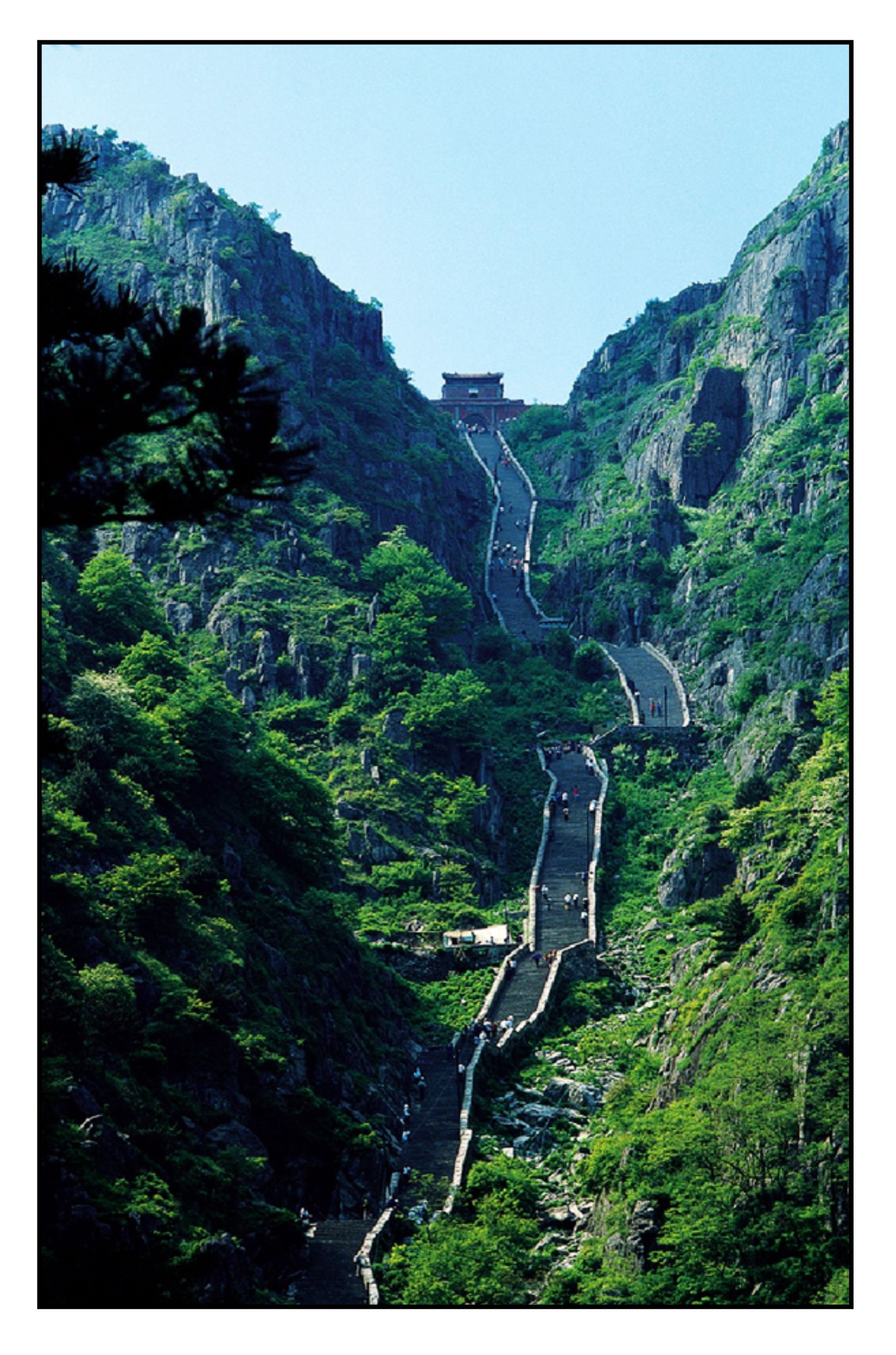

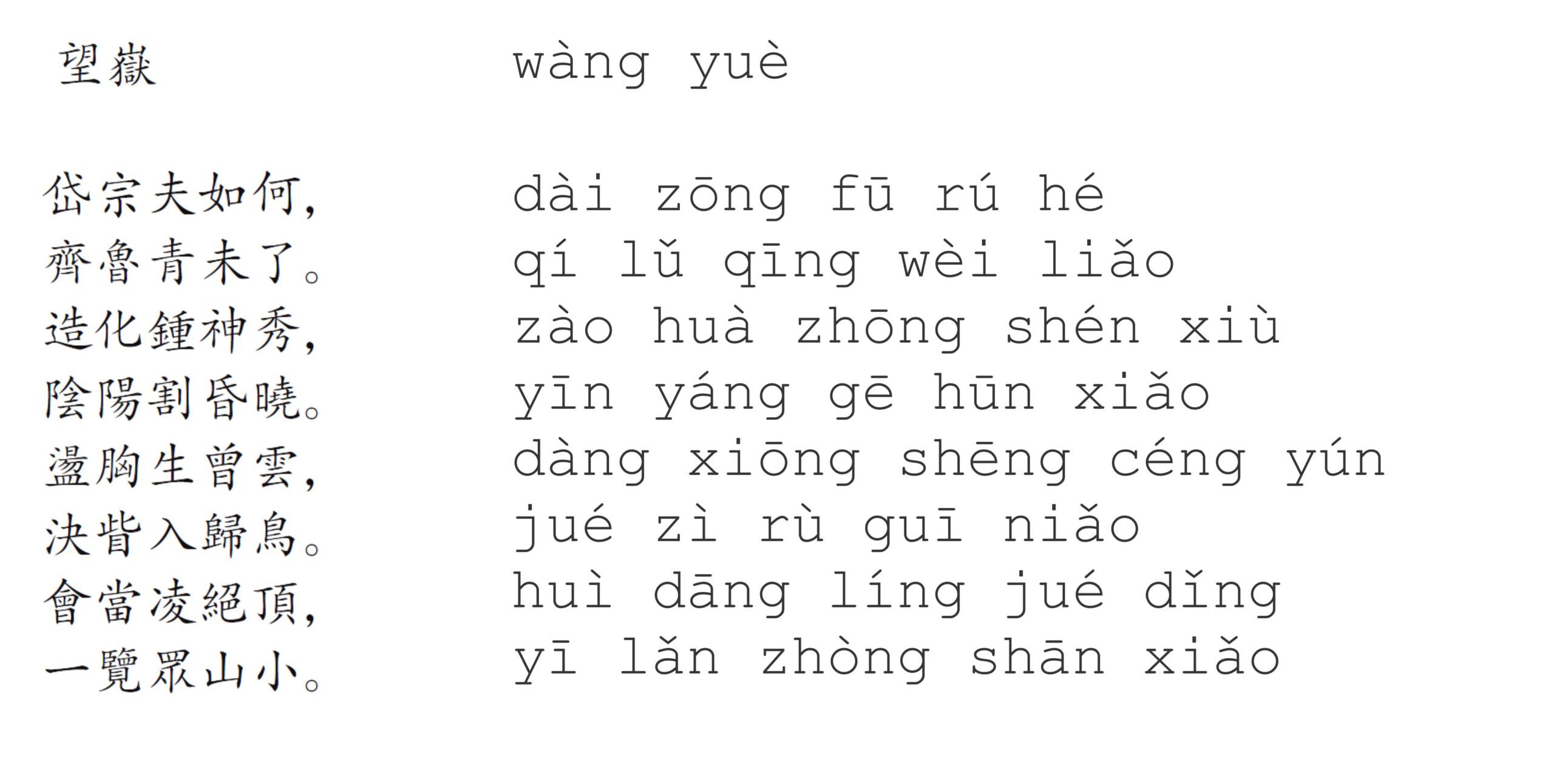

We can begin our examination of Du Fu’s poetry with one of the early poems written during his time in Yanzhou: Gazing on the Peak (737 CE). The peak is Taishan (exalted mountain), located in Northeastern China. Taishan is one of the Five Great Mountains (Wuyue) of ancient China. Today one can reach the summit by climbing up some 7000 steps (see illustration on the right), but in Du Fu’s time the climb would have been more difficult. The following is the poem in printed Chinese characters (Hànzì) and in Pinyin transliteration:

The poem is in the lǜshī (regulated verse) form which requires eight lines (four couplets), with each line containing the same number of characters: 5- or 7-character lǜshī are the most common. Each line is separated into phrases, with a 5-character line composed of an initial 2-character phrase and a final 3-character phrase. The last words of each couplet rhyme. Rhyme in Chinese is based on the vowel sound. Within the lines there were complex rules for the tonality of the sounds (Zong Qi Cai, 2008, Chapter 8; Wai-lim Yip, 1997, pp 171-221). These rules do not always carry over to the way the characters are pronounced in modern Chinese. The following is a reading of the poem in Mandarin (from Librivox).

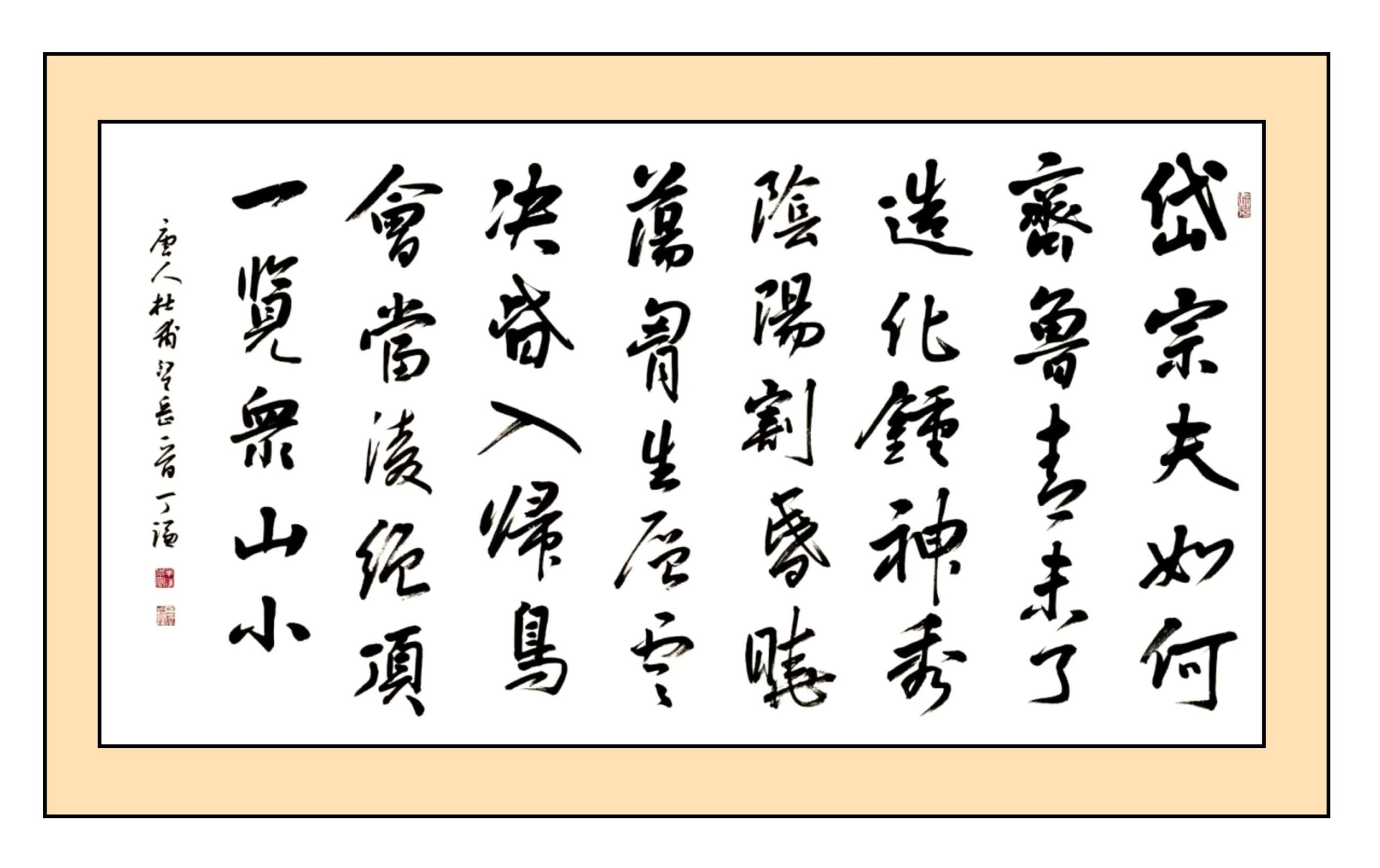

Chinese poetry is directed at both the ear and the eye, and fine calligraphy enhances the appreciations of a poem. Ding Qian has written out Du Fu’s Wàng yuè in beautiful cursive script (going from top down and from left to right):

The following is a character-by-character translation (adapted from Hinton, 2019, p 2):

gaze/behold mountain

Daizong (ancient name for Taishan) then like what

Qi Lu (regions near Taishan) green/blue never end

create change concentrate divine beauty

Yin Yang (Taoist concepts of dark and light) cleave dusk dawn

heave chest birth layer cloud

burst eye enter return bird

soon when reach extreme summit

one glance all mountain small.

And this is the English translation of Stephen Owen (2008, poem 1.2):

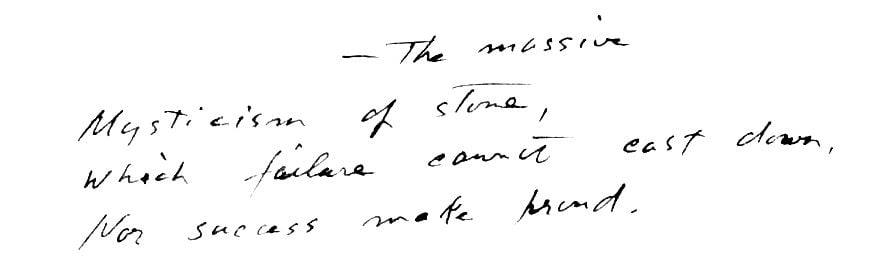

Gazing on the Peak

And what then is Daizong like? —

over Qi and Lu, green unending.

Creation compacted spirit splendors here,

Dark and Light, riving dusk and dawn.

Exhilarating the breast, it produces layers of cloud;

splitting eye-pupils, it has homing birds entering.

Someday may I climb up to its highest summit,

with one sweeping view see how small all other mountains are

The interpretation of the poem requires some knowledge of its allusions. In the fourth line, Du Fu is referring to the taijitu symbol of Taoism (illustrated on the right) that contrasts the principles of yin (dark, female, moon) and yang (light, male, sun). Du Fu proposes that Taishan divides the world into two ways of looking. Some have suggested that the taijitu symbol originally represented the dark (north) side and the light (south) side of a mountain, and this idea fits easily with the poem.

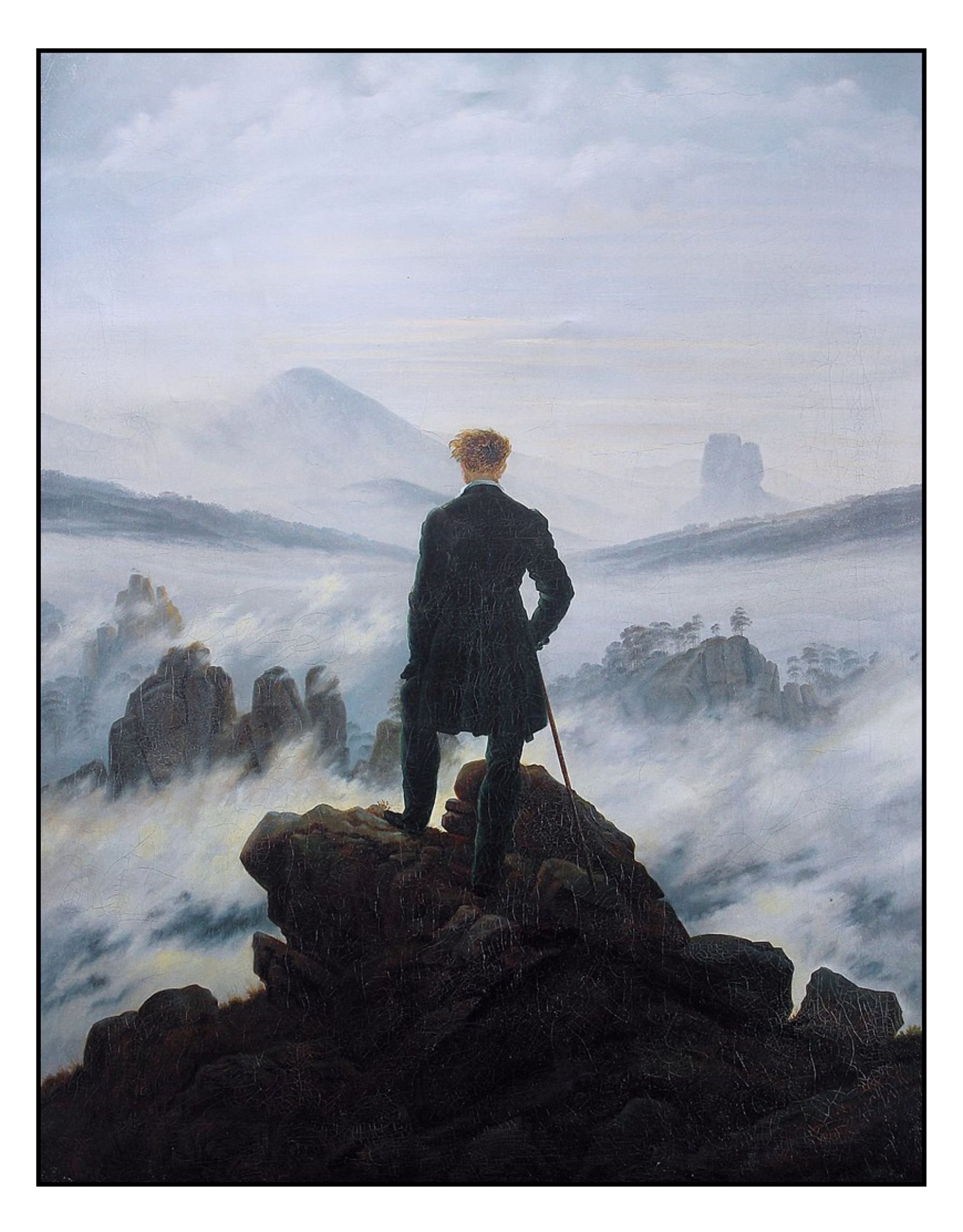

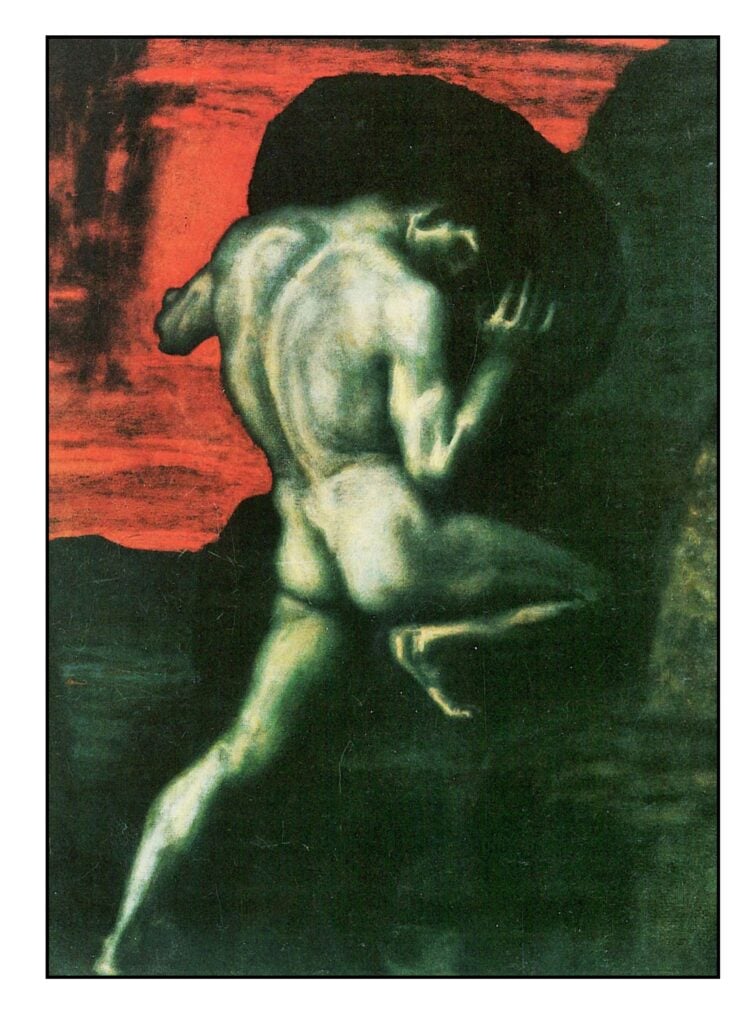

All translators have had difficulty with the third couplet (reviewed by Hsieh, 1994). My feeling is that Du Fu is noticing layers of clouds at the mountain’s upper reaches – the chest if one considers the mountain like a human body – and birds swooping around the peaks – where the eye sockets of the body would be. However, it is also possible that Du Fu is breathing heavily from the climb and that his eyes are surprised by the birds. Perhaps both meanings are valid, with Du Fu and the mountain becoming one. Du Fu may have been experiencing the meditative state of Chan Buddhism, with a mind was “wide-open and interfused with this mountain landscape, no distinction between subjective and objective” (Hinton, 2019, p 6). One might also consider Du Fu’s mental state: at the time he wrote this poem he had just failed the jenshi exams. This might have caused some breast-beating and tears, as well as his final resolve to climb the mountain and see how small all his problems actually were.

The last couplet refers to Mencius’ description of the visit of Confucius to Taishan (Mengzi VIIA:24):

He ascended the Tai Mountain, and all beneath the heavens appeared to him small. So he who has contemplated the sea, finds it difficult to think anything of other waters, and he who has wandered in the gate of the sage, finds it difficult to think anything of the words of others.

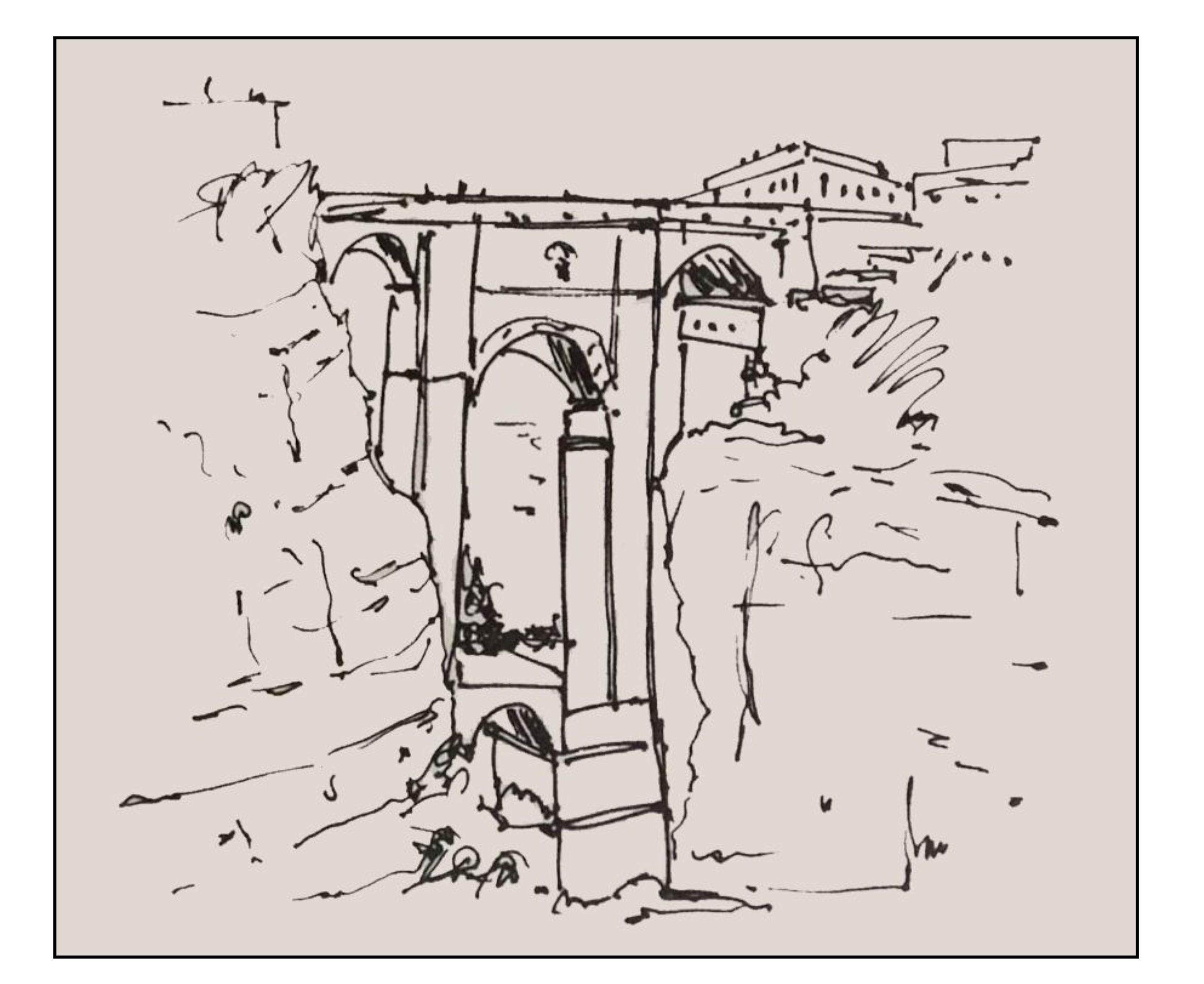

Zhang’s Hermitage

During his time in Yanzhou Du Fu visited a hermit named Zhang near the Stonegate Mountain, one of the lesser peaks near Taishan. Zhang was likely a follower of the new Chan Buddhism, which promoted meditation as a means to empty the mind of suffering and allow the universal life force to permeate one’s being. Buddhism first came to China during the Han dynasty (206BCE – 220CE). Since many of the concepts of Buddhism were similar to those of Taoism, the new religion spread quickly (Hinton, 2020). A type of Buddhism that stressed the role of meditation began to develop in the 6th Century CE, and called itself chan, a Chinese transcription of the Sanskrit dhyana (meditation). In later years this would lead to the Zen Buddhism of Japan. There are many allusions to Buddhism and especially to Chan ideas in Du Fu’s poetry (Rouzer, 2020; Zhang, 2018)

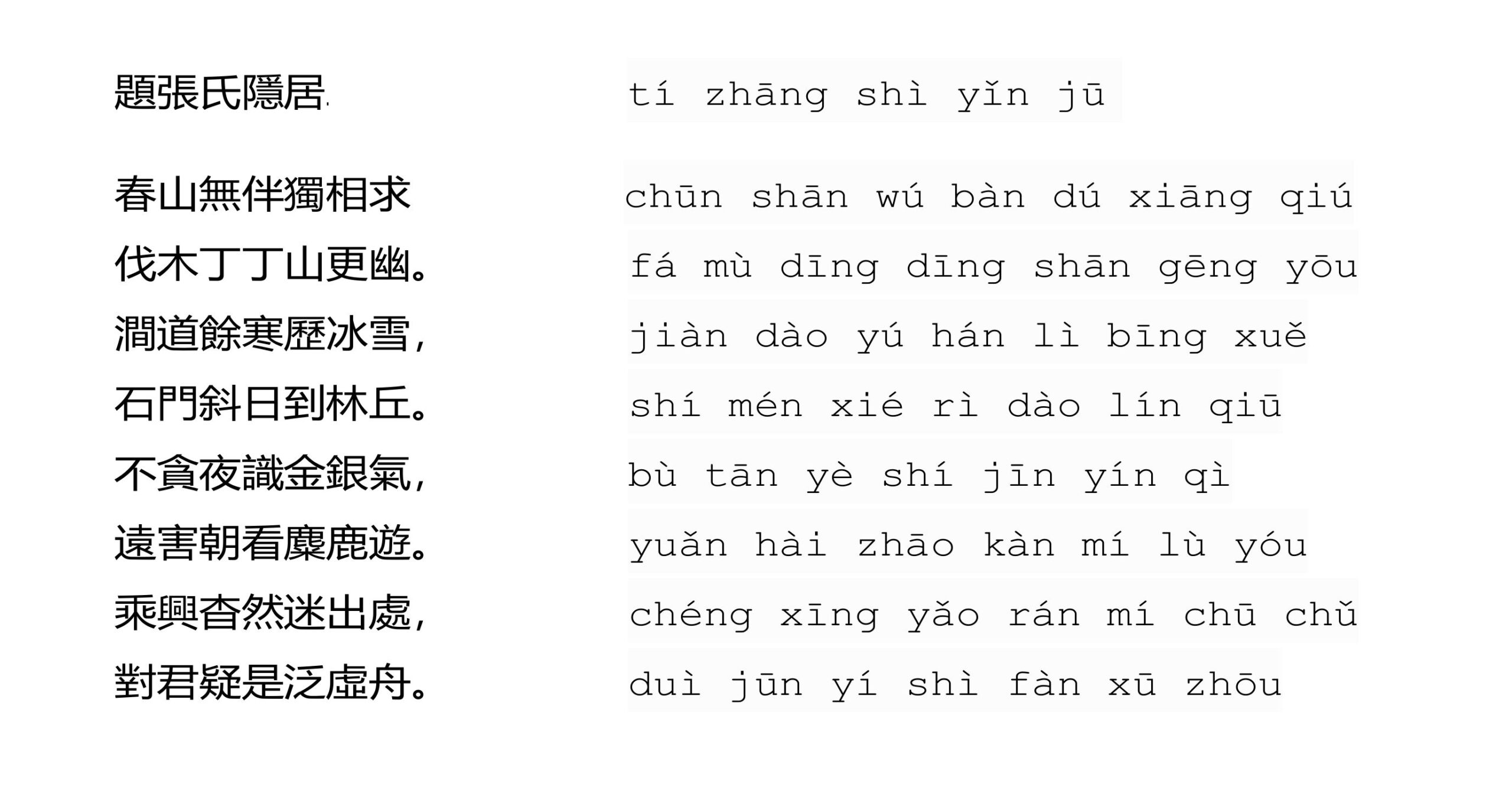

Du Fu reportedly wrote the following poem on one of the walls of Zhang’s hermitage. The poem is a seven-character lǜshī. The following is the poem in Chinese characters (Owen, 2008, poem 1.4) and in pinyin:

The following is a character-by-character translation (adapted from Hinton, 2019, p 22):

inscribe Zhang family recluse house

spring mountain absence friend alone you search

chop tree crack crack mountain again mystery

creek pathway remnant cold pass ice snow

stone gate slant sun reach forest place

no desire night know gold silver breath/spirit

far injure morning see deer deer wander

ride burgeon dark thus confuse leave place

facing you suspect this drift empty boat.

And this is a translation by Kenneth Rexroth (1956):

Written on the Wall at Chang’s Hermitage

It is Spring in the mountains.

I come alone seeking you.

The sound of chopping wood echos

Between the silent peaks.

The streams are still icy.

There is snow on the trail.

At sunset I reach your grove

In the stony mountain pass.

You want nothing, although at night

You can see the aura of gold

And silver ore all around you.

You have learned to be gentle

As the mountain deer you have tamed.

The way back forgotten, hidden

Away, I become like you,

An empty boat, floating, adrift.

Notable in the poem is the idea of wú (third character) which can be translated as “absence, nothing, not” (Hinton, 2019, p 24) This is an essential concept of Chan Buddhism – the emptying of the mind so that it can become a receptacle for true awareness. The third and fourth characters of the first line might be simply translated as “alone (without a friend),” but one might also venture “with absence as a companion” or “with an empty mind.” This fits with the image of the empty boat at the end of the poem.

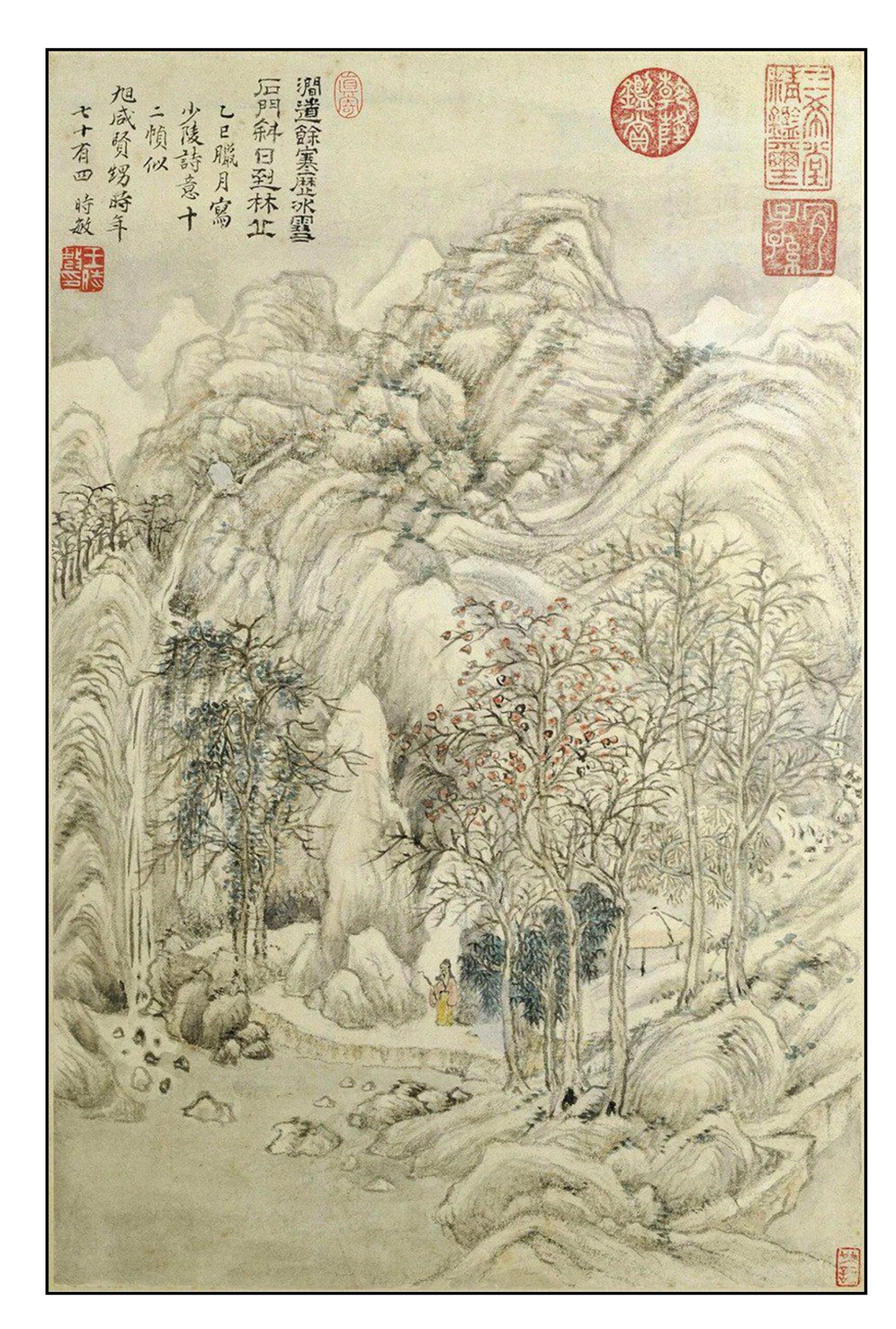

Zheng Qian, a drinking companion of Li Bai and Du Fu, suggested the idea of combining poetry, painting and calligraphy. The Emperor was impressed and called the combination sānjué (three perfections) (Sullivan, 1974). Li Bai and Du Fu likely tried their hand at painting and calligraphy but no versions of their sānjué efforts have survived. The Ming painter and calligrapher Wang Shimin (1592–1680 CE) illustrated the second couplet of Du Fu’s poem from Zhang’s hermitage in his album Du Fu’s Poetic Thoughts now at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

The An Lushan Rebellion

Toward the end 755 CE, An Lushan, a general on the northern frontier rebelled against the empire and captured the garrison town of Fanyang (or Jicheng) located in what is now part of Beijing. Within a month the rebels captured Luoyang. The emperor and much of his court fled Chang’an, travelling through the Qinling Mountains to find sanctuary in the province of Shu. The city of Chang’an fell to the rebels in the middle of 756 CE.

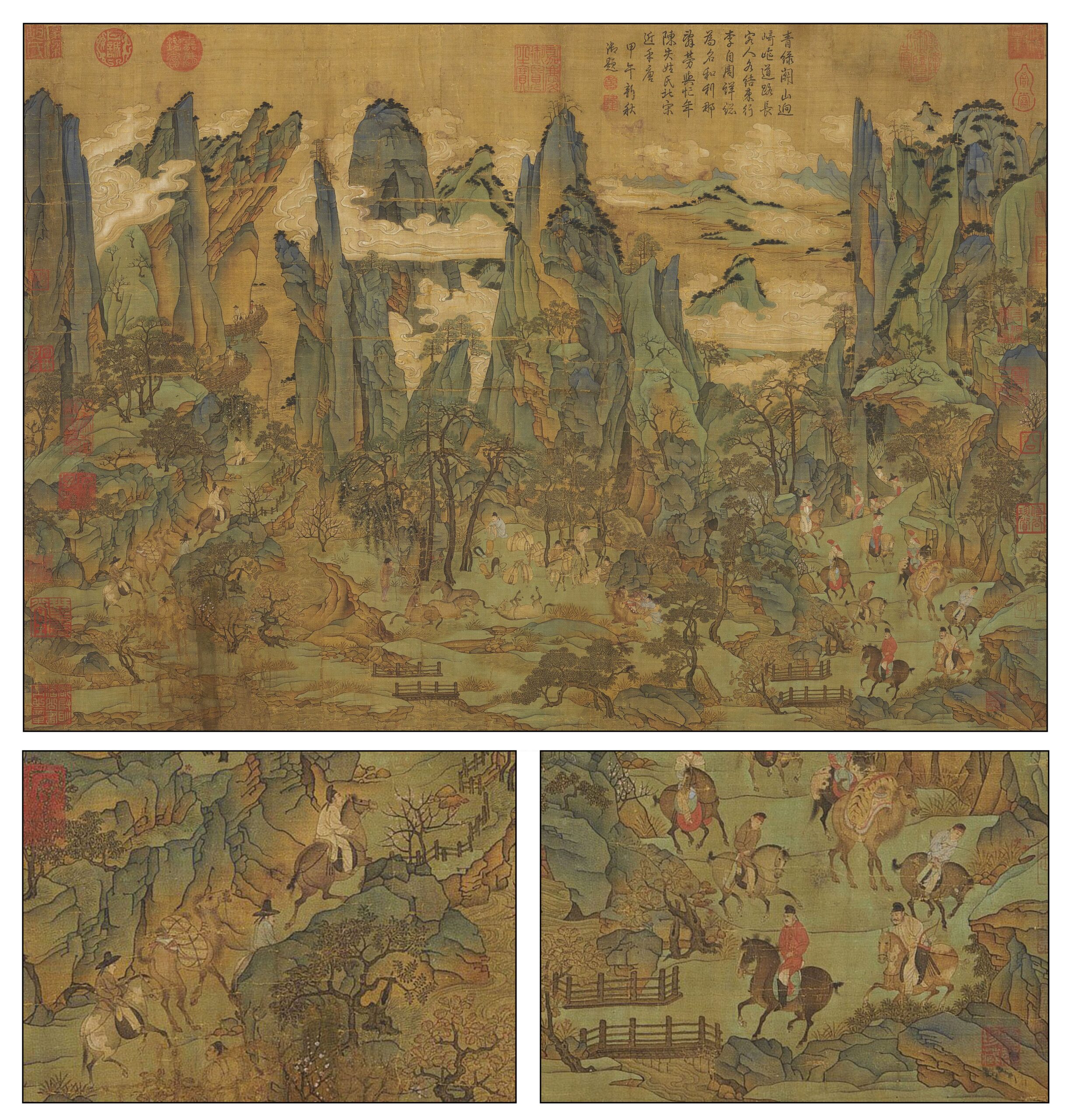

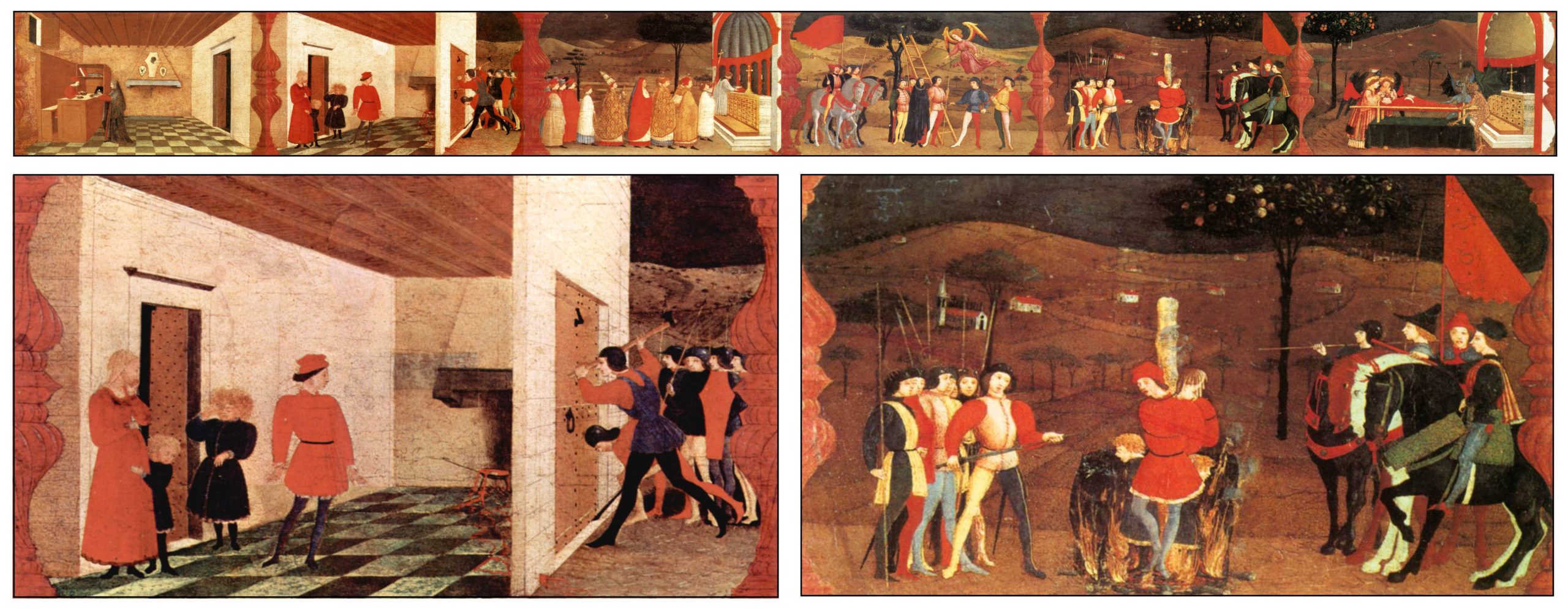

Below is shown a painting of Emperor Ming-Huang’s Flight to Shu. Though attributed to the Tang painter Li Zhaodao (675-758 CE), this was actually painted in his style several hundred years later during the Song Dynasty. Shu is the ancient name for what is now known as Sichuan province. This masterpiece of early Chinese painting is now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Two enlargements are included: the emperor with his red coat is shown at the lower right; at the lower left advance members of his entourage begin climbing the mountain paths.

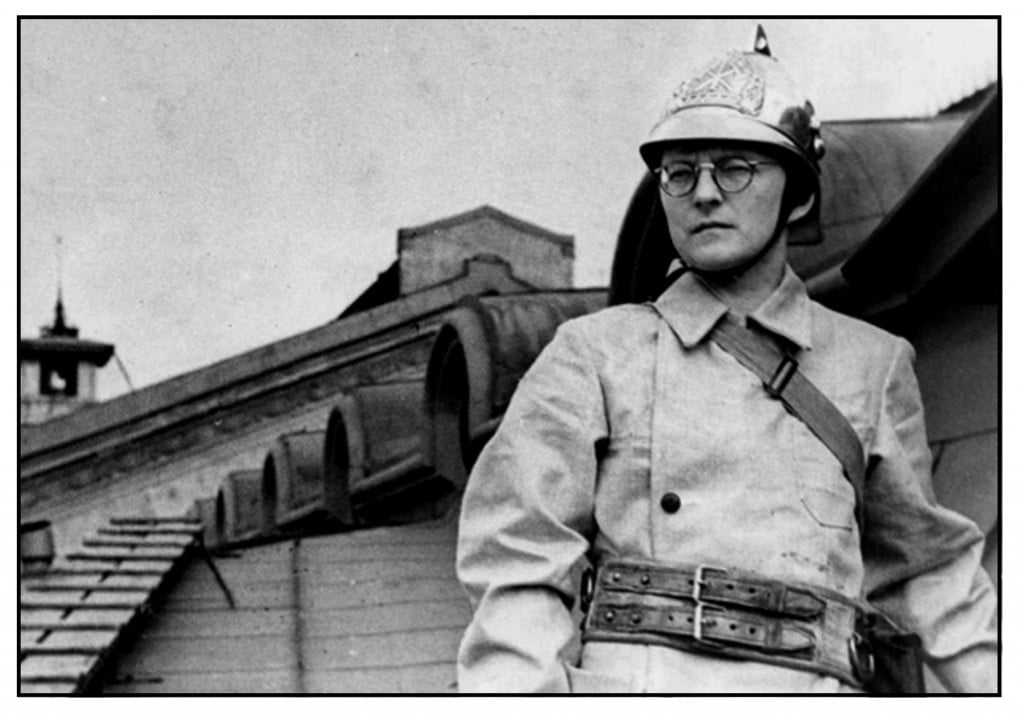

The rebellion lasted for eight long years. The northern part of the country was devastated. Death from either war or famine was widespread. Censuses before and after the rebellion suggested a death toll of some 36 million people, making it one of the worst catastrophes in human history. However, most scholars now doubt these numbers and consider the death toll as closer to 13 million. Nevertheless, it was a murderous time.

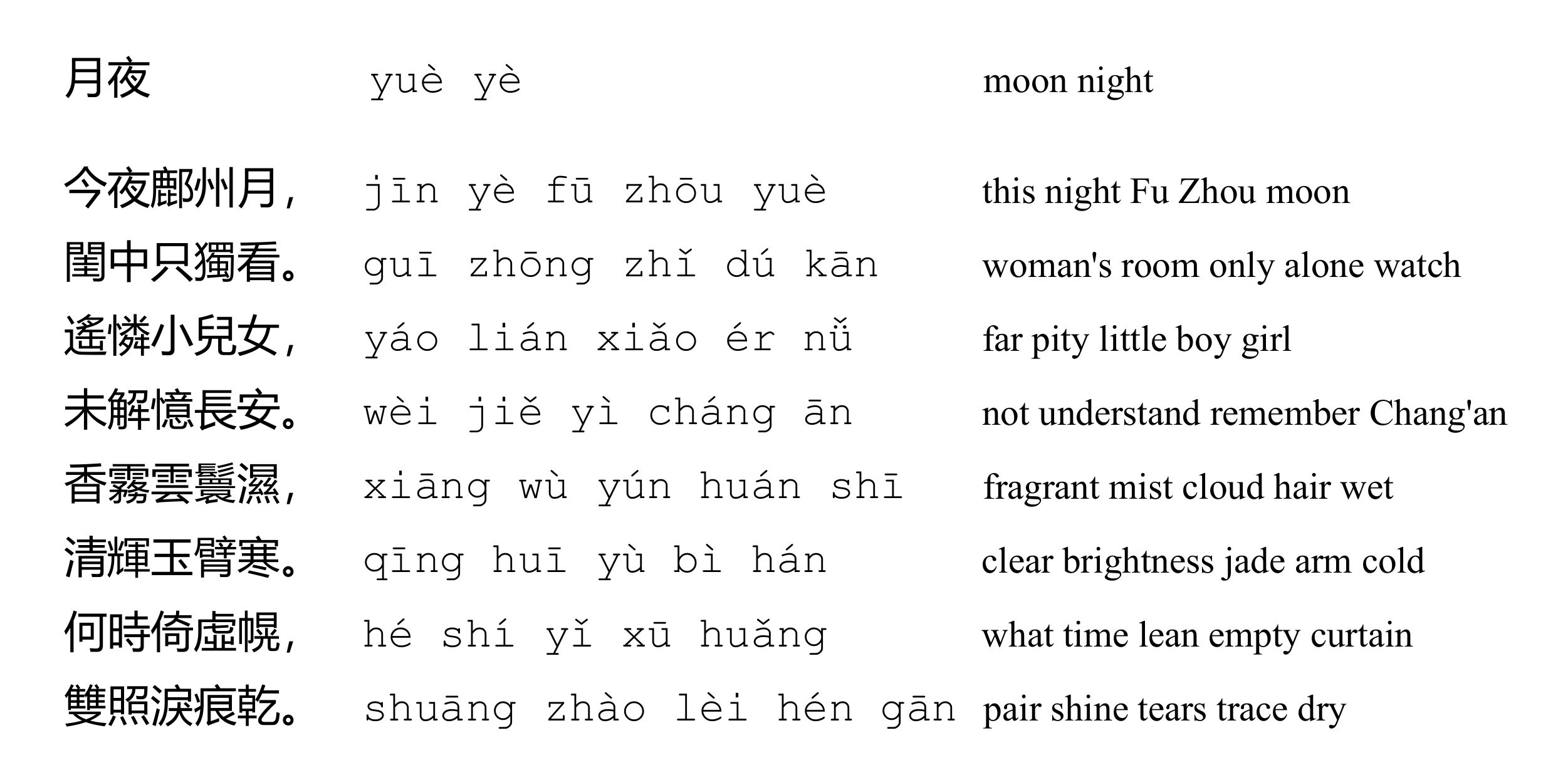

Moonlit Night

At the beginning of the rebellion, Du Fu managed to get his family to safety in the northern town of Fuzhou, but he was himself held captive in Chang’an. Fortunately, he was not considered important enough to be executed, and he finally managed to escape in 757 CE. The following shows a poem from 756 CE in characters (Owen, 2008, poem 4.18), pinyin transcription, and character-by-character translation (Alexander, 2008):

The following is a reading of the poem from Librivox:

Vikam Seth (1997) translated the poem keeping the Chinese rhyme scheme: the last character rhymes for all four couplets:

Moonlit Night

In Fuzhou, far away, my wife is watching

The moon alone tonight, and my thoughts fill

With sadness for my children, who can’t think

Of me here in Changan; they’re too young still.

Her cloud-soft hair is moist with fragrant mist.

In the clear light her white arms sense the chill.

When will we feel the moonlight dry our tears,

Leaning together on our window-sill?

Alec Roth wrote a suite of songs based on Vikam Seth’s translations of Du Fu. The following is his setting for Moonlit Night with tenor Mark Padmore:

David Young (2008) provides a free-verse translation:

Tonight

in this same moonlight

my wife is alone at her window

in Fuzhou

I can hardly bear

to think of my children

too young to understand

why I can’t come to them

her hair

must be damp from the mist

her arms

cold jade in the moonlight

when will we stand together

by those slack curtains

while the moonlight dries

the tear-streaks on our faces?

The poem may have been written or at least conceived during the celebration of the full moon in the autumn. Families customarily viewed the moon together and Du Fu imagines his wife viewing the moon alone. The mention of the wife’s chamber in the second line may refer to either her actual bedroom or metonymically to herself as the inmost room in Du Fu’s heart (Hawkes, 1967). David Young (2008) remarks that this may be “the first Chinese poem to address romantic sentiments to a wife,” instead of a colleague or a courtesan.

David Hawkes (1967) notes the parallelism of the third couplet:

‘fragrant mist’ parallels ‘clear light,’ ‘cloud hair’ parallels ‘jade arms,’ and ‘wet’ parallels ‘cold’

Spring View

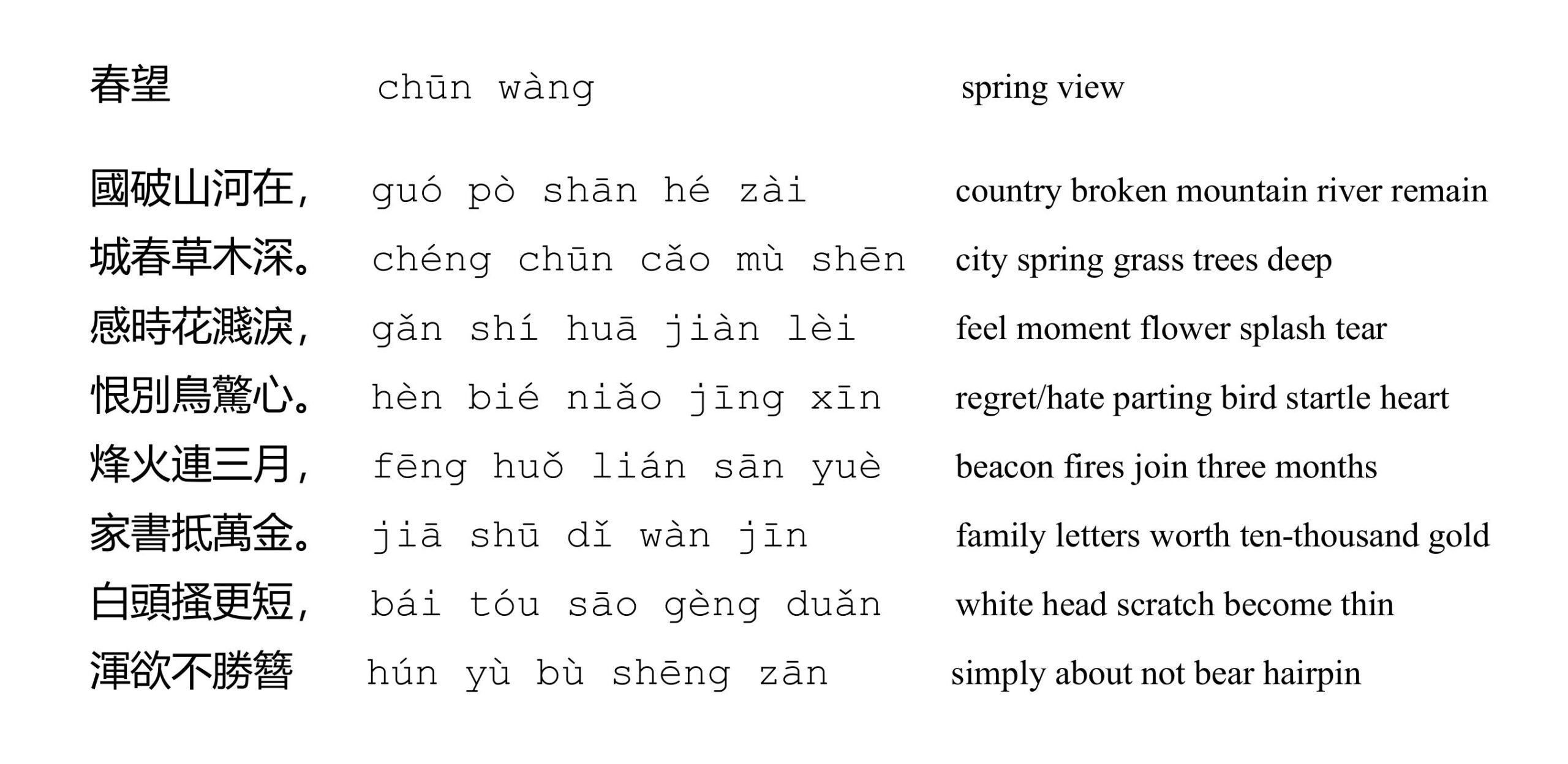

Spring View (or Spring Landscape), the most famous poem written by Du Fu in Chang’an during the rebellion, tells how nature persists despite the ravages of effects of war and time. Subjective emotions and objective reality become one. The character wàng (view, landscape) can mean both the act of perceiving or what is actually perceived. In addition, it can sometimes mean the present scene or what is to be expected in the future (much like the English word “prospect”). The illustration below shows the text in Chinese characters (Owen, 2008, poem 4.25), in pinyin and in a character-by-character translation (adapted from Hawkes, 1967, Alexander, 2008, and Zong-Qi Cai, 2008):

The following is a reading of the poem from the website associated with How to Read Chinese Poetry (ZongQi-Cai, 2008, poem 8.1):

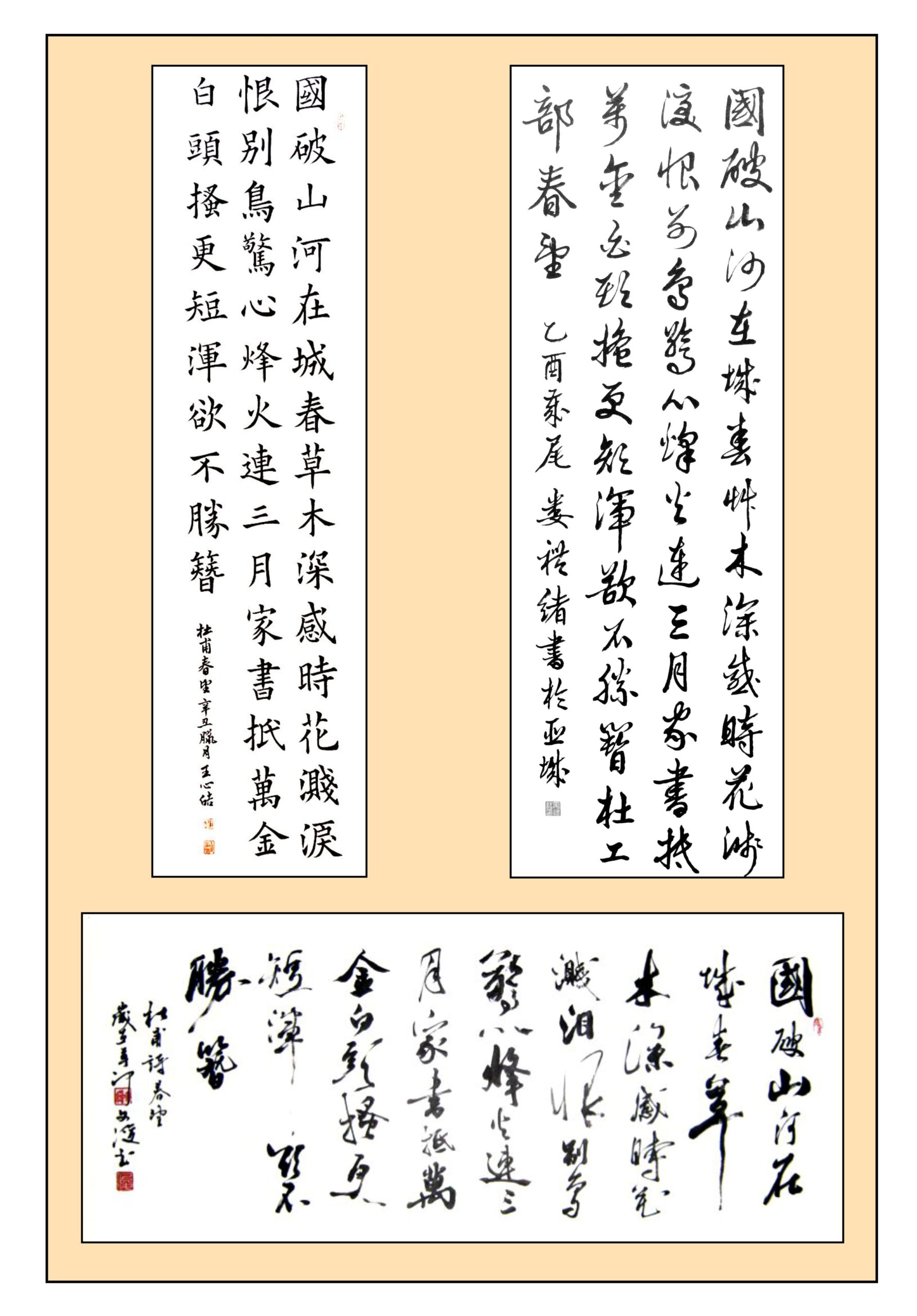

The next illustration shows the poem as written by three calligraphers. All versions read from top down and from right to left. On the left is standard script by Anita Wang; on the right the calligraphy by Lii Shiuh Lou is gently cursive. At the bottom the calligraphy by an anonymous calligrapher is unrestrained: it accentuates the root of the growing grass (8th character) and the radicals that compose the character for regret/hate (16th character) fly apart.

The following are two translations, the first by David Hinton, which uses an English line of a constant length to approximate the Chinese 5-character line (2020a):

The country in ruins, rivers and mountains

continue. The city grows lush with spring.

Blossoms scatter tears for us, and all these

separations in a bird’s cry startle the heart.

Beacon-fires three months ablaze: by now

a mere letter’s worth ten thousand in gold,

and worry’s thinned my hair to such white

confusion I can’t even keep this hairpin in.

A second translation, with preservation of the rhyme scheme and phrasal structure, is by Keith Holyoak (2015)

The state is in ruin;

yet mountains and rivers endure.

In city gardens

weeds run riot this spring.

These dark times

move flowers to sprinkle tears;

the separations

send startled birds on the wing.

For three months now

the beacon fires have burned;

a letter from home

would mean more than anything.

I’ve pulled out

so many of my white hairs

too few are left

to hold my hatpin in!

The second couplet has been interpreted in different ways. Most translations (including the two just quoted) consider it as representing nature’s lament for the evil times. For example, Hawkes (1967) suggests that “nature is grieving in sympathy with the beholder at the ills which beset him.” However, Michael Yang (2016) proposes that “In times of adversity, nature may simply be downright uncaring and unfriendly, thereby adding to the woes of mankind.” He translates the couplet

Mourning the times, I weep at the sight of flowers;

Hating separation, I find the sound of birds startling.

The last two lines of the poem refer the hair-style of the Tang Dynasty: men wore their hair in a topknot, and their hats were “anchored to their heads with a large hatpin which passed through the topknot of hair” (Hawkes, 1967). Most interpreters have been struck by the difference between the solemn anguish of the poem’s first six lines, and the self-mockery of the final couplet (Hawkes, 1967, p 46; Chou, 1995, p 115). This juxtaposition of the tragic and the pitiable accentuates the poet’s bewilderment.

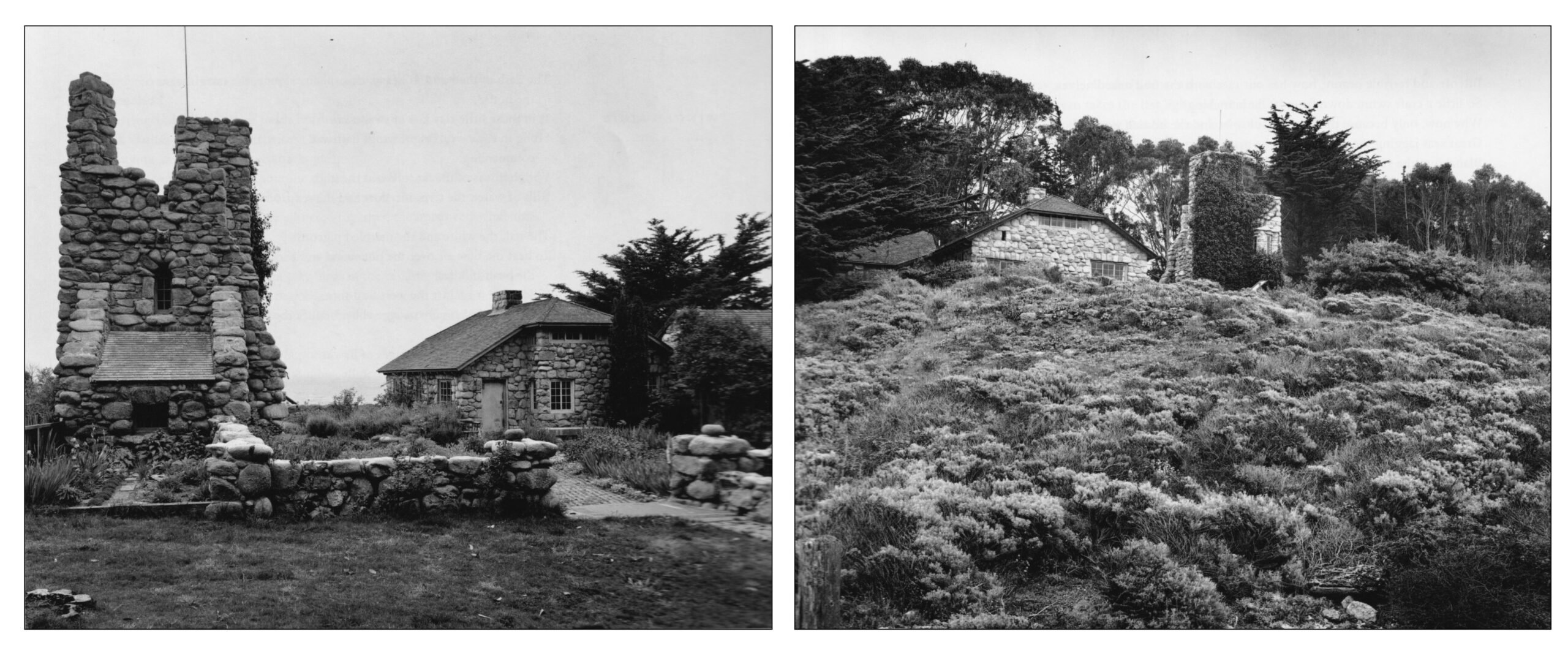

The Thatched Cottage

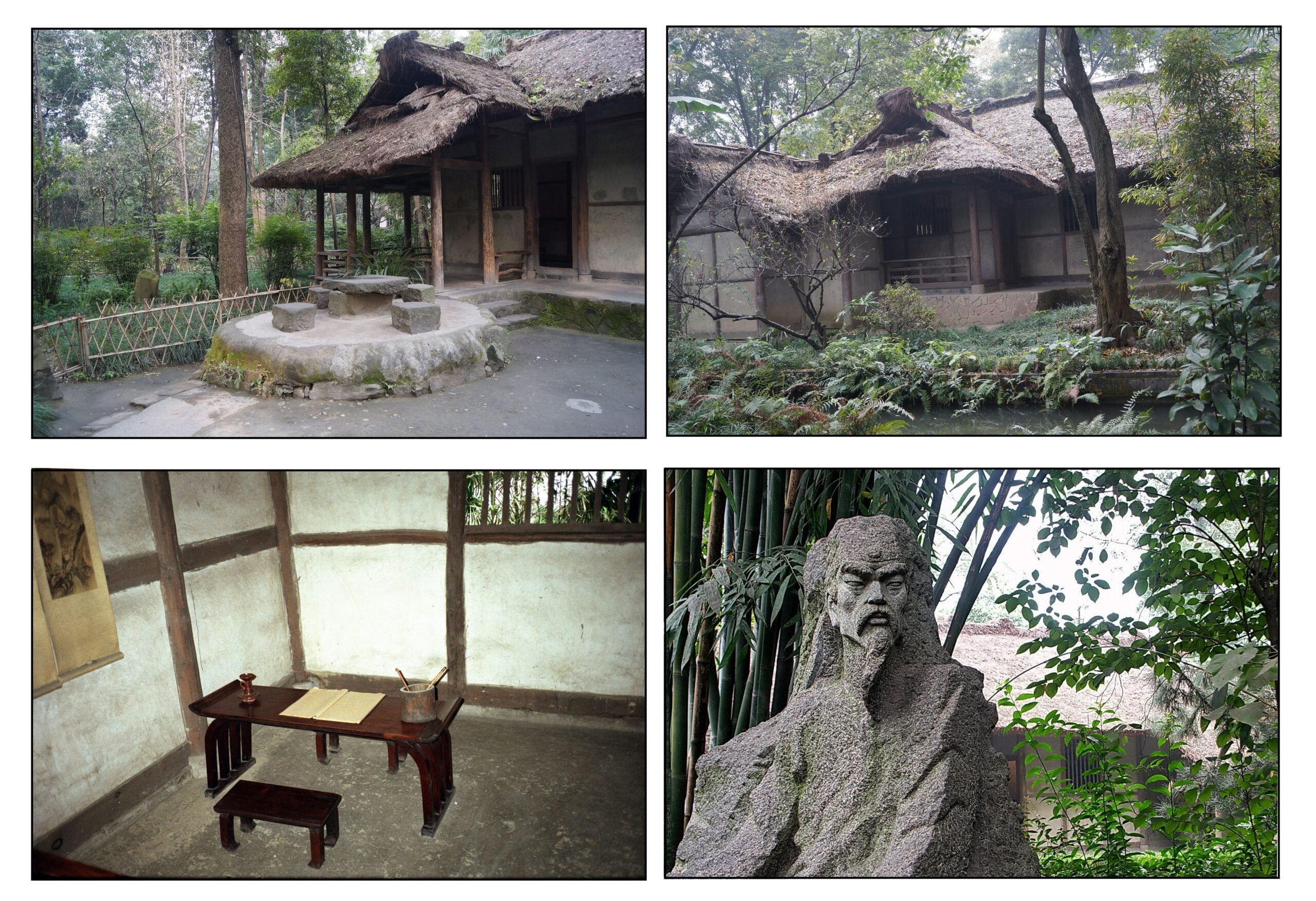

Disillusioned by the war and by the politics of vengeance that followed, Du Fu and his family retired to a thatched cottage in Chengdu, where he lived from 759-765. A replica of this cottage has been built there in a park celebrating both Du Fu and Chinese Poetry:

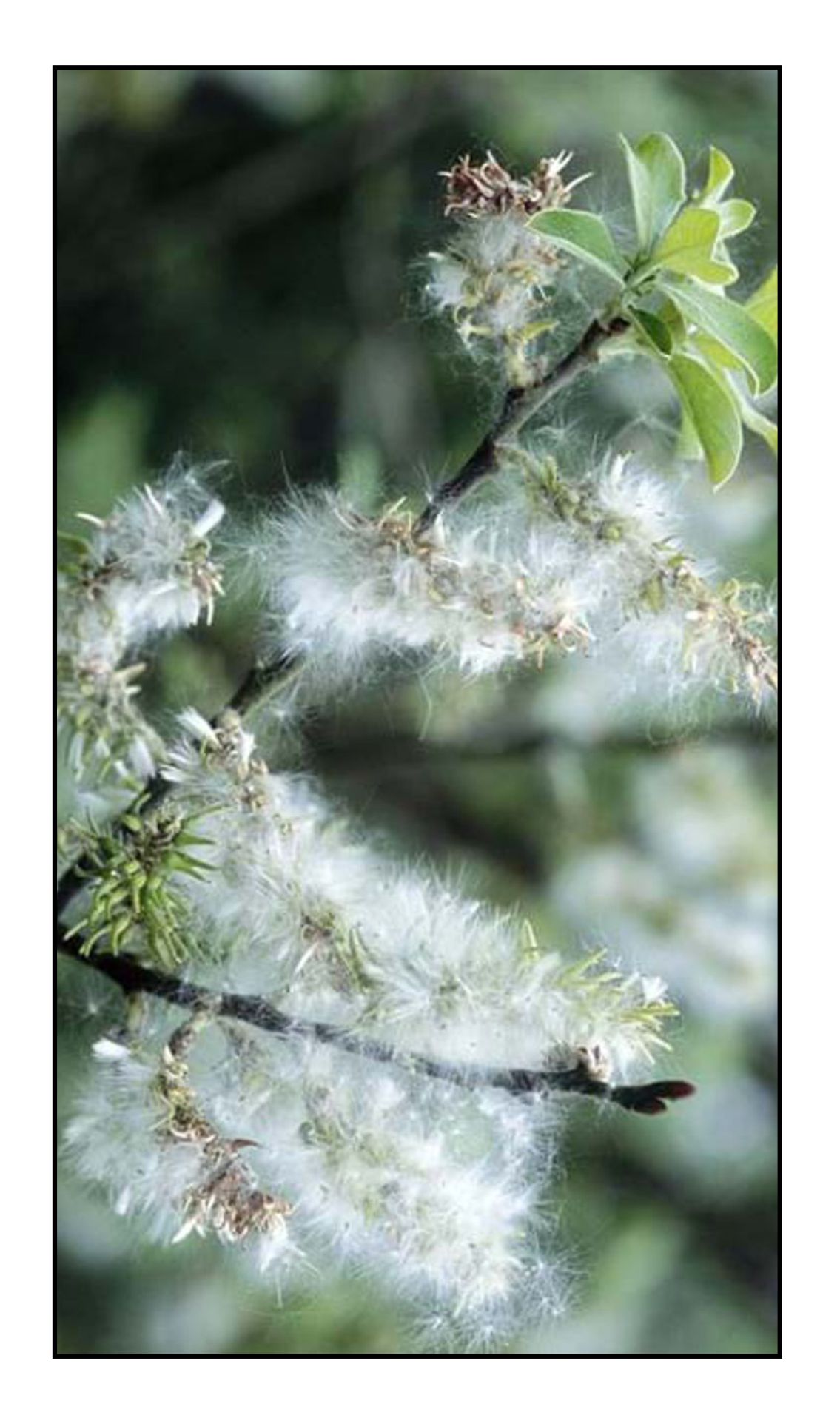

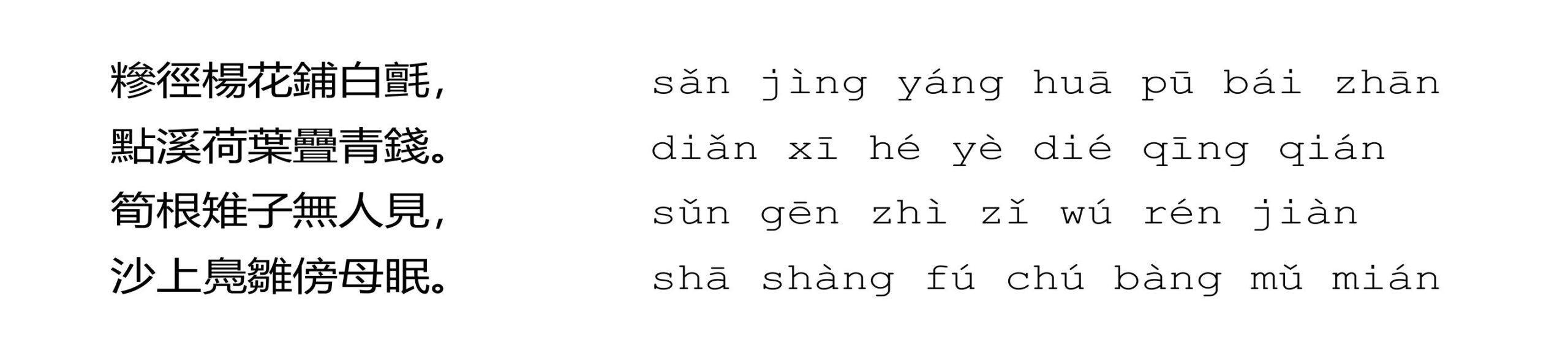

Many of the poems that Du Fu wrote in Chengdu celebrated the simple joys of nature. He often used isolated quatrains to find parallels between his emotions and the world around him. This brief form called juéjù (curtailed lines) was widely used by his colleagues Li Bai (701–762) and Wang Wei (699–759). The form consists of two couplets juxtaposed in meaning and rhyming across their last character (Wong, 1970; Zong-Qi Cai, 2008, Chapter 10). The following poem (Owen, 2008, poem 9.63) describing willow-catkins (illustrated on the right) and sleeping ducks gives a deep feeling of peace. These are the Chinese characters and pinyin transcription followed by the character-by-character translation (Alexander, 2008):

grain path poplar/willow blossom pave white carpet

little stream lotus leaves pile green money

bamboo shoot root sprout no person see

sand on duckling beside mother sleep

The following translation is by Burton Watson (2002):

Willow fluff along the path spreads a white carpet;

lotus leaves dot the stream, plating it with green coins.

By bamboo roots, tender shoots where no one sees them;

on the sand, baby ducks asleep beside their mother.

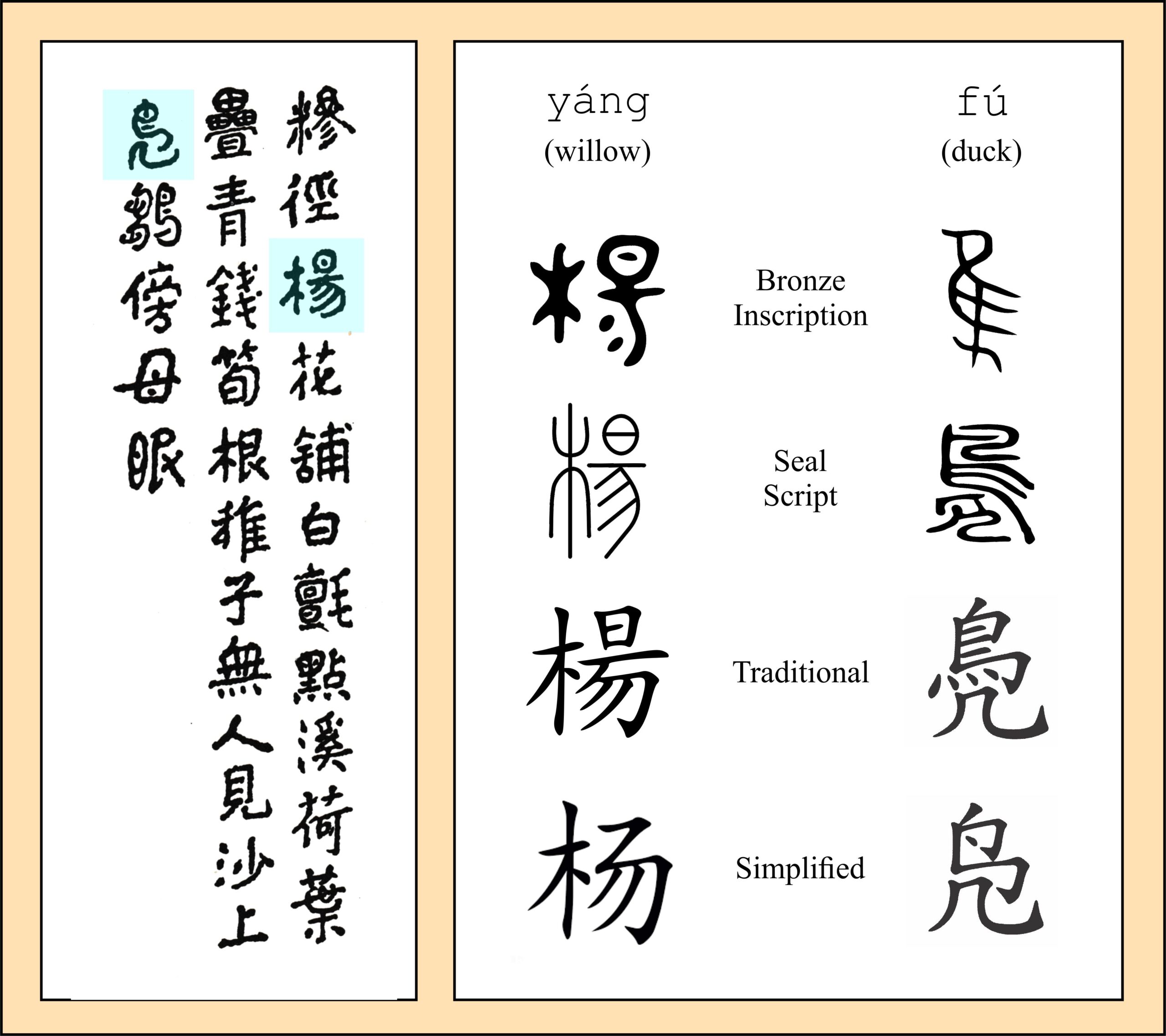

Shui Chien-Tung provided the following calligraphy for the poem (Cooper, 1973). He used aspects of the ancient scripts (circles, curves and dots) in some of the characters to give a sense of simplicity and timelessness. The illustration shows the calligraphy of the poem on the left and the evolution of the characters yáng (willow, poplar) and fú (duck) on the right.

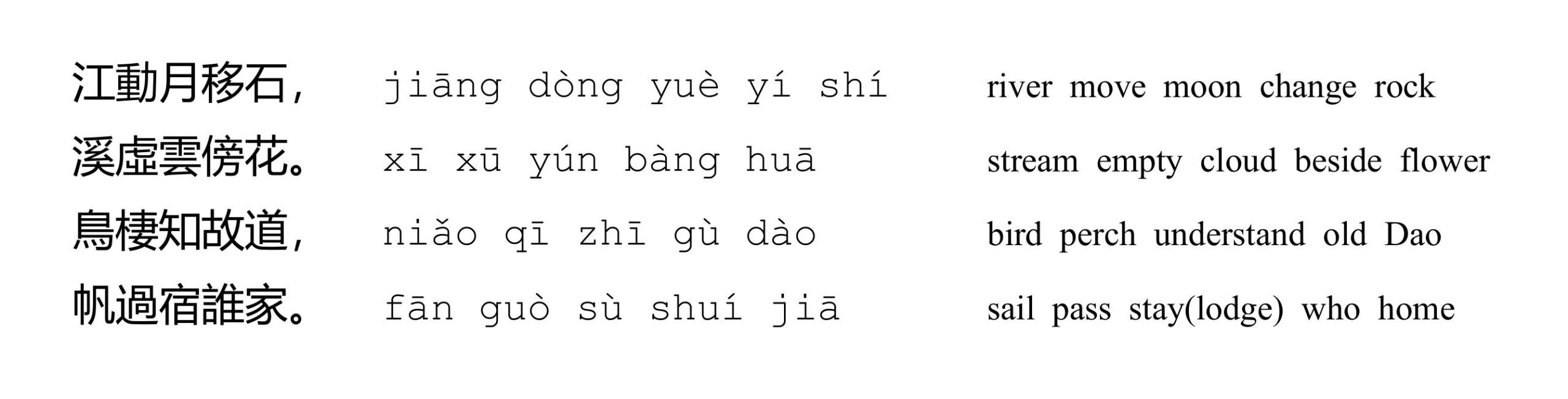

Another quatrain from Chengdu describes a night scene on the river. The following shows the poem in Chinese characters (Owen, 2008, poem 13.61), in pinyin, and in a character-by-character translation (mine):

This is the translation by J. P. Seaton (Seaton & Cryer, 1987):

The River moves, moon travels rock,

Streams unreal, clouds there among the flowers.

The bird perches, knows the ancient Tao

Sails go: They can’t know where.

As the river flows by, the moon’s reflection slowly travels across the rocks near the shore. The water reflects the clouds between the lilies. A bird on a branch understands the nature of the universe. A boat passes, going home we know not where.

The poem conveys a sense of the complexity of the world where reflections and reality intermingle, a desire to understand the meaning of our life, and a fear that time is passing and we do not know where it will take us. All this in twenty characters. Such concision is extremely difficult in English. An attempt:

River and rocks reflect the moon

and clouds amid the lilies

resting birds understand the way

sails pass seeking home somewhere.

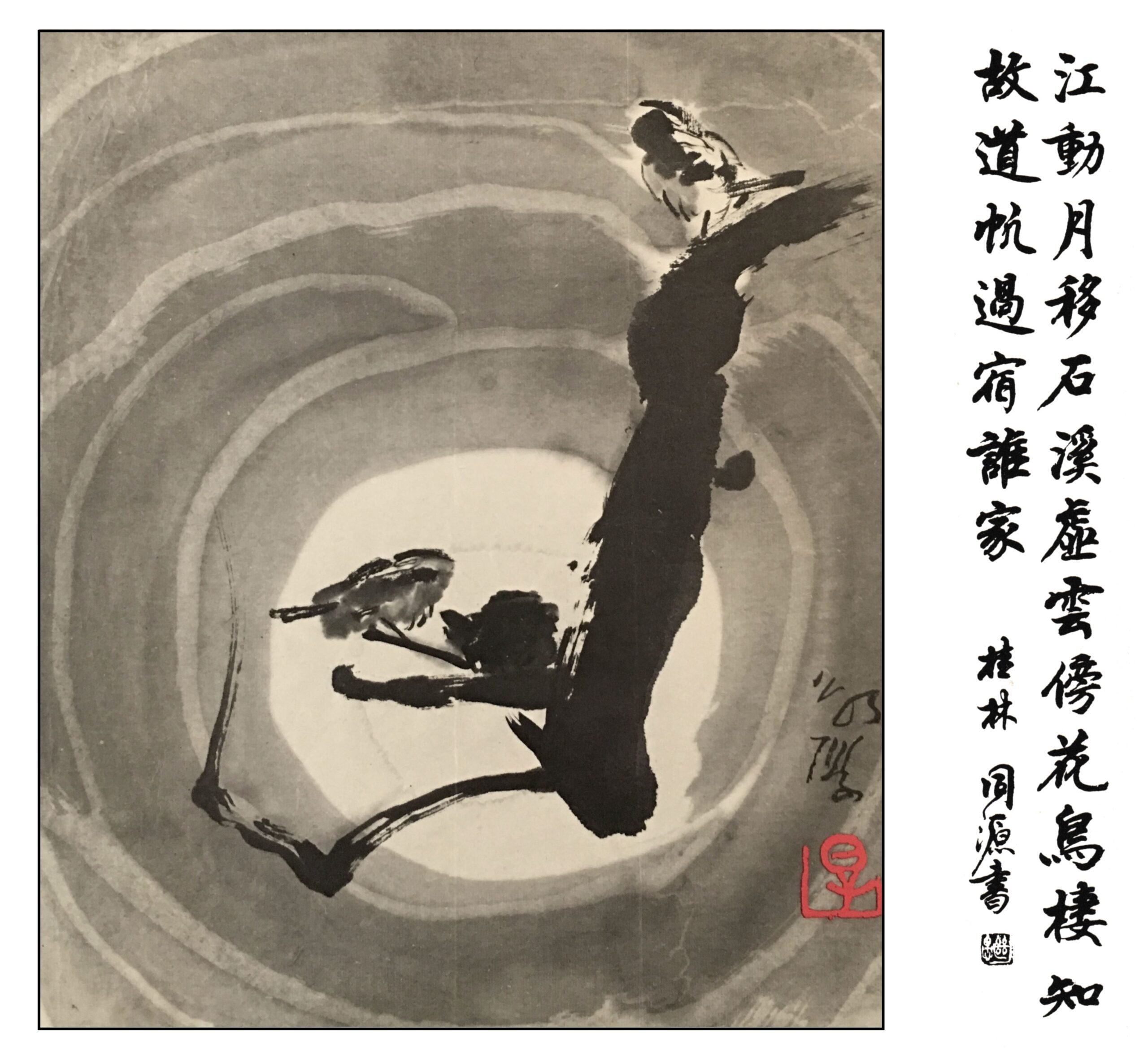

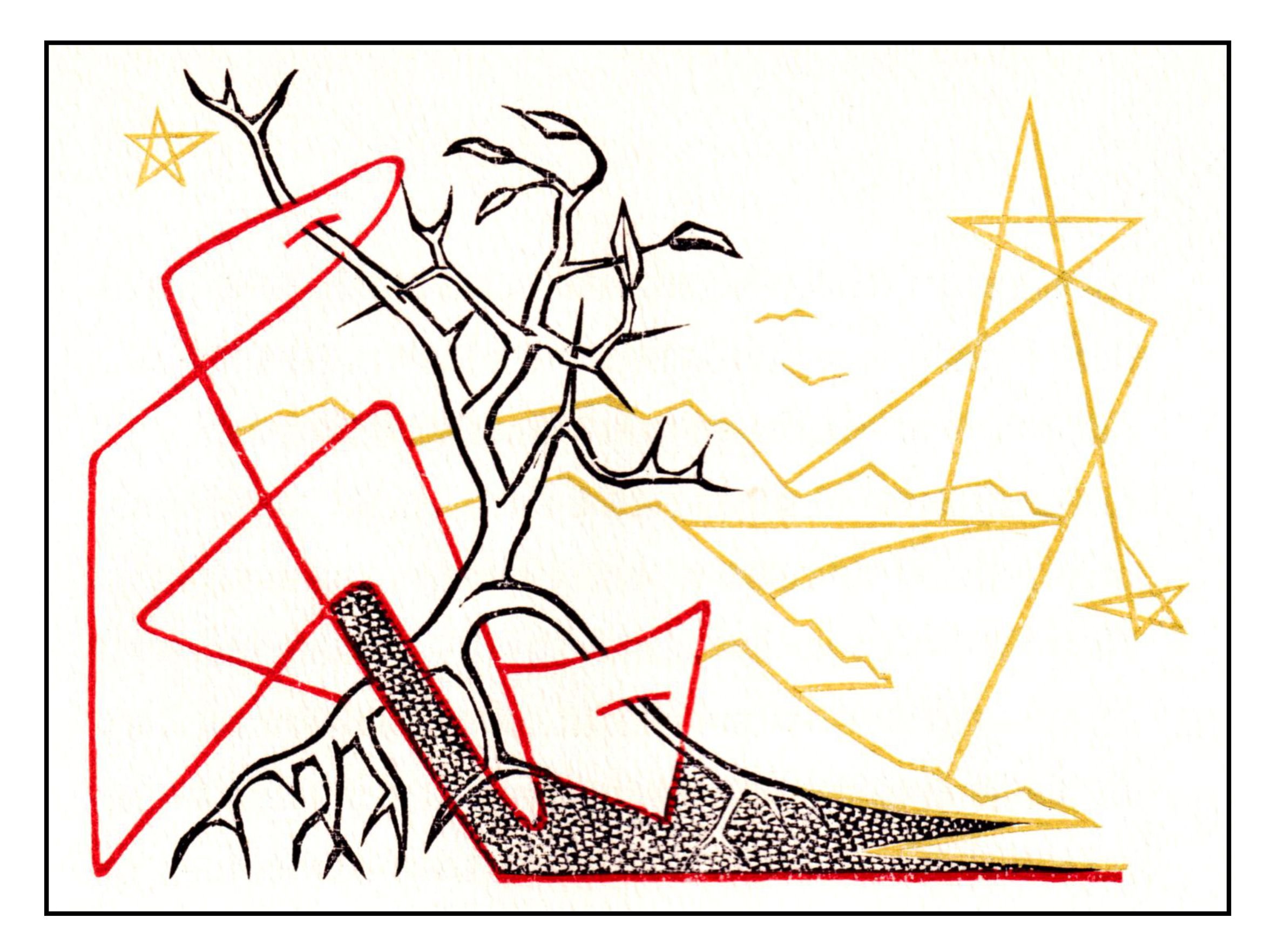

The following shows a painting by Huang Yon-hou to illustrate the poem. This was used as the frontispiece (and cover) of the book Bright Moon, Perching Bird (Seaton & Cryer, 1987). On the right is calligraphy of the poem by Mo Ji-yu.

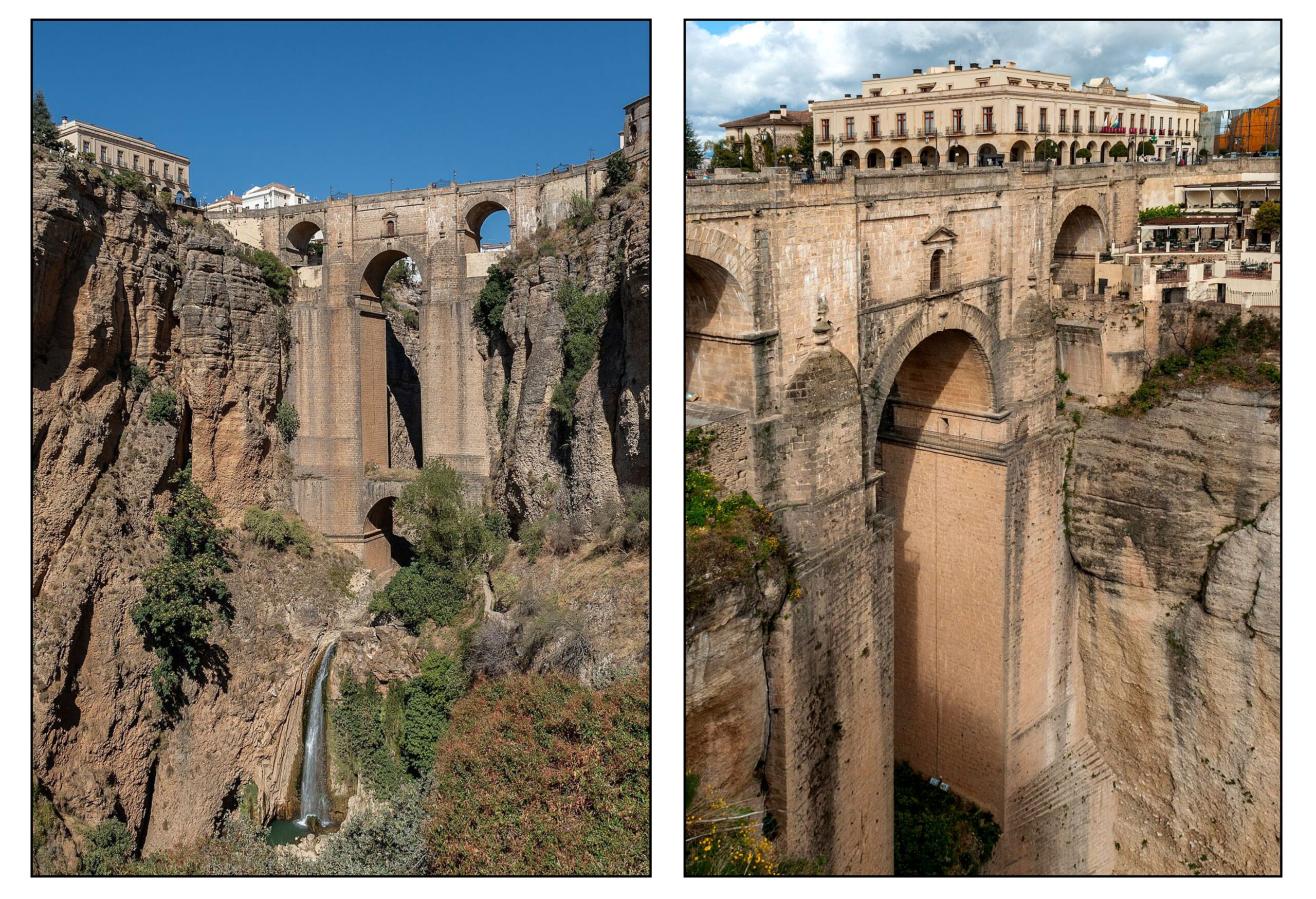

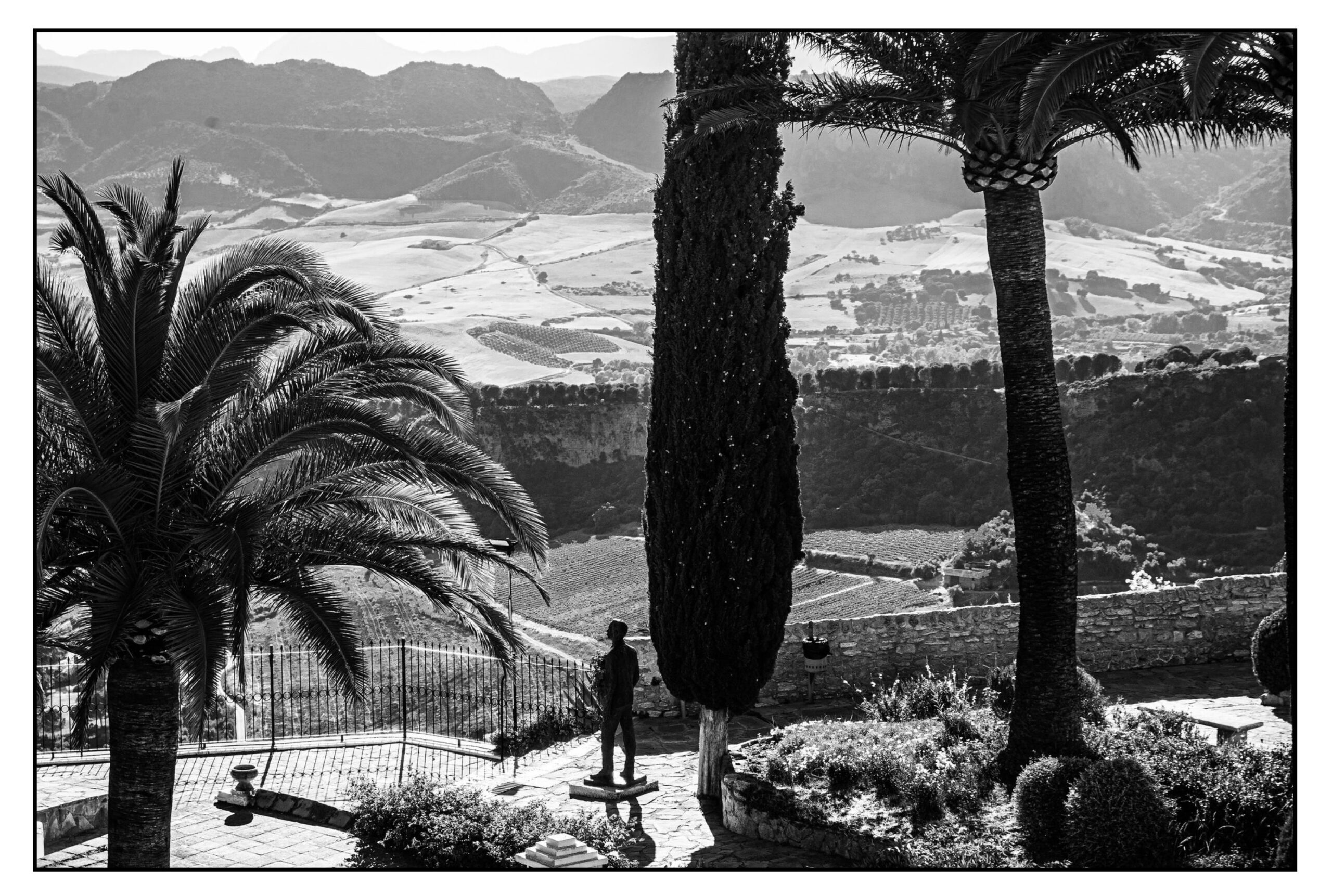

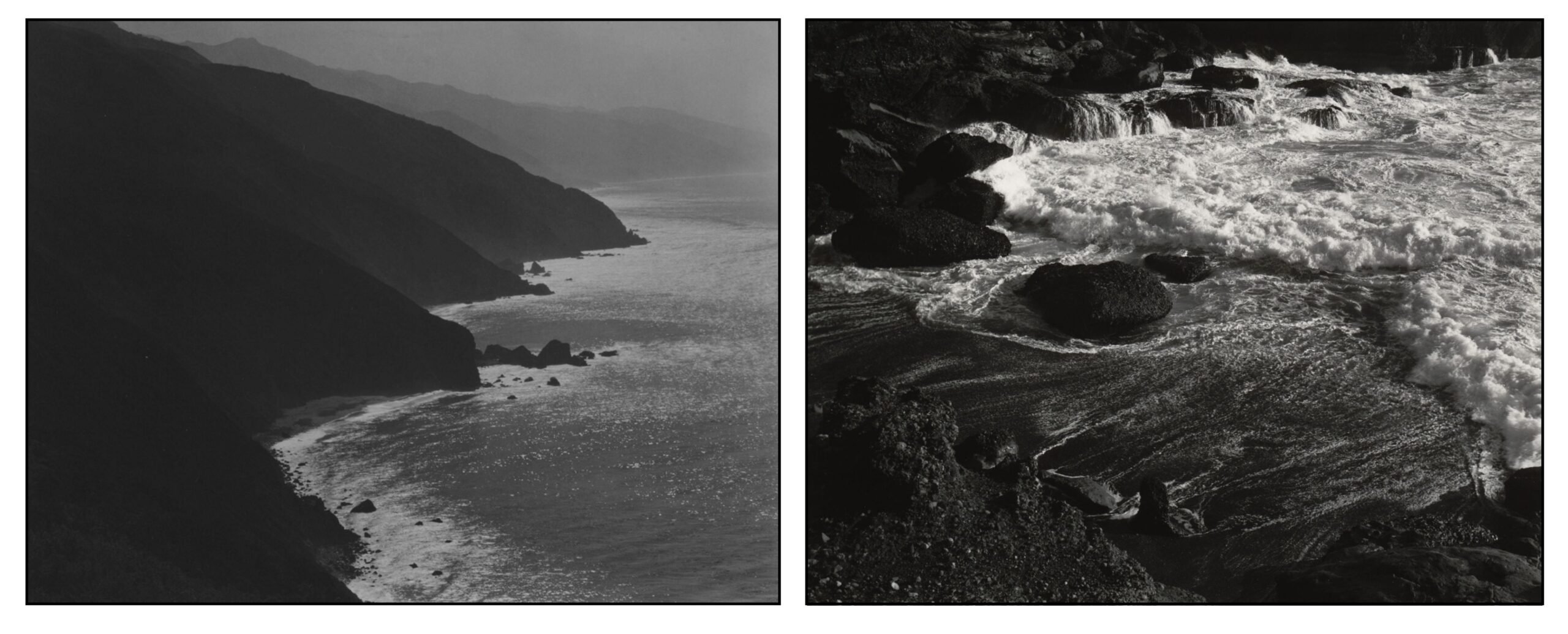

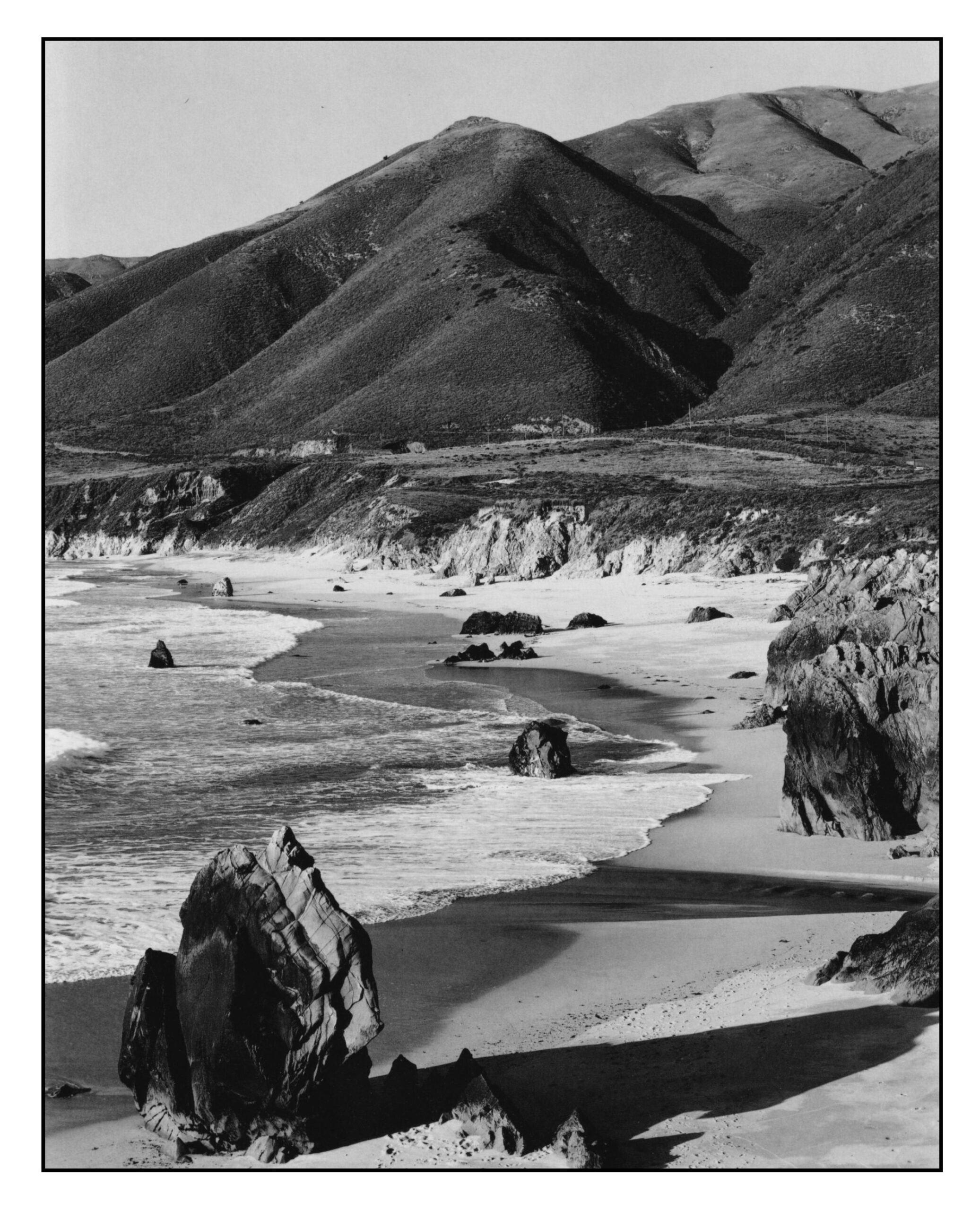

Above the Gorges

In 765 CE Du Fu and his family left Chengdu and travelled eastward on the Yangtze River. The region of Luoyang had been recently recovered by imperial forces and Du Fu was perhaps trying to return home (Hung, 1952). He stayed for a while in Kuizhou (present day Baidicheng) at the beginning of the Three Gorges (Qutang, Wu and Xiing).

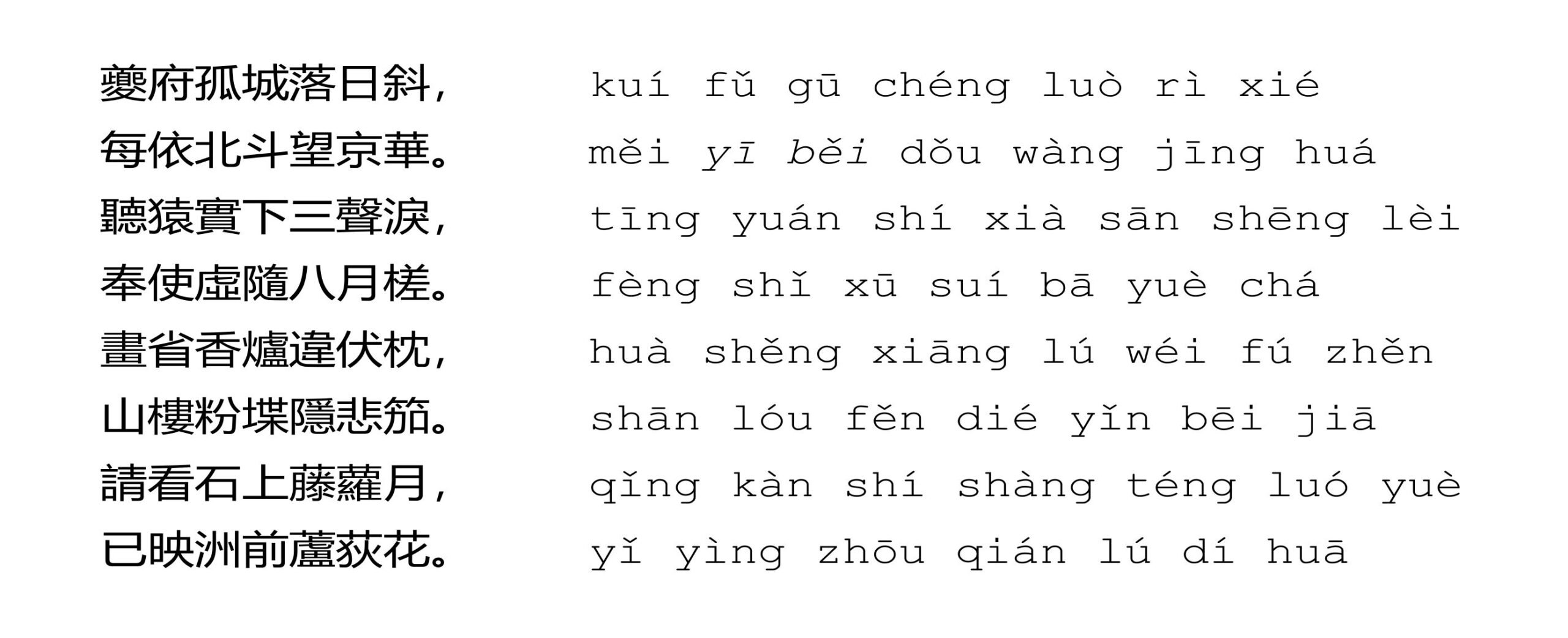

While there Du Fu wrote a series of meditations called Autumn Thoughts (or more literally Stirred by Autumn). This is the second of these poems in Chinese characters and in pinyin:

A character-by-character translation (Alexander, 2008) is:

Kui prefecture lonely wall set sun slant

Every rely north dipper gaze capital city

Hear ape real fall three sound tear

Sent mission vain follow eight month raft

Picture ministry incense stove apart hidden pillow

Mountain tower white battlements hide sad reed-whistle

Ask look stone on [Chinese wisteria] moon

Already reflect islet before rushes reeds flowers

The following is Stephen Owen’s translation (Owen, 2008 poem 17.27):

On Kuizhou’s lonely walls setting sunlight slants,

then always I trust the North Dipper to lead my gaze to the capital.

Listening to gibbons I really shed tears at their third cry,

accepting my mission I pointlessly follow the eighth-month raft.

The censer in the ministry with portraits eludes the pillow where I lie,

ill towers’ white-plastered battlements hide the sad reed pipes.

Just look there at the moon, in wisteria on the rock,

it has already cast its light by sandbars on flowers of the reeds.

The poem is striking in the difference between the first three couplets and the last. At the beginning of the poem Du Fu is feeling regret that he is not in Chang’an which is located due north of Kuizhou (in the direction of the Big Dipper which points to the North Star). Owen notes that “There was an old rhyme that a traveler in the gorges would shed tears when the gibbons cried out three times.” The eighth month raft may refer to another old story about a vessel that came every eight months and took a man up to the Milky Way. Owen commented on the third couplet that “The “muralled ministry” is where were located the commemorative portraits of officers, civil and military, who had done exceptional service to the dynasty.” Incense was burned when petitions were presented. The final couplet disregards all the preceding nostalgia and simply appreciates the beauty of the moment.

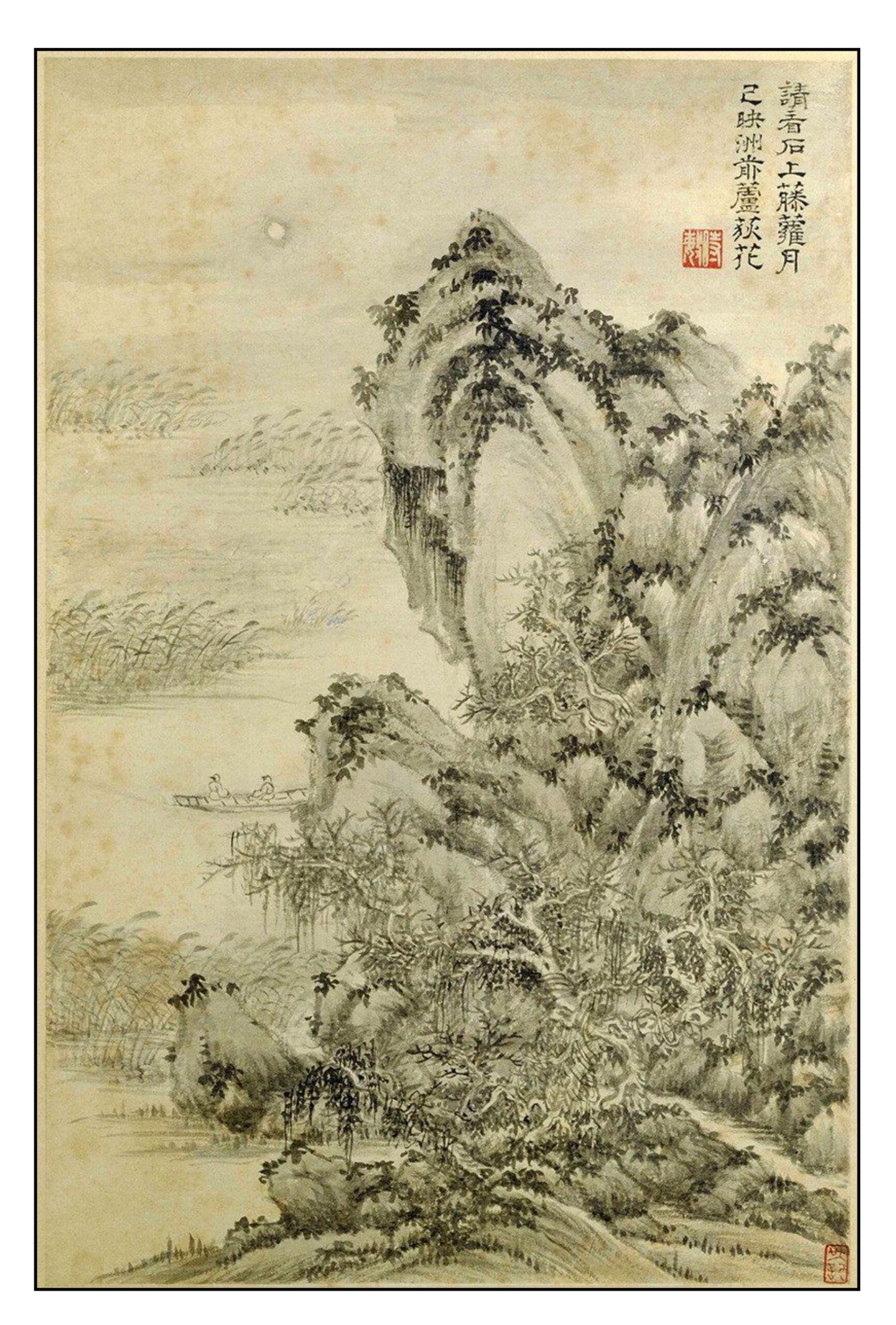

The Ming painter Wang Shimin illustrated this final couplet in one of the leaves from his album Du Fu’s Poetic Thoughts.

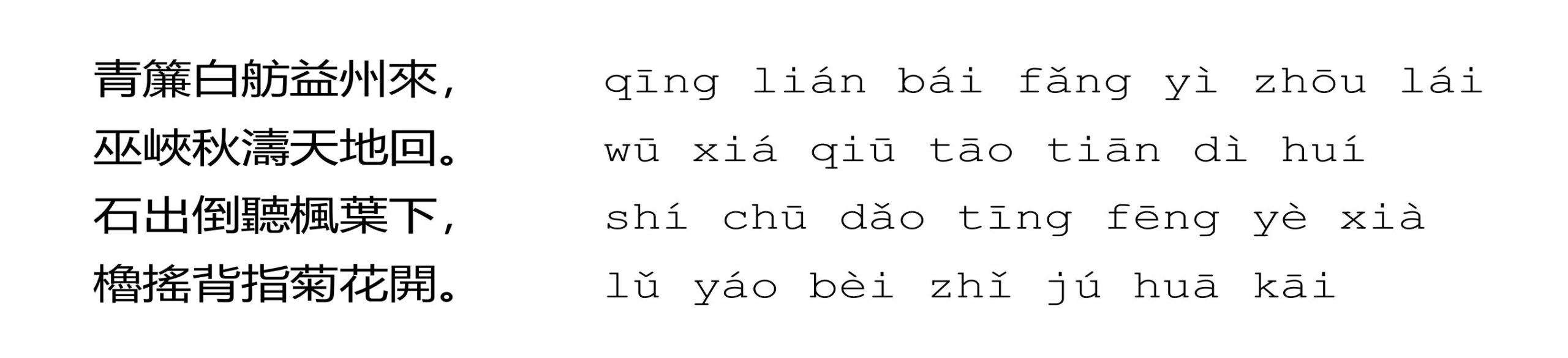

Later in Kuizhou, Du Fu entertained a librarian named Li who was returning north to take up an appointment in Chang’an. The following is the beginning of a poem (Owen, 2008, poem 19.34) describing Li’s departure in Chinese characters and in pinyin:

A character-by-character translation is:

blue/green curtain white boat/raft Yizhou arrive

Wu gorge autumn waves heaven/sky earth/ground turn (around)

stone/rock leave/exit fall listen maple leaf down

scull/oar swing carry point chrysanthemum flower open/blume

The following is Stephen Owen’s translation:

When the white barge with green curtains came from Yizhou,

with autumn billows in the Wu Gorges, heaven and earth were turning.

Where rocks came out, from below you listened to the leaves of maples falling,

as the sweep moved back and forth you pointed behind to chrysanthemums in bloom.

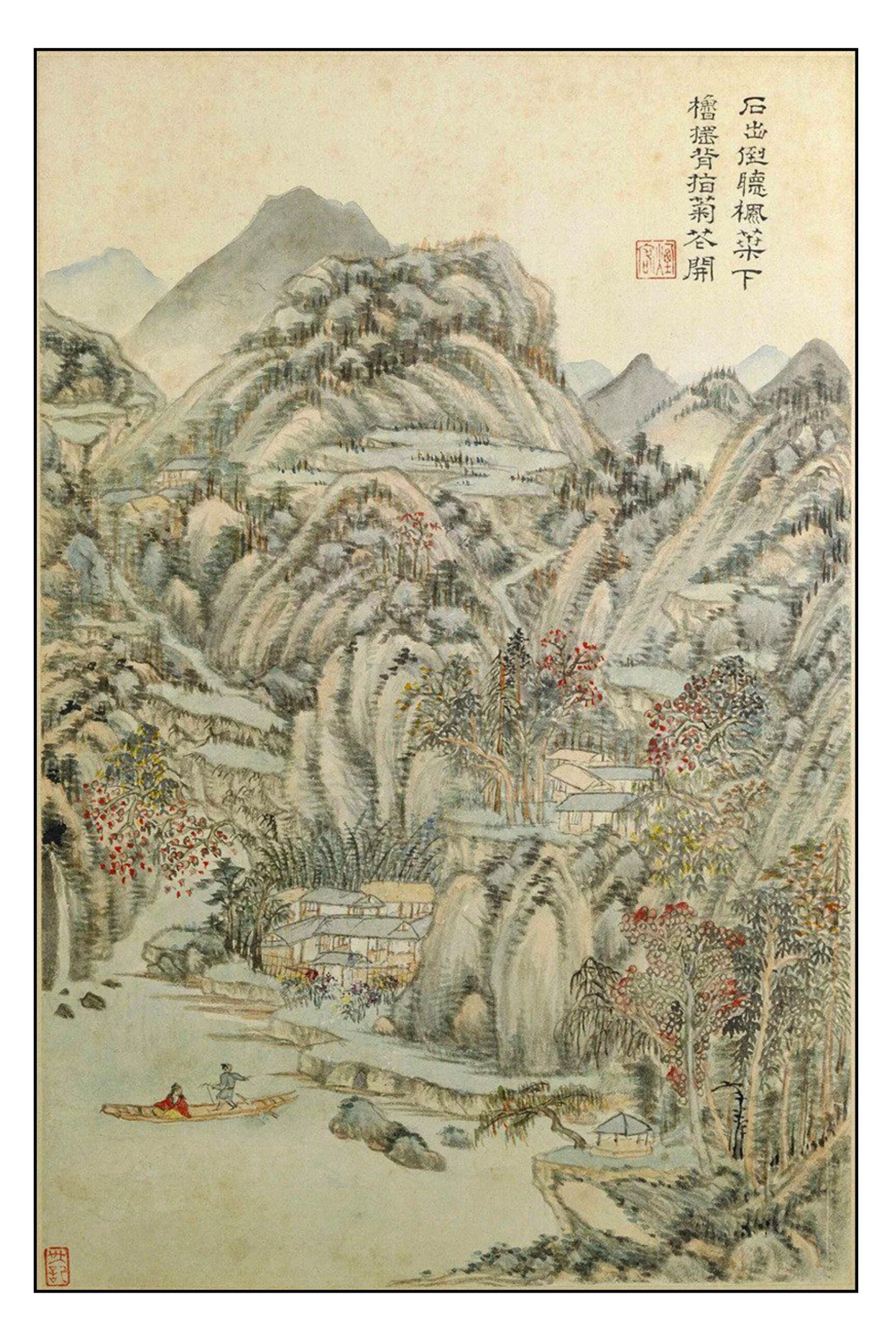

The Ming painter Wang Shimin illustrated the second couplet in one of the leaves from his album Du Fu’s Poetic Thoughts. The painting shows the bright red leaves of the maples. In front of the riverside house one can see the multicolored chrysanthemums that Li is pointing to. Harmony exists between the wild and the cultivated.

On the River

After his sojourn in Kuizhou, Du Fu and his family continued their journey down the Yangtze River. However, the poet was ill and was unable to make it beyond Tanzhou (now Changsha) where he died in 770 CE. No one knows where he is buried. In the 1960’s radical students dug up a grave purported to be his to “eliminate the remaining poison of feudalism,” but found the grave empty.

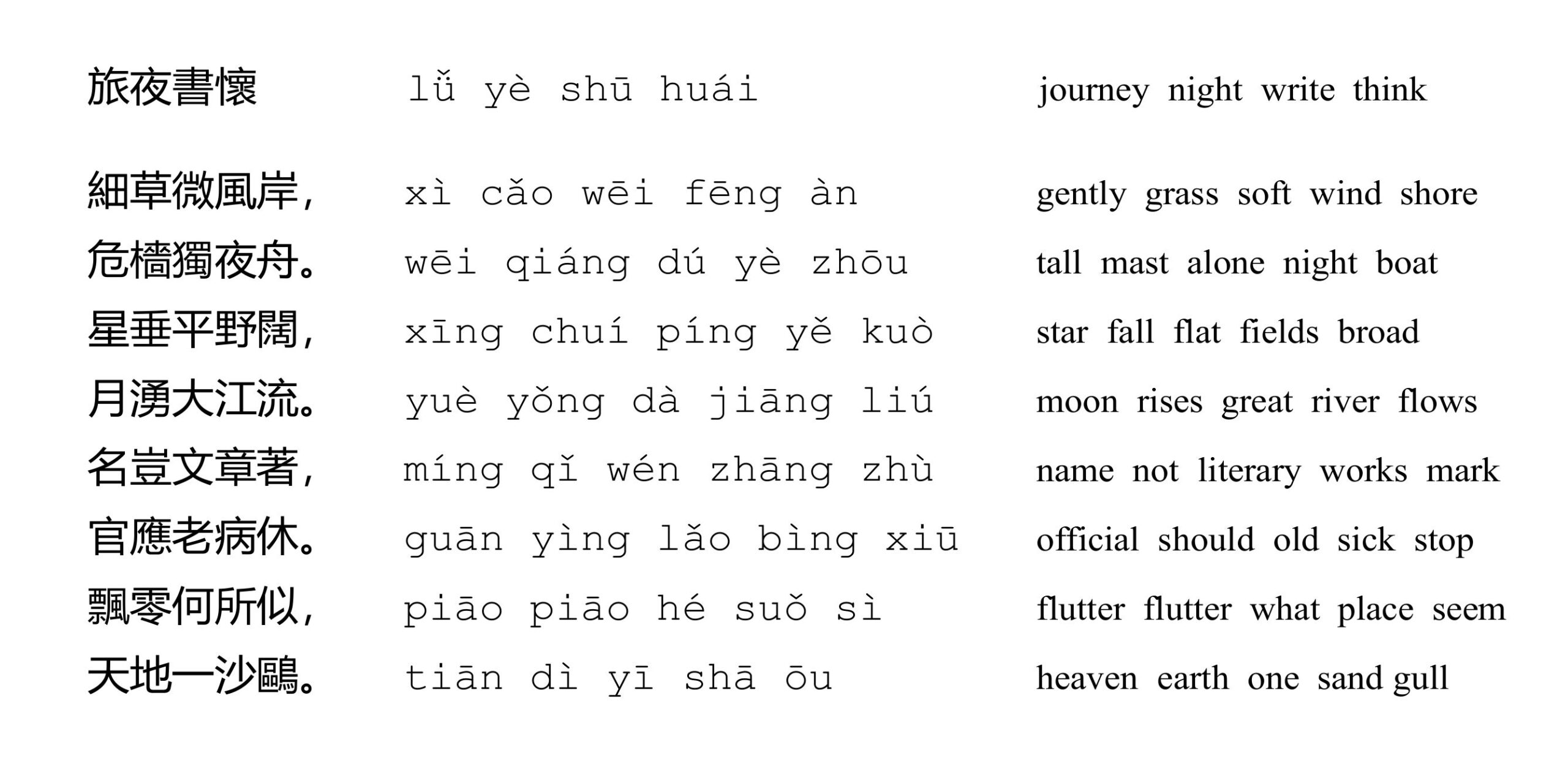

One of Du Fu’s last poems was Night Thoughts While Travelling. The following is the poem in Chinese characters (Owen, 2008, poem 14.63) and in pinyin (Alexander, 2008):

The following is a reading of the poem from Librivox:

Holyoak (2015) provides a rhymed translation:

The fine grass

by the riverbank stirs in the breeze;

the tall mast

in the night is a lonely sliver.

Stars hang

all across the vast plain;

the moon bobs

in the flow of the great river.

My poetry

has not made a name for me;

now age and sickness

have cost me the post I was given.

Drifting, drifting,

what do I resemble?

A lone gull

lost between earth and heaven.

Kenneth Rexroth (1956) translates the poem in free verse:

Night Thoughts While Travelling

A light breeze rustles the reeds

Along the river banks. The

Mast of my lonely boat soars

Into the night. Stars blossom

Over the vast desert of

Waters. Moonlight flows on the

Surging river. My poems have

Made me famous but I grow

Old, ill and tired, blown hither

And yon; I am like a gull

Lost between heaven and earth.

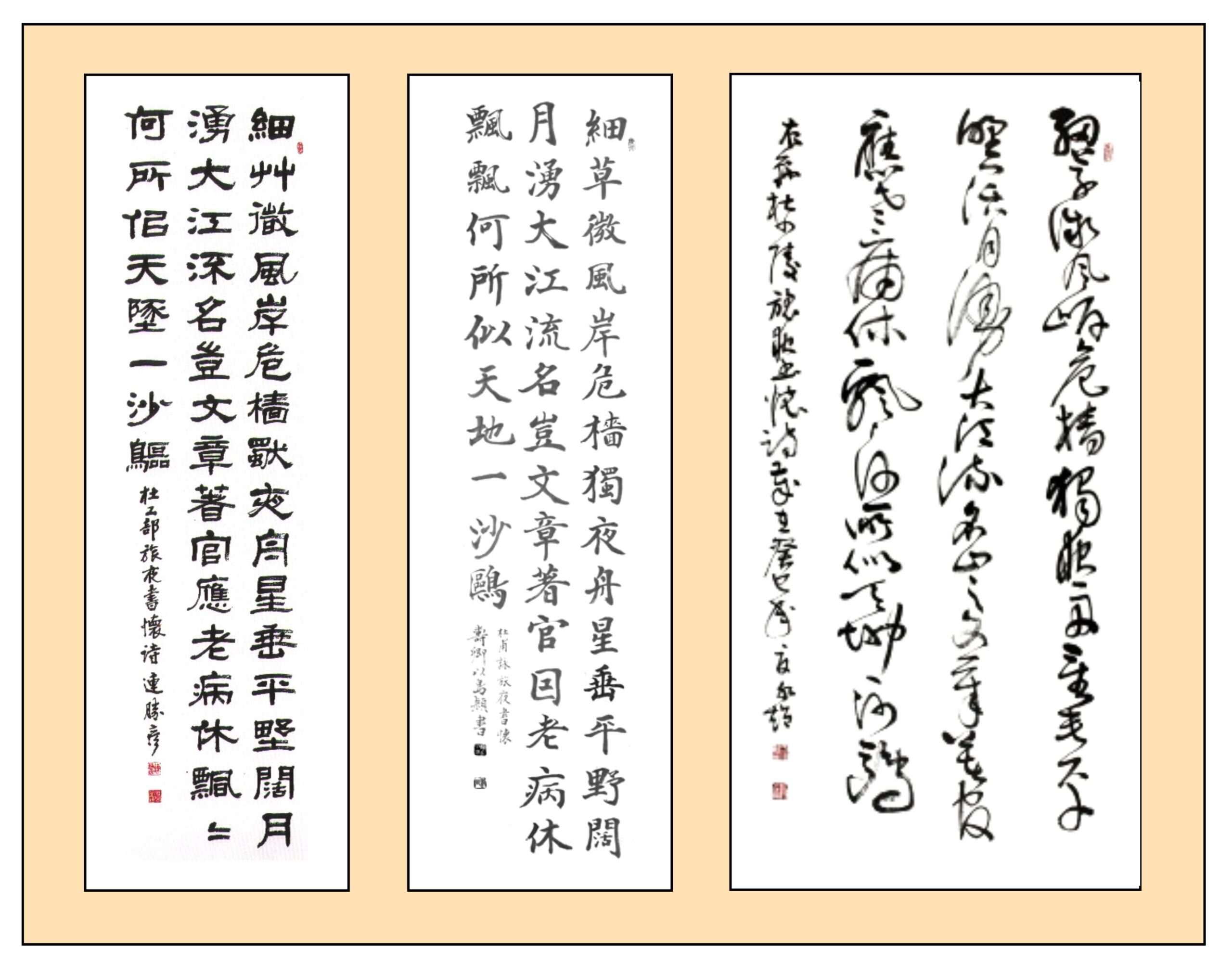

The following shows the poem in calligraphy with three styles. On the left the poem is written in clerical script, in the center in regular script and on the right is unrestrained cursive script. All examples were taken from Chinese sites selling calligraphy.

Changing Times

During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) the role of literature, and poetry in particular, in society changed dramatically (Owen, 2011):

In the 650s, literature was centered almost entirely in the imperial court; by the end of the era literature had become the possession of an educated elite, who might serve in government, but whose cultural life was primarily outside the court.

During Du Fu’s lifetime, poetry became no longer a part of the ancient traditions; rather it began to be concerned with the present and with the personal. Lucas Bender (2021) describes the traditional role of poetry in a society following the precepts of Confucianism:

Most people … would be incapable on their own of adequately conceptualizing the world or perfectly responding to its contingency, and therefore needed to rely on the models left by sages and worthies. Many of these models were embodied in texts, including literary texts, which could thus offer an arena for ethical activity. Poetry, for example, was understood to offer models of cognition, feeling, and commitment that would ineluctably shape readers’ understanding of and responses to their own circumstances. One way of being a good person, therefore, involved reading good poetry and writing more of it, thereby propagating the normative models of the tradition in one’s own time and transmitting them to the future. (p 317)

Du Fu found himself bewildered by the state of the world. He sought to convey this confusion rather than explain it:

Du Fu doubts the possibility of indefinitely applicable moral categories. The conceptual tools by which we make moral judgments, he suggests, are always inherited from a past that can – and, in a world as various and changeable as ours has proven to be, often will – diverge from the exigencies of the present. As a result, not only are our values unlikely to be either universal or timeless; more important, if we pay careful attention to the details of our experience, they are unlikely to work unproblematically even here and now. (Bender, 2021, p 319)

The complexity of Du Fu’s poetry – the difficulty in understanding some of his juxtapositions – becomes a challenge. The past provides no help in the interpretation. We must figure out for themselves what relates the mountain, the clouds and the poet’s breathing in the first poem we considered. And in the last poem we must try to locate for ourselves the place of the gull between heaven and earth.

References

Alexander, M. (2008). A little book of Du Fu. Mark Alexander. (Much of the material in the book is available on Chinese Poems website).

Bender, L. R. (2021). Du Fu transforms: tradition and ethics amid societal collapse. Harvard University Asia Center.

Chan, J. W. (2018). Du Fu: the poet as historian. In Zong-Qi Cai. (Ed.) How to read Chinese poetry in context: poetic culture from antiquity through the Tang. (pp 236-247). Columbia University Press.

Chou, E. S. (1995). Reconsidering Tu Fu: literary greatness and cultural context. Cambridge University Press.

Collet, H., & Cheng, W. (2014). Tu Fu: Dieux et diables pleurant, poèmes. Moundarren.

Cooper, A. R. V. (1973). Li Po and Tu Fu. Penguin Books.

Egan, R. (2020). Ming-Qing paintings inscribed with Du Fu’s poetic lines. In Xiaofei Tian (Ed.). Reading Du Fu: nine views. (pp 129-142). Hong Kong University Press

Hawkes, D. (1967 revised and reprinted, 2016). A little primer of Tu Fu. New York Review of Books.

Hinton, D. (1989, expanded and revised 2020a). The selected poems of Tu Fu. New Directions.

Hinton, D. (2019). Awakened cosmos: the mind of classical Chinese poetry. Shambhala.

Hinton, D. (2020b). China root: Taoism, Ch’an, and original Zen. Shambhala

Holyoak, K. (2015). Facing the moon: poems of Li Bai and Du Fu. Oyster River Press.

Hsieh, D. (1994). Du Fu’s “Gazing at the Mountain.” Chinese Literature, Essays, Articles, Reviews, 16, 1–18.

Hung, W. (1952, reprinted 2014). Tu Fu: China’s Greatest Poet. Harvard University Press

Owen, S. (1981). Tu Fu. In S. Owen, The Great Age of Chinese Poetry: The High T’ang. (pp 183-224). Yale University.

Owen, S. (2010). The cultural Tang (650–1020). In Chang, K. S., & Owen, S. (Eds). The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature (Vol. 1, pp. 286–380). Cambridge University Press.

Owen, S., (edited by P. W. Kroll & D. X. Warner, 2016). The poetry of Du Fu. (6 volumes). De Gruyter. (Available to download in pdf format.)

Rexroth, K. (1956). One hundred poems from the Chinese. New Directions.

Rouzer, P. (2020). Refuges and refugees: how Du Fu writes Buddhism. In Xiaofei Tian (Ed.). Reading Du Fu: nine views. (pp. 75-92). Hong Kong University Press.

Seaton, J. P., & Cryer, J. (with calligraphy by Mo Ji-yu, and painting by Huang Yon-hou, 1987). Bright moon, perching bird: poems of Li Po and Tu Fu. Wesleyan University Press.

Seth, V. (1997). Three Chinese poets: translations of poems by Wang Wei, Li Bai and Du Fu. Phoenis.

Sullivan, M. (1974). The three perfections: Chinese painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Thames and Hudson.

Xiaofei Tian (Ed.). (2020). Reading Du Fu: nine views. Hong Kong University Press.

Zhang, Y. (2018). On 10 Chan-Buddhism images in the poetry of Du Fu. Studies in Chinese Religions, 4(3), 318–340.

Wai-lim Yip. (1997). Chinese Poetry, Duke University Press.

Watson, B. (2002). The selected poems of Du Fu. Columbia University Press.

Wong, S. S. (1970) The quatrains (Chüeh-Chü 絕句) of Tu Fu. Monumenta Serica, 29, 142-162

Yang, M. V. (2016). Man and nature: a study of Du Fu’s poetry. Monumenta Serica, 50, 315-336.

Young, D. (2008). Du Fu: a life in poetry. Alfred A. Knopf.

Zong-Qi Cai (2008). How to read Chinese poetry: a guided anthology. Columbia University Press. (audio files are available at website).