The Cathars

From the 12th to 15th Centuries groups of people called the Cathars lived quietly in various regions of Western Europe – Northern Italy, the Rhineland and, most especially, Southern France. They followed the moral teachings of Jesus, forsaking worldly goods and loving one another, but they did not believe in the basic theology of Christianity. They considered that the world was evil, that human beings were spirits imprisoned in the flesh, and that the soul could only be set free at death if one had lived a life of purity. The Catholic Church considered these beliefs heretical, and in 1208 Pope Innocent III called for a crusade to eradicate the heresy. Named after the inhabitants of the city of Albi which had a flourishing Cathar population, the Albigensian Crusade lasted from 1209 until 1229. After years of terrible violence and cruelty, most of those who professed Cathar beliefs were dead. All that now remains of these peaceful people are the ruins of the hilltop castles in which they sought refuge.

Heresy and Dissent in the Middle Ages

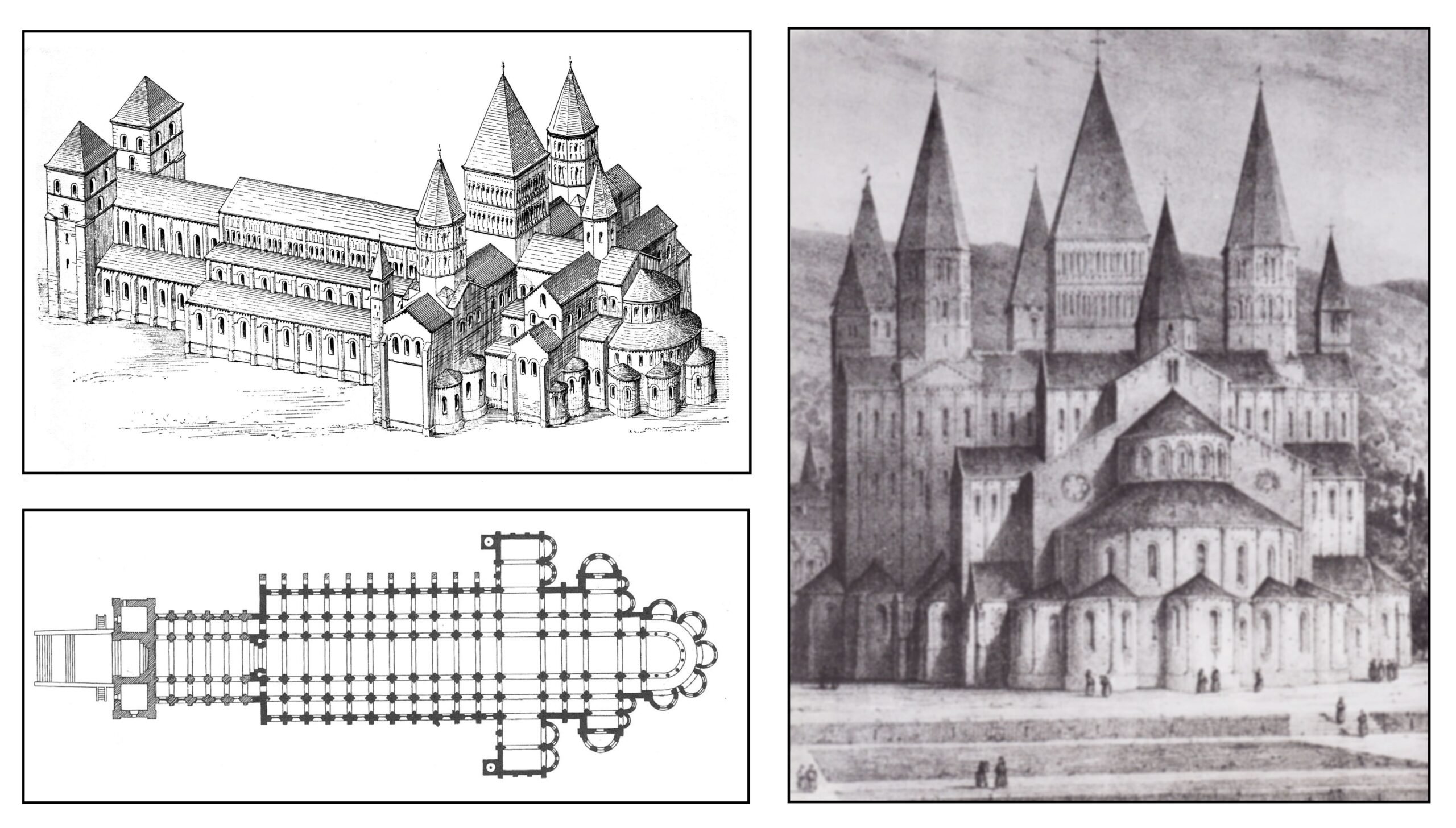

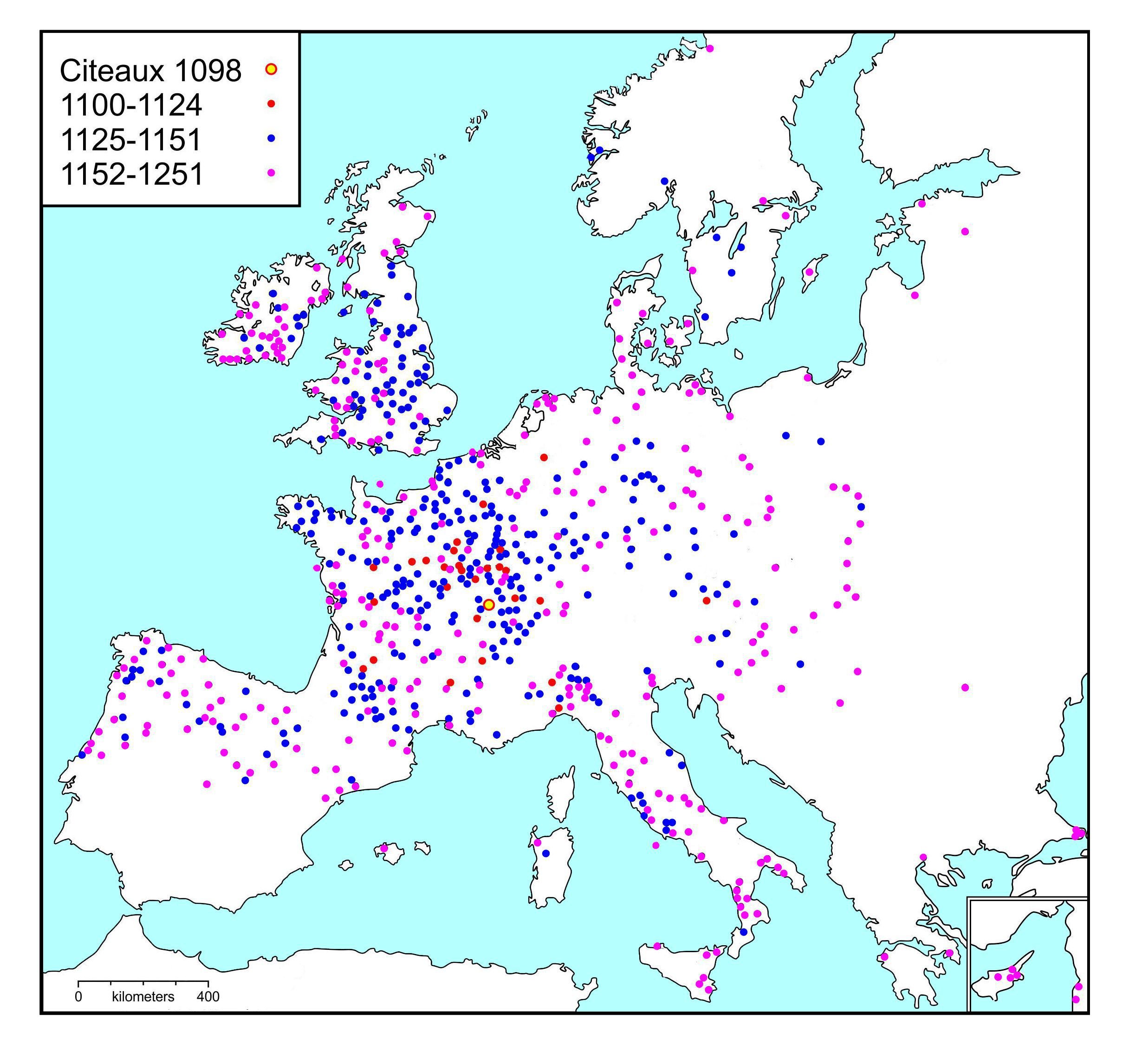

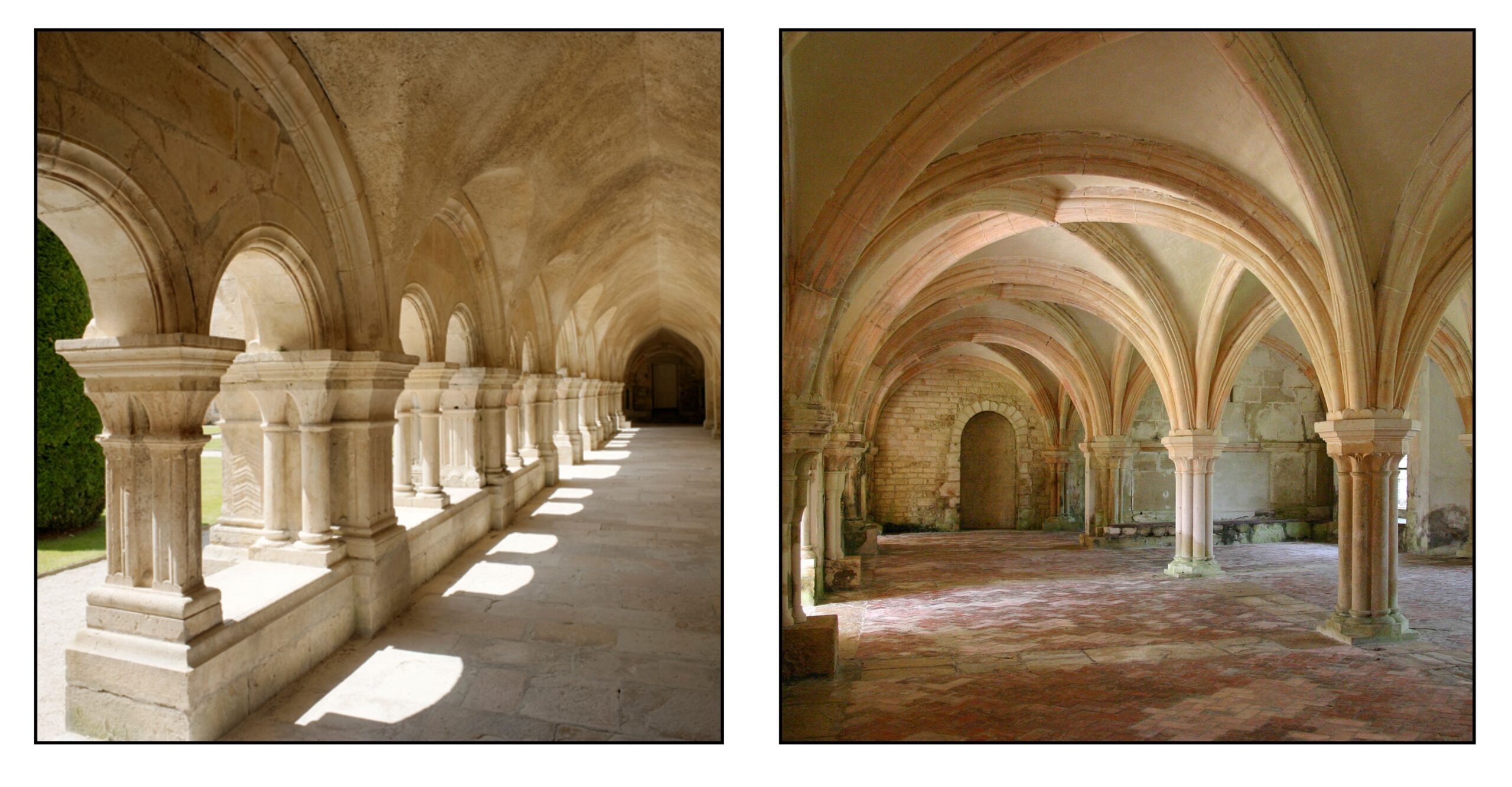

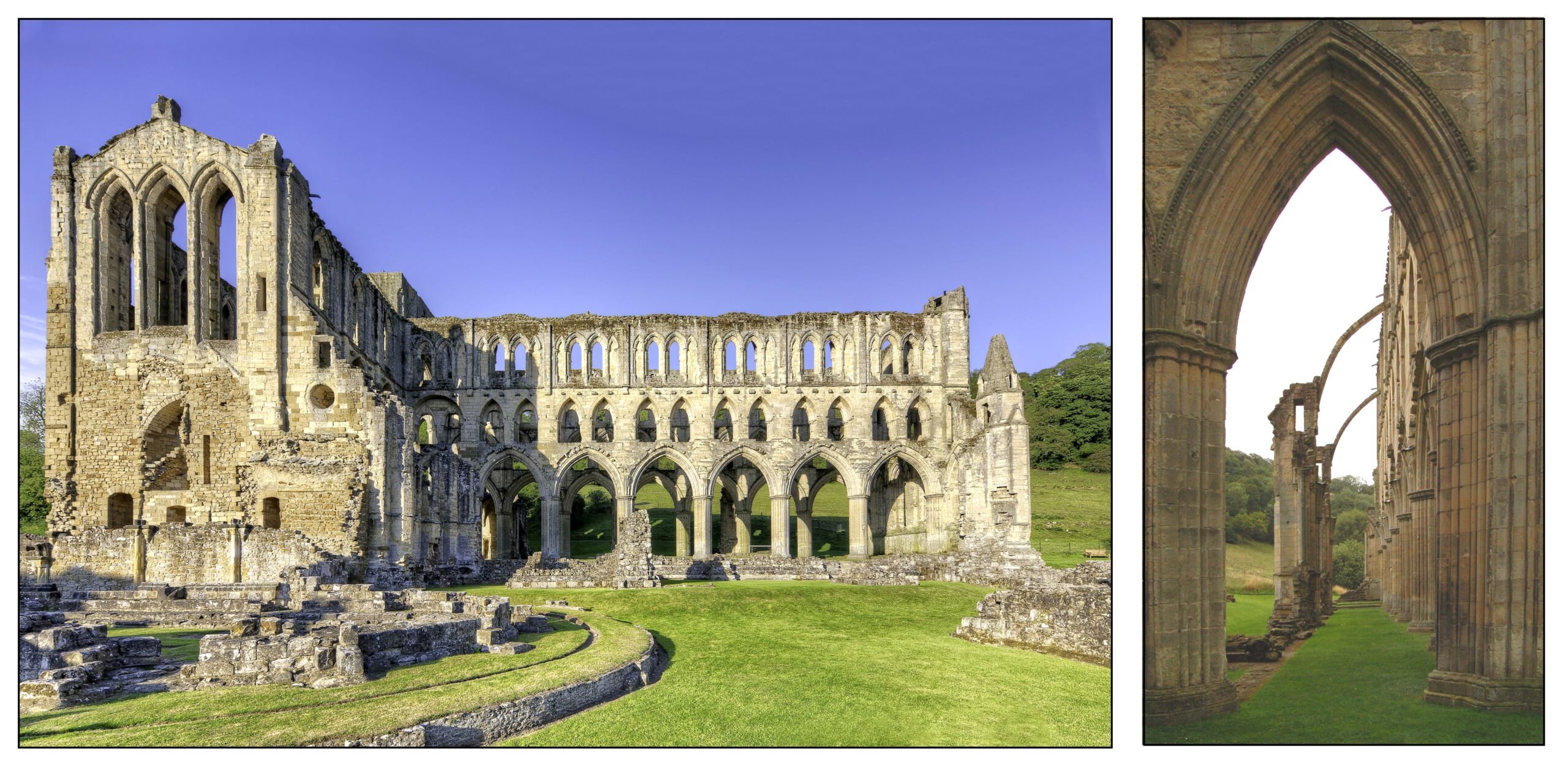

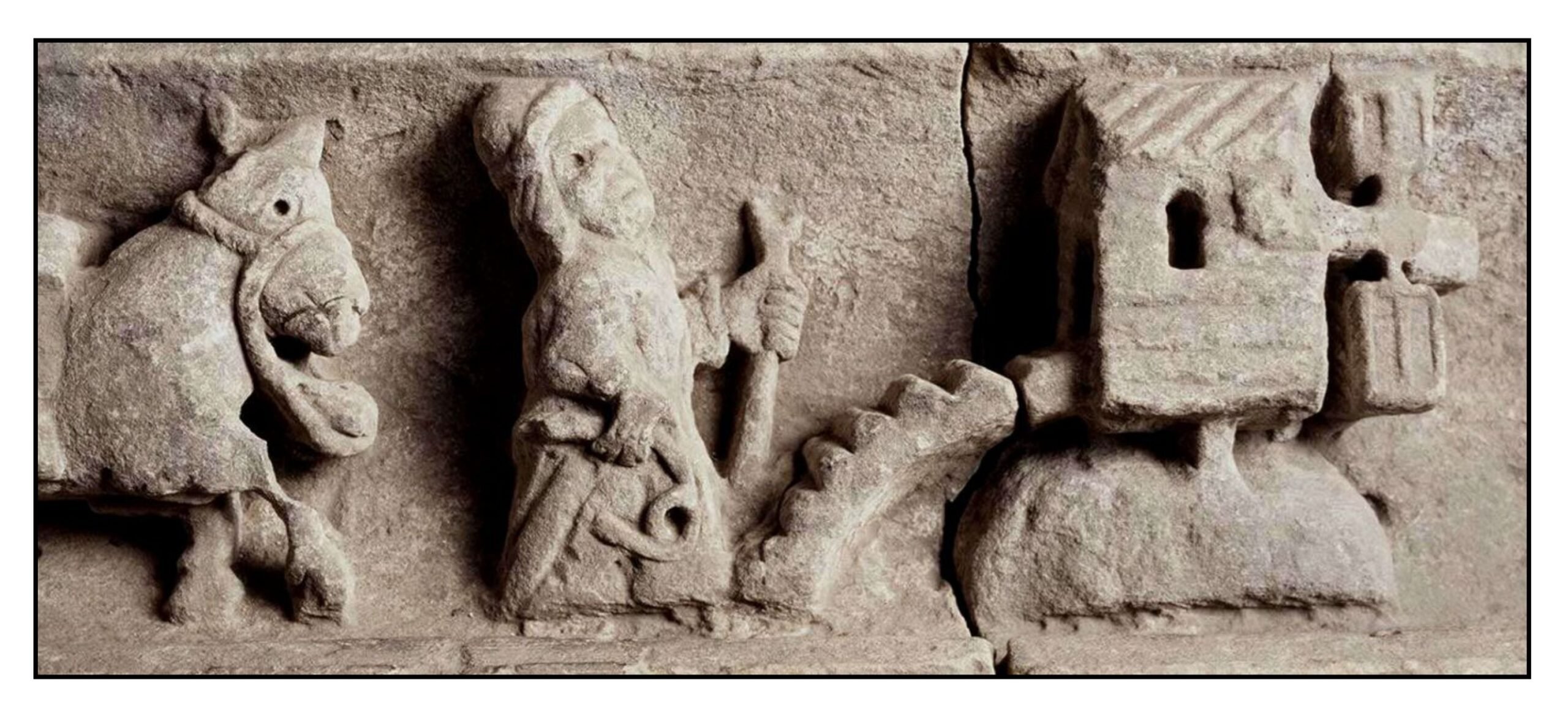

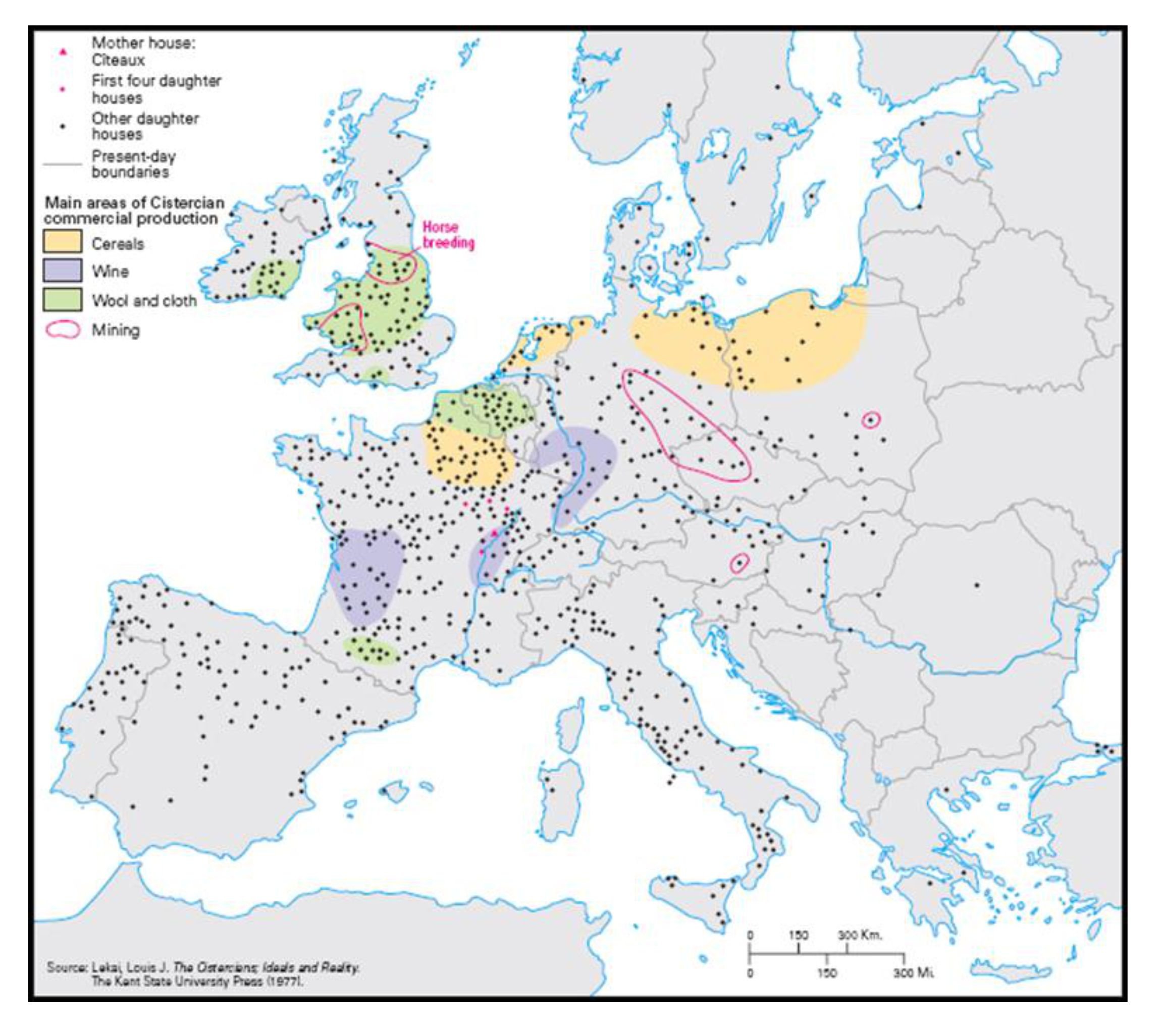

The increasing secular power and the ostentatious luxury the Catholic Church were far from the life of poverty and compassion taught by Jesus. This contrast triggered dissent in various forms (Moore, 1985). In 1098 a group of monks left the Benedictine monastery and founded the order of the Cistercians. In 1135, Henry of Lausanne, who had taught throughout the South of France that the individual believer was more important than the church, was condemned as heretical. In 1143 and again in 1163, small groups of heretics who denied the authority of the Catholic Church were burned at the stake in Cologne. In 1173 in Lyons, a merchant named Valdes (also known as Waldo) began preaching a life of apostolic poverty as the way to salvation. His followers, who became known as the Waldensians, were initially tolerated but later considered heretics.

The monk Eberwin of Steinfeld Abbey near Cologne wrote to Bernard of Clairvaux about the heretics of 1143. He was astounded by their fortitude in accepting death rather than disavowing their beliefs, and he tried to understand them:

This is their heresy: They say that the Church exists among them only, since they alone follow closely in the footsteps of Christ, and remain the true followers of the manner of life observed by the Apostles, inasmuch as they possess neither houses, nor fields, nor property of any kind. They declare that, as Christ did not possess any of these Himself, so He did not permit His disciples to possess them. ‘But you,’ they say to us, ‘add house to house, and field to field, and seek the things of this world. So completely is this the case, that even those among you who are considered most perfect, such as the monks and regular canons, possess these things, if not as their private property, yet as belonging to their community.’ Of themselves they say: ‘We are the poor of Christ; we have no settled dwelling-place; we flee from city to city, as sheep in the midst of wolves; we endure persecution, as did the Apostles and the martyrs: yet we lead a holy and austere life in fasting and abstinence, continuing day and night in labours and prayers, and seeking from these only what is necessary to sustain life. We endure all this,’ they say,‘because we are not of this world.’ (Mabillon & Eales, 1896, p 390).

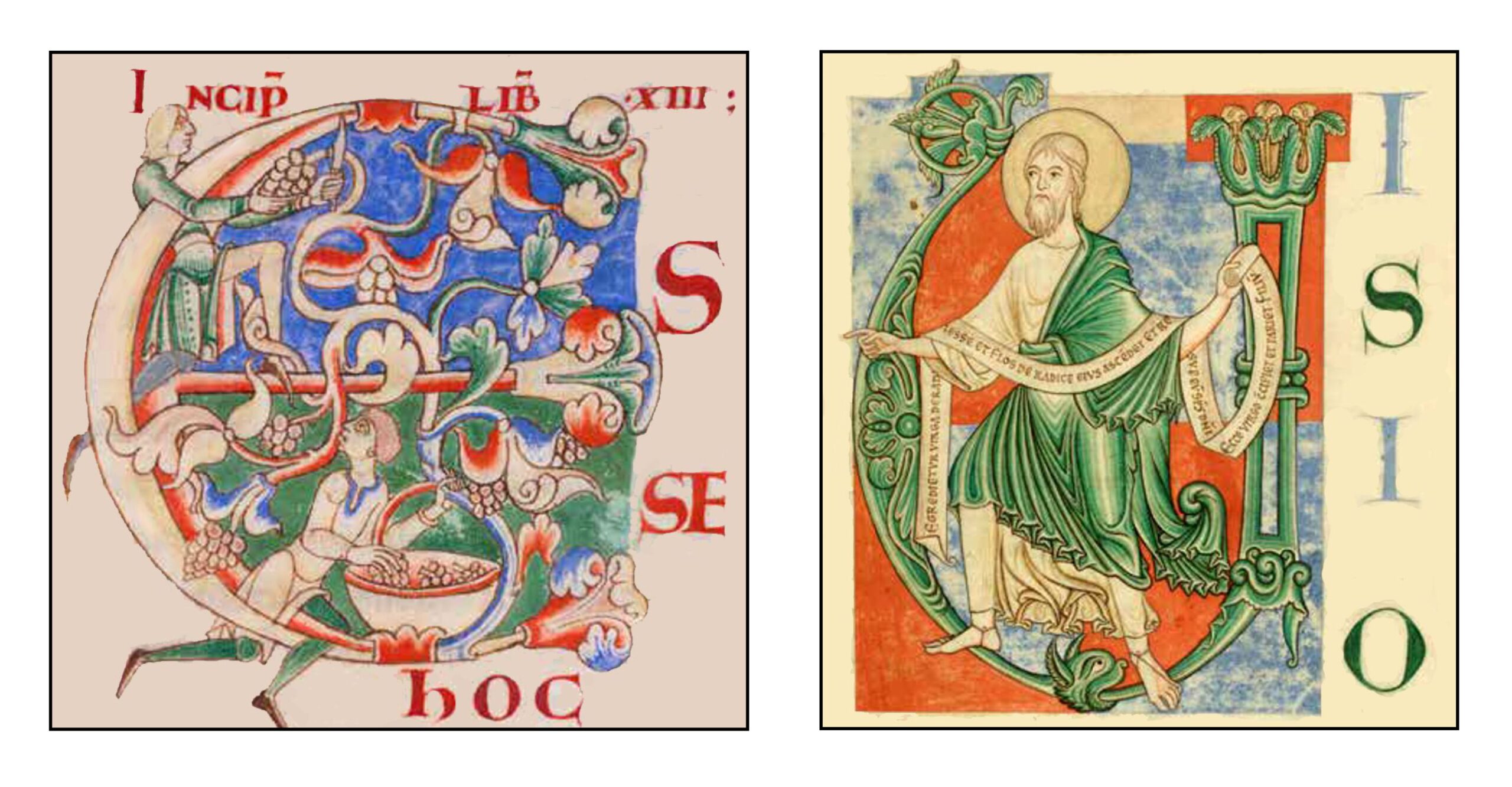

Bernard considered the danger of these apparently innocent heretics, and in his series of sermons on the Song of Songs (also known as the Song of Solomon), he expounded upon the verse

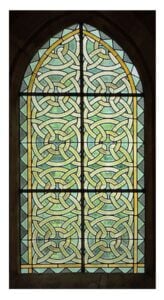

Take us the foxes, the little foxes, that spoil the vines: for our vines have tender grapes. (Song of Solomon 2:15)

He proposed that the vines are those of the Church and the little foxes are the heretics. He described the ways of their deceit:

They study, then, to appear good in order to do injury to the good, and shrink from appearing evil that they may thus give their evil designs fuller scope. For they do not care to cultivate virtues, but only to colour their vices with a delusive tinge of virtues. Under the veil of religion, they conceal an impious superstition; they regard the mere refraining from doing wrong openly as innocence, and thus take for themselves an outward appearance of goodness only. For a cloak to their infamy they make a vow of continence. (Mabillon & Eales, 1896, p 390)

In 1145 Bernard journeyed to Toulouse to challenge the teachings of the Henricians and to bring them heretics back to the teachings of the Church. The heretics refused to listen to him.

In 1184, Pope Lucius III, dismayed by the prevalence of heresy, issued the bull Ad abolendam diversam haeresium pravitatem (To abolish diverse malignant heresies). This initiated (or formalized) the Episcopal Inquisition: local bishops were empowered to try suspected heretics. Once convicted, heretics were handed over to secular authorities for appropriate punishment. The church did not wish to sully itself with their death.

Heretics were executed in various ways. However, the most common sentence was burning. The first such sentence to be carried out since ancient times was at Orleans in 1022 under Robert II (also known as the “pious”), King of the Francs. The fire gave the heretics a foretaste of hell “enacting in miniature the fate that awaited all those who failed to take their place within a united Christian society” (Barbezat, 2014; see also Barbezat 2018). An illumination from the Chroniques de France (1487) in the British Library shows the burning of the heretics. Noteworthy is the idyllic landscape in the backgound, and the complacency of the king and his followers.

Catharism

Many of the heretics, such as those in Cologne and in the South of France, were called “Cathars.” The name perhaps derives from the Greek katharoi (pure ones), but the word may also have described the worship of Satan in the form of a cat. The heretics did not use the term; rather, they considered themselves “good men” (bons omes in the Occitan language of the South of France).

Most of what we know about the Cathars comes from the writings of the Inquisitors. The books and manuals that the heretics may have followed were burned. In recent years there has been much discussion and dispute (e.g., Frassetto, 2006; Sennis, 2016) about whether the Cathars were a linked group of believers (in essence a church) or whether that idea was a paranoid construct of the Inquisition used to establish terror and maintain the power of the established Church. Skeptics thus believe that a Cathar was anyone who disagreed with the teachings of the Catholic Church (Moore, 1987, 2012; Pegg, 2001). The more traditional view, followed in this posting, is that the Cathars were a specific congregation of beleivers linked to other sects such as the Bogomils in Bulgaria (e.g. Hamilton, 2006; Frassetto, 2008).

The Cathars were dualists, both ontologically – spirit and matter were distinct and antithetical – and theologically – one god created the spiritual world and a separate god created the material universe. In these beliefs they followed a long line of Christian heretics. The Gnostics of the 2nd Century CE often considered the world in these terms. In the 3rd Century CE the Parthian prophet Mani taught that the spiritual world of light was separate from the material world of darkness. His followers believed that he was the reincarnation of earlier teachers such as Zoroaster, Buddha and Jesus. Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 CE) was a Manichaean before he converted to orthodox Christianity. In the 8th and 9th Centuries CE, a group of dualists called the Paulicians flourished in Armenia. In the 10th Century CE, followers of the priest Bogomil (“dear to God” in Slavic) established in Bulgaria a sect of dualist believers that called themselves by the name of their leader (or vice versa). The Bogomils (Frassetto, 2007, Chapter 1) were condemned as heretics by both the Roman and the Eastern Churches but they persisted in their beliefs, and some of them travelled to Italy, Germany and France. A lost manuscript purportedly describes a meeting in 1167 between a Bogomil priest named Nicetas from Constantinople and several Cathar believers in Saint Félix near Toulouse (Frassetto, 2007, p 78). The authenticity of the document has been questioned, but the idea rings true.

The main beliefs of the Cathars were described by the Cistercian monk Peter of Vaux-de-Cernay who was with the army of Simon de Montfort during the Albigensian Crusade (Wakefield & Evans, 1991, pp 235-241), and are detailed in the 1245 testimony of Rainerius Sacconi, an Italian Cathar who converted and became a Dominican (Wakefield & Evans, 1991, pp 329-346) and in The Book of Two Principles written by an Italian Cathar, John of Lugio in the mid 13th Century CE (Wakefield & Evans, 1991, pp 522-591). Oldenbourg (1961), Roquebert (1999), O’Shea (2000), Smith (2015) and McDonald (2017) provide modern summaries:

(i) Dualism: The Cathars believed that there were two worlds – spiritual and material – and that each world had its own god. Human beings were spiritual entities imprisoned in the flesh. The spiritual world was the “Kingdom of Heaven” that Jesus described in his beatitudes and parables. In answer to Pilate’s asking him whether he was King of the Jews, Jesus had stated “My kingdom is not of the world.” (John 18:26)

(ii) Reincarnation. At death the soul migrated in another body. Such an idea is widespread in the religions of the East. There is no separate afterlife, no heaven or hell. Although the life of the flesh may itself be considered hell.

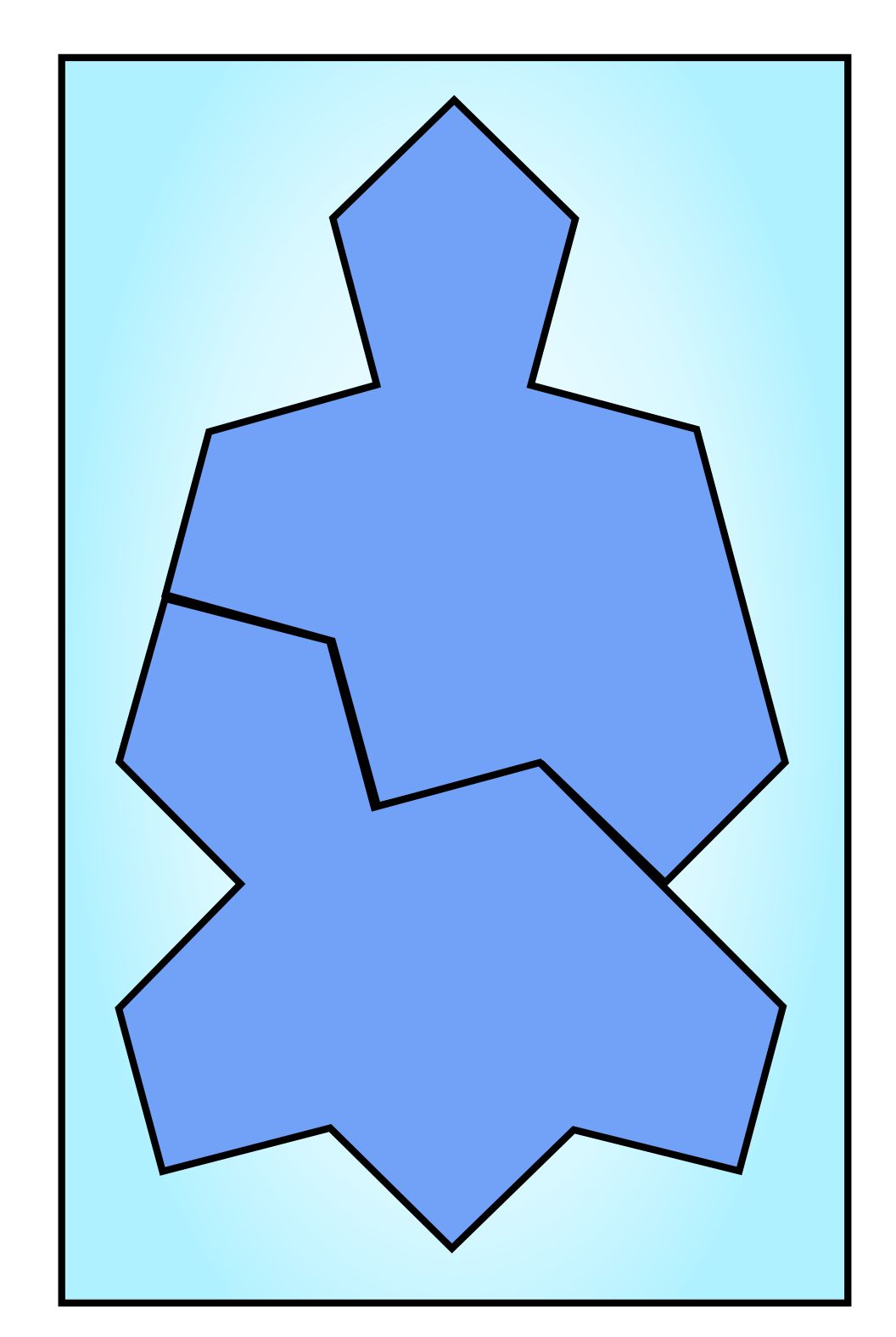

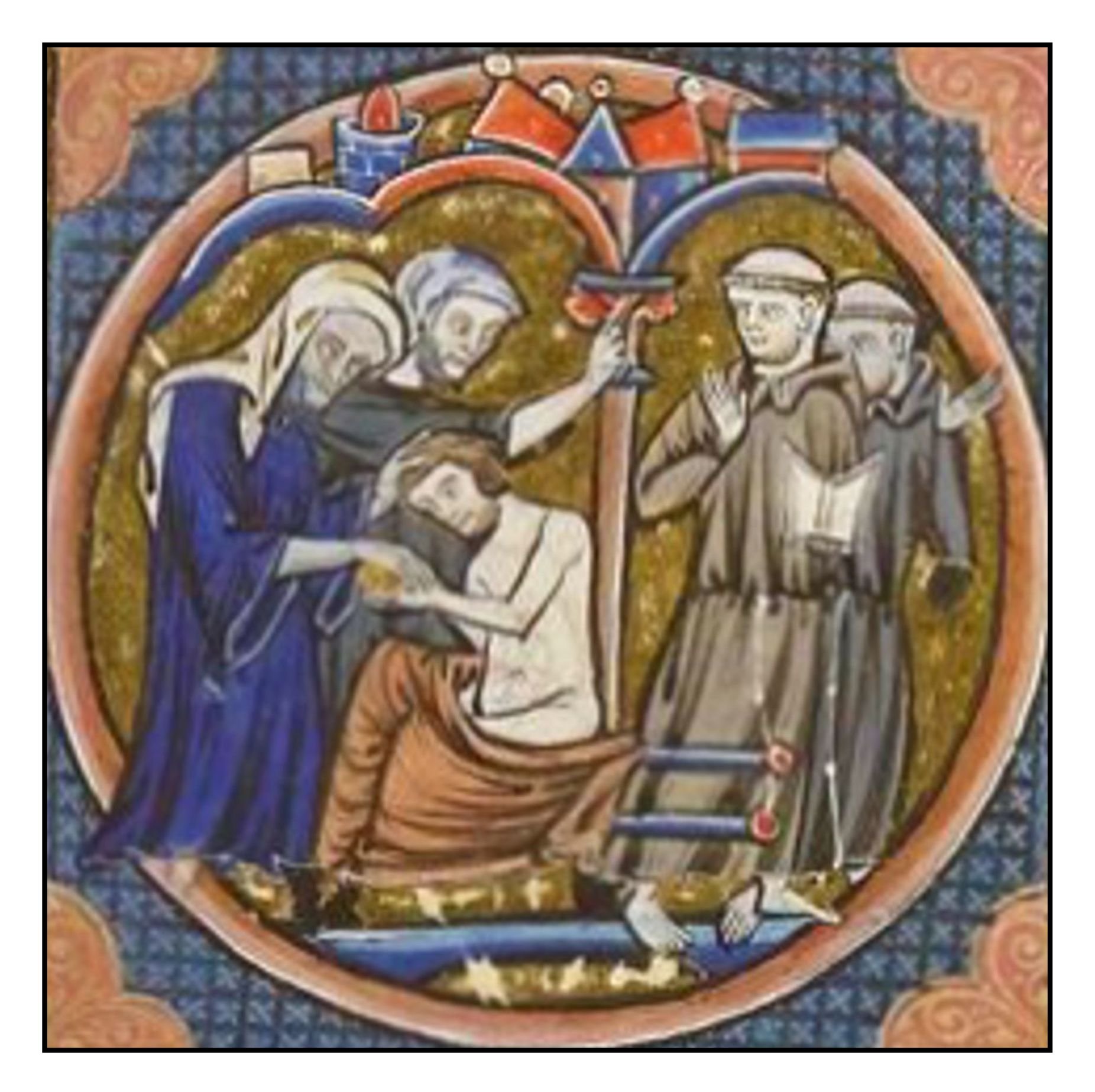

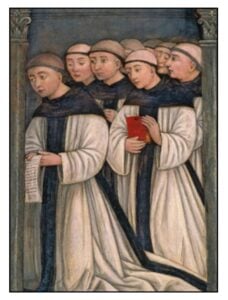

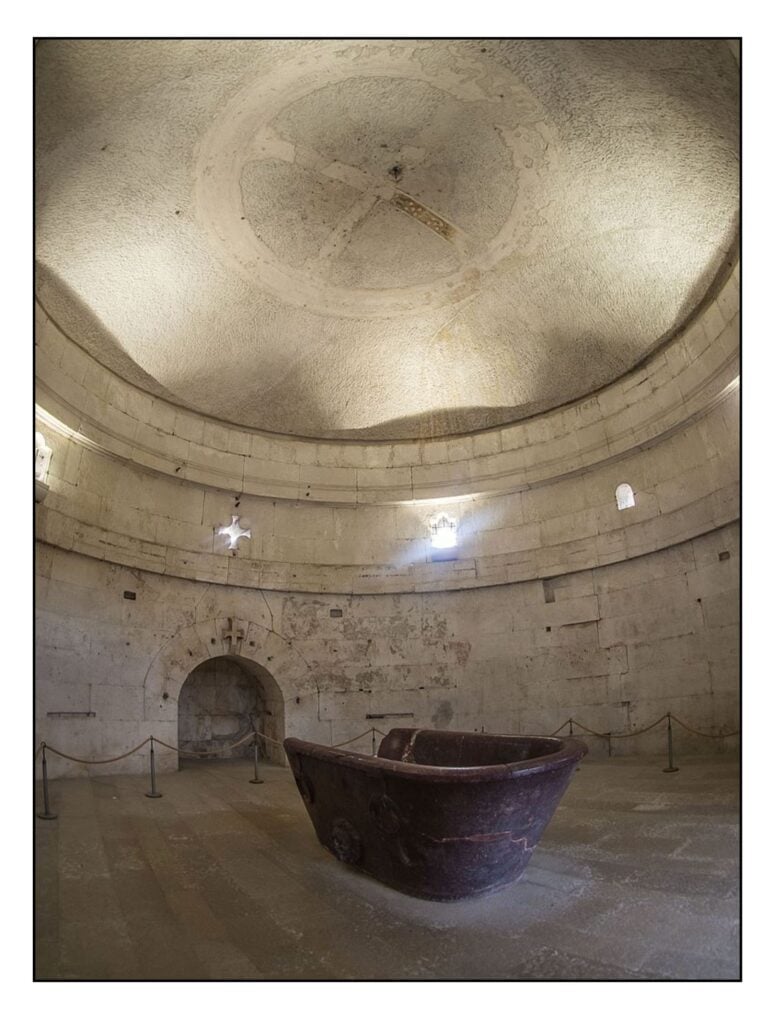

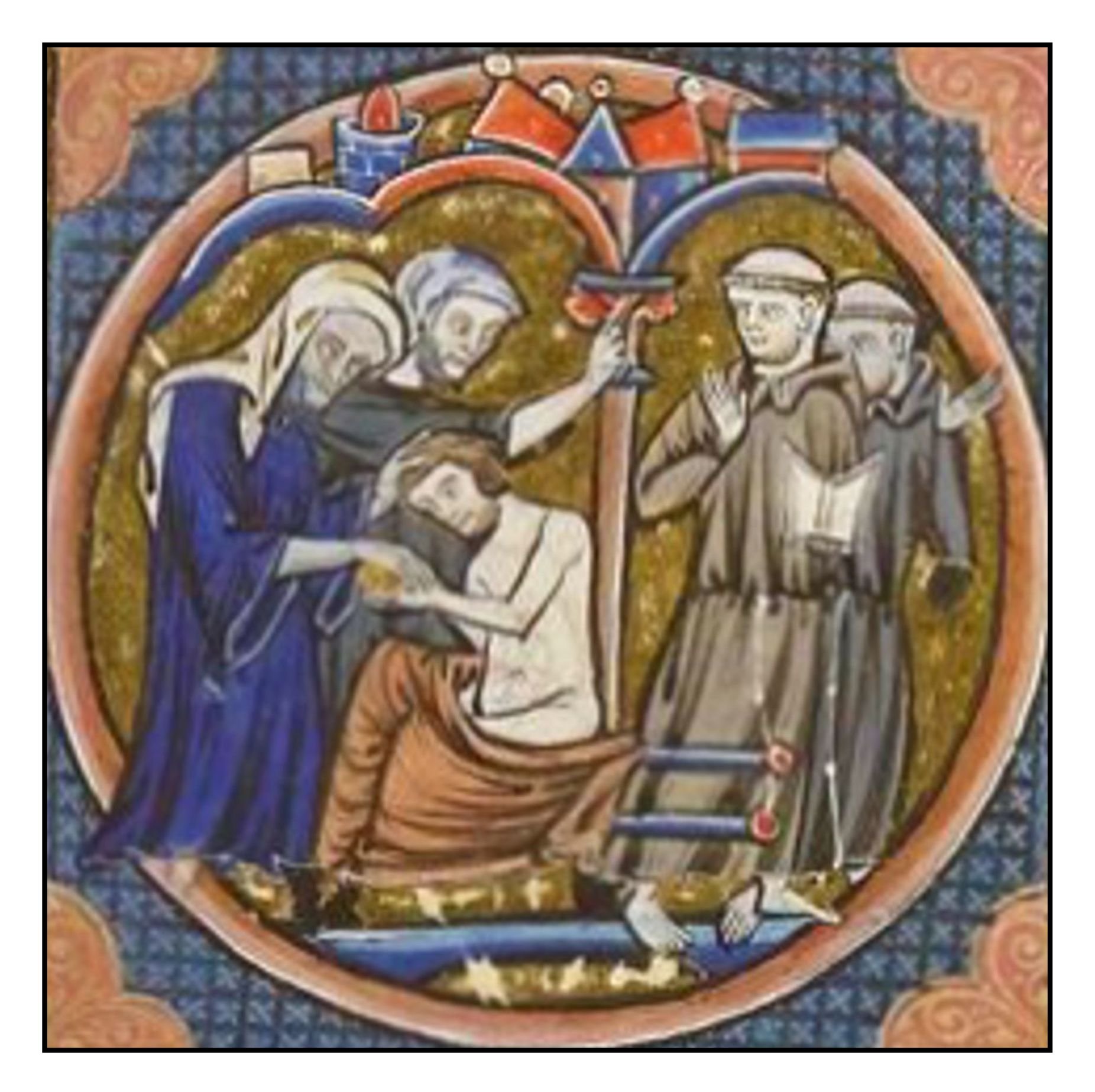

(iii) Consolamentum. If a believer wished to escape the eternal cycle of reincarnation, he or she could decide to live a pure life, abstaining completely from material goods and desires. Such people were called Perfects. The decision to become a Perfect was enacted through the ceremony of consolamentum, wherein one already a Perfect laid hands on the head of a believer who aspired to the life of purity. This was the baptism of fire. The illustration at the right shows an illumination from a 13th Century Bible in the Bibliothèque nationale de France: two Franciscan monks stand aghast at witnessing a ceremony of consolamentum.

If the Perfects maintained their state of purity, at death they would be released from reincarnation and united with the spirit of the good God. However, any lapse from the pure life – eating meat or any of the products of procreation (milk, eggs), indulging in sexual intercourse – would render them (and whomever they had provided consolamentum) no longer Perfect.

(iv) Apostolic Life: The Cathars followed in the basic teachings of Jesus. They used the Lord’s prayer. They believed a compassionate life dedicated to the benefit of their fellows and in the rejection of all worldly possessions. In the latter they followed the injunctions of Jesus:

Lay not up for yourselves treasures upon earth, where moth and rust doth corrupt, and where thieves break through and steal:

But lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust doth corrupt, and where thieves do not break through nor steal:

For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. (Matthew 6: 19-21)

(v) Denial of Church Dogma: Although they believed in the ethical teachings of Jesus, the Cathars rejected most of the teachings and sacraments of the Catholic Church. They denied the baptism by water, preferring the true baptism by fire. They refused the sacrament of marriage since they thought that procreation only served to maintain the endless cycle of reincarnation. They had no patience with the Trinity, and were uncertain about whether Jesus was God incarnate. Many of the Cathars in the South of France believed that Jesus was human and was married to Mary Magdalene.

(vi) Oaths: The Cathars refused to take oaths. In this they were following the instructions of Jesus

But I say unto you, Swear not at all; neither by heaven; for it is God’s throne:

Nor by the earth; for it is his footstool: neither by Jerusalem; for it is the city of the great King.

Neither shalt thou swear by thy head, because thou canst not make one hair white or black.

But let your communication be, Yea, yea; Nay, nay: for whatsoever is more than these cometh of evil. (Matthew 5: 34-37)

This was a severe problem in a feudal society, wherein all relations depended upon oaths of fealty.

(vii) Role of women: The Cathars denied that women should be subordinate to men. Many Cathar Perfects were women.

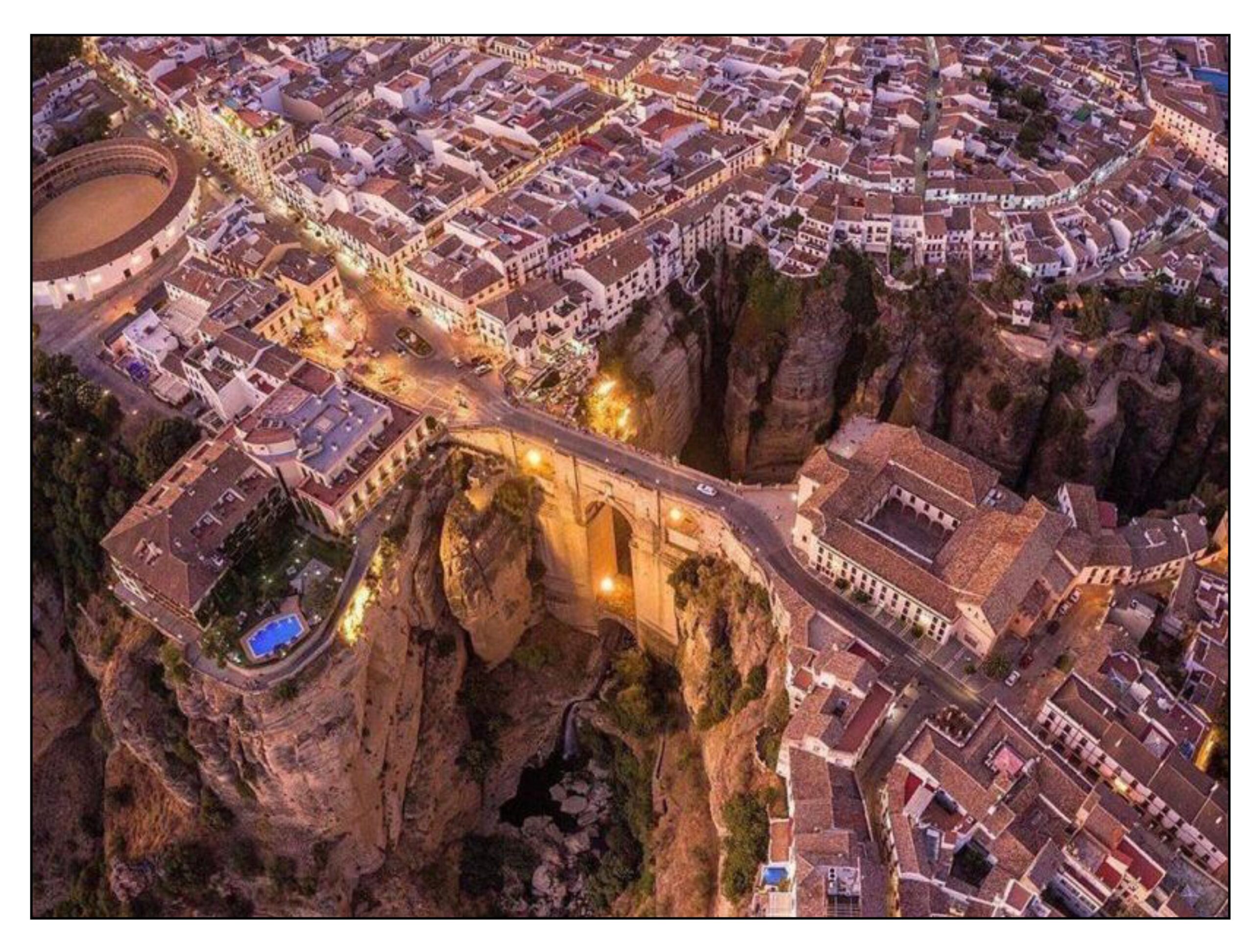

Languedoc

By the end of the 12th Century the Cathar heresy had become widespread in the South of France. The language spoken in this region was Occitan or the langue d’oc. This Romance language used oc to mean “yes,” unlike French or langue d’oïl which used oïl (later oui) or Spanish which used si. Each region spoke its own dialect of Occitan, the most prominent of these being Provençal in the east and Gascon in the west.

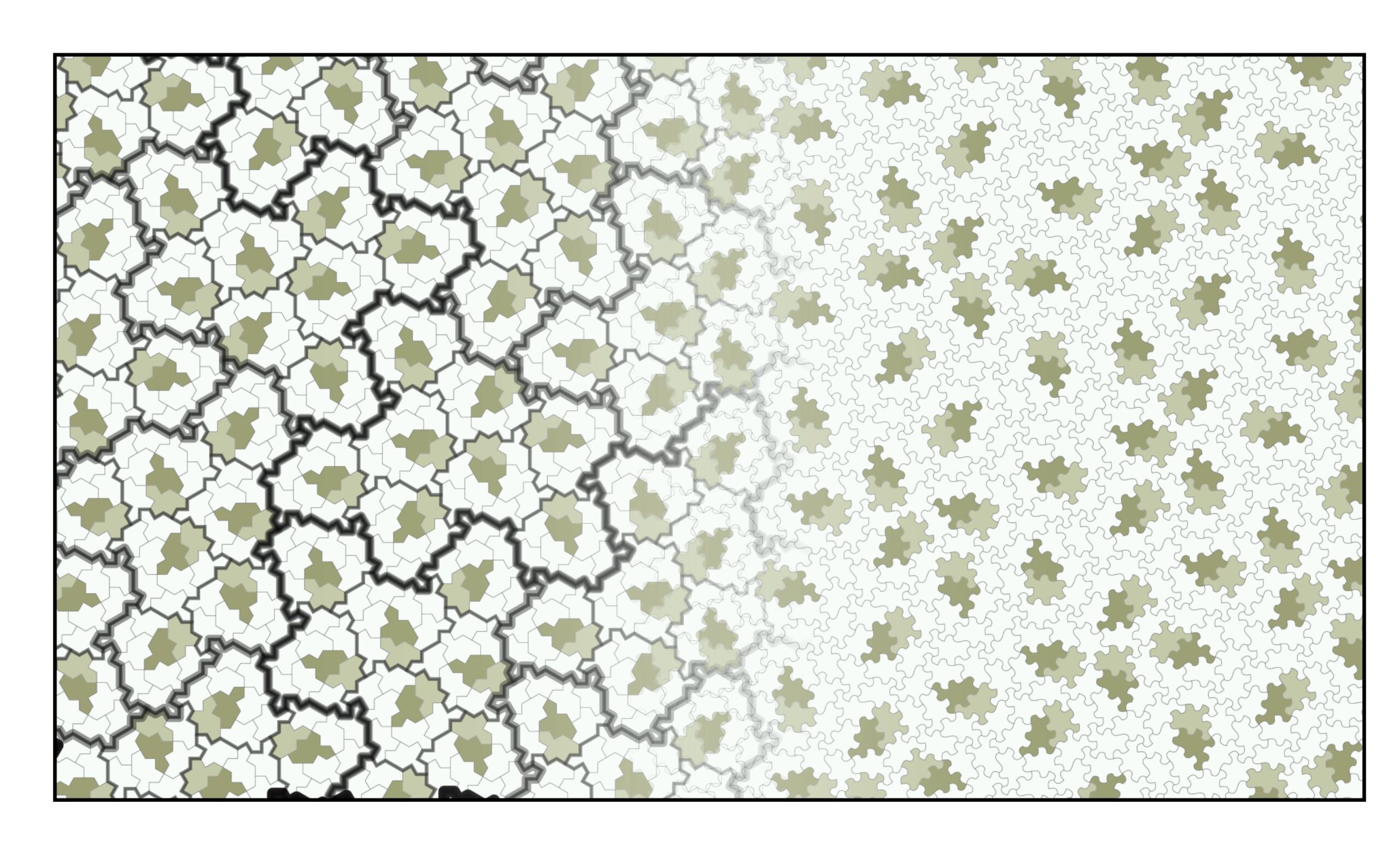

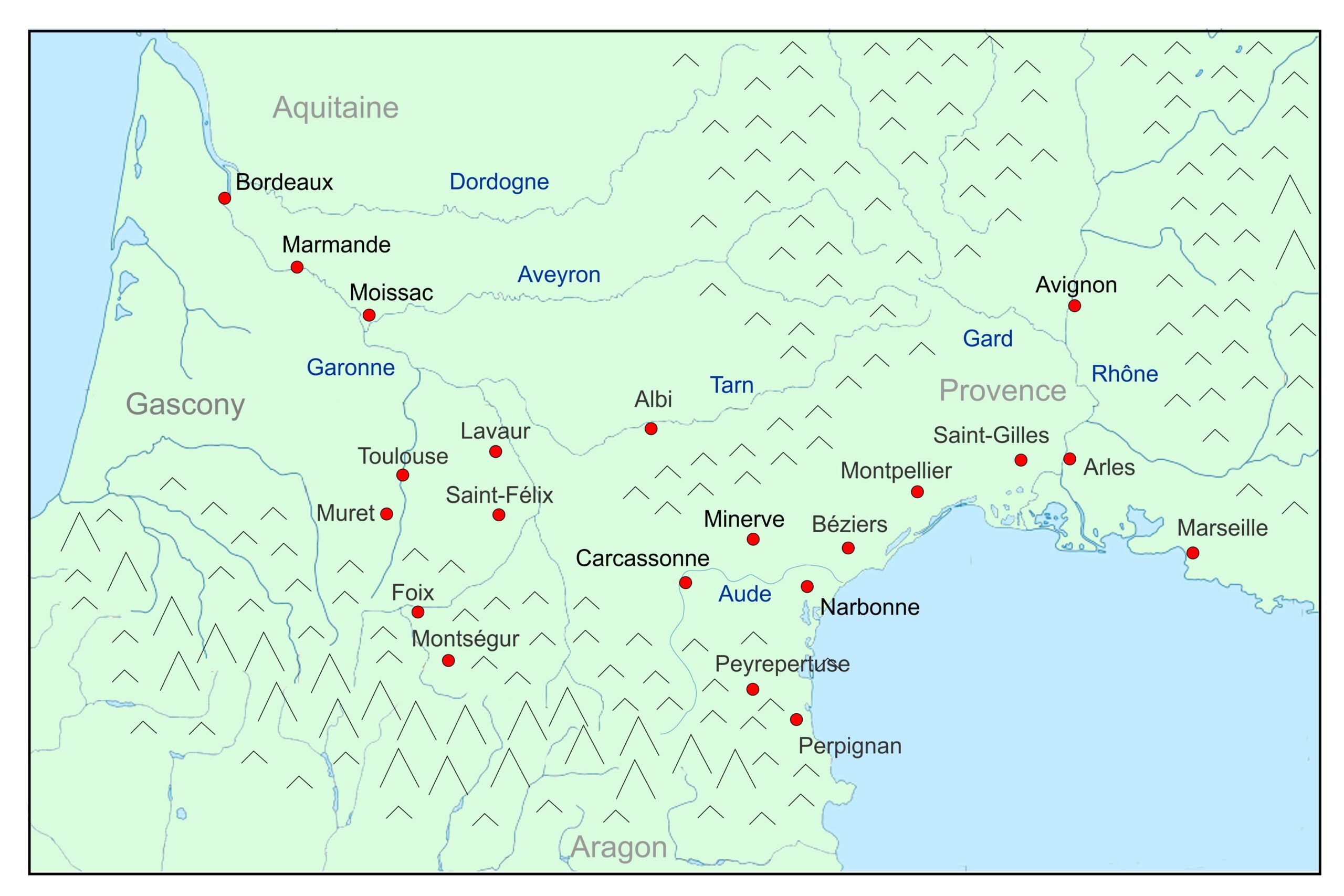

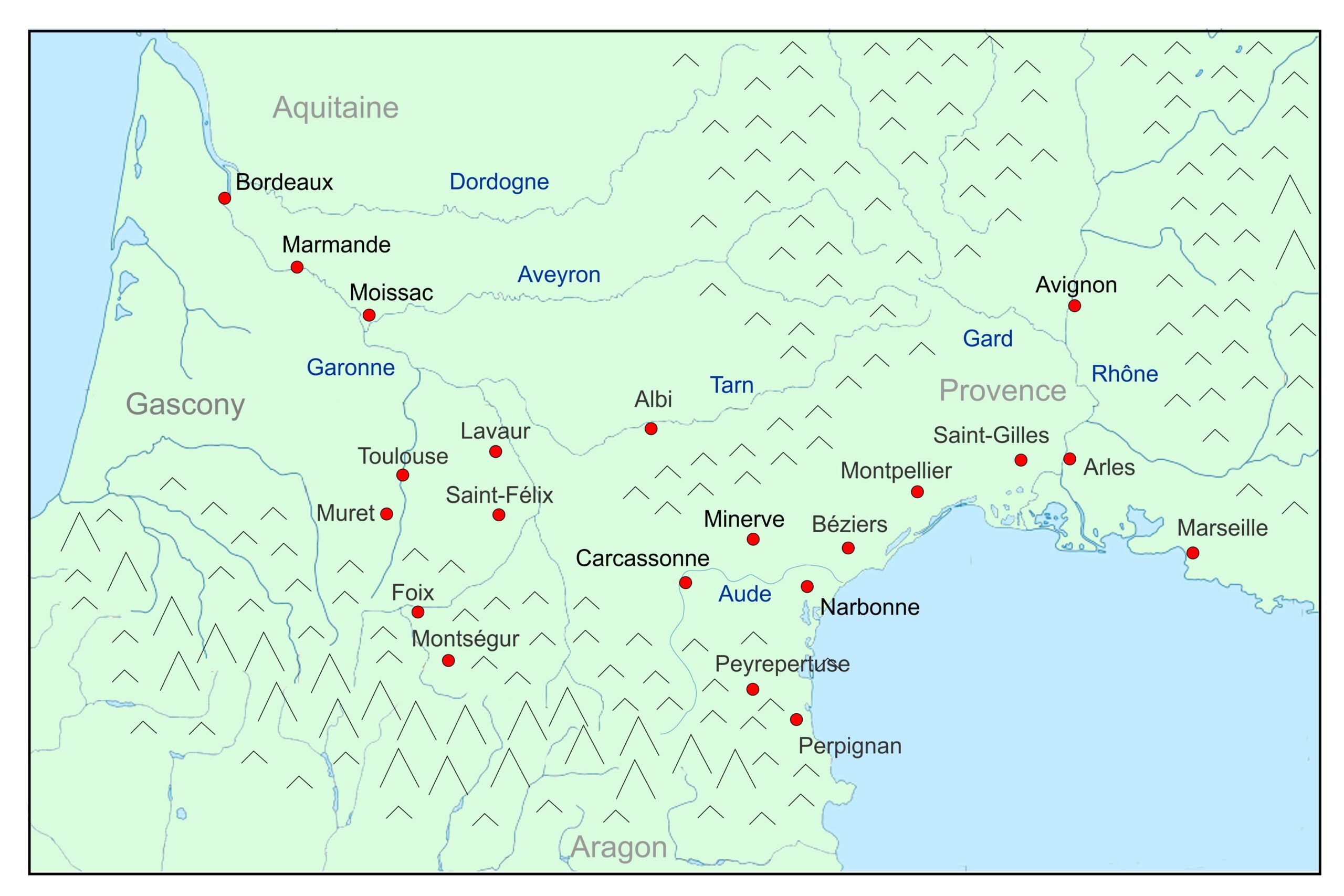

At that time, the Languedoc region, named after the language, was a patchwork of different political entities. The most prominent leader was Raymond VI of the Saint-Gilles family which controlled Toulouse and regions in Provence. Raymond-Roger II Trencavel governed the region of Carcassonne and Bézier. Raymond-Roger of Foix in the foothills of the Pyrenees was an important ally of Toulouse. His wife and sister had both become Cathar Perfects. All these leaders had feudal ties to Pedro II, King of Aragon in Northern Spain. The illustration below shows a map of the region:

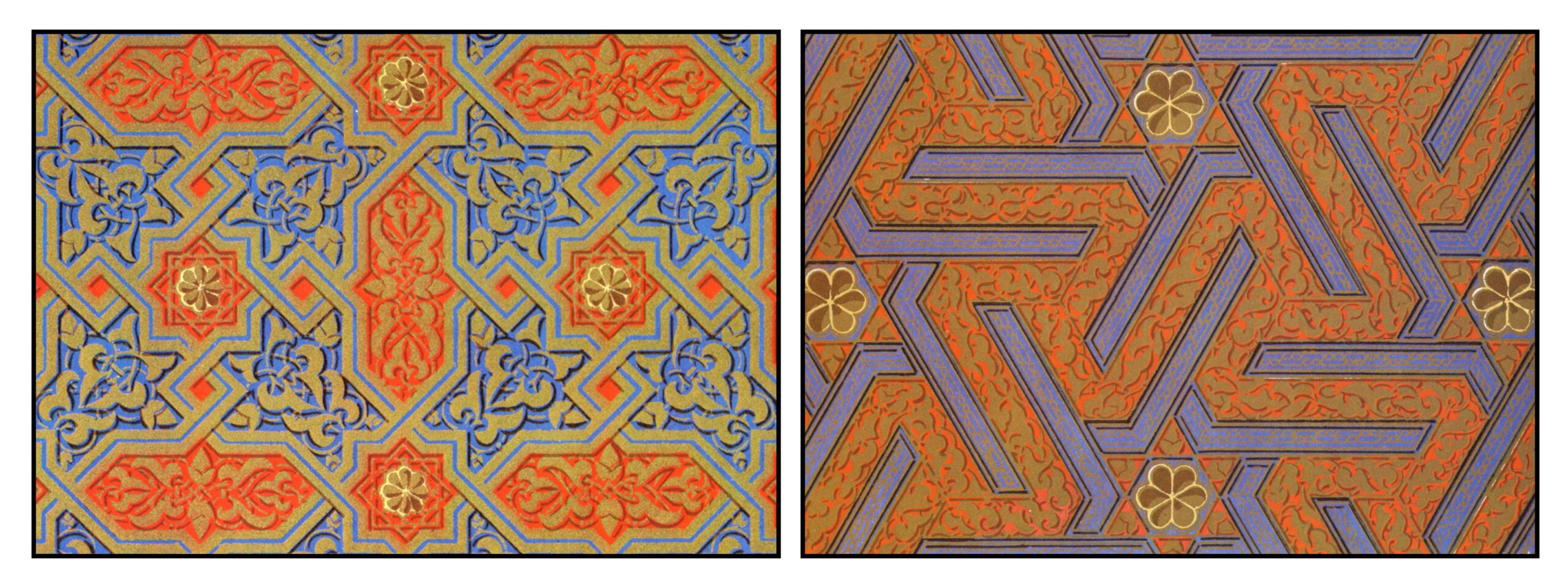

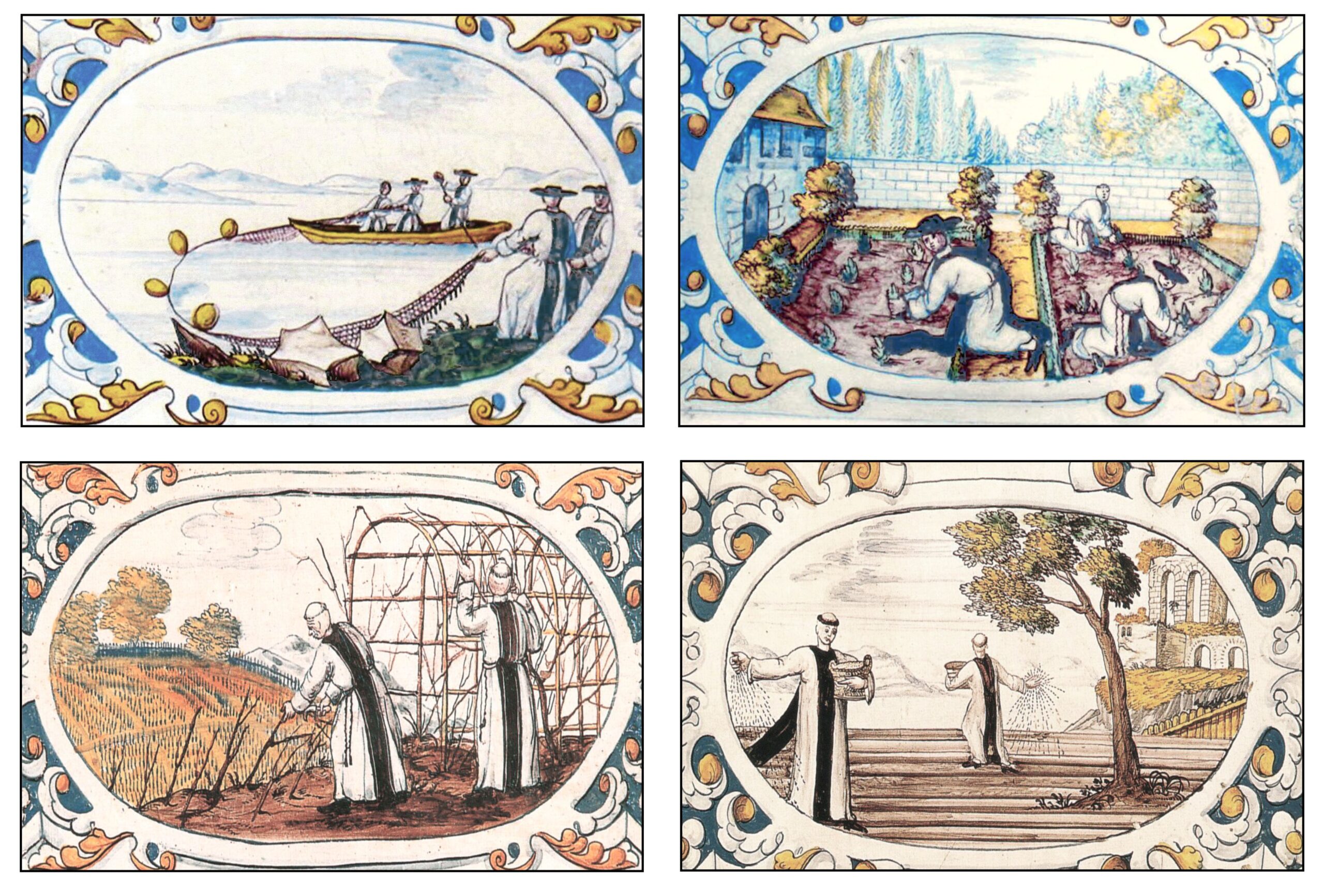

Languedoc was flourishing. The land produced a bounty of wine, olive oil, and wool. Weavers abounded and cloth merchants became rich. The region was a major trading crossroads linking Spain and the Mediterranean to the North and West of France. Its leaders fostered tolerance. A large Jewish society fostered both trade and new learning. Much of the medieval development of the Kabbalah occurred in Provence and in Northern Spain (Boboc, 2009).

Life was to be enjoyed. Time was available for chivalry and courtly love. The poetry of the troubadours (Chaytor,1912; Paterson, 1993) brought the rhymes and rhythms of Arabic poetry into the literature of romance languages. Dante called the Occitan poet Arnaut Daniel il miglior fabbro (the best [word]smith), and Petrarch called him the gran maestre d’amore. The following are a few lines with translation by Ezra Pound:

Tot quant es gela Though all things freeze here

Mas ieu non puesc frezir I can naught feel the cold

C’amors novela For new love sees here

Mi fal cor reverdir My heart’s new leaf unfold.

Pope Innocent III

In 1198 Lotario dei Conti di Segni became Pope Innocent III. He was aware of the dissension in the church and initially sympathetic to those who criticized priestly affluence. During his reign (1198-1216), he founded two new medicant orders: the Franciscans led by Francis of Assisi in 1209 and the Dominicans led by Domingo Félix de Guzman in 1216. The illustration below shows frescoes of Saint Francis (by a follower of Giotto c. 1300; Innocent III by and anonymous artist, c 1225 and Saint Dominic by Fra Angelico, c. 1440).

In 1202 Innocent III initiated the disastrous Fourth Crusade to the Holy Land. The crusaders, attracted by the hope of plunder and egged on by the Venetians, sacked Constantinople instead of freeing the Holy Land. Only a few crusaders refused to participate in the sack and travelled on to Palestine, among them Simon de Montfort.

Innocent III was particularly concerned by the Cathars in Languedoc and urged Raymond VI of Toulouse to contain their heresy. He sent many priests, among them Saint Dominic, to dispute with the heretics and to urge them to return to the church. Their efforts were to no avail. The following illustration shows two paintings by Pedro Berruguete from about 1495. The left represents a legendary meeting between Dominic and the Cathars. Books of Cathar and Catholic teachings were submitted to trial by fire. Only the teachings of the Catholic Church were miraculously preserved and rose above the assembled disputants. On the right Dominic presides over an auto-da-fé (Portuguese, act of faith) for the burning of heretics. However, there is no evidence that the saint participated in any trials of the heretics: he died in 1221 long before the Papal Inquisition was established in 1231. Berruguete’s paintings were commissioned by the Spanish Inquisition founded in 1475. That institution with its frequent autos-da-fé was sorely in need of a founding saint, and was more concerned with terror than with truth.

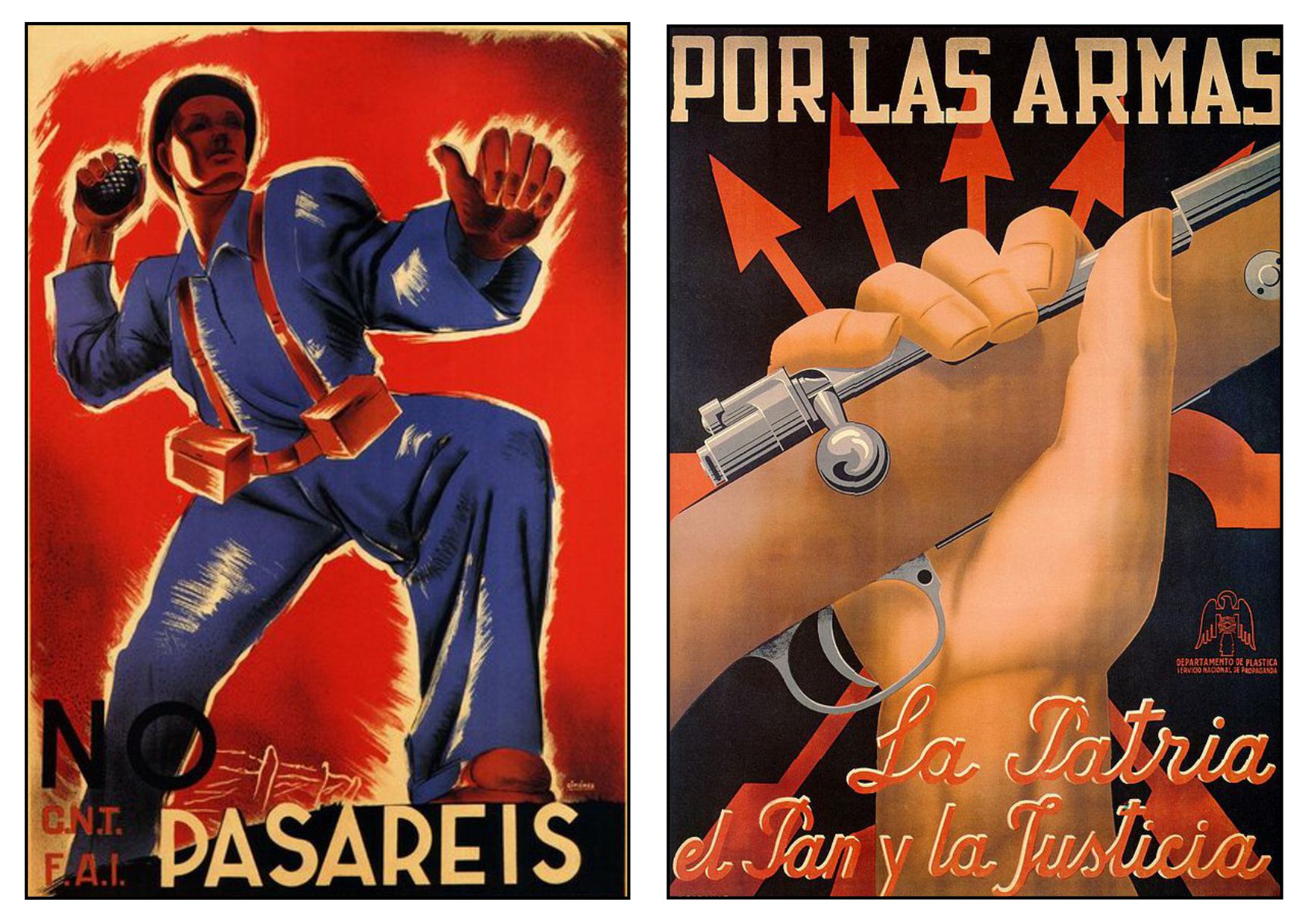

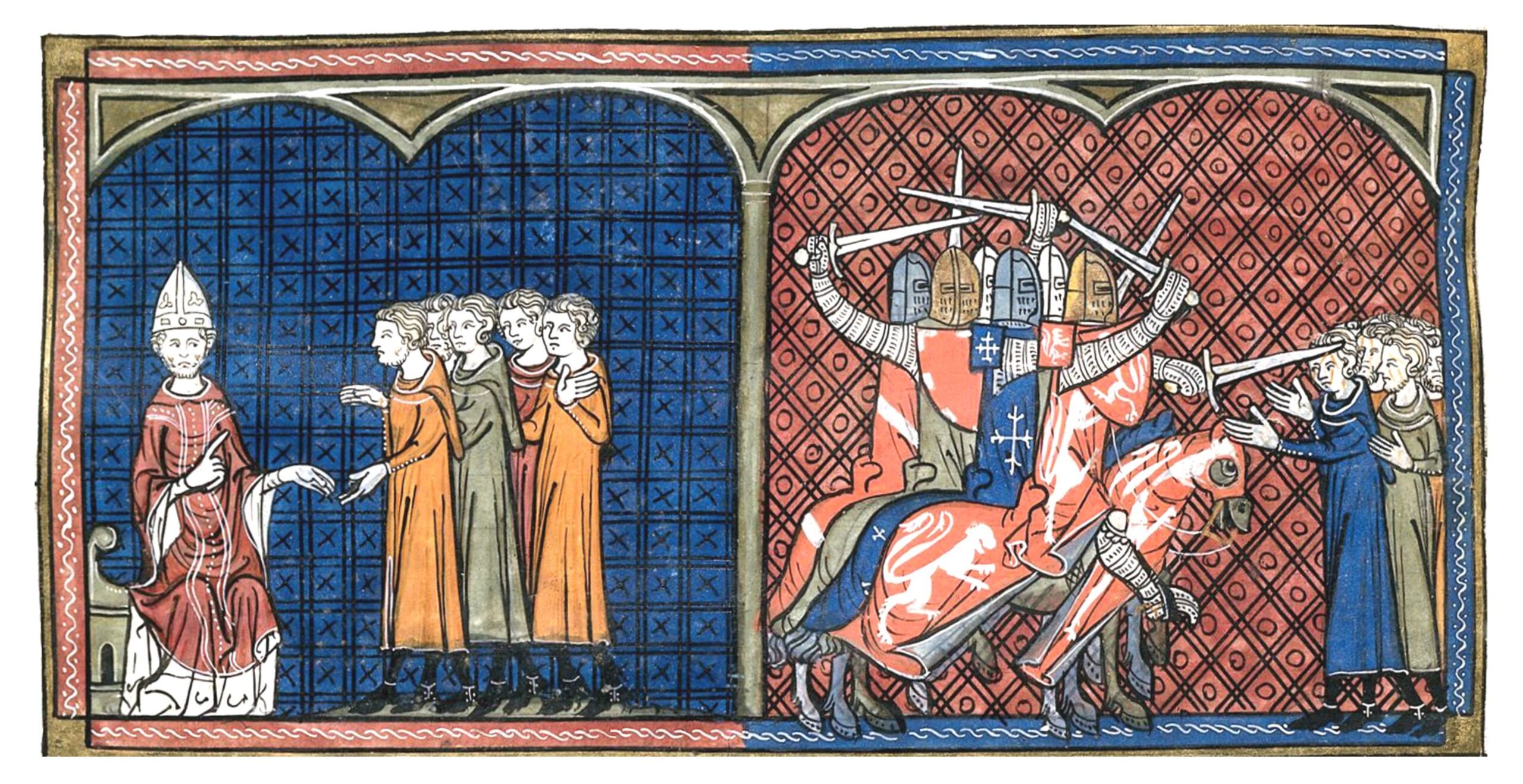

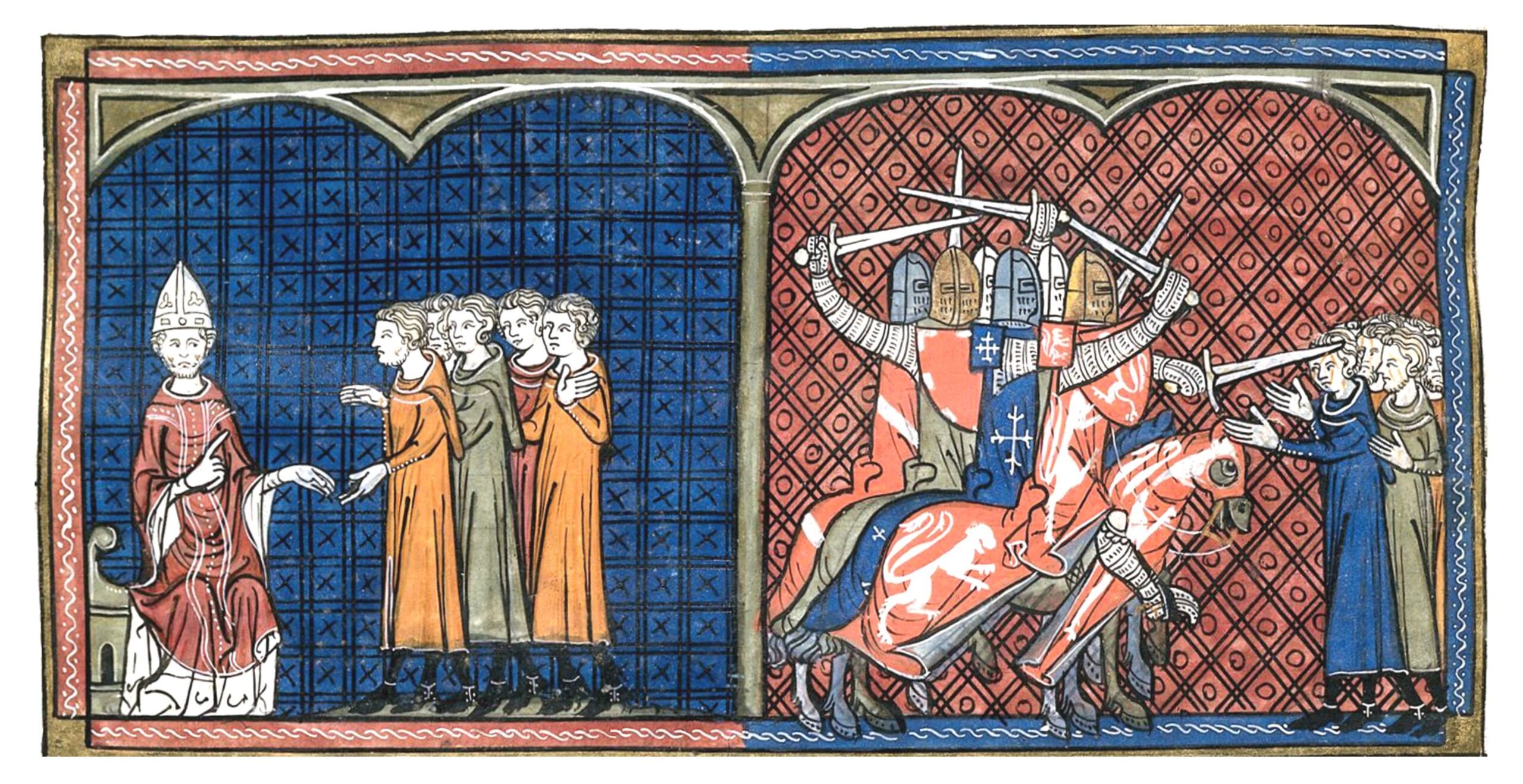

In 1207 the papal legate, Pierre de Castelnau, excommunicated Raymond VI of Toulouse. In January of 1208 Pierre negotiated with Raymond at Saint-Gilles but refused to absolve him. Pierre was then murdered at the Rhône River as he travelled back to Rome. No one knows who ordered his assassination but Raymond was held responsible. Raymond submitted to being scourged as penance for the death in June of 1209. However, by then the Pope had already called for a Crusade against the Cathars (or Albigensians) and Christian knights from the North of France had rallied to the cause, driven as much in hope for power and plunder as by desire to defend the faith. The Crusaders were led by the knight Simon IV de Montfort and by Arnaud Amaury (or Almaric), the 17th abbot of Cîteaux, mother house of the Cistercians. The following illustration from the Les Grandes chroniques de France (14th Century, folio 374) now in the British Library shows Innocent III excommunicating the Cathars and the subsequent Albigensian Crusade.

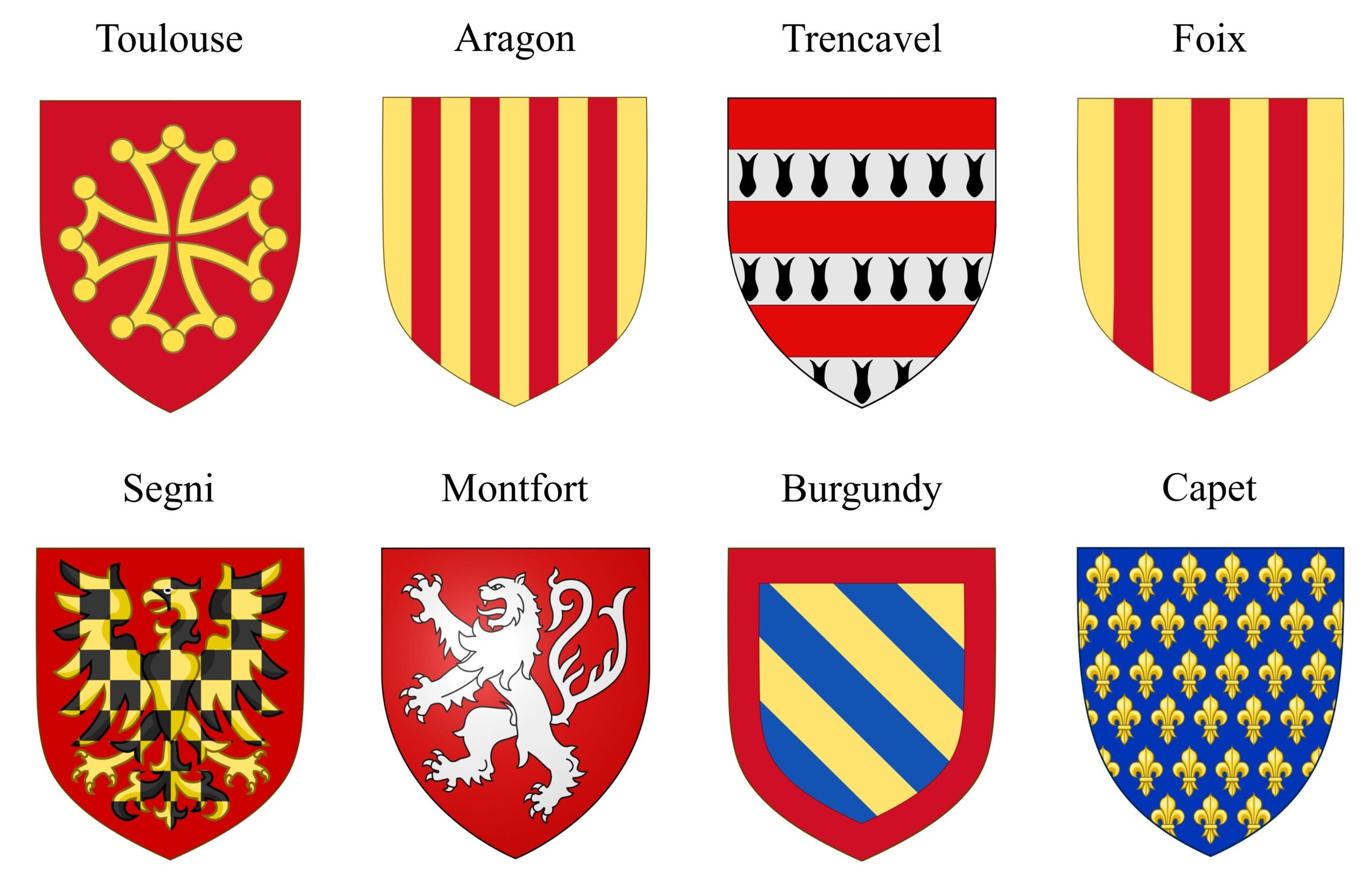

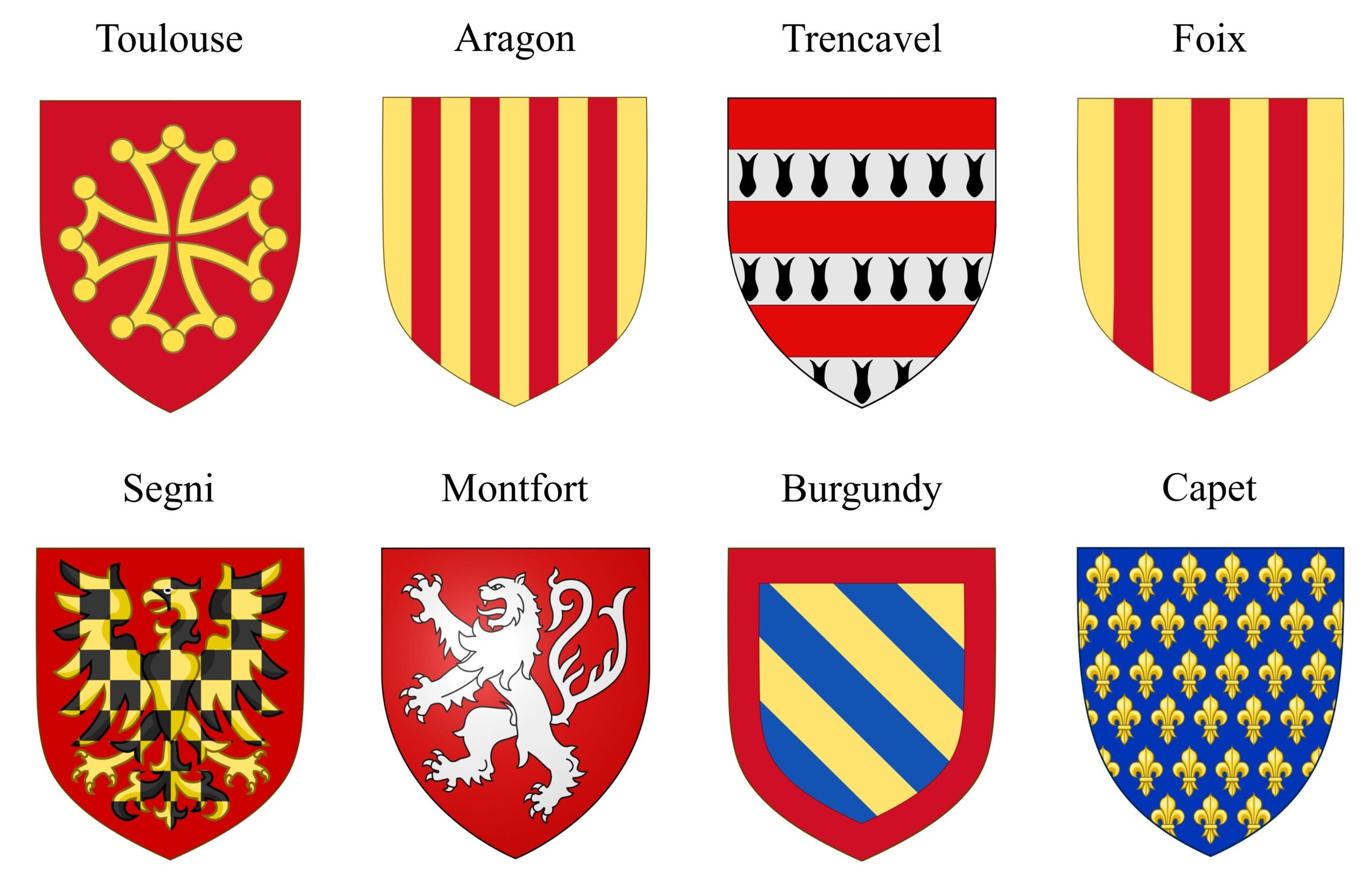

Below are shown the coats of arms for the participants in the Albigensian Crusade. The upper line shows the powers of Languedoc and Aragon; the lower line the crusaders. The Pope’s arms would have added a papal tiara and the keys of Saint Peter to the basic arms of the house of Segni. The kings of the Francs were from the house of Capet.

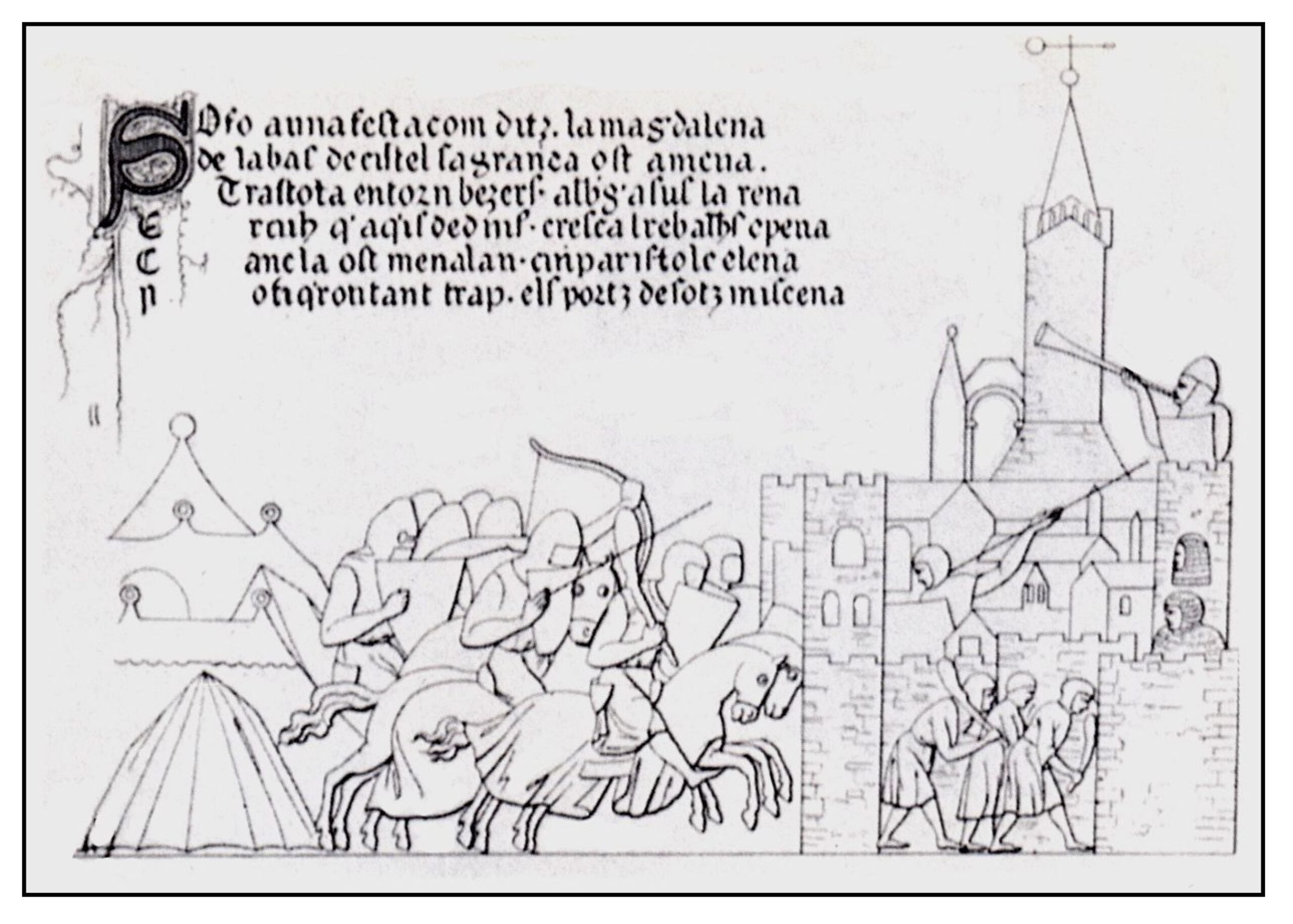

Béziers

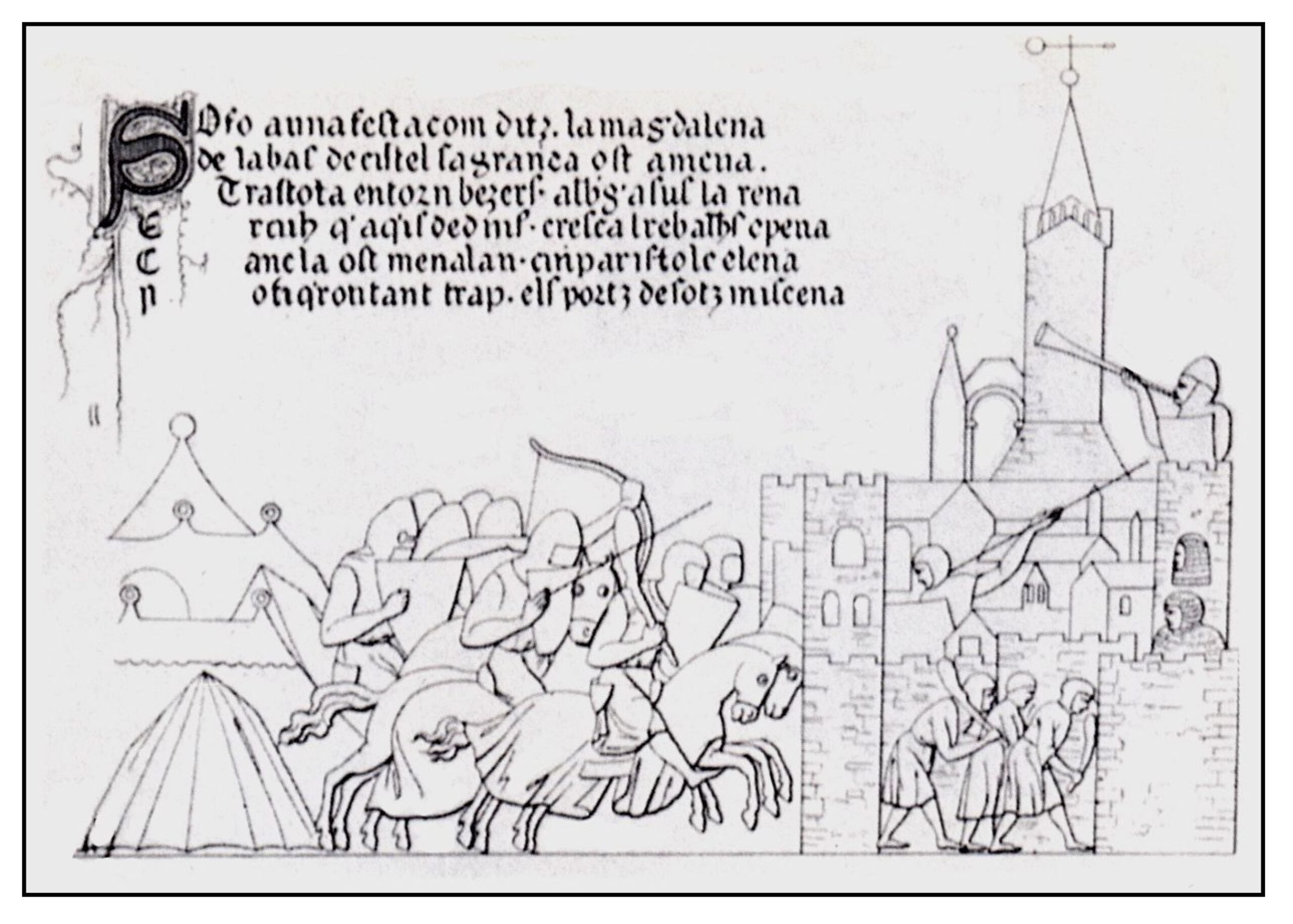

The first engagement of the Crusaders was the siege of Béziers, whose citizens were Catholic Cathar and Jew. The huge army encamped outside the city walls on July 22, 1209, the feast day of Mary Magdalene. The following picture is from the manuscript of the Canso de la Crozada (Shirley 2016). This epic poem was begun by Guillaume de Tudela and completed by another anonymous troubadour. The writing was likely finished by 1219 (the date of the last event it records), but the only extant manuscript comes from 1275. The illustrations were outlined in preparation for painting but, although the decorated initials beginning each section (or laisse) were illuminated, the outlines never were. (The actual illustration is from an engraving based on the drawing – the manuscript drawing is very faint):

The text in Occitan can be translated as:

On the feast of St Mary Magdalen, the abbot of Cîteaux brought his huge army to Béziers and encamped it on the sandy plains around the city. Great, I am sure, was the terror inside the walls, for never in the host of Menelaus, from whom Paris stole Helena, were so many tents set up on the plains below Mycenae (Shirley, 2016, laisse 18)

A minor skirmish between the defenders and the besiegers led to the gates of the city being left open. The camp followers and mercenaries stormed through and began looting the city. The knights followed. The result was a massacre. Various reports numbered the dead as anywhere between 10,000 and 20,000 people. No distinction was made between Catholic and Cathar. Everyone died.

A Cistercian chronicler later reported that Arnaud Amaury was afraid that the Cathars in the city would falsely claim to be pious Catholics and escape to spread their heresy. When asked how to distinguish between believer and heretic, he is reported to have said Caedite eos. Novit Dominus qui sunt eius (Kill them all. The lord knows those that are his own). This may not be true, but he would have been familiar with the words, which derive from a verse in the New Testament describing how only true believers go to heaven.

Nevertheless the foundation of God standeth sure, having this seal, The Lord knoweth them that are his. And, let every one that nameth the name of Christ depart from iniquity. (II Timothy 2:19)

Carcassonne

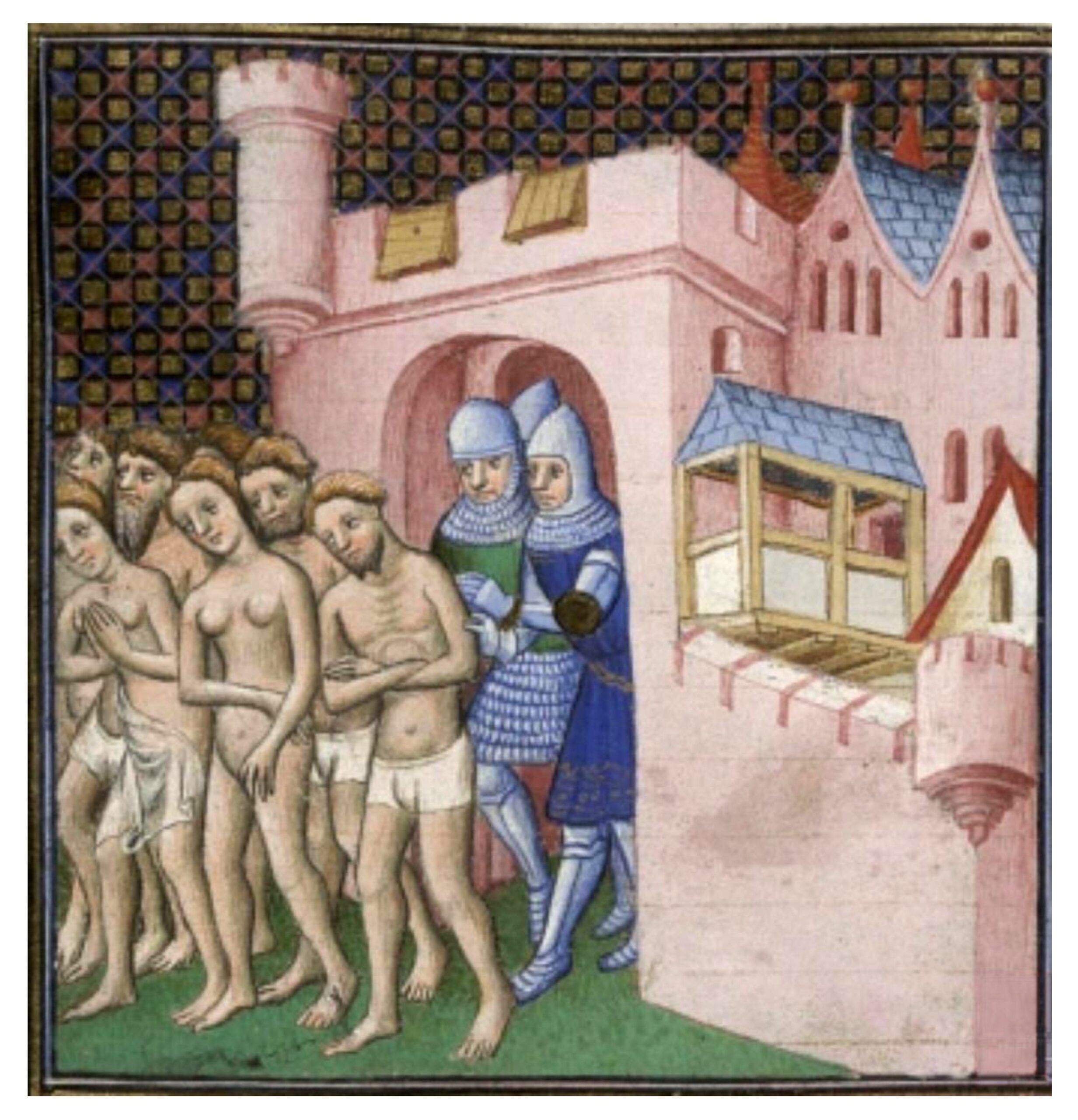

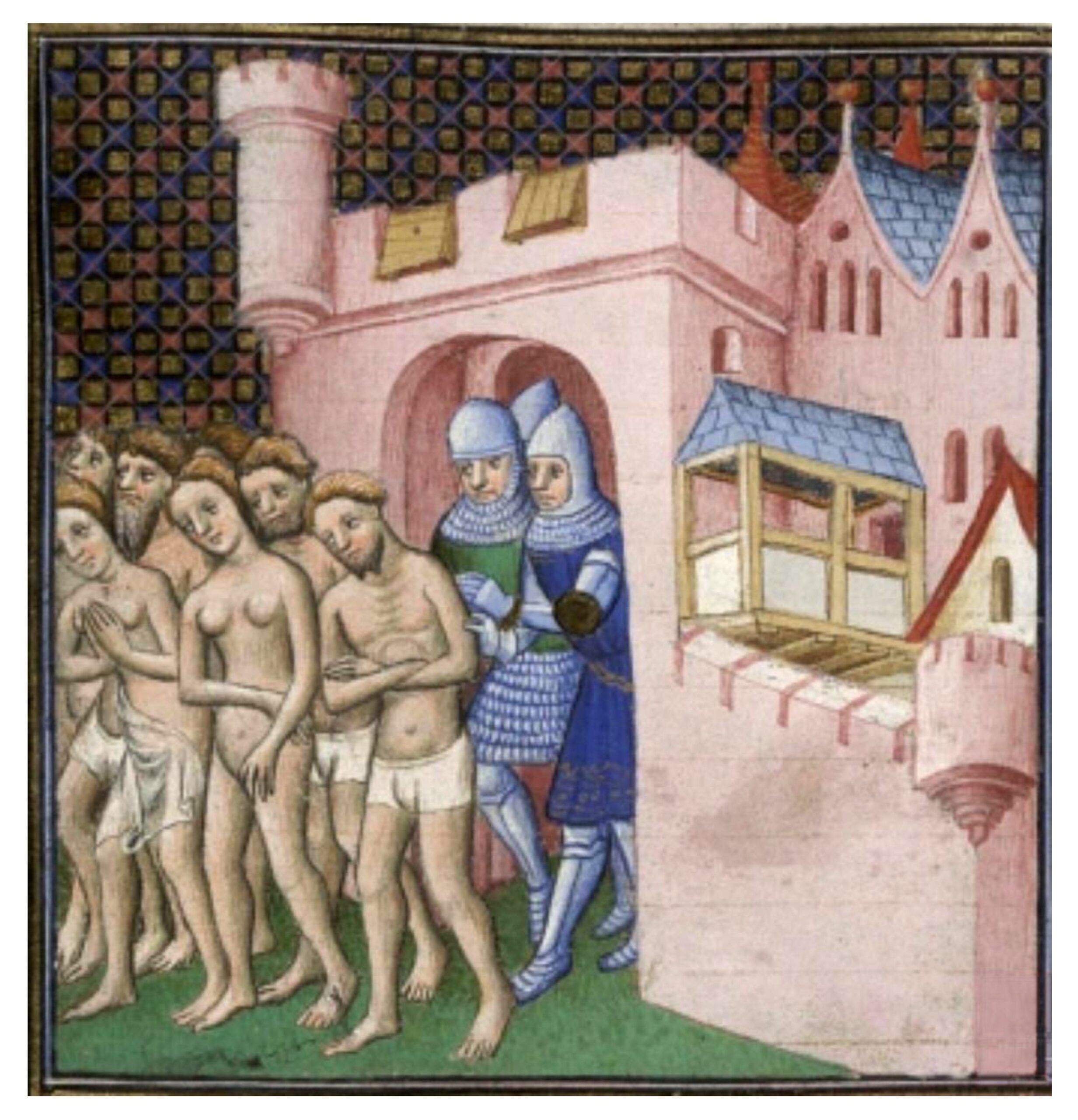

The Crusaders then moved on and laid siege to Carcassonne on the banks of the Aude River. The city lacked its own supply of water and could not hold out for long. Under promise of safe conduct Raymond-Roger Trencavel therefore negotiated the surrender of the city. All the citizens of the city were spared but they were forced to leave without taking anything with them. The illustration on the right from Les Grandes chroniques de France shows them leaving the city without even the clothes on their back. Simon de Montfort was granted dominion over Carcassonne and Béziers. Raymond-Roger was imprisoned in his own dungeon in Carcassonne and died there within a few months.

Mass Burnings

After Carcassonne, the army moved on to besiege other Languedoc towns and cities. After a month of siege in 1210, Simon de Montfort accepted the surrender of Minerve, and agreed to spare its inhabitants. However, Arnaud Amaury insisted that they should all be asked to swear allegiance to the Catholic Church. One hundred and forty Cathar Perfects refused and were burned at the stake outside the town. This was the first of the many mass immolations that would recur throughout the crusade. Among the most heinous of these executions, four hundred Cathar Perfects were burned at Lavaur in 1211.

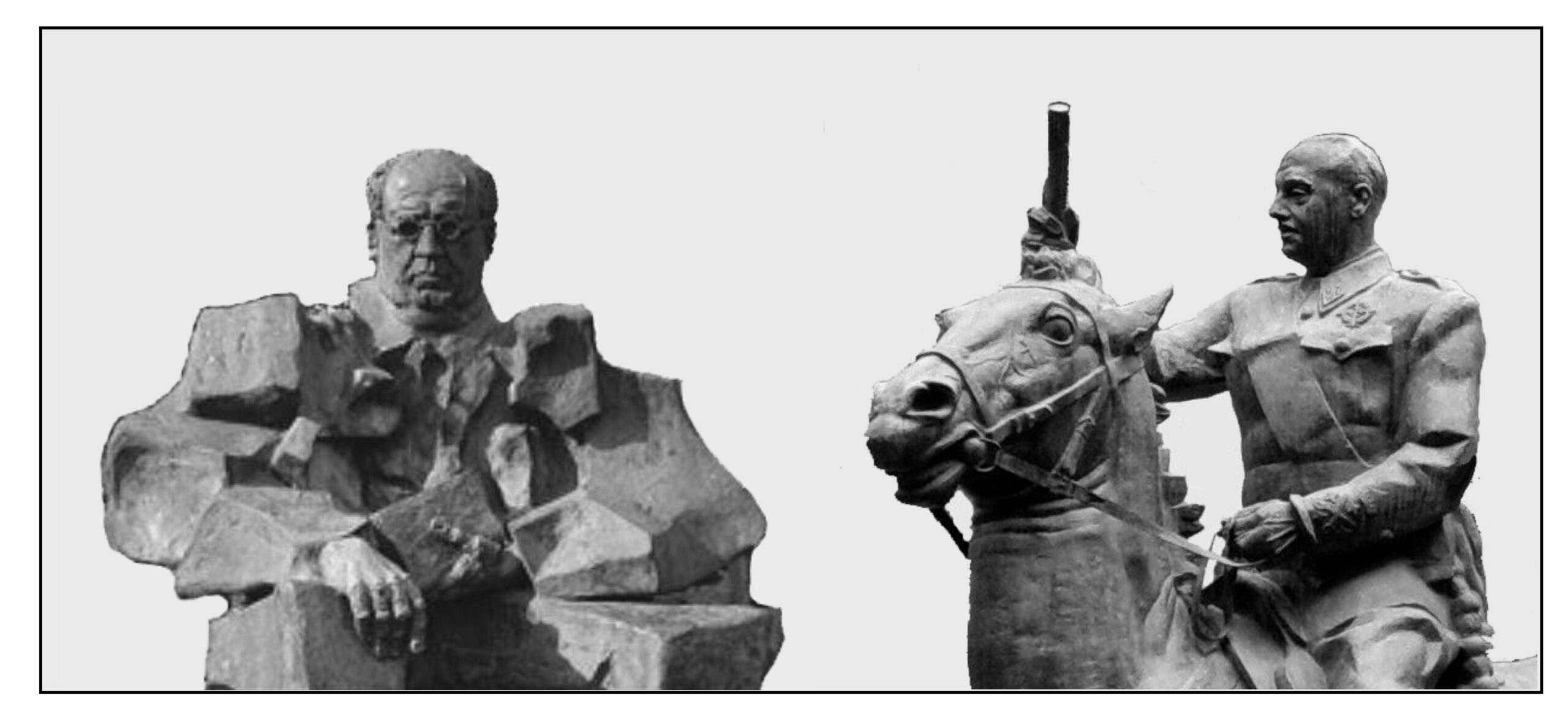

The Battle of Muret

Simon de Montfort continued to take various towns and cities in Languedoc, but stayed away from Toulouse, which was large and well defended. Raymond VI of Toulouse negotiated support from Pedro II of Aragon and from Raymond-Roger of Foix and in 1213 a large army assembled on the plain outside the city walls of Muret just south of Toulouse, where the forces of Simon de Montfort were garrisoned. The crusaders were vastly outnumbered. Some reported a ratio of 10 to 1 although it was more likely 3 to 1.

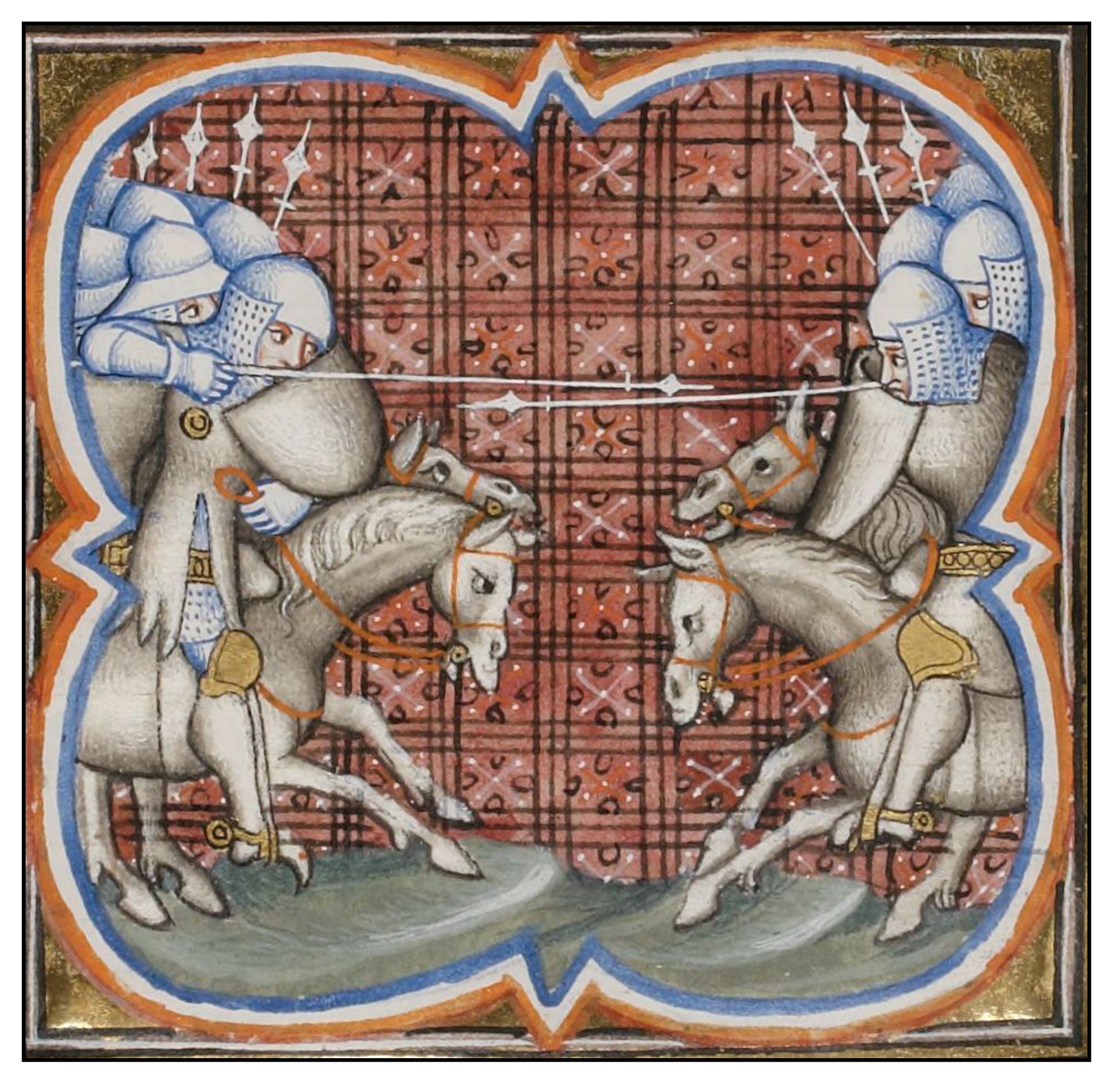

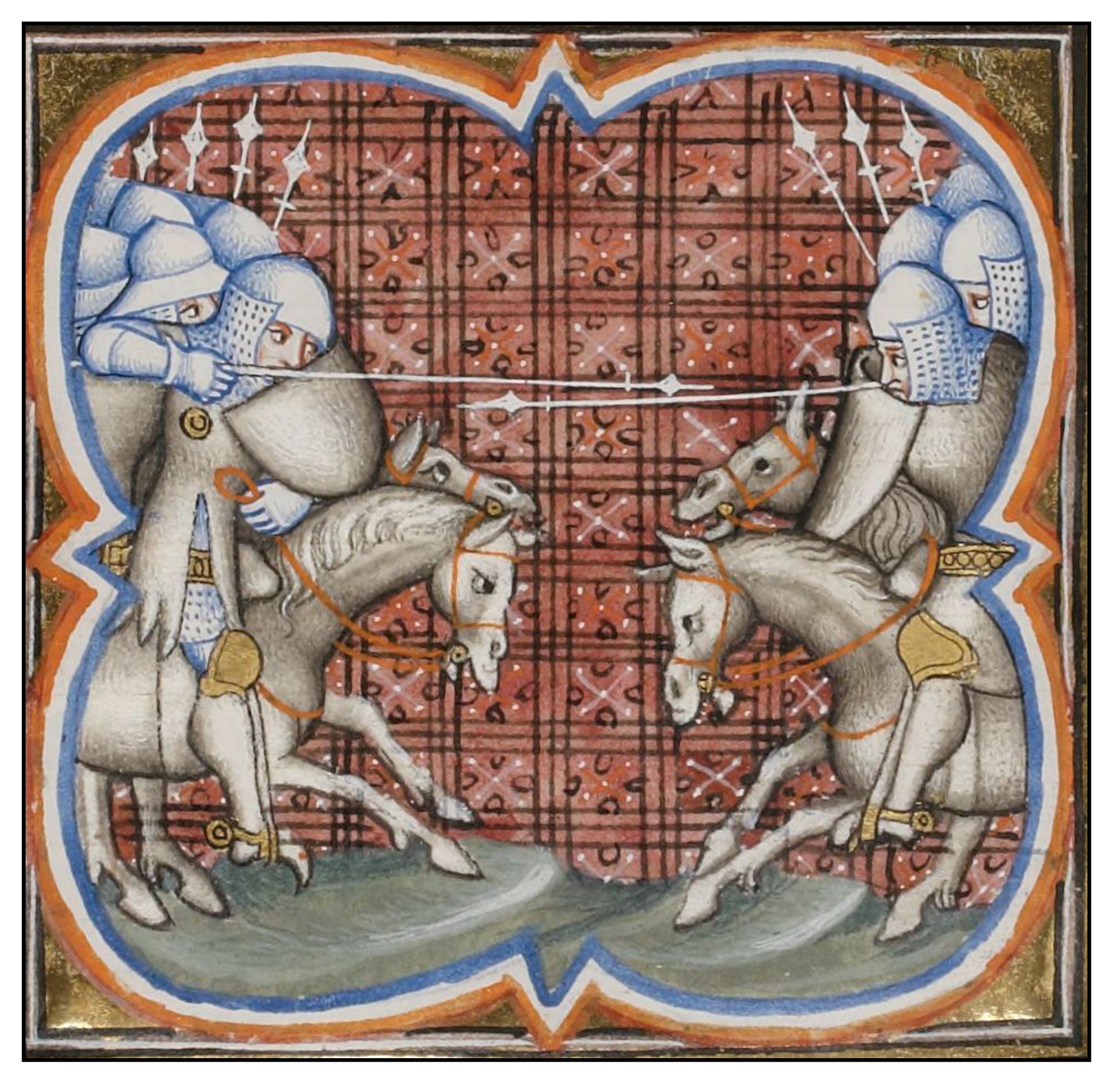

Early in the morning of September 12, 1213, Simon de Montfort said his prayers and led his knights out along the Garonne River away from the encampment of the besiegers. After a while he turned and led a ferocious charge against the besiegers (see illustration on the right from Les Grandes chroniques de France). The southerners turned toward them but the knights of the Crusaders hit the besiegers at full speed shattering their defenses and breaking through their lines (O’Shea, 2000, pp 141-149). The result was a complete rout. Among the thousands of Toulousian and Aragonese dead was Pedro II. Less than one hundred Crusaders died.

Toulouse

Toulouse remained unconquered. In 1215, the Pope convened the Fourth Lateran Council to broker disputes within the Christian lands. Raymond VI journeyed to Rome to plead the case for an independent Toulouse, but the council ultimately granted Simon de Montfort dominion over all of Languedoc. The crusaders, recently reinforced by prince Louis of France (later to become King Louis VIII), came to take up residence in Toulouse. In 1216, Raymond VI returned to regain his patrimony. Over the next two years the city changed hands several times.

On June 25, 1218, Simon de Montfort coming to the aid of his brother Guy who had been wounded in an assault on the city walls, was struck by a boulder launched by a catapult from within the city walls (illustration on the right from a 19th-Century engraving):

This was worked by noblewomen, by little girls and men’s wives, and now a stone arrived just where it was needed and struck Count Simon on his steel helmet, shattering his eyes, brains back teeth, forehead and jaw. Bleeding and black the count dropped dead on the ground (Shirley 2016, p 172)

The poet who wrote the latter parts of the Canso de la Crozada (Shirley, 2016) did not grieve the death of Simon. He reported that the crusaders took Simon’s body to Carcassonne for burial, and imagined a fitting epitaph. The original version in Occitan gives a flavor of the rhyming of troubadour poetry:

Tot dreit a Carcassona l’en portan sebelhir

El moster S. Nazari celebrar et ufrir,

E ditz el epictafi, cel quil sab ben legir :

Qu’el es sans ez es martirs, e que deu resperir,

E dins el gaug mirable heretar e florir,

E portar la corona e el regne sezir;

Ez ieu ai auzit dire c’aisis deu avenir:

Si per homes aucirre ni per sanc espandir,

Ni per esperitz perdre ni per mortz cosentir,

E per mals cosselhs creire, e per focs abrandir,

E per baros destruire, e per Paratge aunir,

E per las terras toldre, e per orgolh suffrir,

E per los mals escendre, e pel[s] bes escantir,

E per donas aucirre e per efans delir,

Pot hom en aquest segle Jhesu Crist comquerir,

El deu portar corona e el cel resplandir!

[Straight to Carcassonne they carried it and buried it with masses and offerings in the church of St Nazaire. The epitaph says, for those who can read it, that he is a saint and martyr who shall breathe again and shall in wondrous joy inherit and flourish, shall wear a crown and be seated in the kingdom. And I have heard it said that this must be so – if by killing men and shedding blood, by damning souls and causing deaths, by trusting evil counsels, by setting fires, destroying men, dishonouring paratge, seizing lands and encouraging pride, by kindling evil and quenching good, by killing women and slaughtering children, a man can in this world win Jesus Christ, certainly Count Simon wears a crown and shines in heaven above. (Shirley, 2016, laisse 208)]

The word paratge in Occitan is difficult to translate. It derives from the Latin par (equal) and is thus similar to the English word “peerage.” However, it had come to mean all that was good in Occitan society: equality, honor, chivalry, hospitality, joie de vivre.

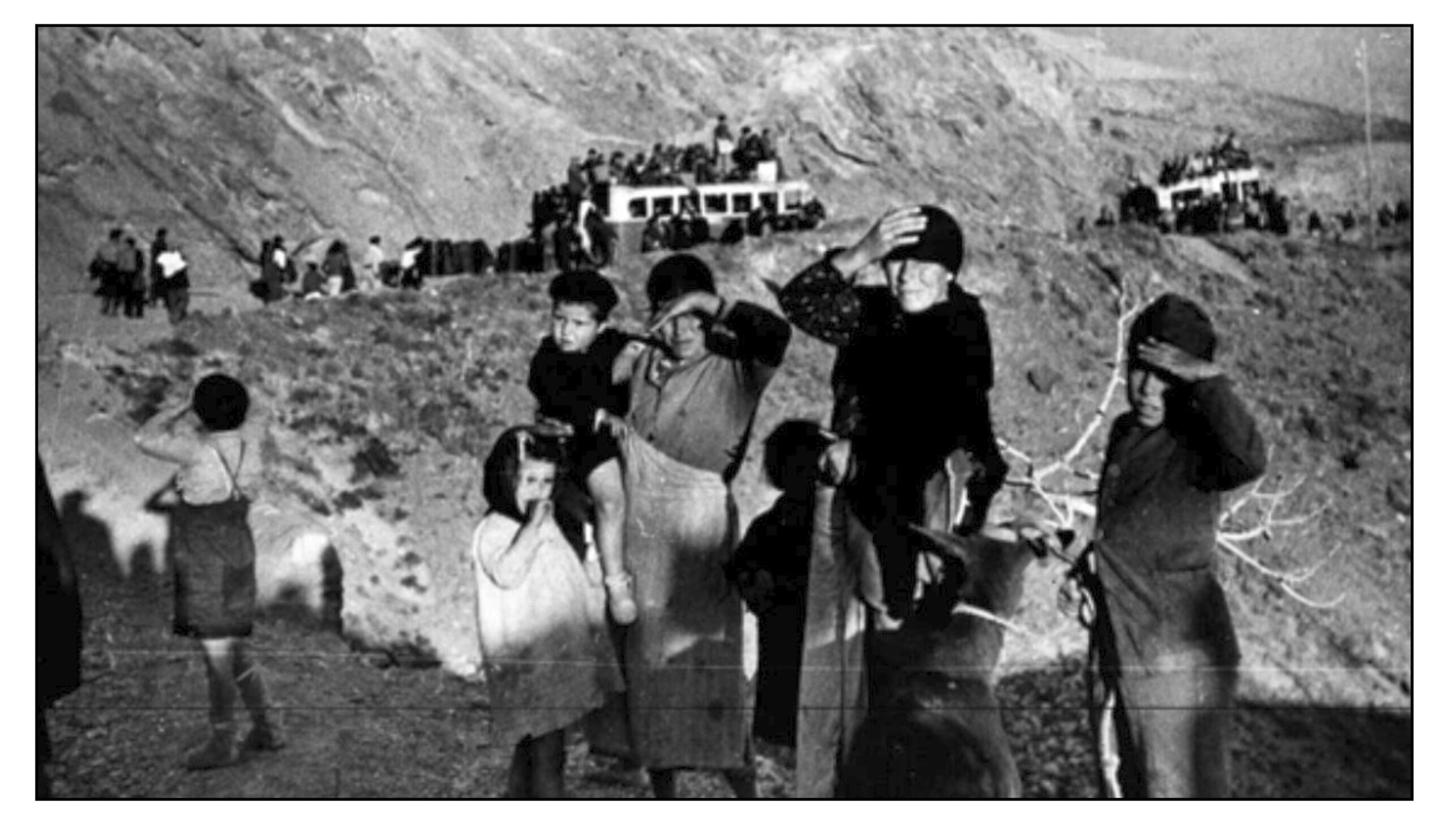

The End of the Crusade

After the death of Simon de Montfort, the crusade continued intermittently. Various strongholds in the domain of Toulouse were conquered by the crusaders. Louis VIII of France became the main leader of the crusade. He conquered the city of Marmande in 1219 but was unable to take Toulouse. Many of the Cathars retreated to mountain strongholds. Raymond VI died in 1222; Raymond-Roger of Foix died in 1223. Their heirs lacked their strength and charisma. Most historians date the end of the Crusade to 1229 when the Treaty of Paris was signed in Meaux, granting the Kingdom of France dominion over all the lands previously held by Toulouse.

In order to root out the remaining Cathars in Languedoc, Pope Gregory IX established the Papal Inquisition in 1231. Instead of allowing local bishops investigate heretics, the pope appointed itinerant inquisitors from among the ranks of the Dominicans and the Franciscans. Accompanied by clerks and lawyers, these inquisitors travelled throughout the region of Languedoc, seeking out heretics, bringing them to trial, and handing them over to the secular authorities for burning (Deane, 2011, Chapter 3) For their faithful service the Dominicans became known as the Dogs of God (Domini canes).

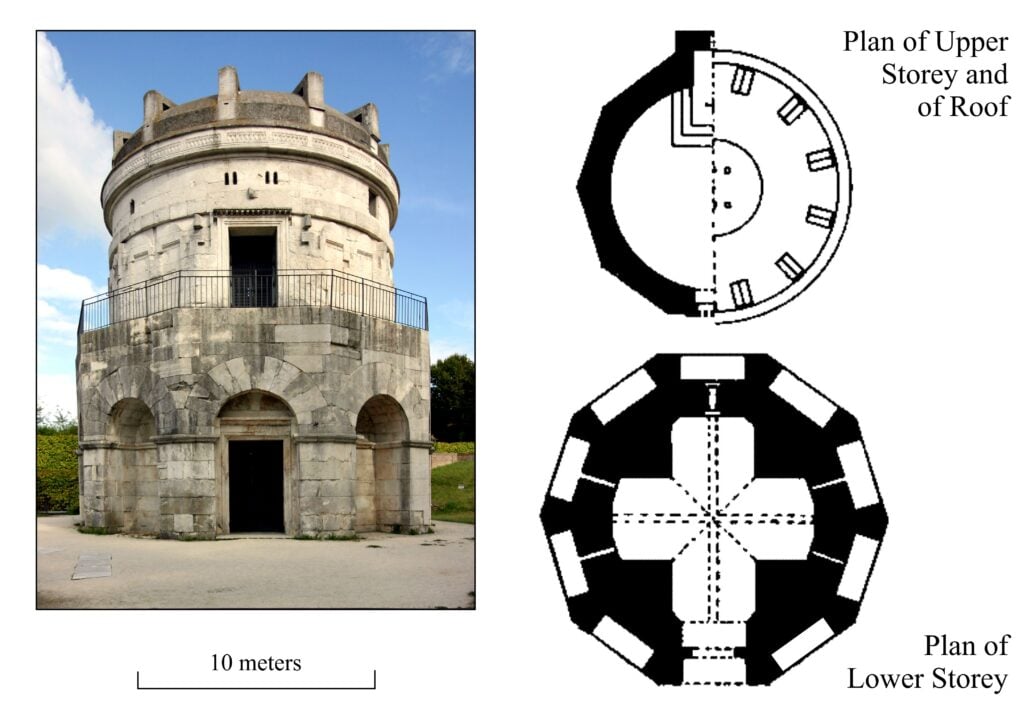

One of the last Cathar refuges to fall was Montségur (Occitan for “safe hill”) a castle built on top of a steep and isolated peak known in Occitan as a puog (illustrated below). The castle was 170 m above the plain and the stronghold was virtually impregnable. In 1242 two inquisitors were murdered by Cathars from Montségur. The French forces (now under Louis IX) began the siege of the isolated mountain stronghold in May 1243. Slowly and inexorably the French came closer to city until it was within range of their catapults. The castle finally surrendered in March 1244. About 220 Cathar Perfects were burned to death on the field below the puog. This became known as the Plat dels Cremats (field of the burned).

Saint Peter Martyr

The Inquisition moved on from Languedoc to the Northern Italy. In 1852, Peter of Verona, a Dominican friar, was appointed Inquisitor in Lombardy. When returning from Como to Milan, Peter and his companion Domenic were assassinated by assassins hired by the Milanese Cathars. This is illustrated in a 1507 painting by Giovanni Bellini (see below). Despite the foreground violence one can see in the distance a countryside of peace and beauty. The woodsmen go about their work. The light from the harvest shines through the trees.

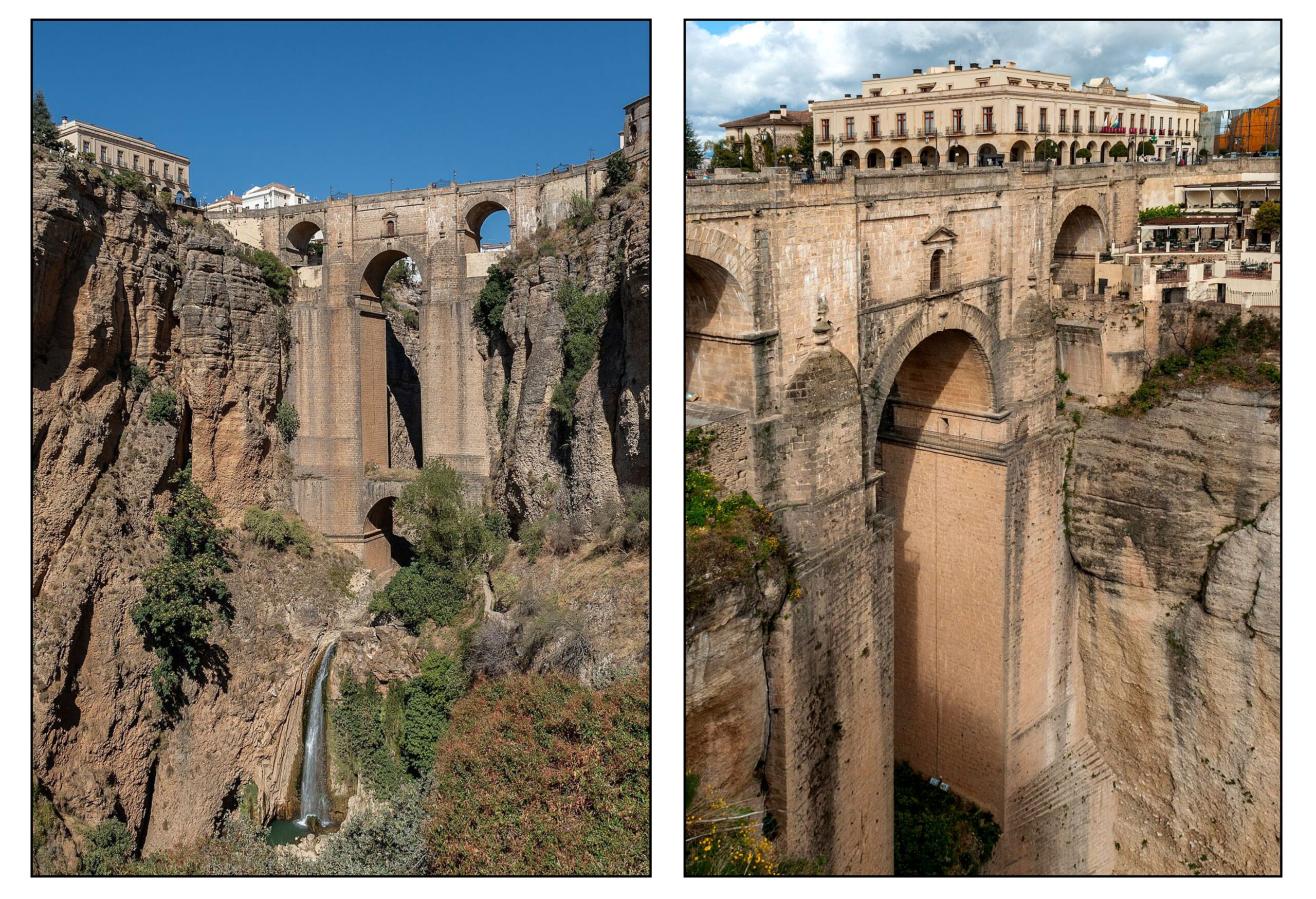

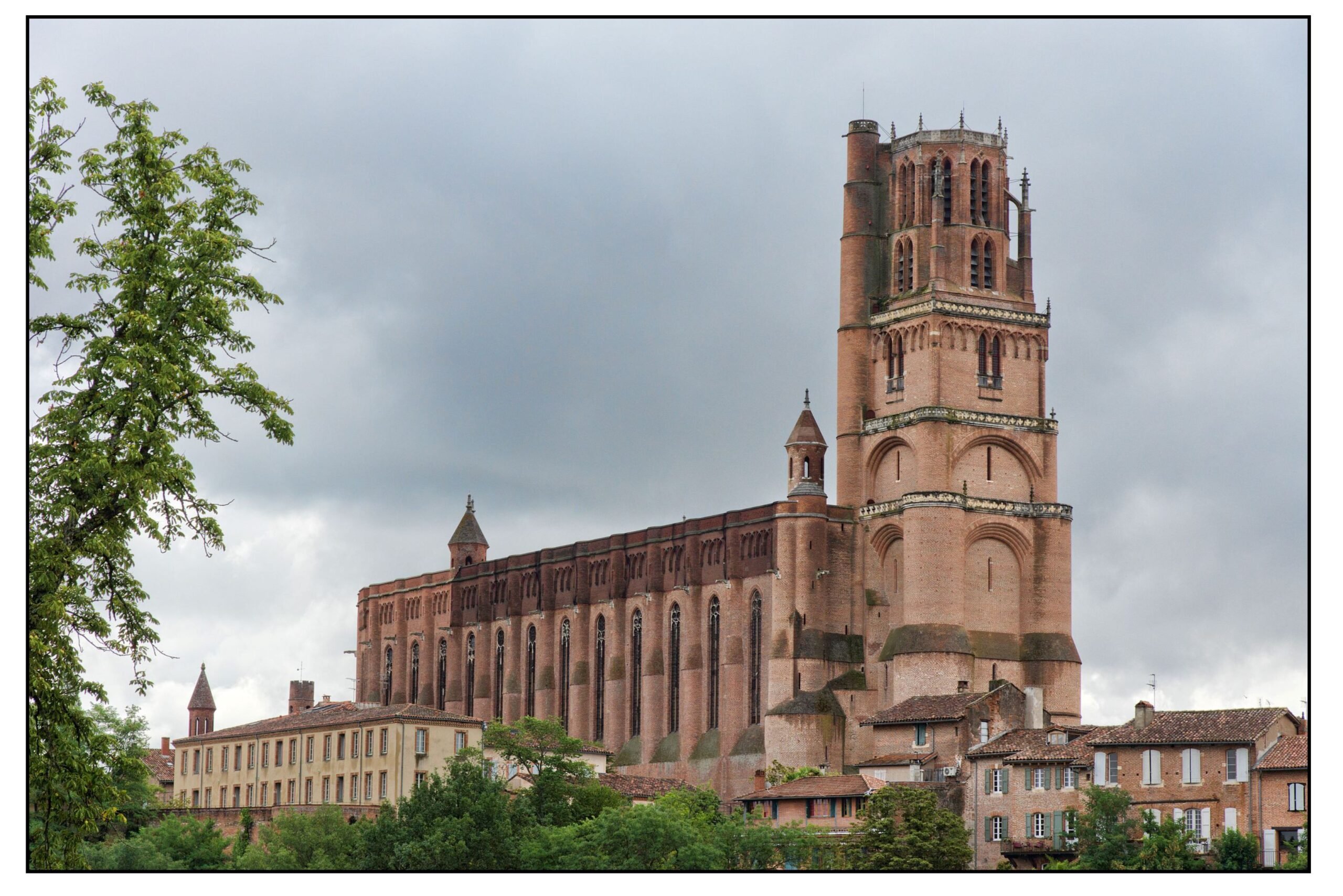

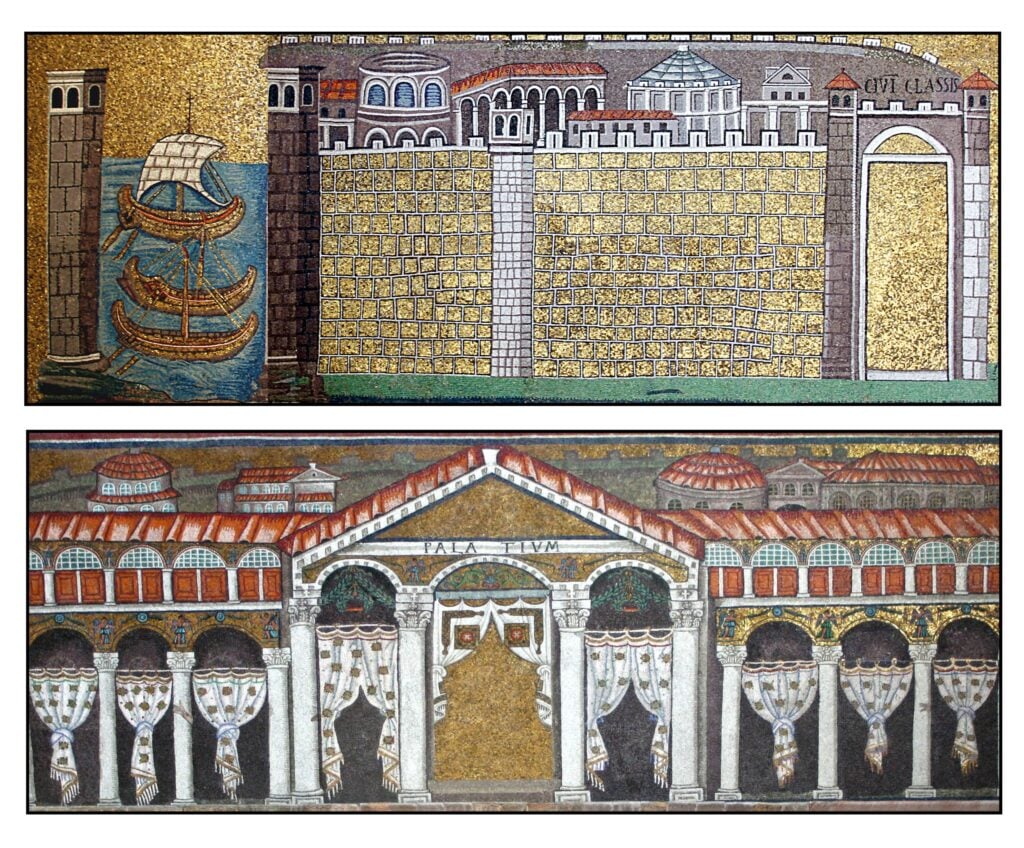

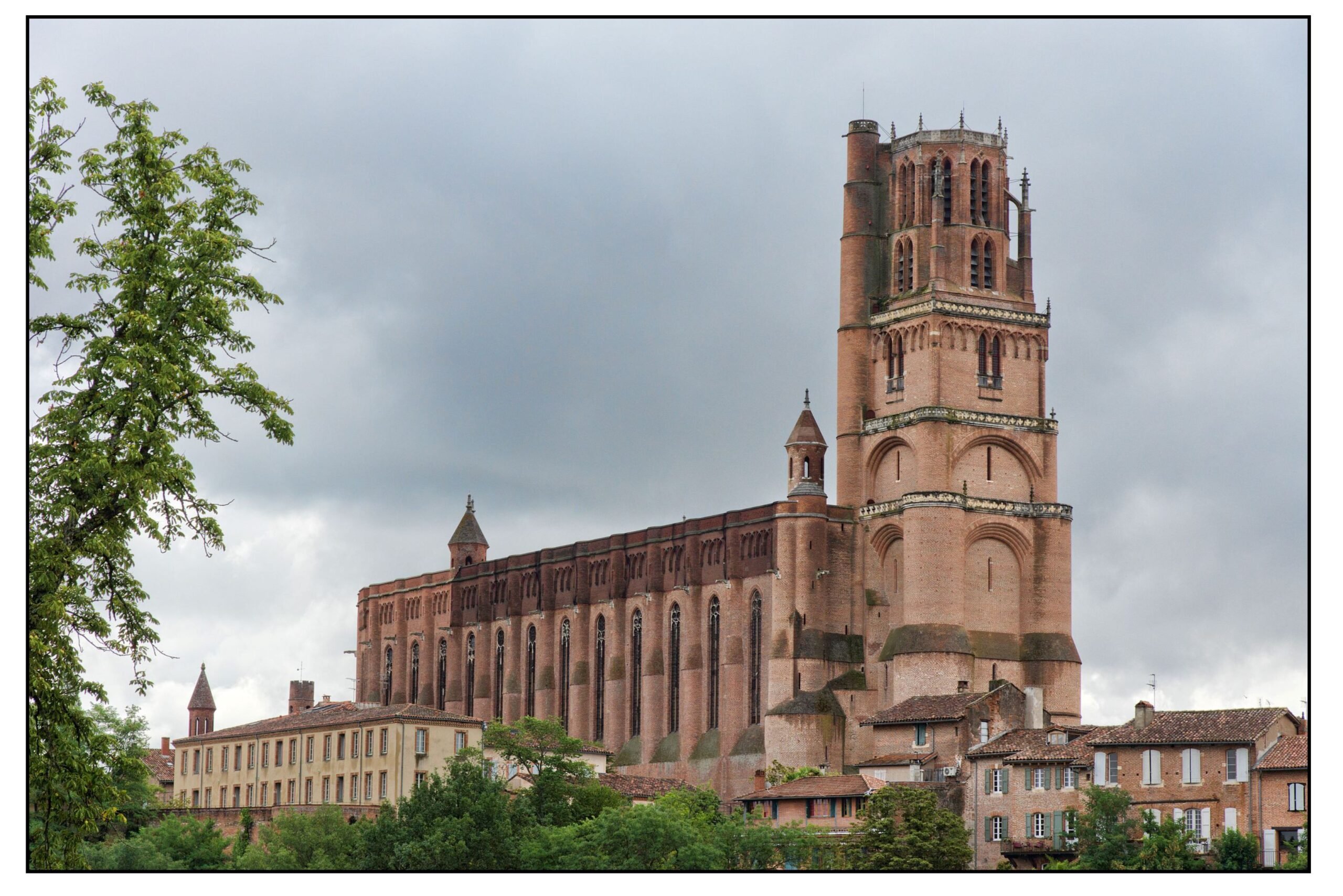

Albi

In 1282 work was begun on the new Cathedral Basilica of Saint Cecilia in Albi, which was to become the largest brick building in the world. With its narrow windows and huge tower, it dominates the city like a fortress, a true bastion against heresy (see below). Above the high altar a vast fresco of the Last Judgement reminds the people of Languedoc of the torments that await those that do not follow the true teachings.

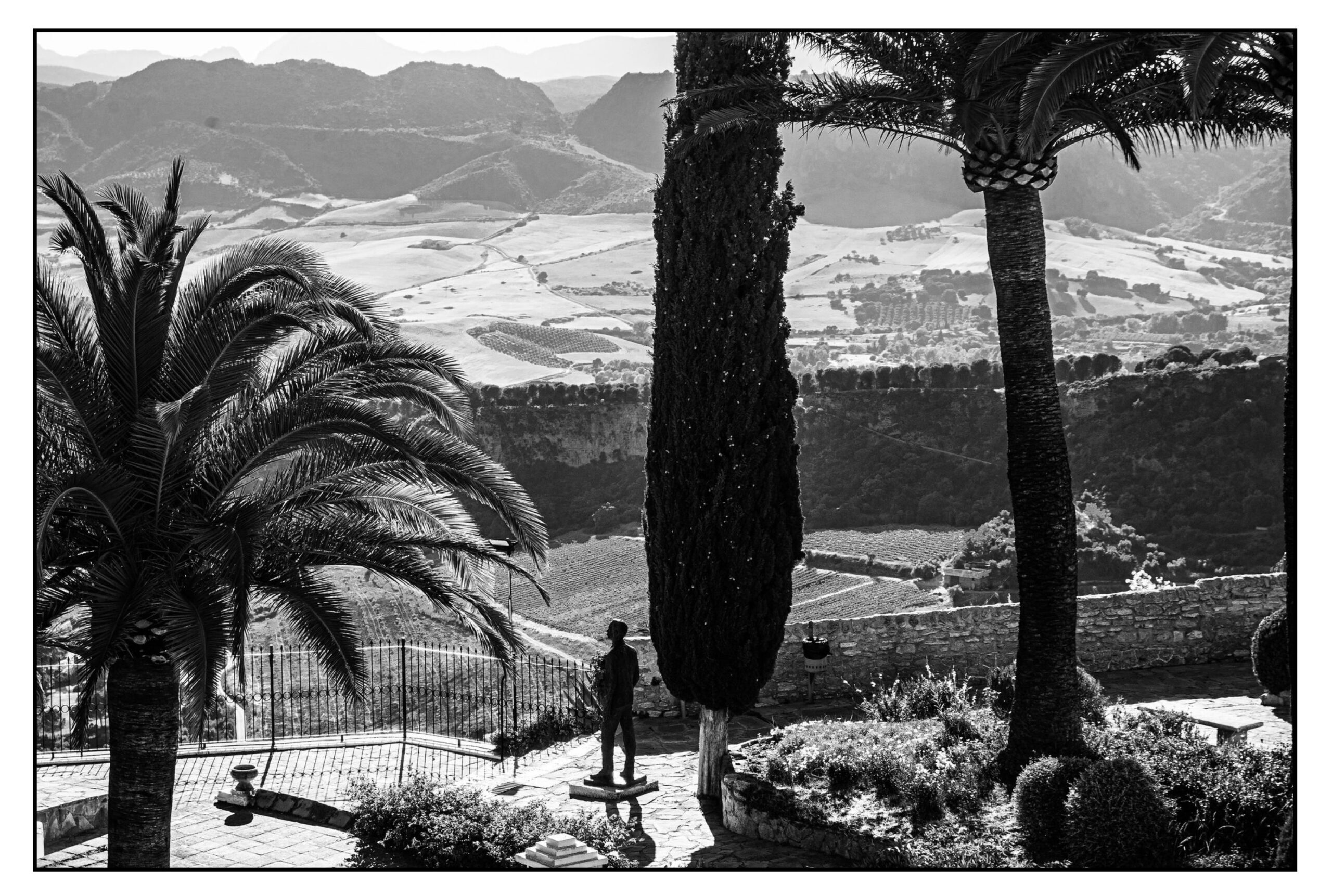

Peyrepertuse

The history of the Cathars should not end with the formidable Cathedral of Albi. More fitting is the Cathar castle of Peyrepertuse (from Occitan pèirapertusa, pierced rock). It was finally surrendered to the French in 1240, and later became part of the French border defences.

References

Barbezat, M. D. (2014) The fires of hell and the burning of heretics in the accounts of the executions at Orleans in 1022. Journal of Medieval History, 40(4), 399-420,

Barbezat, M. D. (2018). Burning Bodies: Communities, Eschatology, and the Punishment of Heresy in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Pres

Boboc, R. (2009). Kabbalists, Cathars and Ismailis: Forms of Gnosis in the 11th–13th Century. Studia Hebraica, 9-10, 267–293.

Chaytor, H. J. (1912). The troubadours. Cambridge University Press.

Deane, J. K. (2022). A history of medieval heresy and inquisition. Rowman & Littlefield.

Frassetto, M. (Ed.) (2006). Heresy and the Persecuting Society in the Middle Ages: Essays on the Work of R. I. Moore. Brill.

Frassetto, M. (2008). The great medieval heretics: five centuries of religious dissent. BlueBridge.

Hamilton, B. (2006). Bogomil influences on Western heresy. In Frassetto, M. (ed.) Heresy and the Persecuting Society in the Middle Ages: Essays on the Work of R. I. Moore. (pp 93-114) Brill.

Leglu, C., Rist, R., & Taylor, C. (2014). The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade: a sourcebook. Routledge.

Mabillon, J., & Eales, S.J. (1896) Collected works of Bernard of Clairvaux. Volume IV. Cantica canticorum. Eighty-six sermons on the Song of Songs. John Hodges

Marvin, L. W. (2008). The Occitan War: a military and political history of the Albigensian Crusade, 1209-1218. Cambridge University Press.

McDonald, J. (2017). Cathars and Cathar Beliefs in the Languedoc (Informative website).

Moore, R. I. (1985). The origins of European dissent. Blackwell.

Moore, R. I. (1987, revised 2007). The formation of a persecuting society authority and deviance in Western Europe, 950-1250. Blackwell.

Moore, R. I. (2012). The war on heresy. Belknap Press

Oldenbourg, Z. (1959, translated by P. Green, 1961). Massacre at Montségur: a history of the Albigensian Crusade. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

O’Shea, S. (2000). The perfect heresy: the revolutionary life and death of the medieval Cathars. Walker

Paterson, L. M. (1993). The world of the troubadours: medieval Occitan society, c. 1100-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press.

Pegg, M. G. (2001). On Cathars, Albigenses, and good men of Languedoc. Journal of Medieval History, 27(2), 181–195.

Roquebert, M. (1999). Histoire des cathares: hérésie, croisade, Inquisition du XIe au XIVe siècle. Perrin.

Sennis, A. C. (Ed.) (2016). Cathars in question. York Medieval Press.

Shirley, J. (2016). The song of the Cathar wars: a history of the Albigensian Crusade. Routledge.

Sioen, G. & Roquebert, M. (2001). Cathares: la terre et les hommes. Place des Victoires.

Smith, A. P. (2015). The lost teachings of the Cathars: their beliefs and practices. Watkins.

Wakefield, W. L., & Evans, A. P. (1991). Heresies of the high Middle Ages. Columbia University Press.

Wakefield, W. L. (1974). Heresy, Crusade, and Inquisition in Southern France, 1100–1250. University of California Press