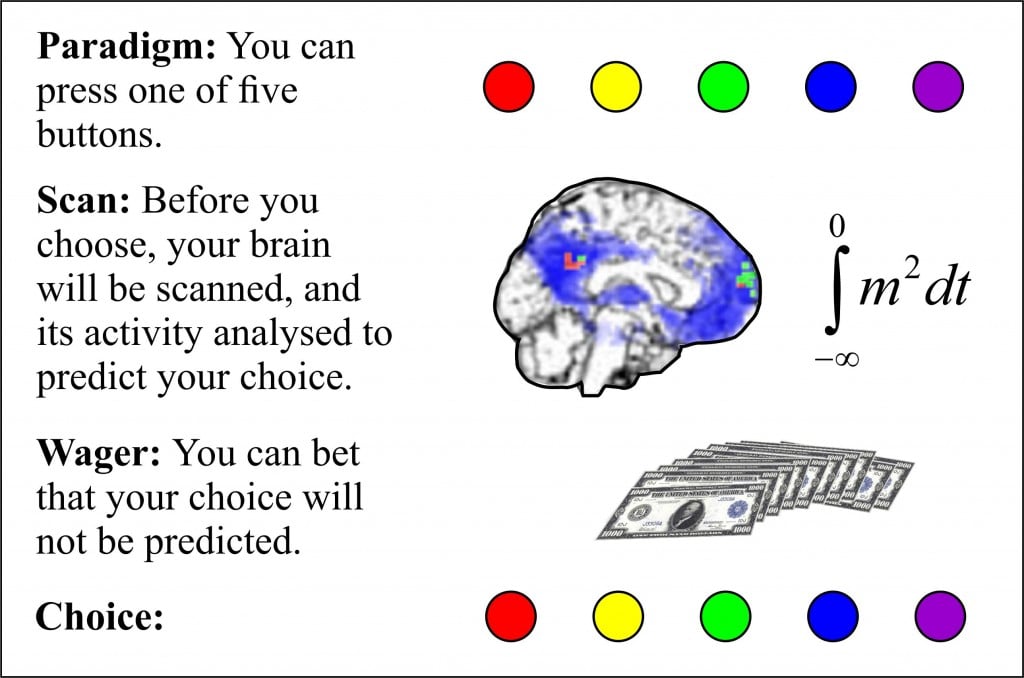

Scenario

Imagine yourself 20 years from now. A brilliant cognitive neuroscientist claims to be able to read your brain and predict your future behavior. She studied with Sam Harris in Los Angeles and then completed her postdoctoral work with Chun Siong Soon and John-Dylan Haynes in Berlin. She knows her stuff and she uses the most advanced technology.

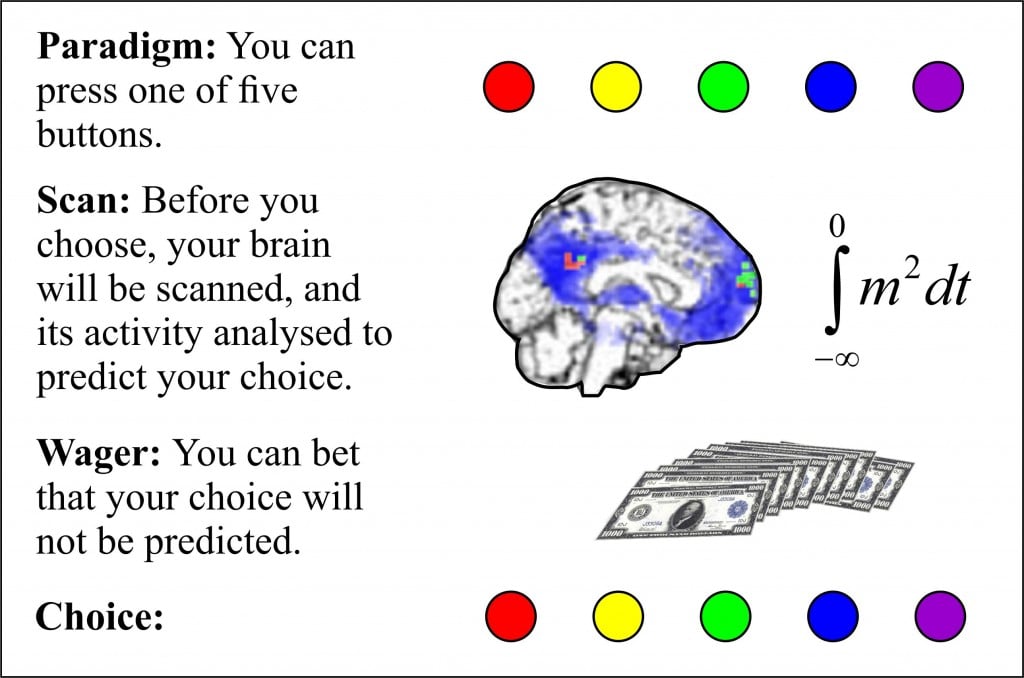

You will be able to press one of five buttons. Before you do so, the neuroscientist will take a scan of your brain, analyse it and predict which button you will choose. She will pay particular attention to the posterior cingulate gyrus and the rostral prefrontal cortex. She is willing to bet you that her prediction will be correct.

If you take the bet, you believe in free will. If you do not, you are a determinist – or in this context a “neuro-determinist.”

Faites vos jeux!

Concept of Determinism

Modern determinism was most clearly stated by Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1812. He proposed that an intelligence – whether God or Demon, whether real or hypothetical – could completely predict the future from the present if the intelligence knew all the “forces by which nature is animated” and could measure the exact “situation” of everything in the present universe:

We ought then to regard the present state of the universe as the effect of its anterior state and as the cause of the one which is to follow. Given for one instant an intelligence which could comprehend all the forces by which nature is animated and the respective situation of the beings who compose it – an intelligence sufficiently vast to submit these data to analysis – it would embrace in the same formula the movements of the greatest bodies of the universe and those of the lightest atom; for it, nothing would be uncertain and the future, as the past, would be present to its eyes (Laplace, 1812/1902, p 4).

Determinism is the basic premise of science, which attempts to discern the causal laws by which the universe operates (Earman, 1986; Hoefer, 2010). Everything is caused by something else. Nothing is a causa sui (cause of itself). The universe contains no freely acting anything or anybody.

Determinism is usually interpreted in terms of what will happen. However, in Laplace’s definition it also casts its net backward: if we know everything about the present then we can tell exactly what happened in the past.

What is not always recognized is that Laplace wrote his definition of determinism in the introduction to his book A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities. Now, probability is what we use when we cannot predict exactly what will happen. A hypothetical vast intelligence might, but we cannot. We estimate the odds rather than predict the outcomes.

If the concept of determinism is taken seriously, then the present is determined by the immediate past, that past is itself determined by what preceded it, and so on. Ultimately, everything must have been decided when the world began, and all our actions determined 13.8 billion years ago at the moment of the Big Bang. In the words of Omar Khayyam:

With earthʹs first clay they did the last man knead,

And there of the last harvest sowed the seed.

And the first morning of creation wrote

What the last dawn of reckoning shall read.

(Fitzgerald translation, 5th Version LXVIII)

Determinism is a powerful working hypothesis but it may not be universally applicable. In the early 20th century, we became aware that atomic and sub-atomic processes are not deterministic (Ismael, 2015). They follow exact rules, but these are expressed in terms of probabilities rather than certainties.

Most biologists consider that at the levels of chemistry and physiology, quantum uncertainty averages out and we are “for all intents and purposes” fully determined. At macroscopic levels, quantum uncertainty therefore plays no significant role in the prediction of the future.

My suggestion, however, is that the universe veers away from strict determinism both at levels of extreme simplicity – quantum uncertainty – and at levels of extreme complexity – conscious choice.

Problem of Chaos

Sometimes, as Edward Lorenz (1996) has shown, fully determined systems are liable to chaos. Chaos occurs “when the present completely determines the future, but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future” (Lorenz, 2005).

The movie below provides an example of a typical deterministic system – billiard balls on a billiard table. If the rules by which the system operates and the positions and velocities of the balls are exactly known, the future of the system can be precisely predicted. The life of a billiard ball goes from collision to collision. Although there are occasional near misses there is no choice.

On the left is the actual system. It is not perfect – the table is frictionless and the balls are inelastic (there is only so much an old man can program) – but it does follow deterministic laws. On the right is the modeled system. If we initiate movement in the white ball, our prediction fits exactly with what happens.

Please enable JavaScript

.fp-color-play{opacity:0.65;}.controlbutton{fill:#fff;}

play-sharp-fill

Some determined systems, however, are chaotic. In a chaotic system our predictions can be wildly off the mark if our measurement of the initial state of the system is not exact. Chaos is usually considered in terms of complex systems such as the weather: butterflies in Brazil causing tornados in Texas. However, chaos also occurs in very simple systems, even in billiards.

The next example shows the same deterministic system on the left as in the previous movie. On the right is the prediction. This time the measurement of the initial position of the white ball was out by one pixel. The measurement of the velocity vector was exact.

At the very beginning the prediction is approximately correct. After the first few seconds, however, the model shows no relationship whatsoever to the actual.

Please enable JavaScript

.fp-color-play{opacity:0.65;}.controlbutton{fill:#fff;}

play-sharp-fill

Chaos is an inherent part of physical determinism. It is therefore often impossible to measure the state of the world with sufficient accuracy to give any meaningful predictions of what will actually occur. Our model of the future may look nothing like what it will be.

Chaos does not disprove determinism: chaos is completely determined. However it makes it very difficult to prove that determinism underlies everything. That hypothesis would require that we be able to measure the universe with absolute accuracy. That we cannot do.

Limits of Prediction

Even without chaos, complete predictability is impossible. The universe contains neither time nor space enough to map its own future.

Laplace was wrong to claim that even in a classical, non-chaotic universe the future can be unerringly predicted, given sufficient knowledge of the present. (Wolpert, 2008).

The proof is related to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem and Turing’s Halting Problem. A Turing machine reads an infinite tape one symbol at a time. According to its internal state at the time of reading, the machine then changes the symbol written on the tape, moves the tape, and changes its state. The Turing machine is a model of a computer. We cannot predict when the machine will stop. We are unable to know if a problem is soluble before it is solved. We cannot predict the entire future before it has already occurred.

The proof is related to Gödel’s Incompleteness Theorem and Turing’s Halting Problem. A Turing machine reads an infinite tape one symbol at a time. According to its internal state at the time of reading, the machine then changes the symbol written on the tape, moves the tape, and changes its state. The Turing machine is a model of a computer. We cannot predict when the machine will stop. We are unable to know if a problem is soluble before it is solved. We cannot predict the entire future before it has already occurred.

David Wolpert’s work means that “No matter what laws of physics govern a universe, there are inevitably facts about the universe that its inhabitants cannot learn by experiment or predict with a computation.” (Collins, 2009). The most we can hope for is a “theory of almost everything” (Binder, 2008).

However, even though we cannot prove determinism, we cannot disprove it. It continues to be a reasonable working hypothesis for most situations.

Lack of predictability is a characteristic of free will. A test for free will (Lloyd, 2012) might involve the following criteria: the ability to make decisions, the use of recursive reasoning in making those decisions, the ability to predict the future, and the inability to predict what one will decide. If you are in the process of deciding how to act and if you cannot predict how you will decide, you are in a state of free will.

Quantum Uncertainties

One way out of the problem that quantum uncertainty poses for determinism is to claim that yet-unknown deterministic laws underlie quantum events. Once we discover these laws we will be able to re-cast quantum mechanics so that all events are exactly rather than stochastically determined. The problem with such a “superdeterminism” is that in order to derive the underlying laws governing quantal processes we would have to observe events at subquantal levels. That would require using subquantal measuring devices, and that would run up against Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle (Hilgevoord & Uffink, 2006). I think indeterminism is here to stay. The only thing we can be certain about is ultimate uncertainty.

Quantum uncertainty may provide a way for our behavior not to be fully determined by antecedent causes. We would need to imagine some way for unpredictable quantum events to change brain activity. Penrose and Hameroff (2011) have suggested that quantum events in the neuronal microtubules – the Orchestrated Objective Reduction of Quantum States – could underlie our choices of one action over another.

However, making free will depend on quantum uncertainty is unsatisfying in that it reduces free will to chance rather than choice. Random is not the same as free. If we make our decisions on the basis of random quantum events, we are just subject to the tyranny of the atom rather than the will of God.

Even Sam Harris agrees:

Chance occurrences are by definition ones for which I can claim no responsibility. And if certain of my behaviors are truly the result of chance, they should be surprising even to me (Harris, 2012).

However, randomness can still play a role in free choice. We might decide to base our decisions on a random event, such as flipping a coin, so as to be fair to both sides of a question. We might also use a random process to add noise to a decision (like raising the temperature in an annealing process), or to determine how many options to evaluate or for how long (e.g. Dennett, 1978). For Peter Tse (2013) free will is caused by the “criterial selection” of random synaptic activity in cerebral cortex.

Logical Problems

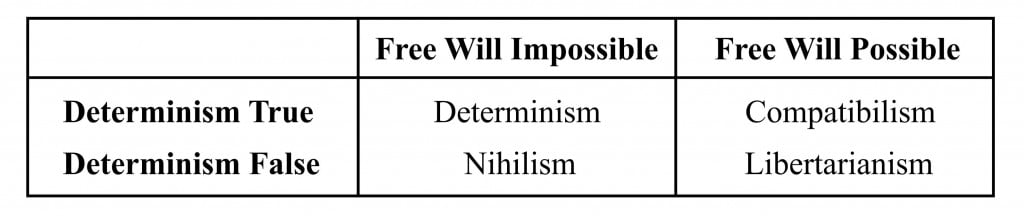

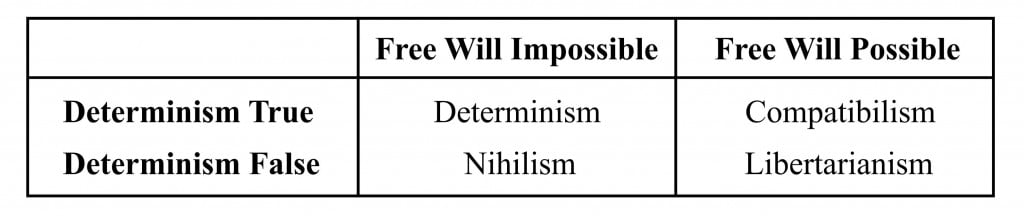

Two contradictory statements can be made in relation to free will and determinism (van Inwagen, 1983, 2008):

(i) Freedom of the will is not possible if the world is completely determined. Free will means that we are sometimes in the position with respect to a contemplated future act that we are able either to perform the act or to do otherwise. If we can indeed do otherwise – if two different futures can equally follow from the same present – then the future is not determined. The claim that we can choose between these two futures is incompatible with the idea that the past and the laws of nature together determine, at every moment, a unique future.

(ii) However, free will cannot act without determinism. If we make a decision, we can only carry it out if our behavior is determined by that decision – if action potentials travel down the nerves to the muscles, if the muscles move the limbs, and if the limbs perform the intended physical acts. Unless the world is deterministic, we cannot exercise our free will.

So we cannot have free will if the universe is completely determined, and free will is meaningless if the universe is not determined. There are two ways out of this conundrum. We can accept that the universe is determined, and conclude that our idea of free will is an illusion. Or we can agree with van Inwagen that free will is true and conclude that the world is not completely determined.

Van Inwagen considers free will to be true because he cannot imagine human life without personal moral responsibility. If there is no free will, everything we do is determined before we have anything to do with it. We need not think; we are never responsible for our actions; any idea of justice is meaningless. All evil will be exculpated by fMRI evidence that the brain was just unable to be good.

A world where people do not believe in free will is not pleasant. Simply suggesting to subjects that there is no free will encourages dishonesty and mischief. The less someone believes in free will, the more likely he or she will cheat if the opportunity presents (Vohs & Schooler, 2008), and the more likely she or he will indulge in anti-social acts if they will not be discovered (Baumeister et al., 2009).

So, even if we are not free, should we act as if we were? This is a strange way to live our lives.

However, we can take positions other that of full determinism in relation to the problem of free will:

Van Inwagen’s position is one of philosophical “libertarianism.” (This is not the same as political libertarianism, which disputes the laws of society rather than the laws of science.)

Most of us believe that we have free will, but we are also convinced that the universe is determined. We are “compatibilists” – determinism is true but so is free will. We do not know how the two co-occur, but somehow they must. In surveys of what we believe, compatibilists are in a clear majority: 75% of normal folk (Nahmias et al, 2005), and 80% of biologists (Graffin & Provine, 2007). Even 60% of philosophers, those that should not support logical contradictions, consider themselves compatibilists (Bourget & Chalmers, 2014). The other 40% are evenly divided between undecided, libertarians and determinists.

Dan Dennett is the most prominent of our present compatibilists. But he is unclear about exactly how free will can exist in a world of causes. Something to do with human knowledge and communication:

Our autonomy does not depend on anything like the miraculous suspension of causation but rather on the integrity of the processes of education and mutual sharing of knowledge. (Dennett, 2003).

Evolution and Free Will

Darwin thought that free will was a delusion. Since we are not conscious of the instincts that actually drive our actions, we only think that we freely choose. In fact we do not.

The general delusion about free will obvious – because man has power of action, & he can seldom analyse his motives (originally mostly instinctive, & therefore now great effort of reason to discover them: this is important explanation) he thinks they have none. (from Darwin’s Notebooks, about 1839, edited by Barrett et al., 1987, p 608; these notes are discussed in Wright, 1994, p. 350).

Evolution is often considered as part of a general determinism. Selection occurs according to hard and fast rules. Species that cannot survive to reproduce do not continue. Yet indeterminism rests at the very heart of Darwin’s theory. Evolution depends on two processes: the production of offspring with variable characteristics and the selection of those offspring that survive in a world of limited resources. The variation is largely a result of genetic mutations and these are caused by indeterministic quantum events.

Some people have likened cognitive processing to Darwinian evolution (e.g., Edelman, 1987). In evolution, various species are created and only the most adaptive are selected. In cognition, various possible actions are considered and only the most appropriate are selected.

A major problem is why evolution determined that consciousness and free will occur. Human beings are certainly the most successful of all earth’s species. This would suggest that consciousness and free will are highly adaptive traits that have been selected to facilitate our survival. Evolution is a deterministic process. Yet by selecting out the fittest, evolution has led to consciousness and free will. We have been determined to be free.

Neurodeterminism

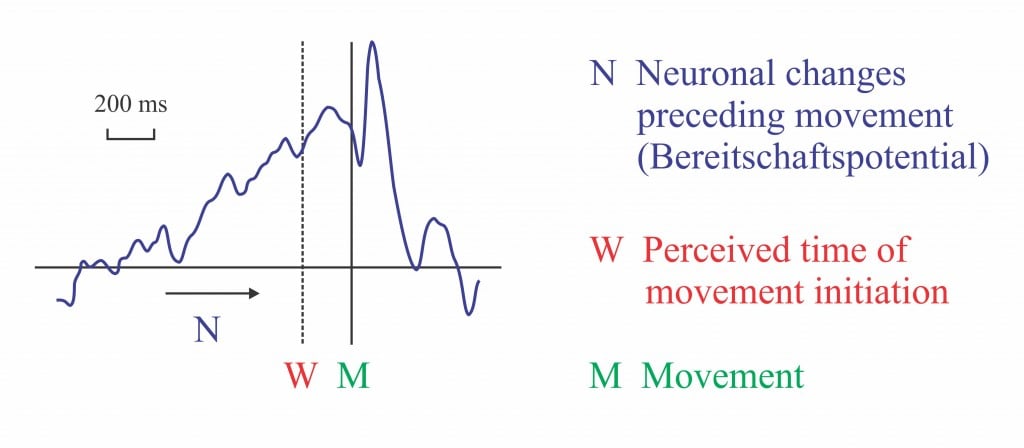

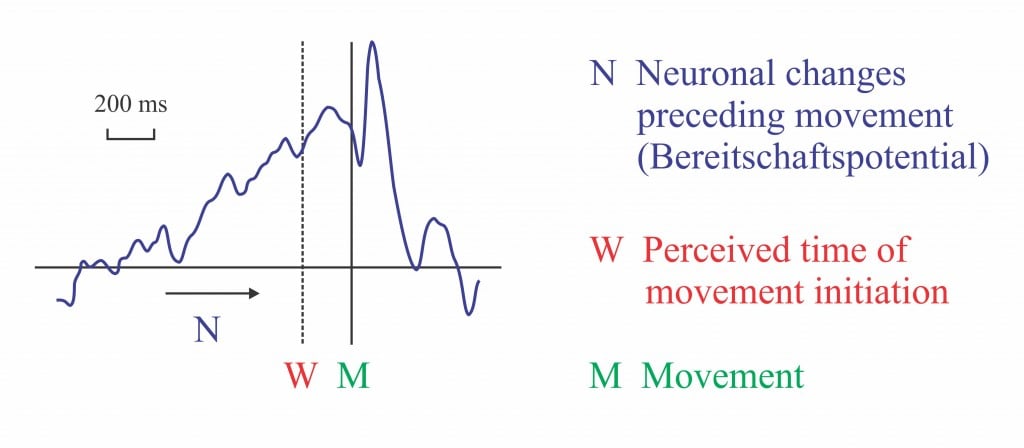

Neuroscience entered the philosophical arena in the early 1980s when Benjamin Libet evaluated the relations between volition and the readiness potential (or Bereitschaftspotential) recorded from the scalp. The readiness potential began up to a second before the movement but the subject consciously perceived the time of movement initiation at about 200 ms before the movement. The brain decides unconsciously; awareness follows after.

Similar experiments have recorded unit activity in the human frontal cortex beginning about 2 seconds before the act (Fried et al., 2011) and fMRI activation patterns (Soon et al., 2008, 2013) between 4 and 10 seconds prior to the act.

These experiments have led to a theory of volition that has been called “neuro-determinism.” Perhaps a better term might be “Libetarianism.” Our actions are willy-nilly determined by cerebral processes about which we are unaware. We only become conscious of what we are doing just before we do it. We do not control our actions, we just watch them taking place.

The 200 ms between the awareness of response-initiation and its occurrence could make it possible to inhibit or “veto” a response in process. Thus we can be consoled with the idea that even if we don’t have free will, we have “free won’t.” Yet recent experiments have shown that even this might be unconsciously driven (Filevich et al., 2013).

One problem with the neural measurements is that we do not know what they represent. Many different cerebral processes contribute to the readiness potential – estimating time, preparing to respond (or not), monitoring performance, etc. Some of these can be unconscious and can correlate significantly with later acts. Yet such processes do not necessarily cause the act – the mind can always change at the last minute (or millisecond).

In addition, our concept of volition is multidimensional (Roskies 2010). It can refer to the general intentions that one has in regard to a particular situation, the planning of how and when to respond, and the specific initiation of an act. A subject’s voluntary participation in a Bereitschaftspotential experiment involves his or her agreement to do what is asked by the experimenter, the setting up of the necessary timing and motor programs to control the responses, and the final initiation of the act. Any or all of these processes may contribute to the physiological recordings at different times.

Nevertheless, these physiological findings have led many scientists and philosophers to claim that our idea of free will is illusory:

Our sense of being a conscious agent who does things comes at a cost of being technically wrong all the time. The feeling of doing is how it seems, not what it is (Wegener, 2002).

Free will is an illusion. Our wills are simply not of our own making. Thoughts and intentions emerge from background causes of which we are unaware and over which we exert no conscious control. We do not have the freedom we think we have (Harris, 2012)

Farewell to the purpose-driven life. Whatever is in our brain driving our lives from cradle to grave, it is not purposes. But it does produce the powerful illusion of purposes (Rosenberg, 2011).

Eddy Nahmias (2015) has suggested that we call their position “willusionism.”

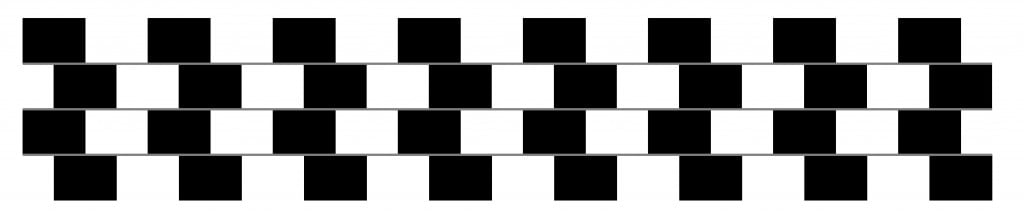

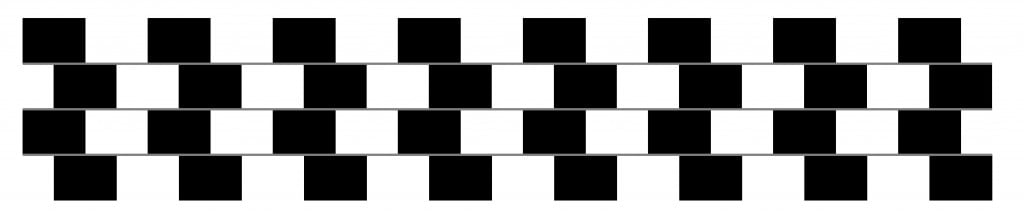

I submit that this idea is wrong – free will is not an illusion. Now, this is an illusion!

The argument that a particular experience is illusionary presupposes that other experiences are veridical. Indeed we only know that something is illusory if we can prove by some other experience that reality has been distorted. Despite the illusion of the tilting tiles in Richard Gregory’s café-wall, we can prove with a spirit level that they are actually all horizontal.

So in order to show that a particular experience of volition is illusionary, there would have to be other experiences of volition that are not illusionary and that are demonstrably different form the one considered illusionary.

Those who have proposed that free will is an illusion also point to clear evidence that we often do not know why we behave in a particular way. Psychoanalysis has long shown that we invent plausible but false reasons for how we act. This quotation is from Ernest Jones, one of Freud’s early disciples:

… the large majority of mental processes in a normal person arise from sources unsuspected by him. … No one will admit that he ever deliberately performed an irrational act, and any act that might appear so is immediately justified by distorting the mental processes concerned and providing a false explanation that has a plausible ring of rationality (Jones, 1908).

The psychoanalytic idea of rationalization has been supported by numerous recent psychological studies showing the effects of subliminal stimulation, the extent of our unconscious prejudices, and the vagaries of intuitions. We often are far more certain about things than we should be on the basis of the actual evidence (Burton, 2008).

Michael Gazzaniga’s studies of split-brain patients showed how the left hemisphere can invent totally inaccurate explanations for our actions. He suggests that the left-hemisphere language-system tries to make sense of our experience but that sometimes the story it comes up with is false:

It is the left hemisphere that engages in the human tendency to find order in chaos, that tries to fit everything into a story and put it into a context … even when it is sometimes detrimental to performance (Gazzaniga, 2011).

So perhaps we are always wrong? I think not. Just like the argument from illusion, the argument from rationalization only works if we are sometimes right. We have to know the real explanation in order to show that our rationalization is false.

Nature of Free Will

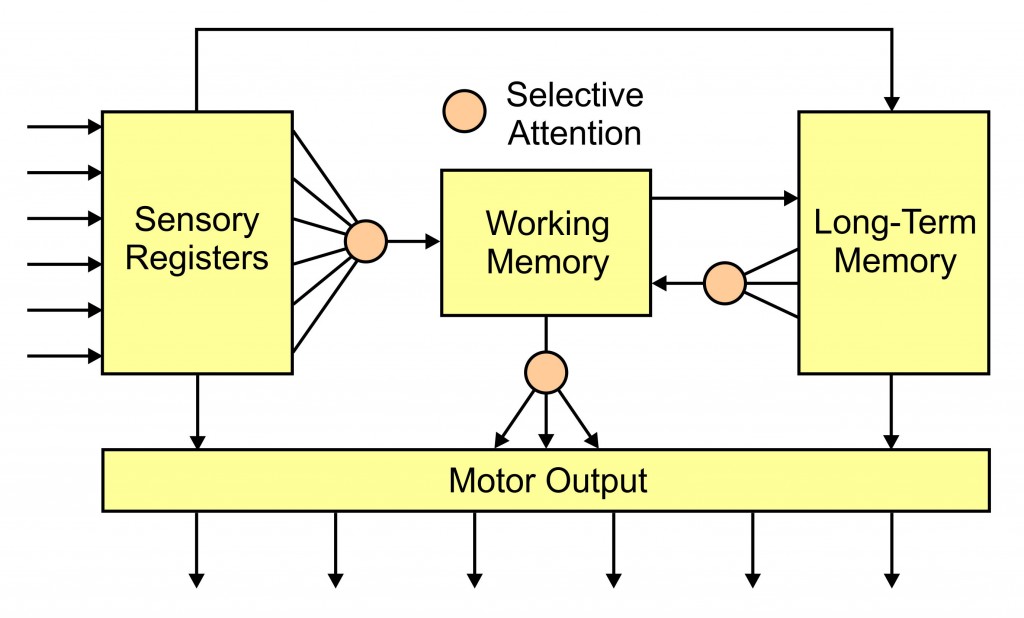

Only a small part of what we do is under conscious or controlled processing. Most of what we do occurs automatically. We are therefore often mistaken about why we acted in a particular way. We are not aware of causes outside of ourselves or hidden from conscious scrutiny, and we may invent reasons that are unrelated to what actually occurred, so that we can make sense of ourselves and our actions.

Nevertheless, we sometimes come to a decision about how to act by deliberately weighing the future consequences of several possible actions and choosing the most appropriate. We bring to bear on the problem all that we have so far learned about what things entail. For really important decisions, we often consult with others. We seek advice about what to do, ask our friends how they would decide in our position, and present scenarios for their comments. Freedom is inherently social. As mentioned above in relations to Dan Dennett’s compatibilism, free will has something to do with human knowledge and communication.

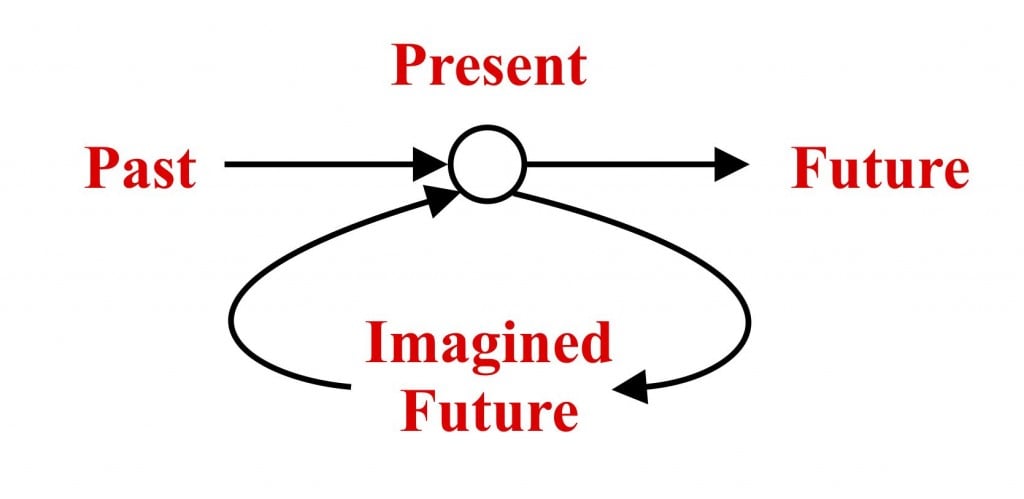

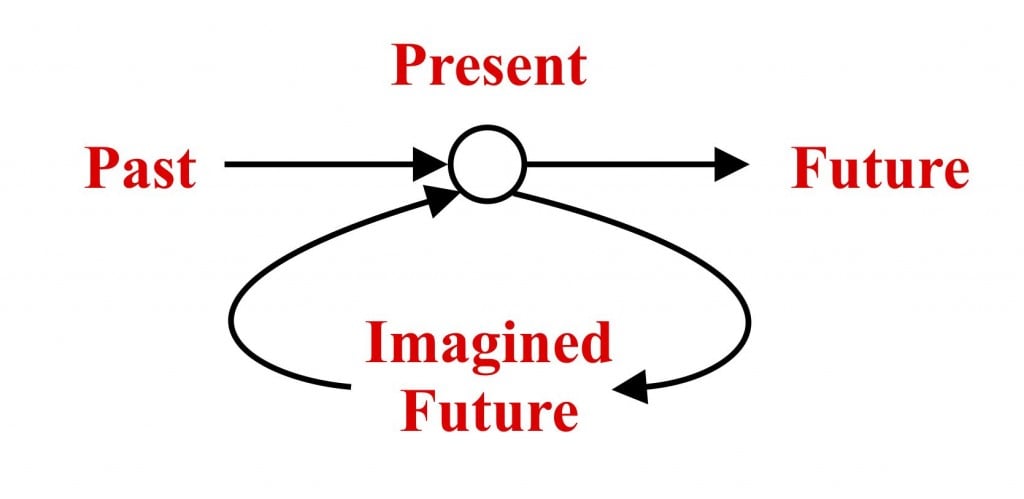

The future does not determine the present. That is not the way time flows. But the imagined future can determine the present. Once a feedback loop is created, time and causality become complicated. In causal circles, cause and effect can be simultaneous rather than sequential. Once we conceive of consequences, the future becomes part of the present and we can base our actions on how the future will (or should) be.

These ideas of the “imagined future” are similar to the concept of episodic simulation proposed by Dan Schachter and his colleagues (Schachter, 2012; Szpunar et al., 2014) and the thoughts behind Carl Hoefer’s Freedom from the inside out (2002).

Such future-directed thought can have a top-down effect on the present. In particular, acts of free will can form a “self” – a set of predispositions to act in a characteristic way, sometimes automatically and sometimes deliberately (Kane, 2011, 2014).

Every undetermined self-forming choice is the initiation of a novel pathway into the future, whose justification lies in that future and is not fully explained by the past.” (Kane, 2011)

In a way the exercise of free will is like setting a legal precedent. Past decisions can then contribute to present choices.

Return to the Scenario

And so we return to the hypothetical wager from the beginning of this post. Should we bet that our actions cannot be predicted? Will it be possible 20 years from now for a brilliant neuroscientist to predict our actions before they occur?

In the experiments of Eddy Nahmias and colleagues (2014), subjects were asked about just such a scenario: a future neuroscientist reads the brain activity of a person called Jill and predicts what Jill will do. More than 80% of subjects accepted that this will be possible, but still claimed that Jill has free will if she is acting according to her own reasons. They believe that “the brain scanner is simply detecting how free will works in the brain” (Nahmias, 2015).

The astute among you may wonder whether during the scan you could fervently and honestly intend to press the red button. But then, once you have made your bet, on second thought you might wilfully decide to press one of the other buttons. After all, even at the last millisecond you can change your mind. You do not usually do this. That is why the brain scanner can often predict your behavior. But you always can change your mind.

I would take the bet.

Conclusion

I have considered physical determinism and pointed out its limitations in quantum uncertainty, chaos and incomputability. I have shown that complete determinism is in logical conflict with free will. I have reviewed some of the evidence that suggests that our unconscious brain determines what we might falsely believe to be our free choices. And I have refused to accept that evidence, arguing that we are still free whenever we base our actions on an evaluation of their consequences.

Determinism rules but only within limits. At the level of the atom there is quantum uncertainty. At the level of the brain there is conscious choice.

In our brains, most of what happens follows the laws of determinism, with the past causing the present and the present causing the future. Most of what we do is unconscious. Yet some acts are deliberately chosen after a conscious evaluation of what will happen. These are as much determined by the imagined future as by the actual past. As such they are both determined and free.

Note: This posting was derived from a talk given at the Rotman Research Institute Annual Conference. A pdf of the slides and the notes for the talk is available for download.

References

Barrett, P. H., Gautrey, P. J., Herbert, S., Kohn, D., & Smith, S. (1987). Charles Darwin’s notebooks, 1836-1844: Geology, transmutation of species, metaphysical enquiries. London: British Museum (Natural History).

Baumeister, R. F., Masicampo, E. J., & DeWall, C. N. (2009). Prosocial benefits of feeling free: Disbelief in free will increases aggression and reduces helpfulness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 35, 260-268.

Binder, P.-M. (2008). Theories of almost everything. Nature, 455, 884-885.

Bourget, D. & Chalmers, D. J. (2014). What do philosophers believe? Philosophical Studies, 170, 465-500.

Burton, R. A. (2002). On being certain: believing you are right even when you’re not. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Collins, G. P. (2009). Within any possible universe, no intellect can ever know it all. Scientific American, March, 2009,

Dennett, D. C. (1978). Brainstorms: Philosophical essays on mind and psychology. Montgomery, VT: Bradford Books. (Chapter 15. On giving libertarians what they say they want. pp. 286-299).

Dennett, D. C. (2003). Freedom evolves. New York: Viking.

Earman, J. (1986). A Primer on Determinism. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Edelman, G. (1987). Neural Darwinism. The theory of neuronal group selection. New York: Basic Books.

Filevich, E., Kühn, S., & Haggard, P. (2013). There is no free won’t: antecedent brain activity predicts decisions to inhibit. PLoS ONE 8(2): e53053. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0053053

Fried, I., Mukamel, R., & Kreiman, G. (2011). Internally generated preactivation of single neurons in human medial frontal cortex predicts volition. Neuron, 69, 548–562.

Gazzaniga, M. S. (2011). Who’s in charge? Free will and the science of the brain. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Graffin, G., & Provine, W. (2007). Evolution, religion and free will. American Scientist, 95(4), 294-297

Harris, S. (2012). Free will. New York: Simon & Schuster (Free Press).

Hilgevoord, J., & Uffink, J. (2006). The Uncertainty Principle. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Hoefer, C. (2002). Freedom from the inside out. In C. Callender (Ed.) Time, Reality and Experience. (pp. 201–222). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Hoefer, C. (2010). Causal determinism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Hoffstaedter, F., Grefkes, C., Zilles, K., & Eickhoff, S. B. (2013). The “What” and “When” of self-initiated movements. Cerebral Cortex, 23, 520-530.

Ismael, J. (2015). Quantum mechanics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Jones. E. (1908). Rationalisation in every-day life. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 3, 161-169.

Kane, R. (2011). Rethinking free will: New perspectives on an ancient problem In R. Kane (Ed.) Oxford handbook of free will. 2nd Edition. (pp 381-404). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kane, R. (2014). Acting ‘of one’s own free will: Modern reflections on an ancient philosophical problem. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, 114, 35-55.

Laplace P. S. (1812, revised 6th edition 1840, translated by Truscott, F.W. & Emory, F. L., 1902, reprinted 1951) A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities, New York: Dover Publications. (quotation is from p.4)

Libet, B., Wright, E. W., Jr. & Gleason, C. A. (1982). Readiness-potentials preceding unrestricted “spontaneous” vs. pre-planned voluntary acts. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 54, 322-35.

Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain, 106, 623–642.

Libet, B. (1985). Unconscious cerebral initiative and the role of conscious will in voluntary action. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 8, 529-566.

Lloyd, S. (2012). A Turing test for free will. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, A 28, 3597-3610.

Lorenz, E. (1996). The essence of chaos. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Lorenz, E. (2005). Quoted in 2013 by C. M. Danforth on his blog Mathematics of Planet Earth, Chaos in an atmosphere hanging on a wall.

Nahmias, E., Morris, S., Nadelhoffer, T, & Turner, J. (2005). Surveying freedom: Folk Intuitions about free will and moral responsibility. Philosophical Psychology, 18, 561–584.

Nahmias, E., Shepard, J., & Reuter, S. (2014.) It’s OK if ‘my brain made me do it’: People’s intuitions about free will and neuroscientific prediction. Cognition, 133, 502–516.

Nahmias, E. (2015). Why we have free will. Scientific American, 312(1), 76-79.

Rosenberg, A. (2011). The atheist’s guide to reality: Enjoying life without illusions. New York: W.W. Norton.

Roskies, A. L. (2010). How does neuroscience affect our conception of volition? Annual Review of Neuroscience, 33, 109-130

Schacter, D. L. (2012). Adaptive constructive processes and the future of memory. American Psychologist, 67, 603-613.

Soon, C. S., Brass, M., Heinze, H. J., & Haynes, J. D. (2008). Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nature Neuroscience, 11, 543–545.

Soon, C. S., He, A. H., Bode, S., & Haynes, J.D. (2013). Predicting free choices for abstract intentions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 110, 6217-6222.

Szpunar, K. K., Spreng, R. N., & Schacter, D. L. (2014). A taxonomy of prospection: Introducing an organizational framework for future-oriented cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 111, 18414-18421.

van Inwagen, P. (1983). An essay on free will. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

van Inwagen, P. (2008). How to think about the problem of free will. Journal of Ethics, 12, 327-341.

Vohs, K. D., & Schooler, J. (2008). The value of believing in free will: Encouraging a belief in determinism increases cheating. Psychological Science, 19, 49-54.

Wegner, D. M. (2002). The illusion of conscious will. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Wolpert, D. H. (2008). Physical limits of inference. Physica D, 237(9), 1257–1281. (For lay summaries see Binder, 2008, and Collins, 2009).

Wright, R. (1994). The moral animal: Evolutionary psychology and everyday life. New York: Pantheon Books.