In 1891 Mary Cassatt (1844-1926) exhibited a set of ten color prints at the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris. These prints had been made using new aquatint procedures that allowed the artist to print solid blocks of color. The colors and patterns owed much to the Japanese woodblock prints which had recently been exhibited at the Ecole des Beaux Arts. Another source of the imagery was the work of Edgar Degas (1834-1917), with whom Cassatt had previously worked on black and white etchings and aquatints. Though printed in a small edition size of 25, Cassatt’s 1891 prints did not sell well, perhaps because they were too innovative for the market. Now they are appreciated as key contributions to the art of the modern print.

Biographical Notes

Mary Cassatt was born near Pittsburgh. Her family was well-to-do and she spent time in Europe as a child, becoming fluent in French and German. From 1861 to 1864 she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Art in Philadelphia. In 1866 she continued her studies in Paris. Returning to North America she was unable to find patrons. Although her family advised her not to continue with her art, she returned to Paris in 1871. There she became good friends with Edgar Degas, who invited her to exhibit her work in the Third Impressionist Exhibition in 1877. Thereafter her paintings began to sell, and she continued to live in Paris until her death. Her paintings mainly concerned the day-to-day life of women and children. Cassatt soon met Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), and together they gave the Impressionists a feminist frisson. More details of Cassatt’s life are available in Matthews (1994). The illustration below shows a self portrait of Cassatt made in 1880 using gouache and watercolors over a graphite drawing, and an earlier oil-on-canvas self-portrait of Degas from 1863.

Early Etchings of Degas and Cassatt

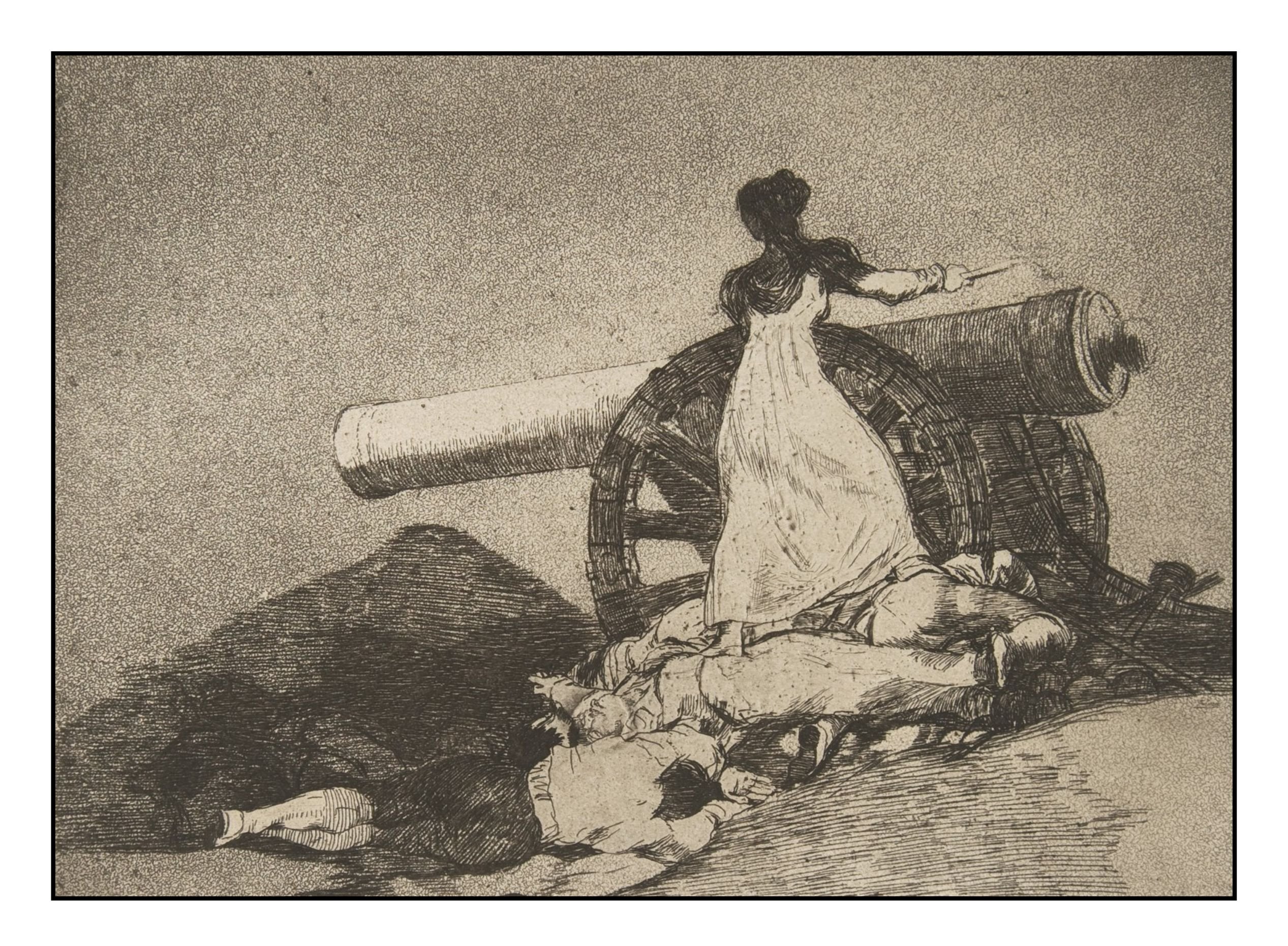

In the late 1870s Degas and Cassatt became interested in etching. They were particularly intrigued by the techniques of aquatinting that had become popular over the past century or so (Lumsden, 1962; Eichenberg, 1976; Leaf, 1984). In simple etchings, differently shaded areas of the image can be created by cross-hatching. Aquatint allowed the artist to produce more homogenous shades of grey (or sepia). The artist scatters rosin granules over the engraved copper plate. The granules are then fused to the plate by heating. This creates a finely irregular surface that its then etched with acid. Regions of the print can be stopped-out by applying varnish or some other smooth coating, thus limiting the extent of the shading. Different levels of greyness can be obtained by multiple printings. Francisco Goya (1746-1828) was the first and greatest master of the aquatint. The following is one of the prints from his 1810 series on The Disasters of War.

In 1879 Edgar Degas made some sketches of Mary Cassatt and her sister Lydia at the Louvre. This led to the pastel illustrated below on the left. He then rearranged the figures from the sketches and the pastel and provided a different background – the Etruscan sculptures in the museum – to make the etching and aquatint shown on the right.

Later in 1880, he rearranged the figures once more and made the aquatint-etching shown on the left below. The vertical arrangement of the figures probably derived from the Japanese hashira-e prints designed to adorn the pillars in houses (Ives, 1974, p 37). Many Japanese prints had been exhibited at the Paris Universal Exposition in 1878. Several years later in 1885, Degas colored one of these prints using pastels – as shown on the right (Boggs, 1988, p 440). Color was essential to Impressionism. For a truly Impressionist print, one would need a way to add color.

Cassatt also began using the techniques of etching and aquatint. The following illustration shows on the left one of Cassatt’s famous paintings – Woman with a Pearl Necklace in a Loge (1879). The young woman (her sister Lydia) is shown at the opera seated in front of a mirror which reflects her back and the other loge seats at the opera. On the right is an etching-aquatint of a similar image from 1880.

Japanese Woodblock Prints

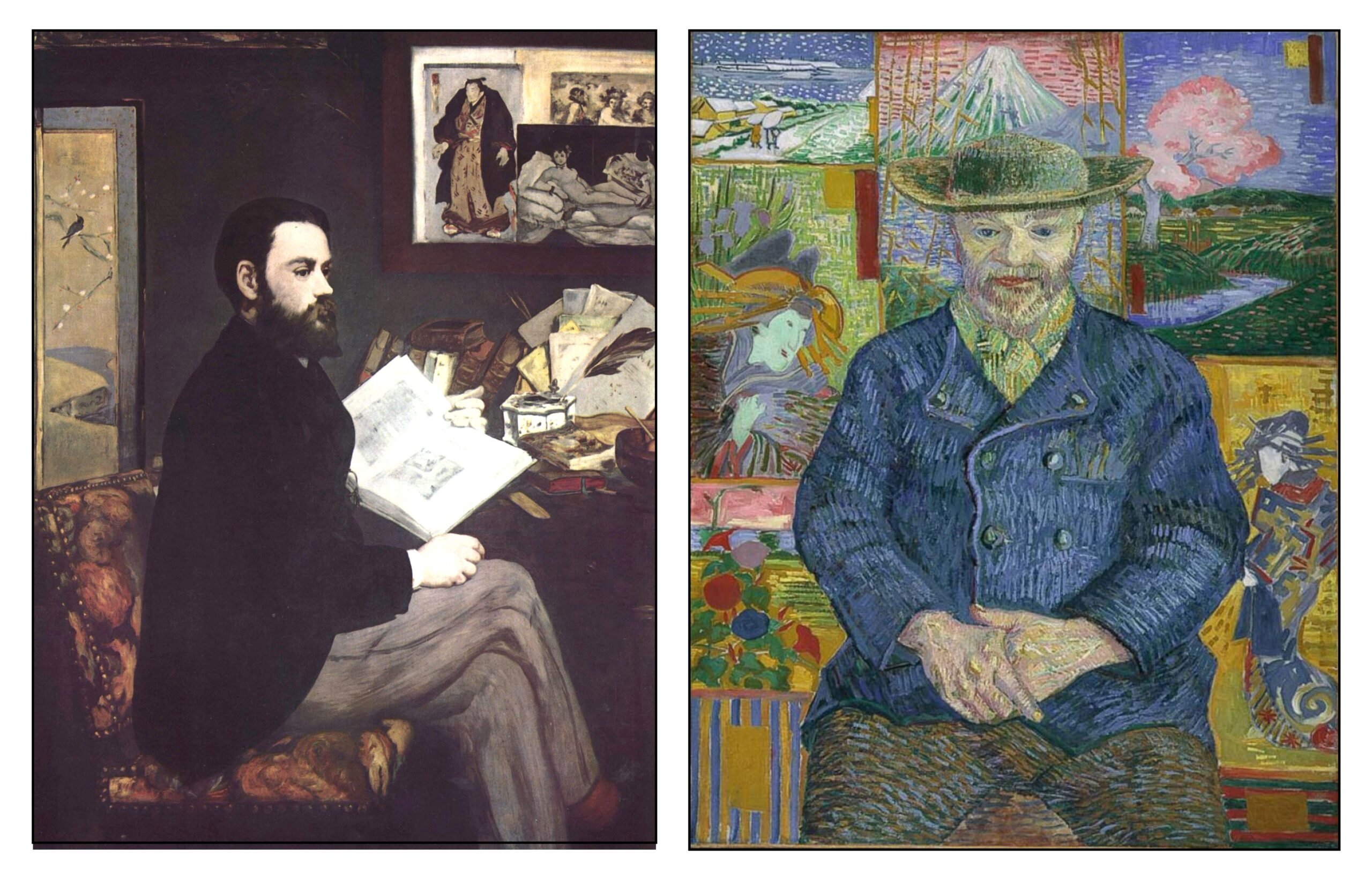

During the second half of the 19th Century, Japan opened its doors to the world, and Europe became aware of Japanese art. Japonisme became the rage in Paris. Artists were particularly intrigued by the woodblock prints, called ukiyo-e or “pictures of the passing world” (Ives, 1974). Western painters began to experiment with the use of flat colors, clear outlines, and textural patterns characteristic of these Japanese prints. Some painters included the prints in the background of their portraits: Manet’s portrait of Emile Zola (1868), and Van Gogh’s portrait of Pere Tanguy (1887):

In 1890 there was a huge exhibition of Japanese prints at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. Cassatt visited with Degas, and then urged Morisot to join her in a second visit:

… we could go to see the Japanese prints at the Beaux Arts. Seriously you must not miss that. You who want to make color prints you couldn’t dream of anything more beautiful. I dream of it and don’t think of anything else but color on copper. (letter quoted by Matthews & Shapiro, 1989, p 36)

Cassatt was completely entranced by the prints. She was able to purchase many examples, particularly by Utamaro Kitagawa (1753-1806), who portrayed the life of the geisha, or courtesan, in Edo, now known as Tokyo (Davis, 2007). The following prints are examples of his work: Reading a Letter (1802), Using Two Mirrors to Observe her Coiffure (1793) and Mother and Child (1793). Cassatt owned copies of the latter two prints. The print on the right is intricately constructed: a geisha seated behind a screen sticks out her tongue at her child while applying her makeup; the child points to her image in the mirror while being restrained by a maiko (apprentice geisha) who is trying to suppress her laughter.

Cassatt’s Prints

Over the next year Cassatt made ten prints in the style of the ukiyo-e. She described her work as “un essai d’imitation de l’estampe japonaise” (an attempt to imitate Japanese prints, Johnson 1990). Rather than using woodblocks, she combined etching with aquatint. Instead of ink she applied watercolors over the aquatinted areas using a wad of cloth (called a “doll” giving the technique the name à la poupée). Although other artists tended to leave the process in the hands of the printer, Cassatt herself was responsible for the coloring of each print. She described her technique:

My method is very simple. I drew an outline in drypoint and transferred this to two other plates, making in all, three plates, never more for each proof. Then I put on aquatint wherever the color was to be printed; the color was painted on the plate as it was to appear in the proof. (quoted by Johnson 1990)

Cassatt used three colors in her prints. Rather than using primary colors and allowing shades to form by combinations of the basic colors, she chose her own set of three colors for each print. These colors were not as bright as those in a new ukiyo-e print, but were like the colors in the faded prints that were available in Europe at that time (Johnson, 1990).

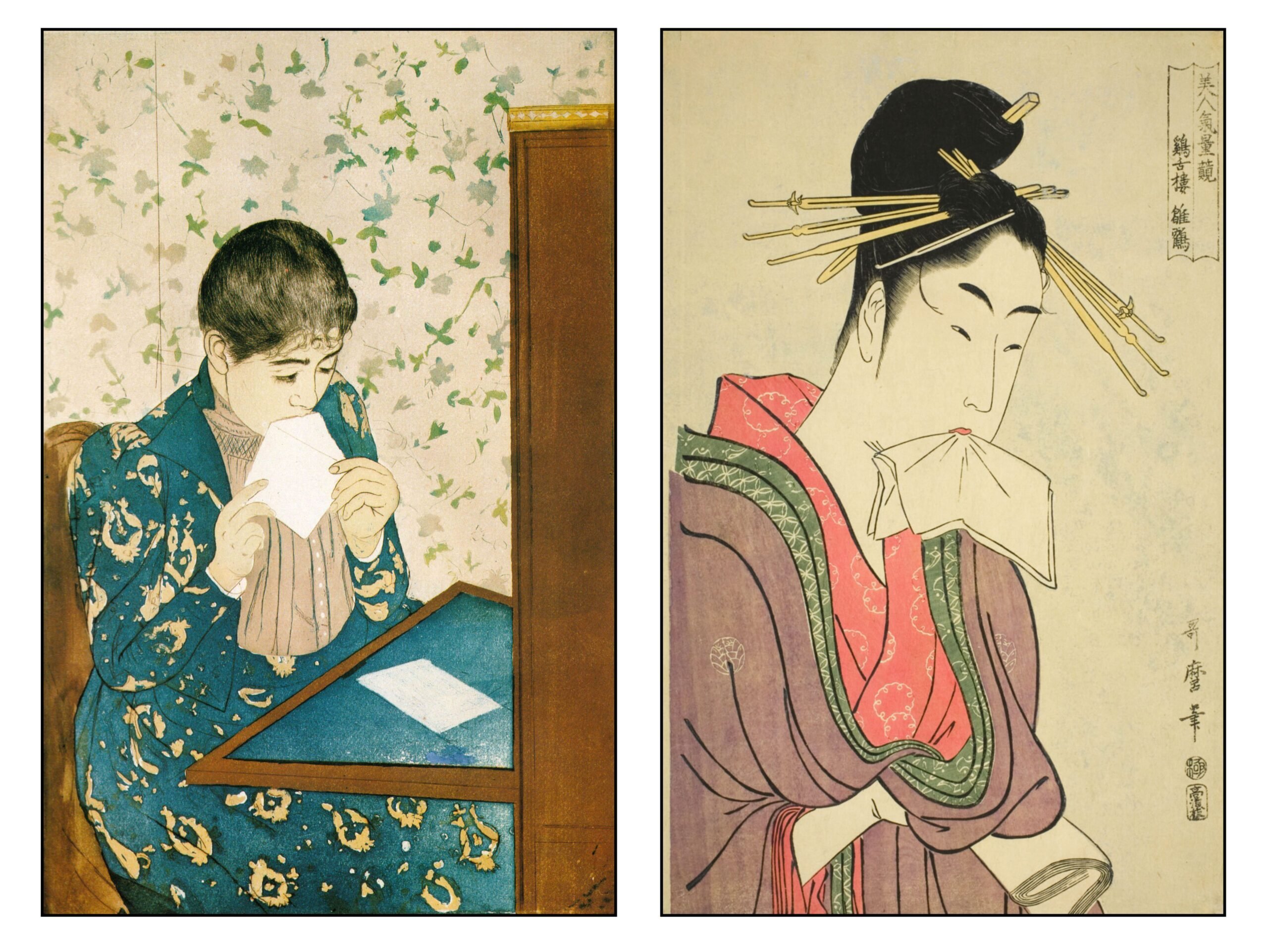

In the print The Letter, a young woman at her writing desk licks the envelope for mailing a letter. One imagines that this must be a love letter. The print recalls ukiyo-e images of geishas with a towel at their mouth, such as Utamaro’s portrait of Hinazuru of the Kaisetsuro (1795) shown on the right. Cassatt was likely unaware that this gesture alludes to the geisha’s postcoital state (Johnson, 1990). Cassatt renders the patterns of her subject’s dress with the same elegance as the Japanese printmakers crafted the patterns in a geisha’s kimono. Unlike most ukiyo-e prints, in which the figures are shown on a plain background, Cassatt’s print also depicts complementary patterns in the wallpaper behind the letter writer.

Cassatt’s print of The Fitting shows a woman standing before a mirror while a seamstress adjusts her new dress. The vertical alignment of the figures alludes to Japanese prints portraying a geisha with her attendant maiko, such as the 1795 Utamaro print on the right.

Cassatt colored each print individually and different prints from the same plates sometimes display a wide range of colors. This is shown below in two versions of the print Maternal Caress (from the Art Institute of Chicago and from the Worcester Art Museum).

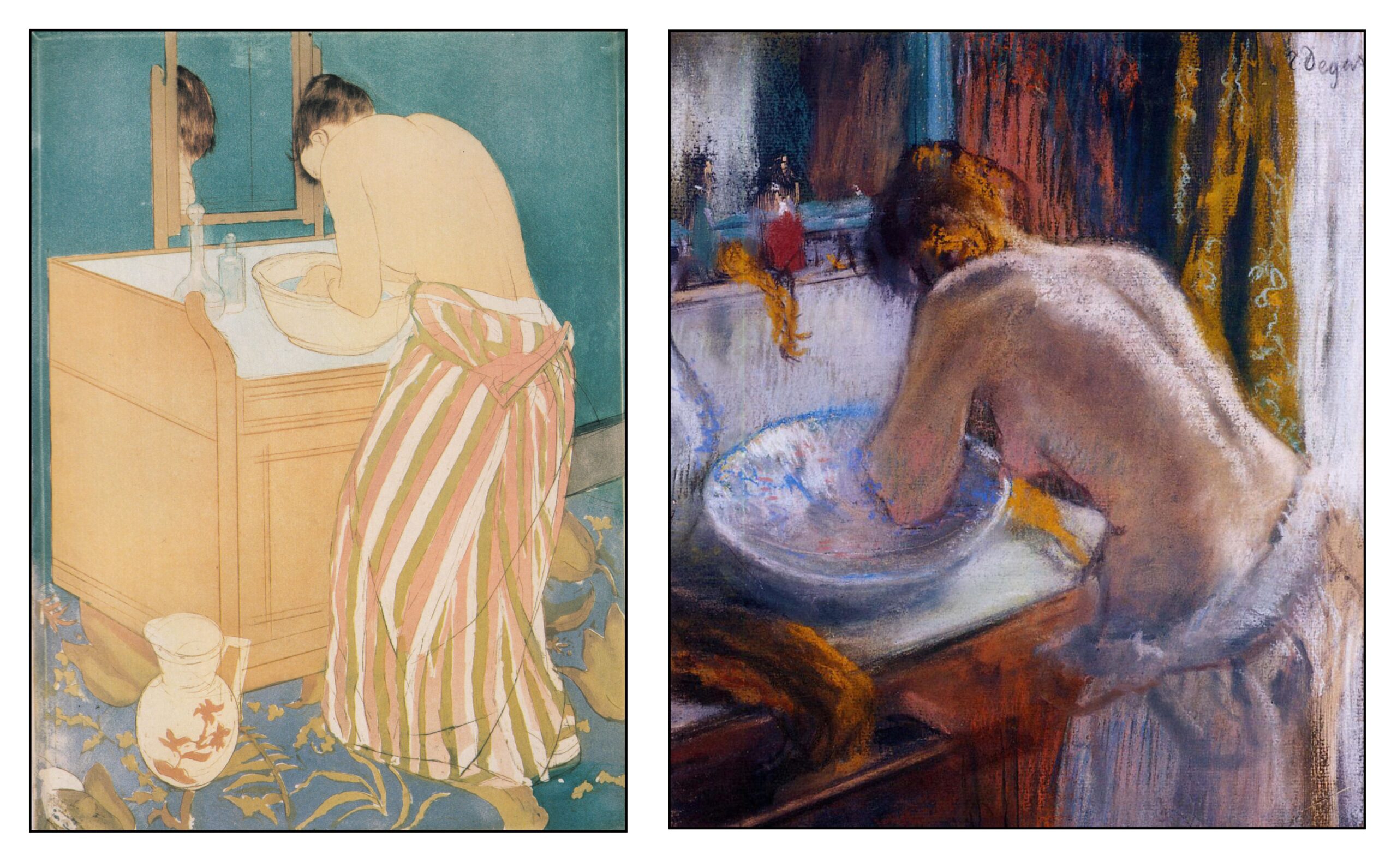

My favorite print from the 1891 set is Woman Bathing. A woman at her washstand has undone the upper part of her bathrobe letting it fall to her waist. She then proceeds to wash her face and upper body.Her head is partially reflected in the mirror. The vividly patterned carpet and the plain blue wall contrast with the simple stipes of her robe. At the lower left, the simple decoration on the water jug contrasts with the more florid patterns in the carpet. Cassatt’s image is related to some of the Degas pastels of bathing women such as his 1884 painting illustrated on the right.

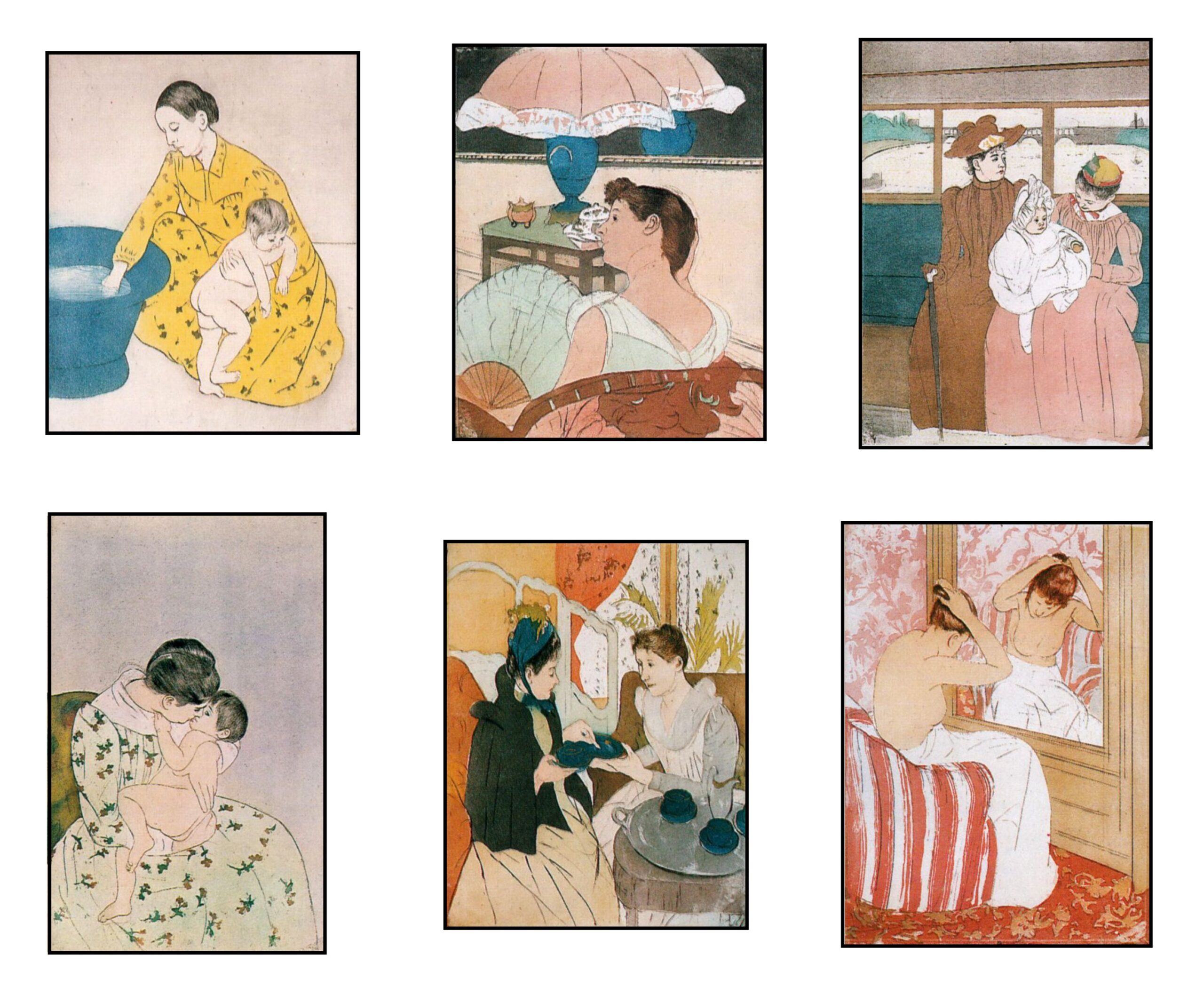

The other six prints in the 1891 set are shown below: The Bath, The Lamp, In the Omnibus, Mother’s Kiss, Afternoon Tea Party and The Coiffure. More information is provided in the excellent book Mary Cassatt: the Color Prints (1989) by Mathews and Shapiro. A set of the prints can be viewed at the website of the National Gallery of Art.

Envoi

Though Degas and Pissarro were impressed by Cassatt’s 1891 prints, the general response to her exhibition was one of indifference. Only a few prints were purchased and Cassatt was unable to sell out the small edition of 25 during her lifetime. Other artists began to explore different methods of making color prints. Over time lithography became the most popular technique. Nevertheless, Cassatt’s 1891 set of colored aquatints remains as an isolated masterpiece in the history of the modern print:

As a whole, the series is a remarkably successful group based on clarity and elegance of composition, on flat, abstract patterning, and on a powerful economy of line (Johnson, 1990).

The prints portray the life of women, involved in the day-to-day activities of caring for children, writing to friends, travelling on the bus, and taking tea. The women are beautiful, and some of the prints have an erotic charge. Most importantly, the women are viewed sympathetically: they are not the objects of a male gaze.

References

Boggs, J. S. (1988). Degas. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Davis, J. N. (2007). Utamaro and the spectacle of beauty. Reaktion Books.

Eichenberg, F. (1976). The art of the print: masterpieces, history, techniques. H. N. Abrams.

Ives, C. F. (1974). The Great Wave: The Influence of Japanese Woodcuts on French Prints. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Johnson, D. (1990). Cassatt’s color prints of 1891: the unique evolution of a palette. Notes in the History of Art, 9(3), 31-39.

Leaf, R. (1984). Etching, engraving, and other intaglio printmaking techniques. Dover Publications.

Lumsden, E. S. (1962). The art of etching: a complete & fully illustrated description of etching, drypoint, soft-ground etching, aquatint & their allied arts, together with technical notes upon their own work by many of the leading etchers of the present time. Dover Publications.

Mathews, N. M., & Shapiro, B. S. (1989). Mary Cassatt: the color prints. H.N. Abrams.

Mathews, N. M. (1994). Mary Cassatt: a life. Yale University Press.

Leave a Reply