Robert Lowell (1917-1977) was one of the most important American poets of the mid-20th-Century. He was famous both for his contribution to poetry and for his recurrent attacks of mania. This post reviews his life, comments on some of his poems, and considers the relations between creativity and mood disorders. Madness sometimes goes hand-in-hand with poetry:

Lovers and madmen have such seething brains,

Such shaping fantasies, that apprehend

More than cool reason ever comprehends

The lunatic, the lover and the poet

Are of imagination all compact

(Shakespeare, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, V, 1, 5-9)

Family Background

Robert Traill Spencer Lowell IV, as his full name suggests, was born to a long line of “Boston Brahmins,” a term that Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. coined to describe the an untitled aristocracy with ancestors among the original Protestant colonists who came to New England in the 17th Century.

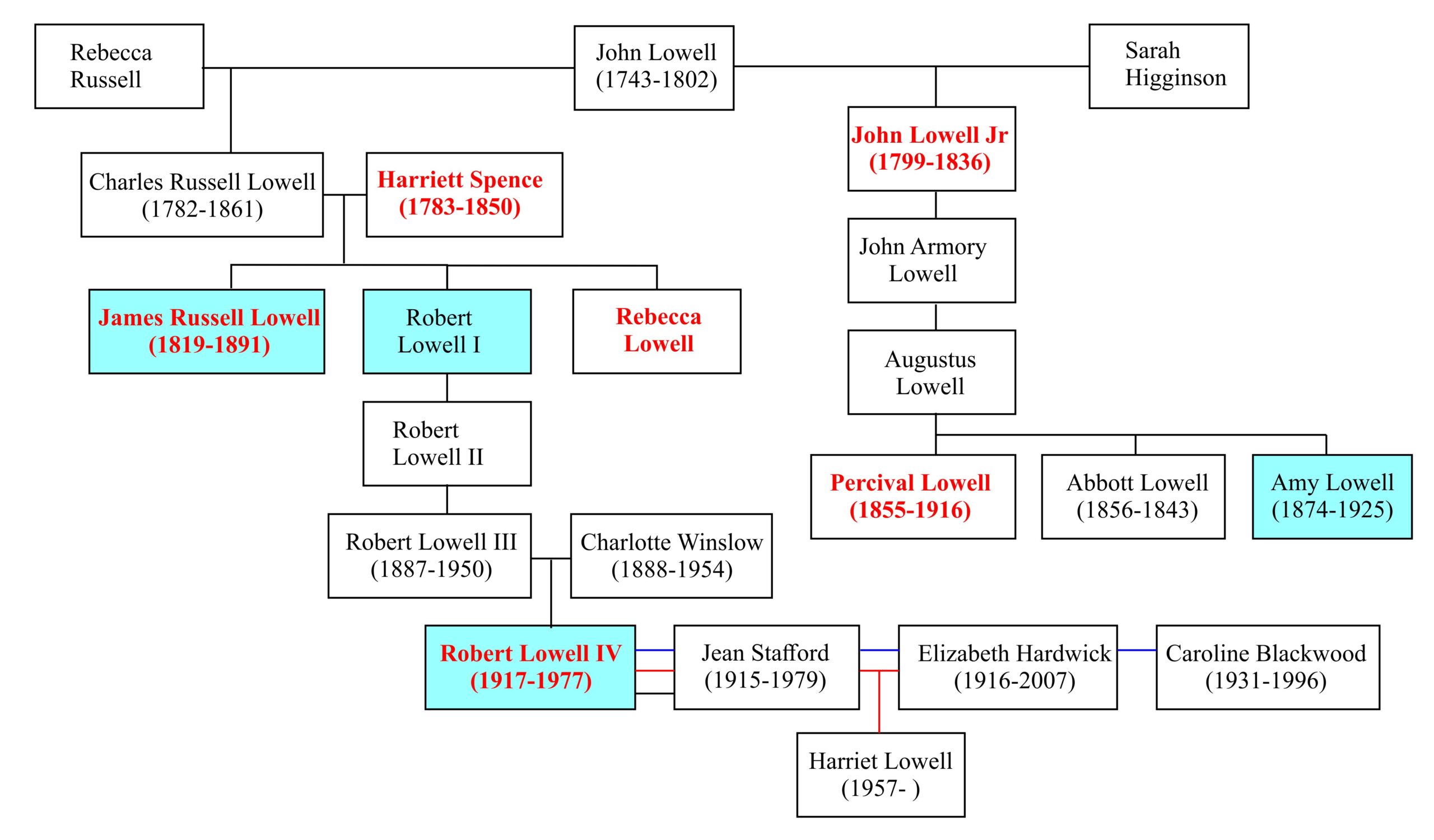

The following figure shows part of Lowell’s family tree (Jamison, 2017, pp 39-51; also websites by Wikipedia, Geneanet, and Nicholas Jenkins). The diagram begins with John Lowell (1743-1802), a judge in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, remembered for authoring Article I of the United States Bill of Rights:

All men are born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential and inalienable rights, among which may be reckoned the right of enjoying and defending their lives and liberties.

The Lowell family tree is noteworthy for the incidence of published poets (light blue shading) and mental disturbances (red lettering). In 1845, Lowell’s great-great-grandmother Harriett Bracket Spence was institutionalized for incurable madness in the McLean Asylum for the Insane in Somerville. The hospital later moved to Belmont and became known simply as McLean Hospital (Beam, 2003). Lowell was himself committed there for treatment on several occasions between 1958 and 1967.

Charles Russell Lowell was considered one of the “fireside poets,” a group which included Longfellow, Whittier and Bryant. These were poets whose work was read aloud to the family at the fireside. Amy Lowell became fascinated by Chinese poetry, which she attempted to imitate in brief intensely visual poems, a style that came to be known as “Imagism.” Percival Lowell was an astronomer who falsely believed that the markings he observed on the planet Mars represented a network of canals.

Through his mother, Charlotte Winslow, Lowell was a direct descendent of Mary Chilton (1607-1679), who arrived on the Mayflower in 1620. On this father’s side, he could trace their ancestry back to a Percival Lowle (1571-1664), who settled just north of Boston some 20 years after the Mayflower arrived.

Youth

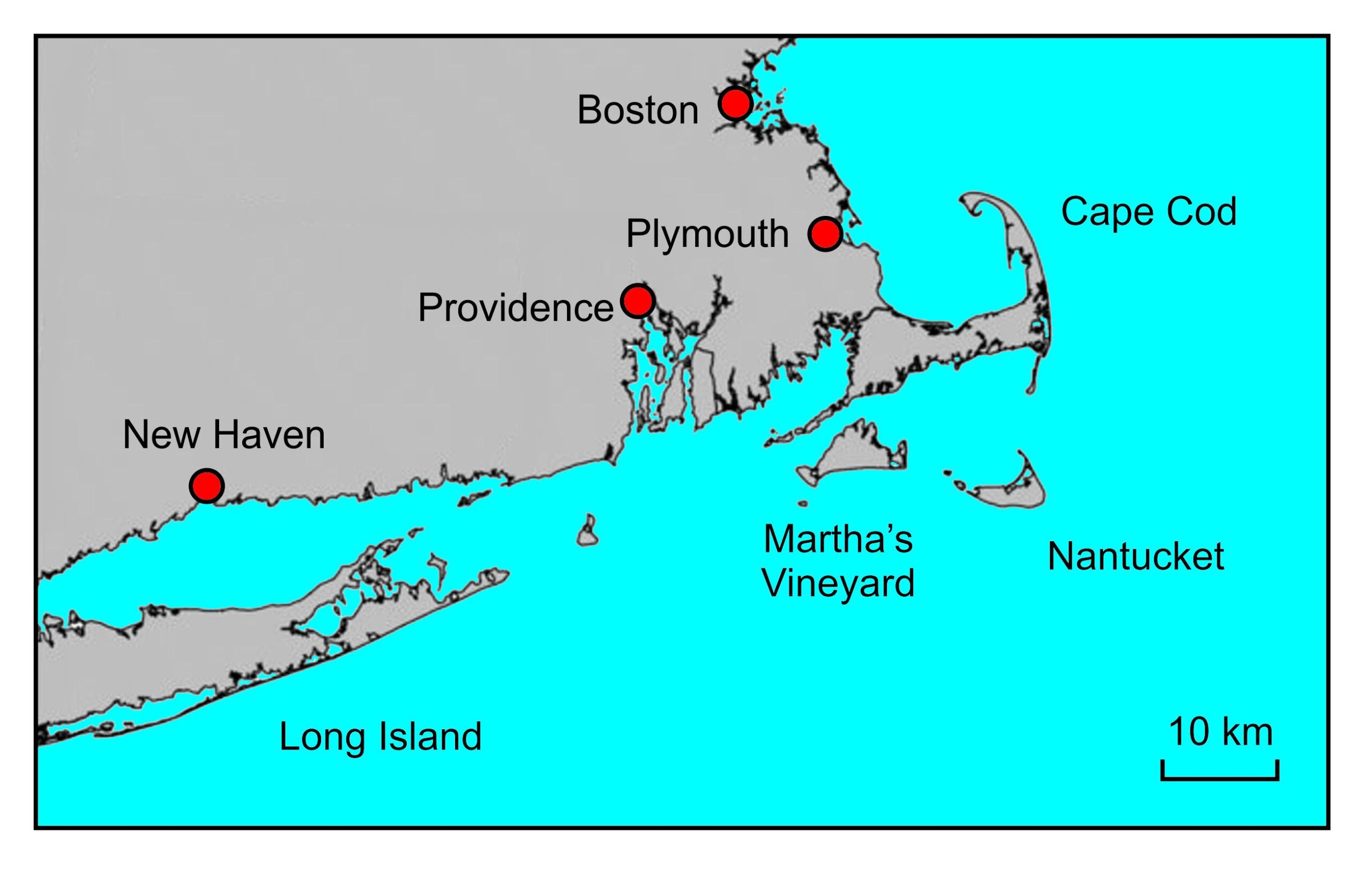

While attending St Mark’s, an Episcopal preparatory school in Southborough, just south of Boston, Lowell was significantly influenced by a young teacher and poet, Richard Eberhart, and decided that poetry was his calling. He spent the summers of 1935 and 1936 with his friends, Frank Parker and Blair Clark, in a rented cottage on Nantucket Island just south of Cape Cod (see map below). There, under Lowell’s domineering direction, the three engaged in an impassioned study of literature and art. Lowell came to be known as “Cal,” a nickname that derived from both the Roman Emperor Caligula and Shakespeare’s character Caliban (Hamilton, 1982, p 20).

Lowell attended Harvard University but after two years left to study with the poet Allen Tate, finally graduating from Kenyon College in 1940. After graduation, he married Jean Stafford (McConahay, 1986), started graduate studies in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, converted from his family’s Protestant religion to Roman Catholicism, and began writing the poems for his first book. These were days of decision.

When the United States entered World War II in 1941, Lowell initially registered for the draft. However, he soon became upset with the Allied policy of “strategic” bombing: attacking civilian targets to undermine morale, as opposed to the “tactical” bombing of military targets. After receiving orders for his induction into the armed forces in 1943, he wrote an open letter to President Roosevelt describing his objections:

Our rulers have promised us unlimited bombings of Germany and Japan. Let us be honest: we intend the permanent destruction of Germany and Japan. If this program is carried out, it will demonstrate to the world our Machiavellian contempt for the laws of justice and charity between nations; it will destroy any possibility of a European or Asiatic national autonomy; it will leave China and Europe, the two natural power centers of the future, to the mercy of the USSR, a totalitarian tyranny committed to world revolution and total global domination through propaganda and violence.

In 1941 we undertook a patriotic war to preserve our lives, our fortunes, and our sacred honor against the lawless aggressions of a totalitarian league: in 1943 we are collaborating with the most unscrupulous and powerful of totalitarian dictators to destroy law, freedom, democracy, and above all, our continued national sovereignty. (quoted in Hamilton, 1982, p. 89)

Lowell was sentenced as a Conscientious Objector to a year and a day at the Federal Correctional Center in Danbury Connecticut. He was released on parole after 5 months, and spent the rest of his sentence working as a cleaner in the nearby Bridgeport hospital. At the end of this period, his first book, Land of Unlikeness, was published in a limited edition, to encouraging reviews.

Lord Weary’s Castle

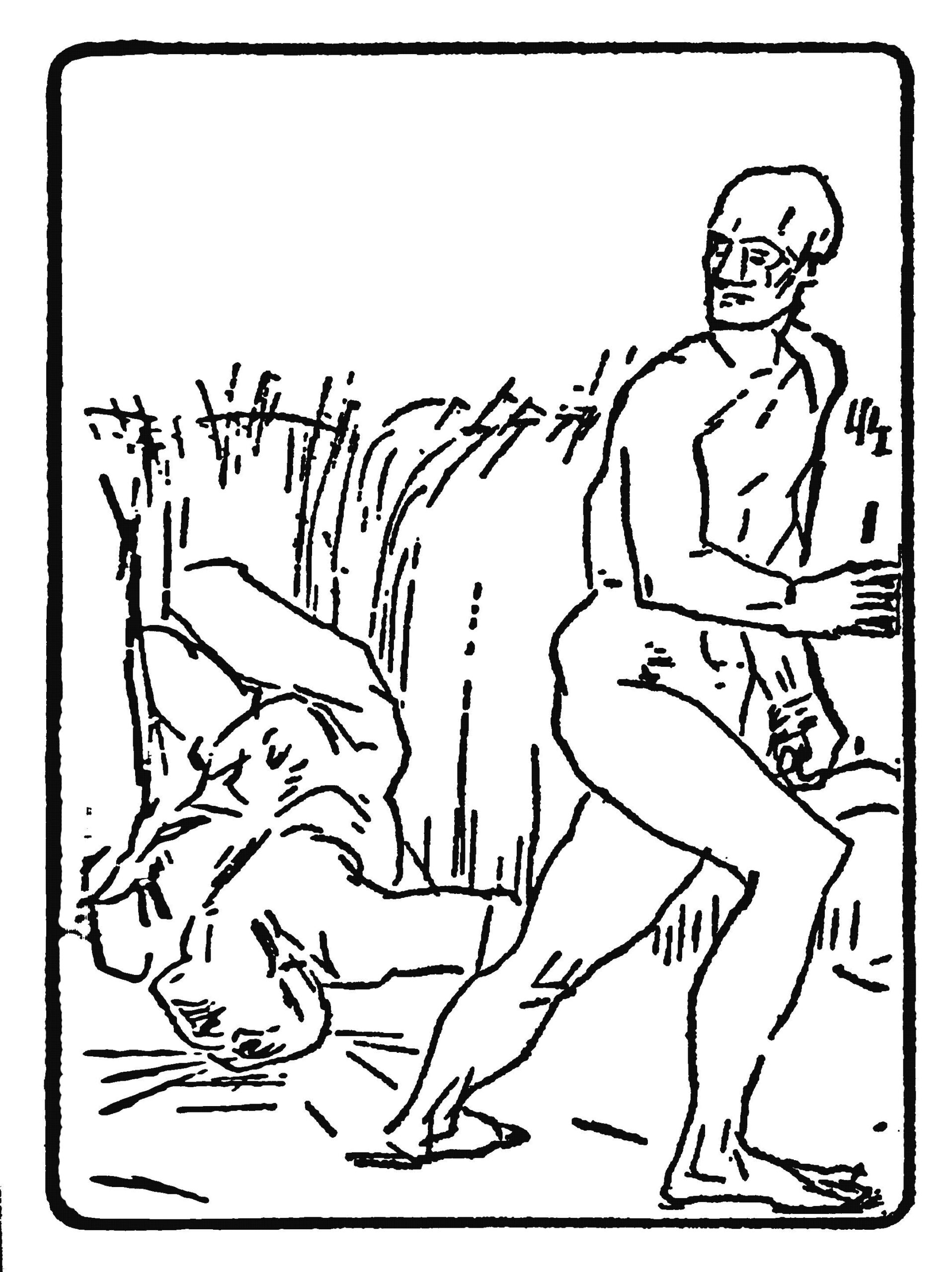

Lowell’s first mainstream book of poetry, Lord Weary’s Castle, was published in 1946 and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize. The title comes from an old ballad about the stonemason Lambkin who built a castle for Lord Weary. After the lord refused to pay for the castle, Lambkin murdered the lord’s wife and child. The frontispiece of the book was an engraving of Cain’s murder of Abel by Lowell’s schoolfriend Frank Parker (right). Title and frontispiece both point to humanity’s long history of violence.

The first poem in the book is The Exile’s Return:

There mounts in squalls a sort of rusty mire,

Not ice, not snow, to leaguer the Hôtel

De Ville, where braced pig-iron dragons grip

The blizzard to their rigor mortis. A bell

Grumbles when the reverberations strip

The thatching from its spire,

The search-guns click and spit and split up timber

And nick the slate roofs on the Holstenwall

Where torn-up tilestones crown the victor. Fall

And winter, spring and summer, guns unlimber

And lumber down the narrow gabled street

Past your gray, sorry and ancestral house

Where the dynamited walnut tree

Shadows a squat, old, wind-torn gate and cows

The Yankee commandant. You will not see

Strutting children or meet

The peg-leg and reproachful chancellor

With a forget-me-not in his button-hole

When the unseasoned liberators roll

Into the Market Square, ground arms before

The Rathaus; but already lily-stands

Burgeon the risen Rhineland, and a rough

Cathedral lifts its eye. Pleasant enough,

Voi ch’entrate, and your life is in your hands.

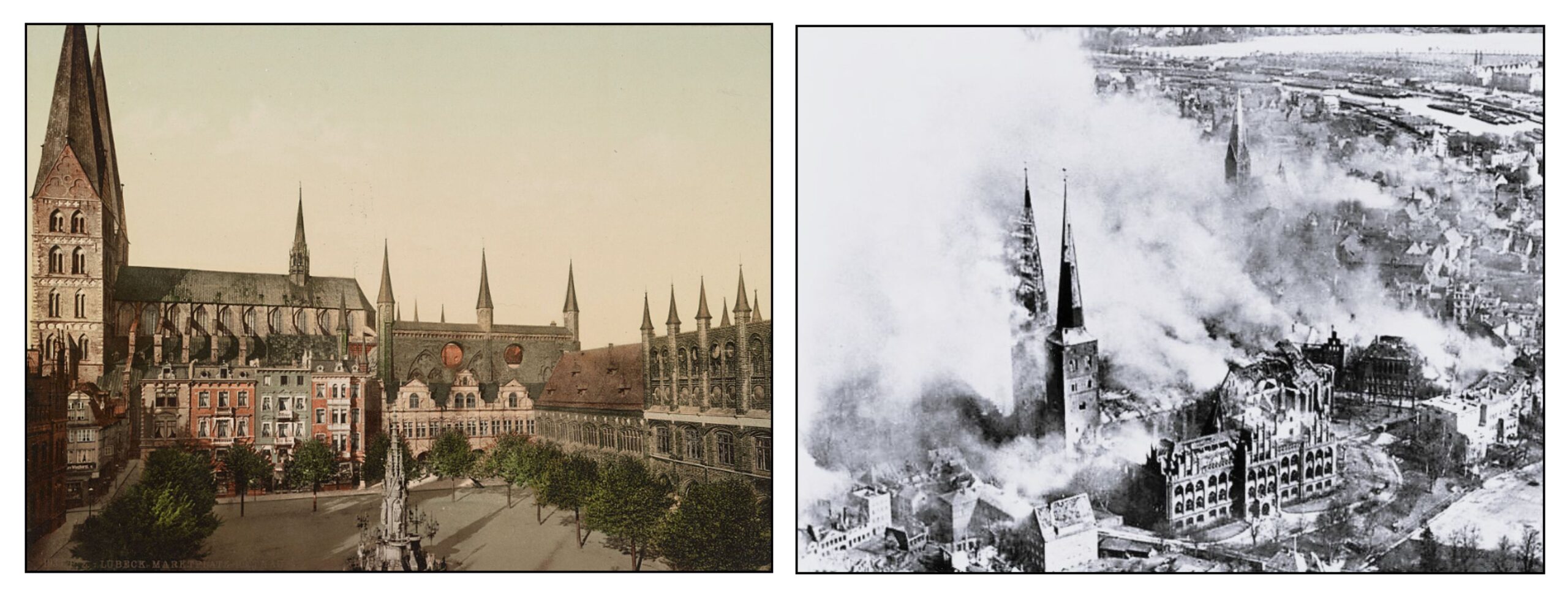

The poem is elusive. In their notes to the Collected Poems (2003), Bidart and Gewanter remark on the similarity of some of the poem’s lines to passages in Thomas Mann’s novella Tonio Kröger, first published in 1903. It recounts the return of a young poet to Lübeck, where he (like the author) had grown up. In the opening lines of the novella, Mann remarks that “sometimes a kind of soft hail fell, not ice, not snow” (Neugroschel translation, 2998, p 164). He also describes Tonio’s father as the “impeccably dressed gentleman with the wildflower in his buttonhole.” (p 180). So we should likely place the poem in Lübeck, though I am not sure why Lowell uses the French term Hôtel de Ville to describe its historic city hall (later referred to by its German name Rathaus).

In 1942 Lübeck was one of the first German cities to be strategically bombed by the Allies. The following illustration shows the Market Square and City Hall in a 1906 postcard together with a photograph of the destruction after the bombing. The Allied attack focused on the city center, which had no military significance; the docks (in the upper right of the photograph) were completely spared.

Lowell’s poem imagines the military occupation of the devastated city. Though there may be hope for some sort of salvation – the lilies probably allude to the Virgin Mary and the Annunciation – the general impression is of the Gates of Hell. The last line quotes from Dante’s Inferno: Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch’entrate (Abandon all hope, you who enter here).

The most important poem of the book is the seven-part The Quaker Graveyard in Nantucket (Axelrod, 2015; Hass, 1977; Remaley, 1976). The poem was written in memory of Lowell’s cousin Warren Winslow, who died in an explosion that sank the destroyer Turner close to Rockaway Point near Coney Island in 1944 (Fender, 1973). The cause of the explosion is not known; it was likely caused by an accident and not by enemy action.

The full poem is available on the website of the Poetry Foundation. The beginning vividly describes the recovery of the body of a drowned sailor:

A brackish reach of shoal off Madaket—

The sea was still breaking violently and night

Had steamed into our North Atlantic Fleet,

When the drowned sailor clutched the drag-net. Light

Flashed from his matted head and marble feet,

He grappled at the net

With the coiled, hurdling muscles of his thighs:

The corpse was bloodless, a botch of reds and whites,

Its open, staring eyes

Were lustreless dead-lights

Or cabin-windows on a stranded hulk

Heavy with sand.

Madaket is a beach on the Southwestern edge of Nantucket. As noted by Bidart and Gewanter, much of the description of the drowned sailor derives from Thoreau’s The Shipwreck (1864). Warren Winslow’s body was never recovered. Lowell’s poem therefore alludes to all those who died at sea in the war. The poem conveys the violence of such deaths with harsh rhymes, irregular rhythms and the striking enjambment of the fourth line.

The second section of the poem further generalizes the tragedy to all those sailors who have died at sea, like those of the 19th Century whalers in Melville’s Moby Dick or the Quaker seamen buried in the Nantucket graveyard. The third section reveals how the sailors failed to understand their deaths. They thought that God was on their side, but did not realize that God was in the sea that drowned them or the whale they tried to kill. The next two sections further describe the violence of the whale trade, and by extension the violence of the war that had just come to an end.

Where might we find redemption from the ongoing violence? The sixth and penultimate section of the poem – Our Lady of Walsingham – changes dramatically from the previous sections. In 1061, Richeldis de Faverches, an Anglo-Saxon noblewoman, received a vision of the Virgin Mary in Walsingham, a small village in Norfolk. Following the Madonna’s request, she built there a replica of Jesus’s home in Nazareth, and placed a statue of the Virgin with the infant Jesus within. This shrine became one of the most visited pilgrimage sites in Europe. In 1538, during Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, the shrine and its associated priory were torn down. (A damaged statue of the virgin in the Victoria and Albert Museum may actually be what remains of the Walsingham statue.) In 1897 a new statue (illustrated on the right) was blessed by the pope and placed in the Slipper Chapel, the last station on the original pilgrimage route to Walsingham. In the 20th Century, Walsingham began to welcome pilgrims again, though now separate Catholic and Anglican sites compete for their visit.

Lowell looks to find salvation but finds indifference:

Our Lady, too small for her canopy,

Sits near the altar. There’s no comeliness

At all or charm in that expressionless

Face with its heavy eyelids. As before,

This face, for centuries a memory,

Non est species, neque decor,

Expressionless, expresses God: it goes

Past castled Sion. She knows what God knows,

Not Calvary’s Cross nor crib at Bethlehem

Now, and the world shall come to Walsingham.

The face of the Virginis indeed “expressionless.” The Latin “there is nothing special nor beautiful about him” is from Isaiah 53:2, which in the Vulgate reads

Et ascendet sicut virgultum coram eo, et sicut radix de terra sitienti. Non est species ei, neque decor, et vidimus eum, et non erat aspectus, et desideravimus eum:

The King James Version translates this verse (and the succeeding three verses) as

For he shall grow up before him as a tender plant, and as a root out of a dry ground: he hath no form nor comeliness; and when we shall see him, there is no beauty that we should desire him.

He is despised and rejected of men; a man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief: and we hid as it were our faces from him; he was despised, and we esteemed him not.

Surely he hath borne our griefs, and carried our sorrows: yet we did esteem him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted.

But he was wounded for our transgressions, he was bruised for our iniquities: the chastisement of our peace was upon him; and with his stripes we are healed.

All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord hath laid on him the iniquity of us all.

This is part of Isaiah’s prophecy of the Messiah, the man of sorrows who will take away our sins. Looking for redemption, the world comes to Walsingham, but the Virgin pays the world no special attention. Our ideas of God being born in human form at Bethlehem and of our salvation through his death on Calvary are human hopes not divine realities.

The final section of the poem describes the Atlantic Ocean as seen from Nantucket:

The empty winds are creaking and the oak

Splatters and splatters on the cenotaph,

The boughs are trembling and a gaff

Bobs on the untimely stroke

Of the greased wash exploding on a shoal-bell

In the old mouth of the Atlantic. It’s well;

Atlantic, you are fouled with the blue sailors,

Sea-monsters, upward angel, downward fish:

Unmarried and corroding, spare of flesh

Mart once of supercilious, wing’d clippers,

Atlantic, where your bell-trap guts its spoil

You could cut the brackish winds with a knife

Here in Nantucket, and cast up the time

When the Lord God formed man from the sea’s slime

And breathed into his face the breath of life,

And blue-lung’d combers lumbered to the kill.

The Lord survives the rainbow of His will.

The poem concludes by remembering how God made man by breathing into his face, and how God later destroyed everyone except Noah and his family in the flood, when huge “combers” (long curling sea waves) covered the earth. The final line likely alludes to the rainbow that God gave as a sign to Noah that he would not flood the Earth again:

And I will establish my covenant with you, neither shall all flesh be cut off any more by the waters of a flood; neither shall there any more be a flood to destroy the earth.

And God said, This is the token of the covenant which I make between me and you and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations:

I do set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between me and the earth. (Genesis 9: 11-13)

The world wars have shown that humanity’s propensity for violence has not improved. One assumes that God will keep his promise. But at what cost? God will survive but humanity may perhaps extinguish itself.

Madness

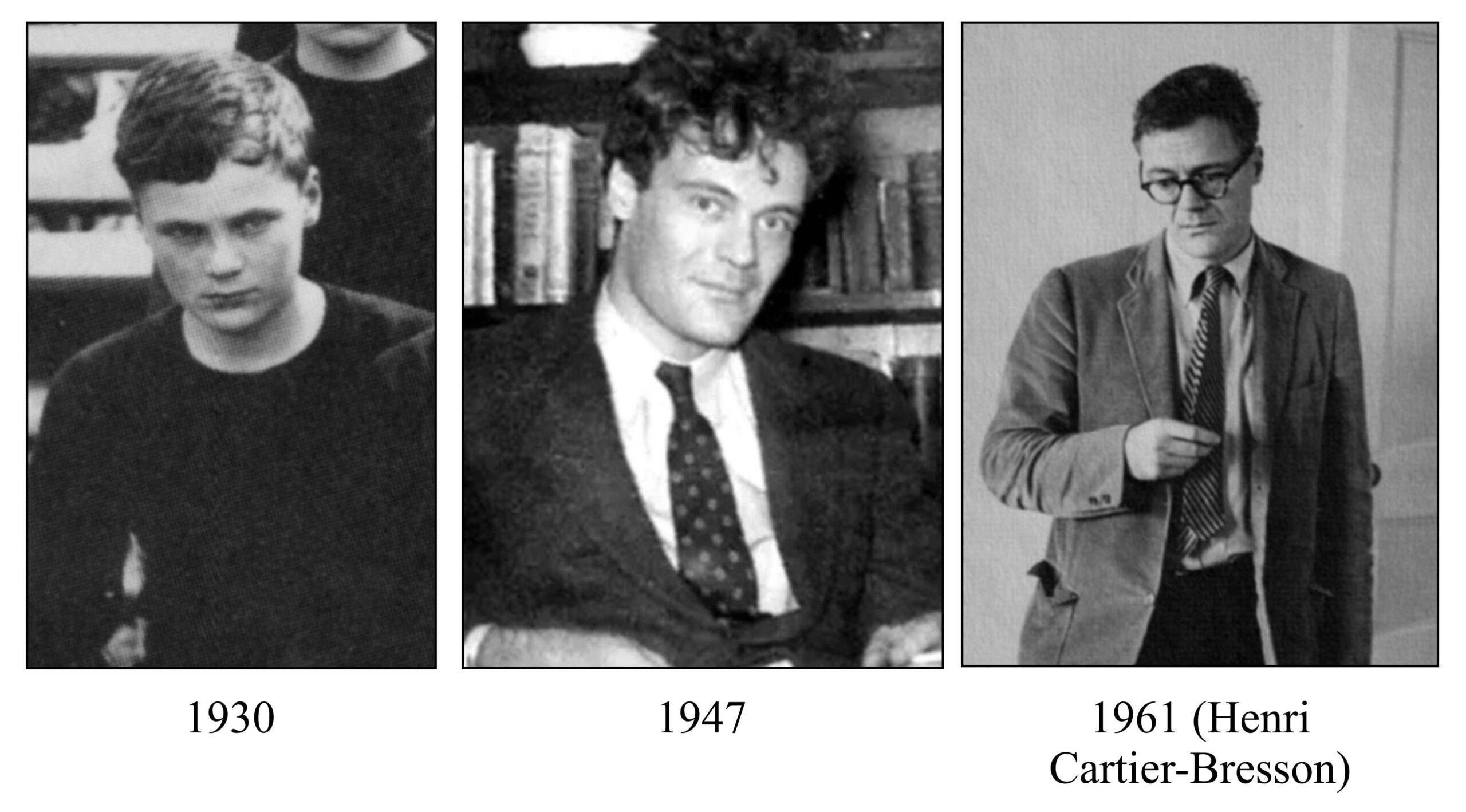

After Lord Weary’s Castle, Lowell became famous. The following illustrations show photographs of him from youth to maturity:

Lowell published his second book The Mills of the Kavanagh in 1948. In early 1949 he started to become “wound up” (Hamilton, 2003, p 140). While teaching at Yaddo, an artists’ community in Saratoga Springs, New York, he became unjustifiably paranoid about a communist takeover of the center. By the time he arrived in Bloomington, Indiana, to give a talk in March, he was frankly psychotic. He later remembered his state of “pathological enthusiasm:”

The night before I was locked up, I ran about the streets of Bloomington, Indiana, crying out against devils and homosexuals. I believed I could stop cars and paralyze their forces by merely standing in the middle of the highway with my arms outspread. Each car carried a long rod above its taillight, and the rods were adorned with diabolic Indian or voodoo signs. Bloomington stood for Joyce ‘s hero and Christian regeneration. Indiana stood for the evil, unexorcized, aboriginal Indians. I suspected I was a re-incarnation of the Holy Ghost and had become homocidally hallucinated. To have known the glory, violence and banality of such an experience is corrupting. (Memoirs, p 190)

Lowell’s mind was experiencing an overwhelming “flight of ideas.” He suffered from delusions of grandeur. His behavior was irrepressible and reckless. He refused to sleep. Lowell was 6-foot 1-inch tall: when he was psychotic, it was extremely difficult to restrain him (Jamison, 2017, p 83). He was finally subdued by the police, and committed to a psychiatric hospital. This was the first of multiple prolonged hospital stays, most lasting several months, that occurred once every year or two from 1949 to 1968 (Jamison, 2017, pp 112-113). Initially, he was treated with Electro Convulsive Therapy. In the 1960s, when the major tranquilizers became available, his bouts of mania were controlled by chlorpromazine. After 1968, treatment with lithium provided him with some respite from his illness. Yet the mania still occasionally occurred.

Each manic attack was followed by a prolonged period of depression. Lowell attributed his depression to his regret and shame over what had happened when he was psychotic. However, they were likely part and parcel of his bipolar mood disorder. Lowell wrote feverishly during the periods just before he went completely manic, He then revised what he had written during his prolonged periods of depression.

Mania and depression are more common in creative individuals than in normal controls and this association appears most prominent for poets (Andreasen & Canter, 1974; Ludwig, 1995; Andreasen, 2008; Jamison, 2017; Greenwood, 2022). The flight of ideas that characterizes mania can easily lead to novel ways of looking at things. This is especially true during the hypomanic phase that precedes the psychotic break, when some modicum of control remains.

Despite his recurring attacks of mania, Lowell continued to write. In his 1959 book, Life Studies, he examined himself and his family in intimate detail. Rosenthal (1967) used the term “Confessional Poetry” to describe this work. Poets had always tapped into their personal experience to write poetry but until now none had been so unabashedly honest about their failings:

Because of the way Lowell brought his private humiliations, sufferings, and psychological problems into the poems of Life Studies, the word ‘confessional’ seemed appropriate enough. Sexual guilt, alcoholism, repeated confinement in a mental hospital (and some suggestion that the malady has its violent phase)—these are explicit themes of a number of the poems, usually developed in the first person and intended without question to point to the author himself. … In a larger, more impersonal context, these poems seemed to me one culmination of the Romantic and modern tendency to place the literal Self more and more at the center of the poem.

During the 1950s and 1960s Lowell became the poetic consciousness of the United States, declaiming against its descent into materialism and its waging of unjustified wars. Lowell was one of the lead speakers at the 1967 March on the Pentagon to protest the Vietnam War. Norman Mailer describes him at the March:

Lowell had the most disconcerting mixture of strength and weakness in his presence, a blending so dramatic in its visible sign of conflict that one had to assume he would be sensationally attractive to women. He had something untouchable, all insane in its force: one felt immediately that there were any number of causes for which the man would be ready to die, and for some he would fight, with an axe in his hand and a Cromwellian light in his eye. It was even possible that physically he was very strong—one couldn’t tell at all—he might be fragile, he might have the sort of farm mechanic’s strength which could manhandle the rear axle and differential off a car and into the back of a pickup. But physical strength or no, his nerves were all too apparently delicate. Obviously spoiled by everyone for years, he seemed nonetheless to need the spoiling. These nerves—the nerves of a consummate poet—were not tuned to any battering. (Mailer, 1968, pp 53-54)

Final Poems

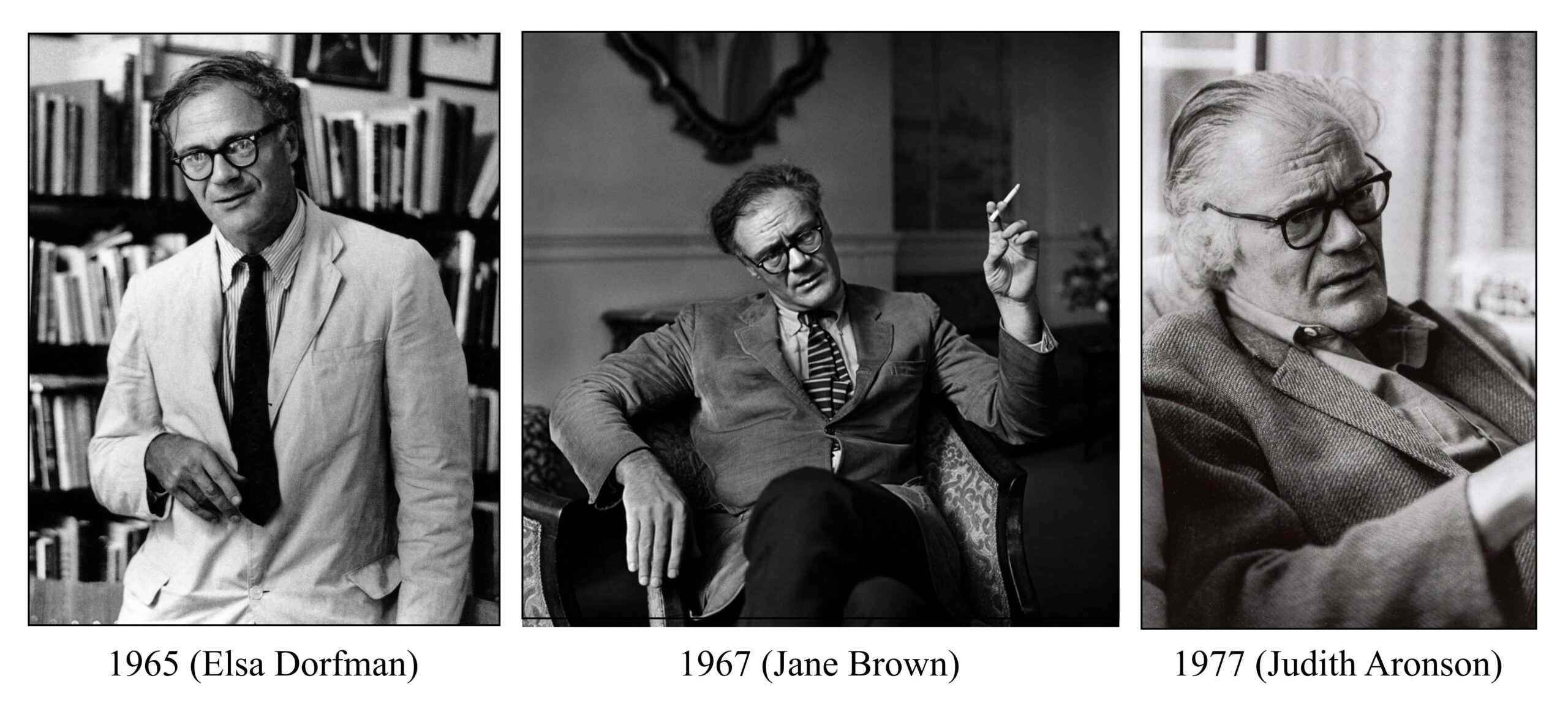

Lowell’s last book of poetry, Day by Day, came out just after his death from a sudden heart attack in 1977. The penultimate poem in that book is Thanks-Offering for Recovery:

The airy, going house grows small

tonight, and soft enough to be crumpled up

like a handkerchief in my hand.

Here with you by this hotbed of coals,

I am the homme sensuel, free

to turn my back on the lamp, and work.

Something has been taken off,

a wooden winter shadow—

goodbye nothing. I give thanks, thanks—

thanks too for this small

Brazilian ex voto, this primitive head

sent me across the Atlantic by my friend . . .

a corkweight thing,

to be offered Deo gratias

in church on recovering from head-injury or migraine—

now mercifully delivered in my hands,

though shelved awhile unnoticing and unnoticed.

Free of the unshakable terror that made me write . . .

I pick it up, a head holy and unholy,

tonsured or damaged,

with gross black charcoaled brows and stern eyes

frowning as if they had seen the splendor

times past counting . . . unspoiled,

solemn as a child is serious—

light balsa wood the color of my skin.

It is all childcraft, especially

its shallow, chiseled ears,

crudely healed scars lumped out

to listen to itself, perhaps, not knowing

it was made to be given up.

Goodbye nothing. Blockhead,

I would take you to church,

if any church would take you . . .

This winter, I thought

I was created to be given away.

Lowell is describing a small figurine from the northeastern region of Brazil, a gift from his friend Elizabeth Bishop. This was an ex voto (“from a vow”) offering, called milagré in Portuguese. Such objects, were left at a church as thanks to God after recovery from illness. A tiny leg would be left when the arthritis abated, a miniature head after the migraine had ended. The illustration on the right shows a small (4-inch) head (not the one described by Lowell). The poet wonders whether such an offering might serve as thanks now that the “unshakable terror that made me write” had finally finished.

Epilogue

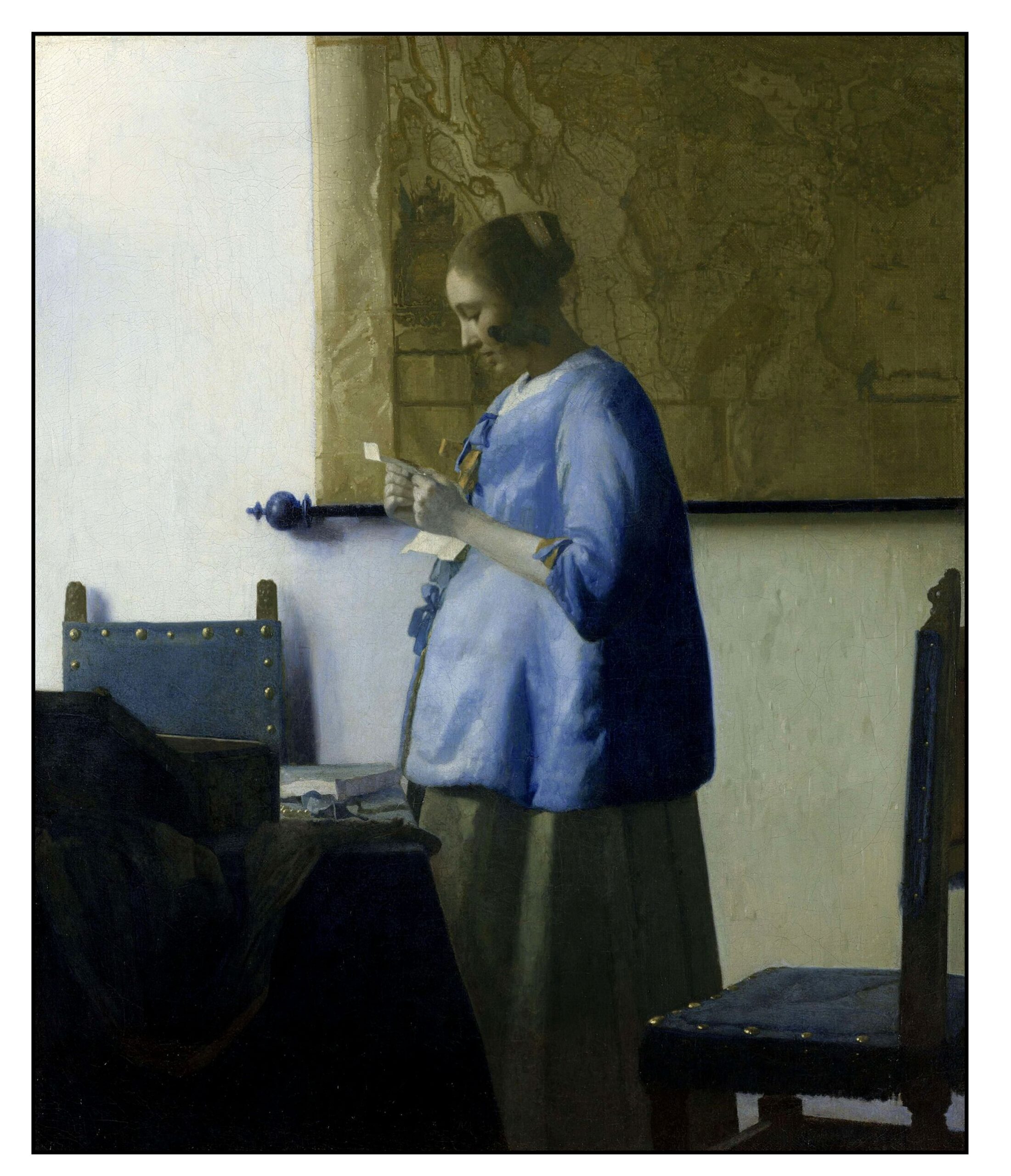

Lowell’s final poem in the book Day by Day serves as an epilogue to a life distinguished by severe madness and by significant poetry:

Those blessèd structures, plot and rhyme—

why are they no help to me now

I want to make

something imagined, not recalled?

I hear the noise of my own voice:

The painter’s vision is not a lens,

it trembles to caress the light.

But sometimes everything I write

with the threadbare art of my eye

seems a snapshot,

lurid, rapid, garish, grouped,

heightened from life,

yet paralyzed by fact.

All’s misalliance.

Yet why not say what happened?

Pray for the grace of accuracy

Vermeer gave to the sun’s illumination

stealing like the tide across a map

to his girl solid with yearning.

We are poor passing facts,

warned by that to give

each figure in the photograph

his living name.

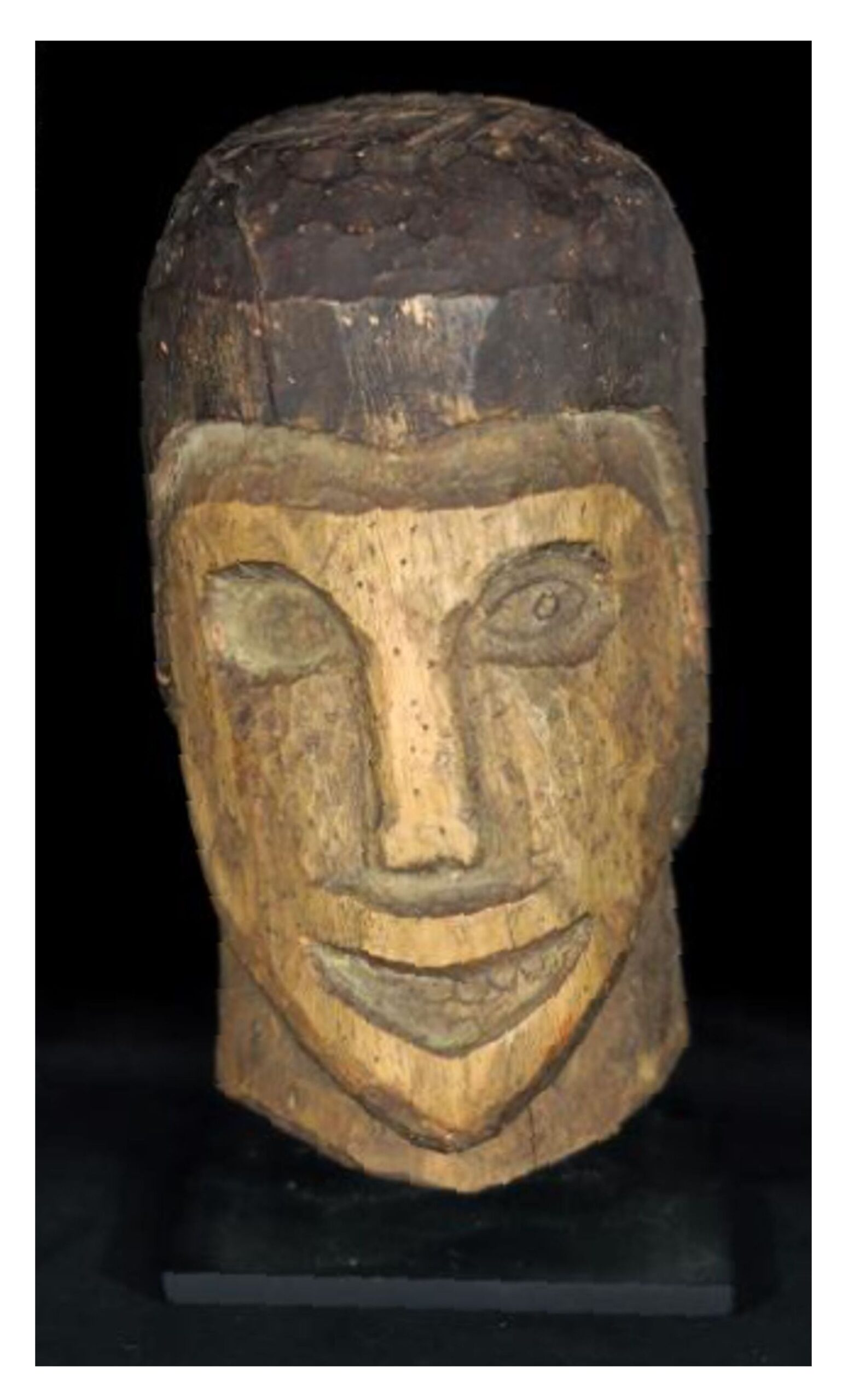

At the end of the poem Lowell refers to Vermeer’s 1662 painting Woman Reading a Letter in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum. Lowell’s prayed to be as accurate in his poetry as Vermeer in his painting. On another level, the painting embodied the tranquility that was so often missing in his life.

References

Andreasen, N. C., & Canter A. (1974). The creative writer: psychiatric symptoms and family history. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 15(2), 123-131.

Andreasen, N. C. (2008). The relationship between creativity and mood disorders. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 10 (2), 251-255.

Axelrod, S. G. (2015). Robert Lowell: Life and art. Princeton University Press.

Beam, A. (2003). Gracefully insane: the rise and fall of America’s premier mental hospital. PublicAffairs Books.

Fender, S. (1973). What really happened to Warren Winslow? Journal of American Studies, 7(2), 187–190.

Greenwood, T. A. (2020). Creativity and bipolar disorder: a shared genetic vulnerability. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16(1), 239–264.

Hamilton, I. (1982). Robert Lowell: a biography. Random House

Hass, R. (1977). Lowell’s Graveyard. Salmagundi, 37(37), 56–72.

Jamison, K. R. (2017). Robert Lowell: setting the river on fire: a study of genius, mania, and character. Alfred A. Knopf.

Lowell, R. (1946). Lord Weary’s castle. Harcourt, Brace & Co.

Lowell, R. (1977). Day by day. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Lowell, R. (edited by Bidart, F., & Gewanter, D., 2003). Collected poems. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Lowell, R. (edited by Axelrod, S. G., & Kość, G., 2022). Memoirs. Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Ludwig, A. M. (1995). The price of greatness: resolving the creativity and madness controversy. Guilford Press.

Mailer, N. (1968). The armies of the night; history as a novel, the novel as history. New American Library.

Mann, T. (translated by Neugroschel, J., 1998). Death in Venice and other tales. Viking.

McConahay, M. D. (1986). ‘Heidelberry braids’ and Yankee “politesse”: Jean Stafford and Robert Lowell reconsidered. Virginia Quarterly Review, 62(2), 213-236.

Remaley, P. P. (1976). The quest for grace in Robert Lowell’s “Lord Weary’s Castle.” Renascence, 28(3), 115–122.

Rosenthal, M. L. (1967). Robert Lowell and ‘Confessional’ Poetry. In Rosenthal, M. L. The New Poets: American and British Poetry Since World War II, Oxford University Press, pp. 25-78.

Leave a Reply