Robinson Jeffers (1887-1962) was an American poet who celebrated the beauty of California’s coast. In 1914 he and his wife Una settled in Carmel. In 1919 Jeffers and his family moved into Tor House, a home that he and a stone-mason had built on Carmel Point using rocks from the shore. From 1920 to 1924 he built by himself the adjacent Hawk Tower. Jeffers became famous soon after the publication of Tamar and Other Poems in 1924. This book and those that followed included both long narratives and shorter lyrics. His epics were bloody and tragic; his verse was free and passionate. Underlying his poems was an austere philosophy of “inhumanism.” This compared the transience of humanity to the persistence of the natural world, and proposed that we should detach ourselves from the passions of mankind and simply celebrate the beauty of the universe. Over the next decade, Jeffers published extensively and in 1932 his photograph graced the cover of Time. After World War II, his outrage at the death and destruction that occurred during the war and the severity of his inhumanist philosophy led to controversy and obscurity. In more recent years, the environmental movement has found inspiration in his love of the natural world and his anger about how humanity has despoiled it.

Early Life

John Robinson Jeffers was born in 1887 in Allegheny, Pennsylvania. His father was a Presbyterian minister and a Professor of Ancient Languages at the Western Theological Seminary. It was his father’s second marriage, and his son’s middle name, which he preferred, was in honor of the first wife, who had died five years earlier. Robinson Jeffers attended private schools in Pittsburgh, and then in Germany and Switzerland. He was a bright student and by the time he was 16 he was fluent in Latin, Greek, French and German. In 1903, his father turned 65 years old and retired to live in Los Angeles.

After graduating from Occidental College in 1905, Jeffers was unsure of what he wanted to do.. He studied languages at the University of Southern California for a year, but then switched to Medicine. After 3 years, he decided that he did not wish to be a physician and began studies in Forestry at the University of Seattle. He found the curriculum too business-oriented and quit, returning to Los Angeles in 1910.

While at the University of Southern California in 1906, Jeffers met Una Call Kuster (1884-1950) who was also studying languages (Greenan, 1988). At the age of 18 years, she had married Edward Kuster, a rich lawyer and socialite, but wished to complete her education before having a family. Over the years Robinson and Una become fast friends and then passionate lovers. By 1910, their affair became widely known, and divorce proceedings were initiated. These events may have contributed to Jeffers’s moving to Seattle to study forestry. The following illustration shows photographs from 1911 (adapted from Karman, 1913).

After the divorce was finalized in 1913, Robinson and Una were married. Their first two years together were marked by grief. A daughter was born in early 1914 but only lived a day. The couple then moved to Carmel, a small village just south of the Monterey peninsula, to be alone together. Then Robinson’s father died in December, 1914.

In 1912, Jeffers had published at his own expense a book of poems – Flagons and Apples. Of the 500 copies printed, 480 were remaindered and sold to a second-hand bookstore. Now in Carmel, inspired by the Big Sur country just south of the village, Jeffers put together a new book of poems – The Californians – that was published by Macmillan in 1916. This book contained poems of many forms and lengths, most using classical rhythms and rhyme-schemes.

Twin boys – Garth and Donnan – were born in 1916, and the Jeffers slowly settled into their life at Carmel. When the United States entered the war in 1917, Jeffers attempted to join the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps but his application was rejected because he was already 30 years old and responsible for a new family. Jeffers attempted to write a long poem about the war but it came to nothing. In 1920 he submitted some new poems to Macmillan, but The Californians had not sold well and the publisher rejected his submission (Zaller, 1991).

Tor House and Hawk Tower

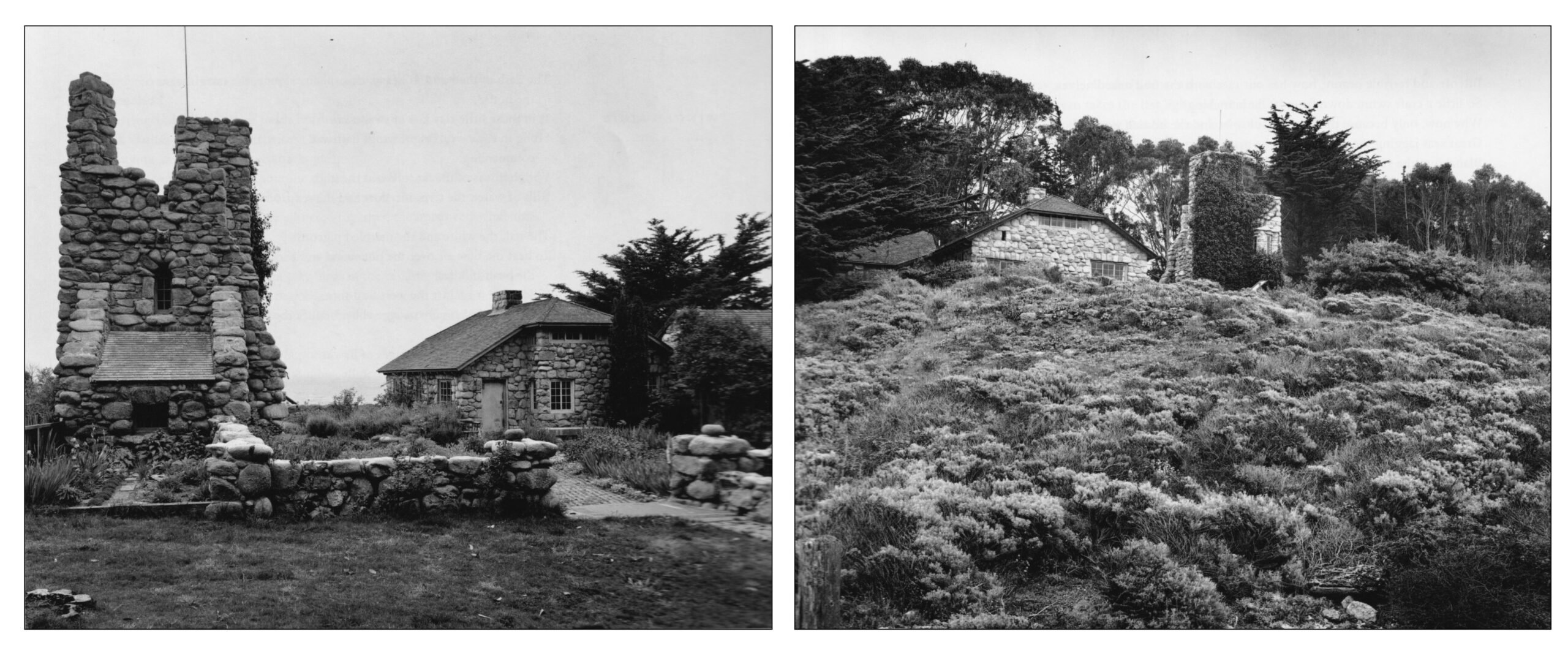

In 1919 Jeffers purchased land out on Carmel Point, a raised area jutting out into the ocean just south of Carmel Beach. Here Jeffers helped a stonemason to build Tor House using the rocks and boulders on the point and the adjacent beach. The name comes from the Gaelic word for hill or rocky outcrop. After the house was finished, Jeffers built the adjacent Hawk Tower by himself over several years. The following photographs by Morley Baer show views of the house and tower (from the land and from the sea) as it was in 1964 (Jeffers, Baer & Karman, 2001 At that time everything was still open to the sea; now other houses encroach upon the site.

Working on the house and the tower freed up Jeffers’s mind and released his creative impulses. Jeffers stopped using rhyme, and decided to write with natural rhythms in the style of Walt Whitman. Line length became a structuring device for his new poems, which often used alternating long and short lines (Hymes, 1991). The long lines have a grandeur but make the poems difficult to print upon either page or screen. In the books he was to publish in this style, the longer lines are broken in two. For this posting some of the poems will be printed in a smaller font than the rest of the text. These new characteristics are present his poem about Tor House (published in 1928):

If you should look for this place after a handful of lifetimes:

Perhaps of my planted forest a few

May stand yet, dark-leaved Australians or the coast cypress, haggard

With storm-drift; but fire and the axe are devils.

Look for foundations of sea-worn granite, my fingers had the art

To make stone love stone, you will find some remnant.

But if you should look in your idleness after ten thousand years:

It is the granite knoll on the granite

And lava tongue in the midst of the bay, by the mouth of the Carmel

River-valley, these four will remain

In the change of names. You will know it by the wild sea-fragrance of wind

Though the ocean may have climbed or retired a little;

You will know it by the valley inland that our sun and our moon were born from

Before the poles changed; and Orion in December

Evenings was strung in the throat of the valley like a lamp-lighted bridge.

Come in the morning you will see white gulls

Weaving a dance over blue water, the wane of the moon

Their dance-companion, a ghost walking

By daylight, but wider and whiter than any bird in the world.

My ghost you needn’t look for; it is probably

Here, but a dark one, deep in the granite, not dancing on wind

With the mad wings and the day moon. (CP I, 408)

(The references for this and for subsequent poems in this posting are to Jeffers’s Collected Poems edited by Tim Hunt).

Tamar

Jeffers’s first collection of poems after moving to Tor House – Tamar and Other Poems (1924), published at his own expense – was written in his new free verse. The epic poem Tamar tells the tragedy of a family living at Point Lobos just south of Carmel. The tale has biblical echoes in the stories of Tamar who seduced her father-in-law Judah (Genesis 38), and of her namesake Tamar, the daughter of King David, who was raped by her step-brother Amnon (2 Samuel 13). The following is a summary of Jeffers’s poem (from Karman, 2015, pp 55-56);

Tamar … tells the story of the doomed Cauldwells who live in an isolated home on Point Lobos, south of Carmel. The head of the house is David Cauldwell, an old, broken-down man who frequently quotes the Bible. Two children, a son named Lee and a daughter Tamar, live with him, along with his demented sister Jinny, and Stella Moreland, the sister of his dead wife Lily. The action of the story, set around the time of America’s entry into World War I, concerns Tamar’s incestuous relationship with her brother, an ensuing pregnancy, and her seduction of an unloved suitor to snare a respectable father for the child. Through her Aunt Stella, a medium for the dead, Tamar learns that her father had an incestuous relationship with his sister Helen, which makes her behavior seem more like the simple repetition of a family pattern instead of the singular act of a bounds-breaking free spirit. In the process of coming to terms with this knowledge, Tamar dances naked in a trance-induced frenzy on the seashore, where she is violated by the ghosts of Indians who once lived on Point Lobos, and where she speaks with the ghost of her Aunt Helen, her father’s sister-lover. As Tamar’s mind sickens, she thinks of ways to destroy her family, especially after learning that her brother, seeking adventure, plans to enlist and leave home. The end comes in a wild conflagration. On the eve of her brother’s departure, with her benighted suitor at hand, Tamar orchestrates an explosion of jealous rage. As her brother pulls a knife and stabs her suitor, Tamar’s Aunt Jinny sets the house on fire. Floors break, walls fall, and everyone perishes in the flames.

Jeffers tells his convoluted story of incest and murder in an epic style, and intersperses the events with quieter descriptions of the California Coast. This combination of the lurid and the lyrical makes for uneasy reading. Not a poem for the faint of heart, it was the first of many long narratives that Jeffers was to write over the next decades.

The book also contains many short poems describing the beauty of the California Coast, such as Divinely Superfluous Beauty:

The storm-dances of gulls, the barking game of seals,

Over and under the ocean…

Divinely superfluous beauty

Rules the games, presides over destinies, makes trees grow

And hills tower, waves fall.

The incredible beauty of joy

Stars with fire the joining of lips, O let our loves too

Be joined, there is not a maiden

Burns and thirsts for love

More than my blood for you, by the shore of seals while the wings

Weave like a web in the air

Divinely superfluous beauty.(CP I, 4)

Jeffers also began to consider the transience of humanity in a universe that lasts for ever in such poems as To the Stone-Cutters (recorded by Jeffers in 1941):

Stone-cutters fighting time with marble, you foredefeated

Challengers of oblivion

Eat cynical earnings, knowing rock splits, records fall down,

The square-limbed Roman letters

Scale in the thaws, wear in the rain. The poet as well

Builds his monument mockingly;

For man will be blotted out, the blithe earth die, the brave sun

Die blind and blacken to the heart:

Yet stones have stood for a thousand years, and pained thoughts found

The honey of peace in old poems. (CP I, 5)

Big Sur

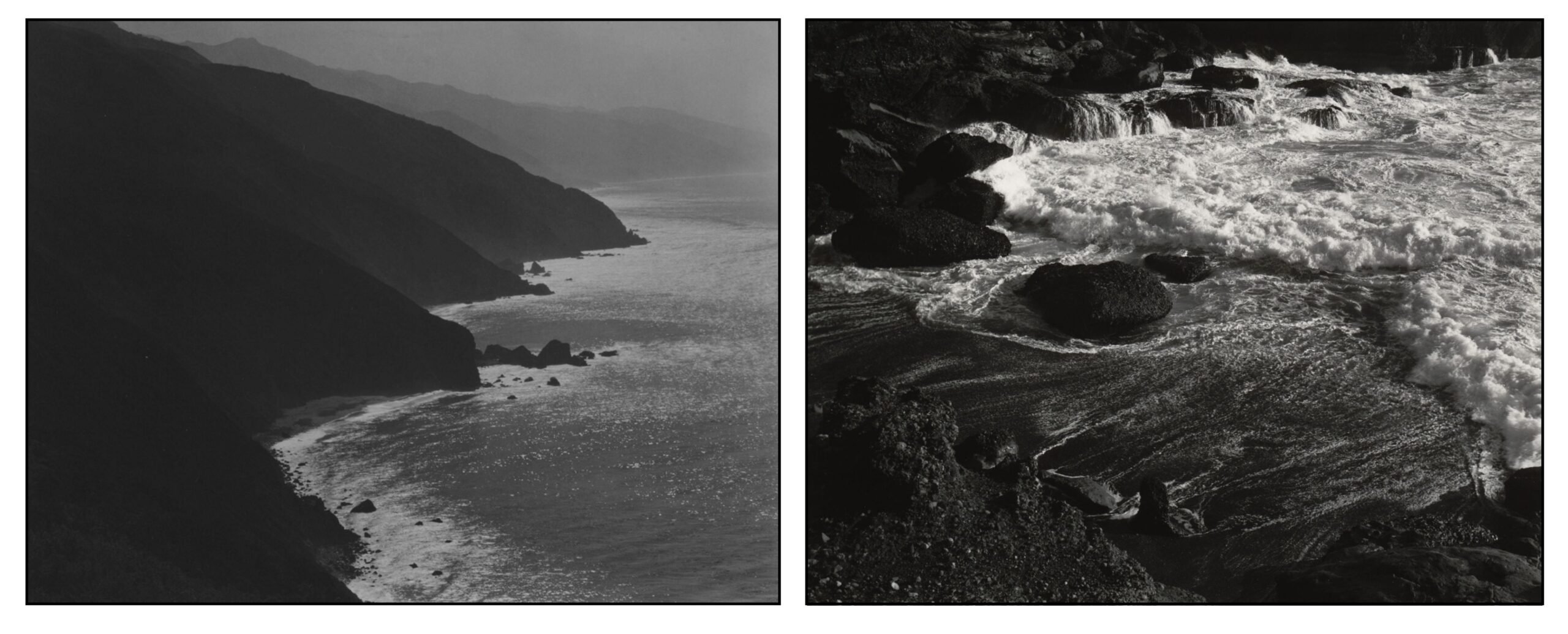

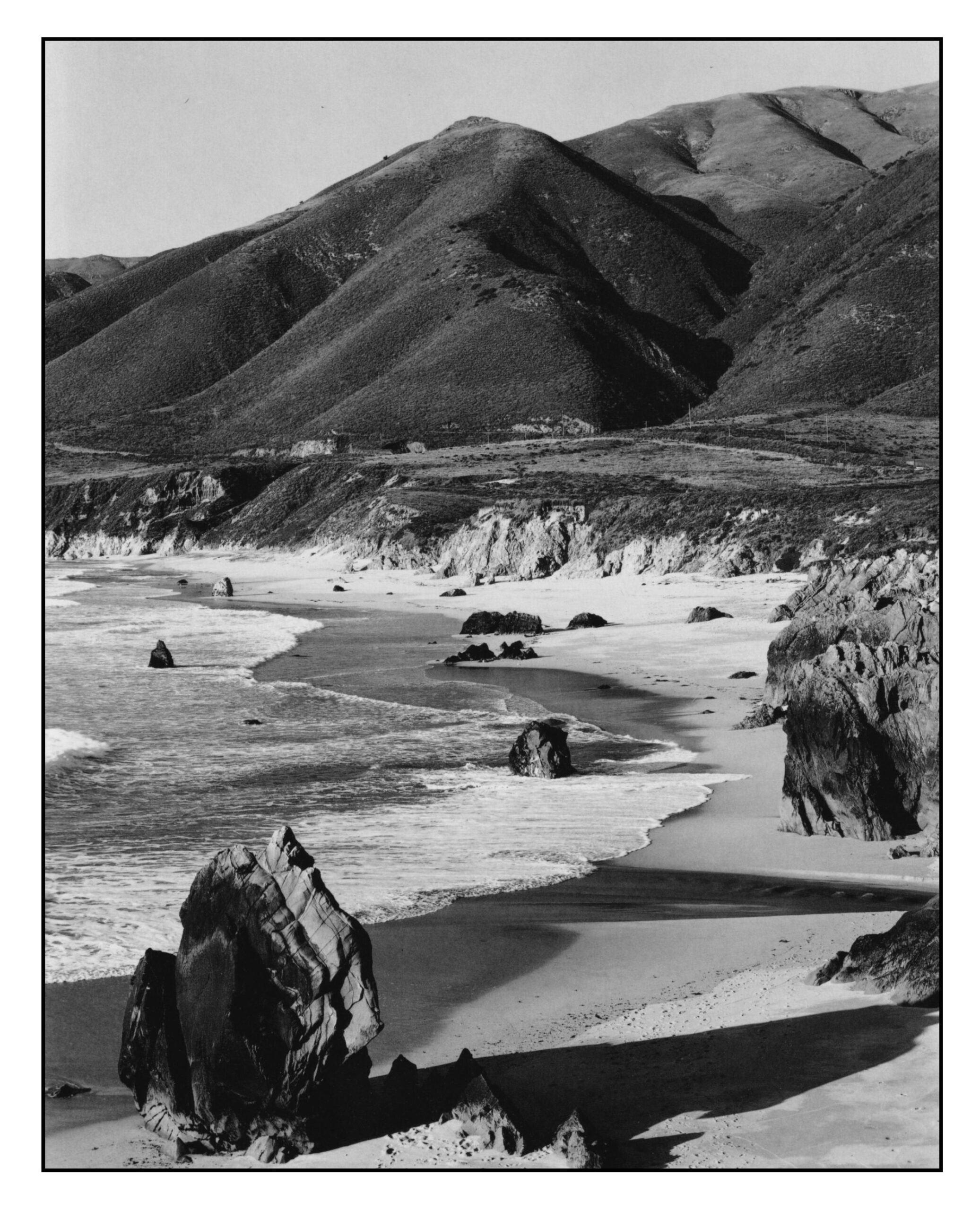

The California coast south of Carmel and north of San Simeon is known as the Big Sur – a name deriving from the Spanish el sur grande (the big south), which is how the Spanish settlers on the Monterey Peninsula referred to the region. Here the Santa Lucia mountains rise directly from the sea. Edward Weston (1886-1958) took many striking photographs of this coastline, and in 1938 moved his studio to Carmel. Below are Weston’s photographs from 1929 and 1938.

The poetry of Robinson Jeffers celebrated the beauty of Big Sur. The following is a poem about Garapata Beach where Soberanes (or Sovranes) Creek empties into the Pacific – The Place for No Story (1932). When introducing the poem in a reading in 1941 Jeffers remarked about the title:

These eleven lines are called “The Place for No Story,” because the coast here, its pure and simple grandeur, seemed to me too beautiful to be the scene of any narrative of mine. (Jeffers, 1956)

The coast hills at Sovranes Creek;

No trees, but dark scant pasture drawn thin

Over rock shaped like flame;

The old ocean at the land’s foot, the vast

Gray extension beyond the long white violence;

A herd of cows and the bull

Far distant, hardly apparent up the dark slope;

And the gray air haunted with hawks:

This place is the noblest thing I have ever seen. No imaginable

Human presence here could do anything

But dilute the lonely self-watchful passion. (CP II, 157)

The following it is a 1964 photograph of the beach by Morley Baer (Jeffers, Baer & Karman, 2001). Barely visible in the photograph are hawks, haunting the sky above the further slopes:

The poem is “an evocation of the sublime” (Zaller, 2012, p 171). Yet it differs from Wordsworth’s sublime. It is not the participation of the individual human consciousness in something universal:

…a sense sublime,

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

(Lines Composed a Few Miles above Tintern Abbey, 1798)

For Jeffers, the sublime is totally independent of any human interaction. It is something to be wondered at but not participated in.

Fame

After Tamar, Jeffers became very successful, publishing a book every year or two. Like Tamar, these books contained both long narratives and short lyrics. His poetic style – the long lines and the free rhythms – did not change. The narrative poems continued to be full of sex and violence – like penny-dreadfuls updated to the 20th Century and translated into poetry. Jeffers, however, had tapped some current in the American soul.

The shorter poems continued to be more approachable. The following is Hawk and Rock (1935). Robert Hass (1987) was to use this as the title poem for a later collection of Jeffers’s shorter lyrics.

Here is a symbol in which

Many high tragic thoughts

Watch their own eyes.

This gray rock, standing tall

On the headland, where the sea-wind

Lets no tree grow,

Earthquake-proved, and signatured

By ages of storms: on its peak

A falcon has perched.

I think, here is your emblem

To hang in the future sky;

Not the cross, not the hive,

But this; bright power, dark peace;

Fierce consciousness joined with final

Disinterestedness;

Life with calm death; the falcon’s

Realist eyes and act

Married to the massive

Mysticism of stone,

Which failure cannot cast down

Nor success make proud. (CP II, 416)

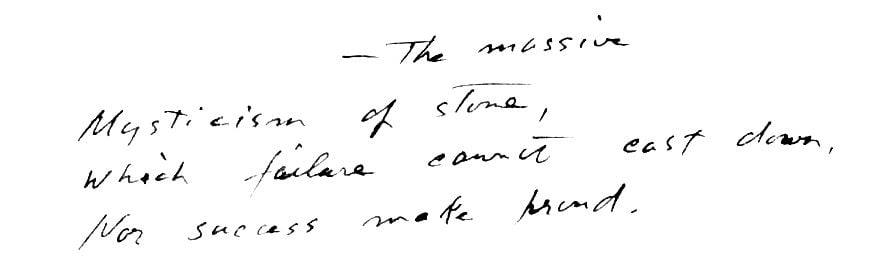

The poem proclaims Jeffers outlook on life – a combination of fierce consciousness and disinterestedness, bright power and dark peace. The following shows the final lines in Jeffers’s handwriting (from an inscription in a book gifted to a friend).

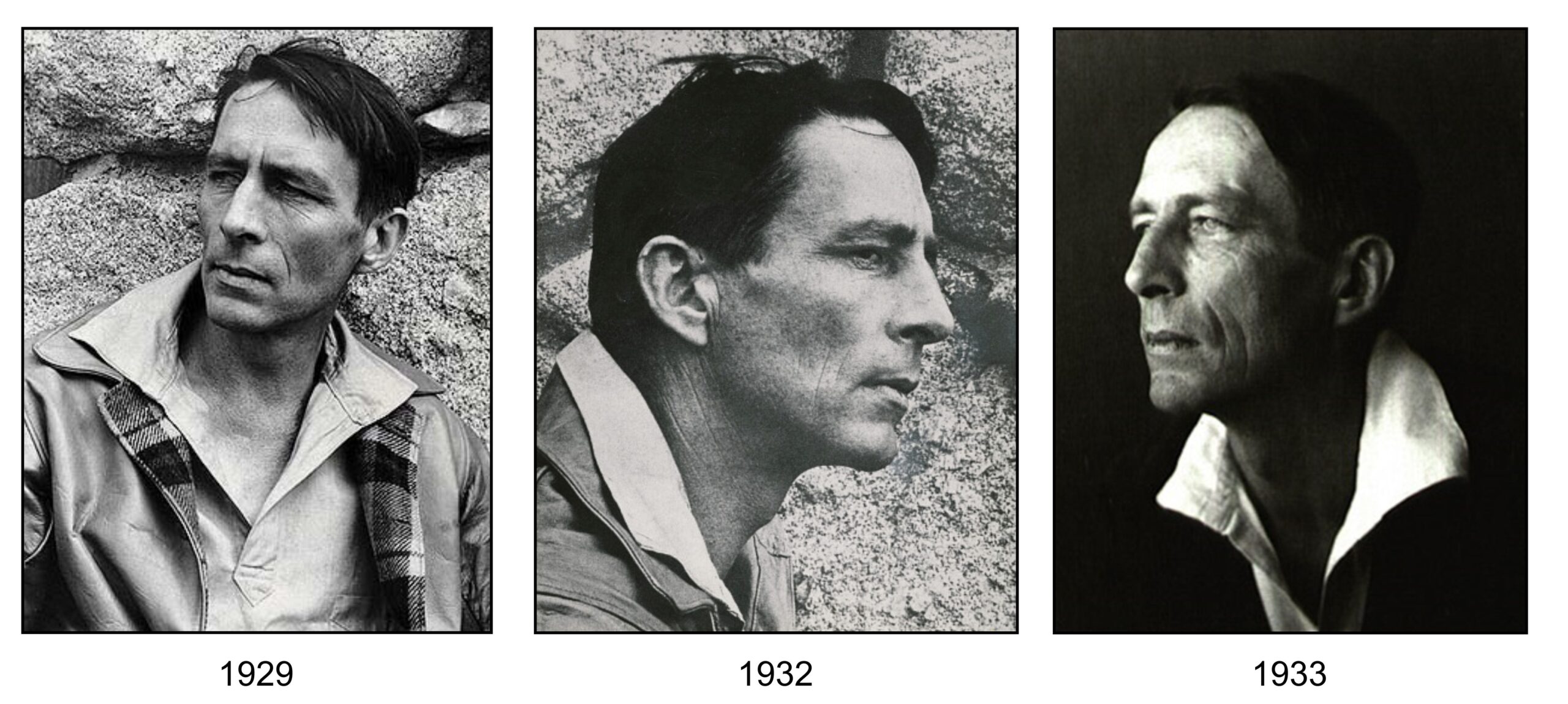

Jeffers’s photograph made the cover of Time in 1932. (It was not until 1950 that the magazine awarded a cover portrait to either Robert Frost or T. S. Eliot.) In 1938, Random House published The Selected Poetry of Robinson Jeffers, a volume of over 600 pages. The following are photographs of Jeffers taken by Edward Weston during the height of his fame – the middle image is from the cover of Time:

Inhumanism

Jeffers had received a modern scientific education and understood the import of evolutionary theory and recent findings in astronomy upon our place in the world and in time. He realized that the human species might develop further, but would ultimately become extinct, the universe then continuing to exist without any further contribution from mankind. Nevertheless, he gloried in the heart-breaking beauty of the natural world. He described this “religious feeling” in his 1941 talk to the Library of Congress (Jeffers, 1956, pp 23-24):

It is the feeling … I will say the certitude … that the world, the universe is one being, a single organism, one great life that includes all life and all things; and is so beautiful that it must be love and reverenced; and in moments of mystical vision we identify ourselves with it.

But these moments are evanescent. The beauty of the world will outlast us. The following are the lines that end his 1926 poem Credo:

The beauty of things was born before eyes and sufficient to itself; the heart-breaking beauty

Will remain when there is no heart to break for it. (CP I, 239)

Jeffers view of beauty was that it was part of nature and would outlast the perceiver. An opposing view is that beauty is in the mind, and that human beings have evolved to find the world they live in beautiful. Such a development facilitates human survival: if we cherish the world, we will reap its bounty.

Jeffers’s philosophy was more specifically described in the preface to his 1947 book The Double Axe (the original version of which is included in his 2001 Selected Poetry edited by Tim Hunt):

It is based on a recognition of the astonishing beauty of things and their living wholeness, and on a rational acceptance of the fact that mankind is neither central nor important in the universe; our vices and blazing crimes are as insignificant as our happiness. We know this, of course, but it does not appear that any previous one of the ten thousand religions and philosophies has realized it. An infant feels himself to be central and of primary importance; an adult knows better; it seems time that the human race attained to an adult habit of thought in this regard. The attitude is neither misanthropic nor pessimist nor irreligious, though two or three people have said so, and may again; but it involves a certain detachment.

Jeffers contrasted his ideas to Renaissance Humanism, which, though he preferred it to the preceding Scholastic Theology, he felt improperly placed Man at the center of the universe. The Renaissance took to heart wisdom of philosophers such as Protagoras of Abdera who proposed that “Man is the measure of all things” and doubted the existence of the gods: “Concerning the gods, I have no means of knowing whether they exist or not, nor of what sort they may be, because of the obscurity of the subject, and the brevity of human life.” (Bonazzi, 2020). Renaissance philosophers like Pico della Mirandola focussed on the man rather than on God. In his Oration on the Dignity of Man, he proclaimed that “There is nothing to be seen more wonderful than Man” (Forbes, 1942).

Jeffers called his philosophy “inhumanism” to distinguish it from the humanism of the Renaissance (Carpenter, 1981). As Nafis-Sahely (2016) has remarked, the philosophy “might have fared better under a different name.” Perhaps, for example, “naturalism.” The first meaning suggested by the word “inhumanism” is “brutality.” Jeffers’s inhumanism is an austere and detached view of the world. It has many similarities to stoicism (Lioi, 2025): we live our life as best we can; we pass away and the world persists. In his 1941 talk, Jeffers (1956, p 28) related his inhumanism to the main tenets of Christianity:

It seems to me, analogously, that the whole human race spends too much emotion on itself. The happiest and freest man is the scientist investigating nature, or the artist admiring it; the person who is interested in things that are not human. Or if he is interested in human things, let him regard them objectively, as a small part of the great music. Certainly humanity has claims, on all of us; we can best fulfill them by keeping our emotional sanity; and this by seeing beyond and around the human race. This is far from humanism; but it is, in fact, the Christian attitude: … to love God with all one’s heart and soul, and one’s neighbor as one’s self — as much as that, but as little as that.

Jeffers was enthusiastic in his love of nature, but far more detached in his love of neighbor. Although he wrote in the style of Walt Whitman, he lacked that poet’s intense love of his fellow man.

One of the clearest poetic descriptions of inhumanism is in final section of the late poem De Rerum Virtute or (On the Nature of Virtue) (1954, discussed extensively by Chapman, 2002):

One light is left us: the beauty of things, not men;

The immense beauty of the world, not the human world.

Look—and without imagination, desire nor dream—directly

At the mountains and sea. Are they not beautiful?

These plunging promontories and flame-shaped peaks

Stopping the sombre stupendous glory, the storm-fed ocean?

Look at the Lobos Rocks off the shore,

With foam flying at their flanks, and the long sea-lions

Couching on them. Look at the gulls on the cliff-wind,

And the soaring hawk under the cloud-stream—

But in the sage-brush desert, all one sun-stricken

Color of dust, or in the reeking tropical rain-forest,

Or in the intolerant north and high thrones of ice—is the earth not beautiful?

Nor the great skies over the earth?

The beauty of things means virtue and value in them.

It is in the beholder’s eye, not the world? Certainly.

It is the human mind’s translation of the transhuman

Intrinsic glory. It means that the world is sound,

Whatever the sick microbe does. But he too is part of it. (CP III, 403)

The Double Axe

Jeffers was thoroughly dismayed by World War II and believed that the United States should never have entered the fighting. His pacifism was accentuated by the fact that his son Garth was serving in the US forces. Donnan had been excused because of a heart murmur. Jeffers could not see any difference between the sides – he thought that Churchill and Roosevelt were as guilty as Hitler and Mussolini.

In 1948 Jeffers published his first collection of poems since Pearl Harbor – The Double Axe. The The title poem was composed of two parts: The Love and the Hate and The Inhumanist. In the first part a young soldier killed in the Pacific Campaign wills his decaying body to return home to the family ranch in the Big Sur and confront his father:

Did you

And your old buddies decide what the war’s about?

I came to ask. You were all for it, you know;

And keeping safe away from it, so to speak, maybe you see

Reasons that we who only die in it can’t, (CP III, 222)

The second part of the poem occurs years later on the same Big Sur ranch. Its caretaker (and possessor of the double-bit axe) looks after the homestead as various refugees from a nuclear war arrive. After a snowfall the old man addresses his axe to repudiate the humanism of the Renaissance:

Man is no measure of anything. Truly it is yours to hack, snow’s to be white, mine to admire;

Each cat mind her own kitten: that is our morals. But wait till the moon comes up the snow-tops,

And you’ll sing Holy. (CP III, 264)

Jeffers’s politics and philosophy did not appeal to a people that considered the war they had just won as righteous. The publisher convinced Jeffers to withdraw some of his most virulent anti-war poems (Shebl, 1976) and added a disclaimer to the book in a “Publisher’s Note”:

Random House feels compelled to go on record with its disagreement over some of the political views pronounced by the poet in this volume.

The reviews were scathing. From then on, Jeffers was no longer an acclaimed poet. He lived out the rest of his life in Carmel in relative obscurity. He continued to publish occasionally but critics disparaged his work even while admitting its importantance. The following is from a review of his posthumously published last poems:

Surely he provides us with plenty to carp about: his oracular moralizing, his cruel and thoroughly repellent sexuality, his dreadful lapses of taste when he seems simply to throw back his head and howl, his slovenly diction, the eternal sameness of his themes, the amorphous sprawl of his poems on the page. The sheer power and drama of some of Jeffers’ writing, however, still carries the day despite everything, and this is not so much because of the presence of the Truth that Jeffers believes he has got hold of but because of what might be called the embodiment of that Truth: Jeffers’ gorgeous panorama of big imagery, his galaxies, suns, seas, cliffs, continents, mountains, rivers, flocks of birds, gigantic schools of fish, and so on. His Truth is hard to swallow try looking at your children and drawing comfort from Jeffers’ “inhumanism”—but one cannot shake off Jeffers’ vision as one can the carefully prepared surprises of many of the neatly packaged stanzas we call “good poems”; it is too deeply disturbing and too powerfully stated. (Dickey, 1964).

In the late 60s the escalation of the Vietnam War led to the involvement and death of US troops. Jeffers’s passionate pacificism became more understandable, and his poetry underwent some rehabilitation and republication (Nolte, 1978).

The Environmental Movement

Another important development affecting the reputation of Robinson Jeffers was the birth of the modern environmental movement with the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring in 1962. As well as pointing out the severe problems that result from our misuse of the environment, the movement also published books showing the beauty of unspoiled nature. A major example of this was the book Not Man Apart (Adams et al, 1964) which combined photographs of the Big Sur Coast with lines from Robinson Jeffers.

Karman (2015) remarks about Jeffers attitude to man’s place in nature:

Jeffers’ experience of deep time added a vatic amplitude to his verse, and a sharp moral edge. He spoke repeatedly about the destruction of Earth’s environment, warning, shrilly at times, of the effects of overpopulation, pollution, and the exploitation of natural resources.

Quigley (2002) places Jeffers in a direct line between Thoreau (1817-1862) and later authors such as Edward Abbey (1927-1989) and Gary Snyder (1930- ) in the development of modern environmentalism. Of these writers, Jeffers was the most critical of how man has misused the world, and perhaps the most pessimistic. However, Abbey, Snyder and other writers have taken to heart his criticisms and tried to formulate new and better ways for man and nature to interact. Wyatt (1986) has written of the affinity between Jeffers and Snyder, both of whom spent much time building homes to fit in with the natural world. John Elder (1985) discussed Jeffers and nature in the context of how nature and humanity must interact – a process that he terms “culture:”

In learning to find equivalence between mountains, grass, and man, we gain the composure of a larger design. It is not a fixed, symmetrical rose, like Dante’s covering order, but rather a process of tidal exchange, of decay and renewal. Only as we learn to see it in a natural order beyond man’s civilized system may the human waste-land be redeemed and the individual made whole. Conversely, unless the city is restored and human life brought back into physical and spiritual balance, the wilderness beloved of fierce solitaries like Jeffers will inevitably be destroyed. The circuit of mutual dependence between nature and civilization defines my understanding of the word culture: it is a process rather than a product, something that grows rather than being manufactured. And only in poetry is culture fully realized.</p>

In Retrospect

Jeffers wrote some powerful but difficult longer poems and some fine shorter lyrics. I would like to end the posting with one of his early poems – The Excesses of God (1924) – together with the engraving by Malette Dean that accompanies the poem in his 1956 book:

Is it not by his high superfluousness we know

Our God? For to equal a need

Is natural, animal, mineral: but to fling

Rainbows over the rain

And beauty above the moon, and secret rainbows

On the domes of deep sea-shells,

And make the necessary embrace of breeding

Beautiful also as fire,

Not even the weeds to multiply without blossom

Nor the birds without music:

There is the great humaneness at the heart of things,

The extravagant kindness, the fountain

Humanity can understand, and would flow likewise

If power and desire were perch-mates.(CP I, 4)

Resources

The website of the Robinson Jeffers Association provides links to many different resources about the poet, including an archive of most of the issues of the journal Jeffers Studies.

References

Adams, A., Jeffers, R., & Brower, D. (1965). Not man apart: Lines from Robinson Jeffers with photographs of the Big Sur Coast. Sierra Club.

Bonazzi, M. (2020). Protagoras. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Carpenter, F. I. (1981). The inhumanism of Robinson Jeffers. Western American Literature, 16(1), 19-25

Chapman, S. (2002). De Rerum Virtute: a critical anatomy. Jeffers Studies, 6(4), 22-35.

Dickey, J. (1964). Review of The Beginning and the End and Other Poems. Poetry, 103(5), 316-324.

Elder, J. (1985). Imagining the Earth: poetry and the vision of nature. University of Illinois Press.

Forbes, E. L. (1942). Of the Dignity of Man: Oration of Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, Count of Concordia. Journal of the History of Ideas, 3(3), 347-354.

Greenan, E. (1998). Of Una Jeffers. Story Line Press.

Hass, R. (1987). Robinson Jeffers: the poetry and the life. The American Poetry Review. 16(6), 33-41. (a reprint of the introduction to Rock and Hawk: A Selection of Shorter Poems by Robinson Jeffers)

Hymes, D. (1991). Jeffers’ artistry of line. In Zaller, R. (Ed.) Centennial essays for Robinson Jeffers. (pp. 226-267). University of Delaware Press.

Jeffers, R. (1938). The selected poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Random House.

Jeffers, R. (1956). Themes in my poems. Book Club of California.

Jeffers, R. (Ed. Hunt, T., 2001). The selected poetry of Robinson Jeffers. Stanford University Press.

Jeffers, R. (Ed. Hunt, T., 1988-2002). The collected poetry of Robinson Jeffers. (5 volumes). Stanford University Press.

Jeffers, R. (Ed. Karman, J., 2009-2015). The collected letters of Robinson Jeffers: with selected letters of Una Jeffers. (3 volumes) Stanford University Press.

Jeffers, R., Baer, M., & Karman, J. (2001). Stones of the Sur. Stanford University Press.

Karman, J. (2015). Robinson Jeffers: poet and prophet. Stanford University Press.

Lioi, A. (2016). Knocking our heads to pieces against the night: going cosmic with Robinson Jeffers. In Tangney, S. (Ed.) The wild that attracts us: new critical essays on Robinson Jeffers. (pp 117-140). University of New Mexico Press.

Nafis-Sahely, A. (2016). If you believe that you’ll believe anything – Robinson Jeffers: Poet and Prophet. Wild Court.

Nolte, W. H. (1978). Robinson Jeffers redivivus. The Georgia Review, 32(2), 429-434.

Quigley, P. (2002) Carrying the weight: Jeffers’s Role in preparing the way for ecocriticism. Jeffers Studies, 6(4), 46-68.

Shebl, J. M. (1976). In this wild water: the suppressed poems of Robinson Jeffers. Ward Ritchie Press.

Wyatt, D. (1986). Jeffers, Snyder, and the ended world. In The Fall into Eden. (pp. 174–205). Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, R. (1991). Robinson Jeffers, American poetry and a thousand years. In Zaller, R. (Ed.) Centennial essays for Robinson Jeffers. (pp. 29-43). University of Delaware Press.

Zaller, R. (2012). Robinson Jeffers and the American sublime. Stanford University Press.

</pstyle=”padding-left:100px;”>

Leave a Reply