A blog for the season. One of the most vivid and intriguing Christmas stories concerns the visit of the Magi from the East:

Now when Jesus was born in Bethlehem of Judaea in the days of Herod the king, behold, there came wise men from the east to Jerusalem,

Saying, Where is he that is born King of the Jews? for we have seen his star in the east, and are come to worship him. (Matthew 2: 1-2)

In 1461 Benozzo Gozzoli completed a sequence of frescos depicting the Journey of the Magi for the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence. Illustrated below is the first of these paintings. A crowd of important people follow the Magi toward Bethlehem. At their head can be recognized the great lords of Florence, Sforza and Rimini. Among the crowd are diplomats and scholars from the Byzantine Empire (see previous blog). Indeed, one of the Magi is thought to represent the Emperor John VII Palaeologus. The painting commemorates the Council of Florence (1439), when representatives of the Eastern and Roman Churches had met in an unsuccessful attempt to reconcile their doctrinal differences. The Byzantine visitors were probably as exotic to the Italians of the 15th century as the Magi were to the Jews of the first.

About two centuries later, in 1622, Lancelot Andrewes preached a sermon on the Nativity before King James I of England. He took as his text the first two verses of the second chapter of Matthew’s gospel. He made four observations about their journey:

- This was nothing pleasant, for through deserts, all the way waste and desolate.

- Nor secondly, easy neither; for over the rocks and crags of both Arabias, specially Petra, their journey lay.

- Yet if safe – but it was not, but exceeding dangerous, as lying through the midst of the “black tents of Kedar,” a nation of thieves and cut-throats; to pass over the hills of robbers, infamous then, and infamous to this day. No passing without great troop

- Last we consider the time of their coming, the season of the year. It was no summer progress. A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off, in solsitio brumali, “the very dead of winter.” [solsitio brumali is the winter solstice – the longest day of the year]

In 1927, two centuries after that sermon, T. S. Eliot began his poem on the Journey of the Magi with a quotation from Andrewes’ sermon:

‘A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

Eliot’s 1947 reading of the whole poem:

An earlier recording for the BBC from 1942 is available at the Poetry Archive together with the full text of the poem.

Extensive annotations on the poem are available at the site of Jim Wohlpart.

The words of Andrewes that begin the poem were slightly altered. Most particularly “they” was changed to “we.” Eliot’s poem is a dramatic monologue. The speaker is one of the Magi. Many years after the journey, he remembers what it was like and how it affected him.

These initial lines are like a musical theme that a composer quotes from an earlier work as a basis for new variations. Eliot described this process is an earlier essay on an obscure Jacobean playwright:

Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different than that from which it is torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.

After expounding on the difficulties of the journey (the variations on Andrewes’ theme), the Magus consider whether the journey was worth it. He realizes the problems posed by the Nativity but finds no solution:

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

The repeated phrase “set down this” comes from Andrewes’ sermon though the other words are Eliot’s.

As well as imagining the thoughts of the Magus, Eliot was portraying his own state of mind. He knows about the birth of Christ, and knows that it signaled an end of a way of thinking. Yet he had not yet understood the new way of thinking. He had not yet experienced the second death, required to become a Christian, the death entailed by Christ’s statement, “For whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it” (Matthew 16: 23).

Eliot was almost there. On June 29, 1927, after much soul-searching he finally and formally converted from Unitarianism to the Anglican Church. Thereafter, his poetry (for example, Ash Wednesday of 1930, Four Quartets of 1943) became intensely religious. Eliot who had described the emptiness of living without belief in the Wasteland now become reconciled to faith. His understanding, nevertheless, remained ecumenical. In the poems and plays that followed his conversion, elements of Eastern religions permeate the basic tenets of his Christian belief.

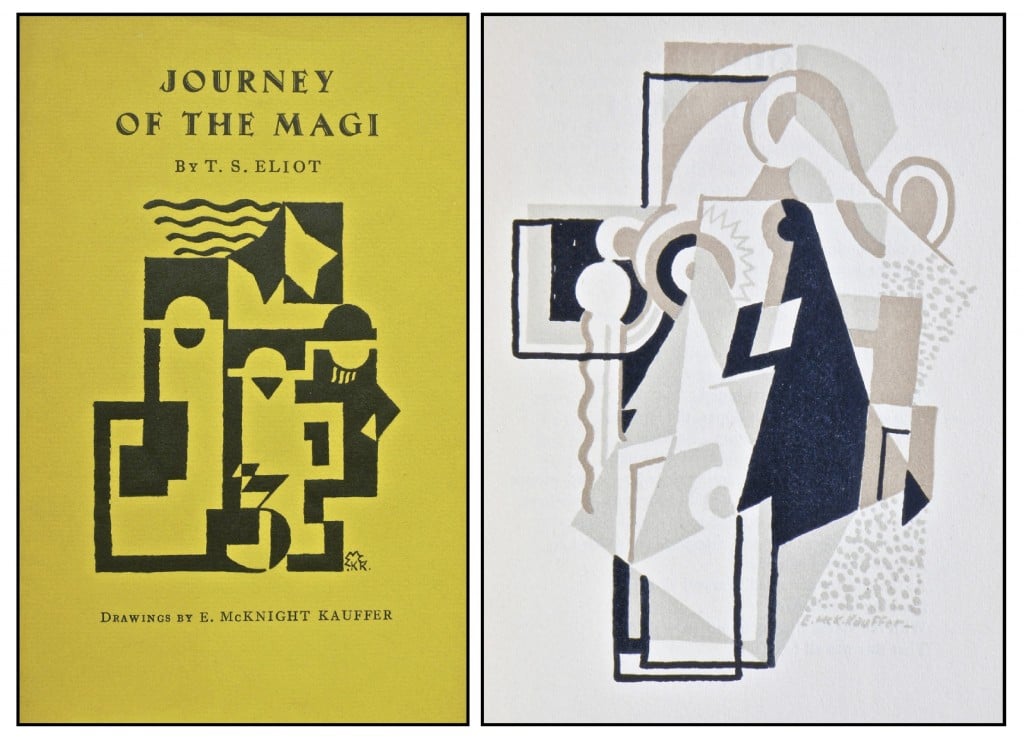

The change in thinking that is represented by Eliot’s conversion has analogies in other changes. Eliot’s poem was initially published as a pamphlet by Faber and Gwyer with illustrations by Edward McKnight Kauffer:

The cover is an exercise in two-color cubism that fits the enthusiastic expectations of the Magi. The internal illustration of the Nativity at the end of their journey shows the many subtle levels of meaning in the event. The change in art from realism to modernism was perhaps as great as the change in religion from before to after Bethlehem.

Ahl, D. C. (1996).Benozzo Gozzoli. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Andrewes, L. (1622, transcribed by Dorman, M., 2001) Sermon on the Nativity preached on Christmas Day 1622.

Dorman, M. Andrewes’ influence on Eliot

Eliot, T. S. (1927). The Journey of the Magi. London: Faber & Gwyer

Eliot, T. S. (1968). Collected poems: 1909-1962. London: Faber and Faber.

Haworth-Booth, M. (2005). E. McKnight Kauffer: A designer and his public. London: Victoria &Albert Museum.

Ozick, C. (1989). T.S. Eliot at 101, The New Yorker, November 20, 1989, p. 119-154.

Raine, C. (2006). T. S. Eliot. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Leave a Reply