Frames of Reference: The Art of William Kurelek

This post discusses the life and work of William Kurelek (1927-1977), one of the most distinctive and prolific Canadian painters of the latter half of the 20th Century. Kurelek was a figurative artist during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism, and a fervent Christian artist in the years of unbridled secularism. His work should be considered in the context of a life framed by memory, madness and religion (Kurelek, 1980; Morley, 1986). The post contains illustrations of many of his paintings, which can speak for themselves independently of my commentary.

Early Life

William Kurelek was born in Whitfield, Alberta, in 1927. His father Dmytro, who had immigrated to Canada from Bukovina in the Ukraine, was unable to make his first farm successful during the Depression, and moved the family to Stonewall, Manitoba in 1933. Kurelek remembered his childhood fondly, even though he did not get along well with his father. His 1968 painting Reminiscences of Youth shows a winter scene on the Prairies with children playing on a snow-covered haystack. The style owes something to Breughel’s paintings of Flemish life, but is distinct in the openness of its space and the flatness of the figures. It has the sentimentality of a Norman Rockwell illustration but is far more naïve. In the surrounding frame we see the teenage artist lying on his bed in a darkened room and remembering his childhood. The painting is thus a memory of a memory.

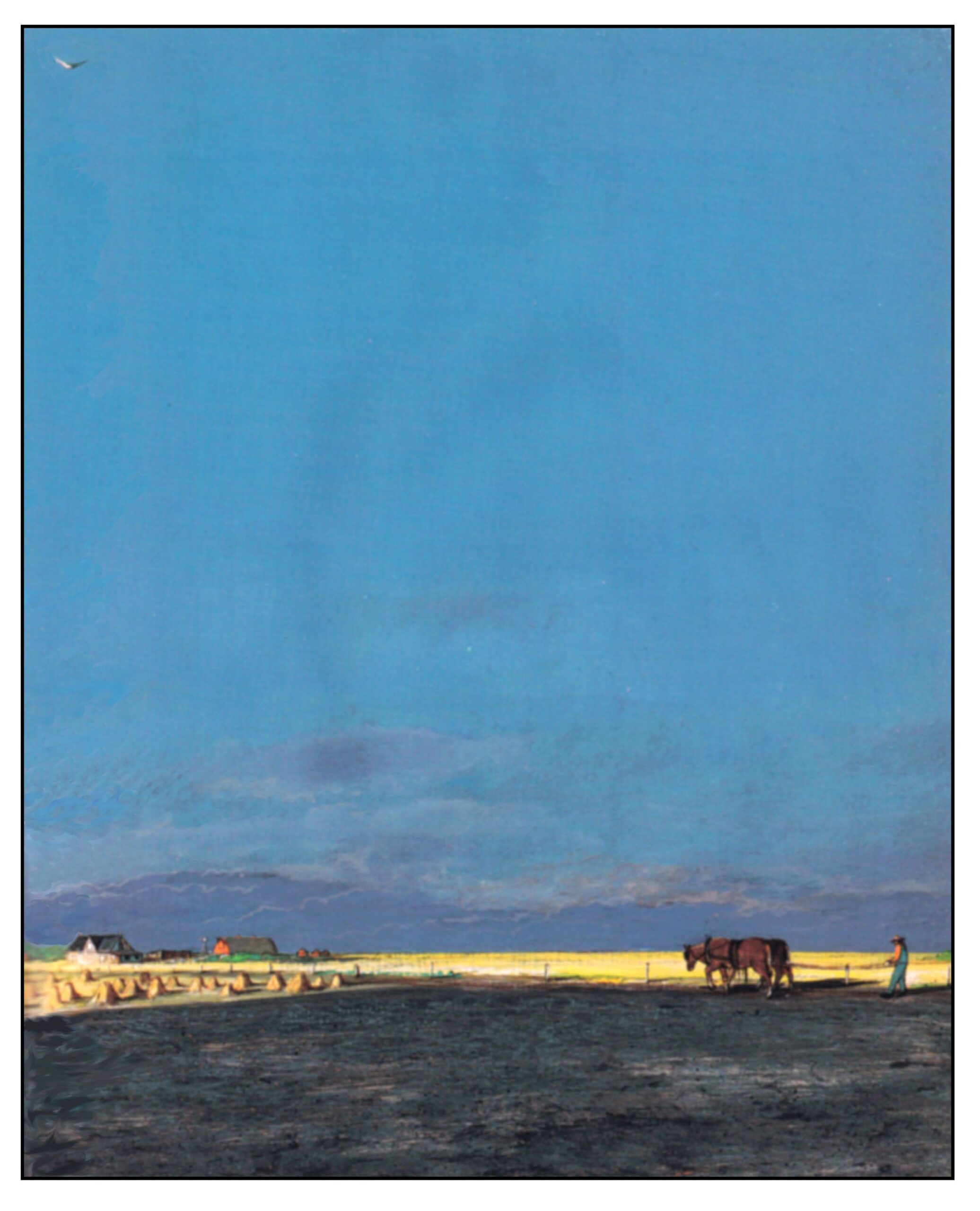

Kurelek’s memories of his childhood formed the basis of two books: A Prairie Boy’s Winter (1973) and A Prairie Boy’s Summer (1975). They also provided the illustrations for a new edition of W. O. Mitchell’s Who Has Seen the Wind (1976), from which the following image is taken. It contrasts the tininess of human endeavors with the immensity of a prairie sky as depicted by the flight of a bird:

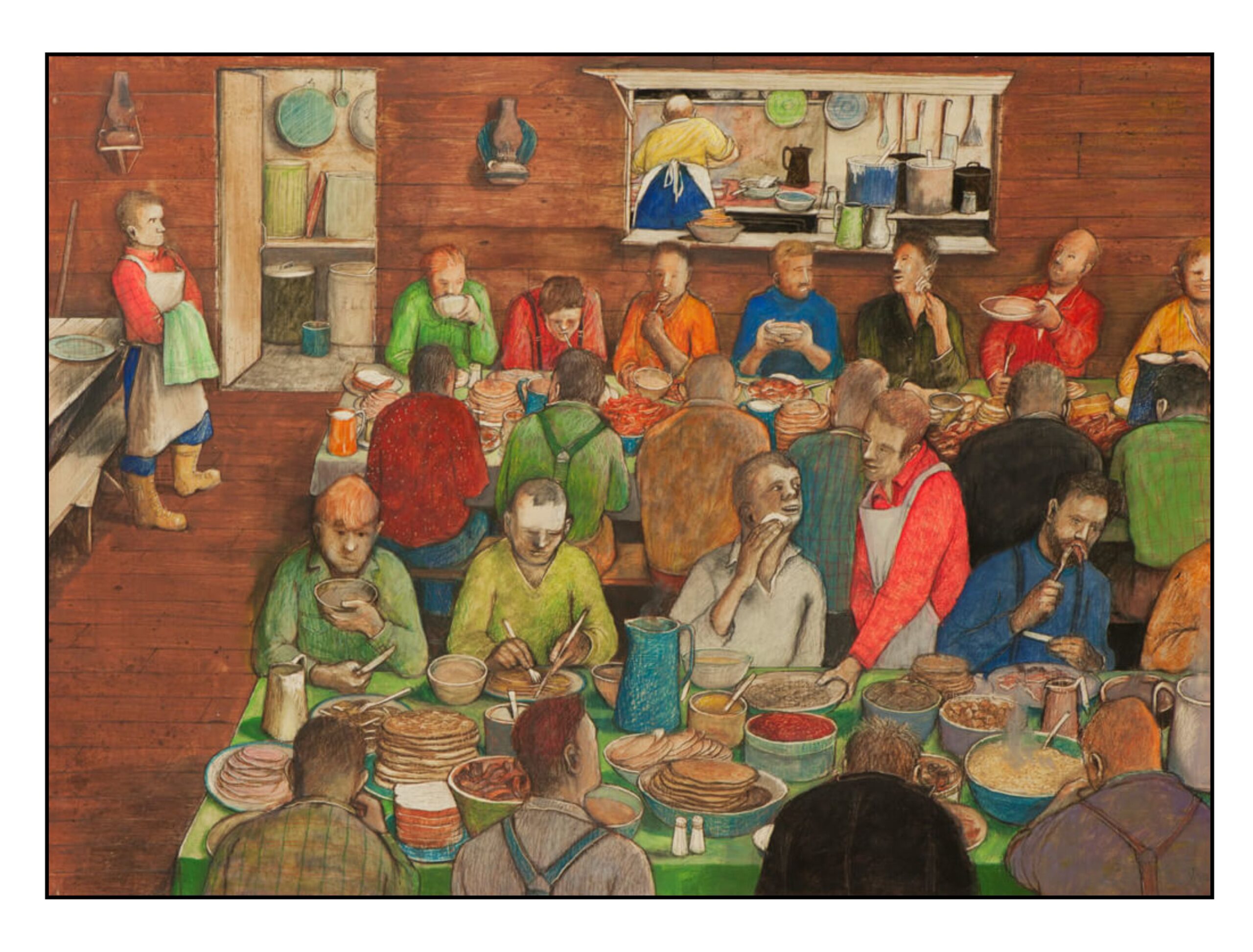

Kurelek did well at school and graduated in arts from the University of Manitoba in 1949. He then attended the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, his family having moved to Vinemount, in the Niagara Peninsula near Hamilton, in Southern Ontario. Though convinced of his own talent, Kurelek found himself unable to make any living from his art. He worked as a lumberjack in Northern Ontario to obtain money to travel to Europe. The following illustration of a Lumberjack’s Breakfast comes from his 1974 book entitled Lumberjack. It shows the tremendous energy and warm camaraderie of breakfast in the bush camps.

London

In London in 1952, Kurelek found a place to stay, visited museums and considered taking art classes. He travelled briefly to Paris, Brussels and Vienna to see the work of various masters. He was particularly impressed by the paintings of Bosch, Brueghel and Van Gogh. Back in London, he worked briefly as a laborer for the London Transport Commission. Alone and impoverished, he became severely depressed. After being unsuccessfully treated as an outpatient, he was admitted to the Maudsley Psychiatric Hospital. His occupational therapist there, Margaret Smith, encouraged his art, and introduced him to Roman Catholicism. With Margaret’s encouragement, he began to take religious instruction. His painting, The Maze (1953), was his attempt to understand his own tortured mind:

The artist’s skull is shown split down the middle with its various chambers open to the view of his psychiatrists. In the center the soul lies inert like an exhausted rat unable to find its way out of the maze of its mind. In the upper right is a scene of childhood bullying. Lower on the right a relentless conveyor built carries the person toward an inevitable death. At the lower center, doctors probe a human being inside a test-tube. A panel to left of this shows crows tormenting a lizard. The illustration below (not to scale) shows some of these sections. The painting is more intensively analyzed in Wikipedia and in the DVD entitled The Maze (2015).

Late in 1953, his psychiatrists transferred him the Netherne Psychiatric Hospital in Surrey, where Edward Adamson had established a program in art therapy. His room at the Netherne looked out over a cabbage patch. One night there Kurelek had a nightmare-vision of God calling for him from beyond the cabbage patch. He had been reading Francis Thompson’s 1890 poem The Hound of Heaven, which describes the soul’s flight from the grace of God. Though ever-rejected God keeps following after the soul to provide him, once he submits to grace, with love and salvation. The title of Kurelek’s 1970 painting depicting this nightmare comes from the poem – All Things Betray Thee Who Betrayest Me.

The painting shows the Hound of Heaven in tiny outline just beyond the cabbages on the far right. On the window sill a small glass of water depicts the grace of God. Thompson’s poem ends with the soul finally reconciled to God who states:

How little worthy of any love thou art!

Whom wilt thou find to love ignoble thee,

Save Me, save only Me?

All which I took from thee I did but take,

Not for thy harms,

But just that thou might’st seek it in My arms.

All which thy child’s mistake

Fancies as lost, I have stored for thee at home:

Rise, clasp My hand, and come!”

Halts by me that footfall:

Is my gloom, after all,

Shade of His hand, outstretched caressingly?

Ah, fondest, blindest, weakest,

I am He Whom thou seekest!

Thou dravest love from thee, who dravest Me.

At the Netherne, Kurelek continued his paintings in the workshop. However, he still found no easy way out of his agony. He attempted suicide and was given a course of Electro Convulsive Therapy.

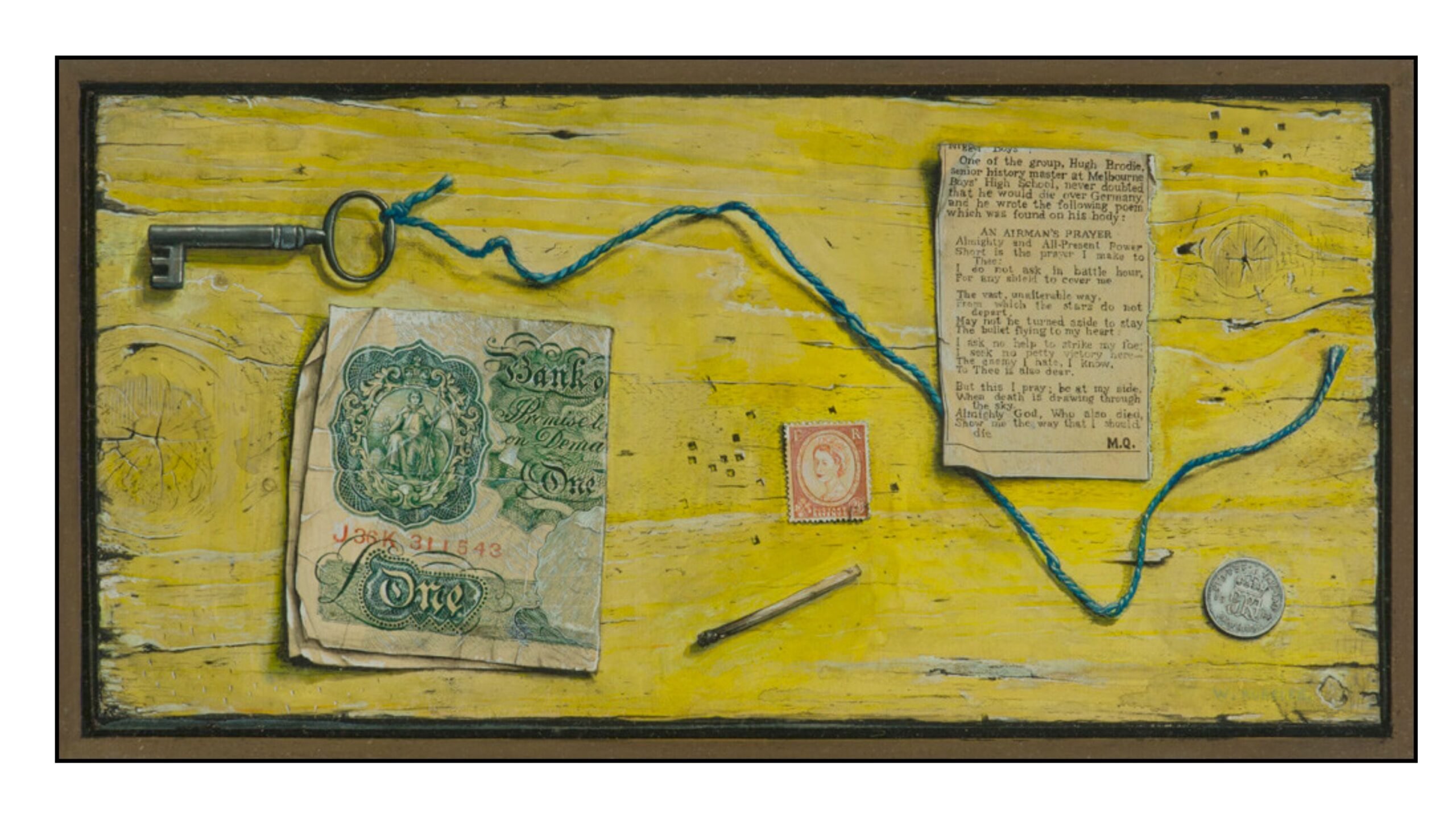

During the ensuing year, he slowly improved, and in 1955 he was discharged from the hospital. He was able to make a living by selling small evocative trompe-l’oeil paintings such as The Airman’s Prayer, which shows the key to the life of an airman who died in service of his country (represented by the stamp). In the end, his life was “not worth a sixpence.” On the right is the prayer of Australian airman Hugh Brodie written prior to his death and published afterwards in the newspapers. It ends

But this I pray – be at my side

When death is drawing through the sky,

Almighty God, Who also died,

Teach me the way that I should die.

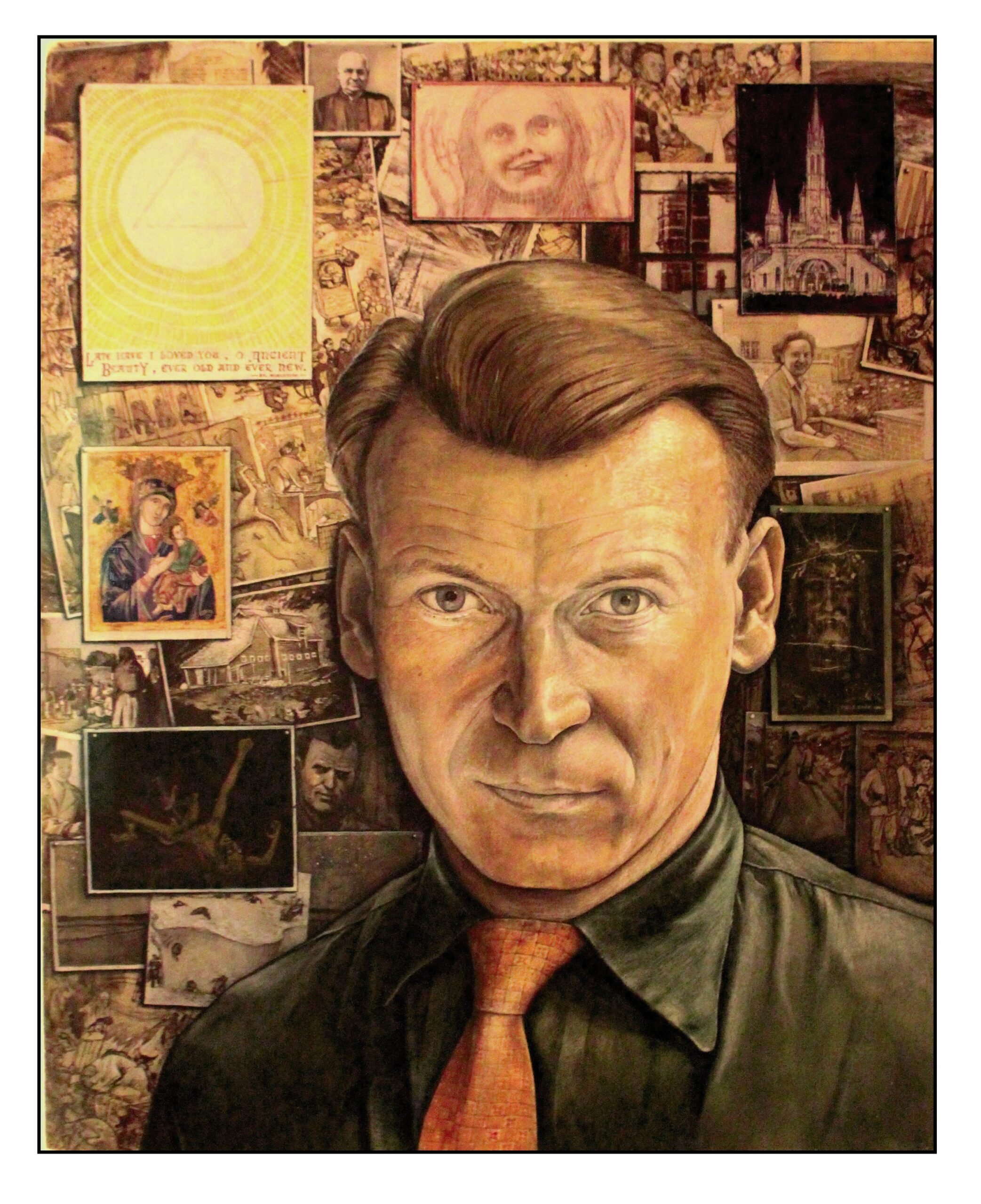

After his discharge, Kurelek travelled home to Canada, but was unable to find stable work. He returned to England and obtained a position in the framing shop of F. A. Pollak, where he learned to be an expert framing craftsman. He completed his religious instruction with Father Thomas Lynch, formally converted to Roman Catholicism in 1957, and made a pilgrimage to Lourdes. The Self Portrait of 1957 shows an artist fully in control of his own destiny:

The background represents in trompe-l’oeil style various pictures, postcards and photographs pinned to the wall. In the upper left we can see an abstract representation of the Trinity with a quotation from St Augustine, “Late have I loved you, O Ancient Beauty, ever old and ever new.” Also at the upper edge are a photograph of Father Thomas Lynch, a drawing of Sainte Bernadette Soubirous, who experienced the vision of the Virgin at Lourdes, and a picture of the Rosary Basilica in Lourdes. Below the Basilica are a photograph of Margaret Smith, Kurelek’s occupational therapist at Maudsley, and a representation of the Shroud of Turin. On the left side, a representation of the 15th-Century icon Our Lady of Perpetual Help is superimposed on a reproduction (or preliminary drawing?) of Kurelek’s 1955 painting Behold Man without God. At the lower left are an illustration of one of the damned in Hell (from I am not sure which Northern Renaissance painting), and a photograph of Kurelek’s father Dmytro.

Toronto

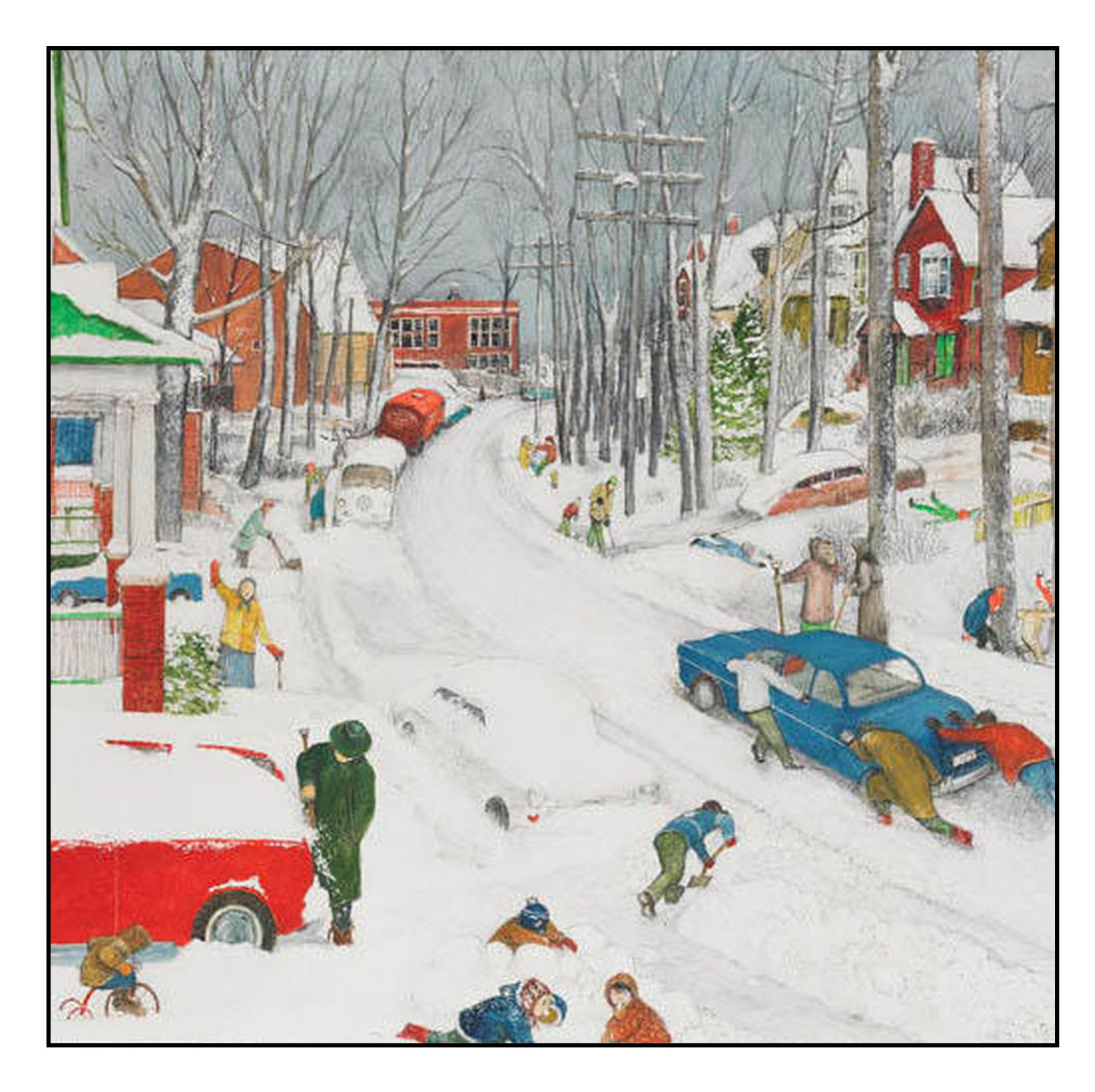

When Kurelek returned to Toronto in 1959, Av Isaacs, owner of a small gallery, was impressed by his paintings and arranged a showing in 1960. Perhaps more importantly, he was able to employ Kurelek as a framer in his gallery. This work provided the artist with a secure income while he painted. Kurelek married in 1962 and raised three children. As well as publishing books based on his past, Kurelek also painted scenes from his Toronto Life. The following shows a winter scene near his home: Balsam Avenue after Heavy Snowfall (1973).

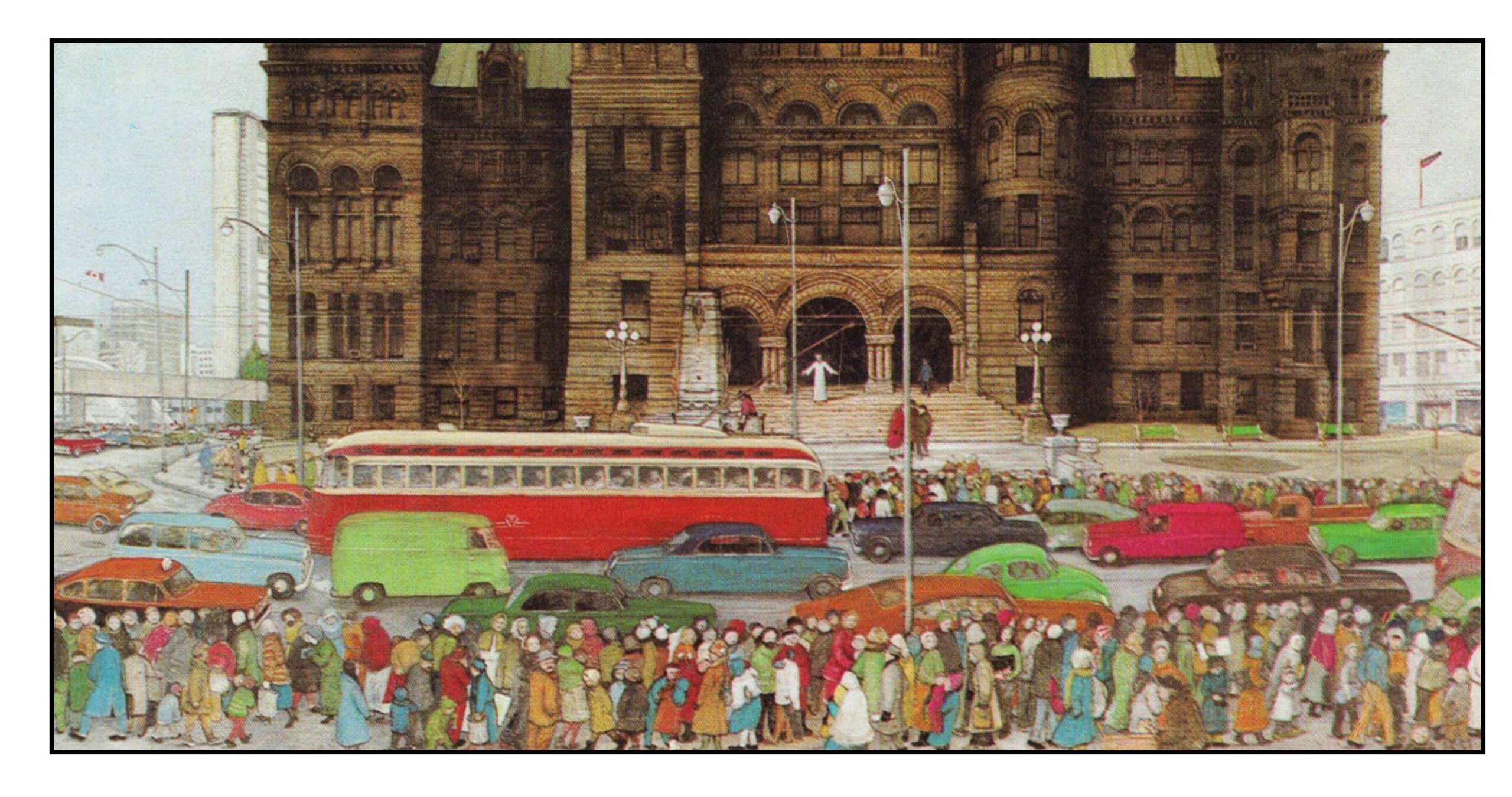

Kurelek had become a fervent Catholic, and some degree of sermonizing soon began to intrude into his paintings. This can be intriguing as in Toronto, Toronto (1973) which shows a small figure of Christ lamenting on the steps of the Old City Hall as Christmas shoppers pass by and pay him no attention. It was the same when he had bewailed the state of Jerusalem many centuries before:

O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, thou that killest the prophets, and stonest them which are sent unto thee, how often would I have gathered thy children together, even as a hen gathereth her chickens under her wings, and ye would not! (Matthew 23:37)

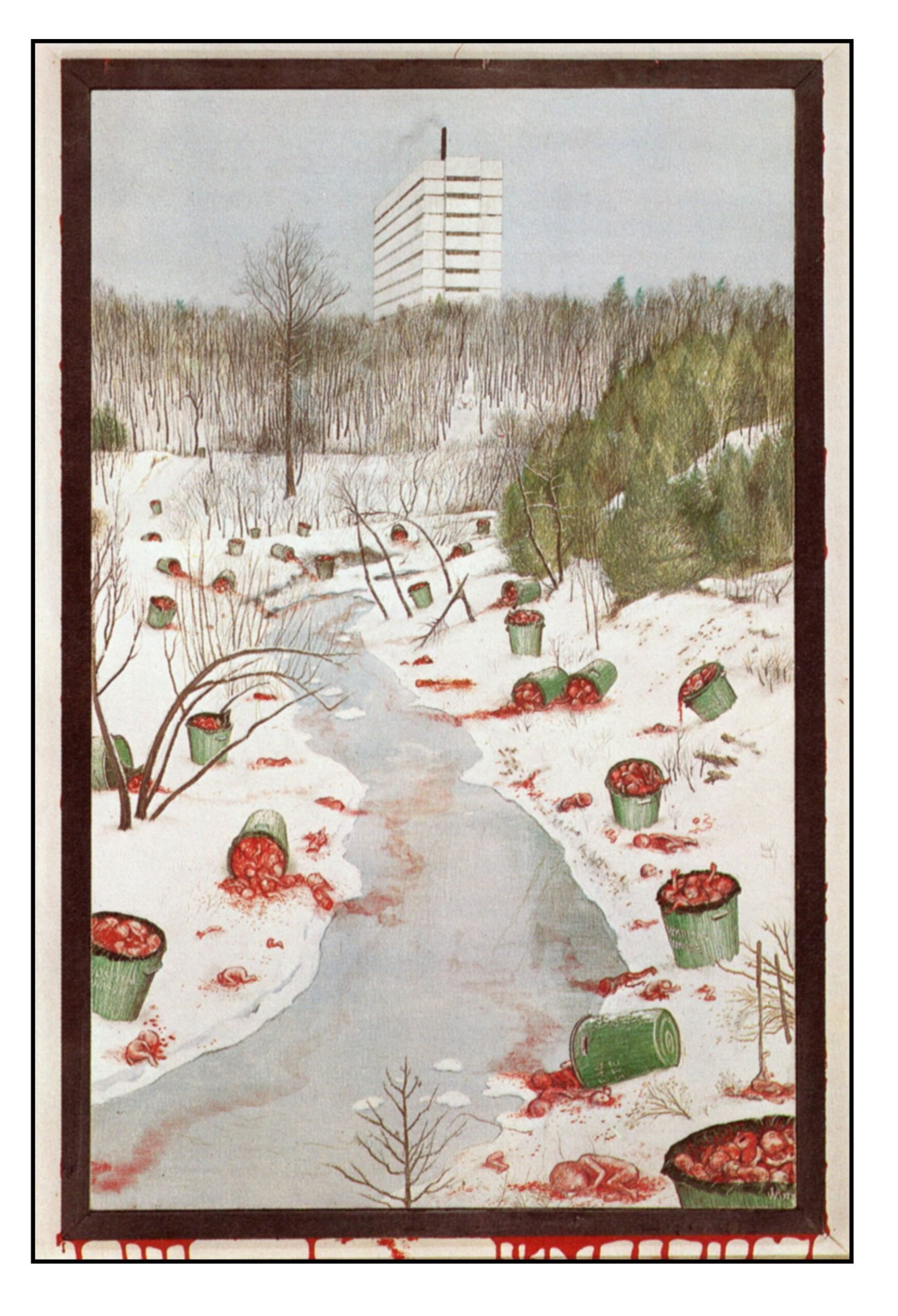

Sometimes, however, Kurelek’s imagery becomes offensive, as in Our My Lai, the Massacre at Highland Creek (1973), which shows aborted fetuses from the Scarborough Centennial Hospital in Toronto. My Lai was the site of a 1968 massacre in Vietnam. Therapeutic abortions (to preserve the life or health of the mother) were legalized in Canada in 1969, though it was not until 1988 that abortions became more readily available. There is nothing more insufferable than a new convert’s absolute certainty about what is right and what is wrong.

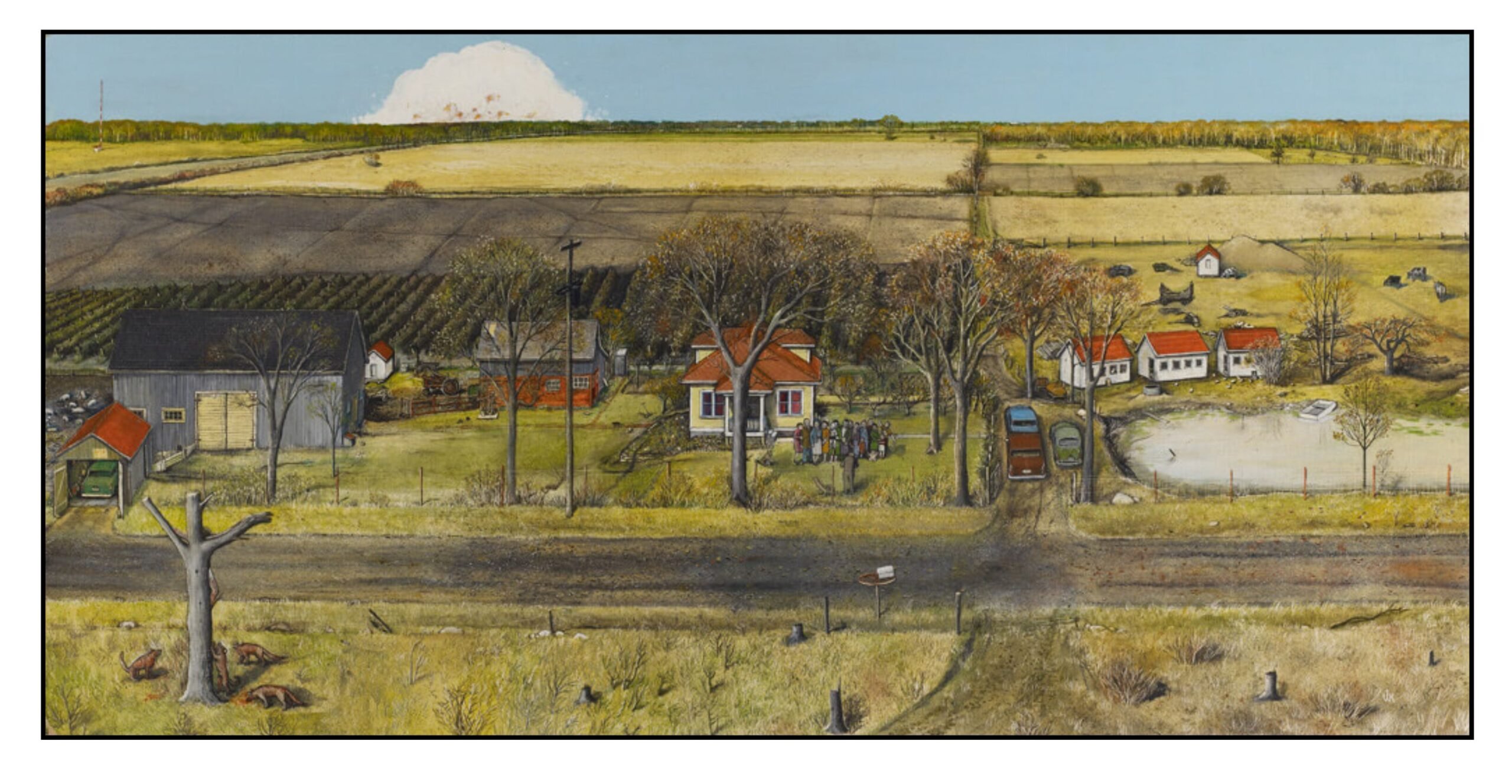

Kurelek also began to fuse Christian apocalyptic thinking with ongoing fears of a nuclear war. The Cuban Missile Crisis of1962 had brought the world very close to Annihilation, and Kurelek had made a basement studio in Balsam Avenue like a bomb-shelter. In the Autumn of Life (1964) shows the Kurelek family at the Vinemount farm.

The extended family gathers on the lawn for a photograph. However, this is not just a record of the family’s success. As Andrew Kear (2017) points out

Closer study of the painting reveals several disquieting elements that undermine the painting’s function as a sincere celebration of social mobility. A Christ figure appears in the bottom-left foreground, crucified on a dead tree and surrounded by ravenous dogs that clamour over the spilled blood. The dogs, Kurelek later wrote, “are supernatural” ones, referring to the enemies of Christ mentioned in the Book of Psalms. More foreboding still is the giant mushroom cloud that Kurelek uses as the iconic symbol of nuclear war and a reminder that technological advancement does not necessarily make for peace and harmony.

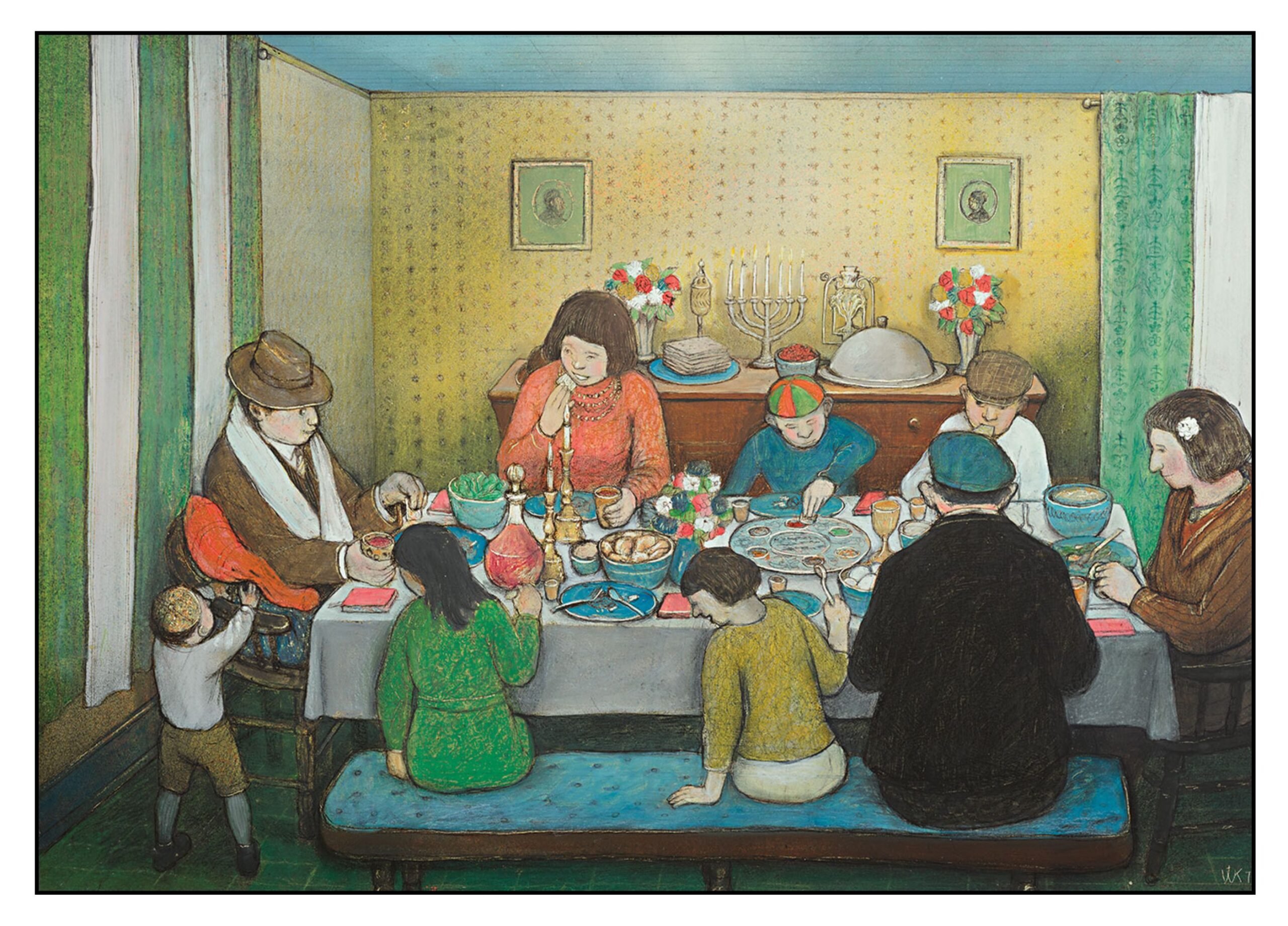

Kurelek illustrated several books about the immigrant experience in Canada: Jewish Life in Canada (1976), They Sought a New World (1985), The Polish Canadians (1981). The following shows Jewish Doctor’s Family Celebrating Passover in Halifax (1976):

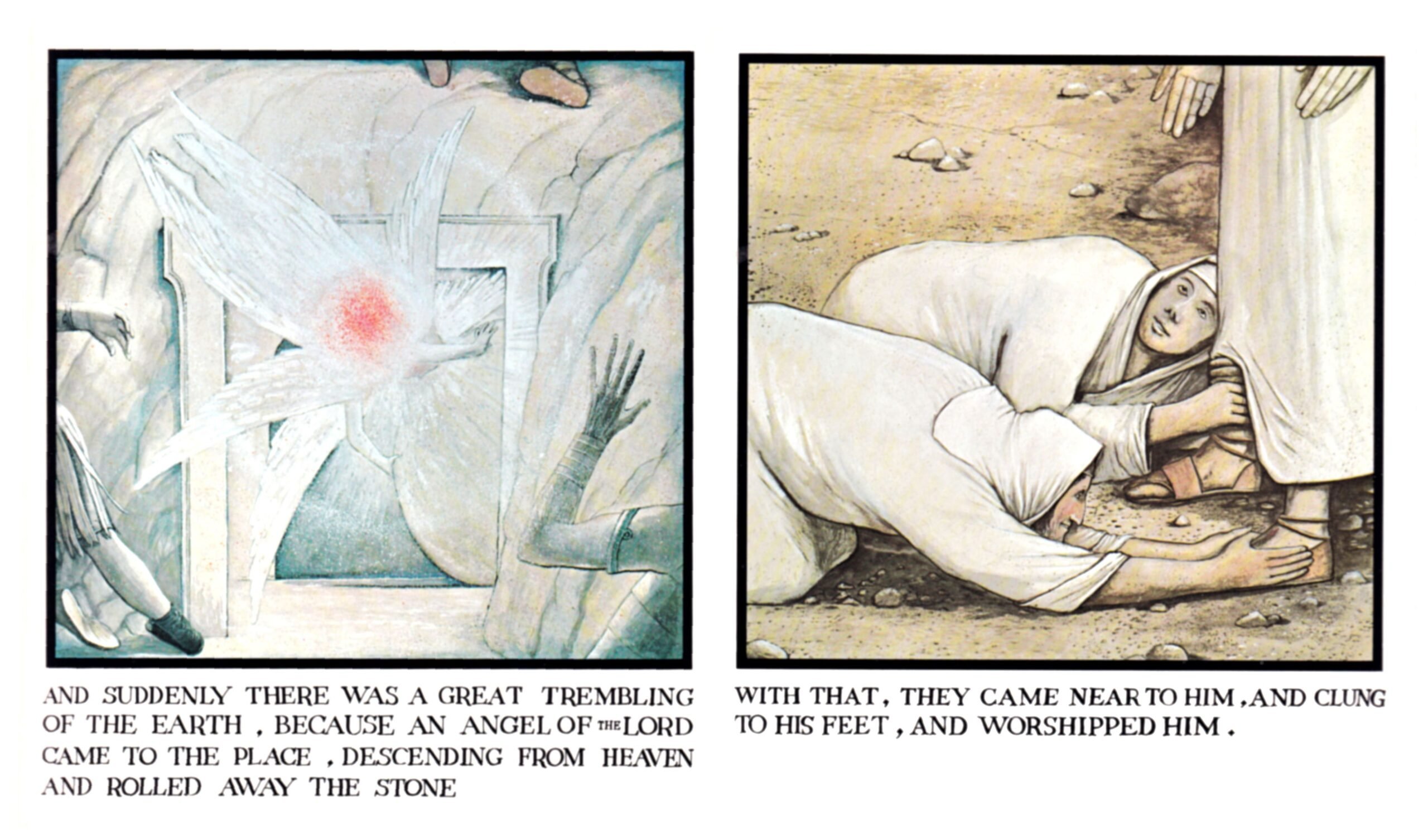

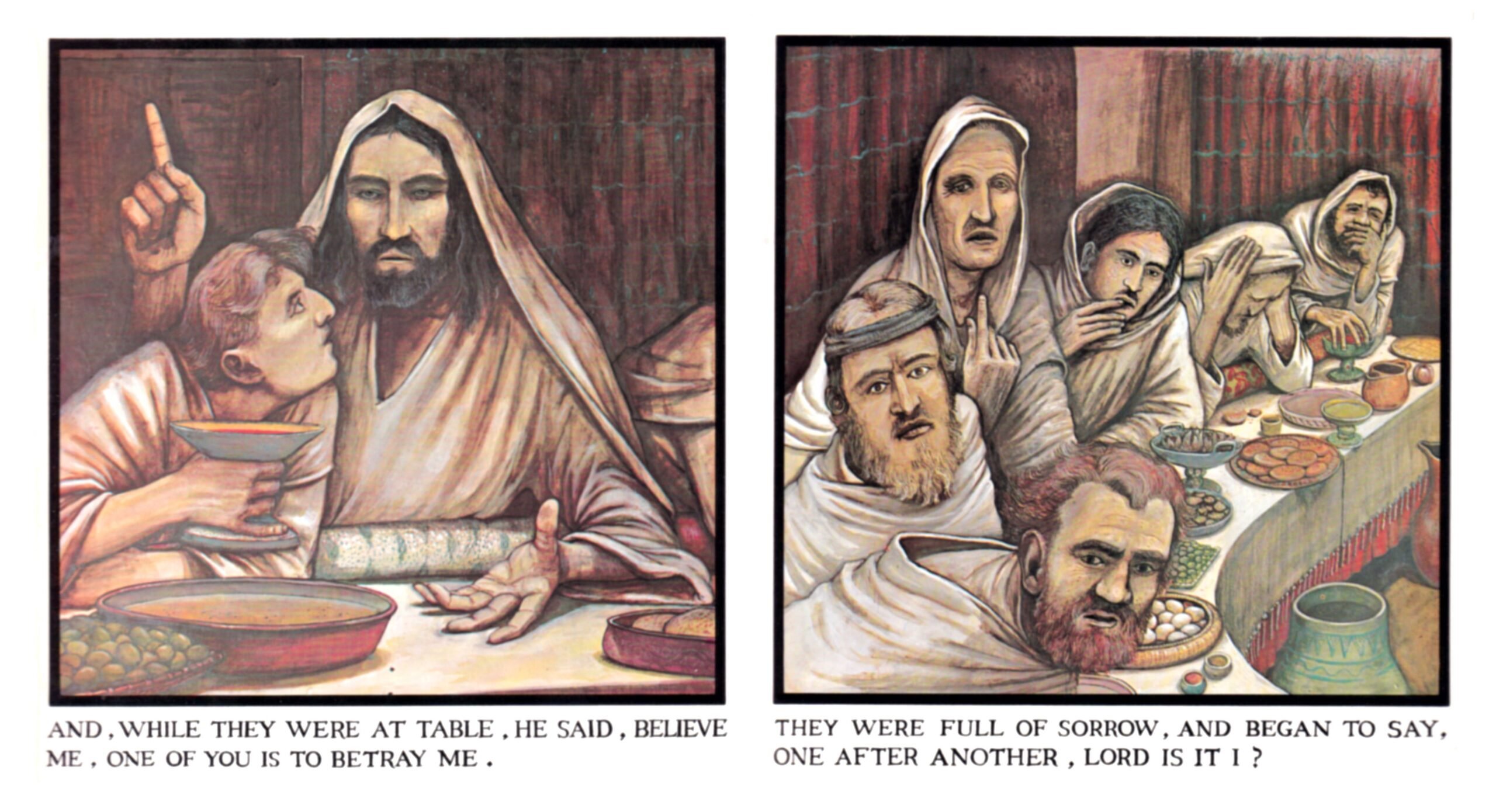

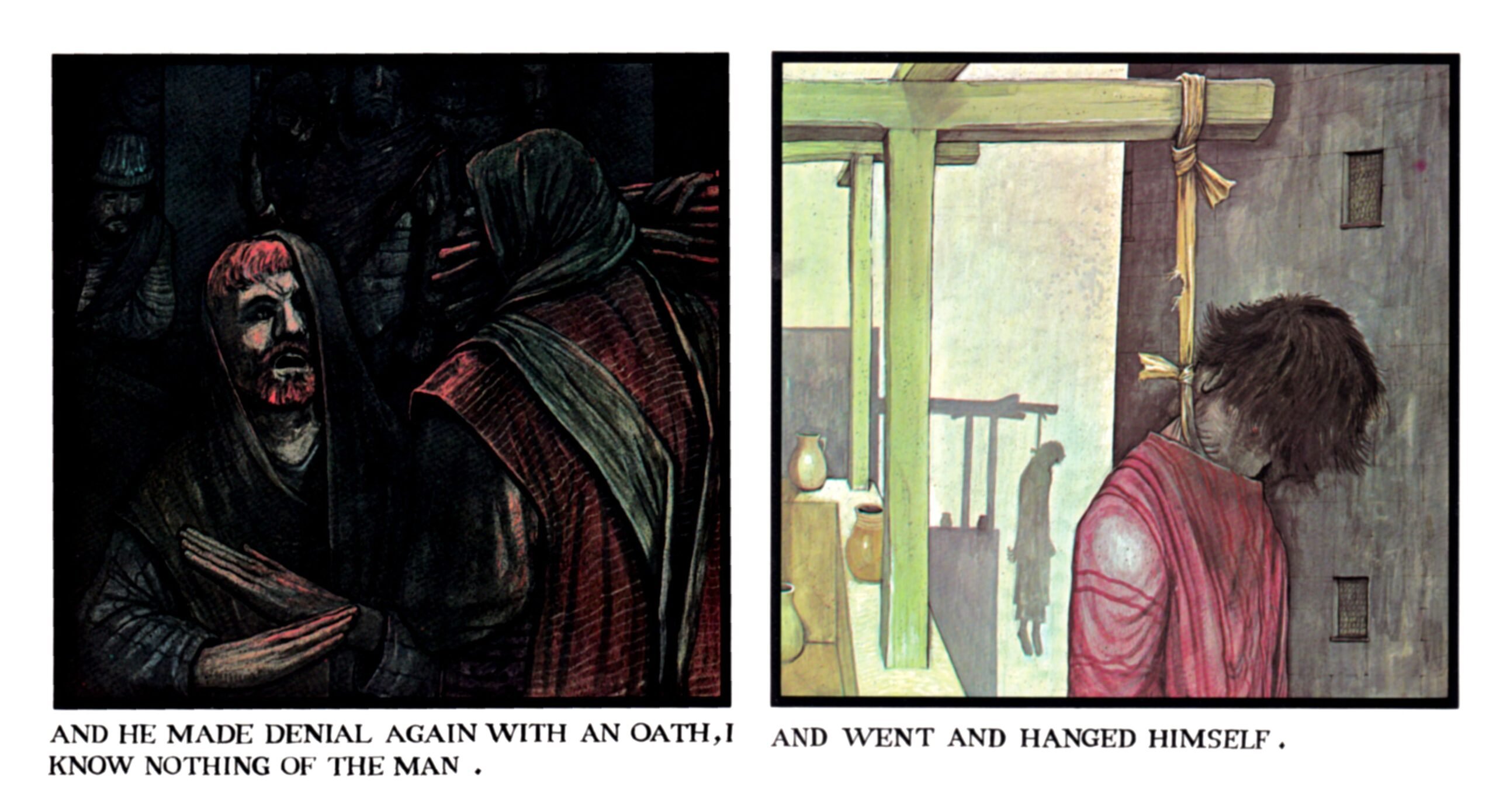

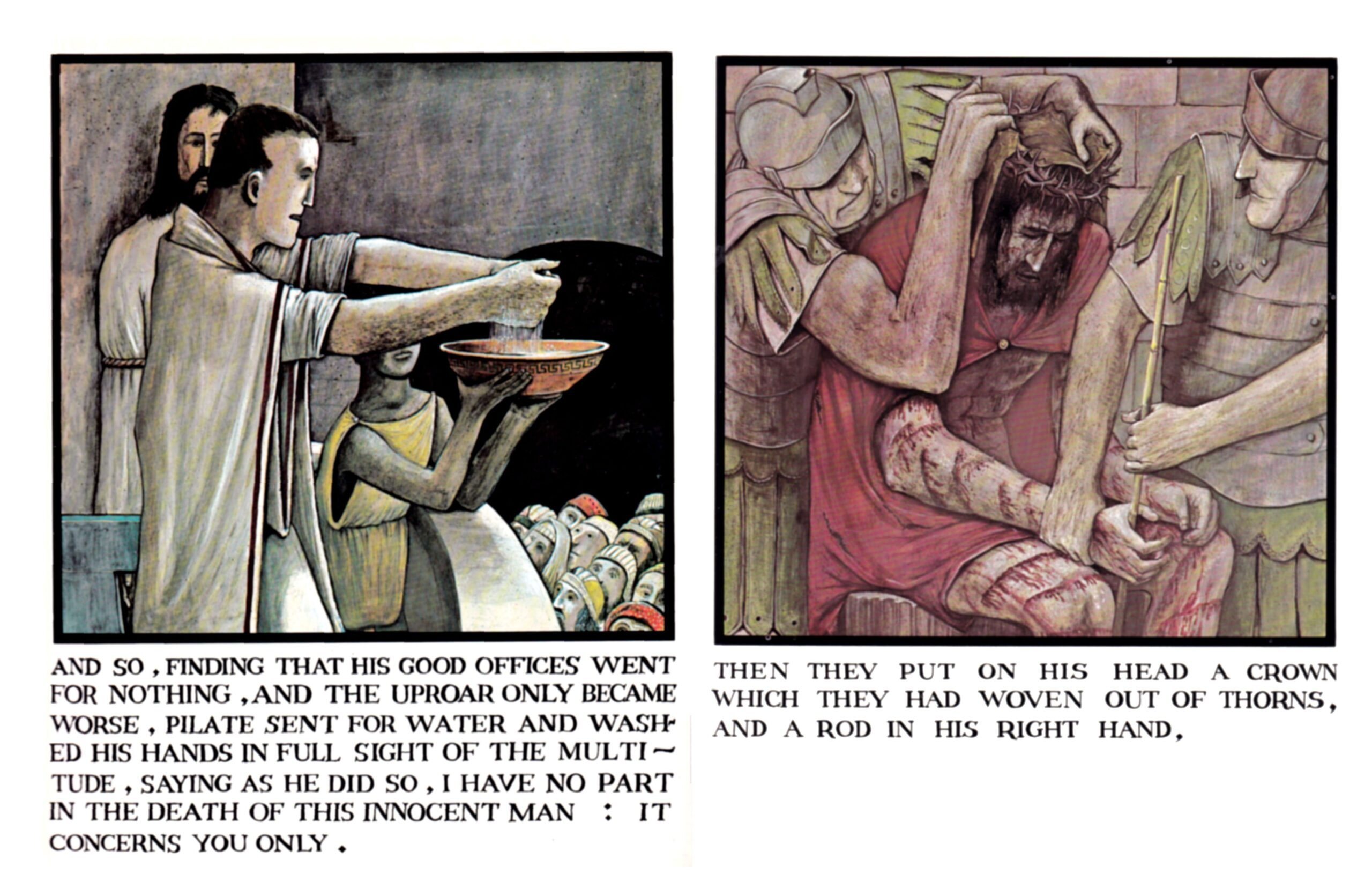

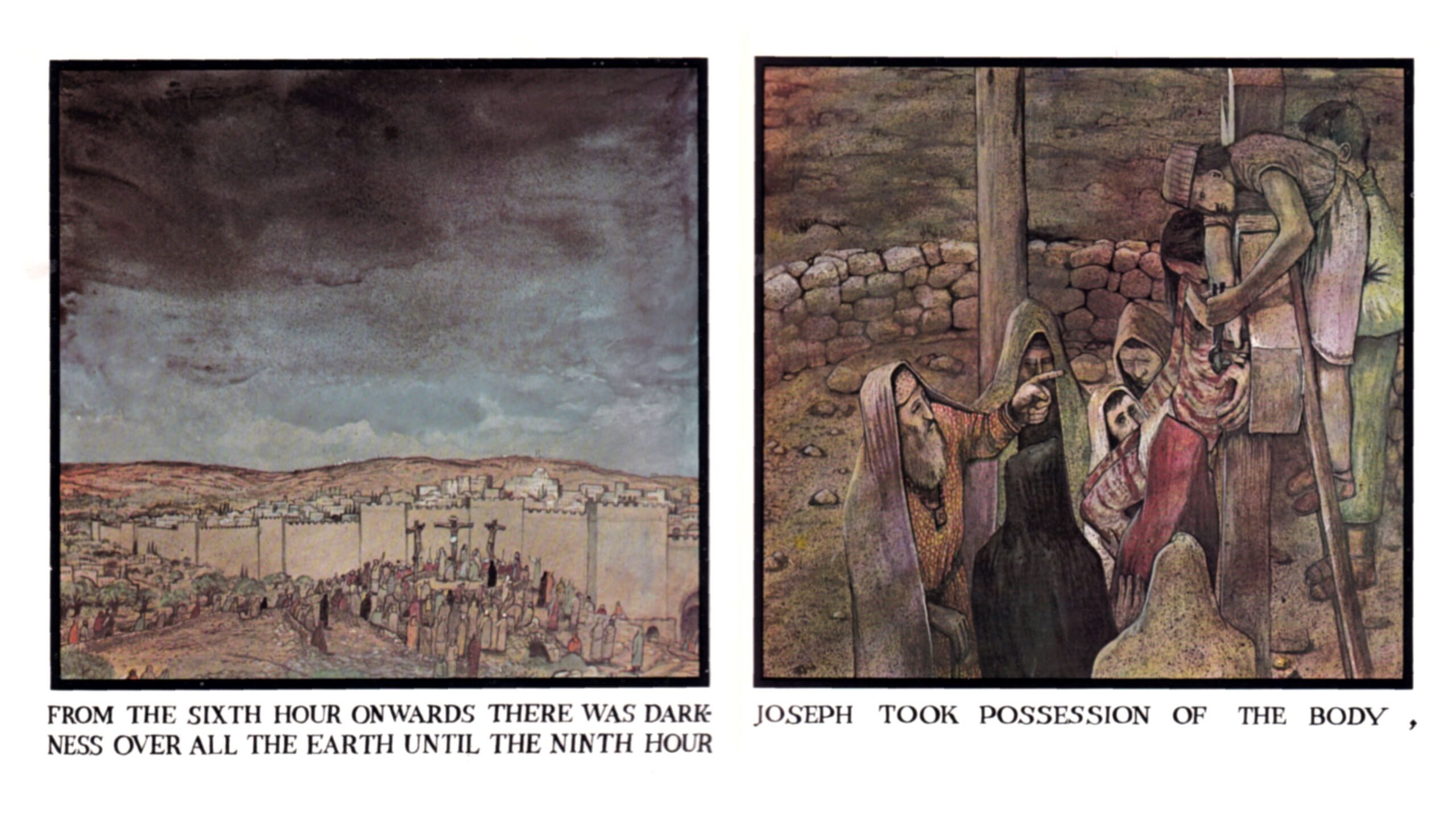

Kurelek spent much of the sixties producing a series of 160 paintings based on The Passion of Christ according to St. Matthew (1975). In London after his discharge from the psychiatric hospital, Father Lynch had given him a second-hand copy of Tissot’s Life of Christ (1896, Dolkart et al, 2009). In 1885, James Tissot (1836-1902), a successful painter of London society and fashion, experienced a religious conversion. He subsequently traveled to the Holy Land and produced a large set of paintings to illustrate the Gospels. Kurelek’s paintings derived conceptually from both the water-colors of Tissot and the passion paintings of Bosch and Brueghel, but were created in his own idiosyncratic neo-medieval way. They range in form from close-up portraits to bird’s eye views, from populous crowd scenes to lonely individual portraits, from sunny landscapes to dark interiors. In a way they serve as a storyboard for an imaginary film – each painting showing the view of a particular camera set-up, some of them very original. The following illustrations show some selected paintings (in sequence but only occasionally contiguous):

The figure of Christ is perhaps overly simplified: he has little expression beyond severity and agony. Some of the crowd scenes portray Jews that are almost antisemitic caricatures. Part of this may be caused by the actual text of Matthew, the gospel most prejudiced against the Jews. Despite these shortcomings, many of the paintings have an emotional depth that transcends their simplicity.

The figure of Christ is perhaps overly simplified: he has little expression beyond severity and agony. Some of the crowd scenes portray Jews that are almost antisemitic caricatures. Part of this may be caused by the actual text of Matthew, the gospel most prejudiced against the Jews. Despite these shortcomings, many of the paintings have an emotional depth that transcends their simplicity.

Critical Assessment

Kurelek’s work is difficult to evaluate. When he wanted – as in his trompe-l’oeil paintings – he could be acutely aware of perspective and shadow. However, his figures are generally outlined with minimal shading and solid coloring. In most of his work, therefore the people feel flat and the space appears two-dimensional. In some ways these pictures harken back to those of the late medieval period or early Renaissance, but in other ways they become almost caricatures like newspaper cartoons. Some of his paintings have an endearing charm; others are ponderously didactic. Of the contradictions inherent in his work and character, Ilse Friesen (1997, p 177) remarks

Kurelek’s art is both realistic and abstract, both amateurish and expert, both naïve and sophisticated, both mundane and mystical … his personality is both humble and arrogant, educated and provincial, compassionate and judgmental, even saintly and devilish.

The series of Passion paintings probably represents Kurelek’s greatest achievement. The simplicity of his figures in this series sometimes allows them to carry intense emotion. Like the work of Expressionists like Munch and Nolde, they can have a tremendous power.

References

Baker, M. (2015). Framing Kurelek. Canadian Ethnic Studies, Suppl. Special Issue: The Ukrainian Canadians. 47.4/511-548.

Bruce, T., Hughes, M. J., & Kear, A. (2011). William Kurelek: The messenger. Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Dedora, B. (1989). With WK in the workshop: a memoir of William Kurelek. Aya Press/Mercury Press.

Dolkart, J., Sitar, A., & Morgan, D. (2009). James Tissot: the Life of Christ: the complete set of 350 watercolors. Brooklyn Museum.

Friesen, I. (1997). Earth, hell and heaven in the art of William Kurelek. Mosaic Press.

Hughes, M. J. (2011). The William Kurelek Theatre presents William Kurelek, An Epic Tragedy. In Bruce et al. (pp 39-55).

Kear, A. (2017). Willam Kurelek: Life and Work. Art Canada Institute

Kurelek, W., (1973). O Toronto. New Press (Toronto).

Kurelek, W., (1973). A prairie boy’s winter. Tundra Books.

Kurelek, W., (1975). A prairie boy’s summer. Tundra Books.

Kurelek, W. (1974). Lumberjack. Montreal: Tundra Books.

Kurelek, W. (1975). The Passion of Christ according to St. Matthew. Niagara Falls Art Gallery and Museum.

Kurelek, W. (1976). The last of the Arctic. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson.

Kurelek, W. (1978). Kurelek’s Canada. Toronto: Pagurian Press.

Kurelek, W. (1980). Someone with me: The autobiography of William Kurelek. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart.

Kurelek, W. (1981). The Polish Canadians. Tundra Books

Kurelek, W., & Arnold, A. (1976). Jewish life in Canada. Edmonton: Hurtig.

Kurelek, W., & Cook, R. (1999). Kurelek country: The art of William Kurelek. Toronto: Key Porter Books.

Kurelek, W., & Engelhart, M. (1985). They Sought a New World. Tundra Books.

Mitchell, W. O. (illustrated by Kurelek, W., 1976). Who has seen the wind. Macmillan of Canada.

Morley, P. (1986). Kurelek, a biography. Macmillan of Canada.

Pettigrew, W. (1967). Kurelek. National Film Board

Rak, J. (2004). Pain and painting: William Kurelek and autobiography as mourning Mosaic: A journal for the interdisciplinary study of literature. 37(2), 21-40.

Thompson, F. (1890). The Hound of Heaven Merry England, 15 (87), 163-168.

Tissot, J. (1896). La vie de notre Seigneur Jesus Christ: trois cent soixante-cinq compositions, d’après les Quatre Évangiles avec des notes et des dessins explicatifs. Alfred Mame et fils.

Young, R. M. & Grubin, D. (2015). William Kurelek’s The Maze. DVD

For some reason, I found this post especially interesting. Never heard of Kurelec (Have I walked past hist paintings while in the National Gallery in Ottawa?) Thanks for enlightening me.

Glad you liked it. The National Gallery has only a few of his paintings and I don’t remember any being on display. The Art Gallery of Toronto has a large collection with a whole room devoted to his work. I believe all the Passion paintings are in the Niagara Falls Art Gallery, which is hardly ever visited.