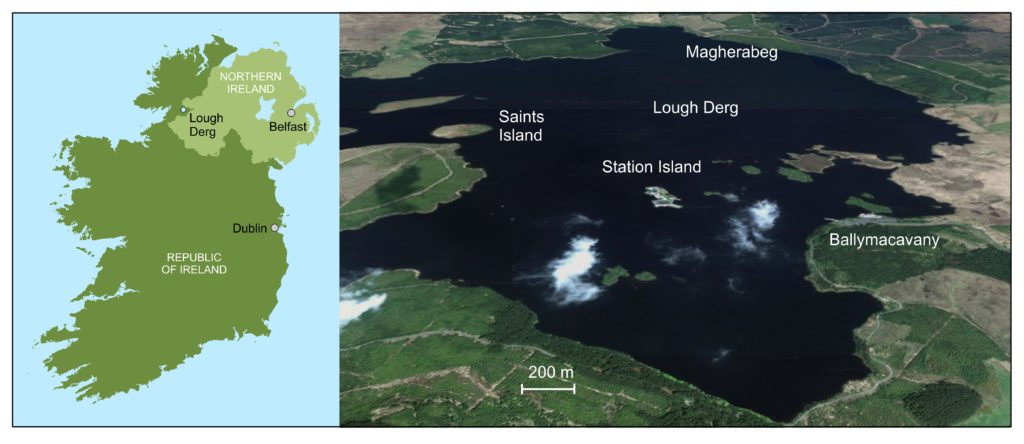

Station Island is an island in Lough Derg in County Donegal in the northwest part of the Republic of Ireland, very near the border with Northern Ireland. Lough Derg is a small shallow lake set amid low hills. Drainage from the surrounding bogs often gives its waters a russet hue, accounting for its name, “Red Lake” in Irish. Legend attributes the color to the blood of a monster serpent killed by St Patrick. Station Island has long been a place of Catholic Pilgrimage. This post presents some history of the pilgrims and of those who have written about them. Particular attention is paid to Seamus Heaney’s sequence of poems entitled Station Island (1984). The posting is long – like the pilgrimage.

Lough Derg

The following illustration presents an annotated view of Lough Derg from Google Earth. The view is toward the north and the scale is approximate. The ferry to Station Island leaves from Ballymacavany.

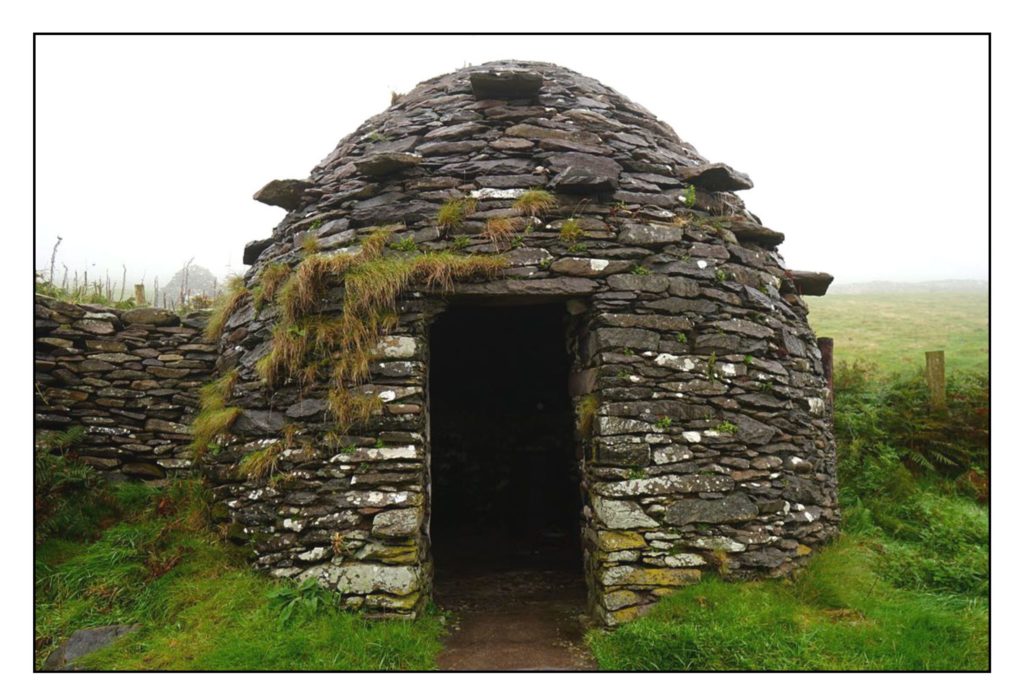

A monastic community has existed on Station Island since the 5th Century CE. The initial inhabitants were likely anchorites (from the Greek anachoreo, withdraw), believers who underwent a rite of consecration similar to the funeral rite. They then considered themselves dead to the world and never moved from their one place of worship. Station Island has six low circular stone structures that probably are the remains of the anchorites’ clochans (“beehive cells”). Such ancient structures are common in western Ireland. The following illustration shows a clochan from the Dingle Peninsula. Those on the Island of Skellig Michael have become famous after being used in the movie Star Wars: The Last Jedi (2017).

St Patrick, the Romano-British missionary, may have visited Station Island during his time in Ireland during the 5th Century CE. St Dabheog, a Welsh disciple of St Patrick, is generally recognized as the first abbot of Station Island. As we shall see, in the early Middle Ages the island was considered one of the locations of Purgatory. The island soon became a place of pilgrimage, where believers came to repent their sins and renew their faith. The remains of the clochans became “penitential beds” where the pilgrims prayed.

A Short History of Purgatory

Early Christian teachings proposed two possible afterlives. Those who believed in Christ and repented their sins went to Heaven; those who did not went to Hell. The scriptures provide extensive support for both Heaven and Hell. However, there was some uncertainty about when these afterlives began. Was it immediately after death, or did the deceased have to wait until the Second Coming and the Resurrection of the Dead? If the latter, what happened in the meantime? Or is the idea of time after death without meaning?

The New Testament contains occasional references to being tested by fire after death:

That the trial of your faith, being much more precious than of gold that perisheth, though it be tried with fire, might be found unto praise and honour and glory at the appearing of Jesus Christ. (1 Peter 1:7).

In addition, another scriptural verse suggested that prayers could facilitate removal of sin from those who have died:

It is therefore a holy and wholesome thought to pray for the dead, that they may be loosed from sins. (2 Maccabees 12:46).

During the early Middle Ages, Christian theologians such as Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas began to consider a third afterlife in addition to Heaven and Hell (Le Goff, 1984; Greenblatt, 2001). Perhaps there was a place or state where believers were cleansed or purged of their sins. Christ died to wash away the sins of the believers, but perhaps there was still some taint of sin that needed to be removed before entry into Heaven. After much discussion the Catholic Church accepted this idea at the Second Council of Lyon in 1274 (Denzinger et al., 2012, p. 283):

Those who after baptism lapse into sin must not be rebaptized but must obtain pardon for their sins through true penance. If, being truly repentant, they die in charity before having satisfied by worthy fruits of penance for their sins of commission and omission, their souls are cleansed after death by purgatorial and purifying penalties … and to alleviate such penalties the acts of intercession of the living faithful benefit them, namely, the sacrifices of the Mass, prayers, alms, and other works of piety that the faithful are wont to do for the other faithful according to the Church’s institutions.

The concept of purgatory was quickly taken up as an essential part of Christian culture. Dante’s Divine Comedy completed in 1320 vividly imagined the tripartite afterlife: Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. Many aspects of Purgatory remained unclear. Could mortal sins be removed or just venial sins? What was the nature of the purification process? Dante had the souls pass through fire only at the end of their ascent of Mount Purgatory. Others proposed that the fires of Purgatory were similar to those of Hell. However, the fires of Purgatory served to purify rather than to punish, and were limited in time rather than eternal. A terrifying description of Purgatory is given by the ghost of Hamlet’s father (Greenblatt, 2001):

I am thy father’s spirit,

Doom’d for a certain term to walk the night,

And for the day confined to fast in fires,

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison-house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

Make thy two eyes, like stars, start from their spheres,

Thy knotted and combined locks to part

And each particular hair to stand on end,

Like quills upon the fretful porcupine:

But this eternal blazon must not be

To ears of flesh and blood. (Hamlet I: 5)

This is Brian Blessed as the Ghost in Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 movie of Hamlet:

The idea of Purgatory and the belief that prayers and alms could help reduce the suffering of souls in Purgatory soon led to corruption. In the later Middle Ages the church began to raise money from the faithful by selling “indulgences” as a way to reduce the amount of punishment one has to undergo in purgatory. These could be purchased for the benefit of either the dead or the living. The abuse of this process was one of the main factors leading to the Protestant Revolution. None of the Protestant churches recognize Purgatory. For example, the Articles of Religion of the Church of England state that the doctrine of Purgatory is “a fond thing vainly invented, and grounded upon no warranty of Scripture, but rather repugnant to the Word of God.”

St Patrick’s Purgatory

Legend states that while St Patrick was on Station Island he had a vision of the afterlife in a cave on the island. In 1184 a monk who signed himself “H” at the monastery of Saltrey near Cambridge wrote about the experiences of the Irish knight Owein during his visit to Loug Derg: the Tractatus de Purgatorio Sancti Patricii. (Le Goff, 1984). Some forty years before H penned his story, Owein was allowed to enter the cave on the island and soon found himself surrounded by demons and cast into the fire. He was delivered by calling on the name of Christ. After multiple periods of torture, the knight finally made his way across a narrow bridge over Hell and entered an Earthly Paradise, where souls await their entry into heaven. Owein returned to the world to tell others of his ordeal. Various versions and translations of the story became widely read across Europe.

No one knows the source of Owein’s visions. One possibility is that medicinal (“purgative”) herbs were burned in the cave. Some of these could have led to hallucinations. Ireland has evidence of ancient “sweathouses” that were likely used in this way. (Anthony Weir website).

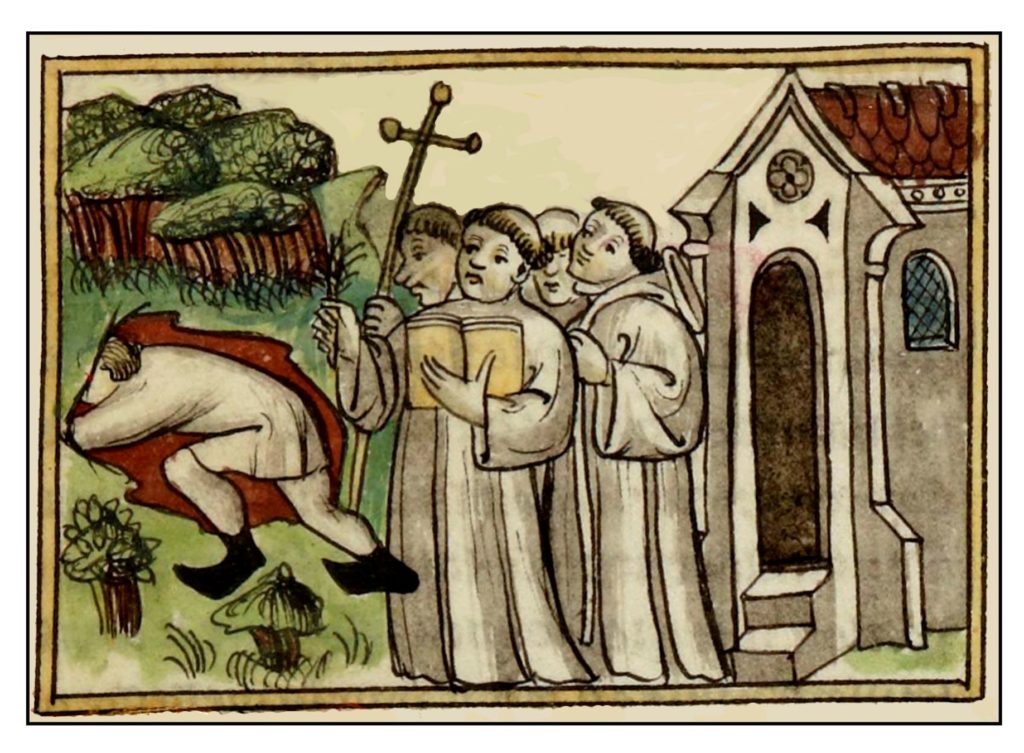

The idea of St Patrick’s Purgatory became famous, and Lough Derg soon became a popular place of pilgrimage. The following illustration, showing a pilgrim entering the cave, is from La tres noble et tres merveilleuse Histoire du purgatoire saint Patrice (14th Century), a manuscript in the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris.

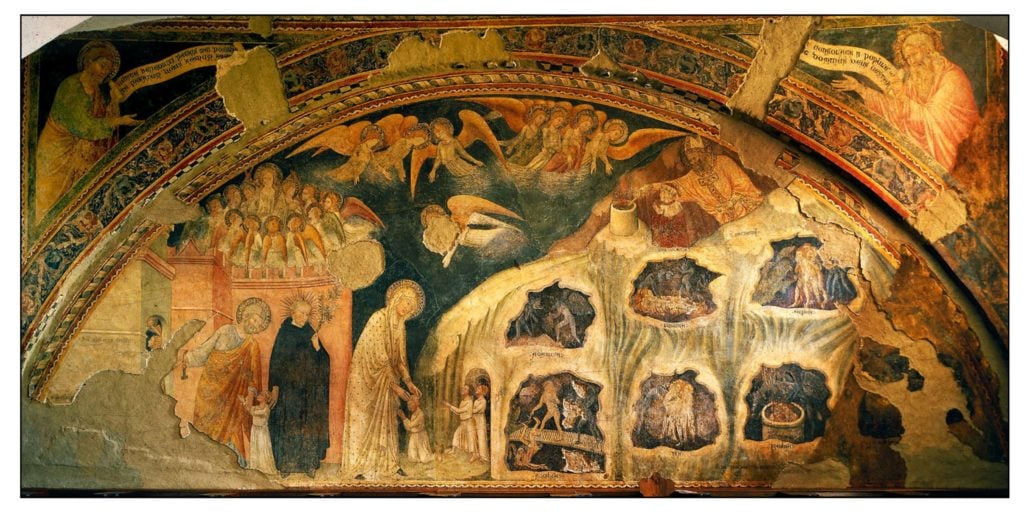

One of the earliest depictions of Purgatory is a fresco in the Convent of San Francisco in Todi, Umbria, Italy (MacTreinfhir, 1986). Whitewashed long ago, this fresco was only restored in 1976. The painter was likely Jacopo di Mino del Pellicciaio, and the date of the fresco is around 1345. Purgatory is shown as a rocky hill filled with separate openings into its hollow center. Above the mountain St Patrick introduces the prayers of the faithful that can help attenuate the sufferings of the souls undergoing purification. In each opening, sinners are tormented by demons and by fire. Each of the seven deadly sins – avarice, envy, sloth, pride, anger, lust, and gluttony – has its own region of purgatory and its own appropriate tortures. For example, in the central upper opening – luxuria (lust) – naked souls lie burning in flames while demons dance upon them. And in the lower right – invidia (envy) – souls are boiled in a seething cauldron.

The purified souls exit Purgatory in the center of the fresco where they are greeted by the Virgin Mary. She places a garland of white flowers upon their heads and passes them to St Philip Benizi (1233 –1285). The building was a monastery for the Order of the Servites before it became a convent and the fresco was clearly painted to glorify Benizi, who had founded this monastic order. The souls are then taken by St Peter into the New Jerusalem to join Christ and his angels. Above the arch are St Matthew on the left and Isaiah on the right. They each have scrolls quoting from their writings:

Come, ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world (Matthew 25:34)

Comfort ye, comfort ye my people, saith your God (Isaiah 40:1).

The Lough Derg Pilgrimage

Pilgrims have visited Lough Derg since the time of St. Patrick. In the early years of the pilgrimage much was made of the experience of Purgatory. However, the church moved away from the idea that Purgatory was an actual place that could be visited, preferring to consider it as a state of existence. Nevertheless, the idea of a pilgrimage to Station Island, as a sacred place conducive of faith and repentance was maintained.

During the subjugation of Ireland by the English in the 17th Century the monastic buildings on Station Island and Saints Island were raised, and the pilgrimage suppressed. Today the only medieval remnants on Station Island are the column supporting St Patrick’s Cross (illustrated on the right) and St. Brigid’s cross, incised in a stone now located in the wall of the modern Basilica. The new Church of St Mary of Angels was built in 1763. In 1790 the cave was filled in and a bell-tower constructed over its remains. The pilgrimage flourished. Various dormitory buildings were built to house the pilgrims. In 1929 St Patrick’s Basilica was constructed: a large octagonal neo-gothic building with extensive stained-glass windows. The illustration below shows a view of the basilica taken from the labyrinth. The following illustration shows the modern island from the air:

The Pilgrimage

The modern pilgrimage to Station Island follows a set course (Good, 2003). The usual visit lasts for 3 days and 2 nights. Pilgrims fast from the midnight before their visit. During their time on the island they partake each day of only one meal, composed of oatcakes or toast with tea or coffee. On their arrival on island, pilgrims give up their shoes and stay barefoot until they leave. On their first night on the island, they remain awake in a vigil in the Basilica of St Patrick. On the second night they sleep in the dormitories.

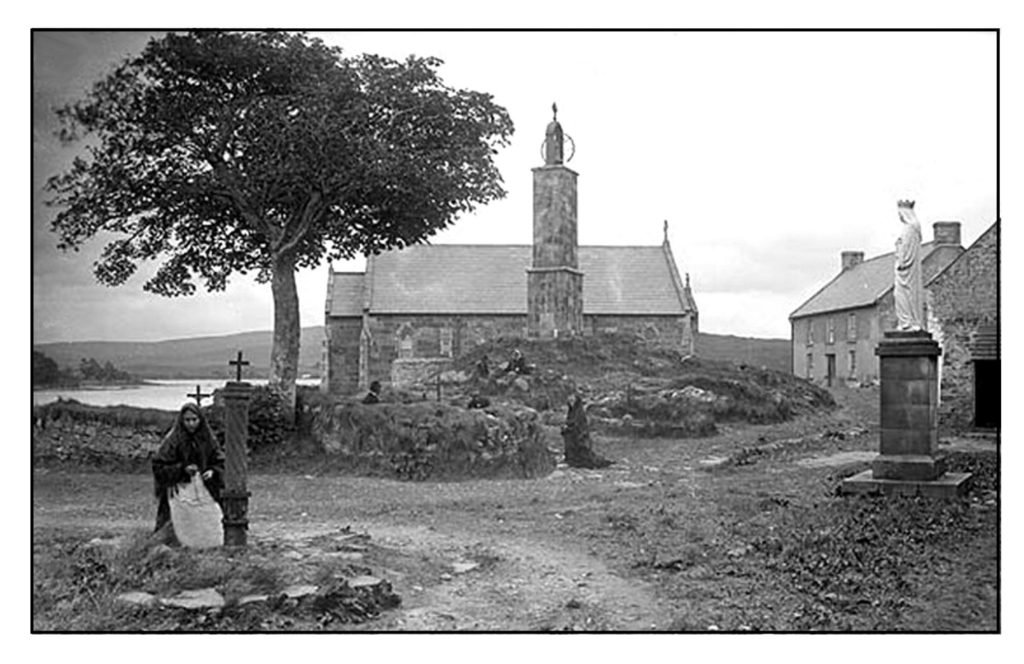

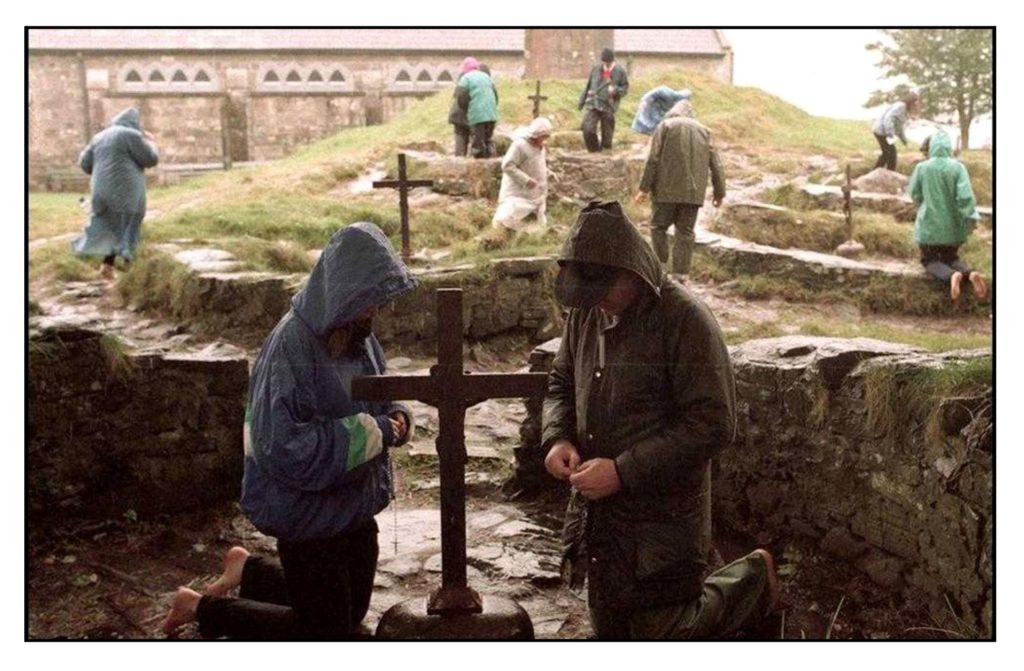

Services are conducted in the basilica. Mass is celebrated 4 times. In addition, a Sacrament of Reconciliation is conducted. Much of the pilgrims’ time on the island involves a sequence of prayers at various locations (“stations”) on the island. The prayers are Lord’s Prayer, the Hail Mary, and the Nicene Creed. Pilgrims begin by praying at St Patrick’s Cross., and then stand at St Brigid’s Cross and renounce the world, the flesh and the devil. After circumambulating the basilica, they then proceed to the “penitential beds,” the remains of the clochans of the original monks on the island. They walk around the beds and then pray at the cross in the center of each bed. Finally, the pilgrims go to the edge of the water to pray and meditate on their baptism and its meaning. The sequence of stations is repeated nine times during the pilgrimage. The following illustrations show pilgrims at the end of the 19th Century in a photograph from the National Library of Ireland and pilgrims from the 21st Century:

Many different writers have described their experience at Lough Derg (O’Brien, 2006). Since participating in the pilgrimage effectively requires that you be Catholic, these writers have all been brought up in the Catholic tradition, and have tried to portray their experience sympathetically. Yet each found that their pilgrimage did not fit easily with their ideals. I shall consider three writers: William Carleton and Patrick Kavanagh briefly, and Seamus Heaney in greater detail.

William Carleton (1794-1869)

William Carleton was born near Clogher in what is now the county Tyrone of Northern Ireland. A monastery was founded there in the 5th Century CE, and the town has long been the seat of a Catholic Bishopric. The youngest of 14 children (8 of whom survived their infancy) of a Catholic tenant farmer, Carleton was taught to read and write in hedge schools. In Ireland at that time the only schools allowed by the government were for children of the Anglican faith. Hedge schools were small illegal schools operated secretly in private houses and barns. They provided a rudimentary education for Catholic children.

In 1813, Carleton made the pilgrimage to Lough Derg. He found the experience oppressive. Soon thereafter gave up his idea of entering the priesthood, and decided to become a writer. His first publication described the pilgrimage. This was initially published in an evangelical Protestant journal and later collected in his Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry. Carleton’s first view of Station Island was dismal:

In the lake itself, about half a mile from the edge next us, was to be seen the “Island”, with two or three slated houses on it, naked and unplastered, as desolate-looking almost as the mountains. A little range of exceeding low hovels, which a dwarf could scarcely enter without stooping, appeared to the left; and the eye could rest on nothing more, except a living mass of human beings crawling slowly about.

He found the vigil and the stations painful and depressing. They provided no release from sin but only intensified one’s self-loathing. He felt no nearness to God.

As for that solemn, humble, and heartfelt sense of God’s presence, which Christian prayer demands, its existence in the mind would not only be a moral but a physical impossibility in Lough Derg. I verily think that if mortification of the body, without conversion of the life or heart — if penance and not repentance could save the soul, no wretch who performed a pilgrimage here could with a good grace be damned. Out of hell the place is matchless, and if there be a purgatory in the other world, it may very well be said there is a fair rehearsal of it in the county of Donegal in Ireland.

Carleton described the lack of Christian charity in the priests of Lough Derg, one of whom insisted on taking the last pennies of a poor pilgrim and his son for a ticket to confession. At the beginning of his pilgrimage Carleton had taken up with two strangely dressed women. At the end these fellow pilgrims stole his coat and his money. Carleton’s experience at Lough Derg challenged his belief in both the Christian Church and his fellow man.

Carleton soon relinquished his Catholicism, travelled to Dublin, studied at Trinity College, and became a Protestant. His conversion is only briefly mentioned in his autobiography (Carleton, 1896, pp 214-5):

One doctrine of the Catholic Church I had sent to the winds long before that period. I allude to exclusive salvation. Neither logic nor reasoning was required to enable me to discard it. Common feeling—the plain principle of simple humanity—was sufficient. This, indeed, was the doctrine which first taught me to feel the justice of thinking for myself; and from that moment I felt that I could not much longer hold the doctrines of a Catholic. This course of thought was not suggested to me by a human being, and to confess the truth, I was a Protestant at least twelve months before the change was known to a human being.

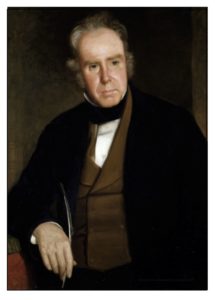

The doctrine of exclusive salvation proposes that only those who believe in Christ can go to heaven; everyone else is damned to Hell. Carleton’s new religion allowed him to become successful, to publish extensively and to marry a Protestant wife. His portrait (illustrated on the left) was painted by John Slattery in the 1850s. Carleton’s pragmatic apostasy has made him a controversial figure in Ireland. However, his approach to religion was probably far more nuanced than his detractors propose. At the end of his life, Carleton was on friendly terms with both priests and preachers. He was offered the last rites of the Catholic Church but respectfully declined (Brown, 1970; Sloan, 2019).

Patrick Kavanagh (1904-1967)

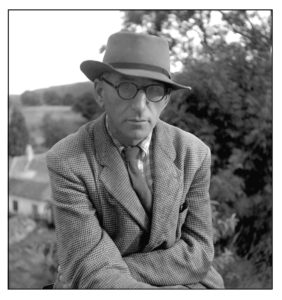

Patrick Kavanagh was born in Inniskeen in County Monaghan, which is now just south of the border with Northern Ireland. He was the 4th of 10 children of a cobbler and farmer. At the age of 27 he left his work as a cobbler with his father and went to Dublin, where he was encouraged by George William Russell, a leader of the Irish Literary Revival. His first book of poems came out in 1936. The photograph on the right was taken by Elinor Wiltshire in 1951 (National Library of Ireland).

In 1942 Kavanagh wrote a long poem describing his experiences during a pilgrimage to Lough Derg. This poem, characterized by verse both free and constrained, was not published until 1978. His pilgrimage became more an exercise in compassion than in penitence (Welch, 1983). At the beginning he is scornful of his fellow pilgrims who are unable to appreciate the beauty of either art or nature:

From Cavan and from Leitrim and from Mayo,

From all the thin-faced parishes where hills

Are perished noses running peaty water,

They come to Lough Derg to fast and pray and beg

With all the bitterness of nonentities, and the envy

Of the inarticulate when dealing with an artist.

Their hands push closed the doors that God holds open.

Love-sunlit is an enchanter in June’s hours

And flowers and light. These to shopkeepers and small lawyers

Are heresies up beauty’s sleeve.

Yet over the course of his poem and his pilgrimage he develops an intense sympathy for the pilgrims. For the generations that they have been exploited by their Protestant landlords. To the extent that they are no longer a who but a what.

‘And who are you?’ said the poet speaking to

The old Leitrim man.

He said, ‘I can tell you

What I am.

Servant girls bred my servility:

When I stoop It is my mother’s mother’s mother’s mother

Each one in turn being called in to spread —

“Wider with your legs,” the master of the house said.

Domestic servants taken back and front.

That’s why I’m servile. It is not the poverty

Of soil in Leitrim that makes me raise my hat

To fools with fifty pounds in a paper bank.

Domestic servants, no one has told

Their generations as it is, as I

Show the cowardice of the man whose mothers were whored

By five generations of capitalist and lord.’

And Kavanagh realized that the grinding poverty of their lives that prevents any hope of gentleness or freedom. One of several sonnets describing the prayers of the pilgrims:

St Anne, I am a young girl from Castleblayney,

One of a farmer’s six grown daughters.

Our little farm, when the season’s rainy,

Is putty spread on stones. The surface waters

Soak all the fields of this north-looking townland.

Last year we lost our acre of potatoes;

And my mother with unmarried daughters round her

Is soaked like our soil in savage natures.

She tries to be as kind as any mother

But what can a mother be in such a house

With arguments going on and such a bother

About the half-boiled pots and unmilked cows.

O Patron of the pure woman who lacks a man,

Let me be free I beg of you, St Anne.

Ford (2011) has suggested that Kavanagh is presenting a God’s-eye view of the pilgrims

The poet’s view of the pilgrims might be seen as an attempt to see them theologically, as God sees them. It is a striking, often paradoxical, mixture of realism and compassion. Again and again the whole group and its individual members are described in their pettiness, selfishness, mediocrity and small-mindedness, their vices of envy, jealousy, greed, smugness, hypocrisy, cold-heartedness and so on, with a special poet’s emphasis on their insensitivity to beauty. Yet again and again there are also glimpses of grace, transcendence, beauty, delight, love, generosity, laughter, compassion and wisdom

Kavanagh ends his poem quietly as the pilgrims depart on the train:

The turnips were a-sowing in the fields around Pettigo

As our train passed through.

A horse-cart stopped near the eye of the railway bridge.

By Monaghan and Cavan and Dundalk

By Bundoran and by Omagh the pilgrims went;

And three sad people had found the key to the lock

Of God’s delight in disillusionment.

Kavanagh realized that he had not changed greatly as a result of the pilgrimage. Nor had his fellows. They had found no greater understanding of God. But perhaps some greater sympathy for each other.

Seamus Heaney (1939-2013)

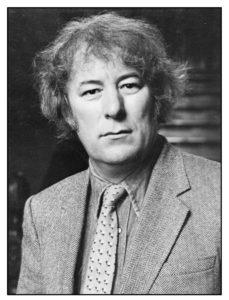

Seamus Heaney was born near Castledawson, County Derry, in Northern Ireland, the first of nine children in his family. His father was a farmer and cattle-dealer. At age 12 Heaney won a scholarship to attend St Coulomb’s College, a Roman Catholic boarding school in Derry. From there he went on to Queen’s University Dublin. His first book of poetry, Death of a Naturalist, was published by Faber and Faber in 1966. Heaney and his family moved to a country cottage in Wicklow in the Republic of Ireland in 1972, and later to Dublin. Heaney spent time teaching at the universities of Berkeley and Harvard in the United States and at Oxford in England. The portrait on the right by Jerry Bauer was taken during one of his sojourns in the United States. In 1995 Heaney was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. He died in 2013; his final words texted to his wife Marie were Noli timere (“Fear not”). Heaney .is buried in St Mary’s Church in the village of Bellaghy near his birthplace. His epitaph quotes from the poem ‘The Gravel Walks’ in The Spirit Level (1996): “Walk on air against your better judgement.”

In 1984 Heaney published a sequence of poems based on an imagined pilgrimage to Station Island in Lough Derg. He had participated in the actual pilgrimage several times when he was a student at Queen’s University (Mulrooney, 2018; O’Driscoll, 2008). As he grew older, however, he became less observant. He found that poetry could provide access to understanding that was more profound and less constrained than religion (Duffy, 2013). In his Nobel lecture Crediting Poetry (1996), he remarked

… for years I was bowed to the desk like some monk bowed over his prie-dieu, some dutiful contemplative pivoting his understanding in an attempt to bear his portion of the weight of the world, knowing himself incapable of heroic virtue or redemptive effect, but constrained by his obedience to his rule to repeat the effort and the posture. Blowing up sparks for meagre heat. Forgetting faith, straining towards good works. Attending insufficiently to the diamond absolutes, among which must be counted the sufficiency of that which is absolutely imagined. Then finally and happily, and not in obedience to the dolorous circumstances of my native place but in despite of them, I straightened up. I began a few years ago to try to make space in my reckoning and imagining for the marvellous as well as for the murderous.

When he was writing the Station Island poems, Heaney was considering Dante and his Divine Comedy (Heaney, 1985). In the Middle Ages Lough Derg had been considered the site of Purgatory. And so Heaney’s Station Island poems are similar in many ways to Dante’s Purgatorio (Fumagalli, 1996; Hawlin 1992). During his imagined pilgrimage the poet sees and talks to various people from his life and from his reading. These visions occur at the prayer stations of the pilgrimage, just like the shades that Dante sees as he ascends through the levels of Mount Purgatory. As in Dante the visions portray the people of his time. Vendler (1998) has suggested that they describe the lives that Heaney might have led given his background. What might have been. Heaney could have become a priest or a teacher; he may have been a victim or a perpetrator of the sectarian violence that permeated Northern Ireland during The Troubles; he may have renounced his religion or accepted it. I shall comment only on some of the poems. More extensive notes are available at the website of David Fawbert, and in critical books (Tobin, 1999; Vendler, 1998) and articles (Conniff, 1999).

The poem begins with the sound of church bells after rain:

A hurry of bell-notes

flew over morning hush

and water-blistered cornfields,

an escaped ringing

that stopped as quickly

as it started. Sunday,

the silence breathed

The bells cease and the first of Heaney’s visions appears: Sweeney, one of the Irish Travellers who camped out near his childhood farm. Sweeney carries a bow-saw to cut firewood from the hedges. His saw appears like a lyre and gives the opening a touch of pagan poetry. But Heaney is soon surrounded and carried away by women on their pilgrimage to Lough Derg.

The next vision comes upon him as he is parked on the road from Pettigo to Lough Derg. The poem has now assumed a form that is a loose version of Dante’s terza rima. He realizes that the “aggravated man” he sees is the ghost of William Carleton, who is upset that nothing has changed: Orangemen and Fenians still hate each other and pilgrims still go to Station Island. He tells Heaney “to try to make sense of what comes,” and leaves with a final piece of wisdom

We are earthworms of the earth, and all

that has gone through us is what will be our trace.’

In the 4th poem Heaney meets with the ghost of Terry Keenan, whom Heaney had known when he was a child and Keenan was a seminarian “doomed to the decent thing.” Keenan had done missionary work in the tropics, contracted a chronic illness, and become disillusioned with his vocation. He had tried to give relief to others but had failed. He asks Heaney what possessed him to take the pilgrimage.

`And you,’ he faltered, ‘what are you doing here

but the same thing? What possessed you?

I at least was young and unaware

that what I thought was chosen was convention.

But all this you were clear of you walked into

over again. And the god has, as they say, withdrawn.

What are you doing, going through these motions?

Unless . . . Unless . . .’ Again he was short of breath

and his whole fevered body yellowed and shook.

`Unless you are here taking the last look.’

Then where he stood was empty as the roads

we both grew up beside, where the sick man

had taken his last look one drizzly evening

when the tarmac steamed with first breath of spring,

a knee-deep mist I waded silently

behind him, on his circuits, visiting.

The poem is in triplets but rhymes only occasionally and not according to the terza rima convention of ABA BCB. The form fits the feeling. The outline of the church’s teaching is there but the words fail.

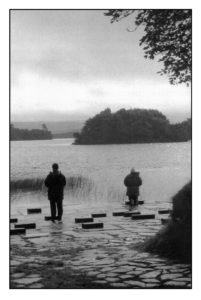

In the seventh poem, Heaney is visited by the ghost of William Strathearn, an old friend from school. They had played together on the same football team. Strathearn had become a shopkeeper. One night in 1977, he was callously murdered by John Weir and Billy McCaughey, two off-duty members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, who incorrectly thought he was a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The terza rima form has returned though the rhyme is more often slant than perfect. The poem begins as Heaney comes to the station near the water’s edge. This is illustrated on right by Anne Cassidy (Good, 2003).

In the seventh poem, Heaney is visited by the ghost of William Strathearn, an old friend from school. They had played together on the same football team. Strathearn had become a shopkeeper. One night in 1977, he was callously murdered by John Weir and Billy McCaughey, two off-duty members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary, who incorrectly thought he was a member of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. The terza rima form has returned though the rhyme is more often slant than perfect. The poem begins as Heaney comes to the station near the water’s edge. This is illustrated on right by Anne Cassidy (Good, 2003).

I had come to the edge of the water,

soothed by just looking, idling over it

as if it were a clear barometer

or a mirror, when his reflection

did not appear but I sensed a presence

entering into my concentration

on not being concentrated as he spoke

my name. And though I was reluctant

I turned to meet his face and the shock

is still in me at what I saw. His brow

was blown open above the eye and blood

had dried on his neck and cheek. ‘Easy now,’

he said, ‘it’s only me. You’ve seen men as raw

after a football match . . . What time it was

when I was wakened up I still don’t know

but I heard this knocking, knocking, and it

scared me, like the phone in the small hours,

so I had the sense not to put on the light

but looked out from behind the curtain. I

saw two customers on the doorstep

and an old landrover with the doors open

parked on the street so I let the curtain drop;

but they must have been waiting for it to move

for they shouted to come down into the shop.

She started to cry then and roll round the bed,

lamenting and lamenting to herself,

not even asking who it was. “Is your head

astray, or what’s come over you?” I roared, more

to bring myself to my senses

than out of any real anger at her

for the knocking shook me, the way they kept it up,

and her whingeing and half-screeching made it worse.

All the time they were shouting, “Shop!

Shop!” so I pulled on my shoes and a sportscoat

and went back to the window and called out,

“What do you want? Could you quieten the racket

or I’ll not come down at all.” “There’s a child not well.

Open up and see what you have got — pills

or a powder or something in a bottle,”

one of them said. He stepped back off the footpath

so I could see his face in the street lamp

and when the other moved I knew them both.

But bad and all as the knocking was, the quiet

hit me worse. She was quiet herself now,

lying dead still, whispering to watch out.

At the bedroom door I switched on the light.

“It’s odd they didn’t look for a chemist.

Who are they anyway at this time of the night?”

she asked me, with the eyes standing in her head.

“I know them to see,” I said, but something

made me reach and squeeze her hand across the bed

before I went downstairs into the aisle

of the shop. I stood there, going weak

in the legs. I remember the stale smell

of cooked meat or something coming through

as I went to open up. From then on

you know as much about it as I do.’

`Did they say nothing?’ ‘Nothing. What would they say?’

`Were they in uniform? Not masked in any way?’

`They were barefaced as they would be in the day,

shites thinking they were the be-all and the end-all.’

`Not that it is any consolation

but they were caught,’ I told him, ‘and got jail.’

Big-limbed, decent, open-faced, he stood

forgetful of everything now except

whatever was welling up in his spoiled head,

beginning to smile. ‘You’ve put on weight

since you did your courting in that big Austin

you got the loan of on a Sunday night.’

Through life and death he had hardly aged.

There always was an athlete’s cleanliness

shining off him and except for the ravaged

forehead and the blood, he was still that same

rangy midfielder in a blue jersey

and starched pants, the one stylist on the team,

the perfect, clean, unthinkable victim.

`Forgive the way I have lived indifferent —

forgive my timid circumspect involvement,’

I surprised myself by saying. ‘Forgive my eye,’

he said, ‘all that’s above my head.’

And then a stun of pain seemed to go through him

and he trembled like a heatwave and faded.

In the next poem Heaney is chided by his cousin Colum McCartney, who died in 1975 as another victim of the sectarian violence in Northern Ireland. Heaney had written a eulogy The Strand at Lough Beg and published this in Fieldwork (1979). The poem quoted from the first canto of Dante’s Purgatorio. Colum is upset that this poem had inappropriately aestheticized the ugliness of his assassination – “saccharined my death with morning due.” Poetry is a way to memorialize what happens but it must not attenuate reality.

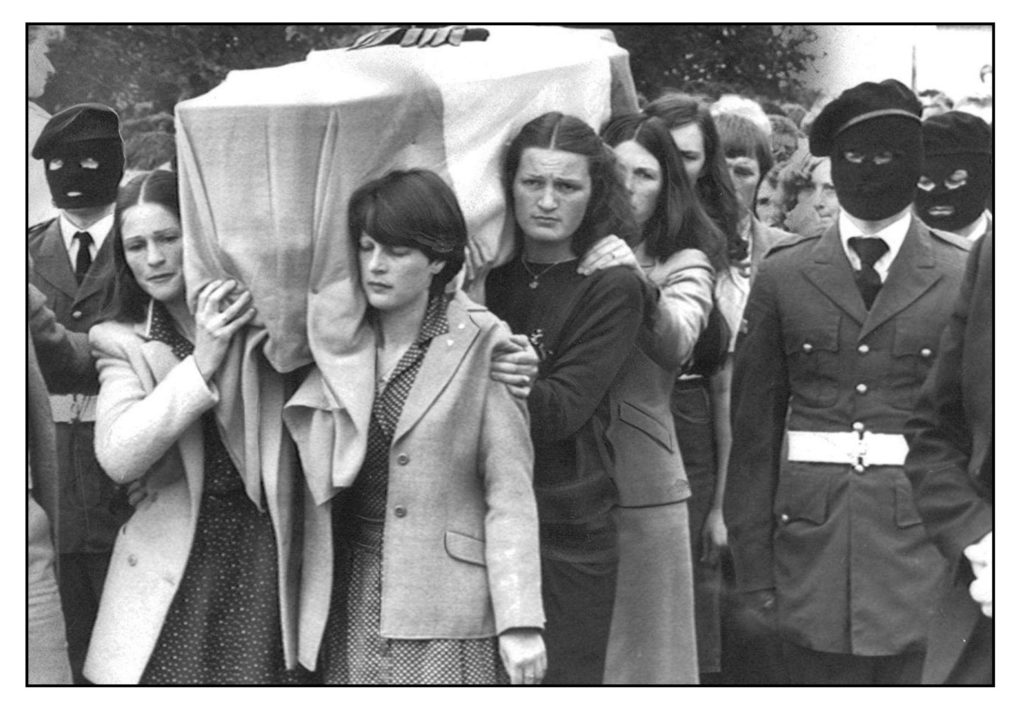

The 9th poem begins with a composite of two of the ten IRA prisoners who died in the hunger strike at the Maze Prison in Belfast in 1981. Francis Hughes, the second of the strikers to die, and Thomas McElwee, the ninth, were both from the village of Bellaghy, close to Heaney’s childhood home. Heaney attended McElwee’s wake. The photograph shows McElwee’s coffin carried by his sisters and attended by an IRA honor guard.

The poem is composed of a sequence of sonnets, of which the first two follow:

The poem is composed of a sequence of sonnets, of which the first two follow:

`My brain dried like spread turf, my stomach

Shrank to a cinder and tightened and cracked.

Often I was dogs on my own track

Of blood on wet grass that I could have licked.

Under the prison blanket, an ambush

Stillness I felt safe in settled round me.

Street lights came on in small towns, the bomb flash

Came before the sound, I saw country

I knew from Glenshane down to Toome

And heard a car I could make out years away

With me in the back of it like a white-faced groom,

A hit-man on the brink, emptied and deadly.

When the police yielded my coffin, I was light

As my head when I took aim.’

This voice from blight

And hunger died through the black dorm:

There he was, laid out with a drift of mass cards

At his shrouded feet. Then the firing party’s

Volley in the yard. I saw woodworm

In gate posts and door jambs, smelt mildew

From the byre loft where he watched and hid

From fields his draped coffin would raft through.

Unquiet soul, they should have buried you

In the bog where you threw your first grenade,

Where only helicopters and curlews

Make their maimed music, and sphagnum moss

Could teach you its medicinal repose

Until, when the weasel whistles on its tail,

No other weasel will obey its call.

The weasel whistle mentioned at the end is an alarm signal. IRA agents used similar-sounding whistle to warn their colleagues.

The penultimate poem of the sequence presents a translation of a poem by the Spanish mystic St John of the Cross (Juan de la Cruz, 1542-1591). St John was from a converso family, that had earlier renounced their Judaism for Christianity. After becoming a priest, he had worked with Saint Teresa of Avila. The posthumous portrait is attributed to Zurbarán (1656). St John’s most famous work is The Dark Night of the Soul, a poem which describes the ascent of the soul to mystical union with God through renunciation of the world.

The translation of the poem Cantar del alma que se huelga de conocer a Dios por fe (“Song of the soul that rejoices in knowing God through faith”) is triggered by the ghost of a monk who had spent time in Spain and who had once served as Heaney’s confessor. We do not know what Heaney had confessed but we sense that it was likely some increasing doubts about his religion. He had become more concerned with poetry than with God. The monk told him to “Read poems as prayers” and “for your penance translate me something by Juan de la Cruz.

The following provides the beginning of the poem in Spanish (Kavanaugh & Rodriguez, 1991) and in Heaney’s translation. Heaney keeps the rhyming of the original though most of his rhymes are slant:

Qué bien sé yo la fonte que inane y corre,

aunque es de noche.

Aquella eterna fonte está escondida,

que bien sé yo do tiene su manida,

aunque es de noche.

Su origen no lo sé, pues no le tiene,

mas sé que todo origen de ella tiene,

aunque es de noche.

Sé que no puede ser cosa tan bella,

y que cielos y tierra beben de ella,

aunque es de noche.

How well I know that fountain, filling, running,

although it is the night.

That eternal fountain, hidden away,

I know its haven and its secrecy

although it is the night.

But not its source because it does not have one,

which is all sources’ source and origin

although it is the night.

No other thing can be so beautiful.

Here the earth and heaven drink their fill

although it is the night.

This poem thus presents the idea that there is something behind the reality of the world, something that can be grasped by religious faith. In Heaney’s thinking it might also be understood through the poetic imagination. In the Coda to Stepping Stones (O’Driscoll, 2008, p 471) he states

Poetry is a ratification of the impulse towards transcendence. You can lose your belief in the afterlife, in the particular judgement at the moment of death, in the eternal separation of the good from the evil ones in the Valley of Jehoshaphat, but it’s harder to lose the sense of an ordained structure, beyond all this fuddle. Poetry represents the need for an ultimate court of appeal. The infinite spaces may be silent, but the human response is to say that this is not good enough, that there has to be more to it than neuter absence. Admittedly we now know that the spaces are far from silent, that they are continuously alive and fluent in their own wordless language, but if you stand out in the country under a starry sky, you can still feel a primitive awe at the muteness of the vault.

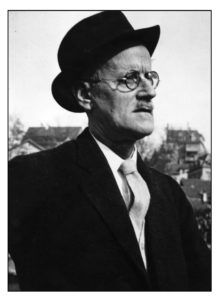

In the twelfth and final poem of the sequence, the ghost of James Joyce appears as Heaney is getting out of the ferry from Station Island and returning to his life. Joyce tells him of his love of words, and how this this gave him freedom (Crowley, 2010). He tells Heaney to forget everything except his writing:

‘Your obligation

is not discharged by any common rite.

What you do you must do on your own.

The main thing is to write

for the joy of it. Cultivate a work-lust

that imagines its haven like your hands at night

dreaming the sun in the sunspot of a breast.

You are fasted now, light-headed, dangerous.

Take off from here. And don’t be so earnest,

so ready for the sackcloth and the ashes.

Let go, let fly, forget.

You’ve listened long enough. Now strike your note.’

It was as if I had stepped free into space

alone with nothing that I had not known

already. Raindrops blew in my face

as I came to and heard the harangue and jeers

going on and on. ‘The English language belongs to us.

You are raking at dead fires,

rehearsing the old whinges at your age.

That subject people stuff is a cod’s game,

infantile, like this peasant pilgrimage.

You lose more of yourself than you redeem

doing the decent thing. Keep at a tangent.

When they make the circle wide, it’s time to swim

out on your own and fill the element

with signatures on your own frequency,

echo soundings, searches, probes, allurements,

elver-gleams in the dark of the whole sea.’

The shower broke in a cloudburst, the tarmac

fumed and sizzled. As he moved off quickly

the downpour loosed its screens round his straight walk.

And so the poems end. Through his imagined pilgrimage to Station Island, Heaney has gained his freedom from Catholicism and from the Troubles. He has been granted the right to his poetry.

References

Brown, T. (1970). The death of William Carleton 1869. Hermathena, 110, 81-85.

Carleton, W. (1834). The Lough Derg pilgrim. From Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry Vol. III. Available at ricorso.net

Carleton, W. (edited and supplemented by D. J. O’Donaghue, 1896). The Life of William Carleton. Volume I. London: Downey & Co. Available at Internet Archive

Conniff, B. (1999). Talking ghosts, living traditions: political violence, Catholicism, and Seamus Heaney’s “Station Island.” Logos, 2, 118-145

Crowley, T. (2010). James Joyce and lexicography: “I must look that word up. Upon my word I must” (Logodaedalus ‘one who is cunning in words’, 1611). Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America, 31, 87-96.

Denzinger, H., Hoping, H., Hünermann, P., Fastiggi, R. L., & Nash, A. E. (2012). Compendium of creeds, definitions, and declarations on matters of faith and morals. 43rd Edition. San Francisco: Ignatius Press

Duffy, E. (2013). Seamus Heaney and Catholicism. In Walker, J. (2013). The present word: Culture, society and the site of literature: Essays in honour of Nicholas Boyle. (pp. 167-183). London: Legenda

Fawbie, D. (accessed 2019) Connecting with Seamus Heaney. Station Island Sequence.

Ford, D. F. (2011). Reading texts, seeking wisdom: A Gospel, a system and a poem. Theology 114, 173–180

Fumagalli, M. C. (1996). “Station Island”: Seamus Heaney’s “Divina Commedia.” Irish University Review, 26, 127-142

Good, E. (with photographs by A. Cassidy, 2003). Lough Derg. Dublin, Ireland: Veritas.

Greenblatt, S. (2001). Hamlet in purgatory. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press.

Griffiths, P. J. (2008). Purgatory. In J. L. Walls (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. (pp. 427-445). Oxford: Oxford University Press

Hawlin, S. (1992). Seamus Heaney’s ‘Station Island’: the shaping of a modern purgatory. English Studies,1, 35-50.

Heaney, S. (1984). Station Island. London: Faber and Faber

Heaney, S. (1985). Envies and identifications: Dante and the modern poet. Irish University Review, 15, 5-19

Heaney, S. (1990). New selected poems, 1966-1987. London: Faber and Faber.

Heaney, S. (1996). Crediting poetry: The Nobel lecture. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. Also available at Nobel Prize website

Heaney, S., (2009). Collected poems (Audio recordings). Dublin: Raidió Teilifís Éireann.

Kavanagh, P. (edited by Quinn, A., 2004). Collected poems. London: Allen Lane.

Kavanaugh, K., & Rodriguez, O. (1991). The collected works of Saint John of the Cross. Washington, D.C: ICS Publications.

Le Goff, J. (1984). The birth of Purgatory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

MacTréinfhir, N. (1986). The Todi Fresco and St. Patrick’s Purgatory, Lough Derg. Clogher Record, 12, 141-158.

Mulrooney, H. (2018). The night of other days: the life and work of poet Seamus Heaney. Bloomington, IN: AuthorHouse

O’Brien, P. (2006). Writing Lough Derg: From William Carleton to Seamus Heaney. Syracuse, N.Y: Syracuse University Press.

O’Driscoll, D. (2008). Stepping stones: interviews with Seamus Heaney. London: Faber & Faber.

Sloan, B. (2019). The dilemma of William Carleton, regional writer and subject of empire. Romance, Revolution and Reform, 1, 92-105.

Tobin, D. (1999). Passage to the center: Imagination and the sacred in the poetry of Seamus Heaney. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky.

Vendler, H. (1998). Seamus Heaney. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Welch, R. (1983), Language as pilgrimage: Lough Derg Poems of Patrick Kavanagh and Denis Devlin. Irish University Review, 13, 54-66

Leave a Reply