This post considers the nature of the human experience of the “numinous:” the sensation that one is the in the presence of something beyond comprehension or control. The term is difficult to define. Other words that overlap in meaning are “sublime,” “sacred” and “transcendent” when referring to the source of the experience, and “awe,” “reverence” and “ecstasy” when describing the state of mind induced.

The numinous is an essential component of religion. However, the scriptures warn that understanding the numinous may not come easily. Verse 71 from the Tao Te Ching (dào dé jīng,The Book of the Way of Virtue) by Lao Tzu claims that

The numinous is an essential component of religion. However, the scriptures warn that understanding the numinous may not come easily. Verse 71 from the Tao Te Ching (dào dé jīng,The Book of the Way of Virtue) by Lao Tzu claims that

zhī bù zhī shàng yǐ

bù zhī zhī bìng yǐ

The Chinese characters go from top to bottom and from right to left. Red Pine (2009) provides a direct translation:

To understand yet not understand

is transcendence

Not to understand yet understand

is affliction

Perhaps the words mean that we should try to understand what we do not know because not to do so leads to suffering. However, I may miss the sense as much as I mar the pronunciation when I try to speak the words.

Meaning of the “Numinous”

The word “numinous” derives from Latin word numen, meaning divinity, often the god or local presiding spirit of a particular place. The word ultimately comes from the Greek neuein for nodding, and may represent the barely perceptible nodding of a divine idol when it approves of being worshipped or grants a wish.

The numinous is essential to religion. William James (1902) suggested that religion

consists of the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto. (p 53)

He further suggested that this might derive from a feeling of being in the presence of something beyond the grasp of our normal five senses:

It is as if there were in the human consciousness a sense of reality, a feeling of objective presence, a perception of what we may call ‘something there,’ more deep and more general than any of the special and particular ‘senses’ by which current psychology supposes existent realities to be originally revealed. (p. 58)

The term “numinous” was first used to describe this feeling by Rudolf Otto (1917). He considered it to be the state of a creature in the presence of its creator:

I propose to call it ‘creature-consciousness’ or creature-feeling. It is the emotion of a creature, submerged and overwhelmed by its own nothingness in contrast to that which is supreme above all creatures (pp. 9-10).

He also described it as the mysterium tremendum – “terrible mystery.” The experience of the numinous varies:

The feeling of it may at times come sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship. It may pass over into a more set and lasting attitude of the soul, continuing, as it were, thrillingly vibrant and resonant, until at last it dies away and the soul resumes its profane, non-religious mood of everyday experience. It may burst in sudden eruption up from the depths of the soul with spasms and convulsions, or lead to the strangest excitements, to intoxicated frenzy, to transport, and to ecstasy. (pp. 12-13).

Otto described five “elements” of the numinous experience. First is “awefulness.” In the monotheistic religions this is also called the “fear of God.” Second is “overpoweringness,” or majestas. This invokes the humility of the creature in the presence of his creator. Third is “urgency.” This is the sense of an active will or living power in charge of the universe. Fourth is the idea that the numinous is “wholly other.” In mysticism this is described as the experience of the void or nothingness. The abyss is a recurring image. The numinous

has no place in our scheme of reality but belongs to an absolutely different one, and which at the same time arouses an irrepressible interest in the mind. (p. 29)

This idea leads to the fifth characteristic of the numinous: “fascination.” The experience entrances as well as bewilders. Otto considered this the Dionysiac element of the numinous, that which we describe as intoxication or ravishment.

C. S. Lewis (1940) used the idea of the numinous to explain how one can believe in God when the existence of suffering makes the concept of an omnipotent and omnibenevolent God illogical. He described the feeling as being in the presence of a mighty spirit:

You would feel wonder and a certain shrinking – a sense of inadequacy to cope with such a visitant and of prostration before it – an emotion which might be expressed in Shakespeare’s words “Under it my genius is rebuked.” This feeling may be described as awe, and the object which excites it as the Numinous. (p. 14).

In recent years, cognitive psychologists have considered the numinous under the rubric of “awe.” This combines cognitive uncertainty and intense emotion (Keltner & Haidt, 2003):

[A]we involves being in the presence of something powerful, along with associated feelings of submission. Awe also involves a difficulty in comprehension, along with associated feelings of confusion, surprise, and wonder.

A final aspect of the numinous that we might consider is the sense that one is being perceived as much as perceiving. This quotation is from Christian Wiman, a poet, in a book called My Bright Abyss (2013):

At such moments it is not only as if we were suddenly perceiving something in reality we had not perceived before, but as if we ourselves were being perceived. (p. 82)

In summary, the experience of the numinous combines three main characteristics

(i) a sense of being in presence of something beyond comprehension or control.

(ii) an intense emotional arousal, combining fear and wonder, like the feeling at the edge of an abyss.

(iii) a state of uncertainty and a need to do something about it.

The Context of Numinous Experiences

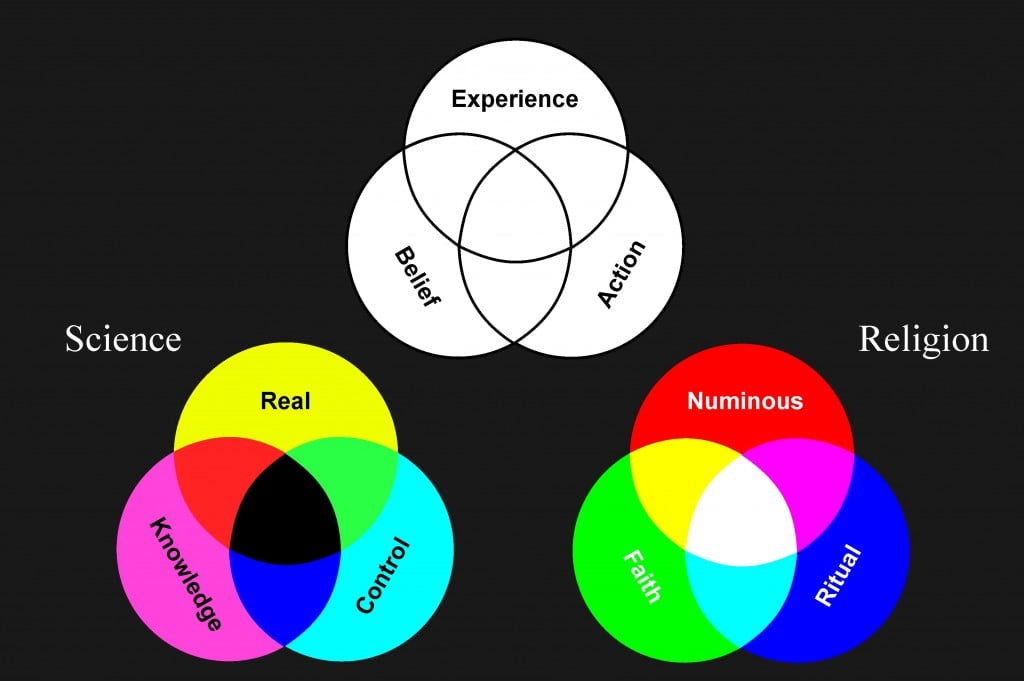

The experience of the numinous parallels the experience of the real world. In general we experience something, derive from that experience a set of beliefs, and then act according to those beliefs in order to gain more experience. This overlapping sequence is illustrated in the following figure, the upper portion of which derives from a similar representation by Lewis-Williams and Pierce (2005, p.25).

When dealing with the real world we create knowledge that then allows us to act within that world. The experience of the numinous leads to faith and faith lead to practices that bring about further interaction with the numinous. For example, revelations can lead to conversion to a faith that promotes prayer and meditation to enhance the experience of the numinous.

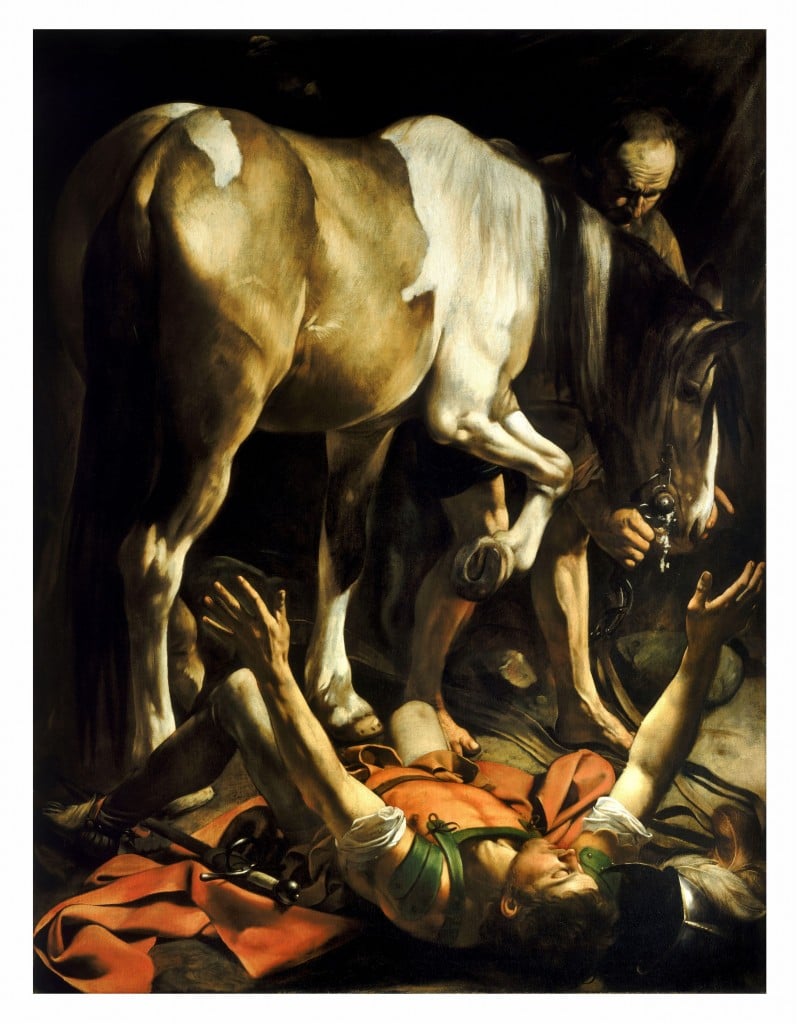

Michelanglo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1601, The Conversion on the Way to Damascus, Church of Santa Maria del Populo, Rome.

An intense experience of the numinous can lead to a complete re-thinking of one’s life. On the road to Damascus the persecutor Saul had a vision that led to him becoming the Apostle Paul:

And it came to pass, that, as I made my journey, and was come nigh unto Damascus about noon, suddenly there shone from heaven a great light round about me.

And I fell unto the ground, and heard a voice saying unto me, Saul, Saul, why persecutest thou me? (Acts 22:6-7)

The nature of Saul’s vision is not known. Some have suggested that it might have been epileptic in origin. Yet the effect is perhaps more important than the cause.

Visions are not as common in our present day as they seemed to in the past. Nowadays, we have only the artistic representation of experiences from earlier times – the numinous at second-hand.

Once a religion is founded, behaviors are promoted to maintain the link to the original numinous experience. The mainstay of the Eastern religions is the process of meditation. The goal is to lose the self, to dissolve into the great sea of being. Western religions tend to prayer more than meditation. Communing with a personal God rather than dissolving in a Universal Force.

Though mainly peaceful, both prayer and meditation can become ecstatic. Saint Teresa’s experience of the angel was as sexual as it was ascetic:

I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God (Teresa of Avila, 1581, 29:17).

The numinous is not necessarily related to religion. The romantic revolution led to the search for the numinous in nature, often described as the “sublime:”

And I have felt

A presence that disturbs me with the joy

Of elevated thoughts; a sense sublime

Of something far more deeply interfused,

Whose dwelling is the light of setting suns,

And the round ocean and the living air,

And the blue sky, and in the mind of man;

A motion and a spirit, that impels

All thinking things, all objects of all thought,

And rolls through all things.

Lines Written a Few Miles above Tintern

Abbey, William Wordsworth, 1798

The term “sublime” has multiple meanings (Saint-Girons, 2014). In the context of Wordsworth’s poem it is used in the manner of Burke in his to mean something that evokes both terror and delight.

Whatever is fitted in any sort to excite the ideas of pain, and danger, that is to say, whatever is in any sort terrible, or is conversant about terrible objects, or operates in a manner analogous to terror, is a source of the sublime; that is, it is productive of the strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling. When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances, and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience. (pp. 13-14).

The numinous can come from drugs as well as devotion. Wordsworth’s friend Coleridge’s visions of Kubla Khan were induced by opium. In the latter half of the twentieth century psychedelic experiences became a common way to seek the numinous:

Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin’ ship

My senses have been stripped, my hands can’t feel to grip

My toes too numb to step, wait only for my boot heels

To be wanderin’

I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade

Into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way

I promise to go under it.

Bob Dylan, Mr Tambourine Man, 1967

The near-death experience is another way to the numinous.The anoxic brain is likely awash in psychodelic chemicals. Yet, there is no doubt of the experience, or the memory of an ascent toward the light.

Numinous experiences of whatever kind tend to make people change their thinking. This can lead to a religious belief system or faith. Faith fosters practices, such as meditation, prayer, and asceticism, that promote further numinous experiences.

Psychological Studies of the Numinous Experience

Keltner and Haidt (2003) reviewed our understanding of awe. Many different situations can elicit the mental state. We may awed in the presence of great natural beauty – sunsets, mountains, canyons, galaxies. Artistic creations can also elicit awe – paintings especially when large, music especially when loud, architecture especially when high. Great leaders and saints can trigger awe and devotion. Science can also bring forth the feeling – the ecstasy of theory rather than theology.

Awe has both emotional and cognitive characteristics. The two main emotions in the experience of awes are fear and wonder. Essential to the experience of awe is an incomplete understanding of what we are experiencing. The vastness of what we perceive overwhelms our cognitive ability. There is a pressing need to come to grips with the source of our confusion and uncertainty.

[A]we involves a need for accommodation, which may or may not be satisfied. The success of one’s attempts at accommodation may partially explain why awe can be both terrifying (when one fails to understand) and enlightening (when one succeeds).

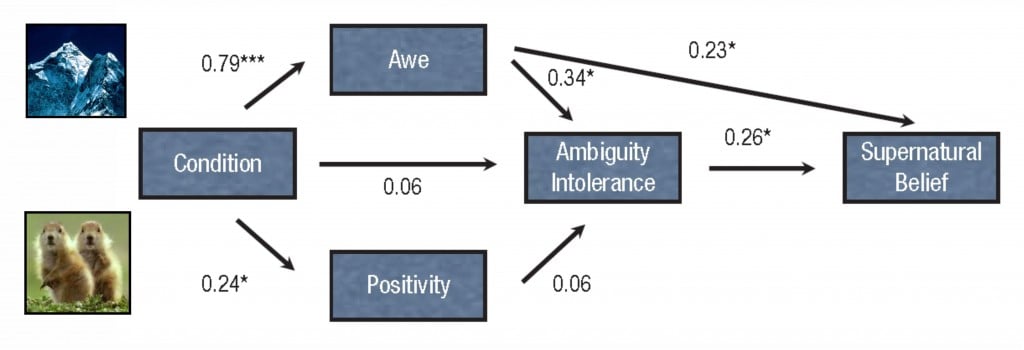

The experience of the numinous often leads to a belief in supernatural powers. A recent psychological study by Valdesolo and Graham (2014) investigated how this comes about. Subjects were exposed to two conditions. In one they watched awe-inspiring videos of sunsets, mountains, canyons and galaxies. In another they watched humorous videos of animal behavior. Their emotional experience (awe, positivity or neutral) was quantified using simple scales.

Two questionnaires were administered. One determined the subject’s ability to tolerate uncertainty: “I feel uncomfortable when I don’t understand the reason why an event occurred in my life” Another determined the subject’s belief in supernatural forces: “The events that occur in this world unfold according to God’s or some other nonhuman entity’s plan.” A correlational analysis showed that awe induced by the experimental manipulation increased belief in supernatural forces in those that were less able to tolerate ambiguity.

The authors suggest that “in the moment of awe, some of the fear and trembling can be mitigated by perceiving an author’s hand in the experience.” In a related experiment, Kristin Laurin and her colleagues (2008) related the belief in God to the “desire to avoid the emotionally uncomfortable experience of perceiving the world as random and chaotic.” God is what we postulate to make the world make sense and to provide us comfort in the face of deep emotions.

The numinous induces emotional as well as cognitive effects. However, we understand much less about our emotions than about our thoughts. The complex array of human emotions can be considered as mixtures of some primary states. Six basic emotions generally considered: happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, and disgust. Other emotions were considered as combinations of these primary states. Thus hatred may be a combination of anger and disgust. In a recent paper describing computer algorithms for recognizing human emotions from facial expressions, Du and his colleagues (2014) have suggested that awe is a combination of surprise and fear.

Awe may be more complex. The experience of the numinous involves attraction as well as withdrawal: orientation toward as well as flight from, heart rate slowing as opposed to speeding. The mysterium tremendum is often also considered the mysterium fascinans.

Some categorizations of emotion include curiosity: that which leads us to explore our environment. Curiosity (or “interest”) is an emotional state, personality trait or motivational drive that becomes manifest in a situation where there is either a lack of arousal (boredom) or a disparity between what one experiences and what one understands (information-deprivation) (Litman, 2005). Curiosity is prominent in children. The main facial aspects of curiosity are the fixed stare, widened eyelids and pursed lips (Reeve, 1993).I suggest that the numinous induces curiosity as well as fear and uncertainty.

Some categorizations of emotion include curiosity: that which leads us to explore our environment. Curiosity (or “interest”) is an emotional state, personality trait or motivational drive that becomes manifest in a situation where there is either a lack of arousal (boredom) or a disparity between what one experiences and what one understands (information-deprivation) (Litman, 2005). Curiosity is prominent in children. The main facial aspects of curiosity are the fixed stare, widened eyelids and pursed lips (Reeve, 1993).I suggest that the numinous induces curiosity as well as fear and uncertainty.

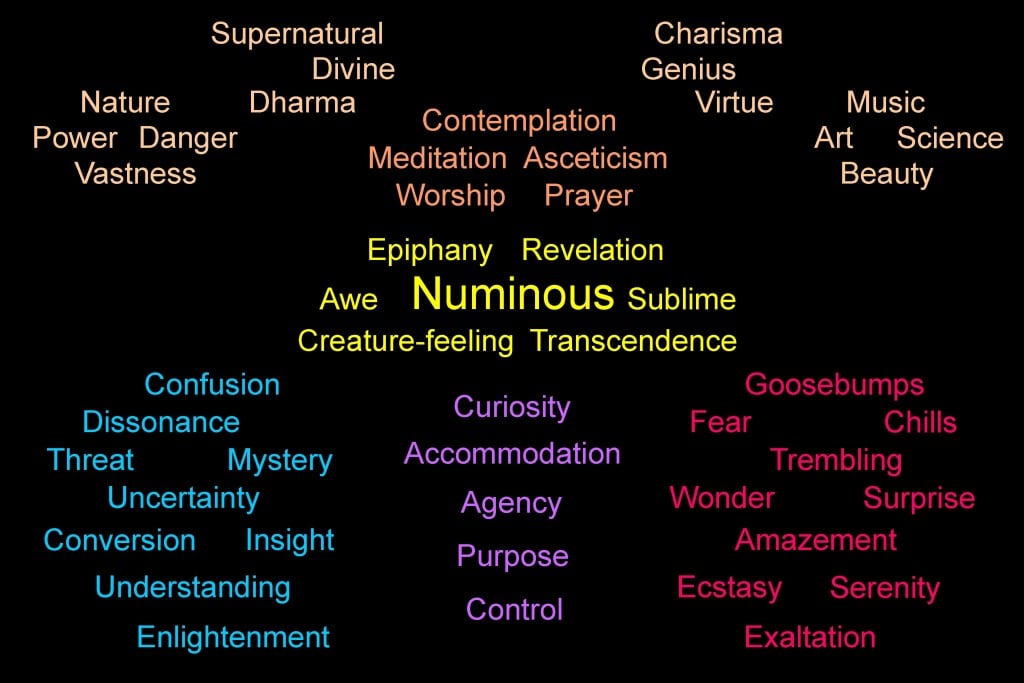

The numinous is difficult to describe – indeed it is often called ineffable, that which passes understanding. In the dark night of the soul a cloud of words appears as a possible summary of the psychology of the numinous:

The experience of the numinous can be induced (pale yellow) by natural beauty, by supernatural effects, by charismatic people and by works of art. It can be fostered by various religious behaviors (orange). The numinous induces both cognitive and emotional responses. The main cognitive effects (blue) are confusion and uncertainty. The main emotional effects (light red) are fear and wonder. We must try to cope with these effects through processes of accommodation (purple) so that we might reach enlightenment and exaltation.

Neuroscientific Studies of the Numinous

Unfortunately, we have not been able to determine specific brain concomitants of the numinous experience. Many regions are active and these interact in as yet unknown ways. The three main areas are the prefrontal regions, especially those active during the processing of theory of mind, the temporal regions, especially those related to emotions, and the parietal regions, where different perceptual modalities come together.

Neurological approaches to the numinous have involved studies of both epilepsy and brain lesions. The numinous experience may be part of the aura of an epileptic attack. Fyodor Dostoyevsky suffered from epilepsy, and we presume that the seizures of Prince Myshkin in The Idiot reflect his own experience:

His mind, his heart were lit up with an extraordinary light; all his agitation, all his doubts, all his worries were as if placated at once, resolved in a sort of sublime tranquility, filled with serene harmonious joy, and hope, filled with reason and ultimate cause.

Although the origin of Dostoyevsky’s seizures is unknown, most consider them as temporal lobe epilepsy. Surveys show that about 4 % of patients with temporal lobe epilepsy have religious or mystical experience either in the aura or in the post-ictal state (Devinsky & Lai, 2008). The experience is much more likely pleasant than not.

Attempts to trigger the numinous experience in normal subjects by magnetic stimulation of the temporal lobe (Persinger, 2002) have not been replicated (Granqvist et al., 2005). The stimulus levels were likely too low to have any neuronal effect, and the numinous experiences reported were probably related to suggestion rather than to stimulation.

Olaf Blanke and his colleagues (2004) studied five patients who reported out-of-body experiences and found lesions in the temporo-parietal region of the brain. This region where the different perceptual systems come together may be important in the representation of the self within a world. Losing oneself and becoming swept away in a more universal experience may therefore result from damage to these regions. This area of the cortex is very sensitive to anoxia since it is at the furthest reaches of the cortical vascular supply. Some have suggested that the prophets who received divine revelations when they went up into the mountains might have been particularly susceptible to hypoxia (Arzy et al., 2005). A similar hypothesis can be made for the near-death experience.

The electrical activity of the human brain changes markedly during the numinous experience. Both alpha and theta activity significantly increase during meditation (e.g. Cahn & Polich, 2006; Cahn et al., 2013; Tsai et al, 2013). The problem is that we do not really know what these rhythms mean in terms of brain processing. Furthermore, we do not know whether the rhythmic changes are an essential part of the meditation process or simply a side-effect. The alpha rhythm is likely an idling activity generated when the visual cortex is not processing information. Theta activity can occur in drowsiness and in emotional arousal. In the sixties, seekers of the numinous trained their brains to increase their alpha rhythm. Whether or not such biofeedback brought forth revelations independently of the pharmaceuticals that were its frequent concomitants remains unknown. As well as changing the ongoing EEG rhythms, meditation also alters the electrical activity evoked or induced by external stimuli (Cahn et al., 2013). Again we have difficulty determining what this means for the meditative state because we do not really know what these changes indicate.

Functional MRI studies of the numinous experience are difficult. Mystic visions may not come easily in a multi-Tesla magnetic field. Many experiments have occurred and many manipulations have been made (a non-critical review is Fingelkurts & Fingelkurts, 2009). Some studies are woefully inadequate in terms of their design and analysis. Others are intriguing but founder on the difficulty of setting up experimental manipulations that can lead to a sense of the numinous within the confines of the magnet. Two sets of studies illustrate the problems.

Beauregard and his colleagues studied Carmelite nuns as they recalled mystical experiences (Beauregard et al., 2006, 2008). They found multiple regions active in comparison to the resting state, most prominently in the inferior frontal, temporal and parietal regions.

Kapogiannis and his colleagues used a much less effective manipulation – subjects either evaluated religious statements or discriminated fonts (Kapogiannis et al., 2009, 2014). Their only significant finding related to a belief in God’s lack of involvement in the world. The brain only betrayed its lack of faith.

Perhaps the numinous is in the interactions of networks rather than the activity of neurons. Brain connectivity is likely as important as brain activity (Yeo et al., 2011). A recent study of meditation by Xu and his colleagues (2014) showed activity mainly in the default, frontoparietal, and limbic networks. The default network involving frontal, parietal and temporal regions is typically active during resting control conditions when the brain is not involved in the experimental task. Intriguingly, the default network was more active during meditation than during the normal resting state. Perhaps the default mode of the human cerebral cortex allows the experience of the numinous, at least in the sense of the brain freely thinking without external constraint. When we withdraw from the world and look inward, our thoughts often turn to matters of philosophy. As Alfred North Whitehead (1926) said “Religion is the art and theory of the internal life of man.”

Overview

Although the numinous experience is the focus of scripture and the basis for religious belief, we have little knowledge of how it occurs. We have some understanding of the psychology that underlies the experience. Emotions of fear and wonder combine with a cognitive state of confusion and uncertainty. The outcome of the experience can be some accommodation of our thinking to allow a larger view of the world. We know very little about how the brain mediates the numinous experience. This is unfortunate since it is so important. It is what changes lives.

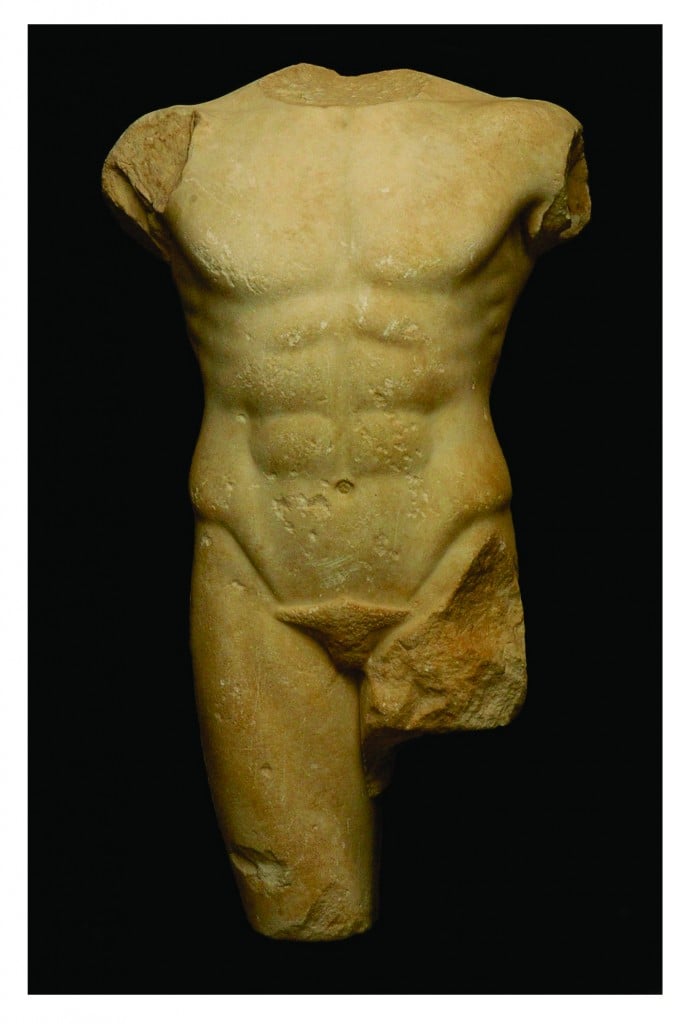

Rainer Maria Rilke wrote about his experience of the numinous while looking at a torso of Apollo in the Louvre. His poem Archaïscher Torso Apollos (Rilke, 1908) concludes:

denn da ist keine Stelle,

die dich nicht sieht. Du mußt dein Leben ändern.

for there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

References

Arzy, S., Idel, M., Landis, T., & Blanke, O. (2005) Why revelations have occurred on mountains? Linking mystical experiences and cognitive neuroscience. Medical Hypotheses, 65, 841–845

Blanke, O., Landis, T., Spinelli, L., & Seeck, M. (2004). Out-of-body experience and autoscopy of neurological origin. Brain, 127, 243–258.

Beauregard, M., & Paquette,V. (2006). Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns. Neuroscience Letters, 405, 186–190.

Beauregard, M., & Paquette,V. (2008). EEG activity in Carmelite nuns during a mystical experience. Neuroscience Letters, 444, 1-4

Burke, E. (1757). A philosophical enquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and beautiful. London: R. and J. Dodsley.

Cahn, B. R., & Polich, J. (2006). Meditation states and traits: EEG, ERP, and neuroimaging studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 180–211.

Cahn, B. R., Delorme, A., & Polich, J. (2013). Event-related delta, theta, alpha and gamma correlates to auditory oddball processing during Vipassana meditation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8, 100-111.

Devinsky, O., & Lai, G. (2008). Spirituality and religion in epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 12, 636–643

Dostoyevsky, F. (1869, translated by Pevear, R., & Volokhonsky, L., 2002). The idiot. New York: Everyman’s Library. (Part II Chapter V, pp. 225-226).

Du, S., Tao, Y., & Martinez, A. M. (2014). Compound facial expressions of emotion. Proceedings National Academy Sciences (USA), 111, E1454–E1462.

Fingelkurts, A. A., & Fingelkurts, A. A. (2009). Is our brain hardwired to produce God, or is our brain hardwired to perceive God? A systematic review on the role of the brain in mediating religious experience. Cognitive Processing, 10, 293-326.

Granqvist, P., Fredrikson, M., Unge, P., Hagenfeldt, A., Valind, S., Larhammar, D., & Larsson, M. (2005). Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak complex magnetic fields. Neuroscience Letters, 379, 1–6.

James, W. (1902). The Varieties of Religious Experience. New York: Longmans, Green and Company. (Lecture III: The Reality of the Unseen)

Kapogiannis, D., Barbey, A. K., Su, M., Zamboni, G., Krueger, F., Grafman, J. (2009). Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science U S A, 106, 4876-4881.

Kapogiannis, D., Deshpande, G., Krueger, F., Thornburg, M. P., & Grafman, J. H. (2014). Brain networks shaping religious belief. Brain Connectivity, 4, 70-79.

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition & Emotion, 17, 297–314.

Laurin, K., Kay, A. C., & Moscovitch, D. A. (2008). Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44, 1559–1562.

Lewis, C. S. (1940, reprinted 1977). The Problem of Pain. London: Harper Collins (Fount). (p. 14).

Lewis-Williams, J. D., & Pearce, D. G. (2005). Inside the Neolithic mind: Consciousness, cosmos, and the realm of the gods. London: Thames & Hudson.

Litman, J.A. (2005). Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cognition and Emotion, 19, 793-814.

Otto, R. (1917, translated 1923 by J.W. Harvey). The Idea of the Holy. An inquiry into the non-rational factor in the idea of the divine and its relation to the rational. London: Oxford University Press.

Persinger, M. A. (2002). Experimental simulation of the God experience.: implications for religious beliefs and the future of the human species. In R. Joseph (Ed.) Neurotheology: Brain, Science, Spirituality, Religious Experience. (pp. 267-284). San Jose, CA: University Press.

Red Pine (2009). Lao-tzu’s Taoteching: with selected commentaries of the past 2,000 years. Port Townsend, WA: Copper Canyon Press.

Reeve, J. (1993). The face of interest. Motivation and Emotion, 17, 353-375.

Rilke, R. M. (1908). Der neuen Gedichte anderer Teil. Leipzig: Insel.

Teresa of Avila, Saint (1581, translated D. Lewis, 1904). The Life of St. Teresa of Jesus, of the Order of Our Lady of Carmel. 3rd Edition. London: Thomas Baker. (Available online through Christian Classics Ethereal Library).

Saint-Girons, B. (2014). Sublime. In B. Cassin (Ed.) Dictionary of untranslatables: a philosophical lexicon. (pp. 1091-1096). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tsai, J. F., Jou, S. H., Cho, W. C., & Lin, C. M. (2013). Electroencephalography when meditation advances: a case-based time-series analysis. Cognitive Processing, 14, 371–376.

Valdesolo, P., & Graham, J. (2014). Awe, uncertainty, and agency detection. Psychological Science, 25, 170-178

Whitehead, A. N. (1926). Religion in the making. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (pp. 47-48)

Wiman, C. (2013). My bright abyss. Meditation of a modern believer. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Wordsworth, W., & Coleridge, S. T. (1798). Lyrical ballads with a few other poems. London: J. & A. Arch.

Xu, J., Vik, A., Groote, I. R., Lagopoulos, J., Holen, A., Ellingsen, O., Håberg, A. K., & Davanger, S. (2014). Nondirective meditation activates default mode network and areas associated with memory retrieval and emotional processing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8:86.

Yeo, B. T., Krienen, F. M., Sepulcre, J., Sabuncu, M. R,, Lashkari, D., Hollinshead, M., Roffman, J. L., Smoller, J. W., Zöllei, L., Polimeni, J. R., Fischl, B., Liu, H., & Buckner, R. L. (2011). The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. Journal of Neurophysiology, 106, 1125-1165.

Hi Terry, I found this a very interesting article.

As you say, “We know very little about how the brain mediates the numinous experience. This is unfortunate since it is so important. It is what changes lives.”

I wonder how common such experiences are? Some snippets of evidence make me suspect that they are quite common. The faithful seem to treat such experiences as being objectively real, beyond any doubt.

How often the experience of the numinous occurs will of course depend on how it is defined. I think that awe as described by Keltner and Haidt (2003) – combining the perception of vastness with a need for understanding – probably occurs in everybody at some time. Human beings are small and the universe is large. The frequency and the intensity of the experiences will vary from one individual to the next. How a person copes with the experiences will depend upon his or her psychological makeup and upon the social context. Some will interpret the experiences in terms of a higher power; others will be driven to understand the experiences in terms of physical laws; others may enjoy the experiences because they are incomprehensible and will not seek interpretation. Religions promote behaviors, such as prayer and meditation, that can facilitate the experience of awe.

I agree with you that the experience is clearly real. Furthermore, it can often be considered “objective” in that it comes from outside and is not internally driven. The interpretation of the source varies, but the experience does push the individual to seek its meaning. Western religious traditions promote the idea of epiphany – the revelation of a higher power. Eastern traditions foster the idea of insight –the union of individual with universal.

Well here is a reply nearly ten years later. I have been revisiting an experience that happened to me tweleve years ago. I have thought about it often. For the sake of brevity I will call it a vision. In the years since I have tried to understand it. I have revisited the experience today, that is thought about it. And did some reading on the web. And rather suddenly I realize there is nothing to integrate, interpret, analyze. The experience was instantly integrated: it changed my life literally overnight. Overnight the direction of my life was changed. There is nothing more to understand: it happened and it profoundly changed me. I think what impels me to get a better understanding comes from the very nature of the experience. It is inexplicable. It was shockingly real. To the modern mind it needs explanation…Reading your essay helped me to realize, Yes, it is exactly what I experienced it to be, mysterious, terrifying,life altering, mind altering. I don’t need insight into how to integrate it. Your telling of the story of Saul on the road to Damascus crystalized this understanding for me. It happened, it was shocking and it changed me.

I appreciate your writing on this subject

Many thanks for your comment. You describe things very well. The numinous experience is indeeed mysterious. Somehow it excites many different ideas in the brain. And as the excitement settles, one’s view of life is changed.