With my surname it is inevitable that I should become interested in the Picts, a people who lived in Scotland during the first millennium of the Common Era. They left behind many sculptured stones, which now stand in fields and churchyards in the Northeast part of Scotland. Together with the Scots, the Vikings and the Anglo-Saxons, they became the people of Scotland.

Origins of the Picts

The British Isles have been home to human beings for thousands of years. In the Neolithic Period, the inhabitants of Western Britain, Northern Britain and Ireland raised striking stone monuments, the most famous of which is Stonehenge. Scotland has numerous stone-circles and standing stones, particularly in the West and North. The illustration at the right shows a Neolithic standing stone (about 3 meters high) at Drumtroddan in Galloway. Most Neolithic stones are plain, but occasionally they are marked with circular incisions or hollowed-out cups.

Recent archeological evidence has indicated a major change in the people of Britain during the 3rd Millennium BCE. At that time the original Neolithic inhabitants of the islands were largely replaced by Bronze Age people from the continent who brought with them the technology of Bell-Beaker pots (Olalde et al., 2018). This migration to Britain was part of the westward expansion of the Celtic peoples (Manco, 2015; Cunliffe, 2018).

The beakers were molded by hand rather than on a wheel, and had a characteristic bell shape (Clarke, 1966). They were decorated horizontally either by cord impressions or by incised patterns. Typical pots had a diameter of about 10 cm and were used for drinking. Larger pots could be used for storage or as funeral urns. Some pots were used in the smelting of metals. The bell-beaker technology began in central Europe but there was much interchange of both pots and potters among the different peoples and regions of Europe (Salanova et al., 2016). The illustration shows a Spanish pot on the left and a Scottish pot on the right:

The people who brought the beakers from the continent to Britain likely spoke an Indo-European Proto-Celtic language. This then differentiated into two main branches – Goedelic in Ireland (and later in Western Scotland) and Brythonic in Britain. Goedelic developed into Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic; Brythonic developed into Brittonic, Cornish, Welsh and Pictish.

The Celts thrived on the British Isles until the Romans came. Julius Caesar made his first forays into Britain in 55 BCE, and Roman legions subsequently controlled much of Southern Britain. Boudicca led an uprising of the Britons in 60 CE, but this was soon put down. Gnaeus Julius Agricola, governor of the Roman Province of Britannia from 77 to 85 CE, expanded the area of Roman control northward. He led his soldiers against the inhabitants of what is now called Scotland, culminating in 83 CE in the Battle of Mons Graupius (somewhere in Aberdeenshire). The Romans considered themselves victorious. Agricola’s nephew Tacitus (98 CE, pp 218-239) described the battle, attributing to the Pictish general Calgacus a rousing speech of defiance before the fighting:

But today the uttermost parts of Britain are laid bare; there are no other tribes to come; nothing but sea and cliffs and these more deadly Romans, whose arrogance you shun in vain by obedience and self-restraint. Harriers of the world, now that earth fails their all-devastating hands, they probe even the sea; if their enemy have wealth, they have greed; if he be poor, they are ambitious; East nor West has glutted them; alone of mankind they behold with the same passion of concupiscence waste alike and want. To plunder, butcher, steal, these things they misname empire; they make a desolation and they call it peace. … Here you have a general and an army; on the other side lies tribute, labour in the mines, and all the other pangs of slavery. You have it in your power to perpetuate your sufferings for ever or to avenge them to-day upon this field; therefore, before you go into action, think upon your ancestors and upon your children.

Tacitus described the outcome as a “decisive victory’ for the Romans. However, Agricola returned to the south without leaving any occupying garrisons. The Romans later set up defensive walls to keep out the marauding highlanders: Hadrian’s Wall (122 CE) at the level of the Firth of Solvay and a far less effective Antonine Wall (142 CE) at the level of the Firth of Forth. The sculptured Bridgeness slab in the Antonine Wall, showing a Roman horseman trampling on the Picts, may perhaps refer to Mons Graupius.

The warriors north of the walls were called Scots and Picts by the Romans. The term Scots is of uncertain etymology. It was initially used to describe raiders from Ireland but it later came to mean those Celts in the Western part of Scotland who were related by language and trade to the Irish. The Picts were in the North East. Their name, deriving from picti (painted), refers to their custom of painting or tattooing their bodies, a custom shared with the Celts in the more Southern regions of Britain. We have little if any knowledge of the Pictish language, but it was likely more related to the Brittonic language than the Gaelic spoken by the Scots.

When the Roman Empire crumbled in the 5th Century CE, the province of Britannia was invaded by the Anglo-Saxons. The Celts were driven westward to Wales and Cornwall. Several new kingdoms were set up, most notably Mercia in the middle of England and Northumbria in the Northeast. In the 9th Century the Vikings attacked the British Isles, later settling and governing many northern regions of both Britain and Ireland. .

Pictish History

Most of what we know about the Picts comes from historians who were not Picts. Most of these wrote long after the events they described. There are lists of Pictish kings (e.g., Clarkson, 2017, pp 207-208) but these are difficult to follow. Pictish kings were often not succeeded by their sons. This may have been due to matrilineal succession (Woolf, 1988), but was more likely caused by the kingship switching among the feuding clans. For the purposes of this posting on the sculptured stones I can highlight three main events in Pictish History after the Romans left.

First was the coming of Christianity. In the 6th Century CE, St. Columba came from Ireland to Scotland. At that time, the Gaelic people in Western Scotland were loosely affiliated in the Kingdom of Dal Raita. In 563 CE, their king, Connall mac Comgaill, granted St. Columba the island of Iona, on which to build a monastery. Once the monastic community was established Columba moved to proselytize the Picts. In 565 CE, Columba visited the stronghold of Brude (or “Bridei”), son of Maelchon. No one is clear as to its location, perhaps Craig Phadraig near Inverness. According to Adamnan’s Life of Columba (Book II:38)

[W]hen the saint made his first journey to King Brude, it happened that the king, elated by the pride of royalty, acted haughtily, and would not open his gates on the first arrival of the blessed man. When the man of God observed this, he approached the folding doors with his companions, and having first formed upon them the sign of the cross of our Lord, he then knocked at and laid his hand upon the gate, which instantly flew open of its own accord, the bolts having been driven back with great force. The saint and his companions then passed through the gate thus speedily opened. And when the king learned what had occurred, he and his councillors were filled with alarm, and immediately setting out from the palace, he advanced to meet with due respect the blessed man, whom he addressed in the most conciliating and respectful language. And ever after from that day, so long as he lived, the king held this holy and reverend man in very great honour, as was due.

The recorded lives of the saints are ornamented with miracles. The opening of the door likely had some more natural cause, but the beginning of the conversion of the Picts can be dated to about this time. An 1898 mural in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery by William Hole shows Saint Columba’s mission to the Picts:

A second major event in Pictish history was the Battle of Dun Nechtain in 685 CE (Hudson, 2014, pp 74-80; Clarkson, 2017, pp 121-137). Under the leadership of King Bridei mac Bili (also known as Brude), the Picts defeated a Northumbrian army led by King Ecgfrith. According to Bede (8th Century, Book IV: 26), this was a divine punishment for the Northumbrian incursions into Ireland:

In the year of our Lord’s incarnation 684, Egfrid, king of the Northumbrians, sending Beort, his general, with an army, into Ireland, miserably wasted that harmless nation, which had always been most friendly to the English; insomuch that in their hostile rage they spared not even the churches or monasteries. Those islanders , to the utmost of their power, repelled force with force, and imploring the assistance of the Divine mercy, prayed long and fervently for vengeance and though such as curse cannot possess the kingdom of God, it is believed, that those who were justly cursed on account of their impiety, did soon suffer the penalty of their guilt from the avenging hand of God; for the very next year, that same king, rashly leading his army to ravage the province of the Picts, much against the advice of his friends, and particularly of Cuthbert, of blessed memory, who had been lately ordained his op (preacher), the enemy made show as if they fled, and the king was drawn into the straits of inaccessible mountains, and slain with the greatest part of his forces, on the 20th of May, in the fortieth year of his age, and the fifteenth of his reign.

After the battle, King Bridei had the body of Ecgfrith interred in the monastery of Iona. Eight years later Bridei died and was himself buried on Iona. The Battle of Dun Nechtain was not decided by the will of God, but it did represent the consolidation of Pictish power in Northeast Scotland. These events also indicate the peaceful relations between the kingdoms of Dal Riata and Pictavia.

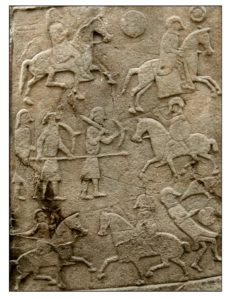

The Battle of Dun Nechtain is recorded on the Pictish sculpted stone in the Aberlemno Churchyard. In the upper part of the sculpture, a long-haired Pictish warrior advances from the left while an Anglo-Saxons with helmet and nose-guard flees to the right. In the middle three Pictish footsoldiers confront a mounted Anglo-Saxon. The bottom of the stone shows two mounted warriors fighting and on the right is shown the outcome with a raven pecking at the dead body of the Anglo-Saxon.

The final episode I shall consider was called Braflang Scóine or the “Treachery of Scone” (Clarkson, 2017, pp 178-194). According to stories recounted much later by such writers as Gerald of Wales writing in the late 12th Century, Kenneth MacAlpin (Cináed mac Ailpin), King of Dal Riata, invited the Pictish lords to a banquet at Scone. Unbeknownst to them their tables were set on boards placed over pits. At a signal from MacAlpin, the Scots

noted their opportunity and drew out the bolts which held up the boards; and the Picts fell into the hollows of the benches on which they were sitting, in a strange trap up to the knees so that they could never get up; and the Scots immediately slaughtered them all, tumbled together everywhere and taken suddenly and unexpectedly, and fearing nothing of the sort from allies and confederates, men bound to them by benefits and companions in their wars. (from Gerald of Wales De Instructiones Principis, translated in Clarkson, 2017, p 183).

Kenneth MacAlpin (810-858) then became King of the Picts and the first king of a united Scotland (Alba). The dates of his kingship are generally considered 843-858. The lurid details of the Treachery of Scone do not appear to represent any definite event (Hudson, 1991). The massacre is a myth, but it serves to explain the Scottish assimilation of the Picts. MacAlpin did indeed unify the Scottish peoples, and there is little historical mention of the Picts after about 900 CE.

The history of Scotland thenceforth involved battles with the Vikings to the North and with the English to the South, with Scotland continuing as an independent kingdom until the Act of Union of 1706 when Scotland became a part of Great Britain.

Pictish Symbols

The Picts left no written history. Their sculptured stones form their main surviving record. On many of these stones are incised or carved various symbols. Some of the symbols clearly represent animals or birds or fish. The others are mysterious.

Pictish stones have been classified by Allen and Anderson (1903) as: Class I, those with only symbols; Class II, those with Christian iconography (typically a cross) as well as symbols; and Class III those with Christian iconography and no symbols. Both Class II and Class III stones often portray people, in scenes of daily life, in battles, or in stories from the Bible. .

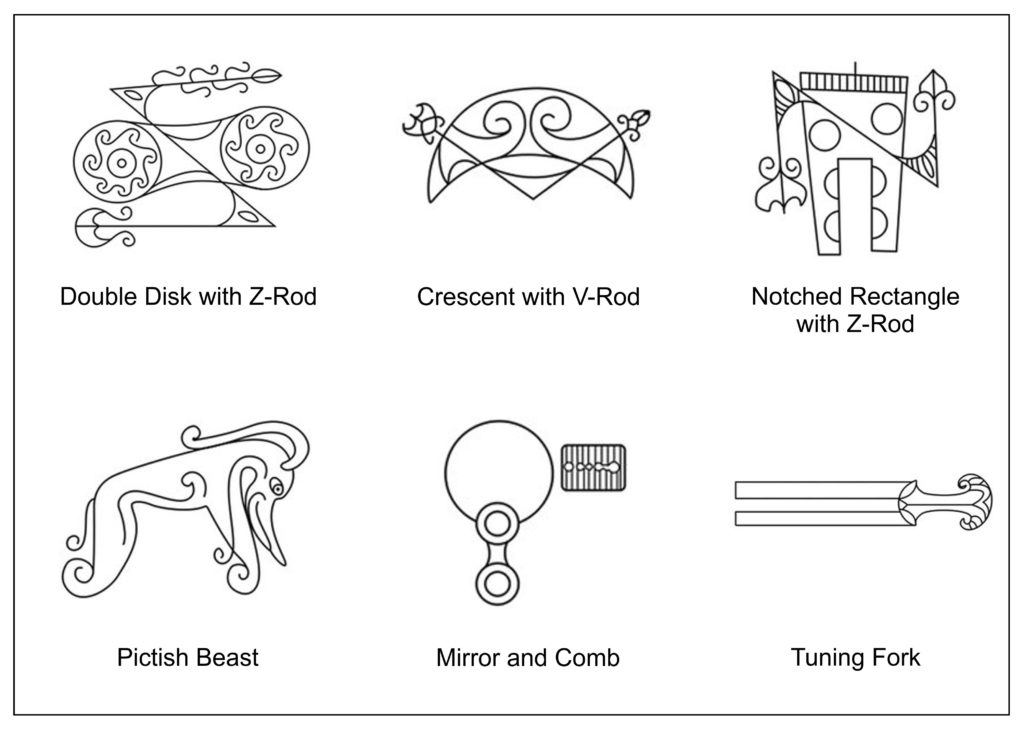

The following illustration shows six of the most common symbols found on Class I stones (Alcock, 1988, Forsyth, 1995; Jones, 2003; Fraser, 2008, McHardy, 2015; Noble et al., 2018):

No one knows what the symbols represent. Most interpreters relate the symbols to physical objects or animals; others suggest a more abstract or spiritual correlation. The double disk could indicate the sun and its transition from winter to summer. In more abstract terms, it could indicate a marriage, or the opposition of life and death. The crescent likely has some relation to the moon. The Z-rod and V-rod might represent broken spears or arrows. The notched rectangle might represent a chariot. The Pictish beast is clearly animate, but no one knows what animal it represents or whether the animal is real or imaginary. My own preference is for a dolphin. The tuning fork might represent the tongs used in metal work. This would fit with the Celtic expertise in working bronze. Others have suggested that it shows a broken sword.

Whether the symbols have further meaning is impossible to know. They might represent hieroglyphs like those in Egypt, or even a syllabic alphabet. As such they could have been used to name clans or families. The number of stones with symbols are far too few to allow easy linguistic analysis.

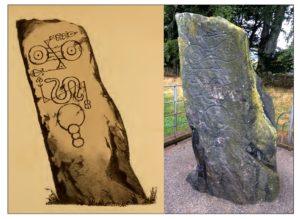

The stones might define territory or indicate a meeting place. They do not appear to commemorate persons since most stones are unrelated to burials. An exception is the Picardy Stone (Myreton Farm, near Insch), which was located above what appeared to be an empty grave. The stone is 2 meters high and has three incised symbols: a double disk with a superimposed Z-Rod, a serpent with a Z-Rod and a mirror. The illustration below compares a recent photograph (by Peter Richardson) with the engraving from Stuart (1856):

Class I Stones

Perhaps the most famous of the Class I stones is located beside the road in the village of Aberlemno. The stone is known as Aberlemno I or the Serpent Stone. The front side of the stone shows deeply incised Pictish symbols: a serpent above a double disk with a Z-rod, and a mirror and comb. On the lower part of the back of the stone are small cup marks, indicating that the stone was likely erected in Neolithic times and later carved by the Picts. The modern photograph from Wikipedia is compared to the engraving in Stuart (1856):

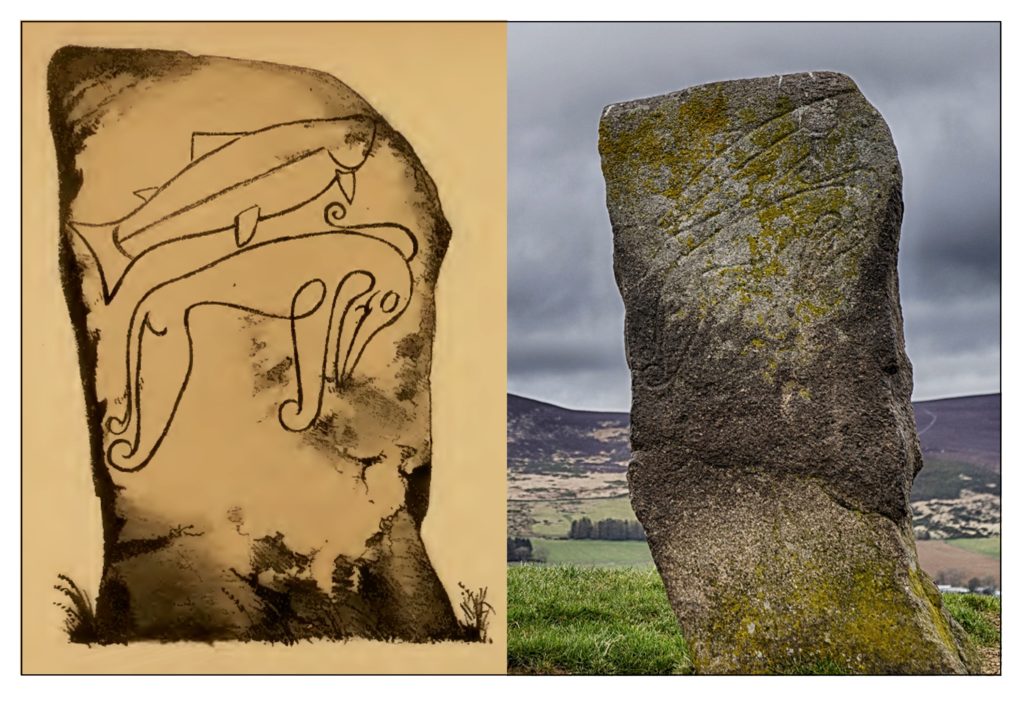

Another important Class I stone is the Craw Stane at Rhynie, which has outlines of a salmon and a Pictish beast. In the illustration a 2016 photograph by Allan Robertson is compared to Stuart’s 1856 engraving:

Class II Stones

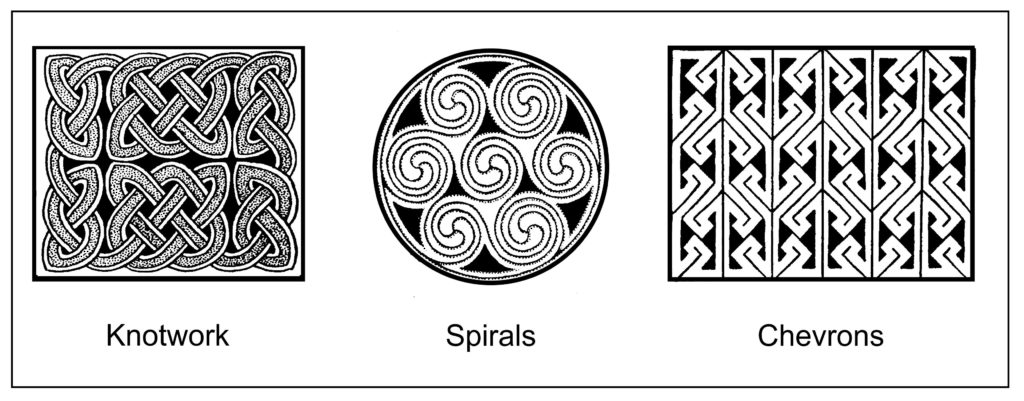

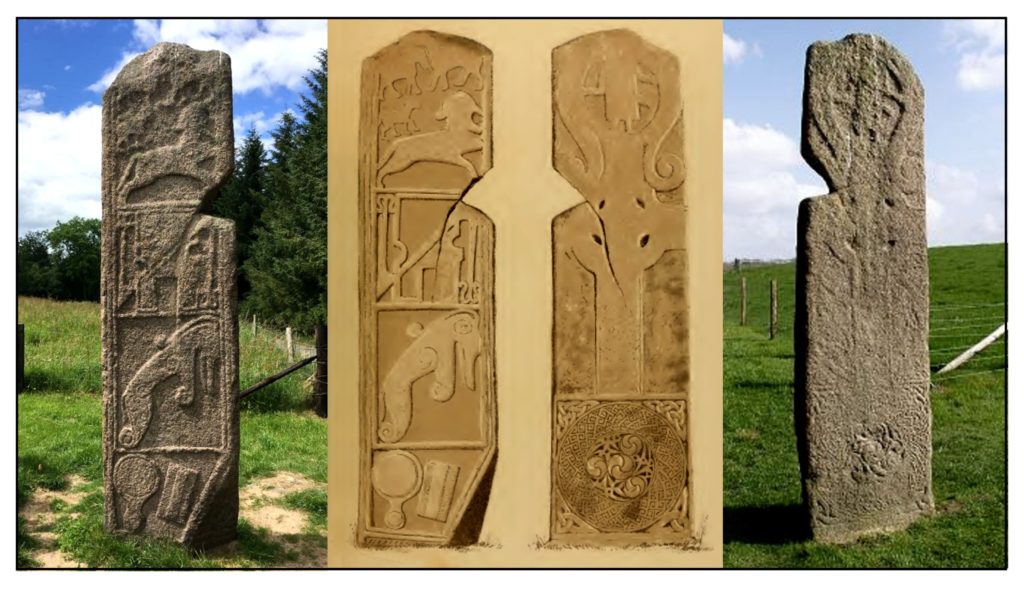

Class II stones differ from Class I stones in several ways. First, they are carved on stones that have been roughly squared and finished to form slabs. Second, the figures on these stones are carved in bas relief rather than incised. Third, the carvings are more representational than symbolic, often portraying people and animals. Fourth, they are ornamented with Celtic designs characteristic of Irish Art. Fifth, the stones include Christian iconography, typically a cross, but also scenes from the Bible or the lives of the Saints.

Celtic ornamentation was highly developed in Ireland (Laing & Laing, 1992, pp 138-196). The Class II Pictish stones were clearly carved under the influence of Gaelic artists. However, there was also interchange of ideas between the Celts (both Scots and Picts) and the Anglo-Saxons. Some of the major types of Celtic ornament are illustrated below with patterns from Bain (1973):

The Maiden Stone near Inverurie is one of the simplest of the Class II stones. One side shows a set of Pictish symbols: from top to bottom a centaur, a notched rectangle with a superimposed Z-rod, a Pictish beast, and a mirror and comb. The other side shows a human figure surrounded by two fish superimposed on a cross and a panel with Celtic spirals, now much eroded. The name of the Cross comes from a local legend about a maiden who was duped by the devil, but saved by being turned into stone. The notch on the slab is from the failed clutch of the Devil as he tried to capture the maiden.

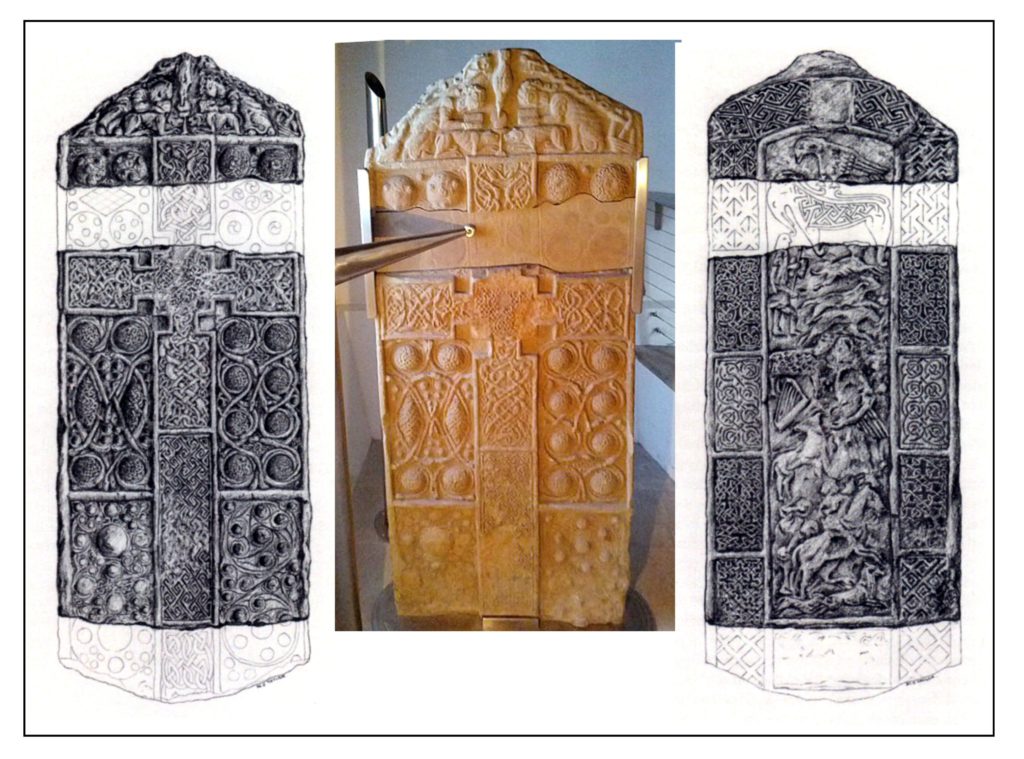

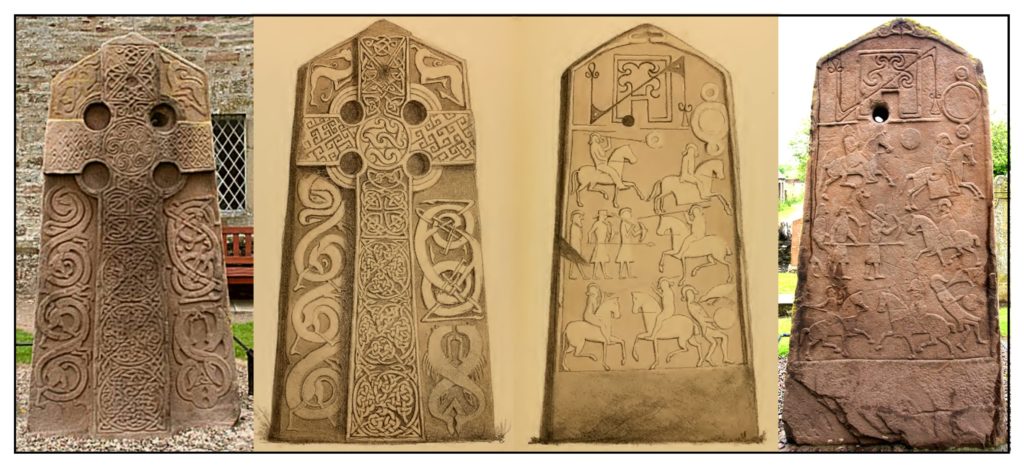

I have already considered the cross-slab in the Aberlemno Churchyard because of its representation of the Battle of Dan Nechtain. The cross side shows intricate Celtic ornamentation. The hole in the slab was drilled much later than the carving probably to help move the stone. The illustration compares modern photographs with the engravings from Stuart (1956):

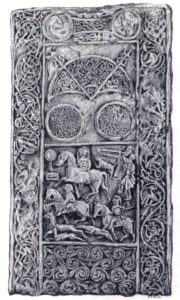

The Hilton Cadboll stone shows a beautifully carved hunting scene with a lady riding side-saddle. The cross side of the stone was erased and inscribed with a 17th century memorial. The stone was transferred to the National Museum of Scotland, and a replica by Barry Groves was erected at the original site. The illustration at the right shows a drawing by Mike Taylor (MacNamara, 1999) and below is a photograph by Stephanie McGucken of the replica.

The Nigg Stone is perhaps the most intricately decorated of all the Pictish stones. The cross side of the stone shows beautifully carved patterns of many kinds. Above the cross is a scene that is said to represent St Paul and St Andrew, each with a lion at their side, being brought a loaf of bread by a raven – food for their meditation. On the other side of the stone intricate Celtic designs surround a central hunting scene. Because of the harp, one of the figures may represent David. However the harp is as much a Celtic symbol as a Christian one. At the top of this side are the symbols of a bird and a Pictish beast. The stone was broken long ago and has recently been put back together. The illustration shows a photograph of the reconstruction and drawings by Mike Taylor (MacNamara, 1999).

Class III Stones

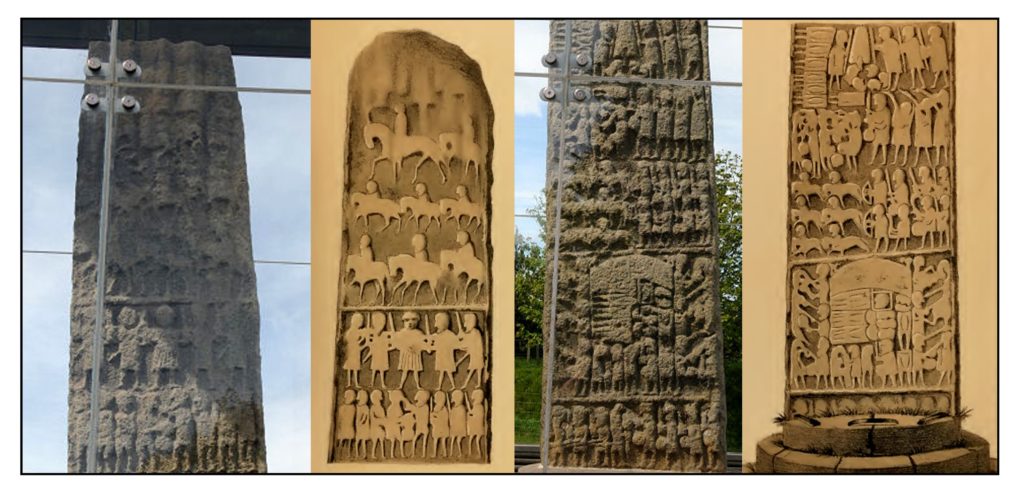

With a height of 7 meters, Sueno’s Stone in Moray is the tallest of the Pictish stones. The name refers to the Sweyn, a Danish king who conquered Britain and became its king in1013 CE. However, there is no evidence for any association between Sweyn and the stone, which was likely erected over a century before his exploits. One side of the stone depicts a cross and other carvings that have been almost completely eroded. The better preserved side shows an amazing sequence of scenes that narrate a battle.

The uppermost panel portrays mounted warriors arriving at the battle from the right. The second panel shows the fighting between foot-soldiers, with some of the warriors on the left side turning as if to flee. The upper line of the third panel shows the army of the right besieging a palisade. In the left middle of this panel is a pile of beheaded corpses. On the right the victorious soldiers appear to be blowing the bronze trumpets (carnyces) used by the Celts in battle. The fourth panel shows more corpses underneath what might be a bridge. The bottom strip of the stone seems to show prisoners tied up. No one is sure what battle is represented. Perhaps the Picts were fighting the Vikings; more likely they were fighting amongst themselves. The stone is now protected from the elements in a cage of armoured glass. The photographs in the following illustration are from the Undiscovered Scotland website and the engravings are from Stuart (1856):

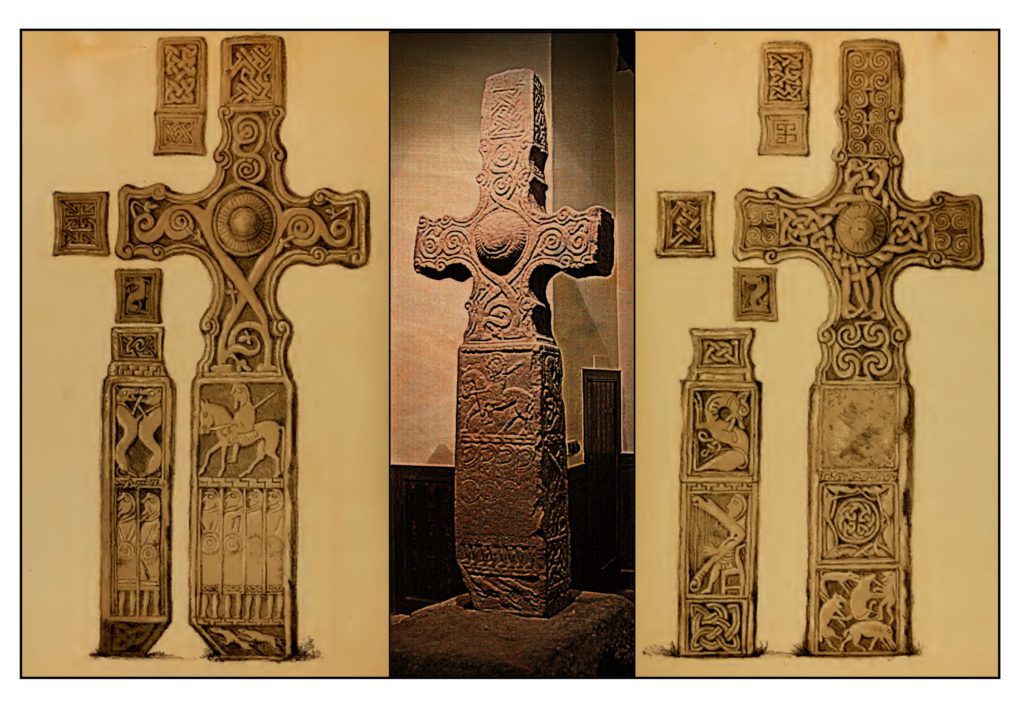

The Dupplin Cross differs from almost all of the other Pictish stones. The cross is not a slab upon which a cross has been carved, but a completely free-standing cross. Originally located on an open hillside it is now preserved in St Serf’s Church in Dunning. The cross is beautifully carved with Celtic patterns and a variety of scenes with no apparent narrative relationship. The most striking carvings are the Pictish rider on the front and David playing his harp on the right side. The engravings are from Stuart (1856) and the photograph (2014) by Colin Gould:

Legacy of the Picts

The Picts maintained their fierce independence for centuries, defending their territory from Romans, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings. They occur briefly in the records of those who fought with them, but they left no history of their own. They were a people as mysterious as the symbols they left on stones. Toward the end of the first millennium they became assimilated with the other peoples in the melting pot of Scotland. Their stones remain as an integral part of the Scottish landscape (photo Cathy MacIver):

References

Adamnan, Abbot of Hy (7th Century CE, Edited by W. Reeves, 1874). Life of Saint Columba, Founder of Hy. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. Available at CELT

Alcock, E. A. (1988). Pictish stones class I: Where and how? Scottish Archaeological Journal, 15, 1-21

Allen, J. R. & Anderson, J. (1903). The early Christian monuments of Scotland. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (Neill & Co.) Available at Archive.org: Part I and 2, Part 3.

Bain, G. (1973). Celtic art: The methods of construction. New York: Dover Publications.

Bede (8th Century, translation 1910). The Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Available at Fordham University or Christian Classics Ethereal Library.

Clarkson, T. J. (2008, revised 2017). The Picts: A history. Edinburgh: Berlinn (John Donald).

Clarke, D. L. (1966). A tentative reclassification of British beaker pottery in the light of recent research. Palaeohistoria, 12, 179-198.

Cunliffe, B. W. (2018). The ancient Celts. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Forsyth, K. (1995). Some thoughts on Pictish symbols as a formal writing system. In Henderson, I. and Henry, D. (Eds) The worm, the germ and the thorn: Pictish and related studies presented to Isabel Henderson (pp. 85-98). Brechin, Angus: Pinkfoot Press

Fraser, I. (2008). The Pictish symbol stones of Scotland. Edinburgh: Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland.

Harding, D. W. (2007). The archaeology of Celtic art. London: Routledge.

Henderson, G., & Henderson, I. (2004). Art of the Picts: Sculpture and metalwork in early medieval Scotland. New York, N.Y: Thames & Hudson.

Hudson, B. T. (1991). The conquest of the Picts in early Scottish literature. Scotia, 15, 13-25.

Hudson, B. T. (2014). The Picts. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, D. (2003). A wee guide to the Picts. Musselburgh, Scotland: Goblinshead.

Laing, L. R., & Laing, J. (1992). Art of the Celts. London: Thames and Hudson.

MacNamara, E., (1999). The Pictish stones of Easter Ross (with illustrations by M. Taylor). Tain, Ross-shire: Tain and District Museum Trust.

Manco, J. (2015). Blood of the Celts: The new ancestral story. London: Thames and Hudson.

McHardy, S. (2015). Pagan symbols of the Picts. Edinburgh: Luath Press.

Noble, G., Goldberg, M., & Hamilton, D. (2018). The development of the Pictish symbol system: Inscribing identity beyond the edges of Empire. Antiquity, 92, 1329-1348

Olalde, I., Brace, S., Allentoft, M.E., Armit, I.A., et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe. Nature, 555, 190-198.

Pearson, M. P., Chamberlain, A., Jay, M., Richards, M. et al. (2016). Beaker people in Britain: migration, mobility and diet. Antiquity, 90, 620-637.

Salanova, L., Prieto‐Martínez, M. P., Clop‐García, X., Convertini, F., Lantes‐Suárez, O., &Martínez‐Cortizas, A. (2016). What are large‐scale Archaeometric programmes for? Bell beaker pottery and societies from the third millennium BC in Western Europe. Archaeometry, 58, 722-735.

Stuart, J. (1856, 1867). Sculptured Stones of Scotland. Aberdeen: Spalding Club. Available at Archive.org: Volume I and Volume II.

Tacitus (circe 98 CE, translated by William Peterson, 1914). Dialogus, Agricola, Germania. London: Heinemann. Available at Archive.org

Woolf, A. (1998). Pictish matriliny reconsidered. The Innes Review, 49 147-167

Thank you Terry for a fascinating story of an unknown and mysterious nation. At the same period that the Romans fought the Pictish nation, they also fought my ancestors and eventually exiled them from their country. In one of those wars, which took place in Yodphat in the Galilee, which I see every day from my living room, the besieged Jews were about to lose the battle and decided to commit a mass suicide, rather than become slaves to the Romans (much like the case of Massada). The last person alive, before killing himself decided that if he died, no one would know about the revolt and the people that carried it out. So, rather than kill himself, he surrendered to the Romans and made it his mission to write about the history of the Jews and the wars of the Jews (two voluminous and detailed accounts that survived until today and were translated to many languages, including English). His name was Josephus Plavius and thanks to his writings we know about that fateful period. His books have guided present day archeologists and the digs confirmed his accounts, including measurements of buildings he described and were eventually unearthed). He has been a controversial figure in his time, and in critical historical writings about the period. Your study of the Pictish nation provides the perfect control case of what might have happened if he did not betray his cause: a nation lost in history because there were no records of its history. It is a philosophical dilemma that remains undecided – what is nobler – to die for your principles or to spread them for perpetuity by temporarily betraying them.

Hi Hillel. You make a fascinating comparison between what happened in the East and West of the Roman Empire in the first centuries of the common era. I agree that the recording of history is of the utmost importance. One should not be too seduced by the rhetoric of Calgacus.

The website of Historic Environment Scotland has extensive information about many Scottish historical sites, including most of the stones discussed in this blog:

https://www.historicenvironment.scot/archives-and-research/publications/?publication_type=45