Death is inevitable. What it entails is largely unknown. Some believe that it permanently ends an individual’s existence; others that it simply provides a transition to another form of life. Most people fear it, but some consider it with equanimity. Among the latter are the followers of Epicurus, who claimed

Death is nothing to us. For what has been dissolved has no sense-experience, and what has no sense-experience is nothing to us.

(Epicurus, reported by Diogenes Laertius, translated by Inwood and Gerson, 1997, p 32; another translation is by Yonge, 1983, p. 474).

Epicurus proposed that human beings are made of complex compounds of atoms. At death these compounds dissolve, releasing the atoms to form other things. The body decays and the soul evaporates. Once we are dead, we are no more. We cannot feel what it is like to be dead. And the dead certainly cannot experience pain. Death should therefore not be feared.

Epicureanism was popular during the Roman period. A common Latin epitaph summarized the life of the Epicurean as a brief interlude between the nothingness preceding birth and the nothingness following death:

Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo

(I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care).

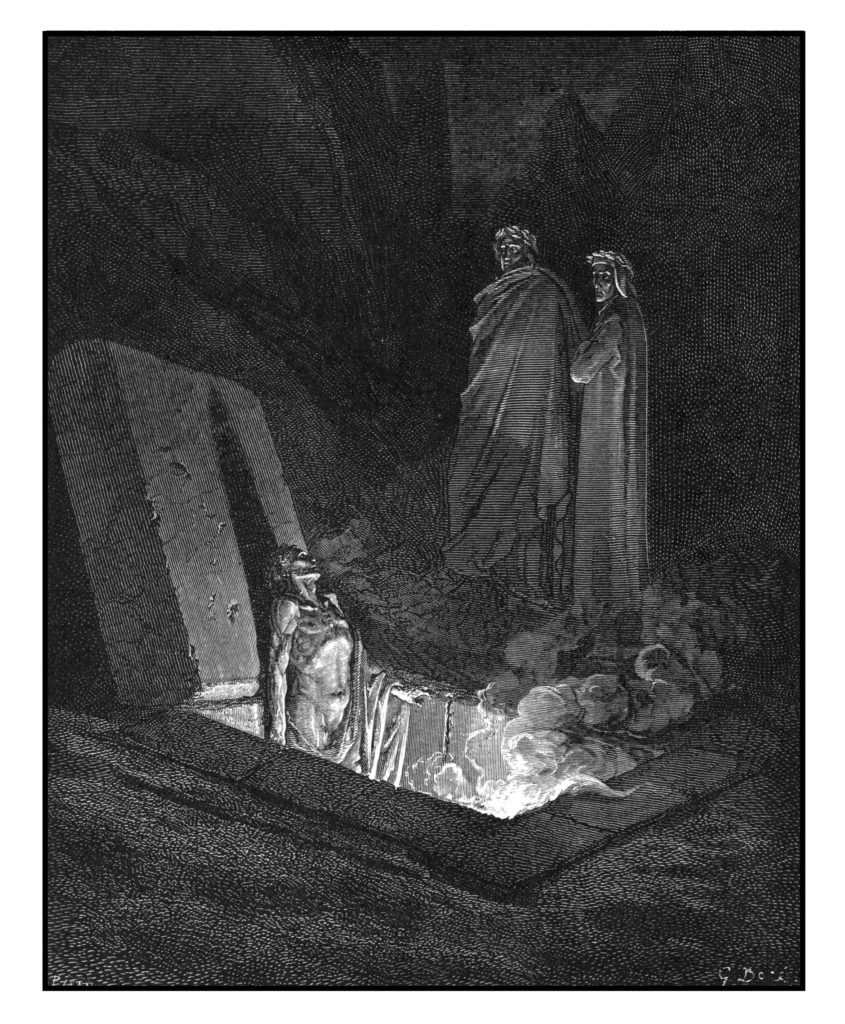

As Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, Epicureanism faded into obscurity. Dante placed the Epicureans in the Sixth Circle of his Inferno (1320, Canto X). Those who did not believe in the afterlife were forced to spend eternity in graves that were completely closed just as in life their tenants’ obstinacy kept them from the truth. The graves were filled with fired graves just as in life the Epicureans were consumed by their heresy.

As the Western world moved away from the dogmatism of the Middle Ages, the idea that man was not immortal was once again considered. Those who now reject any belief in an afterlife sometimes adopt the bravado of the Epicurean epitaph. But more often than not they care deeply about death as the defining event in a life. It is not nothing.

Atoms and the Void

The philosophy of Epicurus derives from the atomism of Democritus (460-370 BCE). Democritus was born and lived in Abdera, a city in Northern Greece, at about the same time as Socrates was active in Athens. Democritus maintained that everything was made of tiny indestructible atoms (Berryman, 2016). He claimed to have learned this from Leucippus, about whom little is known, and who may be more mythical than real.

Democritus was called the “laughing philosopher” to distinguish him from Heraclitus (535-475 BCE), the “crying philosopher,” who believed that nothing was indestructible and that everything is forever changing. The cheerful and the tearful.

Of the many writings of Democritus, we now have only fragments, the most famous of which is

By convention sweet is sweet, bitter is bitter, hot is hot, cold is cold, color is color; but in truth there are only atoms and the void (translation by Will Durant, 1939, p 393).

The concepts of the atom and the void were derived from a combination of observation and logic. Everyone perceives that the world contains objects and that these objects move: matter and motion. Objects can be broken down into smaller pieces, and these pieces can themselves be broken down into even tinier particles. But this breaking down can only proceed so far, or all objects would by now have been broken down to nothing. There must therefore be some indivisible particle beyond which matter cannot be further broken. These atoms (from the Greek atomos, uncuttable) are so tiny that they are cannot be seen by the eye: invisible and indivisible. The void is necessary to explain how things move. How could something change its location unless there were empty space for it to move into?

Atoms are infinite in number but of a finite number of types. Moving atoms collide with one another and join to form compounds. These compounds interact with each other to create all that exists in the world. Combining atoms is like forming words with the letters of the alphabet. From a few letters come a myriad words.

Though atoms are eternal, the compounds that they form are transient. Rock erodes to sand, which under pressure becomes stone again. Water evaporates and then condenses. Living things develop, become mature and then die. At death, the components of the body break apart, releasing its atoms for making other compounds.

Imperious Caesar, dead and turn’d to clay,

Might stop a hole to keep the wind away (Hamlet, V:1)

The soul is composed of atoms just like everything else. The atoms of the soul are extremely fine, perhaps similar to the atoms of fire. They permeate the body, giving it a conscious spirit. When the body dies, the atoms of the soul dissolve back into the void like all the other atoms of the body. The soul does not persist beyond death. There is no afterlife. We are transient like everything else, mortal like all other living things.

Democritus’ absolute materialism differed from the philosophy of Plato, who proposed the primacy of ideas. Indeed, Plato was so upset with his rival’s teachings that he reportedly urged that all the books of Democritus should be burned (Diogenes Laertius, p 393). So much for freedom of thought in a republic governed by philosophers.

The Garden of Epicurus

The ideas of Democritus were extended by Epicurus (341-270 BCE), who was born on the Greek island of Samos off the west coast of Turkey. In 306 BCE Epicurus established a school of philosophy in Athens that met in a garden below the Acropolis (Jones, 1989; Konstan, 2018; O’Keefe, 2010; Wilson, 2015).

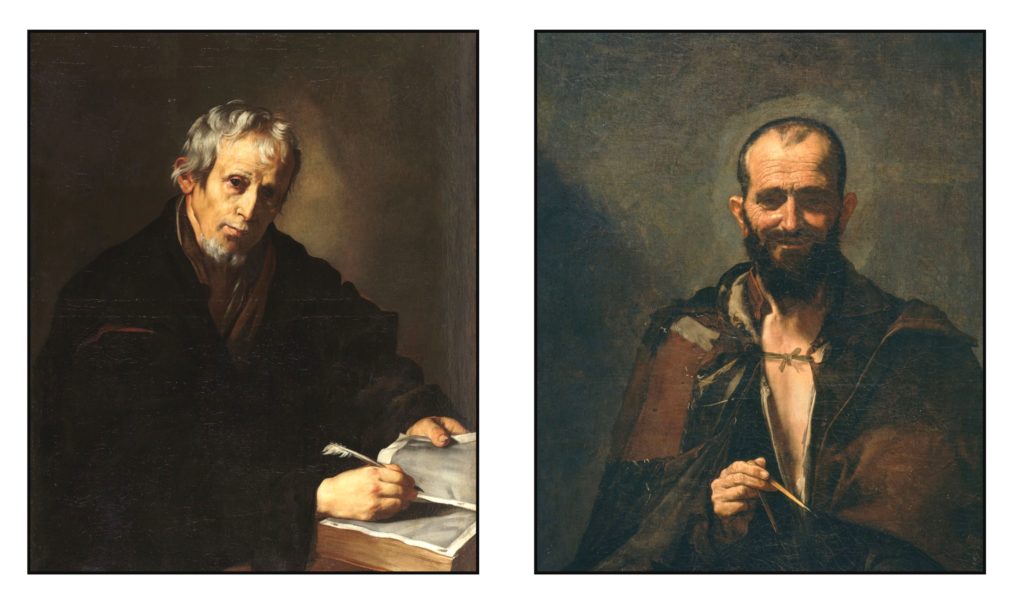

He wrote extensively though none of his books survived the anti-heretical campaigns of the Christian Church. Most of what we know about Epicurus is preserved in the biography written by Diogenes Laertius (3rd Century CE), which includes some of the letters written by the philosopher to his colleagues, and a listing of his Principle Doctrines (Kyriai Doxai). The philosophy of Epicurus was popular in the Roman Empire, and several statues of Epicurus have survived in Roman copies (see right).

Among the lost books of Epicurus was the Kanon (Rule, Criterion) which discussed how true knowledge could be obtained. Epicurus proposed that sensation is the most dependable criterion of truth – the world is what we perceive. Ideas derive from rather than precede the analysis of sensory information. This seems to have differed from the ideas of Democritus, who believed that our perceptions were as much convention as reality.

In the lost Peri Physis (On Nature) Epicurus presented and extended the atomism of Democritus. He acknowledged that there are only atoms and the void. The body and the soul are made of atoms that fall apart when the corporeal body dies and the conscious soul ceases. We do not live forever.

Epicurus appears to have deviated from the fixed determinism of Democritus byproposing the idea of the clinamen (swerve). Atoms falling through the void would never collide to form compounds unless some atoms at some time swerved from their predetermined path. Democritus also suggested that this unpredictable random movement was the basis of our free will, when we act according to what is desired of the future rather than what has been ordained by the past. In recent years similar ideas based on the uncertain behavior of atoms in the brain have been used to explain free will. Unfortunately, these ideas have little explanatory value. My actions are no more free when determined by random events in the present than when determined by the fixed events of the past.

Free will was important to Epicurus because he wished us to choose the good life. This depended on maximizing our happiness. Although maligned by Christian polemicists as a decadent libertine, Epicurus actually practiced an ascetic hedonism. He valued most the simple sensory pleasures of his garden and the friendship of his colleagues. He eschewed any participation in politics as causing too much anxiety. His goal was ataraxia (tranquility, peace of mind, from a- not and tarasso, disturb).

Although he was described as an atheist, Epicurus thought that the gods were real because our ideas of them were just too clear to be ignored. However, he argued that the gods were not in any way concerned with human affairs. Like true Epicurean, the gods enjoy themselves and refuse to be bothered by human politics.

Epicurus proposed that we should not be frightened of death. Since our consciousness ceases when we die, death is not painful. Since the gods are not concerned with human beings, they have not provided an afterlife of punishment for all that we have done wrong. If we attain a life of ataraxia, it matters not how long we live (Lesses, 2002; Mitsis, 2002). Death is the natural and inevitable end to life. The following is from the Letter to Monoeceus:

Get used to believing that death is nothing to us. For all good and bad consists in sense-experience, and death is the privation of sense-experience. Hence, a correct knowledge of the fact that death is nothing to us makes the mortality of life a matter for contentment, not by adding a limitless time to life but by removing the longing for immortality. For there is nothing fearful in life for one who has grasped that there is nothing fearful in the absence of life. Thus, he is a fool who says that he fears death not because it will be painful when present but because it is painful when it is still to come. For that which while present causes no distress causes unnecessary pain when merely anticipated. So death, the most frightening of bad things, is nothing to us; since when we exist, death is not yet present, and when death is present, then we do not exist. (Inwood & Gerson, 1997, p 29)

Epicurus practiced what he preached. He died from an attack of kidney stones. Despite severe and prolonged pain, he maintained his ataraxia. His cheerfulness of mind and his memory of philosophy counterbalanced his afflictions.

De Rerum Natura

In about 50 BCE Titus Lucretius Carus published a long Latin poem about the Nature of Things. The poem probably derives from the Peri Physis of Epicurus. Little is known about the poet. In his Chronicon (circa 380 CE), written some 400 years later, Saint Jerome included an entry for the year 94 BCE:

Titus Lucretius, poet, is born. After a love-philtre had turned him mad, and he had written, in the intervals of his insanity, several books which Cicero revised, he killed himself by his own hand in the forty-fourth year of his age. (translation by Santayana, 1910, p 19)

Saint Jerome was a devout Christian, completely opposed to the beliefs of Epicurus, who claimed that the gods had nothing to do with human life, and who denied the immortality of the soul. Most critics feel that Jerome was simply trying to belittle the poet and to cast his work as nonsense: be not seduced by Epicureanism, since madness and suicide follow from such heresies (e.g., Sedley, 2018, and Smith, 1992 in his introduction to the Loeb edition of De Rerum Natura). However, the biography may contain some threads of truth:

The love-philtre in this report sounds apocryphal; and the story of the madness and suicide attributes too edifying an end to an atheist and Epicurean not to be suspected. If anything lends colour to the story it is a certain consonance which we may feel between its tragic incidents and the genius of the poet as revealed in his work, where we find a strange scorn of love, a strange vehemence, and a high melancholy. It is by no means incredible that the author of such a poem should have been at some time the slave of a pathological passion, that his vehemence and inspiration should have passed into mania, and that he should have taken his own life. (Santayana, 1910, pp 19-20).

De Rerum Natura is like no other poem: a scientific treatise expressed in verse. The poetry is characterized by brilliant language and intense imagery. Most impressive is the ongoing energy of the argument as Lucretius moves from atoms to death, from the soul to the cosmos, from the weather to the plague.

The poem begins with a beautiful invocation of Venus as the mother of Aeneas, founder of Rome, as the patron of all the creative forces in the world, and as the personification of Epicurean pleasure:

Life-stirring Venus, Mother of Aeneas and of Rome,

Pleasure of men and gods, you make all things beneath the dome

Of sliding constellations teem, you throng the fruited earth

And the ship-freighted sea — for every species comes to birth

Conceived through you, and rises forth and gazes on the light.

The winds flee from you, Goddess, your arrival puts to flight

The clouds of heaven. For you, the crafty earth contrives sweet flowers,

For you, the oceans laugh, the skies grow peaceful after showers,

Awash with light. (I: 1-10 Stalling translation)

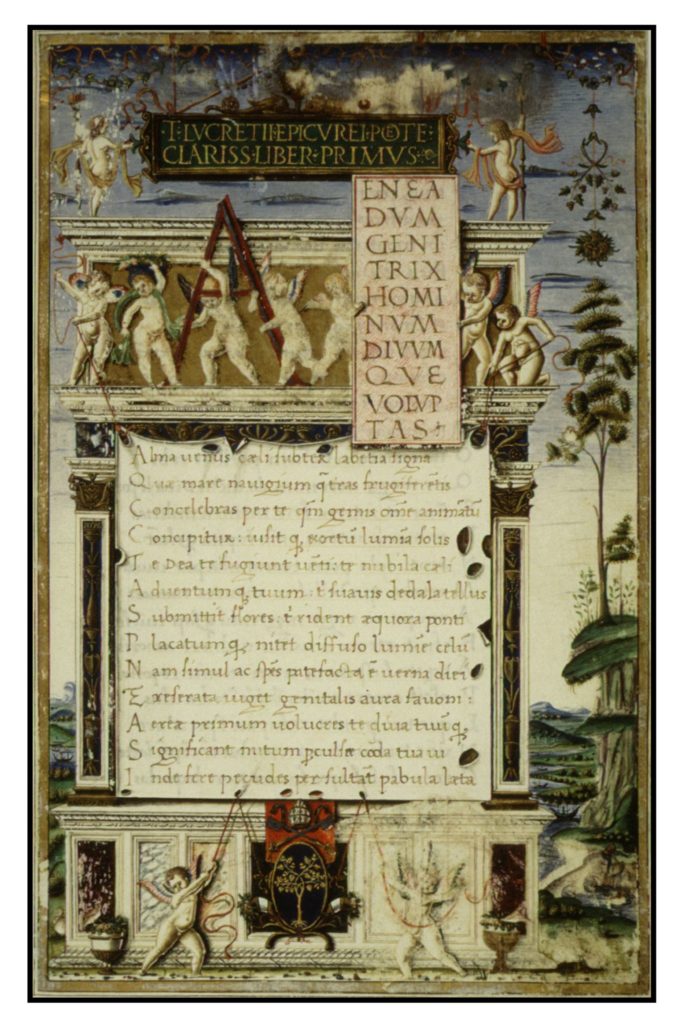

On the right is the first page of a 1483 manuscript copy of the poem made for Pope Sixtus IV by Girolamo di Matteo de Tauris. The Latin text begins

Aeneadum genetrix, hominum divomque voluptas,

Alma Venus, caeli subter labentia signa

Quae mare navigerum, quae terras frugiferentis

The beginning of the poem immediately questions the Epicurean view that the gods are not involved with the human world. Why should Lucretius invoke Venus as a partner in his poetry? The gods are a problem for Epicureanism: if they are real, they must be made of atoms and, if so, they cannot be immortal; yet, if they are mortal, they are not gods. Lucretius probably considered the gods more as metaphors than as real beings. Later in the poem (II: 646-660) he remarks that it is customary to call the sea Neptune, the corn Ceres and the wine Bacchus without actually meaning that these things are divine.

Lucretius quickly indicates that superstitious belief in the gods can lead to terrible wrongs by recounting the story of Iphigenia, daughter of Agamemnon, who was sacrificed at Aulis to propitiate the anger of the goddess Artemis, and obtain fair winds to send the Greek ships to Troy. The illustration at the left shows a fresco in the House of Tragic Poet in Pompeii from about the same time as Lucretius. Iphigenia is carried by Achilles and Ulysses to be sacrificed by Calchas the priest, while her father on the left refuses to observe her death. Above, the goddess Artemis arranges for a stag to be substituted for Iphigenia, who will be spirited away. However, this will be done without any of the Greeks realizing that Iphigenia was not actually sacrificed. Human sacrifice is also part of the Hebrew Bible, which recounts the attempted sacrifice of Isaac in Genesis 22 and the actual sacrifice of Jephthah’s daughter in Judges 11. As Lucretius clearly states, Iphigenia was

An innocent girl betrayed to a sort of incest

To be struck down by the piety of her father

Who hoped in that way to get a good start for his fleet.

That is the sort of horror religion produces.

(I: 98-101, Sisson translation).

De Rerum Natura recounts the principles of atomism espoused by Epicurus. Lucretius describes the clinamen or swerve, and notes its importance for free will. We are not completely determined by our past:

Again, if all motion is always one long chain, and new motion arises out of the old in order in-variable, and if the first-beginnings do not make by swerving a beginning of motion such as to break the decrees of fate, that cause may not follow cause from infinity, whence comes this free will in living creatures all over the earth, whence I say is this will wrested from the fates by which we proceed whither pleasure leads each, swerving also our motions not at fixed times and fixed places, but just where our mind has taken us? (II: 252-260, Rouse translation).

Lucretius considers death in many ways. The following passage provides the principal Epicurean argument:

So death is nothing, and matters nothing to us

Once it is clear that the mind is mortal stuff.

…

So when we are dead and when our body and soul

Which together make us one, have come apart,

Nothing can happen to us, we shall not be there,

Nothing whatever will have the power to move us,

Not even if earth and sea got mixed into one.

(III: 830-1, 838-842, Sisson translation)

Lucretius also adds the analogy of the mirror to the Epicurean comparison of the time before birth to the time after death. If we are not concerned with what occurred before we are born, why should we be afraid of its mirror-image: the time after we have died and once again do not exist:

Now look back: all the time that ever existed

Before we were born, was nothing at all to us.

It is a mirror which nature holds up for us

To show us what it will be like after our death.

Is it very horrible? Is there anything sad in it?

Is it any different from sleep? It is more untroubled.

(III: 972-977, Sisson translation)

The poem goes on to consider many natural phenomena. Some of the explanations that Lucretius offers are good, and some are similar to those proposed in modern science. However, most of the explanations are wrong. Science and poetry are not well suited: poetry attempts to say things that will last forever, whereas science is always changing.

At the end of the VI Book of De Rerum Natura Lucretius vividly describes the great Plague of Athens that began in 430 BCE during the Peloponnesian War. There is great debate about the nature of the plague, which was perhaps caused by an Ebola-like hemorrhagic fever.

The symptom first to strike was fiery fever in the head,

And both eyes, burning hectic bright, were all shot through with red.

The throat as well would sweat with blood, all black within. And stung

With sores, the pathway of the voice would clog and choke. The tongue,

Interpreter of the mind, oozed pus, and, made limp with the smart,

Was too heavy to move, and rough. Thence the disease would start,

Passing the gullet, to fill the chest, and flood the heavy heart

Of the afflicted, and then, indeed, all of the gates of Life

Began to give. From the open mouth, there would exhale a rife

Stink, like the stench of rank unburied corpses left to rot.

And then all of the powers of the mind and body, brought

To the very brink of doom, began to flicker. Mental strain

Ever danced attendance on intolerable pain;

Pleas mingled with moans. Ceaseless retching, lasting day

And night, was ever causing seizure and cramp, and wasting away

The strength of men already racked with suffering and worn out.

(VI: 1145-1161, Stallings translation)

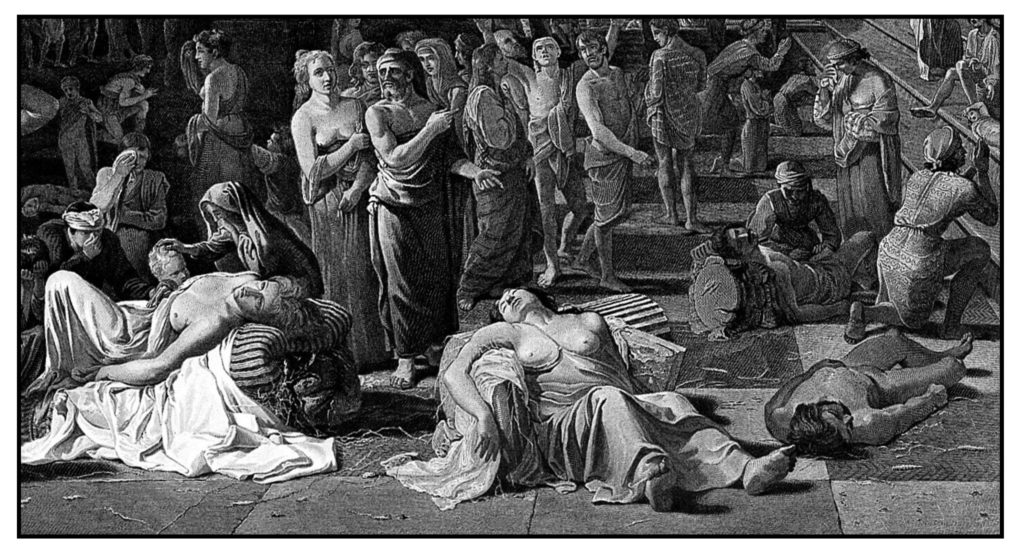

Death was everywhere. Below is a detail of an engraving (from the Wellcome Library) from a 1654 painting by Michael Sweerts, once thought to represent the plague of Athens:

The prevalence of death tore at the moral fabric of the city:

The present grief was overwhelming. No one any more

Observed the rites of burial they had observed before,

For the whole populace was thrown in disarray and cowed.

Each mourner buried his dead just as the time and means allowed.

Squalid Poverty and Sudden Disaster would conspire

To drive men on to desperate deeds — so they’d place on a pyre

Constructed by another their own loved-ones, and set fire

To it with wails and lamentation. And often they would shed

Much blood in the struggle rather than desert their dead.

(VI: 1278-1286, Stallings translation)

De Rerum Natura ends here. Most critics feel that Lucretius died before he could finish his poem, and that he probably intended to explain how philosophy could help one face the horrors of such a plague with equanimity. But he did not. And one wonders if he could not.

Stoicism

At the time of Epicurus, Athens was home to several other schools of philosophy. The most important of these were the Skeptics who refused to believe in anything, and the Stoics who differed from the Epicureans mainly in their promotions of virtue rather than pleasure as the goal of human life (Baltzly, 2019; Long, 1986). The Stoics proposed that the universe proceeded according to its own Logos, and that human benefit was not necessarily part of this determined path. One had to accept one’s fate and do the best that one could. The Stoical idea of the Logos goes back to Heraclitus. Indeed, Stoics and Epicureans can trace their emotional origins to tearful Heraclitus and cheerful Democritus.

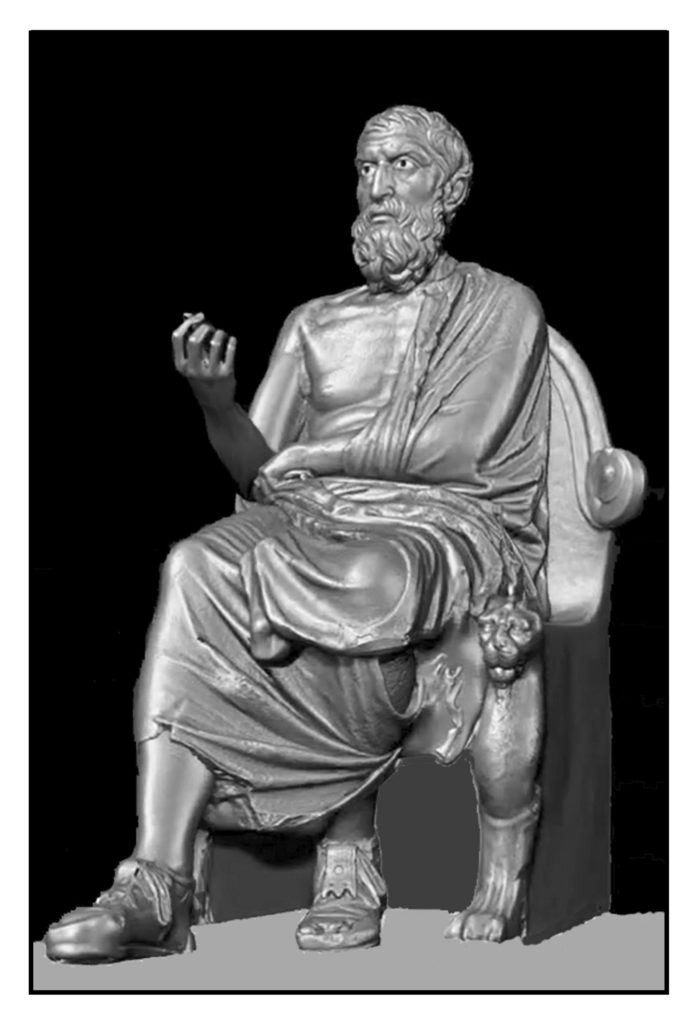

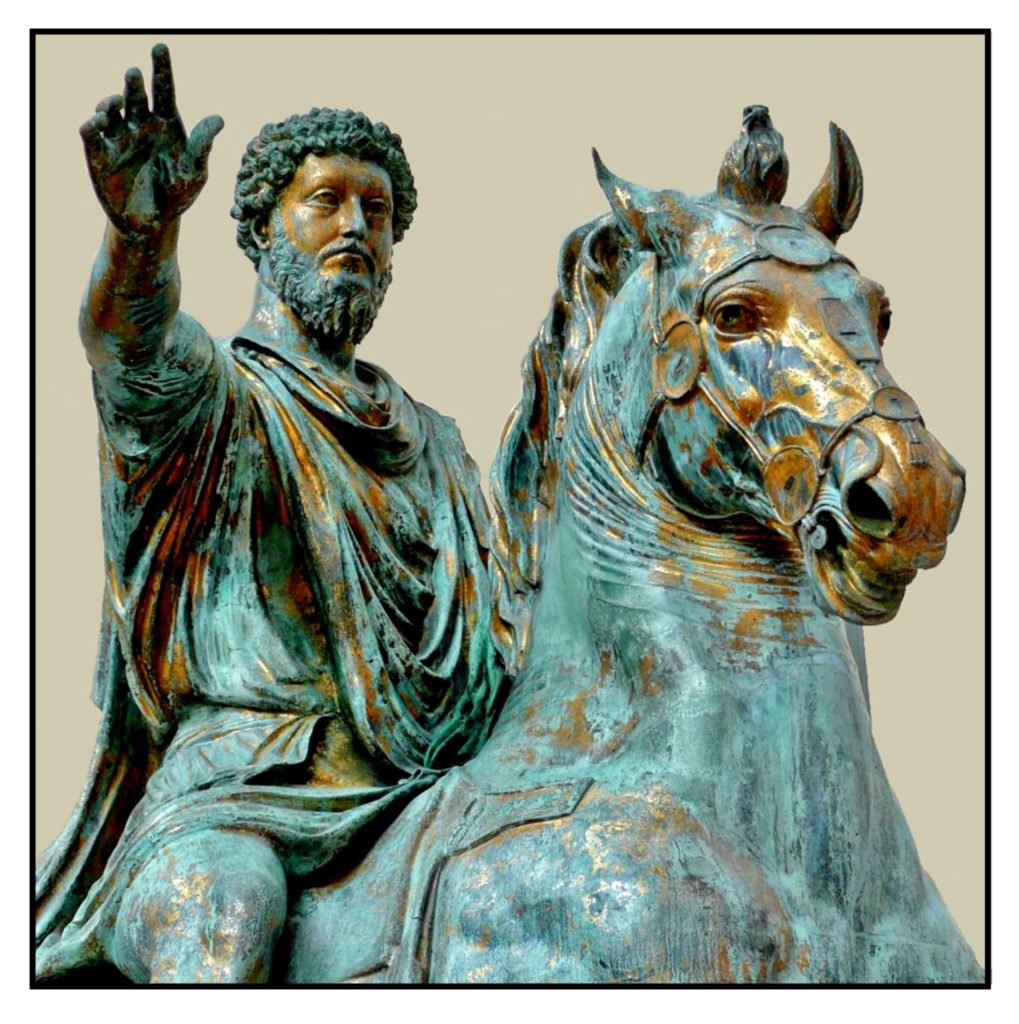

The Stoics also differed from the Epicureans in their approach to death. While the Epicureans tried to ignore death, the Stoics paid it constant attention. Death brings one’s life to an end, and therefore settles the sum of one’s virtues and achievements. Life should therefore be lived as if death were imminent. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius, the 175 CE statue of whom is illustrated on the left, voiced these Stoical precepts in his Meditations:

Every moment think steadily as a Roman and a man, to do what thou hast in hand with perfect and simple dignity, and feeling of affection, and freedom, and justice; and to give thy self relief from all other thoughts. And thou wilt give thyself relief, if thou doest every act of thy life as if it were the last, laying aside all carelessness and passionate aversion from the commands of reason, and all hypocrisy, and self-love, and discontent with the portion which has been given to thee.

Do not act as if thou wert going to live ten thousand years Death hangs over thee. While thou livest, while it is in thy power, be good

(Marcus Aurelius, 180 CE, II: 5 and III: 17, translation by Long)

Stoicism became more popular with the Romans than Epicureanism. And Stoicism fitted more easily to the doctrines of Christianity, which accepted and transformed the Stoic idea of Logos, making Christ its personification.

Epicurus and Modernity

The works of Democritus and Epicurus did not survive beyond Roman times. However, a manuscript of De Rerum Natura by Lucretius was diligently copied and re-copied by Christian monks, and finally discovered in a German monastery in 1417 by Poggio Bracciolini (Greenblatt, 2011). The first printed publication of De Rerum Natura was in 1473.

The rediscovered book brought the atomism of Democritus and Epicurus to the attention of the philosophers and scientists of Europe. Pierre Gassendi (1592-1665) in France and Robert Boyle (1627-1691) in England were attracted to the explanatory power of atoms and developed a “corpuscular philosophy” (Wilson, 2008). They tried but failed to reconcile this atomism with Christian beliefs in the immortal soul and a beneficent God.

As science progressed, corpuscular philosophy developed into modern chemistry. Atoms of different types combine to form molecules of various chemical compounds. The pressure of a gas depends on the force exerted by the continual movement of its molecules. This is illustrated on the right, in which five of the molecules are colored red to make their motion easier to follow. The molecules move like the motes of dust in the sunlight that were described in De Rerum Natura (Book II:62-79). Science now knows that atoms are not indivisible, but modern science owes much to Lucretius.

As the Enlightenment progressed, some thinkers decided to reject God and immortality and to accept Epicurus’ views of death. Of these perhaps the most famous is David Hume (1711-1776) who, when dying of cancer, was interviewed by James Boswell (1740-1795). Boswell was disconcerted by Hume’s refusal to believe in the afterlife, and by his cheerfulness in the face of death (Miller, 1995):

I asked him if the thought of annihilation never gave him any uneasiness. He said not the least; no more than the thought that he had not been, as Lucretius observes. (Boswell, 1776).

Fear of Death

Despite the cheerfulness with which Epicurus and Hume faced death, Epicurean logic fails to convince most human beings not to fear death. Since death before maturity prevents us from reproducing, evolution must clearly have given preference to those whose fear of death made them avoid potentially fatal situations.

Epicurus promoted pleasure as the goal of life, but had difficulty handling its relation to time. Common sense definitely presumes that pleasure is greater when it lasts longer. A death that shortens a potentially pleasurable life should therefore be feared. Epicurus proposed that ataraxia is the same regardless of the duration, but his argument is unconvincing:

Epicurus holds that pleasure is the supreme good, and yet claims that there is no greater pleasure to be had in an infinite period than in a brief and limited one. Now one who regards good as entirely a matter of virtue is entitled to say that one has a completely happy life when completely virtuous. Here it is denied that time adds anything to the supreme good. But if one believes that the happy life is constituted by pleasure, then one cannot consistently maintain that pleasure does not increase with duration, or else the same will apply to pain. Or are we to say that the longer one is in pain the more miserable one is, but deny that duration has any bearing on the desirability of pleasure. (Cicero, 45 BCE, II: 88)

Nagel (1990) makes a similar point:

Observed from without, human beings obviously have a natural lifespan and cannot live much longer than a hundred years. A man’s sense of his own experience, on the other hand, does not embody this idea of a natural limit. His existence defines for him an essentially open-ended possible future, containing the usual mixture of goods and evils that he has found so tolerable in the past. Having been gratuitously introduced to the world by a collection of natural, historical, and social accidents, he finds himself the subject of a life, with an indeterminate and not essentially limited future. Viewed in this way, death, no matter how inevitable, is an abrupt cancellation of indefinitely extensive possible goods. Normality seems to have nothing to do with it, for the fact that we will all inevitably die in a few score years cannot by itself imply that it would not be good to live longer.

Most people feel that death comes before their lives have been properly completed. Some things have not yet been experienced, others have not yet been atoned for; their achievement is not enough, their legacy not sufficient. As Cicero (44 BCE) remarked “No one is so old that he does not expect to live a year longer.”

The Makropulos Case

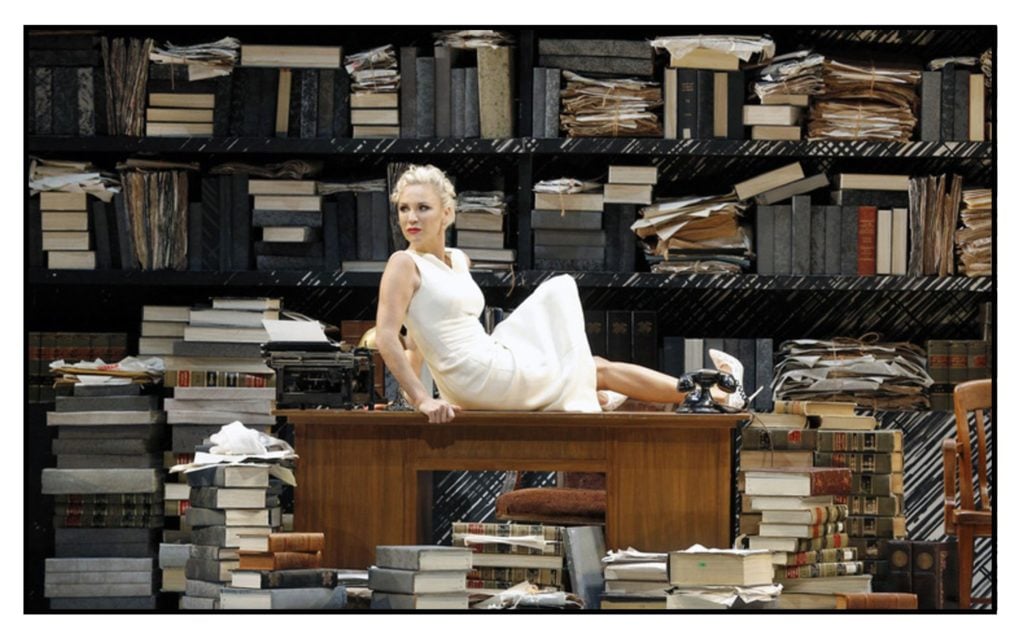

How much longer should one then wish to live? Forever may be as frightening as tomorrow. This idea was considered in an important paper by Bernard Williams (1973) that took as its point of origin a play by Karel Capek that premiered in Prague in 1922 – The Makropulos Case. Leos Janacek’s operatic version of the play was produced in Brno in 1925.

In the play Emilia Marty, a beautiful and successful opera singer, turns out to be Elina Makropulos, a young Greek woman who was given an elixir of longevity by her physician-father in 1601. Having lived over 300 years without aging she has returned to Prague to find the elixir’s formula so that she can further prolong her youth. The following photograph from the San Francisco Opera (2016) shows Nadja Michael in the role of Emilia in the first act of the opera (which takes place in a law office):

In the end Emilia decides that she does not want to live longer. She explains to the others:

Oh, life should not last so long!

If you only realized how easy life is for you!

You are so close to everything!

For you, everything makes sense!

For you, everything has value!

– for the trivial chance reason

that you are going to die soon.

… It’s all in vain

whether you sing or keep silent –

no pleasure in being good

no pleasure in being bad.

No pleasure on earth,

No pleasure in heaven.

And one comes to learn

that the soul has died inside one.

(Janacek version)

Williams (1973) agrees with Emilia. After a while immortality will become tedious. Human desires are designed for shorter periods. Evolution has made us long to live longer. Yet the usual span of human life gives us about the right amount of time to experience what we can, and to accomplish what we should.

Aubade

Another aspect of death not considered in Epicurean philosophy is that it is the end of the “person.” Each individual spends a lifetime developing a collection of experiences and achievements, out of which are derived a set of values and an accumulated knowledge. Warren (2004, chapter 4) considers these as the personal “narrative.” At death the story ends. The person vanishes. Some traces will be preserved in the memories of others but these are but faint copies of the original.

This is the reason why Lucretius’ analogy of the mirror does not work. We are not concerned with the time before we were born because we did not exist then. However, this is not the mirror image of the time after our death when we again do not exist. Because in the meantime we have existed. Time only goes one way.

Personal annihilation is perhaps the most frightening part of death. On December 23, 1977, Philip Larkin published a poem about death in the Times Literary Supplement. (The full text is available at this link). In a letter to a friend he called it “a real infusion of Christmas cheer” (Larkin, Burnett, 2012, p 495). Fletcher (2007) provides some discussion of the poem and its relation to one of John Betjeman’s. An aubade is typically the dawn song of a lover as he leaves his mistress. Larkin’s poem is a death song about leaving his life. He is intensely afraid:

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse

—The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused—nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

He laments the inability of religious faith or philosophical reason to provide any comfort:

Religion used to try,

That vast moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear—no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anaesthetic from which none come round.

Larkin provides us with no resolution of this fear. In the final lines of the poem he watches as the dawn breaks and people get ready for work. Phones will ring and letters will be delivered. Communication is perhaps our only comfort. The following is Larkin’s recitation of the poem.

Endings

So we come to the end of this essay on endings. Though death is not desired, it is inevitable. Epicurus was right about there being nothing after death, but death itself is not nothing. It marks the transition of a life from the individual consciousness to the memory of others. Henry James noted in 1916 when his final stroke began, “So here it is, the distinguished thing” (Edel, 1968, Callahan, 2005).

References

Baltzly, D. (2019). Stoicism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Berryman, S. (2016). Democritus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Boswell, J. (1776, reprinted 1970). An account of my last interview with David Hume. In Weis C. M. and Pottle F. A. (Eds) Boswell in Extremes. 1776-1778. New York: McGraw Hill. (pp 11-15). Also available at PhilosophyTalk website.

Callahan, D. (2005). Death: ‘The Distinguished Thing,’ Hastings Center Report, 35, S5-S8.

Čapek, K., (translated and introduced by Majer, P., & Porter, C., 1999). Four plays. London: Methuen Drama.

Cicero, M. T. (45 BCE, translated by Woolf, R., and edited by Annas, J., 2001). On Moral Ends. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Available at Archive.org

Cicero, M. T. (44 BCE, translated by A. P. Peabody, 1884). Cicero de Senectute (on old age). Little Brown, Boston. Available at Archive.org

Diogenes Laertius (3rd Century CE, translated by Yonge, C. D., 1853). The lives and opinions of eminent philosophers. London: Henry G. Bohn. Available at Archive.org

Durant, W. (1939). The story of civilization: Part II: The life of Greece. New York: Simon and Schuster. Available at Archive.org

Edel, L. (1968). The deathbed notes of Henry James. The Atlantic Monthly, (June 1968)

Fletcher, C. (2007). John Betjeman’s ‘Before the Anaesthetic, orA Real Fright’: A Source for Philip Larkin’s ‘Aubade’. Notes and Queries, 54, 179-181

Greenblatt, S. (2011). The swerve: How the world became modern. New York: W.W. Norton.

Inwood, B., & Gerson, L. P. (1997). Hellenistic philosophy: Introductory readings. 2nd Edition. Indianapolis: Hackett.

Jones, H. (1989). The Epicurean tradition. London: Routledge.

Konstan, D. (2018). Epicurus. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Larkin, P. (edited by A. Burnett, 2012). The complete poems of Philip Larkin. London: Faber and Faber.

Lesses, G. (2002). Happiness, completeness, and indifference to death in Epicurean ethical theory. Apeiron, 35 (4), 57–68.

Long, A. A. (1986). Hellenistic philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Sceptics. 2nd Edition Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lucretius, C. T. (~50BCE, translated by W. H. D. Rouse, 1924, with introduction and revisions by M. F. Smith, 1992). De rerum natura. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library). (Latin with English prose translation)

Lucretius, C. T. (translated by C. H. Sisson, 1976). De rerum natura: The poem on nature; a translation. Manchester: Carcanet New Press. (Blank verse translation)

Lucretius, C. T. (translated by A.E. Stallings, 2007). The nature of things. London: Penguin Classics. (Translation in rhyming couplets)

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (180 CE, translated by G. Long, 1862). Meditations. New York: F. M. Lupton. Available at Archive.org.

Miller, S. (1995). The death of Hume. Wilson Quarterly, 19 (3). 30-39

Mitsis, P. (2002). Happiness and death in Epicurean ethics. Apeiron, 35 (4), 41–55.

Nagel. T. (1970). Death. Nous, 4, 73-80. Reprinted in Nagel, T. (1979). Mortal Questions (pp 1-10) Cambridge UK; Cambridge University Press.

O’Keefe, T. (2010). Epicureanism. Durham, UK: Acumen.

Santayana, G. (1910). Three philosophical poets: Lucretius, Dante, and Goethe. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Sedley, D. (2018). Lucretius. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Warren, J. (2004). Facing death: Epicurus and his critics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Williams, B. (1973). The Makropoulos case: Reflections on the tedium of immortality. Reprinted in his Problems of the Self. (pp 82-100). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Wilson, C. (2015). Epicureanism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilson, C. (2008). Epicureanism at the origins of modernity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thanks!

Tony.

The physical broken down to atoms. All is good. The movement of atoms, fine.

“The movement of different types combine to form molecules of various chemical compounds. The pressure of a gas depends on the force exerted by the continual movement of its molecules.”

1) What is the pressure defined as that moves molecules, atoms? Do atoms move and how? With what impetus? Can they not sit still, in their own natural form?

“Atoms are infinite in number but of a finite number of types. Moving atoms collide with one another and join to form compounds. These compounds interact with each other to create all that exists in the world. Combining atoms is like forming words with the letters of the alphabet. From a few letters come a myriad words.” Absolutely beautiful.

2) Would there be any explanation as to how “the atoms permeate the body giving it a conscious spirit?” With what force?

Is the movement of atoms in conception/birth akin to the will to live and the movement of atoms away from the body in death, part of the will has died?

Regarding the movement of atoms, let’s forget about the Gods or God. They/He/She can be out of the picture, totally.

3) What is it in the atoms that move them? “They move into the void.” From where is all this movement generated? Is there an innate attraction, and what is it called?

4) Would there be an explanation as to why atoms of the soul would be extremely fine? If we’re defining “matter to the most indivisible particle,” why would the particles of the soul be different from other particles?

“The soul is composed of atoms just like everything else. The atoms of the soul are extremely fine, perhaps similar to the atoms of fire. They permeate the body, giving it a conscious spirit. When the body dies, the atoms of the soul dissolve back into the void like all the other atoms of the body. The soul does not persist beyond death. There is no afterlife.”

Thank you for the inspiring thoughts. Perhaps these are assumptions made over millennia or perhaps science has answered this already or perhaps the answer will be as elusive as God when we’re in the desert of life.

Many thanks for your perceptive comments. We do not know the complete views of the ancient atomists, since their writings are only available to us in fragments. De Rerum Natura is the fullest exposition we have of their views, but even it is incomplete. The following notes are therefore largely based on Lucretius. Neither modern scientists nor the ancient atomists have answers to all the questions:

Re 1) and 3): The atomists did not indicate a reason for why atoms are in motion. Modern science might postulate an original Big Bang, but this would not fit with the atomists’ view that the universe had existed forever. Democritus proposed that all atoms fall through the void at the same speed. This was likely based an idea of gravity, though there was no understanding of this until Newton. Democritus correctly observed that if all things fall at an equal velocity nothing would collide. He therefore introduced the idea of the clinamen. This would explain how compounds could form from atoms bumping into other. The wonderful analogy of letters and words comes from Lucretius (I:196-197). Lucretius also suggested that the clinamen might explain free will.

Re 2) and 4): The ancient atomists suggested that size could determine the type of atom. If so, there would be a limit to the number of types of atoms, since no type of atom was large enough to be visible. The soul could then be composed of a particularly “fine” (in both size and value) atom. How the soul permeated the body was not explained. Lucretius proposed that, although the soul/spirit/mind was diffused throughout the body, its center was in the chest rather than in the brain (III: 140), because our first response to fear or joy is a throbbing of the heart. Modern science has not yet provided an explanation of the soul or mind. Most evidence indicates that it is a particular pattern of activity in the neurons of the brain. If so, it is a process rather than a thing. When the body and the brain can no longer sustain this neuronal activity, the soul ceases.

Thank you Dr. Picton. Your in depth educative spirit and knowledge is most welcome, from past to present. Best wishes.

Marcus Cicero, the author and observer of his time.

“As Cicero (44 BCE) remarked “No one is so old that he does not expect to live a year longer.”

This is an absolute thought towards life and a juxtaposition to the thought of death.

Living each day at a time, perceiving what we can, imagining from those perceptions, creating from perception to reality, is life. But what is death if just a perception,from where we stand in life.

What is imagining without a future glance? Imagining cannot exist without the future and death cannot exist without imagining.

Dante Alighieri 1200’s said it best in his Divina Comedia, Paradiso: ” God said with a smile

Which lighted my soul’s new sky,

“The real world is only where thou and I are;

The earth is but space, and but sun-time each star,

To such as are thou and I.”

More to imagine! Thank you!