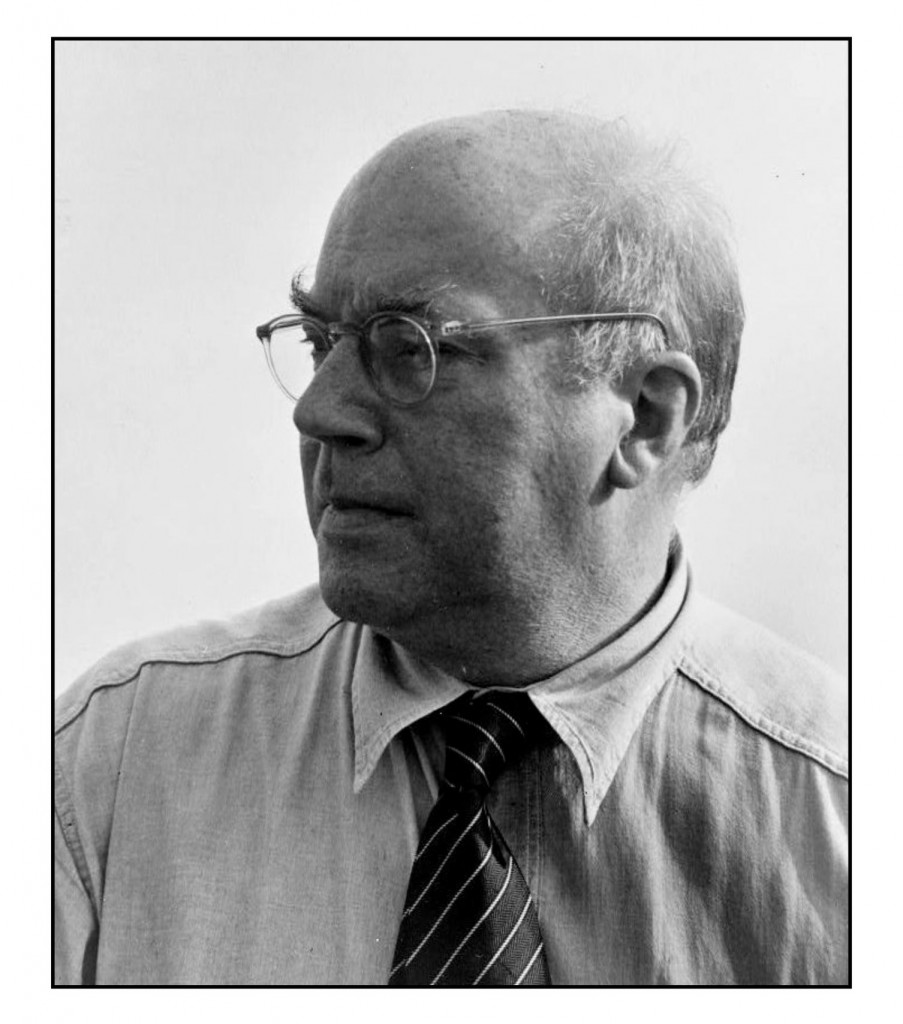

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) was the greatest of the Soviet composers. Unlike Prokofiev, who spent many years abroad, Shostakovich lived all of his adult life in the Soviet Union (1922-1991). His relations with the state were difficult. Artists do not work easily in a dictatorship.

Shostakovich talked very little about his music. His work evokes powerful emotions, but what Shostakovich means often remains unclear. Although much of his music appeared to glorify Soviet Communism, recent writers such as Volkov (1979) and MacDonald (1990) have suggested that many of his works carried subversive meanings. His life, like his music, has had many interpretations.

This posting considers some of the issues of interpretation. In a society wherein one is afraid to say what one thinks or feels, history becomes uncertain. And music is often ambiguous.