Death is inevitable. What it entails is largely unknown. Some believe that it permanently ends an individual’s existence; others that it simply provides a transition to another form of life. Most people fear it, but some consider it with equanimity. Among the latter are the followers of Epicurus, who claimed

Death is nothing to us. For what has been dissolved has no sense-experience, and what has no sense-experience is nothing to us.

(Epicurus, reported by Diogenes Laertius, translated by Inwood and Gerson, 1997, p 32; another translation is by Yonge, 1983, p. 474).

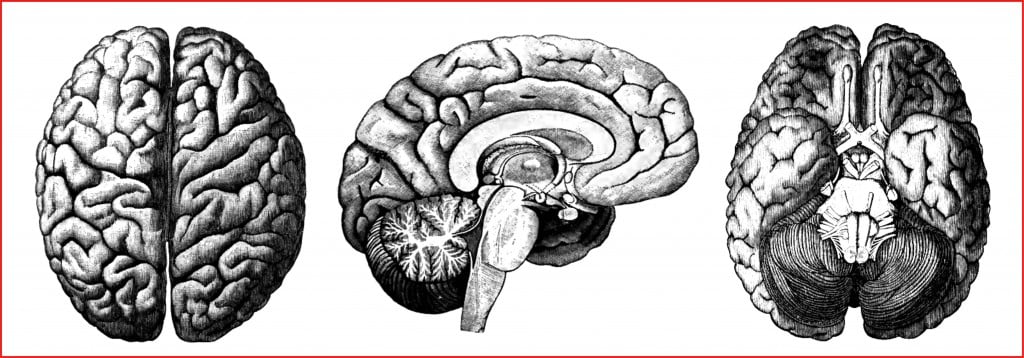

Epicurus proposed that human beings are made of complex compounds of atoms. At death these compounds dissolve, releasing the atoms to form other things. The body decays and the soul evaporates. Once we are dead, we are no more. We cannot feel what it is like to be dead. And the dead certainly cannot experience pain. Death should therefore not be feared.

Epicureanism was popular during the Roman period. A common Latin epitaph summarized the life of the Epicurean as a brief interlude between the nothingness preceding birth and the nothingness following death:

Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo

(I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care).