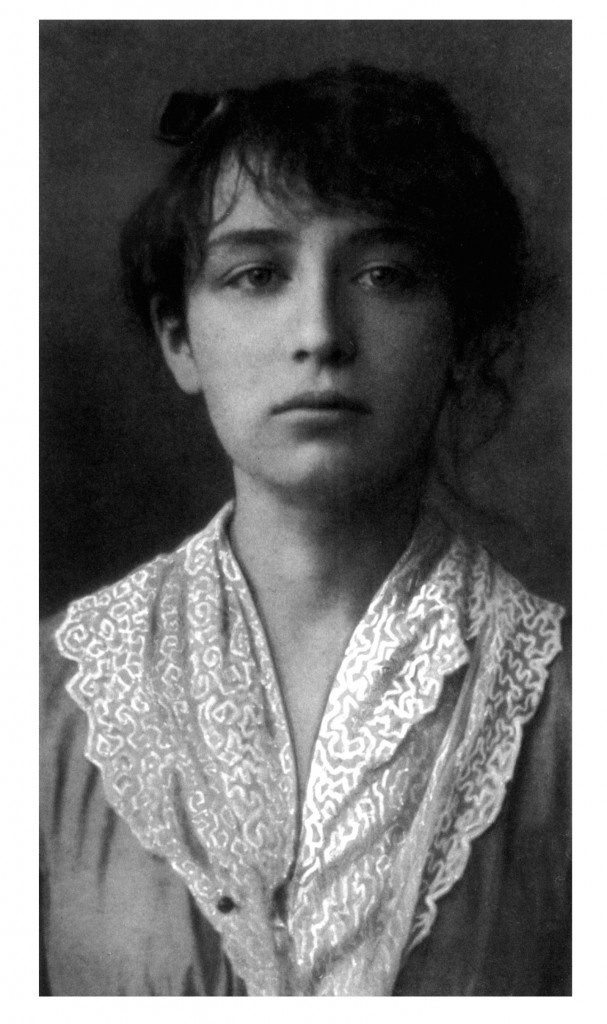

The photograph is striking. A young woman stares defiantly at the camera. One feels her passion and her sensuality. Her unkempt hair is tied back from her eyes. She is in working clothes but for the camera she has wrapped a scarf around her neck and fixed it with a pin. The photographer went by the name of César, but nothing else is known about him. The photograph was taken in 1883 or 1884. The Rodin Museum in Paris has an albumen print. The photograph was published in 1913 in the Parisian journal L’Art Décoratif (Claudel, 1913b).

The subject was Camille Claudel (1864-1943). Her younger brother remembered her:

this superb young woman, in the full brilliance of her beauty and genius … a splendid forehead surmounting magnificent eyes of that rare deep blue so rarely seen except in novels, a nose that reflected her heritage in Champagne, a prominent mouth more proud than sensual, a mighty tuft of chestnut hair, a true chestnut that the English call auburn, falling to her hips. An impressive air of courage, frankness, superiority, gaiety. (Paul Claudel, introduction to the 1951 exhibit of Camille’s sculpture, quoted in Claudel, 2008, p. 359).

At the time of the photograph, Camille was twenty. For two years, she had been learning to sculpt, sharing a studio with the English student Jessie Lipscombe, and studying with the sculptor Alfred Boucher, one of the few art teachers in Paris willing to tutor women. When Boucher left Paris for a year in Florence in 1882, he recommended his student to Auguste Rodin (1840-1917). Camille Claudel became Rodin’s student, his model, his lover, his muse and his colleague.

Read more